Interlanguage Analysis of Connectives in Japanese EFL learners

73

0

0

全文

(2) Interlanguage Analysis of Connectives in. Japanese EFL Learners. A Thesis. Presen七ed 七〇. The Faculty of 七he Gradua七e Course at. Hyogo Universi七y of Teacher Educa七ion. In Partial Fulfillment. of七he Requiremen七s for七he Degree Mas七er of Educa七ion. by. Yoshida Kunio (M87241F). December 1988.

(3) CONTENTS. PAGE LIST OF TABLES. iv. LIST OF FIGURES. . iv. PREFACE. . v. Chapter l Background to 七he S七udy. . . . . . . 1. 1.1 1n七erユanguage Analysis .. . . . 1. 1.2 Definition of Connec七ives .. . . . 5. 1.3 Functions of Connectives in Discourse .. . . . .9. 1.4 Acquisition of Connec七ives.. . . . . . .14. Chap七er 2 Design of This S七udy . . . . . . . .. . . .19. 2.1 Hypo七heses . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . 19. 2.2 Subjects . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . .21. 2.3 Forma七s for Testing and Procedures . . . .. . . .22. 2.4 Tes七ing Procedures . . . . .. 26. 2.5 Measuremen七 and Evalua七ion . . .. 27.

(4) Chapter 3 Resul七s and Discussions. . . . 。 . . . . . 28. 3.1 Hypo七hesis 1 (There are quali七ative differences by leraners’ age in acquisition of con− nec七ives). . . . . . . . . . .28. 3.2 Hypo七hesis 2 (AIZUCHI:Echoic−Responsing expresses aspecial charac七eristic of Japanese EFL learners) . . . . . . . . . . 37. 3.3 Hypothesis 3 (Japanese learners can be expected七〇 have interference of LI in mas七ering the meaning and use of English connec一 七ives) . . . 。 . . . . . . . .4ユ. Chapter 4 Discussions on Some Findings. . . . . . . . .47 4.1 Double Func七ions of Connec七ives. . . . . . . . 47. Chapter 5 Conclusion. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52 APPENDIX 1’”’III . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56. Bibliography . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .59 Abs七rac七.

