九州大学学術情報リポジトリ

Kyushu University Institutional Repository

日本語とポーランド語におけるアイデンティティの 言語的構築に見られるジェンダー差および文化差

バルトシュ, ヴォランスキ

https://doi.org/10.15017/1866240

出版情報:Kyushu University, 2017, 博士(比較社会文化), 課程博士 バージョン:

権利関係:

Gender and cultural differences in linguistic constructions of identity

in Japanese and Polish

(日本語とポーランド語におけるアイデンティティの 言語的構築に見られるジェンダー差および文化差)

Bartosz Wolański

Table of Contents

Chapter 1 Introduction ... 1

1.1. Research background ... 1

1.2. Research questions ... 1

1.3. Structure of the dissertation ... 3

Chapter 2 Literature Review ... 6

2.1. Definitions ... 6

2.1.1. Identity ... 6

2.1.2. Gender ... 6

2.1.3. Culture ... 7

2.2. Literature review ... 7

2.2.1. Identity ... 7

2.2.2. Gender ... 12

2.2.3. Culture ... 15

Chapter 3 Creating and maintaining identity: personal reference to others . 17 3.1. Personal reference in blogs ... 18

3.1.1. Communicating on a blog ... 19

3.1.2. Self-presentation in “official blogs” ... 20

3.1.3. Personal reference as a response to self-presentation ... 22

3.1.4. Japanese ... 23

3.1.4.1. Blogs in Japan ... 23

3.1.4.2. Data and methodology of this study ... 24

3.1.4.3. Results: cute Momo and quirky Kintaro ... 27

3.1.4.4. Results: boyish Kenji and Kensuke the father ... 31

3.1.4.5. Closing remarks ... 33

3.1.5. Polish ... 35

3.1.5.1. Data and methodology of this study ... 36

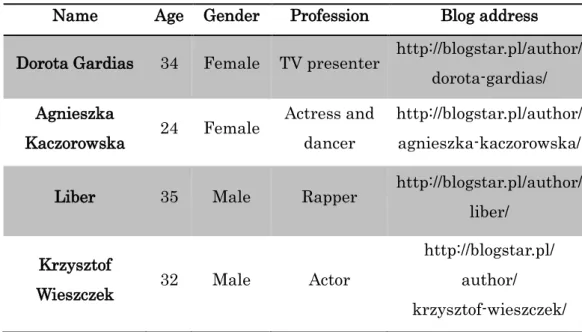

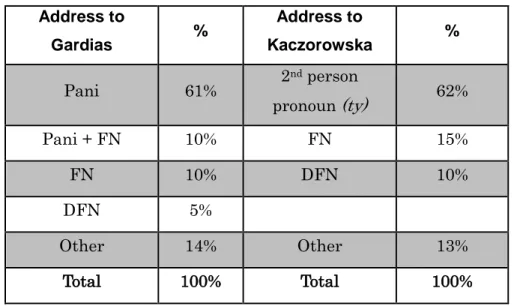

3.1.5.2. Results: mature Mrs. Gardias, Agnieszka the girl-next-door .... 39

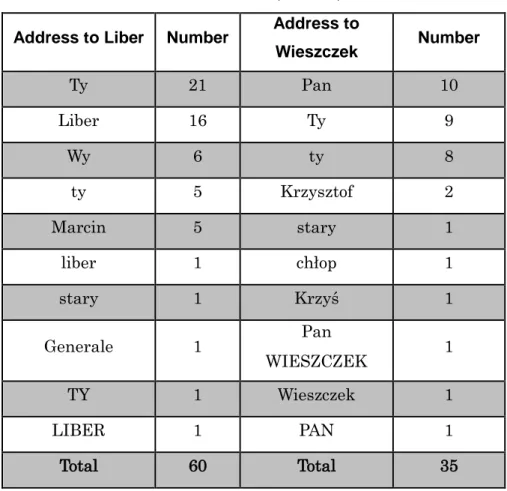

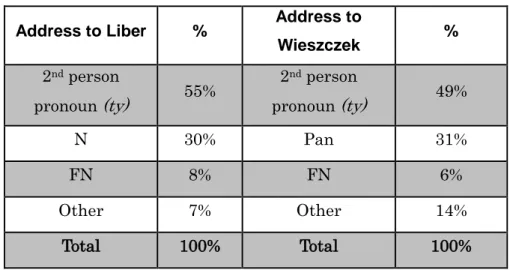

3.1.5.3. Results: Liber the ex-rapper,

Wieszczek the athletic actor ... 44

3.2. Personal reference in natural conversation ... 48

3.2.1. Japanese ... 50

3.2.2. Polish ... 56

3.3. Attitudes towards address terms ... 60

3.3.1. Profile of survey informants ... 61

3.3.2. Japanese results ... 62

3.3.3. Polish results ... 75

