Trends and Forms of Timber Production Dealing

in Okukuji Area, Fukushima Prefecture, Japan

著者

SEKINE Ryohei, MIROKUJI Kouta

雑誌名

The science reports of the Tohoku University.

7th series, Geography

巻

54

号

1/2

ページ

1-23

発行年

2005

URL

http://hdl.handle.net/10097/45265

in Okukuji Area, Fukushima

Prefecture,

JapanRyohei SEKINE* and Kouta MIROKUJI**

Abstract We undertake this study to (i) investigate trends in Japanese for-estry, (ii) investigate changes in forestry policy considered in the Okukuji area and related regional action, (iii) investigate changes in the distribution of logs and timber, and (iv) document the current situation regarding log production dealers and sawing dealers. Log production dealers in the Okukuji area are divided into those with a business focus on national forests and those with a focus on private forests. Many dealers changed the forest to aim at it, and have changed their business objectives. While this has involved decreasing deal with national forests as other opportunities arose, different dealers reacted differently to new situations. When resources are rare in the Okukuji area, a dealer must be active outside the Okukuji area, but there are many dealers who market logs to the Okukuji area. Many sawing dealers source logs from the binary log market (OTDC, HSLM) in the Okukuji area, while, some dealers source logs without a clear market channel. Such dealers fulfill a customer order by direct and flexible log purchases. The themes of the Okukuji area are the monogenesis administration from the production to sales that "Valley Control System" aims at on the one hand, and the consistency with original corporate activity of dealers on the other. In addition, as the Government and the private forest owners are owners of the forest, the decline in timber serviceability in privately owned forests, in particular, creates a serious bottle-neck in the forestry sector.

Key words : forestry, Valley Control System, log production dealer, sawing dealer, Okukuji area

1. Introduction

Japanese forestry is currently in decline. The importation of

creased since 1961, and domestic forestry has declined due to a slump

timber since the second half of the 1990s. In addition, degradation of

timber has in demand forests due in-for to

* Institute of Urban Environment and Environmental Geography , Graduate School of mental Studies, Tohoku University

** Aizu Agriculture and Forestry Office, Fukushima Prefectural Government Science Reports of Tohoku University, 7th Series (Geography)

2 Ryohei SEKINE and Kouta MIROKUJI

the aging and decreasing number of foresters is of concern. Although approximately

40% of Japanese forests are plantations intended for economic use, these forests are

currently commonly neglected. The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries

of Japan (2000) identifies the following reasons for the generally poor advancement of

forestry in Japan :

1) forest owners developed an attachment to the forest.

2) forest does not require frequent work like farmland.

3) forest does not require prompt harvesting.

4) In forestry, the merits of scale are not immediately obvious.

5) The profitability of forestry has declined, and enthusiasm for forestry has

dropped.

Forestry in Japan is commonly viewed in terms of land conservation and

contribu-tion to the regional economy, however, forestry requires a long period of time from

planting to felling, and most forests are operated on a small scale. Such small forests

have low productivity, and may have a variety of business structures. In such cases,

it is difficult to increase the interest of investors in an area, increase cooperation

between dealers, and construct an effective production system.

The history of forestry studies in Japan can be classified into three periods. Early

studies were of individual forest owners ; the second period involved studies of the

function and characteristics of the forestry owners association, while the third period

involved studies of log production dealers and sawing dealers. The studies of

individ-ual forest owners were published in the first halt of the 1960s when family forest

management, which was active in increasing afforestation, was investigated. Kamino

(1962), Akabane (1978), Funakoshi (1993) examined individual forest owners within the

context of the 'polarization of farmers' theory, and discussed the merits and pitfalls of

capitalistic development. In addition, the study that examined characters and

prob-lems looked into family operation and their combination of agriculture and forestry

was performed. For example, Kira (1989) documented that the survival of family

forestry operations was supported by capital improvements achieved by diversifying

into both agriculture and forestry, and forest road maintenance and processing of

small volumes of logs by the forest owner's association. In addition, Kooroki (1996)

demonstrated that individual forest owners with forests of 50-100 ha were able to

survive with reinvestment from the outside of the forestry itself.

However, such areas are few in Japan, and in terms of forest administration, a

working party of the forest owner's association is the principal manager in many areas

(Takano and Arai, 2002). Prior to World War II the forest owners association was

controlled by the national government. Early studies were therefore interested in the

ideal organization of the forest owners association, while, an increasing number of

association, and attach great importance to this role in rural areas. For example,

Shiga (1995) compared a Japanese forestry owners association with a European

forestry owners association, and noted that the former forest owners association is

primarily a caretaker of forest policy, but does not have a background in the

produc-tion and marketing of timber as is the case in North Europe. The Japanese

associa-tions also do not have policy in terms of the collegial organization of forest owners ;

forests are generally small-scale and based on family labor, as also appears to be the

case in Europe. Shiga (1995) concluded that the Japanese forest owners association is

a "forestry contract capital", intermediate in character between the systems of West

Europe and North Europe. Takano and Arai (2002) emphasize that forest owner's

associations can progress significantly by diversifying contracts between forestry and

public service, participating in tourism organizations and other modernizing

initia-tives. Although, such characteristics are considered to be similar for log production

dealers') and sawing dealers2), there are few studies on log production dealers and

sawing dealers. Ando (1978) documented the progress of a large-scale dealer in

pulpwood production in Hokkaido and a small-scale dealer in Gifu prefecture.

Kitagawa (1984) noted that except for dealers in Hokkaido, log production dealers are

unable to become independent companies.

Many studies of individual forest owners, forest owner's associations, log

produc-tion dealers and sawing dealers emphasize that until now, Japanese forestry policy has

not considered regional differences, and timber imports have rapidly increased. In

terms of the individual forest owner, the position as land holder is strong in areas other

than South-Kyushu District, although the forest owners association has failed to meet

the expectations in terms of environment and industry. The capitalist development of

log production dealers is difficult in all areas except for those that contain many

national forests. However, as with the "Valley Control System" that the Forestry

Agency started to promote in 1992, the systematization of forestry remains a problem.

Meanwhile, individual forest owners, forest owner's associations, and log production

dealers have been examined separately, in a conventional way. In addition, there are

few studies on sawing dealers. Therefore little is known on the reality of

relation-ships among different actors on which to form a basis for systematization.

To address this problem, in this study we clarify changes in the current

organiza-tion of forestry businesses, log producorganiza-tion dealers, sawing dealers who are the initial

wood consumer, and regional forestry production systems. This report is based on the

data from the Okukuji area of Fukushima prefecture, Tohoku district, Japan (Figure

1). We selected this area because it has experienced production center formation

since the 1970s, and has seen increasing numbers of lumber markets, sawing dealers,

and log production dealers. The area is small in terms of the size of the area assigned

4 Ryohei SEKINE and Kouta MIROKUJI

0

To Shirakawa

1o\\1"Ii7--',. 1

Mt.„amiz`N.

1 i....A,4\.(

?

. r

N' Tanagura '

Machir... )

.

/

1 '...i

.-. ...„....,!

