IRUCAA@TDC : Association between feeding methods and sucking habits: a cross-sectional study of infants in their first 18 months of life

全文

(2) Bull Tokyo Dent Coll (2013) 54(4): 215–221. Original Article. Association between Feeding Methods and Sucking Habits: A Cross-sectional Study of Infants in Their First 18 Months of Life Takuro Yonezu, Taiko Arano-Kojima, Kaido Kumazawa and Seikou Shintani Department of Pediatric Dentistry, Tokyo Dental College, 1-2-2 Masago, Mihama-ku, Chiba 261-8502, Japan Received 15 January, 2013/Accepted for publication 30 April, 2013. Abstract The aim of this study is to investigate infant feeding patterns and to analyze the influence of breast-feeding methods on the prevalence of non-nutritive sucking habits in a sample of Japanese infants. A random sample of 353 mothers of infants of 18 months of age was interviewed at a public health facility in “K” city. The prevalence and duration of infant feeding patterns categorized as breast-feeding, partial breast-feeding, and bottlefeeding, were determined. The outcome investigated was the prevalence of non-nutritive sucking habits (pacifier use and finger sucking). The data were analyzed using the Chisquare and Fisher’s exact tests with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons to assess possible association between feeding method and non-nutritive sucking behavior. The infants were categorized into the following groups depending on feeding method: breast-feeding (27.2%), partial breast-feeding (32.0%), or bottle-feeding (40.8%). Among all infants, 13.9% used a pacifier, 18.4% sucked their fingers, and 0.3% had both habits at 18 months of age. Breast-feeding was negatively correlated with pacifier use and finger sucking. In contrast, bottle-feeding was strongly associated with pacifier use and finger sucking. These results suggest that breast-feeding provides benefits to infants, and that non-nutritive sucking habits may be avoided by promoting correct breast-feeding practices. Key words:. Breast-feeding — Bottle-feeding — Duration — Sucking habits — Infants. Introduction The sucking behaviors of infants are described in the literature13) as being of two types: nutritive and non-nutritive sucking. Thumb sucking, finger sucking, and sucking on a pacifier are considered as non-nutritive sucking. Great variations in non-nutritive sucking habits can be observed in different. cultures3). A large number of studies1,16–18,20–23) have indicated a higher incidence of malocclusion in children with persistent non-nutritive sucking habits than in those with no history of habits. Thus, there is strong evidence that thumb sucking and pacifier use are associated with dental malocclusion. Although, pacifier or other sucking devices. 215.

(3) 216. Yonezu T et al.. are given to infants to comfort and calm them4,12), it has been shown that the use of a pacifier in the early postpartum period, when the infant is learning to suck at the breast, may interfere with proper sucking and can contribute to so-called “nipple confusion”. Several studies2,7,15) have shown an association between shorter breast-feeding duration and pacifier use. These findings led the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF)19) to recommend against the use of pacifiers. This recommendation was incorporated as step 9 of the “Ten Step to Successful Breast-feeding”, which formed part of the WHO/UNICEF’s Baby-friendly Hospitals Initiative. However, Larsson9) has suggested that while the sucking instinct varies in degree among individual infants, it is usually powerful. Even after the infant is fed cereal or mother’s milk, the sucking urge often remains. The extent of this “surplus” sucking urge is dependent on the strength of the original urge, on how much that original urge has been satisfied, and on how much of it has been spent on the intake of nourishment. The surplus sucking urge may be either frustrated or re-channeled. For the child, the most attractive method (and probably the most original) means of satisfying this “surplus” urge is unrestricted nonnutritive sucking, where the child engages in either digit or pacifier sucking to obtain satisfaction. Therefore, it is hypothesized that the longer the children are breast-fed, the less chance they have using the pacifier or of sucking their thumbs and, consequently, the lower probability of developing malocclusion in childhood. The aim of the present study was to investigate breast-feeding patterns and analyze their influence on the prevalence of nonnutritive sucking habits in Japanese infants.. Materials and Methods 1. Participants This cross-sectional study was conducted at a public health care facility in a suburb of. “K” city in Tokyo, Japan. A sample of parents of infants aged 18 months was selected and interviewed. All the infants were Japanese, in good general health, had age-appropriate cognitive development, and had no history of orthodontic intervention. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tokyo Dental College (approval no. 277). The parents were asked to provide consent to the study and fill out a questionnaires on completion of a dental examination. These questionnaires included items on feeding methods and duration. Specifically, the instrument consisted of a pre-tested form with items related to the history of breast-feeding and bottle-feeding, and history of sucking habits. For this study, breast-feeding duration referred to the total duration of any breast-feeding, while bottle-feeding referred to feeding of the infant with liquid from a bottle with a nipple. An infant was considered to be breast-fed when he or she had received only breast milk with no other milk formula. An infant was considered to partial breast-fed when he or she had received breast milk as the main source of nourishment, but also received milk formula by bottle. An infant was considered to be bottle-fed when he or she had received only milk formula by bottle. Infants were considered pacifier users/finger suckers if they sucked a pacifier and/or their fingers for at least on episode every day.. Data Analysis The hypothesis tested was that breast-feeding practices are associated with the occurrence of sucking habits. The exposure factors were the breast-feeding categories and the outcome was the presence or absence of sucking habits. The association between breast- or bottle-feeding prevalence and each infant’s sucking habits (presence or absence of pacifier use and finger sucking) was assessed using the Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons; a p value of less than 0.017 was con sidered statistically significant. This signifi-.

