REPORT FROM THE COMMITTEE OF THE JAPANESE SOCIETY FOR

TUBERCULOSIS: A STUDY OF TUBERCULOSIS AMONG

FOREIGNERS RESIDENT IN JAPAN, 2008

─

With Particular Focus on Those Leaving Japan in the Middle of Treatment

─

The International Exchanging Committee of the Japanese Society for Tuberculosis

Background

Japanese statistics of tuberculosis (TB) show a steady decline in the incidence of newly identified cases of tuber-culosis. There were 19.4 new cases per 100,000 population in 2008 and it was the first year showed the rate dropped below 20 per 100,000 population. Nevertheless, it is still higher prevalence rate compared to that of other developed countries, with over 24,000 new patients developing TB disease every year, and Japan is still considered as a moderate prevalence nation1).

The proportion of foreign residents with TB among all patients in Japan has been rising steadily and its number reached to 945 in 2008. Nearly 60% of foreigners with TB were from China, South Korea and the Philippines. Total of 70% of these cases were concentrated in the 20_39 age bracket. An analysis of therapeutic results for the cohort of new cases registered in 2007 showed many patients were transferred out withdrawing treatment, with some patients choosing to drop out or discontinue treatment in order to return home.

As the foreign population in Japan is expected to in-crease in the future, it is inevitable that many foreigners enter from countries with a high prevalence of TB. We conducted a national survey with the aims of elucidating the problems that compel foreign residents to return to their home country partway through treatment, and social backgrounds in foreign-ers with TB returning home before completion of treatment. We also analyzed demographic difference and risk factors in foreign resident patient groups who underwent successful treatment, discontinued treatment and returned to their home country.

Methodology

Questionnaires were distributed to 530 public health centers throughout Japan. Respondents were asked to fill in and return the questionnaires regarding foreign patients with TB regis-tered between January 1 to December 31, 2008. Responses were entered into a database created using Microsoft Access 2003. Statistical analyses were performed using Minitab14. This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Nagasaki University Hospital (approval number 10022578).

Survey structure

1. Number of registered foreign TB cases ─ all eligible facil-ities nationwide

2. Patient information─ for eligible facilities with registered foreign TB patients 1) Facility-specific ID of patients 2) Gender 3) Age 4) Nationality 5) Residency status 6) Occupation

7) Health insurance cover 8) Drug susceptibility of isolates 9) Treatment outcome

10) Patient returning home during treatment (yes/no) If yes to Q11:

11) Reason(s) for returning home

12) Attempts to encourage the patient to remain in Japan for treatment

13) Adequacy of information provided to patient 14) Treatment strategy after the patient returns home 15) Tracing the treatment outcome in home country All respondents:

16) Problems/issues in the management of foreigners with TB 17) Comments regarding the management of foreigners with

TB

Privacy policy

This epidemiological study involves retrospective analysis of data on foreign residents in Japan who were diagnosed and registered as patients with TB. Personal information such as name, initials, address or date of birth─ is not included in the study. Accordingly, provisions in relation to the collection of personal information are not considered applicable. The researchers have exercised due care in information collection and handling. Data held on computers is subject to ID and password protection, and is accessible only by the researchers. Data processing is performed in research rooms that can only be physically accessed by authorized personnel.

China (242) (No. of patients) South Korea (71) Philippines (237) Indonesia (46) Brazil (39) Vietnam (33) Thailand (26) Peru (22) Nepal (20) India (20) Mongolia (12) Africa (9) Myanmar (6) Others (47)

Fig. 1 Nationality distribution of foreign residents

with tuberculosis in Japan

Fig. 4 Category of health insurance of foreign residents

with tuberculosis in Japan

Fig. 2 Age distribution of foreign residents with

tuberculosis in Japan

Fig. 3 Residency status of foreign residents with

tuberculosis in Japan

Fig. 6 Among foreigners with tuberculosis living in Japan,

those who returned (or did not return) to home country mid-way through their treatment

500 400 300 200 100 0 6 31 409 217 105 34 30 0 _ 9 10 _ 19 20 _ 29 30 _ 39 40 _ 49 50 _ 59 60 _ Age No. of patients Permanent and long-term resident (227)

Residency for less than three years (293)