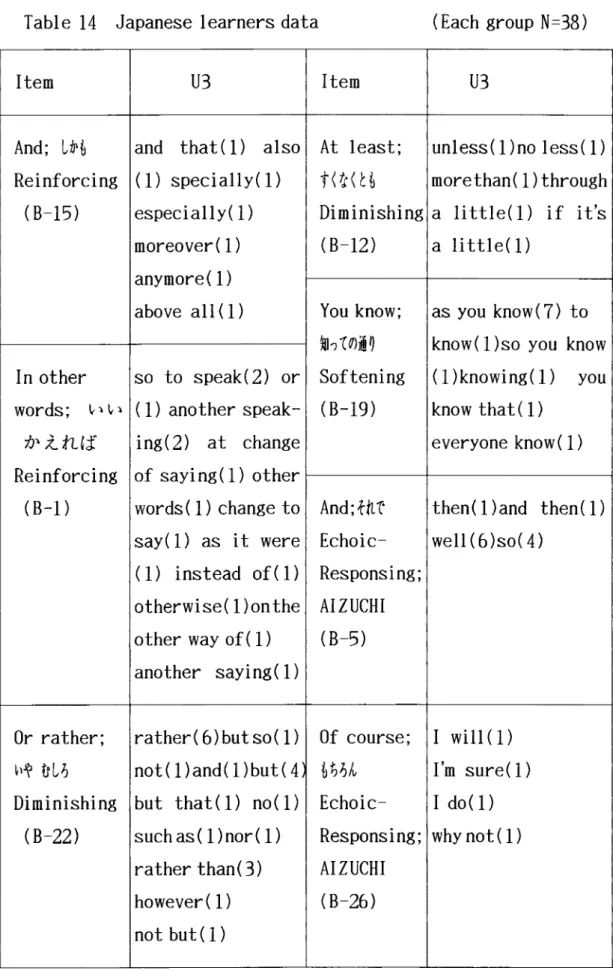

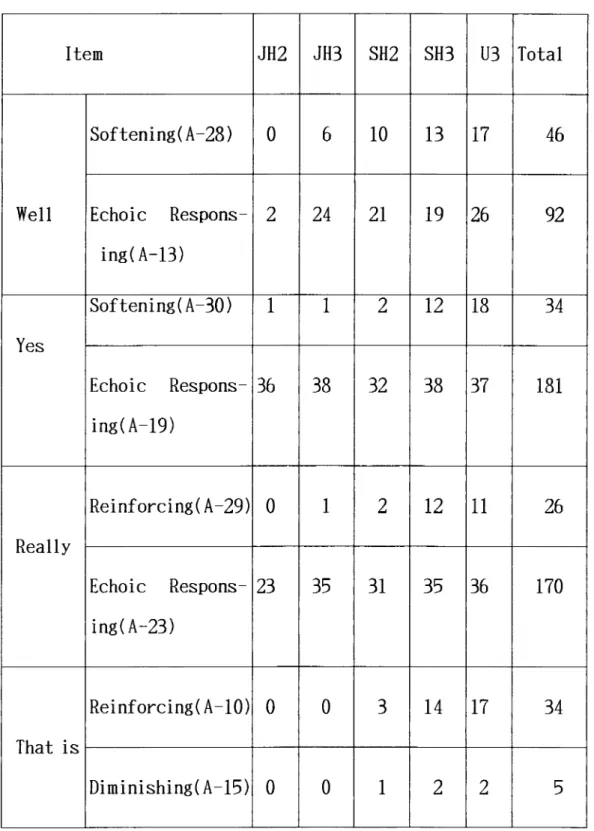

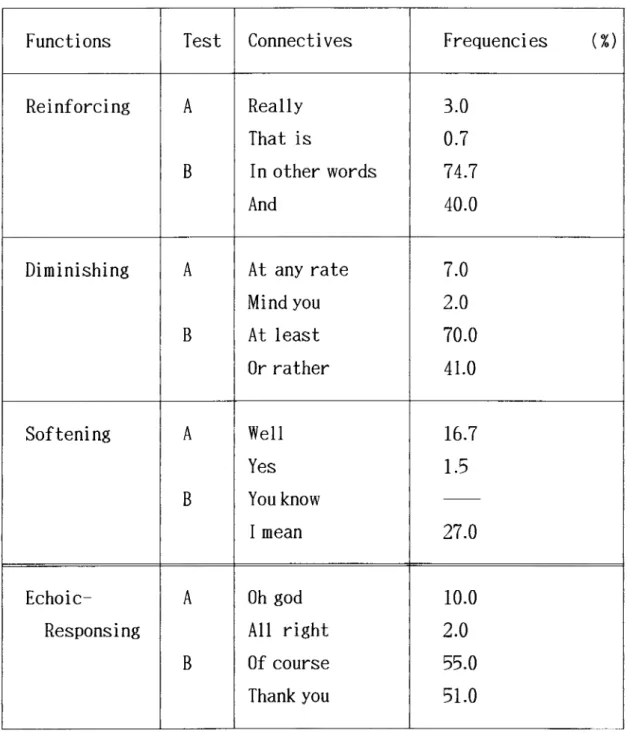

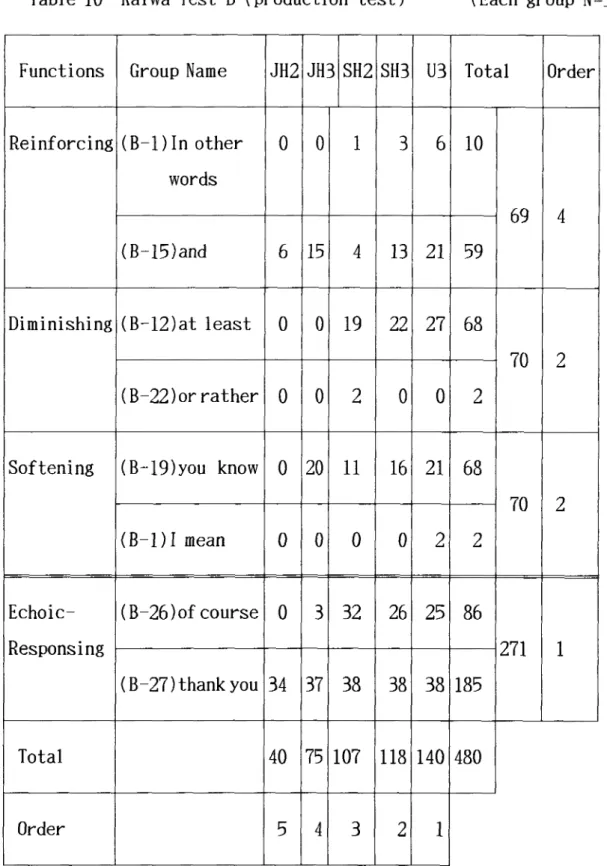

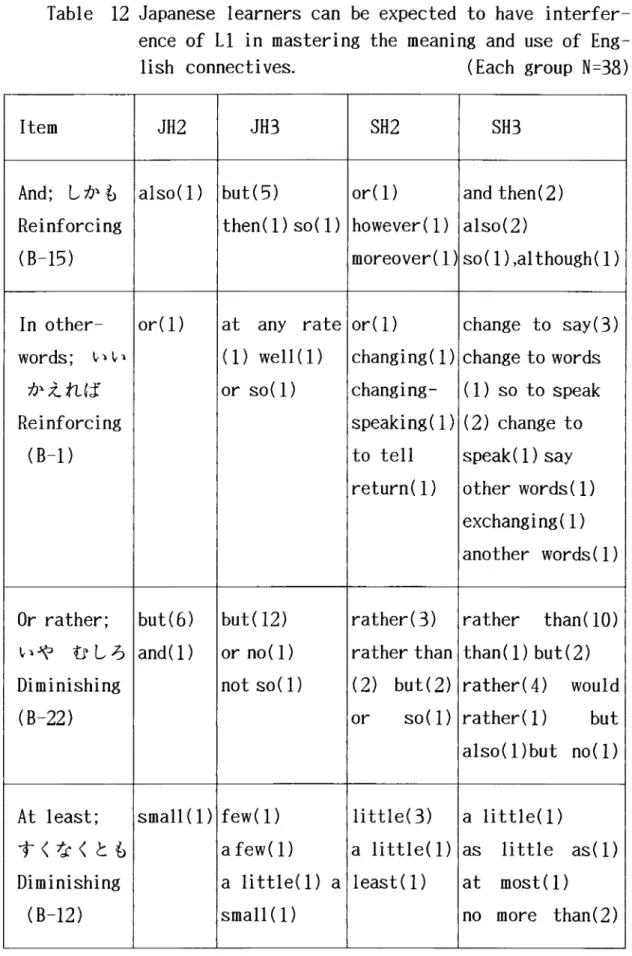

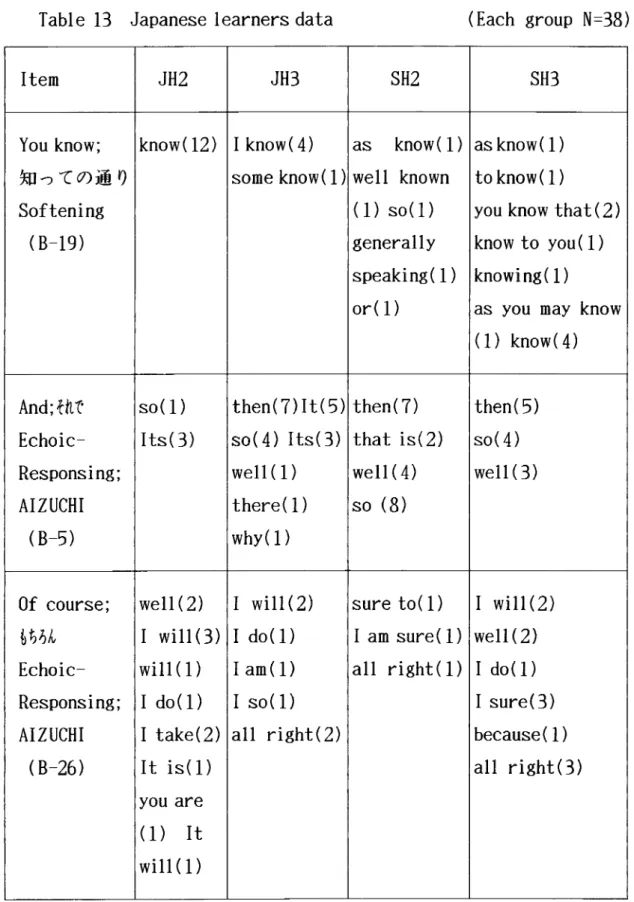

(5) LIST OF TABLES 口L−⊥. TABL. PAGE. LEXICAL ITEMS FUNCTIONING AS CONJUNCTS AND DISJUNCTS IN AN ADULT CORPUS AND FREQUENCIES OF OCCURANCES . . . 16. CORPUS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16. A FREQUENCY COMPARISON OF NSSE AND JSSE. 7 8901 45rO 32 4 5 11占−1ゐ ーーム . ∩∠ 2り . A COMPARISON OF CONJUNCTS OCCURRING MORE THAN ONCE IN THE CHILD CORPUS OF THE PRESENT STUDY AND THE ADULT. ON CONNECTIVES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17. LEARNERS GROUP . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21. GENERAL SERVICE LIST OF ENGLISH WORDS . . . . . . . 25. SUMMARY OF DATA ON KAIWA TEST A, KAIWA TEST B AND EI GORYOKU TEST FOR JAPANESE EFL LEARNERS . . . . . . 28. ANNOVA FOR QUALITATIVE DIFFERENCES BY LEARNERS’ AGE . . 29. MULTIPLE COMPARISON . . . . . . . . . . . . 29 KAI WA TEST A . . . . , . . . . . . . . . . 31. KAIWA TEST B . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32. AIZUCHI(ECHOIC−RESPONSING) EXPRESSES A SPECIAL CHARACTER− ISTIC OF JAPANESE EFL LEARNERS . . . . . . . . 37. JAPANESE LEARNERS CAN BE EXPECTED TO HAVE INTERFERENCE OF LI IN MASTERING THE MEANING AND USE OF ENGLISH CONNECTIVES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .42. 一1占19点−⊥. AS ABOVE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .43 AS ABOVE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .44. DOUBLE FUNCTIONS OF CONNECTIVES . . . , . . . . 50. LIST OF FIGURES. 1 RELATION OF AIZUCHI AND THE THREE MAIN FUNCTIONS OF CONNECTIVES BY CRYSTAL AND DAVY (1975). . . . . . . 13. 2 MULTIPLE COMPARISON BY TUKEY’S METHOD. . . . . . . 30 3 QUALITICAL DIFFERENCES BY LEARNERS’ AGE . . . . . . 33. 4 AIZUCHI (ECHOIC−RESPONSING) EXPRESSES A SPECIAL CHARAC− TERISTIC OF JAPANESE EFL LEARNERS.. . . . . . . 38 5 AS ABOVE. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .40.

(6) PREFACE. In recen七years,七here has been a growing research in七eres七. in the interlanguage analysis of Japanese EFL learners’ errors while. learning a second language. The underlying objec七ive of most of these analyses has been 七〇 reveal the systema七ici七y of Japanese learners’ errors in an effort 七〇 unders七and 七he process of second. language learning. The purpose of 七his study is 七〇 explain 七he function of. connec七ives and how connec七ives are acquired by in七erlanguage analy−. sis of Japanese EFL learners in discourse, and 七〇give sugges七ions for Japanese English 七eaching Planning. I would like 七〇 focus on. the following 七hree poin七s: 1. There are quali七ative differences. by learners’ age in the acquisition of connectives. 