Extensive reading and the motivation to read : A pilot study

著者(英) Matthew T. Apple

journal or

publication title

Doshisha Studies in Language and Culture

volume 8

number 1

page range 193‑212

year 2005‑08‑25

権利(英) Doshisha Society for the Study of Language and Culture

URL http://doi.org/10.14988/pa.2017.0000007598

Extensive reading and the motivation to read:

A pilot study

Matthew T. APPLE

Keywords:Motivation, extensive reading, learner beliefs

Abstract

At the beginning of the spring 2004 academic semester 85 Japanese university learners were surveyed in a pilot study about their attitudes and motivation to read and study both Japanese and English. Results of the first questionnaire were analyzed into the four factors instrumental orientation, attitudes toward L1 reading, interest in L2 language and culture, and language learning beliefs. After three months of an extensive reading (ER) program, student took the same questionnaire to determine whether ER had affected their motivation. The results showed virtually no difference between factor scores for the pre and post-ER questionnaire items.

Implications and future directions for a larger-scale study based on the pilot are discussed.

Introduction

In Gardner’s socio-educational theory of language learning, integrative motivation comprises the three components of integrative orientation, attitudes toward the target language group, and interest in learning foreign

193

Doshisha Studies in Language and Culture, 8(1), 2005: 193 – 212.

Doshisha Society for the Study of Language and Culture,

© Matthew T. APPLE

languages in general (Gardner & Lambert, 1972; Gardner, 1985; Gardner, Day, & MacIntyre, 1992; Gardner & MacIntyre, 1993). The integrative- instrumental dichotomy of the socio-educational theory continues to hold sway over second language (L2) motivation research, despite a host of other theories. The most influential of the alternative theories to Gardner’s model, Deci and Ryan’s (1985) self-determination theory, popularized the terms intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in the field of second language acquisition (SLA).

However, motivational theories known collectively as expectancy-value theories have been well known to psychologists for over thirty years.

Expectancy-value theories largely stem from Atkinson and Birch’s (1974) achievement motivation theory, which claimed that behavior was determined by the expectance of success, the value of incentive, the need for achievement, and the fear of failure. Other expectancy-value theories such as attribution theory, self-efficacy theory and self-worth theory have used and added to components from Atkinson and Birch.

Each of these theories (and many more not listed; see Dornyei, 2001, for detailed descriptions of alternative approaches to Gardner’s socio- educational model) approaches the psychological concept of motivation from a slightly different, and valuable, point of view. Dornyei (2003) has highlighted the increasing importance of task motivation in language teaching to reflect the activities in the actual classroom. He proposes a “task processing system” comprised of the three components task execution, appraisal, and action control to explain how learners continuously negotiate and regulate their motivation to do certain tasks. (Dornyei, 2003, p. 16).

Motivational research in SLA usually covers a broadly defined domain, that of the learner’s motivation to study the second language in general. The present research concerns itself with a much more narrowly defined issue–the motivation to read in one’s L2. Recently there has been an increased interest in extensive reading (ER)–reading large amounts of

194

relatively easy text, usually outside the formal classroom setting–as a method of promoting reader fluency, vocabulary acquisition, and good reading habits. However, there have been few studies, summarized below, which have examined the relationship between ER and the motivation to read. The present pilot study represents a further attempt to investigate this relationship and proposes that the more conventional expectancy-value or self-determination theory-based perspectives do not adequately explain learner motivation to read in an English as a Foreign Language (EFL) context.

Extensive reading (ER) and motivation

ER has been positively correlated to learner gains in listening, grammar knowledge, word recognition, reading scores on standardized exams, written performance, and oral production (Elley & Mangubhai 1983; Hafiz

& Tudor, 1989; Mason & Krashen, 1997a; 1997b; Walker, 1997; Hayashi, 1999; Day & Bamford, 2000; Renandya & Jacobs, 2002). Although ER has also been promoted as a method of increasing reading motivation, relatively few studies have examined the relationship between motivation and reading in a second language. Some studies have given anecdotal evidence of increased L2 reading motivation (Mason & Krashen, 1997a; Sheu, 2003), while others have investigated the relationship between affect and L1 and L2 reading (Camiciottoli, 2001; Yamashita, 2004). Thus far, none has demonstrated measurable motivational improvements due to using graded readers for extensive reading.