3.4. Summary ... 92

Chapter 4 Attacking the identity: taboo language and verbal aggression ... 93

4.1. Taboo language in corpora of written text ... 98

4.1.1. Japanese ... 99

4.1.1.1. Characteristics of the Japanese corpus... 99

4.1.1.2. Taboo words selected for this study ... 99

4.1.1.3. Results ... 103

4.1.2. Polish ... 108

4.1.2.1. Taboo language and normative linguistics in Poland .... 108

4.1.2.2. Characteristics of the Polish corpus ... 111

4.1.2.3. Taboo words selected for this study ... 113

4.1.2.4. Results ... 123

4.2. Verbal aggression on the internet ... 126

4.2.1. Japanese ... 134

4.2.2. Polish ... 144

4.3. Taboo language and verbal aggression in natural conversation ... 150

4.3.1. Japanese ... 150

4.3.2. Polish ... 153

4.4. Attitudes towards taboo language and verbal aggression ... 162

4.4.1. The object of this study ... 162

4.4.2. Results ... 164

4.5. Summary ... 179

Chapter 5 Borrowing identities: quotations in speech. ... 180

5.1. Quotations as constructions ... 180

5.2. Quotations in natural conversations ... 182

5.2.1. Japanese ... 182

5.2.2. Polish ... 186

5.3. Cross-gender quoting ... 188

5.4. Summary ... 190

Chapter 6 Gender and Identity in Japanese and Polish ... 191

6.1. Gender ... 191

6.1.1. Negotiating masculinity and femininity ... 191

6.1.2. Sexual taboo in everyday communication ... 194

6.2. Address terms: pronouns and names ... 196

6.3. The perception of aggression ... 197

6.4. Notes about religious and national identity ... 198

Chapter 7 Conclusions ... 201

7.1. Summary ... 201

7.2. Significance of this study ... 202

7.3. Limitations and suggestions for further research ... 203

References ... 205

Original titles of Japanese language references ... 212

List of Tables

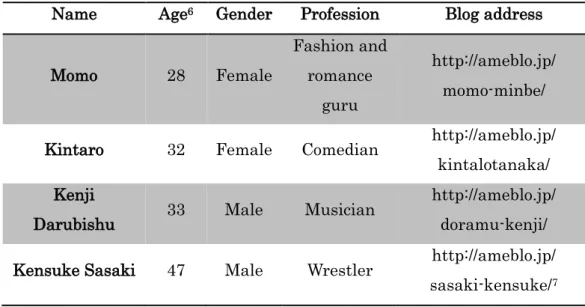

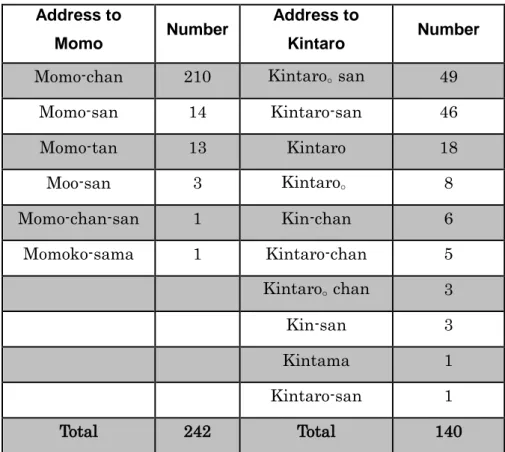

Table 1: Japanese bloggers ... 25Table 2: References to Momo and Kintaro (detailed) ... 28

