Abstract

Thepurposeofthisstudy wasto explorehow thetwo seminalfactorsofcross-cultural dichotomy and thediversity in ethicseducationalstructuresaffecttheethicalbeliefsof undergraduatestudentswho intend to becomeaccounting professionalsin Japan and Australia.Priorto thiscurrentresearch,no study in accounting education literaturehas compared theethicalbeliefsbetween Japaneseundergraduateaccounting studentsand their Australian counterparts.Previousliteraturehasrevealed thattheculturaldimension of individualism/collectivism (IDV)influencesone’sethicalperception and with appropriate ethicscourseintervention an improvementin one’sethicalbeliefsand judgmentwill occur.Howeversuch studieshaveignored theimpactofethicscourseexposurein relation to otherculturaldimensionssuch ascross-culturaldichotomy and differentethics educationalstructures.Thesampleforthepresentstudy wascollected viaaquestionnaire- based survey conducted in July 2008 attwo Australian and threeJapaneseuniversities. Thissurvey achieved an effectiveresponserateof122 and 230 respectively.The UnivariateAnalysisofVariance(ANOVA)techniquewasapplied to examinepossible associationsbetween integrated ethicscoursesand students’ethicsbelief.Regardlessof culture,theresultsindicated thatstudentswho had integrated ethicscourseexposure tended to havebetterethicalbeliefsthan thosewho did notand Japanesestudentstended to encompassgroup-oriented ethicalbeliefsand theseareareflection oftheircollectivism trait.

Effectivestrategiesforsuccessfulglobalharmonization ofaccounting ethicseducation arealso discussed in thepaper.

Keywords: individualism,collectivism,culturaldichotomy,globalharmonization,IES

The Ef f e c t s of Et hi c s Cour s e Expos ur e : A Compa r a t i v e St udy Be t we e n

J a pa n a nd Aus t r a l i a

Sa t os hi Suga ha r a

(Received on August21,2009)

I nt r oduc t i on

Basic consensus has been reached by the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) on the difficulty in harmonizing one’s values or fundamentalprinciplesacrosssomenations,becausethesevaluesand principles arenormally reflected by culturaltraits.Thefactorsthatindividualsconsiderat thedifferentstagesofthedecision making processand theirrelativepowerof influencemay also vary acrossculture(Thorneand Saunders,2002).Therefore, to requireallglobalparticipantsto comply with uniform ethicalbehavior remainsvery difficult.Nevertheless,theInternationalEducation Standards prescribesaminimum setofrequirementsforprofessionalaccountantsin order to equip them with universally accepted professionalvalues,ethicsand attitudes (IFAC,IES 4,2003).Itiswidely accepted thatsomeprofessionalbehavior allowed in theeastern cultureisfrowned upon in western countriesand vice versa.Previousliteratureprovideexamplesofthisuniqueproposition,where accountantsin collectivisticenvironmentsaremorelikely to subordinate individualvaluesforthosethatbenefittheirorganization,whileaccountants from individualisticsocietiesaremorelikely to adhereto personalprinciples even iftheresultsaredetrimentalto theorganization (Smith and Hume,2005;

Waldmann,2000).Accordingly,theglobalethicseducation standardssuch as IES 4 need to play an importantroleforaccounting professionalcandidatesin orderto fillthegap caused by indigenousculturaltraitsand equip these candidateswith appropriateethicalvaluesand standards.

In responseto thisglobalharmonization in accounting ethicseducation setup by IFAC,comesthecontroversialissuethateducationalstructureswithin the accounting profession variesbetween nations.In Japan,forinstance,the accreditation schemethatisadopted frequently by othernationsisnotapplied during thedevelopmentphaseofthecurriculum.Asaresult,neitherin the

accounting tertiary curricularnorin theCPA exam schemeareCPA candidates required to includeany ethicsstudiesin theircourses.From atechnical perspective,Urasaki(2006)examined thenumberofstand-alonecoursesof accounting and business ethics at the undergraduate level. The result demonstrated thatonly 18 ofthe77 universitiessampled (23.3%)provided stand-aloneethicscourses,even though approximately 80% ofsuccessful Certified PublicAccountants(CPA)examineeshad justcompleted their undergraduatedegree(79.4% in 2007).Thestudy also found thatthemajority of Japaneseundergraduatecoursesin tertiary businessdegreesrelied on ethics intervention being incorporated voluntarily within otherbusinesssubjectsby accounting educators.Thus,thestrength ofethicseducation atthepre- qualification stageofaccounting education appearsquitelow.Thishasresulted from theIESs,allowing globalmemberscertain flexibility when incorporating ethicseducation into theirpre-and post-qualification programs(IAESB,2007). TheIFAC (orIAESB)doeshoweverarticulatethattheIESsmay becomplied with by using avariety ofdifferentmethods.Consequently,in Japan for instance,theJapaneseInstituteofCertified PublicAccountants(JICPA)makeit compulsory forallmembersto completesomeform ofannualprofessional ethicstraining undertheContinuing ProfessionalEducation (CPE)scheme during thepost-qualification phase.

Howeveritisnotclearwhetherthepresentethicseducationalstructuresare effectivein affirming theuniversalqualitiesso eagerly soughtby theIESs.As discussed above,theaccounting ethicseducationalstructurein Japan islikely to remain quiteuniquein comparison with structuresfrom western countries.Prior research hasignored theeffectofethicseducation among CPA careerdestined Japanesestudentscompared to similarstudentsfrom western countries.A major issueremainson whetherboth theseculturalgroupingsperceivean ethicalissue similarly ordifferently?Ifthey aredifferent,then how effectivedoesethics

education work forthem to improvetheirbeliefs?Putanotherway doesethics education only work foroneculturalgroup attheexpenseoftheothergroup or doesitin factwork simultaneously forboth groups?Thisstudy aimsto investigateand solvetheseresearch questions.