To explain reading motivation for native language speakers, Wigfield (1997) proposed three components: competency and efficacy beliefs, achievement values and goals, and social aspects. Mori (1999, 2001, 2002, 2004) has examined the application of Wigfield’s components in studies of L2 reading motivation in a Japanese EFL context. Relying primarily on expectancy-value theories of motivation, Mori’s research (2002) indicated

195

four components which she labeled intrinsic value of reading in English, attainment value of reading in English, extrinsic utility value of reading in English, and expectancy for success in reading in English. Similarly, Takase (2001) examined learner motivation to read graded readers in a yearlong ER program for 64 Japanese high school students. She concluded that the most important factors for motivating students to read no ital.

positive intrinsic factor in reading English, parents’ and family attitudes in reading in Japanese, and ital.

In all these studies, the questionnaires were administered only once during the research period. The present paper represents the second stage of a two-stage project to examine whether ER can help improve learner motivation to read English as a second language by correlating two questionnaires, one before and one after student participation in an ER program. In the first stage, 330 Japanese university students were surveyed to establish their initial attitudes and motivation toward reading in their native language and in English (Apple, 2005b; 2005d); however, the second stage was limited to 85 students in the pre-task questionnaire and 74 in the post-task questionnaire due to a variety of classroom environment reasons.

Background: The Communicative English program

Students in this study were studying English, Japanese, or International Studies in the Faculty of Foreign Languages of a private four-year university in western Japan. Based on scores from a TOEIC exam given at the end of each semester students were divided into six different levels in a required 2-year Communicative English (CE) program. Each level was comprised of 2 to 4 classrooms each, and at least four classes include repeater students, in addition to two classes composed entirely of repeater students. Many repeaters were third and fourth year students who still had not completed the two-year program. The motivation for many students in the CE program, especially those in the lower levels, was perceived as

196

extremely low. In an attempt to increase reading motivation the directors of the CE program decided at the beginning of the 2004 academic year to begin an extensive reading program, which would account for 10 percent of the class grade.

During the first semester of the program, students handed in a “weekly reading log” detailing the dates and number of pages read (logs were based on Apple, 2005b, and Ono, Day, & Harsch, in press; see Appendix A for an example), and upon finishing a book, students handed in a “reader response” report. As recommended by Day & Bamford (2000), the reports were not graded or corrected for errors, but simply stamped as accepted and returned to the student with encouraging comments (see Appendix B and C). Students failing to reach the 300 page requirement received an appropriate percentage of the 10% overall grade, whereas those who exceeded the requirement received extra credit (for other accounts of ER programs, see Helgesen, 1997; Hill, 1997; Lemmer, 2004).

Methodology and research design

The extensive reading questionnaire about English and Japanese reading motivation and attitudes toward learning was written in English and translated into Japanese. The Japanese version was cross-checked by two native Japanese speakers; after minor corrections were made to resolve possible vague interpretations of one or two items, the questionnaire was distributed to instructors to be individually administered at the beginning of the first week of the 2004 spring semester. The questionnaire was based on sections of Gardner’s (1985) Attitude/Motivation Test Battery (AMTB), which consisted of 130 items. For this study, the number of items was drastically reduced to 25 Likert questions (6 scale, with no “undecided” or

“neither” option), partly due to time restraints for class implementation and partly due to concerns that students would leave several items of a larger questionnaire unanswered.

197

The questionnaire was implemented twice, once during the first week of classes in the spring semester in April 2004 and once again at the end of classes in July 2004. Questionnaires were administered during regular class time by individual instructors in Level 3 through Level 6 classes of the CE program. For the pre-ER treatment, N was 85; for the post, N=74.