,

Boundaries of administrative \ (--- National roadl..---.Town or Village office To Mito Fukushima Prefecture To Sukagawa awa Sain ° V \ Mura To Ono Sametawa Mura X Hanawa Machi ( . amatsuri/

Mach/

To Iwaki 0Km , Fig. 1 To Mito Location of Okukuji areabetween private and national forests because the proportion of national and private

forest in most areas resembles that of the Tohoku District. That is to say, this study

can address these subjects collectively. We undertake this study to (i) investigate

trends in Japanese forestry, (ii) investigate changes in forestry policy considered in the

Okukuji area and related regional action, (iii) investigate changes in the distribution of

logs and timber, and (iv) document the current situation regarding log production

dealers and sawing dealers.

2. Changes in postwar forestry and its characteristics in the Tohoku district

Prior to World War II, forests in Japan were used for mowing and fuel collection3).

The main purpose of forest policy was the sustainable use of the forest. Destructive

tree felling began following World War II. Wood was required for use as mine timber

and for reconstruction following war damage. In response to this demand, the

Forestry Planning System was introduced in 1951 to ensure sound forestry practices.

The Forest Law was enforced in the same year, and was concerned with cooperative

organization of the forest owners associations.

From the early 1970s, rapid economic growth saw the advent of expansive

afforestation to meet high demand for quality timber. In Japan, the price of Japanese

while the volume of domestic log production decreased from 43,250,000 m3 in 1960 to

42,990,000 m3 in 1970 because many logs reached maturity at this time. Augmentation

of timber serviceability became an urgent policy agenda, and a nationwide change

occurred from natural forest to plantation plantings of Japanese Cedar, Hinoki

Cypress (Chamaecyparis obtusa) and Japanese larch (Larix leptolepis). At that time,

individual small to medium sized family forest owners led the forestry sector. The

First Forestry Structure Improvement Project (1964-1971) started with the Basic Law

of Forestry promulgation of 1964, promoting expansion of the management foundation

of individually owners of small to medium sized forests, income gap correction among

industries, modernization of the forest and field of physical structure, maintenance of

forest roads, and the mechanization of forestry. Management of the national forests,

which provided the base funding for these projects, was of a high standard at this time.

Therefore a large amount of surplus funds were allotted to the construction of forest

roads and the substantiality of machinery and equipment. From 1959 to 1968, the

national general account allocated a total of 42 billions yen to such projects.

Meanwhile, imported logs increased to 43,030,000 m3 in 1970, slightly more than the

volume of domestic log production. Problems in the industry began to surface at this

time, including rapidly increasing labor costs for afforestation projects.

From the 1970s, Japanese forestry followed a course of decline with the slowed

growth of the Japanese economy. Until 1990 and the height of the bubble economy,

demand for logs changed at around 100,000,000 m3 per year, but this demand was

mainly for pulp tip material. Demand for sawed timber decreased, and the volume of

domestic timber production fell by large quantities in the face of imports of cheap

foreign timber products. In addition, afforestation rates of 350,000 ha in 1970

de-creased to 60,000 ha by 1990 due to a decrease in the availability of suitable land and

rapid rises in expenses. The forestry sector thus failed to become more responsive to

change after the 1970s oil crisis. Furthermore, for individual forest owners officially

defined as the leaders of forestry during the 1960s, the availability of affordable labor

decreased throughout the country due to income gap and aging.

The forestry industry was reconsidered in the Second Forestry Structure

Improve-ment Project (from 1972 to 1979), and this placed the forest owners association as a

new leader in forest management under the terms of a joint enterprise. Programs

were undertaken to integrate log production, milling and the sale of timber. Such

projects included the Second Forestry Structure Improvement Project, the Third

Forestry Structure Improvement Project (from 1980 to 1990), and the Fourth Forestry

Structure Improvement Project (from 1990 to 1995). These projects were designed to

counter the mass importation of foreign timber products. The 1980s saw the

estab-lishment of a log market and saw mills by the forest owners associations, the abolition

6 Ryohei SEKINE and Kouta MIROKUJI

place. Meanwhile, afforestation continued, and at the end of 1989, the national forest

project had outstanding obligations of 2 trillions yen, with an accumulated deficit of 850

billions yen.

A remarkable fall in demand for timber accompanied the economic recession

following the bubble economy of the 1990s. The price of timber, which had been

maintained during prosperity, fell dramatically, especially for sawed timber. In

addition, the importing of raw timber was replaced by the importation of

manufactur-ed timber products such as laminatmanufactur-ed wood. The price of Japanese Cedar halved from

14,595 yen/m3 in 1990 to 7,794 yen/m3 in 1999, a remarkable decline. In reaction to

this situation, The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan (2001)

pointed out that "It is the situation that we can not expect that maintenance of the

forest advances by proprietary initiative of the forest".

Facing such an impending crisis for the Japanese forestry, the Valley Control

System (VCS) was promoted to stimulate the formation of production centers for

domestic lumber in 1992. VCS is based on Forest Law revised in 1991. VCS

nation-wide defined 158 forest planning areas as Valleys, and organized to realize forest

maintenance and low cost stability of domestic lumber within a local government.

This policy changed the operational unit of the policy to a wide Valley from

conven-tional local governments, at various levels. The VCS aims to manage the distribution

of timber and establish unity in the leadership of different localities. The VCS

achieved the above goals within its first ten years of existence. The forest policy

involved a shift in emphasis from the expansion of timber production to the significant

concerns of common welfare. A reality of the situation was more accumulated debt

of the national forest project of 3.8 trillions yen (1998).

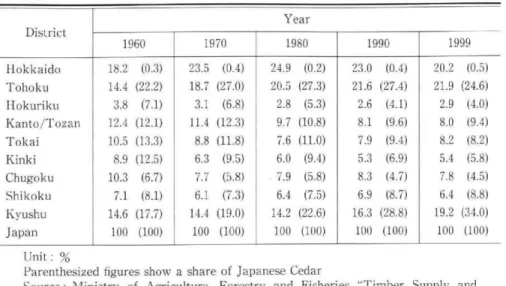

The recent state of forests and leaders of forestry in the Tohoku District,

northeastern Japan, are as follows (Table 1). In 2000, Tohoku District contains 19%

of the forested areas in the entire country. Artificial plantations comprise 38% of

these forests, of which 65% are covered with Japanese Cedar. Meanwhile, 43% are

national forests, and 46% are private forests. The Tohoku District is characterized

by large areas of natural forests, and large amount of Japanese Cedar in plantation

forests. Table 2 shows the number of the log production dealers, volume of

produc-tion/marketing per dealer, number of employees per dealer, and the nationwide share

of ownership of high-performance forestry machinery. A high proportion of

individ-ual forest owners in the District, carry out their own weeding and brushing, cleaning

cutting, climber cutting, and pruning. Afforestation work is relatively active in the

District. In contrast, forestry in Hokkaido is characterized by log production by a

small number of large-scale operators. Meanwhile, the Tohoku and Kyushu are

leaders in terms of the number of log production dealers with high-performance

Table 1 Changes of a quantity of timber production share in Japan

District Hokkaido Tohoku Hokuriku Kanto/Tozan Tokai Kinki Chugoku Shikoku Kyushu Japan Year 1960 18.2 14.4 3.8 12.4 10.5 8.9 10.3 7.1 14.6 100 (0.3) (22.2) (7.1) (12.1) (13.3) (12.5) (6.7) (8.1) (17.7) (100) 1970 23.5 (0.4) 18.7 (27.0) 3.1 (6.8) 11.4 (12.3) 8.8 (11.8) 6.3 (9.5) 7.7 (5.8) 6.1 (7.3) 14.4 (19.0) 100 (100) 1980 24.9 20.5 2.8 9.7 7.6 6.0 7.9 6.4 14.2 100 (0.2) (27.3) (5.3) (10.8) (11.0) (9.4) (5.8) (7.5) (22.6) (100) 1990 23.0 (0.4) 21.6 (27.4) 2.6 (4.1) 8.1 (9.6) 7.9 (9.4) 5.3 (6.9) 8.3 (4.7) 6.9 (8.7) 16.3 (28.8) 100 (100) 1999 20.2 21.9 2.9 8.0 8.2 5.4 7.8 6.4 19.2 100 (0.5) (24.6) (4.0) (9.4) (8.2) (5.8) (4.5) (8.8) (34.0) (100) Unit :

