An Investigation for Clarifying the Difficulties in Learning English Vocabulary by Japanese Junior High School Students

全文

(2) An Investigation for Clarifying the Difficulties. in Leaming English Vocabulary by Japanese Junior High School Students. A Thesis Presented to The Faculty ofthe Graduate Course at. Hyogo University of Teacher Education. In Partial Fulfi11ment of the Requirements for the Degree of. Master of School Education. by Eriko Takeuchi (Student Number: M1O132B) December 201 1.

(3) i. Acknowledgements. This thesis could not have been completed without the heartwarming assistance and encouragement provided by many people. I am fu11 of gratitude for all the support I. was glven. First and foremost, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my supervisor,. Associate Professor Hiroyuki Imai for his invaluable and insightfu1 advice and suggestions. It was big comfort for me when I got stuck with my studies. I could not have completed this thesis without him.. My gratitude is also extended to the Department of English Language teaching staff of Hyogo University of Teacher Education. They have provided me with a warm learning environment and professional instruction. Thanks to them, I could build a foundation ofmy research.. I am sincerely gratefu1 the staff and fellow students of CReDEEP (Communication Research & Development for Elementary English Program). This program provided me with deep understanding about foreign language activities in elementary school and the connection withjunior high school.. I also wish to thank and my fellow students and the seminar students in our English course for giving me invaluable advice and comments. In many ways I have learnt from them. My time at Hyogo University of Teacher Education was enriched by. them. I am also gratefu1 to the teachers and students of Ryonan Junior High school, who participated in this study. I thank them for their warm-hearted cooperation.. I further wish to thank Hyogo Prefectural Board ofEducation and Ryonan Junior. High School for providing me with the opportunity to study at Graduate Course of.

(4) ii. Hyogo University ofTeacher Education. I gratefu11y appreciate the financial support of grants from Benesse Corporation that made it possible to complete my thesis.. Last but not least, I would like to express my gratitude to my family members,. especially my husband and my daughter for their moral support and warm encouragements. Owing to their cooperation, I could devote myself to studying for the past two years.. '. Eirko Takeuchi. Yashiro, Hyogo December, 201 1.

(5) iii. Abstract. Vocabulary learning has been considered to be one of the major difficulties that students face when learning English. Nevertheless, a high value has not been placed on vocabulary in English classes, and it has been left to students to learn on their own.. According to the implementation of Elementary Foreign Language Activities, a smooth introduction of reading and writing is expected at the beginning ofjunior high school from the perspective of the connection of English education. This study aims to explore. the difficulties that Japanese junior high school students have in learning English vocabulary and to make some suggestions to eliminate these difficulties and enhance their vocabulary learning.. This thesis is composed of five chapters. Chapter 1 provides a review of earlier research findings. rlThe field ofvocabulary learning has been studied from various points. ofview, and a number ofearlier studies approaching the field from three angles, namely. vocabulary knowledge, the vocabulary learning process, and vocabulary learning strategies, led to the method of exploration used in this study.. Chapter 2 provides the purpose and method of this study. The research questions pursued were as follows:. 1) Do the connections among three facets of vocabulary knowledge: `meaning,' `sound', and `spelling', have distinct features or tendencies?. 2) Do the vocabulary learning strategies that students use have distinct features or. tendencies?. '. 3) Does the relationship between vocabulary knowledge and vocabulary learning strategies have distinct features or tendencies?. The participants in this research were 182 second-year students and 165.

(6) iv. third-year students at a public junior high school. The instruments for data collection. were a questionnaire on vocabulary learning strategies and a vocabulary test. The questionnaire was developed on the basis of carefu1 examinations of the relevant earlier. studies of vocabulary learning strategies. The vocabulary test was also developed for each grade to investigate students' vocabulary knowledge, focusing on the relationship. among `meaning', `sound', and `spelling'. The vocabulary used for the testing was selected using three criteria: parts of speech, syllables, and word farniliarity.. Chapter 3 provides the results and analysis. First, the vocabulary test is explored in detail. The test results are classified into five types according to the breakdowns that. occur among three facets ofvocabulary knowledge: `meaning', `sound', and `spelling.'. The breakdowns are then compared in visual and auditory reception. Various sample. groups are also extracted and compared quantitatively in both the productive and receptive phases. Next, the vocabulary learning strategy used is compared among grades and various groups. The correlation between the vocabulary test score and the strategy used is then analyzed. Finally, the open-ended questionnaire is analyzed quantitatively and qualitatively.. Chapter 4 provides a discussion of the findings suggested by the results and analysis in Chapter 3. Three or four findings are provided for each research question as follows. The findings for question 1 include the following: (1) `sound' reception was the. most difficult of all types of reception to perform successfully; (2) poor `sound'. reception caused poor `spelling' production in both grades, and also caused poor `meaning' production in the second grade; and (3) strong `meaning' reception led to strong meaning production. The findings for question 2 were as follows: (1) strategies. were used more frequently by the students whose learning had improved than by those. whose learning did not improve yet; (2) the `romoji' strategy' was used by many.

(7) v. students, but it was not related to their test scores; (3) `memorizing with meaning' led to. high test scores; and (4) the `writing rehearsal strategy' was used by many students, but. the `just looking strategy' was used only by the students who showed improved learning.. The findings for question 3 included: (1) three strategies, namely `self-testing', `connection to synonym or antonyms', and `writing rehearsal with meaning', showed correlations with test scores; (2) the correlations changed step-by-step in accordance. with students' progress; and (3) the actual use of strategies differed from the correlations; in other words, students tended to use some strategies that were ineffective for them or not to use some strategies that were effective for them.. Chapter 5, the final chapter, summarizes the research, and offers the following pedagogical implications: First, `sound' should be considered more important in English. classes and tests. In order to enhance students' `sound' reception, more `sound' use should be practiced in English classes and tests. Next, vocabulary learning strategies should be taught in accordance with students' learning development. Concrete examples of effective strategy use should be shown to students, which could direct students to adopt more effective vocabulary-learning strategies. Moreover, the administration of the. questionnaire on strategy use itself would encourage students to focus on vocabulary learning strategies.. This chapter concludes with a final note emphasizing the importance of teachers question on their own teaching..

(8) vi. Contents. Acknowledgements''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''i Abstract''''''''••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••t••••••••••iti Contents''''''''''''''''''''''•''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''vi List of Tables''''''''''''''''•''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''viii List of Figures''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''' ix. Introduction'''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''1. Chapter1 Earlier Literature on Vocabulary Learning'''''''•''''''''''''''5 1.1 Vocabulary Knowledge''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''5 1.2 Vocabulary Learning Process'''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''6 1.3 Vocabulary Learning Strategies''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''11. Chapter2 PresentStudy'''''''•'''''''''''''••••'•••'''''''''''''''''16 2.1 Aim of the Study'''''••'••'•''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''16. 2.2 Method'''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''16 2.2.1 Participants''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''16 2.2.2 Questiormaire'''''''''''''''''''''''•'''''''''''''''''''''''''17 2.2.3 Vocabulary Test'''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''18 2.3 Data Collection'''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''20. Chapter 3 Results and Analysis''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''21 3.1 Vocabulary Test''''''''''•'''''''''''''''•••'''''''''''•''''''''''21.

(9) vii. 3.1.1 Overall Analysis''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''21. 3.1.2 Group Analysis''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''•''''''''''''27 3.2 Vocabulary Learning Strategies''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''32 3.3 Relationship between Strategy Use and Test Score'''''''''''''''''''''''38 3.4 Descriptions of Vocabulary Learning Strategies'''''''''''''''''''''''''40. Chapter4 Discussion•••••••••••''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''45. Chapter 5 Conclusion''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''50. Reference'••''''''''''•'••'••''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''52. Appendix 1 Questionnaire Items (Japanese Version) '''''''''''''''''''''''56 Appendix 2 Questionnaire Items (English Version) ''''''''''''''''''''''''57. Appendix 3 Vocabulary Test for Third Grade'''''''''''''''''''''''''''''58 Appendix4 Vocabulary Test for Second Grade'''''''''''''''''''''''''''''59 Appendix 5 Mean of Strategy Use by Extracted Groups'''''''''''''''''''''60 Appendix 6 Strategy Use Test between Upper and Lower Groups''''''''''''''62 Appendix 7 Correlation Coeffricients by Extracted Groups''''''''''''''''''''63. Appendix 8 Correlation CoeffTicients Test'''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''65 Appendix 9 Categorized Descriptions of Strategy Use in Third Grade' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' '66. Appendix 10 Categorized Descriptions of Strategy Use in Second Grade'''''''''68.

(10) viii. List of Tables. Table 1. Sample of Vocabulary Test'•'•''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''18. Table 2. Correct Answers in Vocabulary Test'''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''21. Table 3. Correct Answers in Reception and Production'•'''''''''''''''''''''22. Table 4. Five Types of Answers'''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''25. Table 5. Breakdowns in the Production Process of `Meaning', `Sound', and `Spelling'. ••••••••••••26 Table' 6. Correct Answers in Reception and Production by Upper and Lower Groups. ••••••••••••28 Table 7. Correct Answers in Reception and Production by S-S and M-S Breakdowns. Groups'''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''29 Table 8. Breakdowns and Correct Answers by S-S and M-S Breakdowns Groups. ••••••••••••29 Table 9. Correct Answers in Reception and Production by Romoji and No RomaJ'i. Groups'''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''30 Table 10. Correct Answers in Reception and Production by Unbalanced Reception. Groups'''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''31 Table 11. The Use of Vocabulary Learning Strategies'''''''''''''''''''''''''33. Table 12. Differences ofDescriptions between Upper and Lower Groups' ''''''''41. Table 13. The Number of Strategy Items in Descriptions''''''''''''''''''''''41. Table 14. The Number of Statements about Self-testing Strategy''''''''''''''''43.

