System and Political-Economic Transformation in China

全文

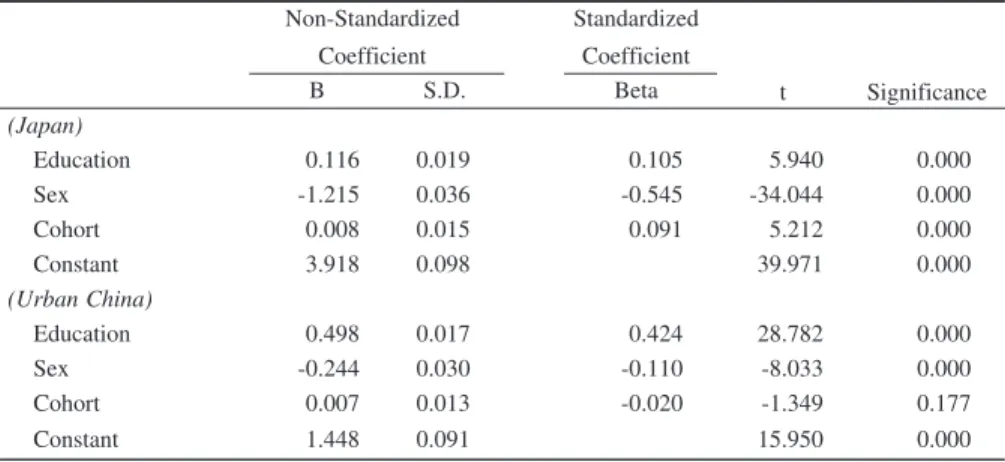

図

関連したドキュメント

A monotone iteration scheme for traveling waves based on ordered upper and lower solutions is derived for a class of nonlocal dispersal system with delay.. Such system can be used

In this note the concept of lower and upper solutions combined with the nonlinear alternative of Leray-Schauder type is used to investigate the existence of solutions for first

The nonlinear impulsive boundary value problem (IBVP) of the second order with nonlinear boundary conditions has been studied by many authors by the lower and upper functions

Erd˝ os, Some problems and results on combinatorial number theory, Graph theory and its applications, Ann.. New

Adjustable soft--start: Every time the controller starts to operate (power on), the switching frequency is pushed to the programmed maximum value and slowly moves down toward

NCx57085 is a high current single channel IGBT gate driver with 2.5 kVrms internal galvanic isolation designed for high system efficiency and reliability in high power

To transmit the large capacity and high speed signal in the devices without distortion, it is very important to apply the composed material with low loss and frequency

• If the negative pulse characteristic (negative voltage level & pulse width) is above the curves the driver runs in safe operating area. • If the negative pulse