日本人英語学習者による'on'の習得のプロトタイプ的分析とプロトタイプ的対照分析の可能性(2)

全文

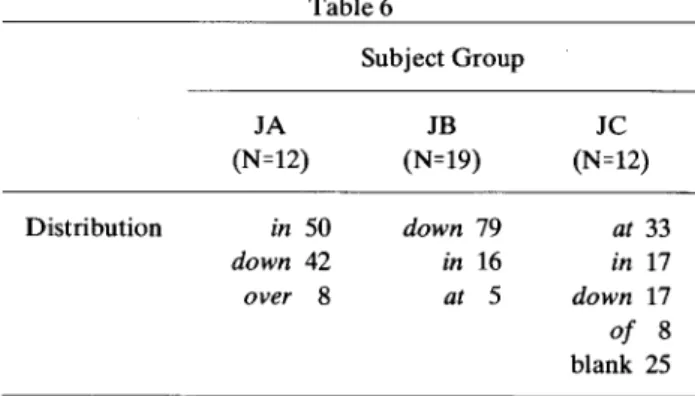

(2) EE!. ways of expressing the same intended meaning in. correct). The proactive pattern goes with the prediction. Japanese: `sofaa (sofa) no (attributive) ue (on) ni. of the prototype theory, and the retroactive pattern. (locative) suwaru (sit)'and `sofaa ni suwaru.'If the. against it. The statistical analysis was earned out on the. subject selects the latter, which is more common in. rate of the number of retroactive responses against the. Japanese, for the translation equivalent, he or she may. number of proactive responses. Results are presented in. translate the locative by a/ as the most neutral place. Table 8.. indicator in English.. Table 8. These response patterns indicate how easily Japanese subjects are led into e汀ors by seemingly trivial factors in spite of their correct knowledge attested to in the other e VI >, T. sentence (la). Truly, their interlanguages are permeable. hNrnt}-in. (Adjemian, 1976). Generalizing the same reasoning to every other sentence type, it can be conjectured that the difference in the percentage of correct response in each sentence pair. 1. 2. n.s.. may reflect a fluctuation of the potential knowledge possessed by the subject due to nonessential factors. It. !p<.05. may be reasonable, therefore, to adopt the position that the subject can be judged to possess the knowledge of on in a given sentence type if he or she made the correct. Table 8 Results of Multiple Comparisons of Scores between Any Pair of Sentence Types. response in at least one of the two sentences of the type. Reanalysis of the data with this new position yields the. We have three pairs which do not show significance:. response patterns shown in Table 7.. pairs 1-2, 3-4, and 4-5. For the first pair, the ceiling effect may explain the result. For the second and the third. Tabe7. pairs, it may be helpful to recognize that each contains a larger number of retroactive responses than the other. Sentence Type. pairs do, thus, causing non-significance. Importantly, Subj ect. 1. 2. 3. about half of these responses were produced by subjects. 4. Group. 榊n(iNncnOni-HfS ‖H. ㈱fr- ̄<mSvOo¥¥Oo 1. ㈱MSt-糾7 日HH. JAB C. O0 4ノ 58 ′7 h8 U5 0 日HHH. Ift. oO oO oO aO ノO ′ノ O O 111. JB. 帥㈱㈱㈱0 -i-(-hy-Ii-I. NS JA. in the JC group. With these subjects, it was the correct. Table 7 Accuracy of Responses in Each Sentence Type by Each Subject Group. response to (4b) (`spider on the ceiling') in the second pair (3-4), and to (5a) (`apples on the branch') in the third pair (4-5) that caused the retroactive pattern. As a result, these subjects showed correct knowledge of the type of sentence in spite of their failure in the preceding type in the hierarchical prototype organization, thus,. violatii鳩the lmphcational expectation. It might be that these subjects somehow possessed these (4b and 5a) or. In order to test statistical significance of the. similar expressions separately and independently of other. difference in accuracy rates between any pair of sentence. uses of on, hindering the knowledge of on in these. types matched according to their hierarchical prototype. expressions from being properly arranged in the. organization presented in Table 3 m the Part 1 of this. hierarchical organization of various uses of on. In other. article, multiple comparisons using McNemar test were. words, these expressions may have been learned as set. conducted for the scores of all Japanese subjects (Note. phrases.. that type 7 is excluded in this analysis.) Notice that in any. With these considerations, it might be safe to. of the pairs, four response patterns can occur (correct-. conclude that Table 8 successfully shows a general. correct, correct-wrong, wrong-correct, wrong-wrong),. response pattern by Japanese subjects which reflects the. two of which are of concern here: the proactive pattern. prototype organization proposed in the Part 1 of this. (correcトwrong) and the retroactive pattern (wrong-. article..