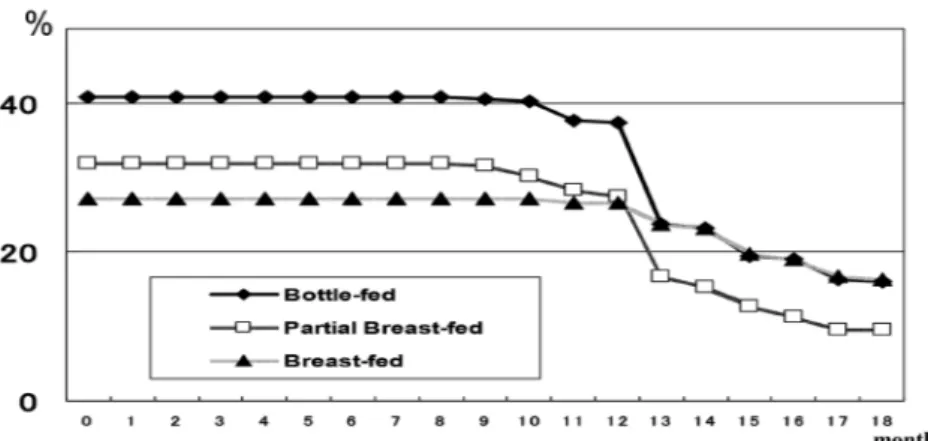

(4) Infant’s Feeding Methods and Sucking Habits. 217. Fig. 1 Comparison of duration of three forms of feeding method in Japanese infants during first 18 months of life. cance level corresponds to a 5% Bonferroni correction level.. Results All the expectant mothers who were invited to participate in this study agreed to do so. A total of 353 mothers were included and interviewed. 1. Feeding pattern Each infant was assigned to one of the following groups depending on feeding practices: exclusive breast-feeding (27.2%), partial breast-feeding (32.0%), or bottlefeeding (40.8%). We compared the duration in each category through 18 months of age, and the results are presented in Fig. 1. All exclusively breast-fed infants continued breast-feeding until 10 months of age, with 98% thereafter continuing to be breast-fed from between 10 to 12 months. Almost all bottle-fed infants con tinued bottle-feeding until 12 months of age, at which time weaning occurred until 13 months, when this proportion decreased steeply. A large proportion of partially breastfed infants was also weaned at 12 to 13 months of age, followed by a gradual decrease until 18 months of age.. Fig. 2 Prevalence of non-nutritive sucking habits in infants according to feeding method. 2. Sucking habits Thirty-three percent of all mothers reported that their child had at least one type of sucking habit at 18 months of age. Among all infants, 13.9% used a pacifier, 18.4% sucked their fingers, and 0.3% had both habits. 3. Feeding methods and sucking habits The results in Fig. 2 show that 2 (2.1%) of the breast-fed infants had a pacifier habit, compared to 30 (20.8%) of the bottle-fed infants and 18 (15.9 %) of the partial breastfed infants at 18 months of age. Tables 1, 2, and 3 show a comparison of the occurrence of sucking habits by duration of each type of feeding practice: exclusively breast-fed, bottlefed, and partial breast-fed infants, respectively..