2. AIZUCHI (Echoic−Responsing) expresses a special charac七eristic of Japanese EFL learners. 3. Japanese learners can be expected 七〇 have in七er−. ference of LI in mas七ering 七he meaning and use of English connec一 七ives. The plan of 七his 七hesis is as follows: In chap七er 1; Background to 七he S七udy, I jus七ify 七he in七en七ion of 七he study dis−. cussing four poin七s:(i) Why do we need 七〇 s七udy in七erlanguage ? (ii) What is 七he defini七ion of connectives ? (iii) What are 七he. func七ions of connec七ives in discourse ? (iv) How do our Japanese learners aCqUire COnnec七iVeS ? In chap七er 2;Design of This S七udy, I explain how 七he re−. search investiga七ion was conduc七ed, providing hypo七heses, formats for七he 七es七ing, procedures and me七hods of measuremen七and evalu− a七ion..

(7) 弓−. ●1. In Chapter 3; Resul七s and Discussions, I make a general. survey of the results and attempt七〇analyze七he da七a from several viewpoin七s so as to七es七 七he hypo七heses. In Chapter 4;Discussions on Some Findings, I pick ou七some. in七eres七ing issues in the da七a and discuss七hem. In Chapter 5;Conclusion, I summarize七he chief points of. controversy and give final remarks. In completing this work, I would like七〇express very deep. gratitude七〇all the faculty members at Hyogo University of Teacher Educa七ion, especially to Professor Shoroku Aoki, my seminar super− visor, for the devo七ed guidance he offered at every s七age of 七he. preparation of this thesis, to Professor Ichiro Tange for providing. me many books,七〇Professor Tsunesi Miura for his workable advice, 七〇 Associate Professor Toshihiko Yamaoka for his helpful sugges− tions, to Associa七e Professor Hideyuki Takashima for providing me some data and generous suggestions and to Mr. A. J. Chick for his. valuable guidance. Furthermore, 七he in七erac七ive discussions with. fellow s七udents in his seminar have always been enlightening. Especially, I am sincerely 七hankfu1 七〇 Dr. H. Mizuno at. Kanagawa University for his sugges七ions on the subjec七,七〇 Dr. S. Tanaka of Ibaraki Universi七y for providing me wi七h七es七ing da七a and. to Professor Toshiko Waida of Osaka Women’s Universi七y for valuable comments. I am indebted 七〇七he teachers of 七he English Department. at Hyogo Universi七y of Teacher Educa七ion Junior High School in Hyogo, Otemon Gakuin Senior High School and O七emon Gakuin Universi七y. in Osaka and the s七udents there for their generous coopera七ion and assis七ance in the present study.. December 1988 Yoshida Kunio.