(3) A Prototype Analysis of the Learning of On by Japanese Learners of English and the Potentiality of Prototype Contrastive Analysis (Part 2). 45. The second part of the first hypothesis is concerned. tend to possess knowledge of various uses of on. with an implicational hierarchical response pattern in. somewhat independently and separately without a. each subject. The rates of those subjects in each group. coherent perspective on the usage of on.. who broke the expected implicational relationship. From the discussion above, the first hypothesis can be. somewhere in the hierarchy were 17% for the JA group,. said to have been confirmed. In general terms, Japanese. 26% for the JB group, and 34% for the JC group. The. learners of English learn and possess knowledge of. results indicate that far more than half of subjects in each. various uses of on according to the prototype. group exhibited the expected imphcational response. organization proposed.. pattern. This is more evident in the more proficient groups. Conversely, the less proficient groups showed. 5. Results and Discussion onthe Second Hypothesis. more divergence from the expected norm. Again this. Japanese subjects were expected to overextend on to. may indicate the possibility that less proficient learners. cases where other prepositions are required, pushed by. Tabe9. Sentence No.. Sentence No.. Subj ect Group D. istributio. NS. JA. JB. 8. t. 0.  ̄. over. -. ノ. t. ′. H. from. O. -. o. O. i r. S O 蝣. n. i. ". r. *. N. j. 3. others. <. ォ. 3. on. Hサshs,. up. io<r>¥n 1. 100. 1. above. O. i. 1. NHNi-It-(. C. N. 2. IT)T-Il-IT-1. (. ノ. blank. m サ ^ - r t 蝣 * H. O. others. 2. up. O. on. 3. 41. C. 59. D istributio n NS JA JB ォ. r-^hootn^h 4 3 1. above. n. Subject Group. -. No.. 10. t. Sentence. *. blank. Sentence. No.. Subj ect Group D. istri. butio 1. n. 00. NS 64. Subject Group. JA. JB. JC. D. 32. istri. over. ′ U. blank. Sentence. No.. 12. on up others blank. Sentence. No.. Distribution. NS. JA. 5. above. JB. 7. 1. 59. ノ. 0. 1. 1. 3. (N*-<(N(N. 叫. 3. up. 0. 8. ′. on. 3. 4. 41. 3. 2. 4 0. 6. ノ. b ank. 2. others. 3. If100ITrtrt 5 1 2. 2史jt-iinaフ!-U. iHC>r-ir>. ォo¥¥omi/^m 5 1 1. 35. 13. Subject Group. D ist ribution NS JA JB 59. JC. 41. 12. Subject Group. above. JB. l. h. 17. 53. A. J. 26. J. つ. 32. 3. 2. 17. On. 3 ! h ) 1 8. up. 88. NS. OOCIU-)M. above. bution. lー"L >m?2 i 2 4. above. others. ll.