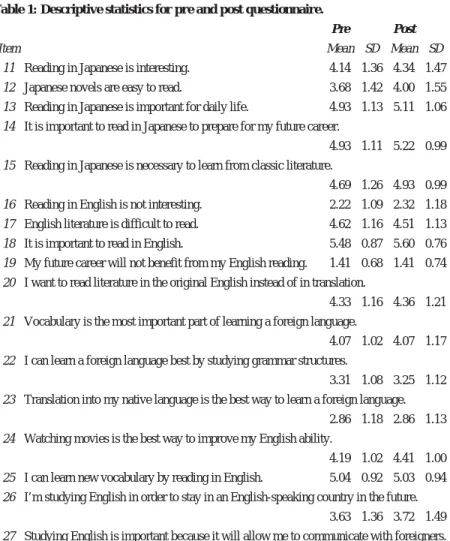

Descriptive statistics from pre and post are shown below in Table 1.

Table 1: Descriptive statistics for pre and post questionnaire.

Pre Post

Item Mean SD Mean SD

11 Reading in Japanese is interesting. 4.14 1.36 4.34 1.47 12 Japanese novels are easy to read. 3.68 1.42 4.00 1.55 13 Reading in Japanese is important for daily life. 4.93 1.13 5.11 1.06 14 It is important to read in Japanese to prepare for my future career.

4.93 1.11 5.22 0.99 15 Reading in Japanese is necessary to learn from classic literature.

4.69 1.26 4.93 0.99 16 Reading in English is not interesting. 2.22 1.09 2.32 1.18 17 English literature is difficult to read. 4.62 1.16 4.51 1.13 18 It is important to read in English. 5.48 0.87 5.60 0.76 19 My future career will not benefit from my English reading. 1.41 0.68 1.41 0.74 20 I want to read literature in the original English instead of in translation.

4.33 1.16 4.36 1.21 21 Vocabulary is the most important part of learning a foreign language.

4.07 1.02 4.07 1.17 22 I can learn a foreign language best by studying grammar structures.

3.31 1.08 3.25 1.12 23 Translation into my native language is the best way to learn a foreign language.

2.86 1.18 2.86 1.13 24 Watching movies is the best way to improve my English ability.

4.19 1.02 4.41 1.00 25 I can learn new vocabulary by reading in English. 5.04 0.92 5.03 0.94 26 I’m studying English in order to stay in an English-speaking country in the future.

3.63 1.36 3.72 1.49 27 Studying English is important because it will allow me to communicate with foreigners.

198

5.26 1.03 5.46 0.67 28 By studying English I can learn about foreign customs and cultures.

5.02 1.05 5.16 0.92 29 Reading English literature is a good way to learn about other countries.

4.76 1.01 4.72 1.04 30 Studying English is important for my future career. 5.08 0.95 5.19 0.87 31 Others will respect me if I am knowledgeable in English. 3.59 1.28 3.84 1.44 32 It is important to study English in order to get good scores on tests such as the TOEIC

and TOEFL. 4.68 1.17 4.84 0.98

33 Studying English is important because it will make me a more knowledgeable person.

4.54 1.13 4.68 1.25 34 It is important for me to perform better than other students in my class.

3.53 1.13 3.68 1.22 35 Moving to a higher proficiency level in the Communicative English program is one of

my goals in studying English. 4.42 1.32 4.53 1.46

The data for both pre and post extensive reading questionnaire rounds were factor analyzed using principle axis factors and varimax rotation. Five factors were found in both the pre and post questionnaire results. These were tentatively labeled Instrumental orientation, Attitudes toward L1 reading, Interest in L2 language and culture, Language learning beliefs, noital Attitudes toward L2 study. Items did shift slightly between the pre and post factors; however, this was expected, and the first four factors largely remained the same between the two rounds of questionnaires.

Unfortunately, the expected factor of “Attitudes toward L2 study” seemed to completely change items in the post questionnaire. For the purposes of comparing the factors between pre and post, this factor was excluded from further analysis. The remaining four factors are presented in Tables 2 through 5 below.