(11) iX. List of Figures. Figure 1. Dual-route Model'''''''''''''''''''•'''''''''''''''''''''''''8. Figure 2. Dual Access Model''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''8. Figure 3. Vocabulary Acquisition Process Model'•'''''''''''''''''''''''''''9. Figure 4. Vocabulary Learning Process of Japanese Junior High School Students. ----------11 Figure 5. Five Types of Answers in Three Kinds of Receptions''''''''''''''''23. Figure 6. Mean of Strategy Use by Upper and Lower Groups'''•''''''''''''''35. Figure 7. Total Use of Memory Strategies by Upper and Lower Groups'''''''''37. Figure 8. Correlation Between Strategy Use and Correct Answers by Upper and. Lower Groups'''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''39 Figure 9. Correlation Between Total Use ofMemory Strategies and Correct Answers. by Upper and Lower Groups'''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''39.

(12) 1. Introduction. English education in Japan has been revised many times over its long history. This year, in a major change, Foreign Language Activities were implemented for both. fifth and sixth grade students at elementary schools. Moreover, next year English lessons at junior high schools are going to increase from three lessons to four lessons a. week. Accordingly, the number of English words that junior high school students are. expected to learn is also going to increase from 900 to 1200. These increases are. expected to improve students' learning, but they might be a burden for students, especially with regard to the amount ofvocabulary they will be expected to learn. These. changes would require teachers to reconsider their teaching methods. Actually, the new course of study (Ministry ofEducation, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, 2008). suggests that teachers take into consideration students' English Activity learning experiences in elementary school in creating their syllabi.. For many years, many students have thought of English as a diffricult school subject. Benesse (2009) indicates that English is ranked second lowest among subjects that students prefer. This study also shows that many students have lost their motivation. to learn English before summer vacation in the first grade. In this period, at the beginning of their English education, students encounter a large number of English words, and they are puzzled by the relationships between the sounds and spellings of English words. Learning vocabulary in English requires a patient effort. The emphasis on and diff7iculty of vocabulary learning is believed to be a cause of the decline of students' motivation in the beginning period. Kageura (1997) asserts that junior high. school students show puzzlement when learning English vocabulary.. The study by Benesse also suggests that teachers and students have different.

(13) 2. perceptions regarding vocabulary learning. The following factors are considered by teachers to contribute to students' perception of the difficulty of learning English: first,. learning vocabulary; second, learning routine; and third, a lack of general learning. motivation. Whereas from the students' perspective, the factors that make learning. English diff7icult are the following: first, learning grammar; second, achieving satisfactory test results gaining; and third, writing sentences. As Negishi (2009) pointed. out, the students who are not satisfied with their test results consider English to be a. diffTicult subject, because they consider English to be a subject to be encountered on tests and entrance examinations. The higher-ranking factors in students' perceptions are. related to tests or examinations, and the lower-ranking factors, for example, learning vocabulary, speaking, or reading, are not related to tests or examinations. On the other hand, from the teachers' perspective, the skills that they usually assess in tests are taught. adequately in English classes, and the skills that they usually do not assess in tests are not taught adequately. Vocabulary learning is one ofthe latter skills. Teachers usually do. not take vocabulary seriously in tests, and thus students usually do not care if they improve their vocabulary knowledge or not.. Foreign Language Activities were implemented in elementary schools in 2011, and students at elementary schools are expected to be familiar with understanding spoken English and speaking in English. They start to learn to read and write in English. at junior high schools. Gradual instruction in these four skills is expected to allow. students to successfu11y learn English. Moreover, spiral learning of the meaning of expressions is expected over the same period, for many of the expressions taught are the. same between the Foreign Language Activities taught in elementary school and the English taught in the first grade at junior high schools. As the course of study (2008) suggests that students' English learning experience in elementary schools must be taken.

(14) 3. into consideration, teachers at junior high schools must take a new look at their methods. of instruction, especially the introduction of the reading and writing of words. Sakai (2009) points out that a smooth transition from oral lessons in elementary schools to visual lessons in junior high schools is needed. He also mentions that the relationship. between pronunciation and spelling should be taught at junior high schools. Fukazawa, et al. (2009) found that the education involving listening and speaking but not reading. and writing at the elementary-school level does not necessarily reduce teachers' or students' burden in the beginning period ofjunior high school. Introducing the reading and writing ofEnglish words injunior high school should be reconsidered.. There are many studies on the connection between English education in elementary school and that in junior high school. For example, Nakamura, Suematsu, and Hayashida (2009) focus on vocabulary and report that students who experienced English activities in elementary school can link the sounds of words with their meaning directly, and they can do the same when they encounter new words at junior high school.. Also, many studies have been done from the perspective of vocabulary learning. For example, Nation (2001) states that the `learning burden' ofa word is the amount of effort required to learn it. However, there are not many studies regarding the vocabulary. learning of Japanese junior high school students. Using strategies is necessary for students to learn vocabulary successfu11y. All students seem to use strategies when they. learn vocabulary, whether they are conscious of it or not. Furthermore, not only the strategy use but the detailed process in which vocabulary learning takes place need to be. explored. Clarifying the process in which students learn vocabulary may work to ease the students' burden when learning vocabulary.. In this study we investigate both the strategies for and the detailed process of vocabulary learning. The research was conducted in two ways. One was a questionnaire.

(15) 4. on vocabulary learning strategies in order to collect information on the vocabulary 'learning strategies used by Japanese junior high school students, and the other was a vocabulary proficiency test to assess the vocabulary knowledge of Japanese junior high. school students. Based on the results of these studies, we discuss the relationships between the strategies for learning vocabulary and the detailed process under which this. leaming takes place, and assess the influence of these relationships on vocabulary learning..

(16) 5. Chapter 1 Earlier Literature en Vocabulary Learning. 1.IVocabulary Knowledge Prior to our investigation, we need to review definitions of vocabulary learning. and vocabulary knowledge. Nation (2001) argues that `knowing a word' does not simply. mean knowing its spelling and meaning. He took a systematic approach to vocabulary learning involving many elements which are categorized as elements of three aspects:. form, meaning, and use. Each aspect contains three parts as follows. Form can be divided into spoken, written, and word parts. Meaning can be divided into form and. meaning, concept and referents, and associations. Use is composed of grammatical imctions, collocations, and constraints on use. In addition, the receptive and productive. modes are subordinated to each of the nine parts of vocabulary knowledge. Nation defines the receptive and productive modes as follows. The receptive mode refers to. how leamers try to comprehend what they receive as language input from others through listening or reading, and the productive mode refers to language that is produced by speaking or writing to convey meaning to others. He also states that the terms receptive and productive apply to a variety of kinds of language knowledge and use, therefore when they are applied to vocabulary, these terms cover all the aspects of. what is involved in knowing a word.. On the other hand, Schmitt (2000) claims that framing mastery of a word only in terms of receptive versus productive knowledge is far too crude. He emphasizes that people learn words receptively first and later achieve productive knowledge in general, but in language learning there are usually exceptions, as in the case of knowing a word productively at least for the purpose of speaking but not receptively in the written mode..

(17) 6. He points out that the different types of word knowledge are not necessarily learned at. the same time, accordingly unless the word is completely unlmown or fully acquired,. different word knowledge wM exist at various degrees of mastery. In addition, he summarizes that we need to consider the various facets of knowing a word, and the mechanics ofvocabulary learning are stili something of a mystery.. What do Japanesejunior high school students think about vocabulary knowledge? They usually use the terms `pronunciation', `spelling', and `meaning' in relation to learning vocabulary. These three terms seem to correspond, respectively, to `spoken',. `written', and `form and meaning' in Nation's (2001) approach to vocabulary knowledge. These three elements represent a small portion of all nine elements used in. Nation's approach. Schmitt (2000) states that "vocabulary acquisition must be incremental, as it is clearly impossible to gain immediate mastery of all these word. knowledge simultaneously" (p. 5). Japanese junior high school students are just. beginning to learn English, and in view of their EFL context, three elements of vocabulary knowledge, namely pronunciation, spelling, and meaning, each of which contains both a receptive mode and a productive mode, might be adequate for the purposes ofour investigation oftheir learning process.. 1.2 Vocabulary Learning Process How do we recognize a word; its sound, spelling, and meaning? What is going on in the vocabulary learning process, especially at the beginning stage? From a cognitive linguistics perspective, Kadota and Ikemura (2006) propose that a `word' consists of its. `form' as acode and its `meaning', which is indicated by the form. The `form' as acode consists of `sound' and the `spelling' corresponding to the sound. In other words, the. correspondence of three elements, namely `meaning', `sound', and `form', forms a.