(4) 46. (Table 9, continued). Sentence. No.. 14. Sentence. No.. 15. Subj ect Group. Subject Group. D istributio n NS JA JB. D ist ri bution NS J A JB h m. s. t. o. t. f. 29. 1 s. c. j. o. <. o. < *. o. ′. フ. 蝣 c. y. o f. O. ′. ∠. ノ. T. O. U. rsk. フ. n. h. 2. n. 岬霊. n. on. * - i m h n. 71. o. h. above. c. over. 5. t. n 1. HNQO¥fl¥Crfi 34. r. U. 33. tHtH-^-^-Ii-I. 53. 史 4. 35. 1. 65. 8 1. above. ). Table 9 Response Distribution (%) by Each Subject Group for Sentences (8)-(15). the usage of Japanese ue which happens to correspond to. predictions were made concerning the learning process of. on in terms of their respective prototypes.. these prepositions by Japanese learners. Reiterating. Results of the eight distractor sentences which were included to test the possibility of transfer are presented in. them here in more concrete terms, we can propose the following learning criteria:. Table 9 in terms of response distribution. (1) whether or not oVeris learned as a lexical item. We can distinguish the following general tendencies:. (2) whether or not aboveislearned as a le立ical item (3) whether or not the prototype uses of over and. (1) For the NS group, responses are limited to over and!or above, and we see no evidence of confusion with. above are learned as is clearly shown u- the response patterns of(9) and (10) by the NS group. on except for one case in sentence (12). We can also see. (4) whether or not the respective semantic fields of. from the response patterns in (9) and (10) that these two. over, above, on and up are properly separated with. sentences are recognized as the respective prototypes of. respect to the semantic field of we. above and over. (2) In all Japanese groups, responses tend to include o? and up as well as over and above. (from in (9) can be. (5) whether or not the partial correspondence in the semantic fields between ue and each of these English prepositions is recognized. interpreted as an interference error from kara in Japanese, which roughly corresponds to from. This is because a commoner expression for the intended. Applying these criteria to each subject group, we have the results shown in Table 10.. meaning of (9) in Japanese is 'kaimen (sea level) kara Table 10. (from)').. Criteria. (3) Compared to the JA group, the JB group shows a marked decrease in responses with above, and correspondingly a marked increase in responses with. 5. +. +. ±. ±. 一. 一. 一. 一. above. However, an expected increase of on reflecting. + + ± 一. a very low percentage in responses with either over or. + + +. (4) Comparing to the JA group, the JC group shows. 2<cQU. either on or up.. 4. the decrease can only be seen in three sentences (12, 14 and 15). Up is rarely used. Instead, this group shows a. + (complete fulfillment of the criterion). marked increase in random responses as is indicated by. ア(partial fulfillment of the criterion). `others including non-response shown by `blank.'. - (non-fulfillment of the criterion) Table 10 Five Criteria of Compa!血on and the Characteristics. How can we explain the results? Earlier, three. of Each Subject Group.