Parenthesized figures show a share of Japanese Cedar

Source : Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries "Timber Supply and Demand Report"

Table 2 General condition of log production dealer according to a district in Japan (2001)

District Hokkaido Tohoku Hokuriku Kanto/Tozan Tokai Kinki Chugokuinki Shikoku Kyushu Japan Number of Dealers 429 1,166 300 647 535 555 652 318 1,135 5,738 Volume per Dealer (m3) 6,402 2,722 1,092 1,886 1,549 1,115 1,354 2,336 2,528 2,338 Volume per Day(m3) 5.2 3.4 2.6 3.0 2.2 2.4 2.3 2.7 3.3 3.2 Member of Employee per Dealer Regular Employment 7.8 5.1 3.3 3.9 4.9 2.6 3.2 3.1 2.4 3.8 Temporary Employment 5.8 3.6 2.3 3.5 2.3 3.2 5.2 3.1 3.1 3.6 Share of Possession of a High-performance Machine* 12.5 18.3 8.3 8.3 6.7 9.2 11.7 3.3 21.7 100.0

*Share that assumed possession number of the whole country 100.

Source : Department of Statistical Information, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries

share in log volume, especially handling a lot of Japanese Cedar, although rates of

growth are small because of decreased felling within national forests (see Table 1). In

conclusion, Hokkaido has many national forests, although its pine volume has

8 Ryohei SEKINE and Kouta MIROKU JI

national forestry, mainly Japanese Cedar, and in the 1990s overtook Tohoku District

as the leading forestry area in Japan. Tohoku District remains the national leader,

but its production continues to stagnate.

3. Profile of the Okukuji area

The Okukuji area is located in Higashishirakawa Gun at the southern margin of

Fukushima Prefecture, and comprises Tanagura-Machi, Yamatsuri-Machi,

Hanawa-Machi, and Samegawa-Mura (Figure 1), as defined by the VCS. The Abukuma

Mountains rise in the eastern part of the area, and Yamizo Mountains rise in the

western part ; the Kuji River flows southward through the center of the area. The

population of the Okukuji area was 53,587 in 1960, but decreased markedly by the first

halt of the 1970s, with a population of 39,341 in 2000. The Primary industry was the

largest employer until 1980, but by 1985 more people were employed in secondary and

tertiary industries. The numbers of those employed in forestry has changed over time

in the following trend : 991 (1960), 520 (1965), 403 (1970), 376 (1975), 414 (1980), 357 (1985),

312 (1995), 324 (2000)4). The numbers, as a percentage of the labor force, fell from 4%

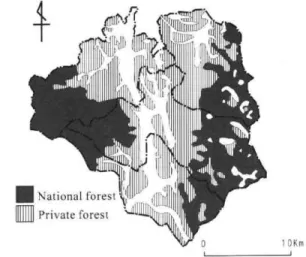

in 1960 to 2% in 1995. Forests make up 78% of total land area in the Okukuji area,

with plantation forests 66% (1995). The dominant timbers are Japanese Cedar, with

51%, Hinoki Cypress with 10%, and Japanese Red Pine (Pinus densiflora) and Japanese

black pine (Pinus thunbergii) with 5%. National forests make up 43% of the forests,

while 55% are in private ownership. The national forests are distributed largely in

areas of higher elevation, while forest under private ownership is generally located

close to settlements (Figure 2). Forests under individual ownership in the Okukuji

area average 6 ha in size, which is small-scale. Forestry production has stagnated in

recent years. In 2000, the number of individual forest owners holding forests of more

than 1 ha in area was 2,627. Of these forests, 66% were less than 5 ha in area. For

individual forest owners with more than 3 ha of forest, only 8% sold timber, which is

an extremely small proportion.

Afforestation of the Okukuji area began during the Edo era, but, full-scale

afforestation only took hold following World War II. The Okukuji area is

tradition-ally a leading production area of Japanese Cedar, and generally has a short rotation

of 30-35 years. Forests in the Okukuji area are mainly distributed over the Yamizo

and Abukuma mountains. Afforestation was intense in the Yamizo Mountains, where

growth conditions are good, and the Okukuji Forestry Promotion Task Force was

established in 1969 with the aim of producing high quality timber products in response

to increased competition from imported timber. This organization enforced pruning

and thinning on individual forest owners, established the sawmill that promoted the use

4— guINSI?irrg"::.101Pip

('`

.,llf1111111111II

i

T11191111

1''liI6

11111

_ii1111b

1(11'1'111;111'

im...ffilli

+I 11 , I, 1

'11I,4lif11111

1 I I

1111111'l•

Illb iir,...iive

111

•

4 "I1pl41111

ill

41;

h

111

' ; lbI4'

"1111;Ir1

1111'1°111'1ll1'6r4

I)it6

II.National

forest'tilli111111111P

ji

[ Private

forest ""1111

IIII

I1

I1

0

1

0Km

Fig. 2 Distribution of a national forest and a private forest in Okukuji area

products.

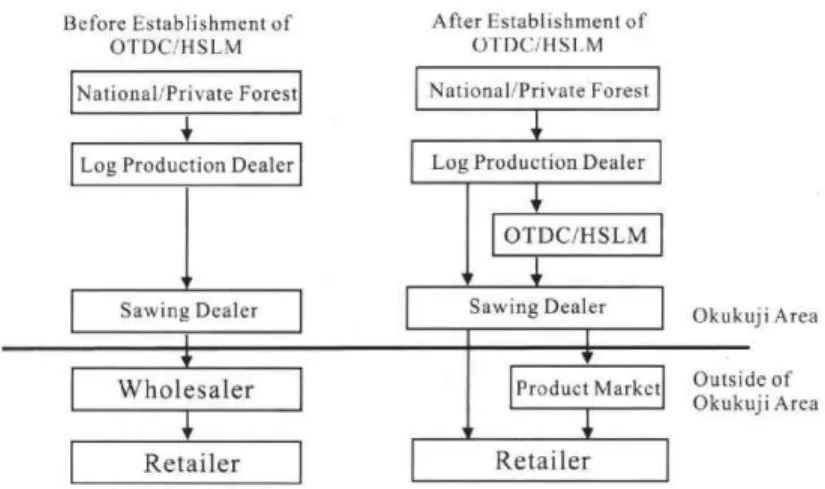

In addition, the Okukuji Timber Distribution Center (OTDC) was established as a

log market in 1984, with a goal of the stable marketing of timber (Figure 3). The

OTDC has the greatest share of the log market in the area. In the Okukuji area, the

Higashi Shirakawa Sawing Cooperative (HSSC) formed from an existing sawing

dealer cooperative. HSSC has a commercial function, and traded in surplus wood,

although there trading volume was small. Before establishment of the OTDC, direct

dealing with log production dealers and sawing dealers was common. Sawing dealers

were affiliated to log production dealers ; sawing dealers purchased logs, and log

production dealers undertook the sawing. The timber produced by sawing dealers

was sent to retail stores in Fukushima prefecture and Kanto district via wholesalers.