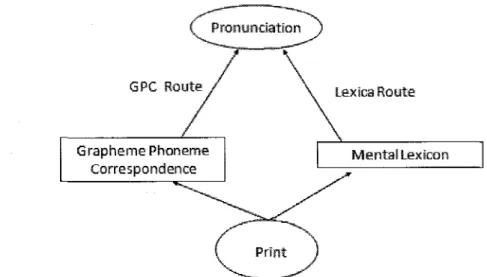

(18) 7. `word'. This is a primary definition of `word', but surprisingly it is the same as Japanese. junior high school students' understanding of `word'.. Kadota and Ikemura (2006) state that there is a close connection between `spelling' and `phoneme', because `spelling' is a written expression of `sound'. But. Kadota and Noro (2001) point out that English orthography has irregular and opaque. grapheme-phoneme correspondence rules in comparison with other alphabetic languages. So it is difficult and takes a long time to learn English grapheme-phoneme. correspondence (GPC). Noro (2004) states that Japanese orthography has two systems: syllabic, which corresponds to kona letters, and logographic, which corresponds to konji characters. Thus, it is far different from English orthography. Therefore, many Japanese. junior high school students have some trouble reading English letters aloud properly.. This difficulty stems from the difficulty of learning English orthography. Noro also. '. assets that Japanese learners of English should learn to improve their phonological. awareness, and lessons on GPC, such as phonics, should be introduced in general lessons at school.. Again, how do we recognize a word? Ellis (1995) states that there is no single process of learning a word. First we recognize it as a word and next enter it into our mental lexicon, but there are several specialized lexicons for different channels of input. or output. Kadota and Ikemura (2006) present a dual-route model that shows the process from the visual input to the speech output (see Figure 1). One route is the lexical route. in which learners recognize a whole word and access their mental lexicon to produce its. pronunciation. This route is used for words that have irregular GPC rules. The other. route is the GPC route in which spelling is converted into pronunciation by using one-to-one correspondence rules without going through the mental lexicon. This route is. used for words that have regular GPC rules. Both routes are used simultaneously to.

(19) 8. arrive at the pronunciation of a visual input word.. Moreover, Kadota and Ikemura (2006) goes on to propose a dual-access model that presents the process from the visual input to semantic comprehension (see Figure 2). There are three different views based on this model. One is the phonological mediation theory, which postulates that leamers first access orthographic representation or graphic. ttt tt tt t tt ttttttttt '. pifoywa, waelatlEl.M. GPC gevate. Si zRxEcRRgvate tt tt. ' G;caoPrhvZ[:SgPfikdee:':eM'e wtevetaiLex}coit. t ttt tt ttt tt t'... r ptfnt . .. '... ... '. Figure 1. Dual-route model. (Kadota and Ikemura, 2006, p.187). Se•mend•ci Repre/seRteti•sft. R'gsutLxirf lf7 R..3. g{eB .. phasoEggieei <Ril2i}llllllliEISI:IIIg> '' oythagraphie gepge'e/se-"tgt}en < iiitil fdressgd Redits Repre'se-wtatinzz. fi t tttt tttt. .. .V.l.sual gnptEt. Figure 2.. Dual-access model. (Kadota and Ikemura, 2006, p.i95).

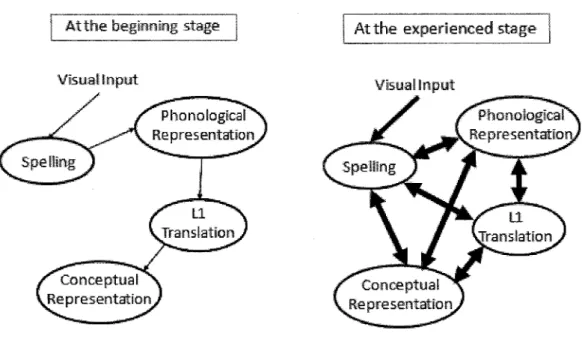

(20) 9. representation instantly after the visual input of a word, next access the phonological representation, and finally access the semantic representation. Another view is the visual. access theory, which holds that learners go through only the orthographic representation or graphic representation before arriving at the semantic representation. In this theory,. learners gain direct access to meaning without going through a phonological representation. The last view is the dual-access theory, which holds that learners use. both phonological mediation and visual access simultaneously. Kadota and Ikemura support the last theory with evidence from their studies.. Kadota and Ikemura (2006) also propose L2 vocabulary acquisition process models (see Figure 3). The models indicate the change of vocabulary acquisition process from the beginning stage to the experienced stage. At the beginning stage, learners who received visual input access a conceptual representation along one route. via spelling, phonological representation, and Ll translation serially. But at the. AXke baglitwtag stage. VIsuaStwpvat ,... ... ...... At the•. experiEmce•di stage. XilseeaEinpagk. . ,' PkoReEogecal. ''. Pkoko}ogi,caI. RegeresentatEo. '''gb.5iEi.g''' i'''' Repifgsentgiie. spREggng ttt tt ttt tt tt. '. Sl '-. •-. TfageslatEcn. E3 ''. 3vafislatrEog. ttt tttttt t tt. CencEptesel RgpvesentaboR. Figure 3. Vocabulary acquisition process mod. Conceptngei RgprEsenitatEoR. el. (Kadota and Ikemura, 2006, p.257).

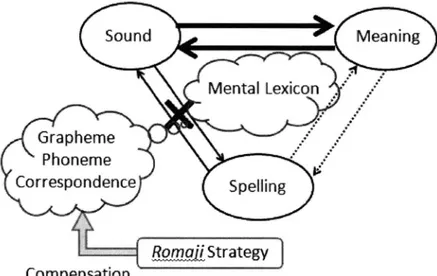

(21) 10. experienced stage, learners who received visual input can access the phonological representation, Ll translation, and conceptual representation in random order, or can directly access the conceptual representation without going through one serial route.. '. Experienced learners are ultimately able to activate any representation freely and speedily.. With respect to Japanese junior high school students, they are beginners in English vocabulary learning, and according to L2 vocabulary acquisition process models, after they receive visual input, they access conceptual representation along one route via spelling, phonological representation, and Ll translation serially. Moreover, students necessarily access an orthographic representation or graphic representation in. accordance with phonological mediation theory. Direct access, without going through a phonological representation, is not available to beginners. If we apply these theories to. Japanese junior high school students with limited vocabulary knowledge, we can show their vocabulary learning process simply with a triangle (see Figure 4). According to the. theories, direct access between `meaning' and `spelling' is impossible except for sight words, so students necessarily access `sound' in order to produce `spelling' or `meaning'.. However, a serious concern arises. Between `sound' and `spelling', both a mental lexicon and GPC are necessary, but learners at the beginning stage have little or no mental lexicon or GPC. It is likely to become a burden for students not only to produce `sound', `meaning', or `spelling', but also to receive them.. In this study we would like to explore the students' vocabulary learning process. by posing the question of how students produce `meaning' via `sound' when they receive a `spelling'. We explore this question in terms of three aspects of students'. vocabulary knowledge..

(22) 11. Sound. Meaning --"-. Mental texicon ---. ----. -;t. --. .. Grapherne. "i. -t-". -t--. ,"". --. Pheneme Cerrespondence. -"-. ---t. .. .. --. ti. Spelling. ttl{zmntL Strategy. Compensation. Figure 4. Vocabulary learning process ofJapanesejunior high school students.. 1.3 Vocabulary Learning Strategies. Before focusing on vocabulary learning strategies we will review language learning strategies. Language learning strategies have been regarded to be an important. factor in the process of language learning, and many researchers have defined and proposed many different language learning strategies in the last few decades. Oxford (1990), one of the leading scholars in the field of language learning strategies, defined. learning strategies as operations employed by the learner to aid in the acquisition, storage, retrieval, and use of information. She also argued that learning strategies are. specific actions taken by the learner to make learning easier, faster, more enjoyable, more self-directed, more effective, and more transferable to new situations. O'Malley. and Chamot (1990) also defined language learning strategies as special thoughts or. behaviors that individuals use to comprehend or retain new information. These definitions are similar to definitions of vocabulary learning strategies. Nation (2001).

(23) 12. stated that vocabulary learning strategies are a subset of language learning strategies which in turn are a subset of general language learning strategies. He also states that. most vocabulary learning strategies can be applied to a wide range of vocabulary and are usefu1 at all stages of vocabulary learning, and they also allow learners to assume. control of their learning. Gu and Johnson (1996) claimed that the most successfu1 learners were those who actively drew on a wide range ofvocabulary learning strategies,. and propose that they need a strategy for controlling their strategy use. According to. these views, we are not able to look into vocabulary learning without examining vocabulary learning strategies. In other words, vocabulary learning strategies likely play. an important role in vocabulary leaming.. There have been a number of attempts to develop a classification scheme of vocabulary learning strategies. Oxford (1990) proposed one of the most comprehensive detailed schemes of six strategies, classified as direct or indirect. The direct strategies. included memory, cognitive, and compensation strategies. The indirect strategies included metacognitive, affective, and social strategies. Based on this classification, she. produced an instrument to assess learning strategies, the Strategy Inventory for. Language Learning (SILL). This instmment has been used by a great number of researchers including Oxford herself, and it remains worthy of referencing today. But. we had better also take account of variables affecting the use of language learning strategies. For example, Takeuchi (2003) pointed out that strategies frequently used by. learners in an Asian English as a Foreign Language (EFL) context differ drastically. from those in the North American English as a Second Language (ESL) context. Schnitt (1997) stated that since strategies may be culture-specific, different findings. '. may be derived from the observation ofpeople from different Ll backgrounds. Thus, we should refer to other earlier studies that regarded strategy use in EFL contexts..