(5) A Prototype Analysis of the Learning of On by Japanese Learners of English and the Potentiality of Prototype Contrastive Analysis (Part 2). 47. Table 10 clearly shows how each subject group differs in. semantic field of ue are learned, on is recognized as a. terms of these criteria. A more detailed discussion is. member of these lexical items. This motivates relaxation. needed, however, to confirm the validity of the second. of the precautionary mechanism formed in Stage 1,. hypothesis concerning the possibility of overextension of. leading to overextension of on. This may correspond to. on. In the JA group, overextension of on is limited to a. the JB group as shown in Table 10: while above has not. few cases (ll and 13). This welcome restriction might be. been learned well, over has been learned in this group,. a result of the fact that the vocabulary items over and. and overextension of on appears as if to compensate for. above have already been learned and their respective. the lack of the preposition aboVe・. semantic fields have been identified to some extent.. Stage 4: In learning from the second perspective,. In the JB group, at least one vocabulary item, over,. when all the lexical items dividing the semantic field of ue. has been learned, but above has not yet been learned. are learned, on is assigned its proper semantic field, and. well. As a result, this group shows an increase in. its overextension stops. This stage may roughly. response with overextended on in every sentence. This is. correspond to the JA group in Table 10.. what the second hypothesis predicts.. From the discussion above concerning the second. Since not only above but also over have not yet been. hypothesis, we may say that the hypothesis can be. learned by the JC group, it was expected that this group. confirmed with some modification. Interference from we. would show evidence of overextension of on more. in the form of overextension of on is not simple and. extensively than the JB group. This is confirmed,. straightforward. It's overextension is a result of complex. however, only in three sentences (12, 14 and 15); in the. phenomena involving two interactional learning. other sentences confusion predominates. Although it is. processes: division of the semantic field of ue by several. difficult to make out reasons why subjects in the JC. English prepositions, and proper assignment of the. group did not easily rely on on in responding to these. semantic field of each preposition to the parts which ue. sentences, some kind of restrictive mechanism can be. can and cannot cover, especially in the case of on.. assumed to be working concerning reliance on on, which is discussed below. Fundamentally, Japanese learners of English must recognize the following two concepts in learning on:. (1) Some uses of on have relational meanings which fall outside the semantic field of we.. 6. Conclusion and Pedagogical Implications As a conclusion to this experimental study, we can make the following claims:. (1) Japanese learners of English must realize that there are uses of on which ue does not match, while at. (2) The semantic field of ue contains relational. the same time they have to learn there are uses of ue. meanings which require different prepositions in English. which must be expressed in English with prepositions. other than on.. other than On. (2) As far as its physical uses are concerned,. From the two perspectives of learning, the following stages of development can be supposed:. learning of on proceeds along the prototype hierarchical organization of this preposition. Since the prototype use of on matches that of ue, its learning is quite easy for. Stage 1: In learning based on the first perspective, a. Japanese learners of English. But other uses of on which. precautionary attitude is nourished in the learner with. deviate from the prototype and thus fall outside the. respect to the use of on in relation to that ofue.. semantic field of ue are difficult to learn. The degree of. Stage 2: In learning from the second perspective, if. difficulty reflects the degree of deviation.. English lexical items dividing the semantic field of we. (3) over and above must be learned along with on. have not yet been learned, the precautionary mechanism. as lexical items dividing the semantic field of ue. The. in Stagel extends its influence here and the use of on is. learning order of these prepositions for Japanese learners. restricted. This stage may corresponds to the JC group. might be on - over - above.. depicted in Table 10.. (4) Interference from we can determine the. Stage 3: In learning based on the second. mechanism of overextension of on according to the. perspective, if some of these lexical items dividing the. learning stage reflecting the interactional processes.

(6) SB. between division of the semantic field of ue by several. relearned analytically and consolidated after gaining. English prepositions and proper establishment of. essential understanding of the usage of the preposition.. semantic correspondences between ue and each of these prepositions.. References Adjemian, C. (1976). On the nature of interlanguage systems.. We can also identify the following pedagogical implications for Japanese learners of English:. Lenguage Learning, 26, 297-320. Bowerman, M. L. (1977). The acquisition of word meaning: An investigation of some current conflicts. In N. Waterson and C. Snow (Eds.), The Development of. (1) In order to promote better learning of physical uses of on, Japanese learners should be provided not. Communication (pp- 263-287). New York: Wiley. Clark, H. H. (1973). The language-as-fixed-effect fallacy: A critique of language statistics in psychological research.. only with its prototype but also with its penpheral types. Since its prototype matches that of ue, learning of on. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 12, 335-359.. with its prototype alone can motivate both. Eckman, F. R., Bell, L., & Nelson, D. (1988). On the. underextension and overextension of on: underextension. generalization of relative clause instruction in the. in the case where its Japanese equivalent does not. acquisition of English as a second language, Applied Lingui∫tics, 9, 1-20.. require ue, and overextension in the type whose Japanese. Hartford, B. Y. (1989). Prototype effects in non-native. equivalent needs we. Learning of on with its peripheral. English: Object-coding in verbs of saying. World. types can potentially motivate the recognition of the fundamental difference in the core meanings between on. Englishes, 8, 97-117. Inatsugu, M. (1991). A Contrastive analysis ofprototypicality in Japanese and English with special reference to "cut". and ue. This may contribute to better learning of on and,. and "kiru", and the prepositional usage "on". thus, lead to avoidance of under- and overextension of. Unpublished master s thesis, Hyogo University of. this preposition. Moreover, it is generally confirmed in the markedness theory that learning of marked members can implicate learning of less marked members (Eckman et al., 1988). Thus, it is expected that learning of on with its marked (peripheral) type can accelerate learning of its less marked (prototypical) types. This has been attested to, although preliminary, in an experimental study with Japanese learners of English (Inatsugu, 1991).. Education, Japan. Rosch, E. (1973). On the internal structure of perceptual categories. In T. M. Moor (Ed.), Cognitive Development and the Acquisition of Language (pp. Ill144). New York: Academic. Yamaoka, T. (1988). A semantic and prototype discussion of the `be easy to V structure: A possible explanation of its acquisition process. Applied Linguistics , 9, 385-401. Yamaoka, T. (1991). A prototype discussion of the acquisition of English prepositions: The case of the. (2) Learning of over, above and up along with on. acquisition of `on'by Japanese learners of English (in. will also motivate better learning of on. Learning of these. Japanese). Annals of Educational Research, 36, 193198.. prepositions with their respective prototypes will. Yamaoka, T. (1992). A prototype analysis of second language. necessarily lead to proper demarcation of the semantic. acquisition: Potentiality of prototype contrastive. field of we. Since all the prototypes of these prepositions have a semantic feature of `higherness'in common, which is the core meaning of we, the learning of them will necessarily motivate division of the semantic field of ue, which in turn will lead to proper recognition of the semantic field of on. (3) Identification of the essential semantic feature of on through learning its various physical uses can help learning and/or consolidating knowledge of its figurative uses. A coherent perspective can develop from the physical and prototype to the figurative and peripheral, but it can not be expected to proceed in the opposite direction. Although functional and communicative urgency of some 6gurative uses may override the logical order of learning in terms of markedness, they can be. analysis (in Japanese). Report, 36, 4-9. de Villiers, J. G. (1980). The process of rule learning in English: A new look. In K. E. Nelson (Ed.), Children's Language (pp. 1-44). New York: Wiley..