In the golden age of the 1960s, approximately 60 sawing dealers were established in the

area. However, the industry was transformed by the circulation system and the

slump in demand for domestic lumber from the 1970s. The sawing dealers that had

sawed all available logs changed to sawing logs on demand, and sawing dealers

specialized in the production of component materials such a pillar and an board. For

specialized sawing dealers, direct dealing with log production dealers became a

problem. Sawing dealers had to buy unnecessary logs, and the sale of surplus logs was

difficult. In addition, thinning of Japanese Cedar trees planted in the 1950s was

necessary in the Okukuji area, and the use of thinning materials became stagnant.

The Okukuji Valley Forestry Activation Center was established in 1991 by the

VCS, and further expansion of market functions was planned. In addition, the log

10 Ryohei SEKINE and Kouta MIROKUJI

Before Establishment of OTDC/HSLM National/Private Forest

Log Production Dealer

Sawing Dealer

After Establishment of OTDC/HSLM National/Private Forest

Log Production Dealer

OTDC/HSLM

Sawing Dealer Okukuji Area

Wholesaler

J

Product

Market

OkukujiOutside

of

AreaRetailer Retailer

Fig. 3 Systems from production to destination of timber in Okukuji area Source : field study in 2001

(HSLM) in 1985. Log sales of the OTDC and HSLM established by the processes

outlined above show consistent increases. As evident in Table 3, log sales of the

OTDC rose from 23,928 m3 in 1988 to 51,984 m3 in 1999. Log sales dropped to 41,901 m3 in 2000, but, according to the hearing for OTDC, increased again in 2001. The log

Table 3 Volumes of log in OTDC, HSLM

OTDC Year Volume (m3) 1988 23,928 1989 32,569 1990 36,382 1991 36,382 1992 41,194 HSLM 1993 43,280 1994 42,760 Year Volume (m3) 1995 41,260 1995 13,523 1996 47,789 1996 13,756 1997 47,539 1997 13,334 1998 51,488 1998 9,881 1999 51,984 1999 14,145 2000 41,901 2000 15,800

Count period of OTDC ; from April to March of the next year Count period of HSLM ; from October to September of the next year

OTDC (Destination)

OTDC (Supply)

HSLM (Destination) HSLM (Supply) 0 10 20 30 40^ Okukuji area

Fukushima Prefecture except Okukuji area

^ Outside of Fukushima Prefecture

Fig. 4 Volume of transactions in OTDC, HSLM

The data of OTDC is in 2000

The data of HSLM is in 1999 Source : OTDC, HSLM

sales of HSLM decreased from October 1997 to September 1998, bi

increased since 1995. The main log handled by OTDC and HSLM jE and as with most Japanese Cedar, logs are received by local log pr

Figure 4 shows the supply and destination of logs of the OTDC a

OTDC handles 86% Japanese Cedar, 10% Hinoki Cypress, and 3% ja Logs supplied to the OTDC are 79% from within the Okukuji area,

areas within Fukushin prefecture, and 9% from outside of the

destinations of OTDC logs are 33% to the Okukuji area, 28% t^

Fukushima prefecture, 28% to Tochigi prefecture, and 10% to Ib

Logs supplied to HSLM are dominantly from the Okukuji area (859

other parts of Fukushima prefecture and 13% outside of Fukushim

terms of the destination of HSLM logs, 70% go to the Okukuji area, 1,

within Fukushima prefecture, and 17% outside of Fukushima pr(

ships more logs than OTDC within the Okukuji area. That is to sa

ability to distribute logsoutsideofthearea,whileHSLMdistribute:

5033 1 0Ill

sedfromOctober1997toSeptember1998,but have generally

ThemainloghandledbyOTDCandHSLMisJapanese Cedar,

.neseCedar,logsarereceivedbylocallog production dealers.

pplyanddestinationoflogsoftheOTDC and HSLM. The

paneseCedar,10%HinokiCypress,and3% Japanese Red Pine.

1TDCare79%fromwithintheOkukujiarea, 12% from other

naprefecture,and9%fromoutsideoftheprefecture. The

logsare33%totheOkukujiarea,28%toother areas of

28%toTochigiprefecture,and10%to Ibaraki prefecture.

VIaredominantlyfromtheOkukujiarea (85%), with 2% from

maprefectureand13%outsideof Fukushima prefecture. In

ofHSLMlogs,70%gototheOkukujiarea, 4% to other areas

lecture,and17%outsideofFukushima prefecture. HSLM

1TDCwithintheOkukujiarea.Thatisto say, OTDC has the

log outside of the area, while HSLM distributes log to precincts.

4. Current forms of log production dealers

12 Ryohei SEKINE and Kouta MIROKUJI

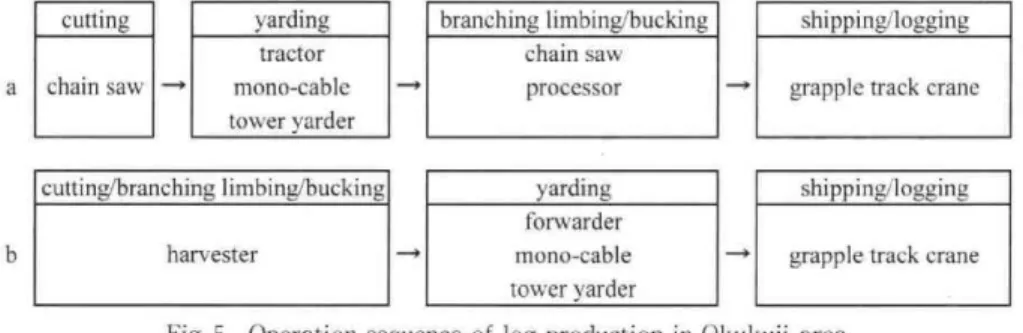

standing crop and work on pruning, bucking and yarding. Figure 5 shows a system of

log production common in the Okukuji area. Standing crop is sent to the wood yard

after being felled, and branching limbing5' and buckine are undertaken. A chainsaw

is used for cutting. Logs are taken to the wood yard by ground skidding by a

forwarder or mono-cable tower yarder. Branching limbing and bucking are usually

performed with a chainsaw, but in recent years a processor is also used. Log

produc-tion dealers who own harvesters undertake those processes at the site of felling. Logs

are then forwarded to the wood yard. Collected logs are carried to market or sawmill

by grapple track crane.

In 2000, there were 61 log production dealers in the Okukuji area, mostly private

enterprises. Many were family businesses, and many stopped operating by 2001.