(8) Chapter 1. Background 七〇 七he Study. 1.1 lnterlanguage Analysis In七erlanguage (IL) refers to 七he separa七eness of a second. language learner’s system, a system tha七 has a struc七urally. intermediate sta七es between 七he native and targe七 1anguage.1 According to Long and Sato (1984) interlanguage research has beeR limi七ed by a 七endency to focus on 七he following four poin七s that: (1) product rather than process, (2) form rather than functien, (3). single ra七her than multiple levels of linguistic analysis,(4) IL in isola七ion rather七han in i七s linguis七ic and conversational con七ex七。2. Mos七second language acquisi七ion(SLA)research in七he 1960s was done in七he approach of (1). Tha七was conduc七ed wi七hin七he frame− work of con七rastive analysis(CA).The shift from a focus on product to a focus on process in IL developmen七 has resulted in the replace−. ment of what might be called a‘form only’analysis of IL da七a to a. ‘form−to−function’ mode of analysis. While 七he former aims to measure increasing targe七一like produc七ion of particular forms, the latter a七七emp七s a comprehensive analysis of七he func七ional dis七ribu一 七ion of a particular form in a learner’s IL.3 Error analysis (EA>. i H. Douglas Brown,. Principles of Language Learning and. N. J.: Pren七ice−Hall, 1987), p.169. Teaching (Englewood Cliffs,. Criper and A. P. R. Howatt, eds. Z AIan Davies C. In七erlanguage S七udies: An Interac七ionis七 “Methodological Issues in Interlanguage (Edinburgh: Edinburgh Universi七y. Perspective,” in. Press, 1984), P.253. 3 lbid, (1984), pp.265−266..

(9) 2. was a main current of the study of SLA from the last par七〇f l960s to the first period of 1970s. Corder (1967)proposed 七〇 analyze the learners’interlanguage of a 七arget language. Then Nemser (1971) and. Selinker(1972)supPorted his idea and七his led to a new era of the interlanguage study. However there were a lo七〇f weaknesses in七his approach. Schachter and Celce−Murcia (1977) identified some weak一. nesses. which are as follows that: (1) Due to its focus on errors, error analysis. produced only partial accounts of ILs, saying li七tle about wha七 the learner was doing was correct. (2) Analys七s often classified errors. subjectively, sometimes underestima七ing 七he Ll as a source of error because of lack of familiar−. i七ywith七he range of na七ive language represen七ed in 七heir sample. (3) By focusing on wha七 the. learner did (wrongly), error analysis ignored avoidance (Kleinmann 1977 ; Schachter 1974).i. The various apProaches to overcome 七hese weaknesses were . (1976) and Pica (1983). They combined the following done by Hakuta. strengthes in. each of CA and EA. CA: (1) It was recognized that the difficulty. predicted by CA might be realized as avoidance instead of error. (2) It was recognized tha七. error was a multi−fac七〇r phenomenon and that in七erference, as one of 七he fac七〇rs, interacted in complex ways wi七h other factors.. i Alan. pp.256−257.. Davies, C. Criper and A. P. R. Howat七, eds. (1984),.

(10) 3. EA:(1)EA helped七〇demonstrate that many of七he errors七hat the second language learners made were not 七raceable to the firs七 language (Ll). (2) 1七. also helped七〇 identify some of七he process that were responsible for interlanguage development.’ On the o七her hand, a second line of research on IL, begun a. li七tle later七han EA s七udies, but which came七emporarily七〇domina七e. North American SLA research in七he 1970s, was performance analysis (PA), initially represented by so−called ‘morpheme s七udies’. The morpheme studies reflec七ed a reaction by SLA researchers to a devel− opment in research on firs七 1anguage acquisi七ion.2 PA looked at both. 七he second language performance and erroneous performance. However the following weaknesses have been pointed to PA such as: there is not a sufficien七 七heoretical base for assuming 七ha七 七he accuracy. with which learners use morphemes corresponds to the order in which. they are acquired.3 Since the mid−seventies both CA and EA have been partly. absorbed and superseded by the development of interlanguage analysis (IA). A main issue in IL studies has been七he linguistic and and. 1 Rod Ellis, Understanding Second Language Acquisi七ion 〈Oxford:. exford University Press, 1986), p.33. 2 Alan Davies, C. Criper and A. P. R. Howatt, eds.. (1984),. p.258.. 3 Rod Ellis, (1986), p.69..

(11) 4. conversational context of IL performance since 七he mid−1970’s. Because the da七a of the linguis七ic and conversa七ional con七ext of IL. performance reflec七 七he learners’compe七ence mos七. For instance Krashen(1976), Ha七ch(1978), Larsen−Freeman(1980)and Zob1(1983) analyzed 七he con七ex七 〇f IL performance.. Almost recen七s七udies in IA have been done in七he linguis一 七ic and conversational con七ex七. Therefore by 七he use of i七, 1 七hink. tha七 we may be able 七〇 elici七 七he in七erlanguage behaviors of 七he. second language learners. In七his paper, I would like to analyze our. Japanese EFL learners’ in七erlanguage in conversa七ional con七ext in discourse..