(24) 13. Gu and Johnson (1996) conducted research aiming to establish the vocabulary learning strategies used by Chinese university learners of English. They developed a. substantial number of categories of vocabulary iearning strategies: beliefs about vocabulary learning, metacognitive regulation, guessing strategies, dictionary strategies,. note-taking strategies, memory strategies (encoding), and activation strategies. They. summarized that "contrary to popular beliefs about Asian learners, the participants. generally did not dwell on memorization, and reported using more meaning-oriented strategies than rote strategies in learning vocabulary" (p. 668). They proposed that "learners should use memory strategies that aim for retaining word-meaning pairs with. other caution, if at all, and should complement them with other fu11y contextualized strategies" (p. 669).. Mizumoto and Takeuchi (2009) conducted research aiming to examine the effectiveness of explicit instruction in vocabulary learning strategies with Japanese EFL university students. The strategies they taught were divided broadly into two categories:. cognitive strategies that measure learners' intentional vocabulary learning behaviors,. and metacognitive strategies that coordinate their strategic behaviors. These subcategories were divided into six categories: self-management, input-seeking, imagery, writing rehearsal, oral rehearsal, and association. They concluded that strategy. instruction is more beneficial to less-effective learners, and suggested that "the instruction of vocabulary learning strategies should be further employed and expanded in normal classroom settings" (p. 443).. Furthermore, we would like to review other studies that examined learners in earlier learning stages, such as high school students or junior high school students. Schmitt (1997) examined a total of600 Japanesejunior and senior high school students,. university students, and company employees to determine whether they use the.

(25) 14. strategies and whether they are usefu1. He investigated many strategies and proposed his. own taxonomy of vocabulary learning strategies. They are determination strategies, social strategies, memory strategies, cognitive strategies, and metacognitive strategies.. In his research a number of interesting findings arose. One of them was the change of strategy use over time. As the participants became older, they came to use strategies that. were less frequently used by younger learners and ceased to use the strategies which younger people were found to employ. The data for `Trends ofvocabulary strategy use' (p. 223) clearly show which strategies younger learners use more and which strategies they use less.. Kudo (1999) examined a total of more than 800 Japanese senior high school students. He conducted research aiming to describe the strategy use among Japanese senior high school students and systematically categorize those strategies as in the SILL,. a systematic classification scheme of learning strategies based on empirical data. He. classified around 50 strategies into just four categories: social strategies, memory strategies, cognitive strategies, and metacognitive strategies. He states that "many findings of the questionnaire turned out to be quite congruent with those of Sclmitt's. (1997) descriptive studies and Oxford's (1990) classification schemes" (p. 30). The strategies most frequently used involved rote learning, and the strategies less commonly. used were those that involved deeper cognitive processing, such as the key word technique and semantic mapping. Consequently he suggested that "students should be exposed to many strategies" and "if they can find strategies suitable to them and actually use them, this might increase their vocabulary size" tp. 30).. Hirano (2000) conducted research aiming to investigate Japanese junior high school students' awareness of their vocabulary learning strategies and explore the effects of language proficiency and sex difference on their awareness or perceptions of.

(26) 15. their vocabulary learning strategies. She focused not on a taxonomy of strategies but on. memory strategies. The total of 48 strategies includes 35 memory strategies, five activation strategies, and eight other strategies. The results revealed that four factors of vocabulary learning strategies, namely repetition factors, imagery factors, liking factors, and oral rehearsal factors, were extracted through factor analysis. Significant differences. were found among the three levels of language proficiency for three factors: repetition factors, imagery factors, and oral rehearsal factors.. These previous studies show that the use of vocabulary leaming strategies plays a. ' key role in the vocabulary learning process, and that more instruction in learning strategies should be provided to students. What strategies should be introduced to Japanese junior high school students? The learners' context and the learning context should be taken into fu11 consideration for answering this question. In this study, we explore vocabulary learning strategies and the vocabulary learning process in order to. provide students with more effective instruction and enhance students' vocabulary learning..

(27) 16. Chapter2 Present Study. 2.1 Aim of the Study It was observed in the previous chapter that vocabulary learning is a comp}icated. process, and the process seems to contain many factors that cause diflriculties for learners, especially to beginners. If teachers could provide students with more effective. instruction, the burden of learning vocabulary would be reduced, and students might. willingly learn vocabulary. In this study we explore how the learning process presents difficulties for students, and what strategies could aid in their learning. The research questions we explore in this study are the following:. 1) Do the connections among three facets of vocabulary knowledge: `meaning,' `sound', and `spelling', have distinct features or tendencies?. 2) Do the vocabulary learning strategies that students use have distinct features or. tendencies?. 3) Does the relationship between vocabulary knowledge and vocabulary learning strategies have distinct features or tendencies?. 2.2 Method 2.2.1 Participants The participants in this research were 182 second-year students from five classes. and 165 third-year students from five classes at ajunior high school in Hyogo Prefecture. They normally have four periods of English per week at school. They came. from two different elementary schools, and they experienced different elementary English activities. The participants from one elementary school experienced about 30.

(28) 17. hours in only the sixth grade. The participants from the other elementary school experienced about 10 hours in the fourth grade, and about 30 hours each in the fifth grade and the sixth grade. There were twice as many of the latter participants than the former. The differences in their experiences did not have noticeable effects in English classes from their teachers' perspective.. 2.2.2 Questionnaire The instruments used for the data collection were a questionnaire and a vocabulary. test. First, we describe the questionnaire in detail. The questionnaire on vocabulary learning strategies was developed on the basis of carefu1 examinations of relevant earlier. studies (Oxford, 1990; Gu and Johnson,1996; Sclmitt,1997; Mizumoto and Takeuchi, 2009; Kudo, 1999; Hirano, 2000). The classification scheme of the language learning strategies is divided into two categories, direct strategies and indirect strategies, based on. Oxford (1990). The direct strategies include memory strategies and association strategies, and the indirect strategies include social strategies and self-management strategies. From this perspective we could see direct and indirect strategies as cognitive and metacognitive strategies, respectively. Each of the four categories has from three to eight items, for a. total of 24 items. According to the purpose of our study, we stress memory strategies and. association strategies to investigate the process of memorizing new vocabulary; each of these categories has eight items. The category of social strategies has three items, and the. category of self-management has five items. All eight items in the memory strategies category are concerned with rote memorization, which seems to be used by most learners. in juni'or high school. Gan (2004) also stated that rote memorization seems to be important for Asian EFL learners to acquire a certain amount of vocabulary at the begiming of their English language learning process..

(29) 18. The panicipants were asked to rate the statements using a five-point Likert scale format. The scale applied to all the items and ranged from 1 (`never true for me') to 5 (`always true for me') in order to elicit answers from the participants easier. At the bottom ofthe questionnaire, one open-ended question was added. Participants were asked. to freely describe their way of leaming vocabulary, but the question was not obligatory. The questionnaire is shown in Appendix 1 in Japanese and in Appendix 2 in English.. 2.2.3 Vocabulary Test A vocabulary test for each grade was developed in order to investigate students'. vocabulary knowledge, focusing on the relationship among meaning, spelling, and sound. The test consisted of three sections: a meaning section, spelling section, and. sound section. In each section, one of these three facets of vocabulary knowledge is. presented, and the participants are required to produce the other two parts that correspond to the presented part. For example, in the meaning section, one meaning in Ll is presented as a question, and the participants are required to produce its spelling in. L2 and sound in Ll katakana. Table 1 shows sample questions for each section. Ten words were prepared for each section, and a total of 30 words were prepared for each grade. These words were selected from the textbook that the students used last year. We set three criteria for the selection. First each section had to consist of the same number. p. Table 1. Sample of Voeabulary Test Answers required to fi11 the byank. Questions. 1 Meaningsection 2 Spellingsection. 3 Soundsection. xta chair CD `...,. .. .. ( family ). ( 77;-V-). ( +z7- ) ( bird ). ( LN'!lnt ). ( ,k ).