(7) A Prototype Analysis of the Learning of On by Japanese Learners of English and the Potentiality of Prototype Contrastive Analysis (Part 2). 49. 日本人英語学習者による`on'の習得のプロトタイプ的分析と プロトタイプ的対照分析の可能性(2) 山岡俊比古. 英語前置詞`on'の日本人英語学習者による習得を,この前置詞のさまざまな用法のプロトタイプ論的分析によって得 られる階層構造によって説明できることを実験的に明らかにし,プロトタイプ的手法の有効性を提示することを目的と する。この実験の前提としての理論的整備と,実験の実施までを扱った第1部を受けて,第2部としての本論文では, 実験結果を示し,プロトタイプ論によってこの前置詞の習得過程を説明できることを明らかにした。また,被験者の誤 答分析から,英語の`over, `above', `up'の用法をプロトタイプとして学び,それを「上」のプロトタイプと比較的に 対照することが, `on'の正確な習得を動機づけることと,その過般的誤りを説明するためには,このようなプロトタイ プ的対照分析が必須となることを示した。.

(8)

図

関連したドキュメント

If condition (2) holds then no line intersects all the segments AB, BC, DE, EA (if such line exists then it also intersects the segment CD by condition (2) which is impossible due

Let X be a smooth projective variety defined over an algebraically closed field k of positive characteristic.. By our assumption the image of f contains

This approach is not limited to classical solutions of the characteristic system of ordinary differential equations, but can be extended to more general solution concepts in ODE

Kilbas; Conditions of the existence of a classical solution of a Cauchy type problem for the diffusion equation with the Riemann-Liouville partial derivative, Differential Equations,

Then it follows immediately from a suitable version of “Hensel’s Lemma” [cf., e.g., the argument of [4], Lemma 2.1] that S may be obtained, as the notation suggests, as the m A

To derive a weak formulation of (1.1)–(1.8), we first assume that the functions v, p, θ and c are a classical solution of our problem. 33]) and substitute the Neumann boundary

Classical definitions of locally complete intersection (l.c.i.) homomor- phisms of commutative rings are limited to maps that are essentially of finite type, or flat.. The

Yin, “Global existence and blow-up phenomena for an integrable two-component Camassa-Holm shallow water system,” Journal of Differential Equations, vol.. Yin, “Global weak