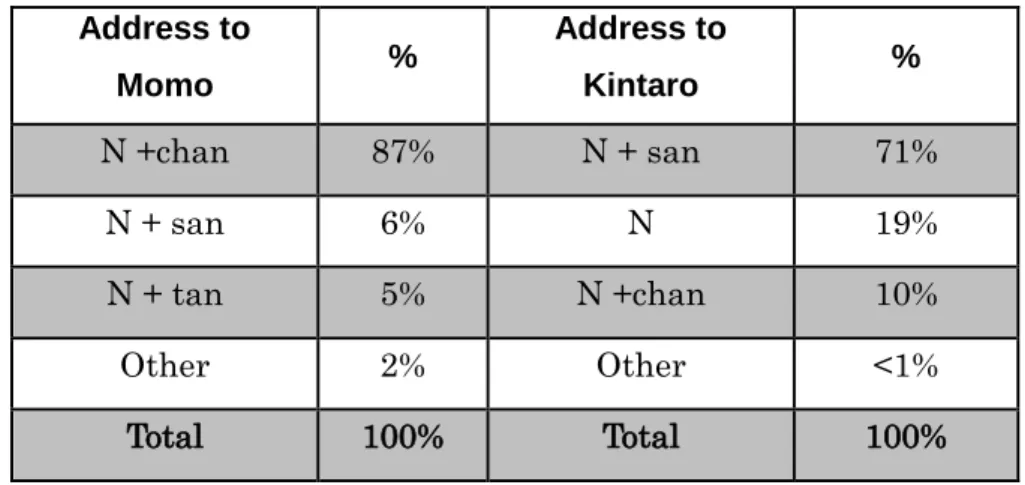

Table 3: References to Momo and Kintaro (categorized) ... 29

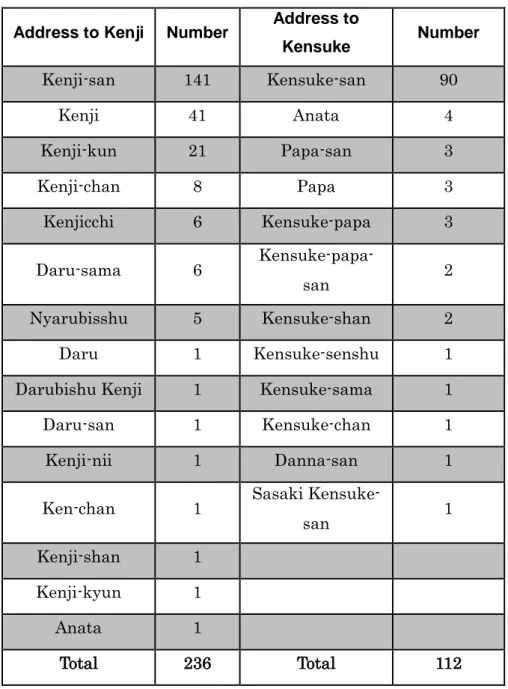

Table 4: References to Kenji and Kensuke (detailed) ... 31

Table 5: References to Kenji and Kensuke (categorized) ... 32

Table 6: Polish bloggers ... 37

Table 7: References to Gardias and Kaczorowska (detailed)... 39

Table 8: References to Gardias and Kaczorowska (categorized) ... 41

Table 9: References to Liber and Wieszczek (detailed) ... 44

Table 10: References to Liber and Wieszczek (categorized) ... 45

Table 11: Information about conversation excerpts ... 49

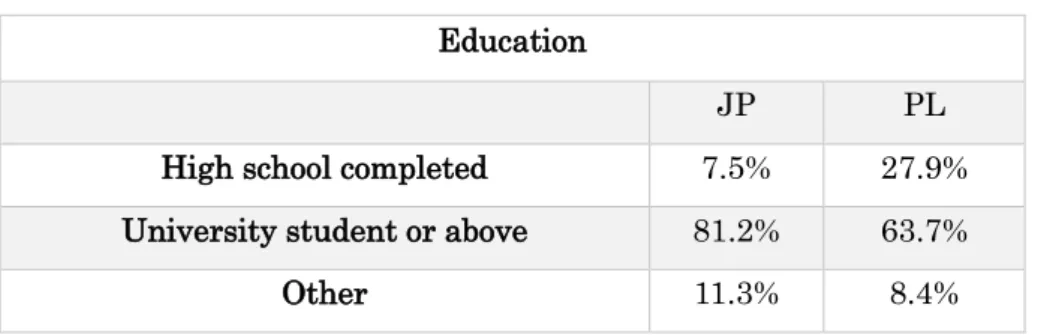

Table 12: Survey respondents’ education ... 61

Table 13: Japanese address from own children ... 63

Table 14: Japanese address to own children ... 64

Table 15: Japanese address from others' children ... 65

Table 16: Japanese address to others' children ... 66

Table 17: Japanese address from partner ... 66

Table 18: Japanese address to partner ... 67

Table 19: Japanese address from adult family ... 68

Table 20: Japanese address to adult family... 69

Table 21: Japanese address from close friends ... 69

Table 22: Japanese address to close friends ... 70

Table 23: Japanese address from acquaintances ... 70

Table 24: Japanese address to acquaintances ... 71

Table 25: Japanese address from strangers ... 72

Table 26: Japanese address to strangers ... 72

Table 27: Japanese address from higher ranked persons ... 74

Table 28: Japanese address to higher ranked persons ... 75

Table 29: Polish address from own children ... 77

Table 30: Polish address to own children... 81

Table 31: Polish address from others' children ... 81

Table 32: Polish address to others' children ... 82

Table 33: Polish address from partner ... 83

Table 34: Polish address to partner ... 83

Table 35: Polish address from adult family ... 84

Table 36: Polish address to adult family ... 84