(30) 19. of nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. The numbers of concrete nouns and abstract nouns were also equivalent. Second, each section had the same total number of syllables. Third, there were no significant differences in the word familiarity of the words in each. section. The word familiarity was based on the database that Yokokawa (2006, 2009). developed for Japanese leamers of English as a foreign language. Yokokawa (2006) defines word familiarity as one of the lexical attributes that has great influence on both. language comprehension and production, and also as the degree to which one feels that a certain word is heard or seen in hisfher daily life. The database was developed based on ratings of the familiarity of English words done in a visual manner and in an auditory. manner. We referred to the database developed in an auditory manner in the sound section of the vocabulary test, and the database developed in a visual manner in the meaning and spelling sections of the vocabulary test. Yokokawa also found that even in. non-contextualized situations, accessing the mental lexicon is infiuenced by various. factors: word length, frequency, familiarity, orthography, correspondence between spelling and pronunciation, and so on. As the vocabulary test in this study was a non-contextualized situation, we adopted the three criteria mentioned above.. This test was conducted on paper, but to investigate students' sound perception,. 10 words were tested in a listening comprehension test using an audio CD that was recorded by a native speaker of English.. In this test we assessed students' vocabulary knowledge using word meaning, sound, and spelling. The `meaning' simply refers to the Ll translation and does not include the conceptual understanding of the word. Schmitt and Schmitt (1995) stated that `word pairs'; the L2 target word and its basic Ll translation, may be good for the. initial learning of a word's meaning. The `sound' refers to the pronunciation, which. participants were required to write down in Ll katakana on paper, and the CD sound.

(31) 20. The. that the students listened. to.. participants were required. to write. the L2 speiling,. which the. down on paper. The vocabulary test. is shown in. `spell ing' refers. to. Appendices 3 and 4.. 2.3 Data Collection The vocabulary test and the questionnaire were administered in May 2011 under the supervision of the participants' English teachers. The participants were required to. take these two assessments in one English class. Before the administration, the participants were informed and assured by the teachers that: 1) their responses would not affect their grades; 2) their anonymity was assured; and 3) their responses would be. used for research only. All data were collected in two days in each grade and analyzed in quantity and in quality..

(32) 21. Chapter 3 Results and Analysis. 3.1 Vocabulary Test 3.1.1 Overall Analysis The following results were obtained by multiple statistical analysis in order to. explore the connections among the three phases of vocabulary knowledge. Table 2 shows the results of the vocabulary test. A comparison between grades shows that the third graders exhibited a higher number oftotal correct answers, and that the difference. was significant (p < .OOI). This dominance of the third graders was shown in each `meaning' reception, `spelling' reception, and `sound' reception, with significant difference (p < .OOI), as well as in the subcategories of `meaning' production, `sound' production, and `spelling' production.. With regard to receptive knowledge, the number of correct answers for `spelling'. Table 2 Correct Answers in Veca Receptive. bittary Test. Productive. 3rd grade (R - 165). 2nd grade (n = 182). 6.95. 2.15. 4.86. SD 280 288. `Meaning'reception `Spelling' `Meaning' in Ll. 6.19. 256. 4.20. 2.91. 724. 2.30. 6.02. 2.90. in L2 `Sound'in Ll. 6.32. 2.52. 5.l2. 2.67. `Spelling'reception. `Meaning' `Spelling' in L2. in Ll `Sound' in Ll. csound' in L2. Mean. SD. Mean. 5.43. 2.72. 3.54. 6.78. 2.45. 5.57. 2.82. `Spelling' in L2. 4.81. 259. 2.32. 2.42. `Meaning' in Ll. 6.32. 2.14. 325. 2.56. `Sound'reception. 5.56. 2.49. 2.78. 253. Total. 6.18. 2.55. 4.I8. 2.98. Note . rk' **p <DOI.. t-test. 6.38*** 7.69***. 726*** 434*** 431*** 4.44*** 9.21*** 12.l9*** l1.1l*** 8.07***.

(33) 22. reception was the highest and that for `sound' reception was the lowest in both grades, especially in the second grade, with the number ofcorrect answers for `sound' reception. significantly low. `Spelling' reception produces `sound' and `meaning' in Ll. It is. reasonable that those two productions in Ll showed higher means than other mixed productions involving Ll and L2. But in the comparison between `meaning' reception and `sound' reception in Ll and in L2, the lower mean for `sound' reception might indicate that participants could not perceive English sounds correctly.. In contrast to receptive knowledge, `sound' production was the highest and `spelling production' was the lowest in both grades (see Table 3). The high percentage for `sound' production is due to the fact that the participants were required to write. down those sounds on paper in Ll hatakana in this test. Moreover their romoji knowledge might help them to produce those sounds. The low percentage for `spelling'. production would indicate that participants have diff7iculty spelling out L2 words correctly.. No significant differences were revealed between reception and production with regard to `meaning'. On the other hand, significant differences were revealed between. reception and production with respect to `sound' and `spelling'. These results might indicate that `sound' reception and `spelling' production could be areas of difficulty in. Table 3 Correet Ans}vers ilt Reeeption and Production 2nd grade. 3rd grade. Productive. Productive. R. T' l. 1. 1 Meaning. 54.3. 2 Spelling. 632. 3 Sound. 632. 48.1. Total. 632. 512. o. [lr l. l. 35.4. 69.5. 61.9. 72.4. 67.8. 51.2. 55.6. 32.5. 23.2. 4L8. 29.3. 70.9. 48.6. 42.e. 602. 55.7 27.8. 54.4.

(34) 23. vocabulary learning for students, especially the second graders.. Next, the incorrect answers on the test were analyzed. Five types of answers (A, B, C, D, and E) were possible for each act of `meaning' reception, `spelling' reception,. and `sound' reception (see Figure 5). Diagram no. 1 below shows the production process that occurs after `meaning' has been received. First, participants grasped a `meaning' in Ll and produced its `sound' correctly, and then produced its `spelling'. correctly. This is answer type A. Answer type B is the pattern in which participants failed to produce a correct `spelling' after producing the correct `sound'. Answer type C. is the pattern in which participants failed to produce both `sound' and `spelling' correctly. Answer type D is the pattern in which participants failed to produce the. correct `sound', but succeeded in producing the correct `spelling'. In this type,. No.1 No.2. --x-----------+x-, ... ' '.'" '' ii./. .'.'.'.'i.'. ' gg, l,l, ei"""i."'''"''" `"uai''''''}{egrl.tEig s:..l.\ild .-:tw k'''''''i'''' Meli.,r, ti-.l. , .1'/. Lri• .A ,.• :N'x.ll,l,/ '///l)Nx%. ... '. 'i''" Spelkn ' Seeljn No.3 r. -thi-xgi:ptirpt-r"x-Y--"s""i-k. Sownd. C. k-. Meanillg. tN.. be A A... ": ,, ., s,. ii" '. Spelhn. Figure 5.. Five types of answers in three kinds ofreception..

(35) 24. participants might be considered to have directly produced the `spelling' without going via `sound'. Answer type E is the pattern in which participants produced the `sound' and. `spelling' that did not correspond to the meaning. Diagram no. 2 above shows the production process that occurs after `spelling' has been received. All five types of answers are the same as those described for `meaning' reception except that the arrows. go in the opposite direction. Diagram no. 3 shows the production process that occurs `sound' has been received. All five types in no. 3 are different from those in nos. 1 and 2. in which `sound' plays a mediation role in the production of `spelling' or `meaning', and. '. the procedures take one-way routes. In no. 3, the participants first listened to `sound' and produced `meaning' and `spelling' directly. The procedures in no. 3 take two routes, both starting from `sound'.. Table 4 shows the results of the percentages of answers falling into the five answer types for each type of reception. The percentage with both answers correct and the percentage with both answers incorrect were significantly different between the two grades. In the third grade, the percentage with both answers correct (53.20/o) was much higher than the percentage with both answers incorrect (21 .80/o). However, in the second. grade the percentage with both answers correct (34.50/o) was lower than the percentage. with both answers incorrect (45.20/o). A total of more than 650/o of answers were incorrect among the second graders. This might indicate that the beginners who have been learning English for just one year are still on the way to acquiring the basis of English vocabulary learning.. The differences between grades were also seen in each type of reception. There were no significEmt differences (F (2, 492) = O.26"'S') among the three types of reception. (IC:22.80/o, 2C:21.60/o, 3C:21.00/o) in the percentages of the third graders giving both. incorrect answers. The second graders, however, showed significant differences (F (2,.

(36) 25. 543) = 21.85, p < .OOI) among the three types of reception in terms of the percentage giving both answers incorrectly, with the highest percentage of both incorrect answers in `sound' reception (IC:55.40/o) and the lowest in `spelling' reception (2C:34.80/o).. These differences among each type of reception are believed to depend on whether the participants were required to produce the `spelling' or not. The fact that the highest percentage corresponded to `sound' reception might indicate that it was diffTicult for students to receive `sound' correctly. However, as the results of the third graders showed, learning experience can reduce those diffriculties.. Next, the patterns of breakdovvns were categorized. The breakdowns occurred in. Table 4. Five TJIpes ofAnswers. Meaning. -: .9 > es. Spelling. e. bri Sound 5. <. Spelling O. IB:. Spelling Å~. Sound O Sound O. 1C:. Spelling Å~. Solmd Å~. 1D:. Spelling O. 1E:. S elling A Soimd A Meaning O Sound O Meaning Å~ Sound O. 2A: 2B: 2C: 2D:. No te.. 3A: 3B: 3C:. Sound Å~. Meaning Å~ Sound Å~. Meaning O Sound x Meanin A Sound A Spelling O Meaning O Spelling Å~ Meaning O Spelling Å~. Meaning Å~. 3D:. Spelling O. Meaning Å~. 3E:. S elling A. Meaning A. A:. Total. Ans O/o. 1A:. 2E:. -x. ew3dd. Productive. Receptive. C:. Both Both. o Å~. o: A:. 878 268 376 18 le7 IO08 186 355 34 64 746 297 347 47 213 2632 1078. -2dd Ans O/o. 53.3 16.3. 22.8 l.1. 65 612 1l.3. 21.6 2.1 3.9. 452 18.0. 21.0. 28 12.9. 532 2l.8. 33.6. 190 633 25. 1O.4. 66 364 227 1008 58 164 1879 2465. cerrect amswer, Å~: mcorrect answer, two productions are correctly cormected but different from reception, Ans : for each type ofreception there were total of165e answers in3rd grade, and l 82O ansvgrers in 2nd grade.. 609 275 824 35 70 906. 15.2. 45.4 1.9 3.9. 498 34.8 1 .4. 3.6 2e.o l2.5. 55A 32 9.0 34.5. 452.