To exploretheeffectofethicseducation on Japanesestudents,thisstudy used Australian undergraduatestudentsasthewestern counterpartin orderto investigatethedegreeto which students’culturaldichotomy underpinsthe effectivenessoftheirethicscourseexposure.Thischoiceseemsquitefeasibleas theeducationalstructureand delivery methodsfortheaccounting profession in Australiaaresomewhatdifferentfrom thosein Japan and so an effective comparison isviableforourresearch purpose.In Australia,theconceptsof business and accounting ethics are basically introduced during their undergraduatestudiesasrequired by theprofessionalaccounting bodies’ accreditation process(O’Leary and Radich,2001).To becomeamemberof accounting professionalbodiesand work asaChartered Accountant,Graduates enrolling into theChartered AccountantsProgram arerequired to hold a recognised Australian degreeoran overseasqualification ofastandard approved by theInstitute,and havecompleted studies.With regard to thisethics education,theaccreditation guidelineexpectshighereducation providersin Australiato referto ethicaldecision-making models,principlesand values acrossthecurriculum ofaccredited programsand,wherepossible,encourage debateon ethicalissuesbased on practicalcases(ICAA and CPA Australia, 2009,p.18).Sincetheprofessionalbodiesin Australiasuch asCPA Australia, theCIAA and theNationalInstituteofAccountants(NIA)areallmember bodiesoftheIFAC,they havean obligation to comply with thisIES.

Given abovebackground,theaim ofthisstudy isto explorehow theseminal factorsofcross-culturaldichotomy and thediversity ofeducationaldelivery affectto theethicalbeliefsofundergraduatestudentswho pursuitto becomethe

accounting professionalsin Japan and Australia.Thisstudy also investigatesthe differencesin theeffectsofethicslearning exposureamong two studentsgroups from both countries.

Thepaperproceedsasfollows.Thenextsection comprisestheliterature review culminating in thedevelopmentofthehypotheses.Thefollowing section describestheresearch method and thestatisticaltechniquesused in theanalyses. Thesubsequentsectionspresentstheresultsand interpretation with the concluding remarksincorporating potentiallimitationsofthestudy.

Li t e r at ur e r e vi e w and hypot he s e s de ve l opme nt

1)Theimpacton one’sethicsabilitiesfrom culturaldichotomy

Earlierstudiesin theliteraturehaveexplored theculturalimpacton one’s ethicsability by using Rest’sDefining IssuesTest(DIT).TheseDIT studies havechosen two nationswhereculturaltraitsrepresentdichotomy to investigate possibleassociationsbetween one’sethicalreasoning ability and nationality difference.Forexample,thedifferencesin ethicalreasoning ability were addressed with thesampleofauditorsfrom US and Hong Kong (HK)by Tsui (1996),and thosefrom Australiaand Chinaby Tsuiand Windsor(2001).Both studiesconcluded thatprofessionalauditorsfrom western countries(US and Australia)tended to havehigherethicalreasoning ability than theirnon-western counterparts(HK and China).

Along similarlines,otherresearch hasexamined theculturalimpactson variousprofessionaljudgments.Cohen etal.(1995)forinstanceexplored the differencesin theethicaldecision-making among auditorsfrom thethreenations ofLatin America,Japan and theUnited Stateswho wereemployed in one multinationalaccounting firm.In thestudy,subjectswereasked to providetheir ethicaljudgmentson auditspecificvignettes,which contained culturaldilemmas thatmightbeconsidered questionableaccording to Hofstede’s(1980;1983;

2001)fiveculturaldimensions.Theresultdemonstrated significantdifferences in ethicaljudgmentsorintentionseven though allsubjectswerefrom thesame firm,and subjectto thefirm’sown ethicscode.Forexample,itwasfound that theJapanesegroup wassignificantly morelikely than theUS and Latin American groupsto statethatthey would understateactualhoursworked in orderto keep within thebudget.Thisresultwasinterpreted to reflectthenotion oftaking careofthein-group,which representsthecollectivism trait.

Similarly,Patel(2003)empirically examined theculturaldifferencesin the professionaljudgmenton whistle-blowing among Australian,Indian and Chinese-Malaysian accountants.Considering theculturaldichotomy existing between Australia(western)and Indian/Malaysian (asian),theresultsindicated thattheAustralian group wasmorelikely to and moreaccepting ofengaging in whistle-blowing than theIndian and Malaysian groups.Cherry etal.(2003)also compared Taiwanese and US marketing practitioners to investigate the differencein theirperceptionstowardsseveralethicaldilemmas.With these dichotomousclustersclassified in termsofHofstede’sdimensions,theresult revealed thatTaiwaneserespondentsexhibited lowerperceptionsofan ethical issueaddressed on bribery than theirUS counterparts.Although thesestudies successfully found statisticaldifferencesin ethicalabilities,they simply utilized nationality as a proxy for culture and failed to identify which cultural dimensionsaffected theactualethicalperceptionsorbehaviour.

In contrast,amorerecentstudy by Smith and Hume(2005)specifically addressed thetwo culturaldimensionsofindividualism/collectivism and power distanceto investigatetheinfluencethatthesetwo dimensionshaveon one’s ethicalbeliefs.Thesubjectsofthisstudy wereprofessionalaccountantswho wereemployed in theUS,HK,New Zealand,Netherlands,Mexico and Venezuela.Using survey instrumentsfrom priorstudies,thisstudy attempted to exploreethicsbeliefsexisting in across-culturalaccounting work-environment.

Theresultssupported theproposition ofindividualism/collectivism where accountantsin individualisticsocietiesaremorelikely to adhereto personal principles even if the results are detrimental to the organization, while accountantsin collectivisticsocietiesaremorelikely to subordinateindividual valuesforthosethatbenefittheirorganization.Similarresultswereshown by Teoh etal.(1999)whereIndonesian studentspossessing collectivetraitstended to perceiveagreateramountofgain ifthisgain impacted moreon theirgroup compared to Australian studentswho basically havean individualisttrait.

Although thiscurrentliteraturereview revealsthatmany priorstudies attempted to comparethedifferencesin ethicsperceptionsand beliefsacross countries,mostofthem simply used nationality asaproxy forcultureand failed to considerthespecificdimension ofculturaldichotomy in theiranalyses. Among them,only thestudy by Smith and Hume(2005)statistically addressed two particularfactorsofHofstede’sfiveculturaldimensionsand found that individual’s ethical behaviours are significantly subjected to the Individualism/Collectivism (IDV)dimension.According to Hofstede(2001),the IDV dimension isreferred to astherelationship between theindividualand the collectivity notion thatprevailswithin agiven society.When dealing with a collectivisticculture,socialmemberswould beexpected to putthebestinterests ofthegroup ororganization beforethoseoftheindividual.When dealing with ethicalissuesthathavean effecton theorganization,asawhole,itisexpected thatindividualsfrom collectivisticcultureswillsubordinatethebestinterestof theindividualforthegreatergood oftheorganization (Cohen etal.,1993). Therefore,when deciding whatisbestfortheorganization,pressureisputon individualsto chooseunethicalbehaviour,with such actionsoften deemed acceptablein collectivistcultures.