Illegal resident/ stayer (34)

Landed temporarily (landed at the port of call) (3) Others (22) Residency for three years or more (143) Unclear (97) (No. of patients)

Unclear if they returned to home country or relocated within Japan (19) Others (14) No (649) Yes (144)

*“Yes” and “Others” include some patients who temporarily returned

to their home country. (No. of patients) Fig. 5 Treatment outcomes of foreign residents

with tuberculosis in Japan Treatment exceeding 12 months (26) Unable to judge (25) Completed treatment 449 Cured(115) Died (17) Failed (5) Dropped out(29) Moved out (in Japan) (44)

Moved out (returned to home country) (116) (No. of patients) Others (82) Private expense (116) Employees’ insurance (264) (No. of patients) National Health Insurance (366)

account when considering the conclusions of the study. ・Nationality and age

Figs. 1 and 2 show the distribution of nationality and age of the foreign patients, respectively. Note the consistency with the study published in Kekkaku Vol. 84, No. 11 : 743_746 (2009). In both studies, China, the Philippines and South Korea account for around 60% of foreigners with TB in Japan, with much of the remaining 40% were also from the Asian region. Similarly, most cases (around 70%) are concentrated in the 20_39 age bracket, which is markedly younger than that of the native Japanese population.

・Residency status and health insurance

The most common residency status among foreigners with

Results

Questionnaires were sent to 530 public health centers throughout Japan. Responses were received from 449 facil-ities, for a response rate of 84.7%. Foreign residents with TB were diagnosed in 243 facilities (54.1%). There were 834 reports between January and December, 2008. A total of 44 patients were transferred to another domestic facility and 57 patients were transferred from another domestic facility; for the purpose of simplification, however, transferred cases have been incorporated in the total and are not analyzed separately. The potential influence of transfers should be taken into

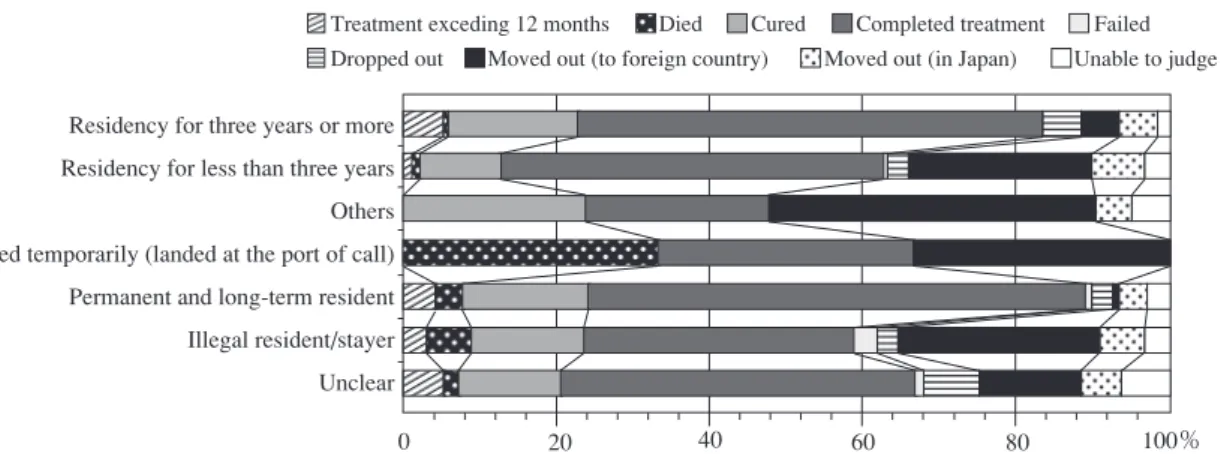

Fig. 7 Relationship between the residency status and treatment outcome of foreign residents with tuberculosis in Japan

Fig. 8 Relationship between category of insurance and treatment outcomes of foreign residents with tuberculosis in Japan

0 20 40 60 80 100%

Residency for three years or more Residency for less than three years Others Landed temporarily (landed at the port of call) Permanent and long-term resident Illegal resident/stayer Unclear

Treatment exceding 12 months Died Cured Completed treatment Failed Dropped out Moved out (to foreign country) Moved out (in Japan) Unable to judge

0 20 40 60 80 100%

Others National Health Insurance Private expense Employees’insurance

Treatment exceding 12 months Died Cured Completed treatment Failed Dropped out Moved out (to foreign country) Moved out (in Japan) Unable to judge

TB was residency for less than three years (293 patients, 35.8 %), followed by both permanent and long-term residents (227, 27.7%), and residency for three years or more (143, 17.5%) (Fig. 3). There were 34 illegal residents (4.2%). As Fig. 4 indicates the majority of patients (630, 76.1%) had health insurance, either under the National Health or through an employee health insurance scheme, while 116 (14.0%) paid their health expenses directly.