199

Table 2: Instrumental orientation

Pre-ER program a=.82

33. Studying English is important because it will make me a more knowledgeable person. 0.782 34. It is important for me to perform better than other students in my class. 0.769 31. Others will respect me if I am knowledgeable in English. 0.680 32. It is important to study English in order to get good scores on tests such as the TOEIC and TOEFL. 0.664 35. Moving to a higher proficiency level in the Communicative English program is one of my goals. 0.402

Post-ER program a=.76

34. It is important for me to perform better than other students in my class. 0.670 35. Moving to a higher proficiency level in the Communicative English program is one of my goals. 0.653 33. Studying English is important because it will make me a more knowledgeable person. 0.614 26. I’m studying English in order to stay in an English-speaking country in the future. 0.444 31. Others will respect me if I am knowledgeable in English. 0.443

Table 3: Attitudes toward L1 reading

Pre-ER program a=.86

16. Reading in English is not interesting. 0.805

15. Reading in Japanese is necessary to learn from classic literature. 0.795 14. It is important to read in Japanese to prepare for my future career. 0.780

12. Japanese novels are easy to read. 0.668

13. Reading in Japanese is important for daily life. 0.568

Post-ER program a=.80

14. It is important to read in Japanese to prepare for my future career. 0.790 13. Reading in Japanese is important for daily life. 0.667

12. Japanese novels are easy to read. 0.607

11. Reading in Japanese is interesting. 0.606

15. Reading in Japanese is necessary to learn from classic literature. 0.583

Table 4: Interest in L2 language and culture

Pre-ER program a=.75

29. Reading English literature is a good way to learn about other countries. 0.696 21. Vocabulary is the most important part of learning a foreign language. 0.568 28. By studying English I can learn about foreign customs and cultures. 0.578 25. I can learn new vocabulary by reading in English. 0.448 19. My future career will not benefit from my English reading. 0.426 30. Studying English is important for my future career. 0.396 200

Post-ER program a=.83

27. Studying English is important because it will allow me to communicate with foreigners. 0.734 28. By studying English I can learn about foreign customs and cultures. 0.669 30.Studying English is important for my future career. 0.618 19. My future career will not benefit from my English reading. (neg. loading) 0.615 32. It is important to study English in order to get good scores on tests such as the TOEIC and TOEFL. 0.569 29. Reading English literature is a good way to learn about other countries. 0.482

Table 5: Language learning beliefs

Pre-ER program a=.70

23. Translation into my native language is the best way to learn a foreign language. 0.784 22. I can learn a foreign language best by studying grammar structures. 0.598

Post-ER program a=.74

22. I can learn a foreign language best by studying grammar structures. 0.808 23. Translation into my native language is the best way to learn a foreign language. 0.714 21. Vocabulary is the most important part of learning a foreign language. 0.607

For each factor, item factor scores were computed and the four pre-ER program factors were compared to the same post-ER program factors using a One-Way ANOVA for Repeated Measures. The results showed significance ranging between .819 and .896 (Table 6). In other words, the two rounds of questionnaires showed virtually no change in motivation and attitudes.

Table 6: One-Way ANOVA results (with regressive factor scores)

Pre Post Multi*

Factors Mean SD Mean SD Sig.*

1 Instrumental orientation. .0004 0.94 .0208 0.87 .896

2 Attitudes toward L1 reading -.0235 0.91 -.0030 0.93 .879 3 Interest in L2 language and culture .0083 0.88 -.0265 0.91 .819

4 Language learning beliefs -.0230 0.90 .0088 0.89 .852

*Significance was measured using Pillai’s Trace, Wilk’s Lambda, Hotelling’s Trace, and Roy’s Largest Root. All results were the same.

201

Discussion

An overriding reason that student motivation did not seem to improve may well have been the relatively short time (one academic semester).

Extensive reading may require several months, perhaps even one or two years to increase motivation to read. On the other hand, there are several possibilities to explain why the extensive reading program in this study apparently failed to increase student motivation.

First and foremost, though overall student proficiency as measured by TOEIC score was low (Level 3 class average ranged from TOEIC 345 to 404; Level 6 average was 578 with the highest individual score at 765), student motivation was initially quite high. It is extremely difficult (not to mention unnecessary) to motivate students who are already motivated.