There were currently 23 dealer companies active in 2001. In this study we

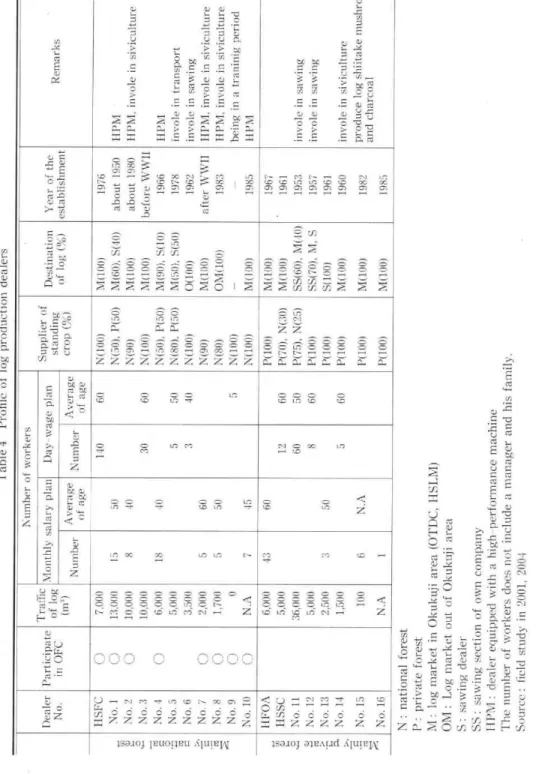

investigat-ed 19 of these 23 cases (Table 4). Dealers with large numbers of employees are

generally unionized. Thirteen of the 19 dealers employ less than nine people staff.

Most dealers handle wood seed of Japanese Cedar.

We first describe the log production dealers who work largely with national

forests. National forests in the Okukuji area are under the jurisdiction of the

Tanagura District Forest Office. Silviculture of national forests is enforced by

con-tract, and cutting is allocated with the sale of standing crop. Since 1990, the District

Forest Office ceased organizing cutting, and the Okukuji Forestry Cooperative (OFC)

undertakes all silviculture and cutting. In 2001, the District Forest Office carried out

the following work : planting of 30 ha, weeding and brushing of 277 ha, climber cutting

of 141 ha, cleaning cutting of 31 ha, regeneration cutting of 15,672 ha, and thinning of

267 ha. Some of the logs produced by regeneration cutting and thinning are sold at

auction by the sawing dealer after drying the stem without limbing ;8' remaining logs

are shipped by the OTDC. In addition, there is a negotiated contract termed

system-atic sales, and one dealer in the Okukuji area negotiated a contract for five years from

a cutting chain saw •^1 yarding tractor mono-cable tower yarder branching limbing/bucking chain saw processor •^). b shipping/logging

grapple track crane

cutting/branching limbing/bucking harvester yarding forwarder mono-cable tower yarder shipping/logging

grapple track crane

Fig. 5 Operation sequence of log production in Okukuji area "a" does not use harvester

, "b" use harvester. Source : field study in 2001, 2004

Table 4 Profile of log production dealers a a a C a co co 0 a a C • *C-7, a

Dealer No. HSFC No.

1 No. 2 No. 3 No. 4 No. 5 No. 6 No. 7 No. 8 No. 9 No. 10 HFOA HSSC No. 11 No. 12 No. 13 No. 14 No. 15 No. 16 Participate in OFC 0 0 C C C Traffic of log (m3) 7,000 13,000 10,000 10,000 6,000 5,000 3,500 2,000 1,700 0 N.A 6,000 5,000 36,000 5,000 2,500 1,500 100 N.A Number of workers Monthly salary plan Number 15 8 18 5 5 7 43 3 6 Average of age 50 40 40 60 50 45 60 50 N.A Day wage plan Number 140 30 5 3 12 60 8 5 Average of age 60 60 50 40 5 60 50 60 60 Supplier of standing crop (%) N(100) N(50), P(50) N(90) N(100) N(50), P(50) N(80), P(50) N(100) N(90) N(80) N(100) N(100) P(100) P(70), N(30) P(75), N(25) P(100) P(I00) P(I00) P(100) P(100) Destination of log (%) M(100) M(60), S(40) M(100) M(100) M(90), S(10) M(50), S(50) 0(100) M(100) OM(100) M(100) M(100) M(100) SS(60), M(40) SS(70), M, S S(100) M(100) M(100) M(100) Year of the establishment 1976 about 1950 about 1980 before WWII 1966 1978 1962 after WWII 1983 1985 1967 1961 1953 1957 1961 1960 1982 1985 Remarks HPM HPM, invole in siviculture IIPM invole in transport invole in sawing HPM, invole in siviculture HPM, invole in siviculture being in a traninig period HPM invole in sawing invole in sawing invole in siviculture produce log shiitake mushroom and charcoal N : national forest P : private forest M : log market in Okukuji area (OTDC, HSLM) OM : Log market out of Okukuji area S : sawing dealer SS : sawing section of own company HPM : dealer equipped with a high-performance machine The number of workers does not include a manager and his family . Source : field study in 2001, 2004

14 Ryohei SEKINE and Kouta MIROKUJI

2001.

The OFC was formed as an organization to undertake projects within intratubal

national forests of the District Forest Office in 2001. The Higashi Shirakawa Forestry

Cooperative (HSFC) and six dealers (No. 1, 2, 4, 7, 8, 9) participate in these projects.

The HSFC formed in 1976, and current union membership was 51 in 2001. The

number of workers within HSFC is 140, and working units are organized for each of

the 26 settlements in the Okukuji area. The average age of workers is in the 60s.

The OFC was established to transfer contract labor dealers, with whom the District

Forest Office traditionally worked, to private enterprises. The purpose was to

effectively promote projects within national forests. The OFC now carries out all the

intratubal work of the District Forest Office. Six dealers participating in OFC's own

high-performance equipment, except dealer No. 9. Dealer No. 4 was the first to adopt

high-performance mechanization, and introduced a harvester and a processor in 1993.

Dealer No. 4 was founded in 1966, and became a limited liability company in 1985.

This dealership employs 18 forestry workers, an office worker, and six executives.

The average age of workers is in the 40s, and the youngest worker is 20 years old.

Although Dealer No. 4 has made contract work from the District Forest Office its core

business since it was founded, with decreasing operations of the District Forest Office,

contracts from the District Forest Office now make up just 70% of its business. In

recent years, dealer No. 4 has purchased standing crop of a national forest in

Iwaki-Shi and a private forest in the Okukuji area. The volume of produced logs is

approximately 6,000 m3 per year, and 90% are shipped by OTDC. The

high-perfor-mance mechanization of other dealers occurred during the second half of the 1990s.

Dealer No. 8 is the log production dealer who performs afforestation work within

national forests. The dealership has three family members as managers and five other

employees. The average age of employees is in the 50s. One of the conditions for

joining the OFC is accession to authorize of a prefecture ; Dealer No. 8 introduced

high-performance equipment to satisfy these conditions. Dealer No. 8 buys standing

crop within a national forest to make effective use of their high-performance

equip-ment. Additional logs are gained from private forest. Dealer No. 8 does not ship

logs via OTDC, as it considers that markets except outside the Okukuji area are

advantageous. The characteristics of the four other dealers participating in the OFC

are as follows. Dealers No. 2 and 7 perform afforestation work. The former

receives a contract of the core business, while the latter undertakes the purchase of

standing crop. Dealer No. 7 has always regarded national forests as the core of their

business. In contrast, Dealer No. 2 formerly conducted half of its business in private

forests, currently shifting 90% of its business to national forests. It is currently

difficult to gain stability of log supply solely from private forests. In addition, Dealer

opportu-nity in this area, the dealer can employ persons seeking employment . Dealers No. 2 and 7 ship produced logs via OTDC and HSLM.