・Treatment outcome and number of patients returning home (including partway through treatment)

As shown in Fig. 5, 116 of the 826 reported cases (14%) discontinued treatment in order to leave Japan (normally to return their origin). This number swells to 144 (17.4%) if patients who returned home temporarily during treatment are also included (see Fig. 6).

・Influence of residency status and health insurance cover on likelihood of returning home midway through treatment Fig. 7 illustrates how foreigners with less permanency in Japan were more likely to return home during treatment. Seventy-one of 292 foreigners with residency of less than three years (24.3%) and nine of the 34 illegal residents (26.5%) returned home, compared to just seven of 141 with residency for three or more years (5.0%) and two of 223 permanent and long-term residents (1.0%). Those with health insurance were more likely to remain in Japan (Fig. 8). Only 19 of 361 patients with National Health Insurance (5.3%), and 40 of 263 patients with employee insurance (15.2%) returned home country,

whereas 39 of 116 patients with no health insurance (33.6%) returned home country.

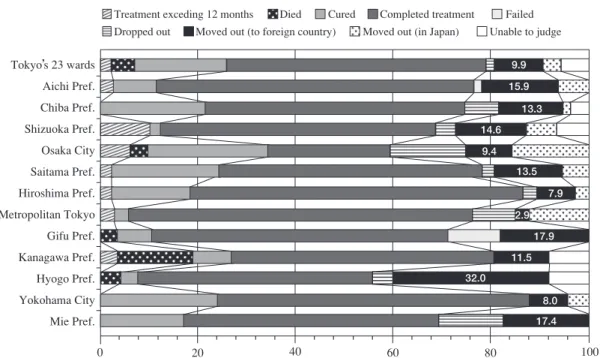

・Influence of location on likelihood of returning home mid-way through treatment

Figs. 9 and 10 illustrate the extent of regional variation of cases of foreigners returning home during treatment for TB, broken down by prefecture and major city. Residents of the Tokyo metropolitan area were more likely to complete treat-ment, whereas those in regional areas were more likely to return home country. Only 2.9% of residents in Metropolitan Tokyo returned home country during treatment (also Tokyo’s 23 wards=9.9%, Yokohama=8.0%, Kawasaki=9.1% and Osaka=9.4%) compared to 50% of patients resident in Ibaraki Prefecture, 40% in Shiga Prefecture, 32% in Hyogo Prefecture and 31% in Kumamoto Prefecture.

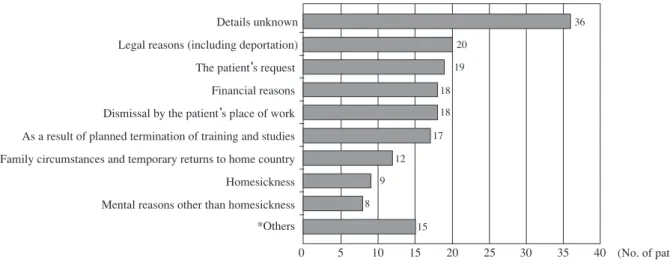

・Reasons for returning home country

Fig. 11 shows the breakdown of reasons for leaving Japan. A significant number of respondents (36 respondents) did not provide an explanation. It is possible that some of these may have had to return home country with unexpected reasons. Where an explanation was provided, the most common reason was forced repatriation or other legal requirement (20 respond-ents), whereas other reasons were personal circumstances, economic necessity, cessation of employment, and the comple-tion of studies or training (17_19 respondents for each reason). ・Encouraging patients to complete treatment in Japan/pro-viding health advice on treatment outside of Japan