In thisstudy,theimpactofIDV dimension willbeinvestigated with two dichotomousdatapopulations:onefrom thecollectivism Japan and theother

from individualism Australia.Australiaisbased on Anglo-Saxon heritagewhile Japan islocated in thatpartofAsiawhereConfucianism widely prevailsand affectsits’peoplesbehaviourand values.Hofstede(1980;1983;2001)also found thatJapan and Australiaareculturally dichotomousin termsoftheIDV dimension.Theindex scoresfortheIDV illustrated by Hofstede(1980;1983;

2001)were46 forJapan and 90 forAustralia.Accordingly thefirsthypothesis, developed in nullform,investigatesthedichotomoustraitoftheJapaneseand Australian samplegroupsin termsofethicalbelief.

H1:Students’ethicalbeliefsthatreflecttheirindividualism/collectivism dimension in addressing ethicalissuehaveno significantassociation with theirnationalitydifference.

2)Theimpacton ethicalbeliefsfrom thediversityin ethicseducational structureacrossculture.

Therehasbeen generalconsensusin themajority ofpreviousethicsliterature thatethicscourseexposurehassignificantinfluenceon developing individual ethicaljudgments(e.g.Earley and Kelly,2004;Massey 2002;Thorne,2001) and ethicalperceptions(e.g.O’Leary,2008;Bodkin and Stevenson,2006). Among such literature,somestudieshavediscovered theinfluencethatcultural dichotomy ofwestern and eastern environmentshaveon ethicseducation.For example, Cohen et al. (1992) contended that the collectivist conceptual framework producesdifferentviewsfrom thoseofindividualism especially in termsofnepotism,employerloyalty and giftgiving.Itwasconcluded thatsuch culturalcontradictionsmightlimittheeffectivenessofapplying theinternational codeofethicsto certain nations.Thispriorstudy anecdotally highlighted the theoreticalprescription ofculturalimpacton theeffectofethicseducation.More recently,Lopezetal.(2005)attempted to exploreempirically thenotion that

ethicseducation isdriven by ethnicity in determining one’sethicalperceptions. Lopezetal.(2005)examined theeducationaleffectofintegrating ethicscourses into amulticulturalbusinesscoursein aUS university.Theirfindingsreported a significantand positiveimpactrelating to thetwo perceptionsoffraud and coercivenessfortheAmerican group,whilethethreeperceptionsoffraud, influencedealing and coercivenesswereperceived by aHispanicgroup.The study produced evidenceon thepositiveeffectthatethicslearning experiences hason students’cognitivebehaviourwith such relationship varying according to one’sethnicity.

In addition to theimpactthatculturaltraitshaveon one’sethicaljudgments, anotherresearch linehasemphasized thefactthatone’sethicalperceptionsand behaviourarehighly influenced by thediversity in structuresthathavebeen found to existin ethicseducation among variousnations(e.g.Rest,1994;

Okleshen and Hoyt,1996).Thisimpacthoweverisoften uncleardueto the difficulty in distinguishing theeffectofethicslearning from intrinsiccultural dichotomy and externalinfrastructuralschemefactors.Regarding thisconcern, Okleshen and Hoyt(1996)successfully distinguished theeffectofthelatter externalinfrastructurefactor.Thestudy examined whetherbusinessethics coursesorspecifictraining enhancesone’sethicalperceptionsusing two nationality groups.They found thatboth New Zealand and US studentswere commonly moreawareofethicalissuesafterthey had been exposed to an actual learning experiencein ethics.Specifically,theresultfound thatUS students tended to bemoretolerantin fouroutofthefiveethicaldomainsthan theirNZ counterpartswhen both studentgroupsdid nothavespecificcourseexperience. Theauthorimplied thatsuch lowerawarenessby NZ studentscompared to their US counterpartswaspartly becausetheintegration ofethicsinto business curriculum can bemoreadvanced in theUS.Such research findingsindicate thatthevariousstructuresexisting in ethicseducation may havedifferent

impactson thelevelofstudents’ethicalperception.

To provideabetterunderstanding thiscurrentstudy also attemptsto identify moreclearly theimpactthatthediversity ofethicseducationalstructureshason students’ ethics beliefs across two dichotomous groups. As previously mentioned,accounting ethicseducation in Australiaisbasically incorporated into arangeofsubjectsacrossthecurriculum with such approachesrequiring accreditation by governmentagencies(IACC and CPA Australia,2009).In Japan however,tertiary schoolsarefreeofgovernmentaccreditation and so,at thediscretion oftheinstructor,arevery flexiblein thedelivery ofethics education,ranging from incorporating itinto any section ofthecurriculum to ignoring italtogether.Nevertheless,such alack ofcourseexposureon ethicsfor professionalcandidatesin Japan can besupported to somedegreeby training coursesatthepost-qualification stageprovided by theJICPA (FSA,2002). Regardlessofnationality differences,ifstudents’leaning exposuresin ethics doescorrelatesignificantly with theirethicalbeliefs,then theresultofthis investigation willenableusto ensuretheeffectivenessofethicsteaching in both countries.On theotherhand,ifstudents’learning exposureto ethicscorrelates with one’sethicalbeliefbased on nationality then theresultswillimply thatthe nationality differencein teaching delivery causessuch agap in ethics.To addressthisquestion,thesecond research hypothesiswasdeveloped in null form asfollows.

H2: Students’ ethical beliefs that reflect the individualism/collectivism dimension in addressing ethicalissueshasno significantassociation with thediversityofethicscoursedeliverywhich arereflected bythenations’ educationalstructures.