Table 37: Polish address from close friends ... 86

Table 38: Polish address to close friends ... 86

Table 39: Polish address from acquaintances ... 87

Table 40: Polish address to acquaintances ... 87

Table 41: Polish address from strangers ... 88

Table 42: Polish address to strangers ... 89

Table 43: Polish address from higher ranking persons ... 89

Table 44: Polish address to higher ranking persons ... 90

Table 45: Humorous insulting address ... 90

Table 46: Pronominal forms in the Japanese corpus ... 103

Table 47: Co-occurrences of ore/boku with sentence-final particles ... 104

Table 48: Co-occurrences of atashi/atakushi with sentence-final particles .. 105

Table 49: Co-occurrences of ore/boku with taboo ... 107

Table 50: Co-occurrences of atashi/atakushi with taboo ... 107

Table 51: Polish usage of taboo ... 111

Table 52: Polish self-censoring in the presence of children ... 111

Table 53: Japanese verbal aggression online ... 134

Table 54: Categorization of insults ... 135

Table 55: Targets of Japanese verbal aggression ... 136

Table 56: Polish verbal aggression online ... 144

Table 57: Targets of Polish verbal aggresion ... 147

Table 58: Frequency of swearing... 165

Table 59: Reasons for swearing ... 166

Table 60: Swearing and listener ... 168

Table 61: Self-censoring ... 170

Table 62: Reasons for self-censoring ... 172

Table 63: Thinking about swearing and feelings of discomfort ... 174

Table 64: Swearing on the internet - receiving ... 175

Table 65: Swearing on the internet - sending ... 175

Table 66: Taboo address as humor ... 176

Table 67: Frequency of internet use ... 177

Table 68: Euphemisms - frequency of use... 178

Table 69: Cross-gender quoting and emotional comfort - Polish ... 189

Table 70: Cross-gender quoting and emotional comfort - Japanese ... 189

List of Figures

Figure 1: Kurwa – speaker’s gender and meaning ... 115Figure 2: Kurwa – speaker's and addressee's gender ... 116