Fig. 10 Treatment outcomes of foreign residents with tuberculosis in Japan by prefecture and by

ordinance-designated city (prefectures and cities that have from 10 to 19 patients)

0 20 40 60 80 100%

Osaka Pref. (excl. Osaka City) Nagano Pref. Gunma Pref. Fukuoka Pref. Fukuoka City Kumamoto Pref. Okayama Pref. Niigata Pref. Ibaraki Pref. Nagasaki Pref. Kawasaki City Shiga Pref. Fukushima Pref. 18.8 12.5 15.4 30.8 16.7 15.4 50.0 9.1 40.0 30.0

Treatment exceding 12 months Died Cured Completed treatment Failed Dropped out Moved out (to foreign country) Moved out (in Japan) Unable to judge Fig. 9 Treatment outcomes of foreign residents with tuberculosis in Japan by prefecture and by

ordinance-designated city (prefectures and cities that have more than 20 patients)

0 20 40 60 80 100% 15.9 9.9 13.3 14.6 9.4 13.5 7.9 2.9 17.9 11.5 32.0 8.0 17.4 Tokyo’s 23 wards Aichi Pref. Chiba Pref. Shizuoka Pref. Osaka City Saitama Pref. Hiroshima Pref. Metropolitan Tokyo Gifu Pref. Kanagawa Pref. Hyogo Pref. Yokohama City Mie Pref.

Treatment exceding 12 months Died Cured Completed treatment Failed Dropped out Moved out (to foreign country) Moved out (in Japan) Unable to judge

In most cases, patients who returned home countries during treatment, or even before commencing treatment, had not been encouraged to remain in Japan to complete their treatment. Fig. 12 shows, only 51 facilities (34.5%) reported that they strongly encouraged or encouraged patients to complete their treatment in Japan. Meanwhile, the majority of facilities were able to provide either considerable or some health advice to patients who returned home country during treatment (see Fig. 13).

・Follow-up on patients leaving Japan

Fig. 14 shows the approach taken by the treating facilities to patients who returned home country partway through treatment. In most cases (44), patients were given a referral letter and advised to see their local doctor (the patient was responsible for locating a suitable doctor). The response of the facility is unknown in 24 cases. A further 22 patients were issued medication for their remaining time in Japan (considered sufficient to complete the treatment) and advised to contact

Fig. 12 Whether or not the public health center recommended

the patient to stay until the treatment completed (including temporary returns)

Fig. 13 Was educating the patients possible in case they

returned home mid-way through treatment? (including temporary returns) We did not especially recommend it (60) (No. of patients) We recommended it to a certain extent (35) We strongly recommended it (16)

Returned home suddenly or without us knowing about it (7)

We encouraged the patient to return home (5)

The patient could not be contacted (2)

The patient returned home before starting treatment or receiving diagnosis (3) Others (20) (No. of patients) Possible, to a certain extent (63)

Can’t say either way (19)

Not very possible (20)

Totally impossible (11)

Fully possible

(34)

Fig. 11 Reasons for returning to home country mid-way through treatment (multiple answers)

(including temporary returns to home country) Details unknown Legal reasons (including deportation) The patient’s request

Financial reasons Dismissal by the patient’s place of work As a result of planned termination of training and studies Family circumstances and temporary returns to home country Homesickness Mental reasons other than homesickness *Others 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 36 20 19 18 18 17 12 9 8 15 (No. of patients)

Fig. 14 Subsequent therapeutic policies in case patients returned home mid-way through treatment 44 24 22 18 18 9 6 4 3 3 2 0 10 20 30 40 50(No. of patients)

・ I investigated local medical institutions (or public health centers) by myself, contacted them directly, then referred them to the patient ・Doctor or I handed out a letter of referral to the patient, and encouraged him/her to visit a nearby doctor (have the patient decide which doctor to go to, after returning home) ・Unclear ・Doctor or I planned to end the treatment by handing out prescriptions to cover the remaining several months of treatment in Japan ・Doctor or I only encouraged them to visit a nearby doctor after returning home (no letters of referral in particular) ・Doctor or I handed a letter of referral and prescriptions (have the patient decide which medical institution to go to, after returning home) ・Doctor or I prescribed medicines to cover the period of the patient’s temporary return to home country

・Others ・Doctor or I consulted with the Research Institute of Tuberculosis, contacted the hospital they referred me to, then handed out a letter of referral to the patient ・Doctor or I investigated local medical institutions by himself or myself, and had the patient bring a letter of referral addressed to the medical institutions ・Doctor or I consulted other institutions (NPOs, government offices, etc.), and contacted medical institutions that were referred to me

*Others : I’ll go home since I came here for sightseeing only.