Re s e ar c h me t hod

QuestionnaireDevelopment

To investigatethehypotheses,thepresentstudy developed aquestionnairein orderto collectresearch data.Thequestionnairecomprisestwo sections.The firstsection containsthreework-environmentstatementsthatwereevaluated by thestudentrespondentswho participated in thissurvey.Thestatements (assessing questionableethicalbeliefsand behaviors)allow therespondentsto reflecton theirown individualculturalbeliefswhen addressing ethicalissues. Thesesurvey itemswereadapted from surveysused in severalpriorstudiesthat werereferred to in Smith and Hume(2005).TheoriginalEnglish version was used forthesurvey administered in Australia.In Japan,theoriginalitemswere translated into Japanese.To confirm thereliability ofthetranslation,theback- translation techniquewaspiloted with somecolleagueswho werenative Australian and Japanese.A five-pointLikertscalewasused to measuretheir responses,which wereanchored 1 forstrongly agreeand 5 forstrongly disagree.

In thesecond section ofthequestionnaire,subjectswereasked background information including age,gender,nationality atbirth,learning experienceand itsduration ifoverseas,academicyearand job experience.Additionally,this section carefully soughtrespondents’courseexposuresin termsofwhetherthey currently haveorpreviously havehad integrated courseexposureduring their

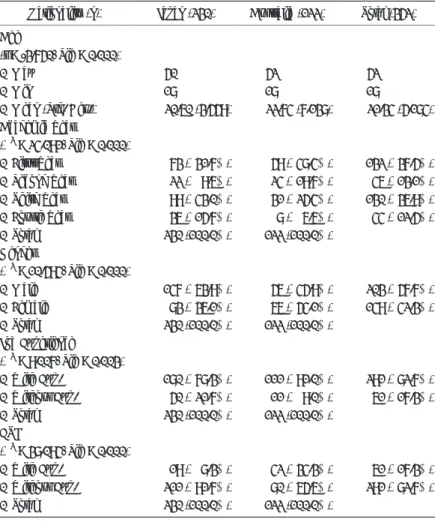

Figure1 :EthicalSurvey Items

Itisacceptableto compromisemy own principlesto conform to yourorganization’s expectations.

1

An employeeshould overlook otheremployees’questionableactionsifitisin the bestinterestofthecompany.

2

Sometimes,itisacceptableforan employeeto lieto acustomer/clientto protectthe interestofthecompany.

3

undergraduateyears.Although theseminalissueofethicsinstruction involves theargumenton whetherethicsshould betaughtasastand-aloneunit(e.g.

Hanson,1987;Loeb,1998)orintegrated into othercourses(e.g.Bodkin and Stevenson,2007;Swanson,2005;Thomas,2004),thepresentstudy addressed students’learning exposurefrom an integrated courseperspective.Thiswas simply forcomparativereasonsasin Australiaethicsbeing integrated into accounting unitscomplieswith theaccreditation process(ICAA and CPA Australia,2009)whilein Japan themajority ofundergraduatetertiary business degreesrely on ethicseducation being incorporated into businesscourses voluntarily by theinstructor(Urasaki,2006).

SampleCollection

The data for the present research was collected via a questionnaire administered to undergraduatestudentstaking coursesrelating to accounting in both Japan and Australia.In thisresearch,studentswho wereeitherborn in Japan orin Australiawereselected asthesamplein orderto clearly addressthe culturaldimension ofIndividualism/Collectivism.Internationalstudentswere eliminated from thesamplein both countries.To achievethis,thequestionnaire wasinitially distributed to allstudentswho attended electivecoursesin accounting regardlessoftheirdemographicbackground.From thissetof respondents,asub-setofstudentswho wereborn in eitherJapan orAustralia and had nothad any overseaslearning experienceswereidentified and used.

Thedatacollection wasanonymouswith respondentsnotrequired to record theirnamesorID on thesurvey instrument.

Questionnairesweredistributed to 263 studentsacrossthreeuniversitiesin Japan and 225 studentsattwo universitiesin Australiain themonthsofJuly and October2008 respectively.From theresponses,somewerediscarded dueto the unsuitability ofthenationality atbirth,learning experiencesoverseasand

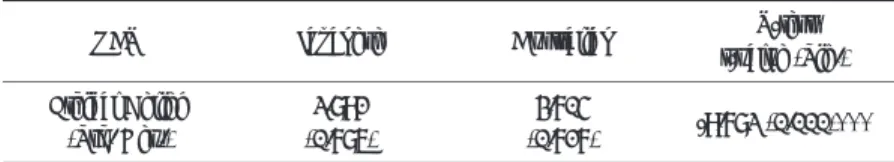

questionnaireincompletion.Accordingly,thenumberofeffectiveresponseswas 230 forJapanesestudentsand 122 forAustralian studentsgiving an effective rateof87.5% and 54.2%,respectively.Thelowerrateofeffectiveresponsefor theAustralian samplewasdueto theirlargerproportion ofinternationalstudents. Table1 providesthedescriptiveinformation forthesamples.To examine comparability between theJapaneseand Australian studentgroups,thisstudy

Table1:DescriptiveInformation oftheSample

Total(352) Australia(122)

Japan (230) Nationality (n)

Age

(t= -3.750,Sig = 0.000)

52 52

50 Max

18 18

18 Min

21.34 (5.184) 22.74 (7.138)

20.60 (3.559) Mean (Std.Dev.)

AcademicYear

(c2= 24.091,Sig = 0.000)

132 ( 37.5%) 59 ( 48.4%)

73 ( 31.7%) FirstYear

46 ( 13.1%) 24 ( 19.7%)

22 ( 9.6%) Second Year

130 ( 36.9%) 31 ( 25.4%)

99 ( 43.0%) Third Year

44 ( 12.5%) 8 ( 6.6%)

36 ( 15.7%) Fourth Year

122 (100.0%) 230 (100.0%)

Total Gender

(c2= 10.594,Sig = 0.000)

203 ( 57.7%) 56 ( 45.9%)

147 ( 63.9%) Male

149 ( 42.3%) 66 ( 54.1%)

83 ( 36.1%) Female

122 (100.0%) 230 (100.0%)

Total Job Experience

(c2= 9.007,Sig = 0.003)

291 ( 82.7%) 111 ( 91.0%)

180 ( 78.3%) With Exp.

61 ( 17.3%) 11 ( 9.0%)

50 ( 21.7%) WithoutExp.

122 (100.0%) 230 (100.0%)

Total ETH

(c2= 38.094,Sig = 0.000)

61 ( 17.3%) 42 ( 34.3%)

19 ( 8.3%) With Exp.