Figure 3: Chuj – speaker's gender ... 122

Figure 4: Chuj – meaning and speaker's gender ... 122

Figure 5: Chuj – speaker's and addressee's gender ... 123

Figure 6: Kurwa - speaker's gender ... 124

List of Recorded Conversation Excerpts

Excerpt 1... 50

Excerpt 2... 51

Excerpt 3... 56

Excerpt 4... 59

Excerpt 5... 150

Excerpt 6... 153

Excerpt 7... 155

Excerpt 8... 155

Excerpt 9... 156

Excerpt 10 ... 157

Excerpt 11 ... 158

Excerpt 12 ... 160

Excerpt 13 ... 160

Excerpt 14 ... 182

Excerpt 15 ... 185

Excerpt 16 ... 186

Excerpt 17 ... 187

Excerpt 18 ... 192

Excerpt 19 ... 193

1

Chapter 1 Introduction

1.1. Research background

The concept of identity has garnered special attention of language and society scholars in the last few decades. The connection between gender and identity has also been well studied (e.g. Butler 1990, Benwell and Stokoe 2006).

However, identity in Polish discourse tends to be understood in terms of mostly ethnic or national identity,1 rather than as an immensely multifaceted concept.

More importantly, no comparison describing in relative terms the patterns of identity construction in Japanese and Polish communities has been performed to date.

1.2. Research questions

The main question asked in this research is: What are the differences in the ways Japanese and Polish speakers of different genders construct identity, respond to it, or contest it within discourse? In order to narrow down this broad topic, this research focuses on address terms as means of creating and upholding an identity, and verbal aggression – including taboo language – as means of attacking or challenging it. The third and final phenomenon discussed in this paper is quotation: the act of bringing up the words of another person within your own, including cases in which the phrasing is inaccurate, or the person fictitious.

These are of course only a few of the many parts of language relevant to identity management, which is a topic that can be approached from a multitude of angles and using various methodologies. However, it can be said that the objects of this study are good representatives for some major aspects of the linguistic negotiation of identity. Address terms are succinct labels you

1 Part of the data analysed in this dissertation comes from a survey concerning the linguistic phenomena of address terms, taboo language and quotations. Some of the Polish respondents commented that they do not see the connection between those issues and the question of identity.

2

give another person, and they may construct an identity by condensing any number of traits that person possesses, both objective and subjective. In other words, address terms are names given to identities. Verbal aggression, on the other hand, can be understood as an assault on the identity of another. This can be achieved by denying the targets of the aggression their desired identity or by forcing upon them one which is undesirable (but it needs to be said that what seems to be an act of aggression out of context can turn out to be an expression of bonhomie after understanding the situation more deeply). This point is further discussed in chapter 4. Meanwhile, quotations can mean temporarily assuming the identity of another. In spoken language, speakers may do more than just replicate the words of another person when quoting.

They may also attempt to imitate other components accompanying the original utterance, such as the pitch, gestures or facial expressions. Although widely known as “reported speech,” this behavior can be more than just a dry report - sometimes it is a performance. As such, this dissertation examines some ways in which the linguistic construction, destruction and multiplication of identities can take place.

An area of special interest for the author was the question of gender differences in the use of the selected forms, as gender is one of the fundamental building blocks of identity. That is also true in the legal sense – in any document identifying an individual, gender is likely to feature as one of the first items on the list. Gender identity can be displayed overtly, with an explicit verbal reference. One example from within the scope of this study would be address terms based on kinship, frequently based on the gender of the addressee (e.g. “Mum”). However, gender may also influence identity management in less direct ways. In incidents of verbal aggression studied in the present work, few speakers made any explicit statements close to “I do this because I am a woman,” “I do this because I am a man,” but nonetheless the data suggest that gender does seem to affect this kind of act. This work does not ignore the fact that it is not enough to speak about “masculinity” and

“femininity” in the singular, because different varieties of gendered behavior can coexist within the same sex (or even the same person). Some examples of such gender expressions are discussed chapter 3.1, which studies different manners of self-presentation in celebrity blog posts.

3

This dissertation compares the linguistic behavior of Japanese and Polish people, focusing mostly on the common dialects of either language.

These two cultures have been chosen because they have never been compared side by side in research with a focus on linguistic identity.

The reader will encounter the term “speaker” throughout this dissertation, but it should be noted that it is not used in the narrow, literal sense, but rather refers to anyone broadcasting language in any form. While some chapters are indeed concerned with face-to-face conversations, others investigate text-based communication such as that used on the Internet. By using language, speakers can create their identities, maintain them or change them. A speaker can also use language to approve or challenge the identity of another person. What is considered a desirable image will vary from one person to another, but the values of a given culture will also reflect on the models that guide the linguistic behavior of its members.