Another reason could be the large number of items relating to studying rather than simply reading English. The kind of reading (novels, magazines, newspapers) was also not specified. Furthermore, the SPSS 11.0 computer program adjusted the participant numbers in order to compare an equal number of factor scores, resulting in N=70 for the One-Way ANOVA. This is barely adequate for such statistical analysis, and the possibility of this small number affecting the outcome cannot be discounted. However, it can be said that the results appear to lean in the direction of no statistically significant improvement in motivation. A future study with larger numbers of participants would be necessary to verify these findings.

The predominance of “instrumental” factors in the results may be due to the fact that extensive reading was required reading, rather than voluntary.

Students had an instrumental reason of 10% of their CE program course grade as incentive to read graded readers. The presence of item 32 (“It is important to study English in order to get good scores on tests such as the TOEIC and TOEFL”) in the pre-ER program instrumental orientation factor may reflect a curriculum requirement: in order for students in this study to

202

qualify for their university’s study abroad program in Australia, students were required to gain a certain score on the TOEIC exam. The existence of this study abroad program may also be reflected in the post-ER program factor, which includes the integratively oriented item 26, “I’m studying English in order to stay in an English-speaking country in the future.”

This mixing of instrumental and integrative appears again in the factor

“Interest in L2 language and culture.” Students are clearly eager to learn about foreign cultures (item 29, “Reading English literature is a good way to learn about other countries”; item 28, “By studying English I can learn about foreign customs and cultures”), but students also perceive the future benefits for their careers (item 19, “My future career will not benefit from my English reading”; item 30, “Studying English is important for my future career.”). Japanese university students in this study may have integrative reasons for studying and reading English, but the reasons can also be construed as instrumental as well.

Conclusions

The results from the current pilot study seem to agree with Mori’s (2002) observation that the integrative-instrumental orientation dichotomy does not seem directly applicable to Japanese students in an EFL context. Mori notes:

In Japan where EFL students have very limited contact with the target language and culture, it can be assumed that their desire to integrate themselves into the target community is rather weak, and consequently cannot be discriminated from other reasons for reading in English. (Mori, 2002, p. 9)

In the past decade, various Japanese researchers writing in both English and Japanese have questioned the validity of the integrative construct in an

203

EFL environment. In summarizing recent articles in Japanese language journals, Irie (2003) pondered the existence in Japanese university students of “mastery orientation,” in which the desire to become proficient in a foreign language is the goal of learning the foreign language. The motivation to learn English becomes a matter of learning for its own sake.

Kimura, Nakata and Okumura (2001) discovered it nearly impossible to separate “instrumental” from “integrative” reasons for studying English no matter the level of education, from junior high school through university. In their study, “instrumental” items such as learning English for the purposes of making friends or traveling abroad “seemed to have a more integrative connotation when taken together with the other questionnaire items” (p. 61) depending upon the factor. The researchers theorized the “lack of a single motivational factor” and the existence of a complicated motivation among Japanese learners for studying English. This seems to concur with Dornyei (1990, 2003) that students in EFL contexts may identify with the L2 while not wanting to “integrate” in the L2 culture.

Recently, Yashima (2002, 2004) has proposed a new orientation called

“international posture.” In contrast to Gardner’s integrative orientation, Yashima’s term refers to learner interests in foreign matters, the willingness and readiness to engage members of the L2 community, but not necessarily wanting to “integrate” or become assimilated into the L2 culture. This concept seems particularly appropriate in English as a foreign language learning contexts such as Japan, where learners have little or no opportunities to contact L2 native speakers. It may be that in the present study, an international or “friendship” orientation (Clement & Kruidenier, 1983) may be a salient feature of Japanese university student motivation to read English. If such an “orientation” exists, it may exist at a level beneath motivation, at the level of learner beliefs, attitudes, and learner styles.

The varying levels of proficiency of study participants (from TOEIC 285 to 765) may have also led to varying degrees of motivation. Lau and Chan

204

(2003) argue that low proficiency students have lower intrinsic motivation and higher extrinsic motivation, if they are motivated at all. The present study did not separate questionnaire results according to either proficiency level or year at university. It is possible that the factors would become more distinct if the results were refined along these lines.