291 ( 82.7%) 80 ( 65.6%)

211 ( 91.7%) WithoutExp.

122 (100.0%) 230 (100.0%)

Total

applied apreliminary t-testto investigatedifferencesin age.Chi-squaretests werealso used atthisinitialstageto examinedifferencesin academicyear, gender,job experienceand integrated courseexposurein ethics(ETH).The resultsofthesepreliminary analysesdemonstrated significantdifferencesin age through thet-testatthe0.01 level.TheChi-squaretestsalso found that academicyear,gender,job experienceand theETH werenotequally distributed with significantevidenceatthe0.01 level.Sincetheseattributesleftopen the question ofhomogeny among thetwo nationality groups,theinfluencethese preliminary results may have must be considered when drawing final conclusions.

In termsofthequality in highereducation,both countriesarecommonly regarded asbeing welladvanced.Thelatest2009 university ranking,released by TimesHigherEducation (http://qqq.timeshighereducation.co.uk),shows severaluniversitiesfrom both Japan and Australiaasbeing ranked among the top 200 institutionsin theworld.From an accounting education perspective,the accounting professionalbodiesin both countriesaremembersoftheIFAC,and so areexpected to incorporatetheIES’sinto theirown education system.

AnalysisTechniques (1)T-testanalysis

A t-testanalysiswasperformed to addresshypothesisH1.Thistechniquewas used to investigateand comparepossibledifferencesin ethicalbeliefsbetween Japaneseand Australian students.Theirethicalbeliefswererepresented by the mean scoresofstudents’responsesto threesurvey items.Forthist-test,the ethicalbelief(EB)aggregated from students’responsesto thesethreeitemswas used asthedependentvariableand thenationality difference(oneforJapanese; two forAustralian)wasused astheindependentvariable.

(2)UnivariateAnalysisofVariance

A univariateanalysisofvariancetechnique(ANOVA)wasapplied to address hypothesisH2,whererespondents’ethicalbeliefsthatmaybeaffected by the interaction between theirnationality and ethicslearning exposureswere examined.When applying thisstatisticaltechnique,an aggregated mean score from student’sethicalbeliefs(EB)wasconsidered asthedependentvariable with nationality (NAT)and students’responseon whetherornotthey havehad an ethicslearning experience(ETH)astheindependentvariables.

Re s ul t s

T-testResult

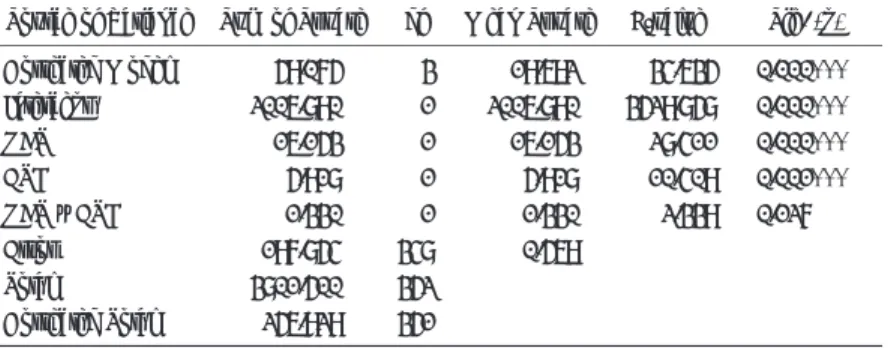

A t-testanalysiswasconducted to addresshypothesisH1.Theaveragescores forethicalbeliefs(EB)werecompared between studentsfrom Japan and Australia.Table2 showstheresultsofthist-test,which found differencesin students’EB scoresbetween thetwo nationality groupsatthe0.01 level(t- value= -9.782,p = 0.000).Thecomparison ofaverageEB scoresdemonstrated thatAustralian studentshad asignificantly higherEB score(3.704)than their Japanesecounterparts(2.891).Thisresultconfirmed thathypothesisH1 mustbe rejected on astatisticalbasis.

UnivariateANOVA Result

A univariateANOVA wasperformed forH2 to analysetheimpactof interaction between students’nationality (NAT)and ethicscourseexposure

Table2:T-testResultofIDV/COL ethicalsensitivity forNationality Difference T-test t-value(Sig.) Australian

Japanese NAT

-9.782 (0.000)***

3.704 (0.717) 2.891

(0.786) EthicalBelief

(Std.Dev.)

*** significantatthe0.01 level

(ETH)toward theirethicalbeliefsassociated with theindividualism/collectivism (IDV)dichotomy.Table3 showstheresultforthistesting.Firstly,theresult exhibitsthattherelevanceoftheoverallmodelwassignificant(F-value= 34.635,p = 0.000)with an R2 of0.230 (0.223).Levene’stestofequality of errorvarianceswascalculated with an F-valueof1.083 (p = 0.356),which resultsin afailureto rejectthenullhypothesisthattheerrorvarianceofthe dependentvariableisequalacrossgroups.Thisresult,using Levene’stest, confirmsthevalidity oftheunivariateANOVA being used in thisanalysis.

Secondly,theunivariateANOVA also demonstrated thatthemain effectof nationality (NAT)and ethicslearning exposure(ETH)significantly affects students’ethicalbeliefs.Thedetailsoftheseresultswereexhibited astheresult ofunivariatetestin Table4 and Table5 forthenationality (NAT)and ethics learning exposure (ETH) respectively. Table 4 displays the significant

Table3:TheResultsofUnivariateANOVA

Sig.(p) F-value

Mean Square df

Sum ofSquare SourceofVariance

0.000***

34.635 19.692

3 59.075 Corrected Model

0.000***

3529.858 2006.890

1 2006.890 Intercept

0.000***

28.411 16.153

1 16.153 NAT

0.001***

10.409 5.918

1 5.918 ETH

0.127 2.339 1.330

1 1.330 NAT x ETH

0.569 348

197.854 Error

352 3801.500 Total

351 256.929 Corrected Total

*** significantatthe0.01 level

ThedependentvariableisEthicalBelief(EB)from respondents.

R2 =0.230 (Adjusted R2 =0.223),Levene’sTestofEquality (F=1.083,Sig.=0.356) Note:theabbreviationsused in thisTablestand forfollowing variables.