Recommendations and complaints from the place where I undergo training at. My contract says that I’ll return to my home country if I get sick.

Table Problems and other matters seen in dealing with foreign tuberculosis patients

・

・ The problems of self-pay burdens of government-subsidized treatment and medical expenses (including transportation costs) (Article 37-2 of the Infectious Diseases Control Law)

・

・ Less understanding and less cooperation of the employer ・

・ Problems caused by a misunderstanding between the public health center and a Japanese man who was the key person ・

・ They fail to come on the dates of appointment, and make repeated cancellations ・

・ Since they replace cellphones quickly, it’s difficult to reach them; they do not come on the dates of appointment ・

・ We had trouble communicating with the immigration office ・

・ Financial problems ・

・ The patient was a domestic violence victim, so she was sent to a shelter, but ended up returning to her husband ・

・ The patient lives with another trainee, so it’s difficult to secure a place for him/her to live alone ・

・ Making him/her understand the differences in treatment methods from his/her native country ・

・ Coping with a lack of fixed address after treatment completion (follow-up with tuberculosis check-ups) ・

・ Since we carried out a contact medical checkup at the workplace, the disease name was revealed, and the patient was fired. ・

・ Difficulty in reaching and contacting the patient ・

・ The patient was diagnosed with smear positive 3+ during the early stage of her pregnancy. Since she was a foreign national and was in the early stage of pregnancy, it took time finding a medical institution.

・

・ The patient did not readily understand, and agree to, our recommendation to be hospitalized ・

・ We had a tough time since the patient’s husband, who was the key person, was difficult to deal with ・

・ Even if we could identify persons whom the patient had contacted, we cannot get hold of them ・

・ The patient also had HIV ・

・ The patient was being imprisoned in jail, so we could not grasp the details ・

・ If the patient is a non-official resident, should we report him/her to the immigration office or not? ・

・ There are no key persons

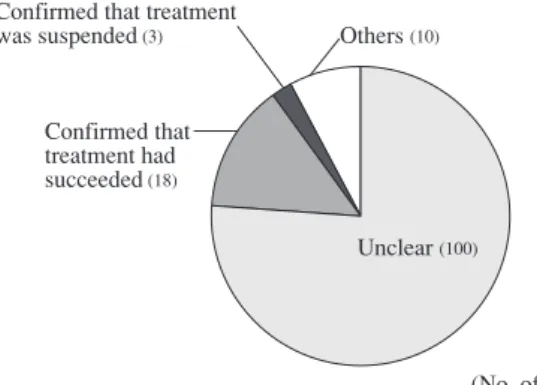

Fig. 15 Grasping of the subsequent course in case

patients returned home mid-way through treatment Unclear (100)

(No. of patients) Others (10)

Confirmed that treatment was suspended (3)

Confirmed that treatment had succeeded (18)

Fig. 16 Difficulties in dealing with foreign tuberculosis patients living in Japan (multiple answers accepted)

Language and communication Cultural differences The problem of cost until a diagnosis is made Cannot grasp their history of past illnesses Don’t know which medical institutions to refer to after they return home

Cannot identify the address of the patient himself/herself Cannot identify people whom the patient had contacted Differences in meal habits Legal problems Others 0 100 200 300 400 500 486 100 103 71 69 64 64 53 25 23 (No. of patients) their local doctor in their home country, but without receiving a referral letter (18 cases). In four cases, the facility attempted to line up a suitable treatment facility in the patient’s home country through the Research Institute of Tuberculosis. ・Success of treatment after leaving Japan

As shown in Fig. 15, the final outcome was unknown in most cases. Successful treatment was confirmed in only 18 cases (13.7%).

・Key issues in treatment of foreign TB patients

Language and cultural differences were overwhelmingly the main difficulties experienced by respondents, as illustrated in Fig. 16. Other issues cited were expenses leading up to the diagnosis, and difficulty grasping details of each individual case. Table lists further issues identified in the survey.