Dealer No. 1 manages equal business in both national and private forests , and has a long history in the Okukuji area, having been established in the 1950s. Dealer No.

1 has an authorized customer in Tochigi prefecture , and employs 15 workers. The

average age of workers is in the 50s, and the youngest worker is 35 years old . The

dealer purchases 13,000 m3 of standing crop per year, with 60% of logs going to OTDC

and HSLM, and 40% to a sawing dealer in the Okukuji area. Dealer No . 9 was

established in 2003, having been in a training period until then due to inexperience of

staff.

The four dealers describing next do not participate in the OFC, but purchase

standing crop within national forests as there main activity. Of these four dealers ,

only No. 10 has adopted high-performance mechanization. Dealer No. 10 was

found-ed in 1985, and the manager was a worker at other log production dealers earlier . The

dealer currently employs seven workers, with an average age of 45 years, and the

youngest worker in his 20s. The dealer conducts business in national forests of the

Okukuji area and Iwaki-City, with 80% of produced logs shipped to OTDC and HSLM .

Dealers No. 3, 5, and 6 use subcontracted workers. Dealer No . 3 previously performed

sawing. In the golden age of the second half of the 1980s, log volumes were 50,000 m3,

however, during the 1990s his management declined . Therefore he settled a company

in 1997, and changed management system to private enterprise. Approximately 30

subcontracted workers are registered with the dealer, with an average of 10 people

actively engaged in work. His current specialty is national forests . Dealer No. 5

holds an additional business in transport, while No . 6 has business interests in the

sawing industry. As for the former, the Okukuji area is the main business area . In

terms of log sales, 50% go to sawing dealers in the Okukuji area. In contrast, the

latter mainly treats Hinoki Cypress. He performs business mainly with the Mito

District Forest Office, and all logs are manufactured in the sawing section of the

company.

The following section describes the log production dealers who concentrate in

private forests. Forestry activity during 2000 in private forests of the Okukuji area

is as follows. Area of planting was 25 ha, weeding and brushing 200 ha , cutting 126 ha,

and thinning 105 ha. As for the volume of logs, regeneration cutting was 12,000 m3,

thinning 59,000 m3, thus 71,000 m3 in total. Individual forest owners or the

Higashi-shirakawagun Forest Owners Association (HFOA) carries out afforestation work in

private forests. Individual forest owners entrusts HFOA with cutting work or sell to

log production dealers as standing crop of private forest. The HFOA was established

in 1967. In 2001, union membership of HFOA was 4,042 people. In addition, the

16 Ryohei SEKINE and Kouta MIROKUJI

HFOA organizes 13 working units. Workers are employed according to a day-wage

plan, and the average age of workers is in the 60s, while the youngest worker is in his 30s. There are differences in the number of days worked by employees, ranging from

100-250 days per year. Workers and working units hold forestry equipment such as

chainsaws ; the HFOA does not hold forestry equipment. The salary varies with

working detail and holding of forestry equipment. Annual income varies widely from

1,000,000 to 10,000,000 yen.

As evident in Figure 6, the business income of HFOA rose markedly during the 1970s, and reduced after the 1980s. Of the profit categories of Figure 6, "sale" means sale of logs and profit from the sale of sawing product, while "use" means profit from

contract work of public services such as afforestation, sterilization, and forestry

conservation. The profit ratio of "sale" in 1975 was 70.9%. However, in the 1980s the

value of "use" increased, from 11.9% in 1970 to 54.4% in 2000. This trend arose

because the current price of logs was low, and it was difficult to generate profit even

if an individual forest owner sold logs. Sales of logs in 2000 were approximately 6,000

700000 600000 = a.) ›, a a a st ) E o U C c, a.) C .... v) = 4 500000 400000 300000 200000 100000 0 19711 1975 1981) 1985 Year 1990 1995 2000

I-_-_] Sale . ' Purchase ^ Use ^ Finance/Guidance Fig. 6 Change of business income in HFOA

"Sale" means sales of timber and other products (an edible wild plant

, mushroom, charcoal, etc.)

"Purchase" means group purchase such as a young plant

, a pesticide and manure "Use" means establishment and maintenance of the forest (breeding

, prevention, and forest conservation) by the public works project and rental of machine

"Finance/Guidance" means representation of a loan procedure of public finance corporation fund and technical guidance to members of association

Source HFOA

m3. All logs produced by HFOA are shipped by OTDC. In the Okukuji area, the

Higashi Shirakawa Sawing Cooperative (HSSC) is involved in log production, made up

of 26 sawing dealers within the Okukuji area. The HSSC employs 12 people in the log

production division, with an average age of 60 years. HSSC was established in 1961,

and initially regarded national forest as core business. Since 1984, however, HSSC

undertook log production in private forest, and enlarged the scope of business in

Tochigi and Ibaraki prefectures. Log volume in 2000 was approximately 5,000 m3,

with a market share in the Okukuji area of 20.7%. HSSC purchases logs from

individual forest owners in the Okukuji area and Tochigi and Ibaraki prefectures .

Once the purchase contract is concluded, workers from the log production division

undertake log production.

The description now turns to the log production dealers who deal mainly with

private forest, and are not part of a cooperative (Table 4). Dealer No. 11 employs 60

workers, and in the past has focused on national forests as a business objective.

However, due to the decrease in log resources within national forests, he shifted

business objectives to forest under private ownership. The volume of logs was 36,000

m3 per year, with 25% from national forests and 75% from private forests. The

Okukuji area makes up 10% of log production, with 90% in Ibaraki prefecture. Of

produced logs, 60% are processed in the sawing section of the company. The

remain-ing 40% are shipped to OTDC and HSLM. Dealer No. 12 also has a sawing section,

which was established in 2001. Dealer No. 12 employs eight workers in log

produc-tion, with an average age of 60 years. The scope of business is limited to the Okukuji

area. The dealer uses 70% of its produced logs, with the remainder shipped to OTDC,

HSLM or directly to sawing dealers. Dealer No. 13 works only in private forests, and

is involved in specialized log production. He employs three staff. Ten years ago the

dealer worked with national forests, but switched to private forest as the quality of

timber from national forests declined. He seeks profit by shipping logs directly to

sawing dealers in Tochigi prefecture. In contrast, Dealers No. 14 and 16 work only

with private forest and send logs to OTDC and HSLM. Meanwhile, Dealer No. 15

produces bed logs for growing shiitake mushroom and wood for charcoal production.

His business objective is mainly hardwood, and the volume of logs of Japanese Cedar

is approximately 100 m3 per year.