EB = Five-pointLikertscale,whereoneforstrongly agree;fiveforstrongly disagree NAT = OneforJapanesestudents;two forAustralian students

ETH = Oneforlearning experienceforintegrated ethicscoursematerialsatthetertiary school;zero forno learning experienceforintegrated ethicscoursematerialsat thetertiary school

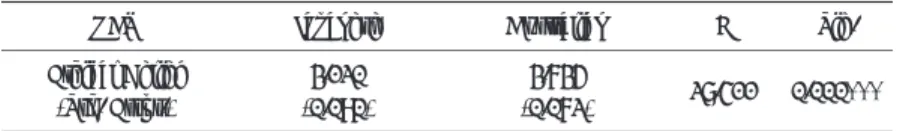

differencesin averageethicalbelief(EB)between studentsfrom Japan and Australiaatthe0.01 level(F-value= 28.411,p = 0.000).According to this result,theAustralian studentgroup had significantly higheraverageEB score (3.735)compared to theirJapanesecounterparts(3.120).Table5,also shows significantdifferencesin theaverageEB scorebetween studentswho had ethics learning exposureand thosewho did notatthe0.01 level(F-value= 10.409, p = 0.001).Theresultsindicatethatstudentswho had ethicslearning exposure had significantly higheraverageEB scorethan thosewho did nothavesuch exposure.

Finally,theunivariateANOVA in Table3 also displaysthattheinteraction effectofnationality (NAT)and ethicslearning exposure(ETH)did not significantly affectrespondents’ethicalbeliefs(F-value= 2.339,p = 0.127), whiletheeffectofNAT (F-value= 28.411,p = 0.000)and ETH (F-value= 10.409, p = 0.001) did show significant associations with students’ EB.

Consequently,theunivariateANOVA ofthisstudy failed to rejecthypothesisH2.

I nt e r pr e t at i on

Firstly,theresultfrom thet-testanalysisrevealed thattheAustralian student Table4:UnivariateTestfortheEffectofNationality difference

Sig.

F Australian

Japanese NAT

0.000***

28.411 3.735

(0.072) 3.120

(0.090) EthicalBelief

(Std.Error.)

*** significantatthe0.01 level

Table5:UnivariateTestfortheEffectofEthicsLearning Experience Sig.

F WithoutExperience With Experience

ETH

0.001***

10.409 3.242

(0.050) 3.614

(0.104) EthicalBelief

(Std.Error.)

*** significantatthe0.01 level

group had significantly higher average ethical beliefs that reflect the individualism/collectivism dimension compared to theirJapanesecounterpart. Thisfinding indicatesthatJapanesestudentstend to putpressureon one’s choiceand preferwhatisthebestforthegroup dueto theirculturaltraitof lowerindividualism (highercollectivism)than Australian students.This interpretation isconsistentwith thefinding by Smith and Hume(2005).While thesamplesofthispriorstudy wereprofessionalaccountantsand did not contain JapaneseorAustralians,thepresentstudy affirmed similarevidence using undergraduatestudentsthatone’sethicalbeliefsaresignificantly influenced by theirindividualism/collectivism dimension.Moreoverthefinding ofthispriorstudy wasalso supported by Teoh etal.(1999),which found similarassociationsbetween individualism and theirethicalperceptionsusing studentsfrom Indonesiaand Australia.Similarly,theindividualism/collectivism contradiction on ethicalbeliefswasconfirmed by thepresentstudy using the differentwestern/eastern samplesofAustralian and Japanesestudents.

Secondly, the results of the univariate ANOVA reported significant correlationswith both students’nationality and ethicscourseexposureson their ethicalbeliefsthatreflectan individualism/collectivism dimension.Among these two main effects,theresultfortheeffectofnationality showed themost significantrelationship with students’ethicalbeliefs.Thisresultensuresthe statisticalevidenceofthet-testmentioned abovewhereJapanesestudentstend to putmorepressureon one’sethicalchoicesand givepreferenceto group benefitsdueto theirculturaltraitoflowerindividualism than do theAustralian students.

Students’ethicscourseexposurealso produced asignificantrelationship with ethicalbeliefs.Thisfinding isinterpreted asbeing forthosestudentswho do not haveethicslearning exposuretend to subordinateindividualbeliefsin orderto choosewhatisthebestfortheirgroup,whilethosewho havelearning exposure

in ethicstend to respecttheirown beliefand avoid whatisthebestinterestsfor theirparticulargroup.Thisfinding indicatesthatstudentsfrom thesampleof undergraduatestudentswho takeethicscoursesareinclined to assessethical issuesmoreindependently from theirindigenousculturaltrait.Previousstudies also supportthepresentfinding thatethicscoursesaresignificantly effectivein improving one’sethicsperceptions(e.g.O’Leary,2008;Bodkin and Stevenson, 2006)particularly in integrated ethicscoursesprovided atthetertiary level. Despitethecontroversy on how ethicsissuesshould bebestprovided in the accounting curriculum (Bodkin and Stevenson,2006;Swanson,2005;Thomas, 2004),evidencefound in thepresentresearch contributesto theliteratureby supporting thestrength ofintegrated courses.

Theaboveoutcomeshoweverdo notdraw theappropriateresponseforthe research goalofthepresentstudy,which aimed to investigatetheimpactof cross-culturaldiversity in ethicscoursestructuresbetween Japan and Australia. Ultimately,higheraveragescoresin ethicsbeliefforstudentswith course exposuremay simply betheresultofthelargecontainmentofAustralian studentsin thegroup who had courseexposures.SinceAustralian studentsare basically expected to takeintegrated ethicscoursesovertheduration oftheir degreedueto theprofessionalaccreditation scheme,thehigherproportion of Australianswho originally havehigherscoreofethicalbeliefscould be estimated in thegroupswith ethicscourseexposure.In responseto this question,theinteractiveeffectofnationality and ethicslearning exposure towardsethicsbeliefswasexamined by theunivariateANOVA.According to theresult,thisinteraction effectfailed to find any significantimpacton ethical beliefamong respondents.Thisresultindicatesthatthedifferencesin theeffect ofcoursesexposurecould notbedistinguished between thetwo nationson a statisticalbase.Whileethicscoursestructuresin tertiary schoolsvary widely between Japan and Australia,thisanalysisresultindicatesthattheeffectiveness

ofethicscourseexposureshasnotbeen influenced by thecross-cultural diversity in educationalstructures.