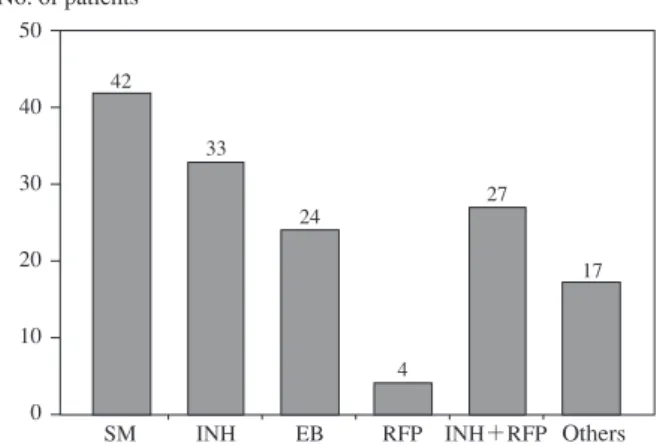

Fig. 17 Status of drug resistance of registered foreign

tuber-culosis patients living in Japan (87 patients who answered that they had drug resistance; some had resistance to more than two drugs)

Fig. 18 Status of drug resistance of 144 foreign

tubercu-losis patients who returned home mid-way through treatment (including temporary returns) (22 patients had some sort of drug resistance; some had resistance to more than two drugs.)

50 40 30 20 10 0 42 33 24 4 27 17

SM INH EB RFP INH+RFP Others

No. of patients 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 12 7 4 2 11 3 SM EB INH RFP INH+RFP No. of patients Others

SM: streptomycin INH: isoniazid EB: ethambutol RFP: rifampicin ・Drug susceptibility of isolates

Participating public health centers were asked to make an estimate of drug susceptibility result based on the available information. Responses were received from 87 cases. As Fig. 17 shows, 27 cases were reported as exhibiting multiple drug-resistance. Of these, 11 returned home country during treatment. Including these cases, drug resistance was identified in 22 of 144 patients who returned home during treatment (see Fig. 18).

Discussion and strategies for achieving successful treatment

The results of this study indicate that TB in foreigners resident in Japan tends to be more prevalent in young adults, and among those from Asia (particularly China, South Korea and the Philippines). These findings are consistent with statistical data1) and previous academic studies2)_4). This

study found that 14% of foreigners return to home country, a result almost identical to the findings of another study (Okada et al.). This figure rises to 17% if we include patients who return home temporarily for any reason during the treatment period. With respect to residency status and health insurance cover, the current study found that short-stay foreigners and illegal residents, as well as those without health insurance cover, were more likely to return to home country before com-pleting the treatment regimen. Again, this is consistent with the findings of previous reports3) 5).

This study analyzed responses from health center officers directly engaged in TB program, with particular reference to patients who had returned to home. The questionnaire focused on reasons why patients chose to leave Japan, the advice and/or assistance provided by the facility, the ability of the facility to trace the patients’ outcome after returning to home country, and the difficulties the officers encountered. A key issue was the inability of facilities to issue referral letters to appropriate

medical facilities in their home countries due to a lack of information of situation of TB treatment in other countries. Respondents reported many instances of patients departing with no warning or explanation. As expected, there were many cases where treatment was discontinued by patients having to return home for legal or economic reasons.

There was also a significant discrepancy between urban and regional residents in terms of the decision of returning to origins. Residents of the Tokyo metropolitan area were more likely to remain in Japan and complete their treatment, while those in the countryside were more likely to return home midway through treatment. It has been reported6) 7) that in the

areas with large foreign populations, foreigners who contract TB are now more likely to remain in Japan to complete their treatment due to the success of concerted campaigns by local governments, health centers, medical institutions and NGOs, as well as greater knowledge in this area. The potential via-bility of producing a guidebook on treating TB in foreign patients and introducing medical TB checkups at Japanese language schools has also been investigated4). There is no

doubt that initiatives to encourage completion of treatment are very much in the hands of prefectural and local government and health centers. This is illustrated by some of the key issues identified in our study: the duty of confidentiality in relation to the immigration department; difficulty accessing interpreting services at the local government level due to restrictions on time and availability; and insensitivity of local employers towards employees in need of treatment.