(37) 26. the production of `meaning', `spelling', and `sound'. Table 5 shows the breakdowns in. gaining access between `spelling' and `sound' and between `meaning' and `sound'. Visual reception represents `meaning' reception and `spelling' reception, while auditory reception represents `sound' reception.. The results showed-that the percentages of breakdowns in the second grade were significantly higher than those in third grade. The breakdowns in auditory perception. were especially high, especially in second grade. Moreover, in the second grade, the. breakdowns between `spelling' and `sound' (henceforth S-S breakdowns) showed no significant difference from the breakdowns between `meaning' and `sound' (henceforth M-S breakdowns) in both visual reception and auditory reception. In the third grade, the. breakdowns in visual reception were the same as in second grade, but in the auditory reception the percentage of S-S breakdowns was significantly higher than that of M-S. Tab1e5 Breakdewns in the Production thocess of `Meaning ',. Breakdowns. `Sound ',. and `Spetling '. w3dd O/. t. A2}g-g!{!gsldade. O/, t. t. Visual reception. I between`spelling'and`sound' E between `me aning' and `sound' Auditory reception. M between`spelling'and`sound' IV between`meaning'aRd`sotmd'. 21.9 20.9. O.60. 275 308. -1.33. 39.0 23.9. I058***. 67.8 58.5. l51. 459***. 41.0 40.1. O.34. -2.80**•. -4 .62***. -7.39*** t8.39***. Total reception. V between`spelling'and`sound' VI between`meanino'and`sound' No te.. 27.6 21.9. I =IB+2C+2D+2E,. g=lC+1D+lE+2B, M=3B+3C, IV=-3D+3C. , V =IB+2C+2D+2E+B3+3C, (see Fi.eq]re 3.1 and Table 3.3), VI==1C+1D+lE+2B+3D+3C ** p <Dl, **• *p <.OOI.. -6.79*+ ** •-. 897***.

(38) 27. breakdowns. In short, the second graders have problems with auditory reception, and it is diff7icult for them to produce `meaning' and `spelling' by listening to `sound'. Third. graders also have problems with auditory reception, but only in producing `spelling', not in producing `meaning'. Students are believed to have difficulty in listening to and. comprehending spoken English, especially in producing `spelling' from `sound' without. visual help. On the other hand, the difficulty in producing `meaning' from `sound' without visual help seemed to decline gradually as the students progressed.. 3.1.2 Groups Analysis In order to explore more features of the process of learning vocabulary, six sample groups were extracted: the upper group, lower group, M-S breakdowns group, S-S breakdowns group, roma]'i interference group, and no roma]'i interference group. The upper group and lower group consisted of the participants whose vocabulary test. scores were in the top 100/o and bottom 100/o of all scores, for their scores were. conspicuously higher or lower than others. The M-S breakdowns group and S-S breakdowns group consisted of the participants whose breakdowns in the vocabulary test were in the top about 100/o in each, as the same with the upper and lower groups. The romal-i interference group (henceforth romoji group) was defined as including those. showing three instances of romoji interference in `sound' production on the vocabulary test. The no romoji interference group (henceforth no romoji group) included those who showed no romal-i interference in `sound' production on the vocabulary test. Regarding the no romal'i group, only the third grade group was sampled, because over half of the. participants in second grade showed no romoji interference, and so the sampling was assumed to be unsuitable in the second grade.. All groups showed the general tendency (see Table 3) in reception and in.

(39) 28. production. As shown in the analysis of the overall features earlier in this chapter, diff7iculties in `sound' reception and `spelling' production appeared in all groups.. In a comparison of the upper and lower groups (see Table 6), the mean test score ofthe upper group was not very different between the third grade (50.8) and the second grade (47.6), but that in the lower group in the second grade (5.6) was much lower than. that in the third grade (15.6). Moreover the percentages were not very different among the three types ofreception and three types ofproduction in the upper groups. But in the. lower groups, large differences were seen. The difficulties of `sound' reception and `spelling' production were revealed, especially for students in the second grade.. In a comparison of the S-S breakdowns group and M-S breakdowns group (see Table 7 and Table 8), both groups showed the same features as the overall tendency for all breakdowns. In the second grade, the means of both breakdowns and correct answers. Table 6 Cerreet Answers in Reeeption and Prodttction by Upper and Lower Groups. Rece tive. 3rd grade. 2nd grade. Productive. Productive Total. i. o/6. Total. 1. Upper group. 1 Meaning 2 Spelling. 3 Seund Total. - 82.8 90.9 86.9 85.6 - 89.7 87.7 82.5 76.3 - 79.4 84.1 79.5 90.3 (n = 32, score = 50.8). - 78.5 89.l 84.7 - 93.8 69.7 60.3 -. 83.8 89.3. 65.0. 77.2 69.4 91.5 (n = 34, score == 47.6). Lower .qroup. 1 Meaning 2 Spelling. 3 Sound Total. - l3.i 38.4 25.8 23.1 - 35.9 29.5 35.e IO.6 - 22.8. 29.l ll.9 372 (n = 32, score = 15.6). - 5.7 13.7 l3A - ,l8D. 5A O9.4 2.9 15.9 (n = 35, score = 5.6). 9.7. 15.7. 27.

(40) 29. ' showed no significant difference between the S-S breakdowns group and the M-S breakdowns group. In the third grade, the mean of breakdowns showed a significant difference between the two groups, but the mean of the correct answers did not. In a. comparison between the grades, the S-S breakdowns groups showed no significant. Table 7. CorreetAnswers in Reeeptien and Prqduction by S-S and M-S Breakdo",ns Groups 2nd grade. 3rd grade. Productive. Productive. Rec tive. Total. l. l. g/o. Total. Breakdowns between `spelling' and `soimd' (S-S) group. l Meaning. - 30.e 55.3 29.8. 2 Spellmg. 45.0 - 55.9 30.6 50.6 22.5 - 26.1 32.3 l3.9 40.3 -. 3 Sound Total. 12.4 33.5. 23.0. 23.2. - 26.8. 25.e. 21.4. 6.5 -. l3.9. 22.3. 9.5 3Ql (n = 32, score = l7.3). (n = 37, score = i2.4). Breakdowns between `meaning' and `sound' (M-S) group. - 41.0 59.8 34.3 54.1 - 70.5 43.3 59.e 37.1 - 33.8 38.7 25.l 47.6 -. 1 Meaning 2 Spelling. 3 Sound Total. 5.6 9.2 22.4 IO.8. l6.6. - 332. 525.4 21.2. 7.4. 27.8 8.0. (n = 25, score = 8.6). (n =41, score = 22.3). Table 8 Breakdowns and CorrectAns"vers b.v S-S and MLS Breakdewns Gromps. rw2dd -3dd S-S ou M-S ou S-S ou M-S ou Breakdowns. 9.53. 8.37. 2.29*. t-test. l731. correct answers. -i.93. p<.05,. *+ ts'. )p <.Ol , *\'. x1. S-S ou M-S ou. 9.2e. O.35. 8.64. l.98. -1.83. O.32. 22.27. t-test Note. "'. 9.35. 7J<DOi.. 12.37 1.47. 5Al *• **.

(41) 30. differences in either the mean breakdowns or correct answers, but the M-S breakdowns groups showed a significant difference in the mean number of correct answers. These results might indicate that breakdowns between `meaning' and `sound' at the beginning stage are a problem in learning vocabulary.. In a comparison between the romoji group and the no romoji group (see Table 9), as the sampling process that was previously mentioned indicated, the results of the. '. romal'i and no romoji groups might suggest that second graders rarely use the romal'i strategy to produce `sound'; in other words they have not yet reached the stage of using. the romoji strategy. But the third graders were able to use the strategy with many instances of interference. The number of instances of interference in the third grade ranged from three to nine (mean 4.2), and that in the second grade ranged from two to four (mean 2.3). Moreover, no significant difference (t = -O.82 "'S') in test scores was. Table 9 Correct Answers in Reception and Produetion by Remaji and No romaji Greups. Rece tive. 3rd grade. 2nd grade. Productive. Productive Total. 1. e/6. Tot 1. 1. Roma7'i interference group. IMeaning -. 47.1 66.5 56.8. 2 Spelling 562. - 66.5 61.3. 49.2. 3 Sound 60.0 Total 58.3. 41.3 - 50.9 44.2 66.5 -. 32.8. 292 51.6. 41.0. No romqli interference group. 3 Sound 51.7 62.4 Total 61.4 54.3 67.9 (n = 29, score - 36.7). 23.2 55.8 (n = 25, score = 24.0). (n = 52, score - 33.8). IMeaning - 56.9 68.3 w 2 Spelling 60.3 - 67.6. - 60.0 17.2 -. 62.6. 64.0 57.1. 40.4 54.6. 25.0.