1.3. Structure of the dissertation

The first chapter of this dissertation serves as an introduction of the research background, the research question and the content of the rest of the study.

Chapter 2 provides background on the definitions of the key concepts fundamental essential to the empirical analyses of later chapters: identity, culture and gender. It explains the concept of identity as used in this dissertation, namely as one or several characteristics of an individual which become salient in discourse. It also argues that identity understood in this way can be grounded in objectively verifiable reality instead of being a pure social construction. Next, the classic concept of “positive face” is linked to identity.

Finally, special gender expressions are introduced as an element of Japanese (sentence final particles and pronominal forms) and Polish (grammatical gender). These forms are further discussed in later chapters, with examples.

Chapters 3 to 5 are empirical studies of the phenomena that are the focus of this dissertation. I opted to use wide variety of data, including recorded and transcribed conversations, language from social networking sites and blogs, as well as large corpora of texts mostly extracted from works of fiction and organized by third parties. This variety provides differing outlooks on the aspects of language that are the main focus of this research. In private

4

conversation the audience is limited, but the self is exposed. One’s body is in plain sight, and voice is the medium of choice – and people are so attuned to picking up miniscule variations in voice that it allows the identification of individuals. Within Internet-based communication, the opposite is true.

Selected parts of identity can be effectively hidden and substituted with an online persona, but the size of the audience can potentially reach millions.

Those differences affect the ways in which identity is managed and using both kinds of data broadens the perspective on the topic. Using works of fiction as data, on the other hand, allows a glimpse into the gender stereotypes that are present within a community, the characters and their words being born in the minds of the authors who were shaped by their cultural milieu. Finally, in order to mitigate the ever-present risk of completely subjective interpretation when discussing the data, questionnaires were distributed among native speakers of both languages, with the aim of understanding their attitudes towards the relevant phenomena.

Chapter 3 focuses on terms of address as a way of constructing and upholding an identity. The first section analyses the texts that Japanese and Polish celebrities post on their blogs, and the comments written by readers of the blogs in response. Then, fragments of recorded conversations are used to demonstrate how the speakers can negotiate identity in interaction and which address terms they may use to identify others. This chapter also includes the results of the questionnaire concerning address terms. One of the significant differences found was the trend to prefer first names in Polish address and last names in Japanese, relatively speaking.

In Chapter 4, verbal aggression and taboo language are discussed as a potential hostile rejection of an identity, or as a way to ascribe an undesirable identity to another person. The study of corpora suggests that both in Japanese and Polish fiction, vulgar and offensive language is linked to masculinity more than femininity. The study of non-anonymous Internet communication on social media confirms that the same trend is also present in this area of natural language, and that furthermore verbal aggression and taboo language is more prevalent in Polish online discourse than Japanese. Using examples from recorded conversations, I also demonstrate how in some contexts the language studied in this chapter can be used not to offend, but to promote solidarity. The

5

questionnaire results relevant to this section show national differences similar to those found in the study of internet communication.

Chapter 5 talks about the act of quoting another person’s utterance, interpreted in this study as a replication of that person’s identity, or more likely as an original creation of a new identity loosely based on reality. Based on excerpts from conversations, some Japanese sentence final particles are shown to be used as a way to create colorful characters in conversation to engage other participants. A difference is also revealed in the attitudes of Japanese and Polish speakers toward quoting an utterance marked with a gender which does not match their own.

Chapter 6 attempts to draw conclusions about the desirable images of masculinity and femininity in Poland and Japan. This chapter describes the appeal of masculine language as perceived by some speakers, and the differences in this perception between the two cultures. This chapter also includes insights regarding the use of family names and given names as identity labels in Poland and Japan, as well as some minor observations concerning religious and national identity as expressed in the collected data.

6

Chapter 2 Literature Review

2.1. Definitions

The following sections will provide the definitions for the key concepts central to this dissertation: identity, gender and culture.