(12) 5. 1.2 Definition of connectives Richards, and Plat七 e七 a1.(1985)give the following defini−. tion of connectives: (1) a word which join words,phrase, or, clause 七〇ge七her,such as bu七,and,when. Units larger. than single words which function as conjunc七ions are some七imes known as conjunc七ives, for example so 七ha七, as long as, as if. Adverbs which are. used七〇 in七roduce or connec七 clauses are some一 七imes known as conjunc七ive adverbs,for example however,never七heless. (2) 七he process by which. such joining take place. There are two types of conjunc七ion. (a) Co−ordina七ion,七hrough 七he use. of co−ordina七ing conjunc七ions (also known as co−ordinators) such as and, or, but. These join. linguis七ic uni七s which are equivalent or of the. same rank.(b) Subordination,七hrough 七he use. of subordinating conjunc七ions (also known as subordina七〇rs) such as because, when, unless, 七ha七. These join an INDEPENDENT CLAUSE and a DEPENDENT CLAUSE.i. Shimizu(1965)claims七ha七connec七ives are words which join words, phrase, or clauses 七〇gether, such as, rela七ive pronoun, rela七ive. adverb and conjunction.2 From 七he above, Richard e七a1.(1985)and Shimizu (1965)bo七h. indica七e 七ha七 connectives are words which join words, phrases or. l Jack Richards, John Pla七七 and Heidi Weber, Longman. Dictionary of ApPlied Linguis七ics (London:Longman Group Limited, 1985),. p.58.. 2 Shimizu Mamoru, BAIFUKAN’S DICTIONARY OF ENGLISH GRAMMAR (Tokyo: Baifukan, 1965),. p.159..

(13) 6. clauses 七〇ge七her. Fernald (1904>sugges七s 七ha七: There are certain words that express the great essen七ials of human 七hough七, as objects, quali七ies, or ac七ions; these are nouns,adjec一. 七ives , and verbs. Such words must always make up 七he subs七ance of language. Yet these are. dependent for their full value and u七ili七y upon another class of words, the 七hought−connec七ives, 七hat simply indica七e relation; 七hese are pre− posi七ions, conjunc七ions, rela七ive pronouns and adverbs. ’. He claims七ha七‘‘wi七hou七such七hough七一connectives all speech would be made up of brief, isola七ed, and fragmentary s七a七emen七s. The movement. of 七hough七 would be constan七ly and abruptly broken.”2 Ba11 (1986). comments abou七1ink words as follows: _by 七he use of link words(connec七〇rs), which. act markers七〇indicate七he rela七ionships between. ideas. These link words are as important in informal conversation as七hey are in七he con七rol of wri七ten English...Amonges七 the considerable number of link words indispensable七〇七he logical composition of ordinary conversa七ion, and wi七hout which it would fall apar七, is a small group, of. amazing populari七y,七hat seems to serve no pur− pose excep七, perhaps, to comfor七七he speaker and preserve his self−confidence.3. i James C. Fernald,. Funk &. Wagnalls Company,. Connec七ives of English Speech(London= 1904), vii.. 2 lbid. vii. 3 W. J. Ball,. Dic七ionary of Link words in English Discourse. (Dublin: Macmillan Publishers Ltd. 1986), V..

(14) 7. He says that ‘‘七hey are readily identifiable: you know, you see, I mean, sort of, well, anyway, ac七ually, of course, however, know. what I mean?They add no七hing七〇七he meaning of wha七we say. Their use, one suspec七s, has become an addic七ion.”1 Quirk et al.(1972>. refer 七〇 you know, I mean, sort of, you see, and 七he like as. ‘commen七clauses.’They are somewhat loosely rela七ed to七he res七〇f. clause they are belong 七〇, and may be classed as disjunc七s or conjunc七s.2 Fur七hermore, Quirk e七 al.(1985) remark 七ha七 ‘‘conjunc七s. have 七he function of conjoining independent units rather 七han one of. con七ribu七ing ano七her facet of informa七ion to a single in七egra七ed uni七.”3 Schourup and Waida(1988)say七hat: _in using 七he word ‘connec七ives’ to describe items such as AFTER ALL, BECAUSE and WELL, we are no七 using 七he 七radi七ional grammatical label that would be a七七ached 七〇 these i七ems. The expressions. we consider here belong to various gramma七ical classes: conjunc七ions, adverbs, in七erjections, and parenthetical clauses. We use七he word‘connectives’. 七〇 refer to a func七ion which all of the items discussed here have in common:七hey are all especially impor七an七 in extended discourse.4. i W. J. Ball, (1986), V・. 2 Randolph Quirk et al. A. Grammar of Con七emporary English. 1972), p.778−780. (London:Longman Grouop Limi七ed,. 3Randolph Quirk and Sidney Greenbaum e七al. A Comprehensive. Grammar of the English Language(London: Longman Group Limited, 1985),. p.631.. ‘ Lawrence Schourup and Waida Toshiko, (Tokyo:. Kuroshio Shuppan, 1988), P.8.. ENGLISH CONNECTIVES.

(15) 8. They say that we are not using the 七raditional gramma七ical label 七ha七would be at七ached七〇七hese items and use七he word ‘connec七ives’ to refer to a func七ion. On the o七her hand, Schiffrin (1987)analyzes oh, well, and, or, so, because, now, 七hen, I mean, and y’know as. discourse markers and opera七ionally defines七he markers as sequen− tially dependent elements which bracke七 uni七s of talk.1 As I quoted above, i七 can be safely said that ‘connec七ives’. are indespensable to七he logical composi七〇n of ordinary conversa− tion. They also have七he func七ions that comfor七七he speaker and pre−. serve his self−confidence in extended discourse.. ’ Deborah Schiffrin, Discourse Markers (Cambridge: Cambridge Universi七y Press, 1987), p.31..