(42) 31. observed between the romoji group (33.8) and the no romoji group (36.7). These scores are close to the mean of the third grade score (37.1). Each group included participants in. both the upper and lower groups. These results might suggest that romoji interference is not related to students' achievement.. In order to explore more features of the process of learning vocabulary, another six sample groups were derived using the criterion of an unbalanced number of correct answers among the three types of reception (see Table 10). The `meaning' < `spelling'. (henceforth Me<Sp) group is the group whose score for `spelling' reception was much. higher than that for `meaning' reception. The `meaning' > `spelling' (henceforth Me>Sp) group is the group showing the opposite tendency. Four other groups, namely the `meaning' < 'sound' (henceforth Me<So) group, `meaning' > `sound' (henceforth Me>So) group, `spelling' < `sound' thenceforth Sp<So) group, and `spelling' > `sound'. (henceforth Sp>So) group, were extracted in the same way. In the third grade, all of. Table 10 CorrectAnswers in Rece tien and Preduetion by Unbalaneed Rece. tion Gromps Productlve. Productive. Rece tive. Total. l. 1 Meaning. 3 Sound Total. - 32.8 68.3 57.8 36.7 63.1 34.7. 53.9 43.3 78.3 73.3. - 47.2 66.1 -. 34.1. 2 Spelling. 54.1. 3 Sound Total. 72.9. 55.3. 63.5. 44.7. 53.3. 2 Spelling. 46.7. 3 Sound Total. so.e. 63.3. 63.3. 58.3. 71.3 61.9 65.0 70.3. 869 82.8 67.5 63.l. - 66.6 77.2 -. 58.2. 72.0 -. 85.5 78.5 81.0 76.5. 64.1. 56.0 38.0. - 47.0. 64D 54.8. 83.3 -. - 54.7 78.0 -. 70.0 62.3. 43.8. 62.4. 57.9. wS>S(15oe365). 65.0. 59.2. 55.0. 50.8 71.7. 60.0. - 78.8 58.8 -. - 71.5. 53.5. Sp < So (n = l2, score = 36.3). 1 Meaning. Total. Me > So (n = 20, score = 40.4). Me < So (n = 17, score = 33.2). 1 Meaning. l. Me > Sp (n = 16, score = 42.5). Me < Sp (n :: 18, score = 32.8). 2 Spelling. o/o. se.o 2s.o 64.0 41.3. 84.0 81D. - 39.0. 77.0 -.

(43) 32. these groups could be extracted, but in the second grade one group could not be extracted because of the low score for `sound' reception. Sampling the second grade students was abandoned, and only samples from the third grade were explored.. All groups showed almost the same percentages of correct answers in `meaning' production (63-650/o); nevertheless two other types of production showed different. percentages in each group. All groups also showed a tendency for lower `sound' reception to result in lower `spelling' production, and for higher `sound' reception to. result in higher `spelling' production. This tendency might confirm the overall trend of the correct answers in reception and production.. With regard to the number of correct answers, the Me>Sp group showed the highest score, and the Me>So group showed the second-highest score. In contrast, the. Me<Sp group showed the lowest score, and the Me<So group showed the second-lowest score. This might indicate that strong `meaning' reception could be related to high test scores.. 3.2 Vocabulary Learning Strategies. The following results were obtained from the items of the questionnaire on vocabulary learning strategies. In the analysis of the results, all data were re-divided into three groups using a scale from 1 to 5: Section 1. `I never or seldom use this strategy' (scores of 1 and 2, respectively; `never or. seldom true for me'). Section 2. `I sometimes use this strategy' (score of 3; `sometimes true for me').. Section 3. `I always or nearly always use this strategy' (scores of4 and 5, respectively;. `always or nearly always or often true for me').. Table 11 shows the overall results of vocabulary learning strategy use. The.

(44) 33. strategy use was more frequent in the third grade than in the second grade, but only social strategies were used more frequently in the second grade than in the third grade.. In both grades self-management strategies were used the most frequently, and social strategies were used the most infrequently. In particular, `romal'i" (Ql5) was always or nearly always used the most by 81e/o ofthe third graders and 680/o ofthe second graders. `Self-testing' (Q7) was used the second-most by 470/o of the third graders and 360/o of. Table 11 The Use of Vocabularpt Learning Strategies Strategies. Mean. -as Ql. 'g Q2 c,) Q3 totai. -g Q4. .i g Q5. a• g 86,. E Q8 totai. Q9 QIO = .9 Qll •g Qi2. 2 Q13 i Q14. <ta. Ql5 Q16 total. Ql7 Ql8. b Ql9. 8. Q2o s- 82•i. Q23 Q24 total. TOTAL. 2nd grade (n==182). 3rd grade (nF165). sD sl o/e s2 o/, s3 o/,. 2.26 O.94 60.6 2.19 1.06 63.6 1.88 1.l5 75.8. 2.11 66.7 2.72 1.44 49.7 3.00 l.33 37.6 2.74 1.30 44.8 3.24 l.38 30.9 2.66 1.l2 41.2. 2.87 40.8. MeanSD SI O/, S2 O/, Ll3. 26.2 32.6. 2.l7 2.20 2.29 2.22 2.79 2.68 2.98 2.77 2.64 2.77. 9.l 18. 1.76. l.l3. l.l7 l.38. 30.3 8.5 25.5 10.9 12.l 11.5 22.6 IO.3 19.4 30.9 27.3 35.2. 26.7 285 212 47.3 36.4 212. 1.45 O.77 88.5 2.l5 1.23 66.7 2.68 1.29 48.5 2.73 1.22 43.6 2.48 1.15 54.5. l7.0 l5.8. L88. 20.0 315 29.l 27.3 26.l 19.4. 2.32 2.27 2.14. 1.86 1-02 76A. l7.0 6.7. 1.81. 4.20 1D9 9.7. 9.7 80.6. 1.68 l.02 80D. 3.32 1.21 255 232 1.22 64.8. 227 1.l8 642 2D5 l.07 685 1.92 094 76.4 153 e.77 89.l. 615 l48. 23.1. -2.97**. 19.4. l6.l. 23.6. l .47. 64.3 45.6 51.1. l38. 385. 24.7. 1 .49. 50.5 5l.6 47.5 82.4 74.7 65.4. l32. 30.8 29.7 36.8 36.3 23.6 31.4. l.40 l.43. }28. 2l.O 6.6. -1.69. 3.03** O.18. ll5. 251*. l7.0. 225. 12.l. 3.41*** 2.73**. l3.7 13.2. 6.6. O.47. 68.l. 2.33*. 12.l. 165. -2.57*. 1A4 346. l4.4 23.1. IAI. 45.1. 24.2. 205 412 302. 40.l 68.7 73.1 80.2. 242. 35.7. 3.40*** 3.77*** 3.10**. 18.1. l32. O.99. l8.l. 8.8 8.2 7.l. 3.10** 2.91**. 60. 1.43. l .25. 632. 1.l8 1.07. 65.4 79.1. lA2 127. l8.l. 20.6 IO.3. 1.7l. l.06. 182 55 79 3.0. 1.75 l.66. 1D7 802 099 82.4. 20.6 24.8. 224. Note. xp<.05. **p<.Ol, *x*p<.OOI.. 242. -O.46. 2.l6*. 21.4. 188. 2.35. l92. -2.95** 2.06*. l8.8 l70. 2.53 54A 2.51 545 21.0 24.2. 19.2. l3.7 13.2 l9.8. l.27 l.l9 1.l5. 2.40 585 3.58 1.23 l9.4 25.5 55.2 327 124 27.3. O.80 -O.08. 64.8 66.5. 30.9 41.8 26.7 47.3 16.4 18.2. 13.3 6.7. 242 lID l4.3. 1.l3. 3.88 2.00 2.26 3.09 2.73 2.90 2.l9. 17.7 23.7. t- test. s3 o/,. 7l.4 65.0. 63.0 60.6. lO.4 12.6 l1.5. l1.0. l78 l8.8 175 2L7. 156.

(45) 34. the second graders. `Writing rehearsal' (Ql7, Ql8, and Ql9) was used the third-most by 42-550/o ofthe third graders and 3041e/o ofthe second graders.. In a comparison between grades, most strategies were used significantly more frequently in the third grade than in the second grade, as mentioned above. In particular,. eight items were significantly used more frequently in the third grade. They included. `writing rehearsal' (Q17, Q18, and Q19) in the memory strategy, `visual and oral rehearsal' (Q21 and Q22) also in the memory strategy, `association with already known. word' (Q12 and Q13) in the association strategy, and `self-testing' (Q7) in the self-management strategy. In contrast, just three items were significantly used more frequently in the second grade. They were `family support' (Q3), `drawing its picture' (Q9), and `using alphabet sound' (Q16).. The frequent use of self-management strategies and memory strategies might show that students are making great efforts to learn vocabulary. The most frequent use. of the `romaJ'i' strategy would indicate that they have acquired neither grapheme-phoneme correspondence rules nor a mental lexicon. In order to explore more features of strategy use in learning vocabulary, 12 groups in the third grade and 11 groups in the second grade were compared. The detailed results. are shown in Appendix 5.. All groups showed almost the same features as an overall tendency, except for one feature: the group that produced more correct answers used more strategies. For example, a descending order of strategy use in the third grade was shown as follows: the. upper group (mean of correct answers: 50.8), no romal'i group (36.7), romoji group (33.8), M-S breakdowns group (22.3), S-S breakdowns group (17.3), and lower group (15.6). But one different feature was observed in the second graders. The upper group (25.8) and the romoji group (24.0) used strategies more frequently than the other three.