The questionnaire further contained possibly inappropriate items relating to English language study in general. Items concerning reading attitudes toward Japanese (the students’ L1) contributed little to understanding student motivation to read. Future inclusion of items that address specific task motivation to read English may improve delineation of the factors.

Future directions

A relatively small (N=74) number of learners completed both pre and post questionnaires in this pilot study in a single four-month semester.

Therefore, the project will be implemented again in the 2005 academic year in order to include all 400-plus students in the CE program over the course of the entire academic year. As motivation can change over time, validity of the survey could be greatly improved by administering the questionnaire at different times during the academic year. Adding personal interviews with select students at each proficiency level to examine patterns in their reading beliefs could also offer a valuable qualitative perspective (Ushioda, 2001).

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to all instructors and students of the CE program, Dr. David Beglar of Temple University Japan, and two anonymous reviewers of this paper for their helpful comments on an earlier draft.

205

References:

Apple, M. (2005d). Extensive reading and the motivation to read: A preliminary study.

In T. Matikainen (Ed.), The Proceedings of the Seventh Temple University Japan Applied Linguistics Colloquium.

Apple, M. (2005b). Introducing extensive reading: Motivation to read and attitudes toward reading. The Journal of the Faculty of Foreign Languages Himeji Dokkyo University, 17, 61-82.

Atkinson, J.W. & Birch, D. (1974). The dynamics of achievement-oriented activity. In Atkinson, J.W. & Raynor, J.O. (Eds.), Motivation and achievement (pp. 271-325).

Washington, D.C.: Winston & Sons.

Camiciottoli, B. (2001). Extensive reading in English: Habits and attitudes of a group of Italian university EFL students. Journal of Research in Reading, 24 (2), 135-153.

Clement, R. & Kruidenier, B. (1983). Orientations on second language acquisition: 1.

The effects of ethnicity, milieu and their target language on their emergence.

Language Learning, 33, 273-291.

Day, R. & Bamford, J. (1998). Extensive reading in the second language classroom.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Day, R & Bamford, J. (2000). Reaching reluctant readers. English Teaching Forum, 38 (3). 12-17.

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determinism in human behavior. Plenum: New York.

Dornyei, Z. (1990). Conceptualizing motivation in foreign language learning.

Language Learning, 40, 46-78.

Dornyei, Z. (2001). Teaching and researching motivation. Harlow, England:

Longman.

Dornyei, Z. (2003). Attitudes, orientations, and motivations in language learning:

Advances in theory, research, and applications. In Dornyei, Z. (Ed.), Attitudes, orientations, and motivations in language learning: Advances in theory, research, and applications (pp. 3-32).Oxford: Blackwell.

Gardner, R.C. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning: The role of attitudes and motivation. London: Edwin Arnold.

Gardner, R.C., Day, B., & MacIntyre, P. (1992). Integrative motivation, induced anxiety, and language learning in a controlled environment. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 14, 197-214.

206

Gardner, R.C. & Lambert, W.E. (1972). Attitudes and motivation in second language learning. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Gardner, R.C. & MacIntyre, P. (1993). A student’s contribution to second language learning. Part II: Affective variable. Language Teaching, 26, 218-233.

Hafiz, F. & Tudor, I. (1989). Extensive reading and the development of language skills. ELT Journal, 43 (1), 4-13.

Hayashi, K. (1999). Reading strategies and extensive reading in EFL classes. RELC Journal, 30 (2), 114-132.

Helgesen, M. (1997). What one extensive reading program looks like. The Language Teacher, 21 (5), 31-33.

Hill, D. (1997). Setting up an extensive reading programme: Practical tips. The Language Teacher, 21 (5), 91-102.

Irie, K. (2003). What do we know about the language learning motivation of university students in Japan? Some patterns in survey studies. JALT Journal, 25 (1), 86-100.