Compared with thepresentstudy,Okleshen and Hoyt(1996)investigated ethicalawarenessamong studentsfrom theUS and New Zealand,and concluded thatthegap in theirawarenessdependson whethertheethicscurriculumsare welldeveloped ornotin theirparticularcountry.In contrastthenon-significant resultfortheinteractiveeffectbetween nationality and courseexposurein the presentstudy impliesthattheeffectivenessofethicscoursedelivery isquite high forstudentsfrom both countriesregardlessofthecross-culturaldiversity in educationalstructures.Instead,thegap in ethicsbeliefsbetween nationsis attributed to thestudents’culturaldichotomy oftheindividualism/collectivism dimension.

Conc l udi ng r e mar ks

Thepurposeofthisstudy wasto explorehow thetwo seminalfactorsof cross-culturaldichotomy and thediversity ofethicseducationalstructuresaffect theethicalbeliefsofundergraduatestudentswho intend to becomeaccounting professionalsin Japan and Australia.Priorto thiscurrentresearch,no study in accounting literaturehasexplored ethicalbeliefsamong Japaneseundergraduate accounting studentsand compared them with thedichotomousculturaltraitof theirAustralian counterparts.ThefindingsindicatethatJapanesestudentstended to encompassgroup-oriented beliefsin ethicsand thesereflecttheircollectivism trait.

Itwasalso found thatstudentswho havehad moreformalethicslearning tended to possessmoreindividual-oriented beliefsin ethicscompared to those who did nothavesuch experiencesregardlessoftheethicseducation structures existing within theirnation.ThisresultsupportstheIESs’provision ofallowing educatorsin participantnations,forexampleJapan and Australia,to adopt

flexibleapproacheswhen delivering ethicscoursesin an attemptto avoid potentialgapsin ethicseducation acrosstheglobe.ForJapanesestudents,these resultscan beinterpreted to mean thatby exposing studentsto ethicscoursesit willeffectively lessen theirgroup-oriented ethicsbelief,which isrelatively common in collectivistsocieties.In otherwords,moving towardsindividualism thepresentethicseducation facilitated by Japanesetertiary schoolsenablestheir students’ethicsbeliefsto becomemorewesternised.

Nevertheless,therestillremainsagap in ethicsbeliefsdueto theexisting cross-culturaldimension ofindividualism/collectivism between Japaneseand Australian students.A preferablemethod to harmonizethisdiscrepancy isto increasetheproportion ofcourseexposurein ethicsforJapaneseundergraduate students.Thedescriptivedatain thisstudy revealed thatJapanesestudents receivelessopportunity to learn ethicsthan Australian studentsin their respectiveaccounting programs(seeTable1).Although Japan hasnotadopted in its’accreditation system acompulsory integration ofethicsatthepre- qualification stagein accounting JICPA’svoluntary training coursesin ethicsat post-qualification do provideaminorinformalsubstitute.Even so thecurrent study successfully providesevidencethatformalethicscoursesarean effective method to improvestudents’ethicsbeliefs.Thereforeappropriatereform which reinforcestheneed formoreethicscourseexposureto Japanesestudentsisa practicalway to achieveinternationalharmonization in accounting ethics education.

Thepresentstudy doeshaveseverallimitationswhich may haveinfluenced theresultsofthisstudy.Firstly,theanalysisonly addressed theissueofethics within thecontextofwhereitwasintegrated with othercourses.Previous literatureregarding theeffectivenessofethicseducation haveargued the appropriatenessofethicsbeing taughton eitherastand-alonebasis(e.g.Hanson, 1987;Loeb,1998)orintegrated with othercourses(e.g.Bodkin and Stevenson,

2007;Swanson,2005).Stand-alonecoursesareoffered voluntarily in thetertiary institutionsofboth Japan and Australia,so afuturestudy could focuson these specificcourseswhen examining theimpactculturalfactorshavetoward the effectivenessofethicscourseamong thestudentsfrom thesetwo countries. Secondly,theculturaldimension explored within thisstudy waslimited to the individualism/collectivism dimension.Hosftede’scross-culturalstudy includes anotherfourdimensionsofpowerdistance,uncertainty avoidance,long-term orientation and masculinity/femininity (Hofstede,2001).Thus,thepresent research doesnotcomprehensively incorporateallfivedimensionswithin the modelexamined and again thislack ofcoveragecan beextended in future research.Finally,itcould beperceived thatoneofthemostprominentoutcomes emanating from thisstudy isbased on thepremisethatindividualism oriented ethicalbeliefsisregarded asbeing morepreferable.By relying on thisoutcome itcould thereforebeassumed thatonly ethicscoursesthathavebeen examined in thisstudy arelikely to beeffectivein closing potentialgapsin ethics education.However,thispremiseishighly dependenton theprincipleand value prevailed in thewestern countries.To simplify themodeltheapproach taken in thisstudy hasbeen to ignorepossibledebateon whatmay beconsidered to be thedefinition ofuniversally accepted ethics.Thisargumentshould also be considered in future research. Apart from these limitations, this study contributed to abetterunderstanding oftheeffectivenessofethicslearning exposuretowardsethicsbeliefsamong undergraduatestudentsin Japan and Australia.

Bibliography

Baetz,M.C.and D.J.Sharp (2004)Integrating EthicsContentinto theCoreBusiness Curriculum:Do Coreteaching MaterialsDo theJob?,JournalofBusinessEthics, 51(),pp.53–62.

Beekun R.I,R.Hamdy,J.W.Westerman and H.R.HassabElnaby (2007)An Exploration ofEthicalDecision-making Processesin theUnited Statesand Egypt,Journalof BusinessEthics,82(Sep)pp.587–605.

Bodkin,C.D.and T.H.Stevenson (2007)University students’perceptionsregarding ethicalmarketing practices:Affecting changethrough instructionaltechniques, JournalofBusinessEthics,72 (),pp.207–228.

Cherry J.,M.Leeand C.S.Chien (2003)A cross-culturalapplication ofatheoretical modelofbusinessethics:Bridging thegap between theory and data,Journalof BusinessEthics,44 ()pp.359–376.