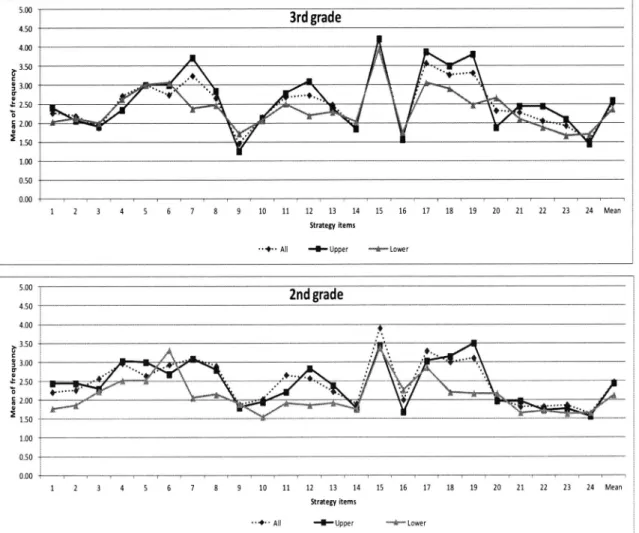

(46) 35. groups in proportion to their test scores, but the romoji group used more than the upper. group out of proportion to their test scores. It might be reasonable to assume that students who use many strategies would also use many romaiji strategies, and that those. students who make an effort to learn vocabulary would succeed in producing correct answers. As strategy use was likely to be connected to the number of correct answers, the. upper and lower groups were compared (see Figure 6 and Appendix 6) in terms of strategy use. Total strategy use was more frequent in the upper group than in the lower group in both the third grade (t = 2.17,p <. 05) and the second grade (t = 2.03,p < .05). s.oo. 3rdgrade. 4.50. l,: tny. l,.. '. ""'""t,. .. --. g'L2.so. "•. ..,. v. ----;. "--. ."--. o E 2.oo. --t-i ... {. .. 1.so IIget. o,oo. 1 2 3 4 5 S 7 8 9 le 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Mean Strategy items. ''"" All -Upper --ke-eLower s,oo. 2nd grade. 4,so l 4,OO ' :v. if. ! F •:i. 350. E. ,-l-. :-. ----. 3,OO -t. -+. .. .,.. :. -"---. --. 2.SO. .I. ["1-t-2,OO. ii. --. ,. .. i-+. t, '. -t-. -,. t. --. --j-. ---. ISO 1,OO O,50 o.oo. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 strategy items `'"" All +Upper ""-sbe"'- Lower. Figure 6. Mean ofstrategy use by upper and lower groups.. 18 19 20 21 !2 13 24 Meen.

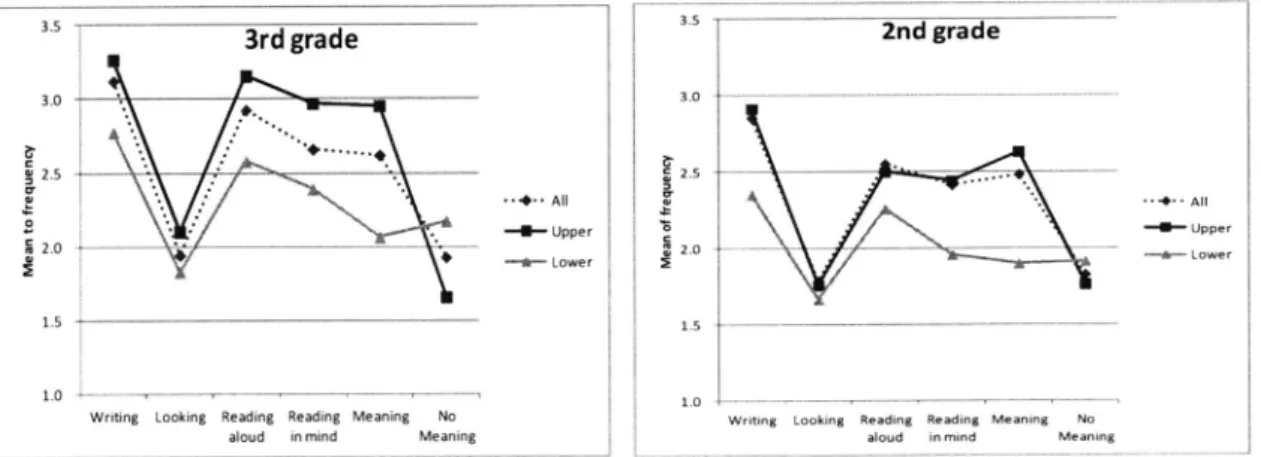

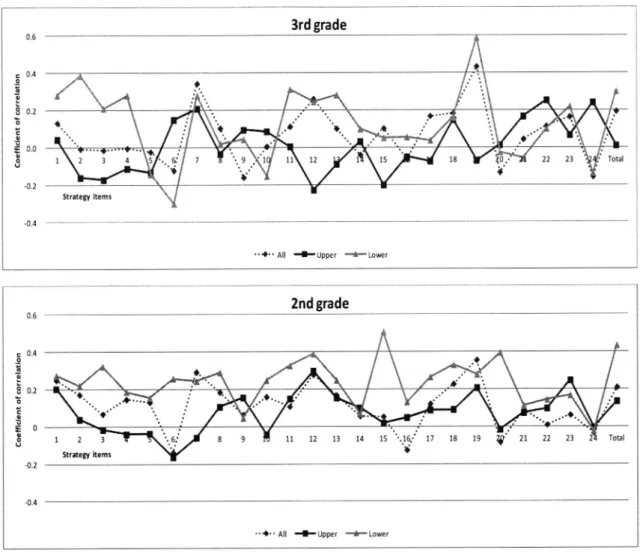

(47) 36. participants. In panicular, three items were used more frequently in the upper group than in the lower group in both grades: `self-testing' (Q7) in the third grade (t = 4.95,p. < .OOI) and the second grade (t == 3.13,p < .Ol), `connection to synonyms or antonyms' (Q12) in the third grade (t = 3.26,p <. Ol) and the second grade (t = 3.19,p < .Ol), and. `writing rehearsal with meaning' (Q19) in the third grade (t = 4.82, p < .OOI) and the second grade (t == 5.13,p < .OO1). Other items showed different features in each grade.. In the third grade, only one more item was used more frequently in the upper group than in the lower group, namely `writing with oral rehearsal' (Q17) (t -- 2.78, p. < .Ol), and two other items were used more in the lower group than in the upper group, namely `drawing its picture' (Q9) (t = -2.18, p < .05) and `writing rehearsal without meaning' (Q20) (t = -2.66,p < .05). In the second grade, four items were used more in the upper group than in the lower group: `writing rehearsal with sound in mind' (Q18) (t = 5.13,p < .Ol), `devising a good way' (Q8) (t - 2.33,p < .05), `quiz with friends' (Ql) (t = 2.59,p < .05), and `talking about strategies with friends' (Q2) (t = 2.17,p < .05).. These results might suggest that the three items that were used more frequently in the upper groups of both grades were effective strategies for learning vocabulary, but those strategies might be diffricult for lower group students to use.. Regarding the differences between grades, it is reasonable to assume that association strategies would help the second graders, and even the third graders in the lower group relied on pictures. In employing memory strategies, the third graders in the. lower group seemed to have just looked at the words without writing. However, the third graders in the upper group tended to write words many times with oral repetition.. On the other hand, the second grades in the upper group tended to write words many times with the sound in mind. In order to explore more features ofthe use of memory. strategies, all memory strategy items were re-categorized into six items from the.

図

関連したドキュメント

A tendency toward dependence was seen in 15.9% of the total population of students, and was higher for 2nd and 3rd grade junior high school students and among girls. Children with

Required environmental education in junior high school for pro-environmental behavior in Indonesia:.. a perspective on parents’ household sanitation situations and teachers’

Information gathering from the mothers by the students was a basic learning tool for their future partaking in community health promotion activity. To be able to conduct

Compared to working adults, junior high school students, and high school students who have a

The hypothesis of Hawkins & Hattori 2006 does not predict the failure of the successive cyclic wh-movement like 13; the [uFoc*] feature in the left periphery of an embedded

The purpose of the Graduate School of Humanities program in Japanese Humanities is to help students acquire expertise in the field of humanities, including sufficient

The course aims to help students develop an interest in topics about the mental and physical development and learning process of preschoolers, elementary school children and

In addition, by longitudinal guidance intervention research, it becomes significantly higher values in all of the learning objectives in junior high school, Rules and