(16) 9. 1.3 Func七ions of Connectives in Discourse In the previous clause, I sugges七ed 七ha七 connec七ives are. indispensable to 七he logical composition of ordinary conversation,. 七〇 comfort the speaker and to preserve our self−confidence in ex七ended discourse.. Here 1 would like to consider the following three main functions of connectives by Crystal and Davy (1975) as: (a) Rein−. forcing (b>Diminishing(c)Softening in connection wi七h七he above stated. Furthermore, in addition七〇七his, I also would like to refer 七〇 AIZUCHI (Echoic−Responsing) finally.. Crys七al and Davy(1975)1nominate七he three main func七ions of. cormectives as follows:(a) ‘‘Reinforcing may take 七he form of a complete repe七i七ion of what has just been said, or a paraphrase of it, or it may add a fresh piece of information arising of it.” (e.g.. in other words, that is, really, and) In o七her words proposes another way of saying what has just been said and quite of七en it is. used as a summary. Tha七 is belongs to 七he concept apPosi七ion:the addition of one word or group of words to ano七her as explanation.. Really can seek reassurance or confirmation, and can empha− size a fact, or add a degree ef conviction.2 And may also. 1 David Crys七al and Derek Davy, Advanced Conversa七ional 1975), pp.89−90. Limited,. English (London: Longman Group. 2 W. J. Ball, (1986), p.64−109..

(17) 10. reinforce, it should be no七ed, whenever it is used as a separate tone−uni七 (usually wi七h a rising or a falling−rising tone)or give. ex七ra prominence. For instance, I got jam−And I didn’七forge七七he bread.1 (b) ‘‘Diminishing connec七ive re七rac七s 七he whole or par七. 〇f 七he meaning of wha七 has preceded. The diminishing phrases, by con七ras七, are generaUy in a lower pi七ch−range.” (e.9. at least, or ra七her, a七 any rate, mind you) A good example occurs in:we’re. looking forward to bonfire 一一at leas七 七he children are.2 1七 was. late las七 nigh七, or ra七her early 七his morning.3 At any rate qualifies ei七her previous asser七ion, or one七he speaker or wri七er is now making, by res七ricting a word or phrase in i七.4 Mind you is used. 七〇 express 七he speaker’s awareness.5 1n summary, diminishing connec七ives expresses 七ha七 七he speaker feels 七he need 七〇 s七ate a. different or addi七ional viewpoint from wha七 he or o七her speakers have already expressed, but he wishes 七〇 do 七his withou七 causing offence.(c) ‘‘Sof七ening connectives alters the stylis七ic force of a sen七ence, so as 七〇 express 七he a七七i七ude of 七he speaker 七〇 his. listener, or 七〇 express his assessmen七 〇f 七he conversa七ionaI. i David Crystal and Derek Davy, (1975), p.90. 2 lbid, (1975), p.90.. 3 Sato Hiroshi, A Primer of Colloquial English (Tokyo: Kenkyusha, 1951), p.225. ‘ W. J. Ball, (1986), p.24−. 5 David Crystal and Derek Davy, (1975), p.100..

(18) 11. situa七ion as formal. i (e.g. you know, we11, I mean, yes)You know. is more like a hesi七a七ion noise which warns the lis七ener七ha七 some re−planning is going on. Well usually occurs initially in any string of sof七ening Phrases. If i七 〇ccurs in second place, it is usually. preceded by a brief pause and七his usage would generally be consid− ered hesi七ant.2 The main func七ion of I mean is七〇indica七e tha七the. speaker wishes to clarify the meaning of his immediately preceding expression.3 Yes is in effec七 to summarize a convic七ion build up over previous sen七ences, ei七her on七he par七〇f七he same speaker, or some else.‘. As for AIZUCHI:AIZUCHI(Echoic−Responsing)has an impor七an七 role 七〇 go our conversa七ions on smoo七hly.5 Here I would like 七〇. compare七he func七ions be七ween ‘AIZUCHI’and ‘connec七ives.’Mizutani (1981)6sugges七s七ha七‘‘AIZUCHI is given in response七〇signals from 七he speaker, and七he lis七ener may also be promp七ed to add even more. according 七〇 the in七〇nation used.”And Ball (1986)commen七s about. link words as:_七hat seems to serve no purpose excep七, perhaps,. 1 David Crys七al and Derek Davy, (1975), pp.91−92. 2 Ibid, (1975), p.102. 3 lbid, (1975), p.97.. 4 David Crys七al arld Derek Davy, (1975), p.100.. 5 Aoki Shoroku and lkeura et al. eds.Eigo Shido Hand Book3. Shido Gijutsu−Hen (Tokyo: Taishukan, 1983), p.622. 6 Mizutani Osamu, Japanese: The Spoken Language in Japanese Life (Tokyo: The Japan Times, Ltd. 1981), p.85..

(19) 12. to comfort 七he speakers and preserve his self−confidence.10n the one hand, Crys七al and Davy (1975) say that ‘‘Softening connec七ives. alters the stylistic force of a sentence, so as 七〇 express the at七itude of 七he speaker 七〇 his lis七ener, or 七〇 express his. assessmen七〇f七he conversa七ional situa七ion as formal.”2 As I men七ioned above, I guess七ha七七he functionen of AIZUCHI is related to 七ha七 〇f connec七ives such as:七he rela七ion of 七he. speaker and七he listener in Figure 1. The examples of AIZUCHI are as follows:(oh god, all righ七, of course, thank you). (oh god); A: A truck jumped into my house. B: Oh god, what a shame!3. (all righ七);A: 1’m sorry, I didn’t understand you. B: All righ七, 1’11 repea七 i七.4. (of course);Boris:Would you care to Play me some七hing? Some七hing of you own, I mean.. Julian:Of course, if you wish it.5(一The Red Shoes). i w. J.. Ball, (1986), V.. 2 David Crystal and Derek Davy, (1975), pp.91−92.. 3 Tazaki Kiyo七ada, TAZAKI’S ENGLISH CONVERSATION (Tokyo: Taishukan, 1980),. Weeks. PRACTICE. p.103.. 4 Horiuchi Ka七suaki et al. English Conversation in Six , p.40. (Tokyo: Obunsha, 1977). 5 Sa七〇 Horoshi. A. Kenkyusha,. 1951), p.95.. Primer of Colloquial English (Tokyo:.