5. Current form of sawing dealers

This chapter describes sawing dealers in the Okukuji area. Sawing involves

cutting boards and squared lumber from a log. Sawing dealers are equipped with

band saws, circular saws, and gang saws, of which the band saw is most important. In

18 Ryohei SEKINE and Kouta MIROKUJI

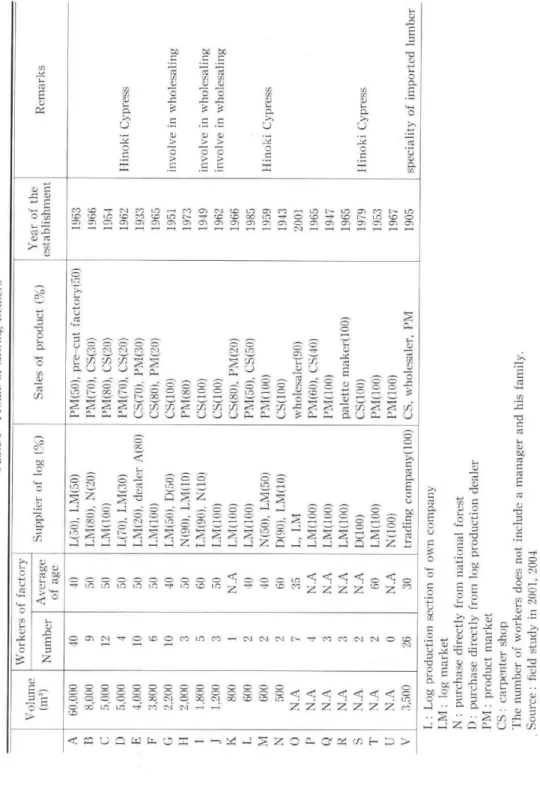

As evident in Table 5, 21 dealers, all except dealer V, specialize in domestic

lumber. In addition, 18 dealers specialize in Japanese Cedar. Dealers D and M make

a specialty of Hinoki Cypress, and V makes a specialty of imported lumber. Dealer

A is a sawing dealer of domestic lumber with great volumes on a national scale.

Dealer A employs 60 staff, and log consumption is approximately 60,000 m3 per year.

Dealer A was founded as a log production dealer in 1953, and began sawing Japanese

Red Pine and Hinoki Cypress from 1963. However, Japanese Red Pine suffered

damage from pine bark beetles, and resources of Hinoki Cypress have decreased,

prompting a switch to Japanese Cedar in 1989. Another reason for this change was an

increase in the price of American hemlock (Tsuga sieboldii), which was a rival of a

domestic Japanese Cedar. In addition, most of the Japanese Cedar in the Okukuji

area matured at this time. Dealer A sells 50% of product in the Tohoku region, and

the remainder in the Kanto District : a pre-cut factory is 50%. Dried wood is the

main product of Dealer A. Dried wood involves natural seasoning for a period of two

or three months after drying the stem without limbing. In this way, Dealer A is able

to produce dried wood with less than 25% water content.

Dealers G, I, and J, are also involved in wholesaling. Dealer G initially specialized

in sawing when first established in 1951, Profits in the sawing industry declined in the second half of the 1970s, thus prompting the dealer to become involved in wholesaling.

He employs 23 staff, with 10 working at saw mill. The destination of product is

carpenter shops in the Okukuji area, which number over 300. Dealers G and I initially

specialized in sawing, with the latter established in 1949. Since the second half of the

1960s, Dealer I has been involved in wholesaling. He employs nine staff, with five

working at saw mill, sourcing logs from OTDC and HSLM. The destination of its

products is approximately 100 carpenter shops. Dealer J is also involved in

wholesa-ling, and employs nine staff, of whom three are saw mill workers.

We now pay attention to dealers who specialize in the sawing industry. Dealers

B, C, H, P, Q, T, and U specialize in the product market. Dealers B, C, P, Q, and T

source logs from OTDC and HSLM and outside the local market. Dealers H and S

sources logs from the District Forest Office. Dealers B and C are the two largest of

these sawing dealers. They produce pillars professionally. Dealer B employs nine

staff, while dealer C employs 12. Dealer B sends 70% of its product to Tokyo. The

remainder is sent to carpenters shops in Shirakawa-City and Sukagawa-City. For

Dealer C, 80% of its product market is in Tokyo and Saitama prefecture.

Dealers P, Q, and T are family businesses. The number of employees in Dealer

P is four, with three in Q and two in T. These dealers source logs from OTDC and

HSLM. Dealer P mainly purchases mid-quality logs, while T mainly purchases small

logs. The primary destinations of products from these dealers are Ibaraki and

Table 5 Profile of sawing Dealers A B C D E F G II J K L M N 0 P Q R T U V Volume (m3) 60,000

8,000 5,000 5,000 4,000 3,800 2,200 2,000 1,800 1,200 800 600 600 500 N.A N.A N.A N.A N.A N,A N.A 3,500

Workers of factory Number 40 9 12 4 10 6 10 3 5 3 1 2 2 2 7 4 3 3 2 2 0 26 Average of age 40 50 50 50

50 50 40 50 60 50 N.A 40 40 60 35 N.A N.A N.A N.A 60 N.A 30

Supplier of log (%) L(50), LM(50) LM(80), N(20) LM(100) L(70), LM(30) LM(20), dealer A(80) LM(100) LM(50), D(50) N(90), LM(10) LM(90), N(10) LM(100) LM(100) LM(100) N(50), LM(50) D(90), LM(10) L, LM LM(100) LM(100) LM(100) D(100) LM(100) N(100) trading company(100) Sales of product (%) PM(50), pre-cut factory(50) PM(70), CS(30) PM(80), CS(20) PM(70), CS(20) CS(70), PM(30) CS(80), PM(20) CS(100) PM(80) CS(100) CS(100) CS(80), PM(20) PM(50), CS(50) PM(100) CS(100) wholesaler(90) PM(60), CS(40) PM(100) palette maker(100) CS(100) PM(100) PM(100) CS, wholesaler, PM Year of the establishment 1963 1966 1954 1962 1933 1965 1951 1973 1949 1962 1966 1985 1959 1943 2001 1965 1947 1965 1979 1953 1967 1905 Remarks Hinoki Cypress involve in involve in involve in Hinoki Hinoki wholesaling wholesaling wholesaling

Cypress Cypress speciality of imported lumber L : Log production section of own company LM : log market N : purchase directly from national forest D: purchase directly from log production dealer PM : product market CS : carpenter shop The number of workers does not include a manager and his family . Source : field study in 2001, 2004 H C C

20 Ryohei SEKINE and Kouta MIROKUJI

As for Dealers H and U, the destination of their products is intermediate product

markets, with logs sourced by the purchase of standing crop within national forest. Dealers H and U are also family businesses, and mainly produce timber of a special use

called NONEITA and ROKUSHAKUZAI7). Both dealers source stock by the

pur-chase of standing crop from within national forests. As with dealers E, F, K, L, N,

and S, the destination of final product is carpenter shops. Dealers F, K, and L source

logs from OTDC and HSLM.

Dealers N and S source logs directly from log production dealers, while Dealer E sources logs from Dealer A. Dealers K, L, N, and S have small numbers of staff. Dealer E specializes in ROKUSHAKUZAI , with 70% of final product sent to carpenter

shops, and the remainder to product markets in Kanagawa and Gunma prefectures.

Dealer E ships directly to do-it-yourself stores, while Dealer F mainly produces pillars.

For Dealer F, 80% of final product is sent to carpenter shops, with 20% sent to product

markets in Ibaraki and Tochigi prefectures.

Dealers K, N, and S produce pillars and boards to order from carpenter shops.

These dealers purchase logs according to the demands of carpenter shops, and

pur-chase directly from the log production dealer. Dealer L ships 50% of product to a

single large carpenter shop in Fukushima prefecture. Dealer 0 is a sawing dealer that

began operation in 2001. Dealer 0 was initially a log production dealer, but obtained

the facilities of a sawing dealer who had discontinued its business. Dealer 0 employs

seven staff, with a young average age of 35 years old. Dealer R is a sawing dealer who

specializes in the production of board for palettes. All the products of Dealer R are

shipped to a palette maker.