Cohen,J,R.,L.W.Pantand D.J.Sharp (1995)An Exploratory Examination of InternationalDifferencesin AuditorsEthicalPerceptions,BehavioralResearch in Accounting,7,pp.37–64.

Cohen,J.R.,L.W.Pantand D.J.Sharp (1993)Culture-based EthicalConflicts Confronting MultinationalAccounting Firms,Accounting Horizons,September,pp.

1–13

Cohen,J.R.,Pant,L.and Sharp D.(1992)Culturaland socioeconomicconstraintson internationalcodeofethics,JournalofBusinessEthics,11()pp.687–700.

Earley,C.E.and P.T.Kelly (2004)A Noteon EthicsEducationalInterventionsin an UndergraduateAuditing Course:IsTherean “Enron Effect”?,Issuesin Accounting Education,19(1),pp.53–71.

Evans,F.J.and L.E.Marcal(2005)Educating forEthics:BusinessDeans’Perspectives, Businessand SocietyReview,110(3)pp.233–248.

Financial System Council (2002)A Report of Subcommittee on Certified Public AccountantsSystem:Vitalizing theCertified PublicAccountantsAuditSystem, FinancialServiceAgency,December17th.

Hanson,K.O.(1987)Whatgood areethicscourses?,AcrosstheBoard,11(7),pp.10– 11.

Hofstede,G.(2001)Culture’sConsequences-2nd ed.,California:SagePublications. Hofstede,G.(1983)NationalCulturesin FourDimensions:A Research-based Theory of

CulturalDifferencesAmong Nations,InternationalStudiesofManagementand Organization,8 (Spring/Summer),pp.46–74.

Hofstede,G.(1980)Culture’sConsequences,California:SagePublications.

InstituteofChartered Accountantsin Australia(ICAA)and CPA Australia(2009) ProfessionalAccreditation GuidelinesforHigherEducation Programs,(Sydney and Melbourne;ICAA and CPA).

InternationalAccounting Education StandardsBoard (IAESB)(2007)International

Education PracticeStatement(IEPS)1,Approachesto Developing and Maintaining ProfessionalValues,Ethics,and Attitudes,New York:IFAC.

InternationalFederation ofAccountants(IFAC)(2003)InternationalEducation Standards forProfessionalAccountants4:ProfessionalValues,Ethicsand Attitudes,New York:

IFAC.

Loeb,S.E.(1998)A separatecoursein accounting ethics:An example.Advancesin Accounting Education,1,pp.235–250.

Lopez, Y. P., P. L. Rechner and J. B. Olson-Buchanan (2005) ‘Shaping Ethical Perceptions:An EmpiricalAssessmentoftheInfluenceofBusinessEducation, Culture,and DemographicFactors’,JournalofBusinessEthics,Vol.60,No.6,pp.

341–358.

Massey,D.W.(2002)‘Theimportanceofcontextin investigating auditors’moral abilities’,Research on Accounting Ethics,Vol.8,pp.195–247.

Okleshen, M. and Richard Hoyt (1996) ‘Cross Cultural Comparison of Ethical Perspectivesand Decision ApproachesBusinessStudents:United StatesofAmerica VersusNew Zealand’,JournalofBusinessEthics,Vol.15,No.5,pp.537–549.

O’Leary,C.(2008)An empiricalanalysisofthepositiveimpactofethicsteaching on accounting students,Accounting Education:an internationaljournal,iFirstArticle, pp.1–16.

O’Leary,C.and R.Radich (2001)An AnalysisofAustralian FinalYearAccountancy Students’EthicalAttitudes,Teaching BusinessEthics,5(3)pp.235–249.

Patel,C.(2003)‘SomeCross-CulturalEvidenceon Whistle-Blowing asan Internal ControlMechanism’,JournalofInternationalAccounting Research,Vol.2,No.1, pp.69–96

Ponemon,L.A.(1993)‘Can ethicsbetaughtin accounting?’,JournalofAccounting Education,Vol.11,No.2,pp.185–209.

Rest,J.R.(1994)Background:Theory and research,in J.R.Restand D.Narvaez, Hillsdaleeds.,MoralDevelopmentin theProfessions,NJ:Erlbaum,pp.1–27.

Smith, A. & Hume, E. C. (2005) Linking Culture and Ethics: A Comparison of Accountants’EthicalBeliefSystemsin theIndividualism/Collectivism and Power DistanceContexts,JournalofBusinessEthics,62(3),pp.209–220.

Swanson,D.L.(2005)Businessethicseducation atbay:addressing acrisisoflegitimacy, Issuesin Accounting Education,20(3),pp.247–253.

Thomas,C.W.(2004)An inventory ofsupportmaterialsforteaching ethicsin thepost- Enron era,Issuesin Accounting Education19 (February),pp.27–52.

Thorne,L.and S.B.Saunders(2002)TheSocio-CulturalEmbeddednessofIndividuals’

EthicalReasoning in Organizations(Cross-culturalEthics),JournalofBusiness Ethics,35(),pp.1–14.

Thorne,A.L.(2001)Refocusing ethicseducation in accounting:An examination of accounting students’tendency to usetheircognitivemoralcapacity,Journalof Accounting Education,19(),pp.103–117.

Teoh,H.Y.,D PaulSerang and C.C.Lim (1999)Individualism-Collectivism Cultural DifferencesAffecting PerceptionsofUnethicalPractices:SomeEvidencesFrom Australian and Indonesian Accounting Students,Teaching BusinessEthics,3(2),pp.

137–153.

Tsui,J.S.L.(1996)‘Auditors’EthicalReasoning:SomeAuditConflictand Cross CulturalEvidence’,TheInternationalJournalofAccounting,Vol.31,No.1,pp.

121–133.

Tsui, J. S. L. and C. Windsor (2001) ‘Some Cross-Cultural Evidence on Ethical Reasoning’,JournalofBusinessEthics,Vol.31,No.2,pp.143–150.

Urasaki,N.(2006)‘A Survey ofAccounting EthicsEducation’,TheJournalofBusiness Administration and Marketing Strategy,KinkiUniversity;Japan,Vol.53,No.1/2,pp.

163–179.

Waldmann,E (2000)‘Teaching ethicsin accounting:adiscussion ofcross-culturalfactors with afocuson Confucian and Western philosophy’,Accounting Education:an internationaljournal,Vol.9,No.1,pp.23–35.