(20) 13. (thank you);Ka七e:You droPPed your handkerchief. Smi七h:Oh,七hank:you。 I didn’t notice. l. Thus of course credi七s the lis七ener wi七h七he same factual. knowledge tha七七he speaker possesses. Consequen七1y,1七hink七hat七he func七ion of ‘AIZUCHI’ is very similar 七〇 七ha七 〇f ‘connec七ives’.. Therefore, in七his paper, I would like七〇 include AIZUCHI func七ion. in 七hese four func七ions in order to discuss 七he acquisi七ion of. connec七ives in Japanese EFL learners.. Figure l The rela七ion of AIZUCHI and七he七hree main func七ions of connectives by Crys七al and Davy (1975). Reinforcing (Speaker). AIZUCHI (Listener). Diminishing. Sof七ening. (Speaker). (Speaker). 1Takamoto S七esaburo, e七a1. A Handbook of American English Conversa七ion (Tokyo: Obunsha, 1977), P.21..

(21) 14. 1.4 Acquisi七ion of Connec七ives. Here, 1 would like to focus on the following three points:. (a)the developmental effec七with age,(b>afrequency comparison of Na七ive speakers and Japanese speakers on七he use of connec七ives,(c). 七he acquisition of connectives in Japanese learners. (a) Scott (1984)1 says 七ha七 ‘‘early ways of achieving. conRectivity may include mechanisms as basic repetition, or simply talking broadly abou七七he same topic(Bloom, Rocissano&Hood,1976> and 七hen, explicit connec七ives forms apPear.” Bloom and Lahey et al.(1980>2 document七he beginning stages of a variety of connec七ive forms(conjunc七ions, wh−pronouns, and rela七ive pronouns).And is七he. firs七and mos七frequen七 lexical items as an indica七ion of a simple. additive relation. However,七he child has expanded the connectivity reper七〇ire within a year’s time (Bloom et a1,1980). By 七he age of. five, the coordinating and subordina七ing conjunc七ions as well as the. 七emporal adverb then apPear. The mos七 frequen七 connec七ives in decreasing rank order are inferential 七hen, resul七 so , concessive. 七hough,七ransitional now, and concessive anyway. The developmen七al. effect wi七h age is strong with七he 10−and 12−years−01d children showing a three一七imes increase in the use of connec七ives over the 6. −year −01ds. Developmen七 is reflected not only in the increased. 1Cheryl M. Scot七,‘‘Adverbial Connectivity in conversations of children,” J. Child Lng. 11 (1984), p.423. 2 Ibid, p.424..

(22) 15. production of frequen七ly occurring connectives (then, so, 七hough,. now, anyway), but also in the production of a wider variety of different lexical items. Crys七al and Davy (1975)1 s七udied 七he iden七ifica七ion and. frequency of conjuncts. The resul七s are shown in Tables l and 2. In. addi七ion to a frequency comparison of七he child and adul七da七a, the. actual lexical i七ems and七he logical relations encoded can also be compared. The resulting da七a show tha七七he children are learning the same basic se七 〇f connec七ives 七ha七 〇ccur in the adult community.. Furthermore, connec七ives which are of low frequency in the child data may very well be of a low frequency in the adu1七communi七y as we11. Bu七, i七 is an in七eres七ing Poin七 七ha七 七he logical rela七ions. missing in 七he child data do no七 appear in the adult da七a.(e.g. child:一, adult: however) (b) Kaki七a and Ozasa et al.(1983)2 analyze the total dif−. ferences of七he use of the linguis七ic i七ems between Na七ive Speaker’s. Spoken English (NSSE) and Japanese Speaker’s Spoken English (JSSE) using the method of Crys七al and Davy(1975).. 1 Cheryl M. Sco七七,(1984), p.434.. 2 Kakita Naomi and Ozasa Toshiaki e七 al. BUNSEKI; Error Analysis of English (Tokyo: Taishukan, 146.. EIGO NO GOTO 1983), pp.144一.

(23) 16 Lexical i七ems func七ioning as conjuncts and disjunc七s in an adult corpus and frequency of occurrence. Table 1. (from Crystal & Davy,1975 〉’. Conjunc七s Enumerative/Addi七ive Transitional. Now(4). Apposi七ion. For example(3). Result. So(33). Inferen七ial. If−then (4),七hen(9). An七ithe七ic. Bu七七hen(1). Concessive. Anyway(7),a七any ra七e(1), at leas七(1),. Also(3), then(4). a七七he same七ime(1), however(3), though(3), ye七(4). To七al 81. Disjunc七s Generally(1), if you like(1),. Style. in a sense(1), in a way(1). A七titudinal. Actually(4), cer七ainly(2), for七unately(1), in fact(3), maybe(2), obviously(4),. of course(13), perhaps(1), probably(7), really(7), unfor七una七ely(1),. very unwisely(1). Total 50 Table 2 A comparison of conjunc七s occurring more七han once in 七he child corpus of the present study and 七he adult corpus(from Crys七al&Davy,1975). Child. Adult. Enumera七ive/addi七ive. Then. Transi七ional Apposi七ion. Now. Then Also. Now For example. Like. Say So. Result Inferential Anti七hetic. Concesive. So. Now. Then Otherwise Instead. Then Bu七 七hen. Anyhow Anyway. Anyway. A七 leas七. At least. Except Only Though. Though However Yet. i Cheryl M. Scott, (1984). p.435..

(24) 17. The resulting data is as follows: Table 3 frequency comparison of NSSE and JSSE on connec七ives (Ozasa, 1979 b: 212−3>. Frequency. Features NSSE. Reinforcing connec七ives Diminishing connec七ives. 00 4. Sof七ening connectives. e Ven. JSSE. 60 1. even. This result shows七hat JSSE use more of the sof七ening. connectives than NSSE. By the use of the softening connectives, the JSSE seem to prolong the span of speech and七his expresses a. characteris七ic of our Japanese learners’ interlanguage. (c)The acquisition of condi七ional and concessive conjunc−. tions in Japanese seems七〇be qui七e precocious. The early acquisi−. tion of conjunctions is linguistic:i 一te ‘and/and then/and so; 一tara ‘when/if,’and cer七ain other Japanese connectives are actually. verbal inflections; 一七emo ‘even 七hough/a1七hough,’ is formed by. simply adding the par七icle mo ‘also/even,’which is a very early. 1Pa七ricia M. Clancy, Acquisition of Japanese in The Cross一. 1inguistic Study of Language Acquisi七ion Volume 1:The Data ed. Dan Issac Slobin, (London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 1985), pp.439−474..