We now turn to describe dealers who mainly produce Hinoki Cypress products.

Dealer D employs seven staff, while Dealer M employs two. These dealers mainly

handled Japanese Cedar until about 1980, however, they gradually switched to sawing

Hinoki Cypress because of a slump in demand for Japanese Cedar products. The

Okukuji area has only minor stands of Hinoki Cypress. Therefore these dealers

purchase logs from national forests outside of the Okukuji area, from all over the

eastern Japan. During 2000, Dealer M sourced Hinoki Cypress from Iwate and Aichi

prefectures.

Since 1988, Dealer V has mainly handled imported logs. The main business of

Dealer V is assembling timber for houses, and sawing to alter imported board and

pillar. Dealer V mainly handles hemlock produced in the U.S.A. pine and whitewood

(Chamaecyparis pisifera). The dealer employs 38 staff and sources timber from a

trading company in Iwaki-City ; the destination of its product is a major carpenter

6. Discussion

Log production dealers in the Okukuji area are divided into those with a business

focus on national forests and those with a focus on private forests. Log production

dealers who focus on national forests characteristically own high-performance

machines such as harvesters and processors. However, many dealers changed the

forest to aim at it. Both types of dealers have changed their business objectives since

their establishment. This has involved decreasing involvement with national forests

as other opportunities arose, although, different dealers reacted differently to new

situations. The location of forest resources influences management choice of log

production dealers. When resources are rare in the Okukuji area, as is the case for

Dealer No. 6, the dealer must be active outside the Okukuji area, but there are many

dealers who market logs to the Okukuji area. Log production dealers have expanded

their areas of operation to the North Kanto and Tohoku districts, and left the Okukuji

area. This tendency is strong for large-scale dealers with high-performance

machin-ery. Smaller dealers cope by specialization in the production of bed logs to produce

shiitake mushroom and by dealing directly with sawing dealers. As with large-scale

dealers, smaller dealers are active outside the Okukuji area. Dealer cannot be overly

concerned about the territories of the Valley Control System, which the Forestry

Agency established for the maintenance of management, as most seek

high-perfor-mance mechanical operation, and owing to a national budget deficit, the amount of

works in national forests has decreased. Each dealer must develop a business outside

the Okukuji area to raise the proportion of high-performance mechanical operations.

In addition, in private forests of the Okukuji area in particular, the desire of individual forest owners to increase production is reduced, and the Okukuji area has struggled to

supply orders for log production dealers. That is to say, an increase in forest

resources to match the demands of dealers is difficult in the Okukuji area, as is the

commercialization of existing forest resources.

For the HSFC, the aging of employees is remarkable, while log production dealers

seek to employ a young work force. The Okukuji area suffers from an outflow of

youth and a decrease in job opportunities, as with many rural areas in Japan. Log

production dealers provide job opportunities that are important in the Okukuji area.

There also exists the possibility for young workers to gain business promotion to new

log production dealership. It is necessary to maintain a system that supports such a

movement.

Changes have occurred in sawing dealers and log production dealers in response to

changes in the business scene. Until the 1980s, sawing dealers in the Okukuji area

mainly treated Japanese Cedar. However, a slump in demand for domestic lumber

22 Ryohei SEKINE and Kouta MIROKUJI

various actions to address declining returns. For example, dealers undertook

mechan-ical modernization, insured forward sales of a product, and switched from Japanese

Cedar to imported wood and Hinoki Cypress. The sawing dealers came to produce

the building materials which accepted a careful order of a customer. This tendency

is strong among smaller dealers. Many sawing dealers source logs from the binary

log market (OTDC, HSLM) in the Okukuji area, but some dealers source logs without

a predictable market. Such dealers cope with a customer order by direct and flexible

log purchases. They employ many staff in the age range of 20-30 years. Sawing

dealers are important as employers in the Okukuji area, too. However, more sawing

dealers are family businesses than is the case for log production dealers. Sawing

dealerships are an important sector that adds higher value to forestry products of the

Okukuji area. Sustained release insurance of sawing dealers of family-run operations

may be a problem of the Okukuji area. Expansion and reinforcement of the log

market in an area generally results in positive regional activity. However, as for the

dealers, a tendency corresponding to an individual resisted a change of market. The

themes of the Okukuji area are the monogenesis administration from the production

to sales that "Valley Control System" aims at and the consistency with original

corporate activity of dealers. In addition, as the government and the privately forest

owners are owners of the forest, the decline in timber serviceability in privately owned

forests, in particular, creates a serious bottleneck in the forestry sector.

7. Conclusions

This study described trends in forestry in the Okukuji area, as representative of

trends in Japanese forestry. We documented recent characteristic activities in

for-estry within the Okukuji area, and examined the characteristics of log production

dealers and sawing dealers, although we were unable to analyze the workforce of

individual dealers or the management of forestry by individual forest owners. These

issues will be addressed in future studies.

Acknowledgement

We wish to express our gratitude to Professor M. Hino at Tohoku University for making a number of helpful suggestions.

Notes

1) They produce logs on site in forests and yards.

3) This is to trim odd small trees as a source of firewood. 4) The source is World Agricultural and Forestry Census.

5) Branching limbing means to cut a branch from a trunk to finish as a log.

6) Bucking means to cut off a log to constant length based on quality (size, degree of curve, passage and corrosion).

7) NONEIA is timber to use for a ceiling, and ROKUSHAKUZAI is a pillar cut off to length used in a Japanese traditional house.

References

Akabane, T. (1978) : Minyu ringyo no teitai to sono kozo (Stagnation of Private Forest Business and the Structure). Ringyo Keizai Kenkyukai Kaiho, 93, p. 22-35. Ando, Y. (1978) : Keizai kiki no shinko to ringyo / sanson mondai (Progress of Economic

Crisis and the Issue of Forestry / Mountain Village). Ringyo Keizai Kenkyukai

Kaiho, 93, p. 2-12.

The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan (2001) Annual Report on Trends of Forest and forestry (Fiscal Year 2000). http://www.hakusyo.maff.go. iP/

Funakoshi, S. (1993) : Tenkanki no Tohoku Ringyo/Sanson (The Turning Point of Northeastern Forestry and Mountain Village). Norin Tokei Kyokai (Association

of Agriculture and Forestry Statistics), 340 p.

Kamino, S. (1962) : Nouka Rinka no Keiei (Management of Farm Household and ual Forest Owner). Chikyu Shuppan.

Kira, K. (1989) : Morozukamura no Ringyo Keiei (Forestry of Morozuka Village). Ringyo Keizai (Forest Economy), Forest Economic Research Institute, 42(12), p.

10.

Kitagawa, I. (1984) : Sozai Seisan no Keizai Kozo (Economic Structure of Log tion). Nihon Ringyo Chosakai, 246 p

Kooroki, K. (1996) : Ninaite-Rinka ni Kansuru Ichi Kousatu (Consideration about vidual Forest Owner), Ringyo Keizai (Forest Economy), Forest Economic Research

Institute, 49(7), p. 2-21.

Shiga, T. (1995) : Minyurin no Seisan kozo to Shinrin Kumiai (A Productive Structure of a Private Forest and Forest Owner's Association), Nihon Ringyo Chosakai, 416 p. Takano, T. and Arai, K. (2002) : Recent Regional Trends of the Forestry and Forestry

Cooperatives in Fukushima Prefecture, Fukushima Geographical Review, 45, p.

44.