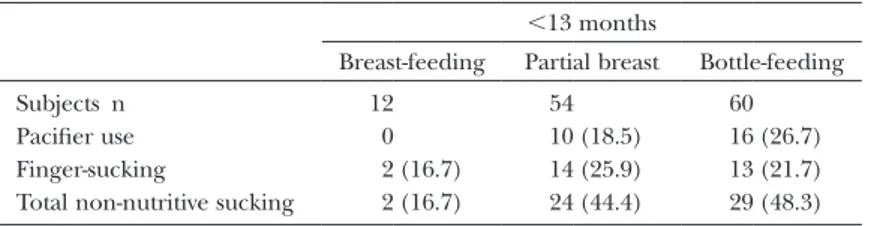

(5) 218. Yonezu T et al.. Table 1 Prevalence of non-nutritive sucking habits in breast-feeding infants by duration Breast-feeding duration Subjects n Pacifier use Finger-sucking Total non-nutritive sucking. <13 months. 13–15 months. 16–18 months. 12 0 2 (16.7) 2 (16.7). 17 1 (5.9) 0 1 (5.9). 67 1 (1.5) 5 (7.5) 6 (9.0) n (%). Table 2 Prevalence of non-nutritive sucking habits in bottle-feeding infants by duration Bottle-feeding duration Subjects n Pacifier use Finger-sucking Total non-nutritive sucking. <13 months. 13–15 months. 16–18 months. 60 16 (26.7) 13 (21.7) 29 (48.3). 17 7 (41.2) 6 (35.3) 13 (76.5). 67 7 (10.4) 17 (25.4) 24 (35.8). n (%) After Bonferroni correction, values of <0.017 were considered significant * Significant differences between 13–15months and 16–18 months group (p=0.003). Table 3 Prevalence of non-nutritive sucking habits in partial breast-feeding infants by duration Partial breast-feeding duration Subjects n Pacifier use Finger-sucking Total non-nutritive sucking. <13 months. 13–15 months. 16–18 months. 54 10 (18.5) 14 (25.9) 24 (44.4). 19 2 (10.5) 2 (10.5) 4 (21.1). 40 6 (15.0) 7 (17.5) 13 (32.5) n (%). In general, the prevalence of a pacifier habits was significantly lower in breast-fed infants than in bottle-fed or partial breast-fed infants. In other words, breast-feeding appeared to prevent the occurrence of sucking habits. 4. Feeding duration and sucking habits Tables 4, 5, and 6 show the occurrence of sucking habits in relation to the duration of each type of feeding practice. The occurrence of sucking habits in breast-fed infants decreased significantly with increase in duration of breast-feeding. The risk of sucking. habits in general was significantly lower in infants with prolonged breast-feeding than in those with shorter breast-feeding duration. The occurrence of a pacifier habit in infants bottle-feeding for more than 16 months was 10.4% compared with 41.2% in those who stopped bottle-feeding at between 13 and 15 months and 26.7% in those who bottle-fed less than 13 months. No significant association was observed between the duration and occurrence of sucking habits in partial breastfeeding infants..

(6) 219. Infant’s Feeding Methods and Sucking Habits. Table 4 Prevalence of non-nutritive sucking habits in infants according to type of feeding practice with short duration <13 months Subjects n Pacifier use Finger-sucking Total non-nutritive sucking. Breast-feeding. Partial breast. Bottle-feeding. 12 0 2 (16.7) 2 (16.7). 54 10 (18.5) 14 (25.9) 24 (44.4). 60 16 (26.7) 13 (21.7) 29 (48.3) n (%). Table 5 Prevalence of non-nutritive sucking habits in infants according to type of feeding practice with medium duration 13–15 months Subjects n Pacifier use Finger-sucking Total non-nutritive sucking. Breast-feeding. Partial breast. Bottle-feeding. 17 1 (5.9) 0 1 (5.9). 19 2 (10.5) 2 (10.5) 4 (21.1). 17 7 (41.2) 6 (35.3) 13 (76.5). n (%) After Bonferroni correction, values of <0.017 were considered significant. * Significant differences between breast-feeding and bottle-feeding group (p=0.000) and between partial breast-feeding and bottle-feeding group (p=0.002). Table 6 Prevalence of non-nutritive sucking habits in infants according to type of feeding practice with prolonged duration 16–18 months Subjects n Pacifier use Finger-sucking Total non-nutritive sucking. Breast-feeding. Partial breast. Bottle-feeding. 67 1 (1.5) 5 (7.5) 6 (9.0). 40 6 (15.0) 7 (17.5) 13 (32.5). 67 7 (10.4) 17 (25.4) 24 (35.8). n (%) After Bonferroni correction, values of <0.017 were considered significant. * Significant differences between breast-feeding and bottle-feeding group (p=0.000) and between breast-feeding and partial breast-feeding group (p=0.002). Discussion Current preventive procedures emphasize early recognition and treatment of malocclusion. Specific and timely information regarding disharmonies in the primary dentition is, therefore, very important. Therefore, knowledge about the etiology of malocclusion is essential for the success of preventive and. interceptive orthodontics treatment as such treatment usually requires the elimination of these causes. Non-nutritive sucking is a common behavior among young children in various populations3), and the relationship between prolonged non-nutritional sucking habits and occlusal abnormalities has been studied extensively1,16–18,20–23). For example, Warren and.