(25) 18. acquisition, to the −te form of 七he verb. And more sophis七ica七ed 七emporal connectives are acquired, including to ‘when/whenever/if,’. which expresses both sequence and conditional. Hence if we 七ranslate 七〇〇r mo in七〇English, we would. probably be faced at 七he acquisi七ional difficulty in七he mas{;ering 七he use of 七hem. Because English and Japanese connec七ives do no七 always have simple one−to−one equivalents. For example, we七ranslate Japanese word 一七〇 back in七〇 English, we find and, with, when, if,. whenever, as,七〇, and from. Another Japanese s七ructural word −mo. corresponds variously to also, both.”and, as much as, (n)either_(n)or, whe七her_or, even, prosodic emphasis, ever, if, or though. i. This comparison be七ween Japanese and English structure seems to refer七〇CA only. Celce−Murcia and Hawkins(1985)2 say七ha七 CA survives in IA as ‘1anguage 七ransfer’.2 Here, I would like 七〇analyze ‘and’mainly from a viewpoin七〇f IA.. ’ Michael Swan and Bernard Smith, Learner English (Cambridge. : Cambridge University Press, 1987), pp.220−221.. 2 Marianne Celce−Murcia, ed Beyond Basics Issues and Research in TESOL (Rowely, Mass.: Newbury House Publishers, lnc. 1985), p.60..

(26) Chap七er 2. Design of This Study. 2.1 Hypo七heses There are七hree hypo七heses七〇be七es七ed here. Hypo七hesis l There are quali七a七ive differences by learners’ age in acquisition of connec七ives.. Hypo七hesis 2 AIZUCHI (Echoic−Responsing) expresses a special charac七eristic of Japanese EFL learners.. Hypothesis 3 Japanese learners can be expected 七〇 have inter− ference of Ll in mastering the meaning and use of English connec七ives.. As for 七he acquisi七ion of a second language(L2),Dulay. (1981)claims as follows 七hat: the firs七 proposal focuses on biological fac七〇rs.. A second explanation focuses on the learner’s cognitive developmental stage. A七丁目rd explana一 七ion proposes differences in七he affec七ive fil七er. as a source of child−adult differences. The fourth proposal, and 七こ口 las七 we shall consider,. sugges七s differences in七he language environmen七 for children and adults as a source of difference for L2 acquisition.’. From this, I could Hypo七hesis I as stated above.. 1 Heidi C. Dulay, Marina K. Bur七, and S. Krashen,. Two (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982), pp.86−87.. Language.

(27) 20. As for Hypo七hesis 2,0samu and Nobuko Mizutani l suggest. as follows:‘‘AIZUCHI is used as a signal七〇show tha七七he listener is lis七ening at七entively and wan七s 七he speaker 七〇 go on. And 七his. is quite differen七from the western notion of wha七conversation should be like.”. Regarding Hypo七hesis 3, Swan and Smith(1987)say七hat: English and Japanese conjunc七ion do not always have simple one−to−one equivalents. And, for in−. stance, corresponds 七〇 at least eleven different Japanese forms, depending on whe七her they connect nouns, adjec七ives, verb or clauses. Thus Japanese. s七udents can七herefore be expec七ed七〇 have more 七rouble 七han Europeans in mas七ering 七he meaning and use of English conjunctions.2. 0n these reasoning, I formed Hypo七hesis 3.. lMizu七ani Osamu and Mizutani Nobuko,(1981), p.15. 2 Michael Swan and Bernard Smith, (1987), pp.220−221.

(28) 21. 2.2 Subjects My subjec七s were 190 Japanese EFL learners of a junior high. schoo1(Hyogo Universi七y of Teacher Education Junior High Schoo1,2nd grade:38 and 3rd grade:38)in Hyogo, a senior high school(〇七emon Gakuin Senior High School, 2nd grade: 38 and 3rd grade: 38 ) and a. university(Otemon Gakuin University ;The Facu1七y of Le七ters Eng− lish and American Language and Li七era七ure, junior: 38 ) in Osaka. Mos七〇f these Subjects(Ss )has no experience of living in. English−speaking coun七ries, and all had 七aken English lessons for more than two years. The selec七ion was made on the basis of Kaiwa. Test A ( Comprehension English Test), Kaiwa Test B ( Production English Tes七 ) and 七he Tanaka English Proficiency Test, which was. developed to measure Japanese learner’s levels of proficiency in English. 1七 consis七s of a CLOZE TEST.1 For data elici七a七ion, I. grouped七he Ss in七〇 七hree major groups and five subgroups as fol−. lows: Table 4 Learners group. Number. Year. School. Universi七y. To七a1. 8つ0 0000000 ⊃つ⊃つつつ⊃つ⊃. Senior high. ∩∠つ⊃今∠つ⊃つ⊃. Junior high. Group name JH2 JH3 SH2 SH3 U3. 190. 1 Tanaka Shigenori, ‘‘Eigoryoku Tes七: Par七 1”, P.20..

図

+3

Outline

関連したドキュメント

七圭四㍗四四七・犬 八・三 ︒ O O O 八〇七〇凸八四 九六︒︒﹇二六〇〇δ80叫〇六〇〇

一一 Z吾 垂五 七七〇 舞〇 七七〇 八OO 六八O 八六血

︵大阪讐學會雑誌第十五巻第七號︶

経済学の祖アダム ・ スミス (一七二三〜一七九〇年) の学問体系は、 人間の本質 (良心 ・ 幸福 ・ 倫理など)

〔追記〕 校正の段階で、山﨑俊恵「刑事訴訟法判例研究」

[r]

(a) a non-originating material harvested, picked, gathered or produced entirely in a non-Party which is a member country of the ASEAN shall be transported to the Party where

ニューゲイト監獄の教誨師はロンドン市参事会によって任命された︒教誨師はニューゲイト・ストリートに地租を免除された住