Kimura, Y, Nakata, Y, & Okumura, T. (2001). Language learning motivation of EFL learners in Japan–A cross-sectional analysis of various learning milieus. JALT Journal, 23 (1), 47-68.

Lau, K. & Chan, D. (2003). Reading strategy use and motivation among Chinese good and poor readers in Hong Kong. Journal of Research in Reading, 26 (2), 177-190.

Lemmer, R. (2004). A brief look at one extensive reading program. On Cue, 12 (2), 24-26.

Mangubhai, F. & Elley W. (1983). The impact of a book flood in Fiji primary schools.

Wellington: New Zealand Council for Educational Research and the Institute of Education, University of South Pacific.

Mason, B. & Krashen, S. (1997a). Can extensive reading help unmotivated students of EFL improve? ITL 117-118, 79-84.

Mason, B. & Krashen, S. (1997b). Extensive reading in English as a foreign language.

System, 25 (1), 91-102.

Mori, S. (1999). The role of motivation in the amount of reading. Temple University Japan Working Papers in Applied Linguistics, 14, 51-68.

Mori, S. (2001). The effects of proficiency and group membership on motivation to learn and read in English. The Proceedings of the Third Temple University Japan Applied Linguistics Colloquium, 55-66.

Mori, S. (2002). Redefining motivation to read in a foreign language. Reading in a Foreign Language, 14 (2), 1-16 [online journal].

Mori, S. (2004). Significant motivational predictors of the amount of reading by EFL learners in Japan. RELC Journal, 35 (1), 63-81.

207

Nation, P. & Ming-tzu, K. (1999). Graded readers and vocabulary. Reading in a Foreign Language, 12 (2), 355-380.

Ono, L., Day, R., & Harsch, K. (In press). Tips for reading extensively. Forum Magazine.

Renandya, W. & Jacobs, G. (2002). Extensive reading: Why aren’t we all doing it? In J. Richards & W. Renandya (Eds.), Methodology in Language Teaching: An anthology of current practice (pp. 295-302). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sheu, S. (2003) Extensive reading with EFL learners at beginning level. TESL Reporter, 36 (2), 8-26.

Takase, A. (2002). What motivates Japanese students to read English books? The Proceedings of the Third Temple University Japan Applied Linguistics Colloquium, 67-77.

Ushioda, E. (2001). Language learning at university: Exploring the role of motivational thinking. In Z. Dorynei, & R. Schmidt, (Eds.), Technical Report #23:

Motivation and second language acquisition (pp. 93-125). Honolulu, Hawaii:University of Hawaii.

Walker, C. (1997). A self-access extensive reading project using graded readers.

Reading in a Foreign Language, 11 (1), 121-149.

Wigfield, A. & Guthrie, J.T. (1997). Relations of children’s motivations for reading to the amount and breadth of their reading. Journal of Education Psychology, 89, 420- 432.

Yashima, T. (2002). Willingness to communicate in a second language: The Japanese EFL context. The Modern Language Journal, 86, i, 54-66.

Yashima, T. (2004). The influence of attitudes and affect on willingness to communicate and second language communication. Language Learning, 54 (1), 119- 152.

Yamashita, J. (2004). Reading attitudes in L1 and L2, and their influence on L2 extensive reading. Reading in a Foreign Language, 16 (1), 1-19.

208

209

210

211

概 要

多読とリーディングへの動機づけ

マシュー・アップル

2004年春学期始め、日本の大学生85人を対象に、日本語と英語両方におけ るリーディングと学習に対する態度と動機づけに関する予備調査を行った。

最初のアンケート調査の結果は、道具的志向、第1言語でリーディングにつ いての態度、第2言語と文化に対する関心、そして言語学習に対する考え方 の4つの要因に分類された。1学期間に渡る多読(ER)プログラム終了後、

ERが学生の動機づけに影響を与えたかどうかを判断するため、同一アンケ ート調査を行った。その結果によると、ER実施前と後では、アンケートの 項目における実質的な差異は見られなかった。ここでは、本研究を土台に、

より規模の大きい研究のための示唆及び今後の方向付けを論ずる。

212