(7) 220. Yonezu T et al.. Yonezu et al.17,18) reported that prolonged nonnutritive sucking habits were associated with changes in several dental arch measurements, such as decreased maxillary arch width, increased overjet, and decreased overbite. In addition, Yonezu et al.20) reported that those with prolonged non-nutritional sucking habits were more likely to have anterior openbite and posterior crossbite. In addition, the association between pacifier use and the shorter maternal breast feeding duration is already well-established. According to Victora et al.14), the use of a pacifier reduces the number of times the child suckles per day and, consequently, there is less stimulation of the breast and less milk production, culminating in weaning. Another author10) believes that, children who use a pacifier have more difficulty in obtaining milk from the breast due to “suction confusion” caused by differences in the suction technique between the pacifier and the breast, also culminating in weaning. Another consideration is the association between the method of infant feeding and the development of non-nutritive sucking habits. Many previous studies5,6,13) have reported that the prevalence of non-nutritive sucking habits was significantly higher among bottlefed children. In the present study, the number of children with non-nutritive sucking habits was observed to decrease with increase in duration of bottle-feeding duration (Table 2). However, the main finding of this study revealed that, breast-feeding protected against the occurrence of non-nutritive sucking habits during early childhood. A significantly fewer percentage of children who were breastfed had non-nutritive sucking habits in comparison with in those who were bottle-fed or partial breast-fed children (Tables 5, 6). In addition, there are theoretical mechanisms by which bottle-feeding might contribute to the development of malocclusion, including (1) a direct effect to altered sucking mechanics on the growing facial bones of the infant: and (2) an increased tendency toward abnormal swallowing patterns as a result of bottle feeding. Yonezu et al.22) reported that,. excessive overbite tended to be more prevalent with increased bottle-feeding duration, although the association was not statistically significant. In their study, children with nonnutritive sucking habits (finger or pacifier) were excluded from the analyses, which evaluated the association between methods of infant feeding and occlusion. This suggests that bottle-feeding influences the development of a deep-bite and increases the likelihood that the child will develop nonnutritive sucking habits, thus increasing the chance of development of open-bite or excessive overjet. Breast-feeding provides multiple nutritional, immunological, and psychological benefits to the infant in its early period of life. Systematic reviews8,11) have shown strong evidence in favor of this practice. The WHO recommends that infants be exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months of life, with some breast-feeding continuing for up to 2 years. In addition, starting from the premise that bottles and pacifiers can be obstacles to successful breast-feeding, the WHO, in conjunction with UNICEF19), recommends not using bottles or pacifiers in maternity units with breast-fed children in their “Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding”. It seems that the act of breast-feeding has positive effects on the development of an infant’s oral cavity improving shaping of the hard palate, resulting in proper alignment of the teeth and fewer problems with malocclusion. If act of breast-feeding can prevent the development of sucking habits in children in their first 18 months of life, that is yet one more reason to promote breast-feeding practices. The findings of this study must be considered preliminary because of the relatively small sample size. A further study with a larger sample size and more varied feeding duration is warranted.. Acknowledgements We would like to thank Professor Warren of the College of Dentistry at The University.