There is increasing support around the world for TB treatment in general and the directly observed treatment, short-course (DOTS) strategy in particular. However, TB treatment and management program can vary considerably between countries, and even between regions within a country due to political considerations. Some areas are not adequately equipped to deal with TB, and have only a limited number

of hospitals and institutions capable of managing multi drug-resistant TB. Given that foreigners with TB in Japan are more likely to present with multi-drug resistant TB, the first priority should be to convince them to remain in Japan through to the end of the treatment regimen.

To this end, treating physicians should opt for a six-month treatment course, and where necessary negotiate with the immigration department to have the patient’s period of stay extended to ensure that treatment can be completed. In cases where notifying the immigration department of a suspected violation of the immigration laws, as required by law, would compromise the treatment regimen to the significant detriment of the patient, our priority should be to maintain patient confidentiality8).

In cases where returning home partway through treatment is unavoidable, the patient should normally be issued with medication to cover the remaining treatment period. In cases where the patient is obliged to leave Japan for economic or legal reasons or because of an unsympathetic employer, the treating facility should attempt to ensure continuity of treat-ment by forwarding the relevant patient detailed information to an appropriate medical institution in the patient’s home country. The Department of Programme Support at the Re-search Institute of Tuberculosis (RIT) has already identified a number of reliable institutions in China, South Korea, the Philippines, Cambodia and Nepal, with whom patients can make a consultation. In addition, RIT has an extensive network of TB facilities in countries around the world, and is ready to arrange introductions and referrals for patients requiring ongoing treatment. Seeking the cooperation from them is also recommended to achieve the best outcomes for your patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the public health centers around Japan who generously contributed their time to this study. We also wish to acknowledge Dr. Hitoshi Hoshino,

formerly of the Department of Programme Support at the Research Institute of Tuberculosis, for his advice and support and doctors and staff at the Research Institute of Tuberculosis. Finally, we wish to thank Dr. Misuzu Tsukamoto, who con-ducted this study.

References

1 ) Tuberculosis Annual 2008 Series: Incidence of Tuberculosis among Foreigners (in Japanese). Tuberculosis Surveillance Center, the Research Institute of Tuberculosis, Japan Anti-Tuberculosis Association (JATA), released 2010.

2 ) Toyoda E, Otani T, Suzuki T, et al.: Study of Tuberculosis Patients in Japan (in Japanese). Kekkaku. 1991 ; 66 : 805 _ 810.

3 ) Yoshiyama T, Ishikawa N, Hoshino N, et al.: Recent epide-miological trends among foreign residents in Japan with tuberculosis (in Japanese). Kekkaku. 1999 ; 74 : 667_675. 4 ) Okada M, Toyoda E, Shimouchi A, et al.: Strategies and

controls to combat the imported infectious disease of multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis (in Japanese) (funded by 2008_ 2010 MHLW grant), 2010.

5 ) Yamagishi F, Suzuki K, Sasaki Y, et al.: Background to instances of pulmonary tuberculosis among foreign residents in Japan and ability to complete of treatment (in Japanese). Kekkaku. 1993 ; 68 : 545_550.

6 ) Suzuki M, Hojo M, Kobayashi N, et al.: Clinical analysis on tuberculosis cases among foreigners in our hospital (in Japanese). Kekkaku. 2008 ; 83 : 661_666.

7 ) Ishikawa N: Foreigners with tuberculosis ─ background and strategies (in Japanese). Kekkaku. 1995 ; 70 : 691_703. 8 ) The 2010 revised edition of the Handbook for Medical

Consultants on Treatment of HIV Positive Foreign Nationals developed by the Research Group on Specific HIV Prevention Strategies and Intervention Outcomes (in Japanese), an AIDS projected funded under the FY2009 MHLW (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare) Grants System.

The International Exchanging Committee of the Japanese Society for Tuberculosis Chairperson: Junichi KADOTA

Former chairperson: Shigeru KOHNO

Members: Ryoichi AMITANI, Naoto KEICHO, Hiroyasu TAKEYAMA, Naohiko CHONABAYASHI, Mitsuo HASE, Toshio HATTORI,