(8) Infant’s Feeding Methods and Sucking Habits. of Iowa for his assistance with the English of this manuscript.. References 1) Adair SM, Milano M, Lorenzo I, Russell C (1995) Effects of current and former pacifier use on the dentition of 24- to 59-month-old children. Pediatr Dent 17:437–444. 2) Barros FC, Victora CG, Semer TC, Tonioli Filho S, Tomasi E, Weiderpass E (1995) Use of pacifier is associated with decrease breastfeeding duration. Pediatrics 95:497–499. 3) Caglar E, Larsson E, Andersson EM, Hauge MS, Ogaard B, Bishara S, Warren J, Noda T, Dolci GS (2005) Feeding, artificial sucking habits, and malocclusions in 3-year-old girls in different regions of the world. J Dent Child 72:25–30. 4) Carbajal R, Chauvet X, Couderc S, OlivirMartin M (1999) Randomised trial of analgesic effects of sucrose, glucose, and pacifiers in term neonates. BMJ 319:1393–1397. 5) Charchut SW, Allred EN, Needleman HL (2003) The effects of infant feeding patterns on the occlusion of the primary dentition. J Dent Child 70:197–203. 6) Farsi NM, Salama FS (1997) Sucking habits in Saudi children: Prevalence, contribution factors, and effects on the primary dentition. Pediatr Dent 19:28–33. 7) Howard CR, Howard FM, Lanphear B, deBlieck EA, Eberly S, Lawrence RA (1999) The effects of early pacifier use on breastfeeding duration. Pediatrics 103:E33. 8) Kramer MS, Kakuma R (2012) Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, Aug 15;8:CD003517. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003517.pub2. 9) Larsson E (2001) Sucking, chewing, and feeding habits and the development of crossbite: A longitudinal study of girls from birth to 3 years of age. Angle Orthod 71:116–119. 10) Neifert M, Lawrence R, Seacat J (1995) Nipple confusion: toward a formal definition. J Pediatr 126 Suppl 6:125–129. 11) Owen CG, Martin RM, Whincup PH, Smith GD, Cook DG (2005) Effect of infant feeding on the risk of obesity across the life course: A quantitative review of published evidence. Pediatrics 115:1367–1377. 12) Pinelli J, Symington A (2000) How rewarding can a pacifier be? A systematic review of nonnutritive sucking in preterm infants. Neonatal. 221. Netw 19:41–48. 13) Turgeon-O’Brien H, Lachapelle D, Gagnon PF, Larocque I, Meheu-Robert L (1996) Nutritive and nonnutritive sucking habits: A review. J Dent Child 63:321–327. 14) Victora CG, Behague DP, Barros FC, Olinto MT, Weiderpass E (1997) Pacifier use and short breastfeeding duration: cause, consequence, or coincidence? Pediatrics 99:445–453. 15) Victora CG, Tomasi E, Olinto MT, Barros FC (1993) Use of pacifiers and breastfeeding duration. Lancet 341:404–406. 16) Warren JJ, Bishara SE (2002) Duration of nutritive and non-nutritive sucking behaviors and their effects on the dental arches in the primary dentition. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 121:347–356. 17) Warren JJ, Bishara SE, Steinboch KL, Yonezu T, Nowak AJ (2001) Effects of oral habits’ duration on dental characteristics in the primary dentition. J Am Dent Assoc 132:1685– 1693. 18) Warren JJ, Slayton RL, Bishara SE, Levy SM, Yonezu T, Kanellis MJ (2005) Effects of nonnutritive sucking habits on occlusal characteristics in the mixed dentition. Pediatr Dent 27: 445–450. 19) World Health Organization/UNICEF (1991) Innocenti Declaration on the protection, promotion and support of breastfeeding. Ecol Food Nutr 26:271–273. 20) Yonezu T, Kurosu M, Ushida N, Yakushiji M (2005) Effects of prolonged non-nutritive sucking on occlusal characteristics in the primary dentition. Dentistry in Japan 41:107–112. 21) Yonezu T, Machida Y (1998) Finger sucking: A longitudinal study of its prevalence, duration and malocclusion consequences. Jpn J Pediatr Dent 36:93–100. (in Japanese) 22) Yonezu T, Ushida N, Yakushiji M (2005) Effects of prolonged breast- and bottle-feeding on occlusal characteristics in the primary dentition. Pediatric Dental Journal 15:176–179. 23) Zardetto CG, Rodrigues CR, Stefani FM (2002) Effects of different pacifiers on the primary dentition and oral myofunctional structures of preschool children. Pediatr Dent 24:552–560. Reprint requests to: Dr. Takuro Yonezu Department of Pediatric Dentistry, Tokyo Dental College, 1-2-2 Masago, Mihama-ku, Chiba 261-8502, Japan E-mail: tayonezu@tdc.ac.jp.

(9)

図

関連したドキュメント

In this, the first ever in-depth study of the econometric practice of nonaca- demic economists, I analyse the way economists in business and government currently approach

The aim of this paper is to investigate relations among various elliptic Harnack inequalities and to study their stability for symmetric non-local Dirichlet forms under a

He thereby extended his method to the investigation of boundary value problems of couple-stress elasticity, thermoelasticity and other generalized models of an elastic

Keywords: continuous time random walk, Brownian motion, collision time, skew Young tableaux, tandem queue.. AMS 2000 Subject Classification: Primary:

Then it follows immediately from a suitable version of “Hensel’s Lemma” [cf., e.g., the argument of [4], Lemma 2.1] that S may be obtained, as the notation suggests, as the m A

Section 3 is first devoted to the study of a-priori bounds for positive solutions to problem (D) and then to prove our main theorem by using Leray Schauder degree arguments.. To show

This paper presents an investigation into the mechanics of this specific problem and develops an analytical approach that accounts for the effects of geometrical and material data on

Beyond proving existence, we can show that the solution given in Theorem 2.2 is of Laplace transform type, modulo an appropriate error, as shown in the next theorem..