2.1.1. Identity

For the purpose of this study, “identity” can be defined as a personal characteristic (or a set of characteristics) that is invoked within discourse and consequently becomes salient in its context. That characteristic may be based on verifiable reality or a pure social construct. The view of identity presented in this dissertation is close to that of Deckert and Vickers (2011 : 9) who make a distinction between their understanding of identity and the legal interpretation, by saying that identity is “not something that can be stolen.”

They also contrast their view of identity with a mere sense of self, as identity may be ascribed by another person, sometimes in contradiction to one’s own self-perception. That is an issue that will be discussed with examples in the data chapters of this dissertation.

2.1.2. Gender

The meaning of gender as adopted by this dissertation is what is described by Buchanan (2010 : 198) as:

“The set of behavioural, cultural, psychological, and social characteristics and practices associated with masculinity and femininity.”

This puts gender in opposition to biological sex as an innate and less malleable trait. Although biological sex will be relevant to some of the findings, this dissertation will predominantly be concerned with Polish and Japanese ideas about femininity and masculinity.

7

2.1.3. Culture

Although culture is notorious for having a multitude of proposed definitions, I adopt Neuliep’s (2017) culture as “an accumulated pattern of values, beliefs and behaviors shared by an identifiable group of people with a common history and verbal and nonverbal symbol systems,” since it is appropriate for the Japanese and Polish as groups of native language users.

2.2. Literature review

2.2.1. Identity

Identity stems from the vast array of personal attributes and affiliations that collectively form an image of the individual. Identity can be built on the foundation of a plethora of possible salient traits, which include age, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, religion, political views, profession, social position and family status. These are some of the most important aspects of identity, but the list can go on forever, because anything can become relevant to identity when people make it so. This can include attributing high importance to such seemingly trivial features like hair color (“All redheads are crazy,” as the title of a certain rock song explains) or the preferred game console system (“I’m a PlayStation fanboy, and I’m proud of it”).

Identity can be viewed from at least two major standpoints: one is called the “essentialist” perspective and the other “constructionist” (see Benwell and Stokoe 2006 : 50). An essentialist view of identity says that identity is a stable and inherent characteristic of a person and there is such a thing as “true” identity. On the other hand, constructionists claim that no true essence of identity can ever be found, and it does not exist prior to discourse, but is instead created within it.

Bauman (2000 : 1), in a constructionist vein, presents a view of identity which attributes agency to those who adopt it, describing it more as a conscious choice of an actor rather than a passive acceptance of a predefined background:

“In this perspective, identity is an emergent construction, the situated outcome of a rhetorical and interpretive process in which interactants make situationally motivated selections from socially constituted repertoires of

8

identificational and affiliational resources and craft these semiotic resources into identity claims for presentation to others.”

Bauman (2000 : 1)

Tracy and Robles (2013 : 21-23) propose three main kinds of identity meaningful to “everyday talk,” which is a genre strongly represented in the present study. Each of those three types has varying levels of stability. The first kind – master identity – consists of those traits which are considered to be fairly static and difficult to change, such as nationality, gender or age.

Interactional identity, on the other hand, is dependent on the role or position that a person is taking at a given moment in a given context, and is more dynamic. Examples include the identity of a friend, a spouse, or a professional performing certain job. Such roles are contingent on the character of the relationship with the particular person with whom the speaker is communicating. Finally, relational identities refer to personality traits such as

“tolerant or bigoted,” “serious or fun-loving,” “friendly or aloof,” etc. Relational identities also describe the qualities of interpersonal relations such as “warm or hostile,” or “equal or superior.”

Tracy and Robles’ approach finds a reasonable middle ground between essentialism and constructionism, and such middle ground is also the position taken in this dissertation. While identity definitely can be and is in fact conjured within talk as an ephemeral construct, it can still be anchored in intrinsic, objective and relatively stable qualities of an individual. However, what kind of meaning is ascribed to a given part of reality can sometimes be a completely arbitrary choice of language users.

For example, in the modern world, race as an aspect of identity has inarguably great importance, but if one strips away the cultural associations, what we call race is in essence little more than an evolutionary adaptation to the climate which one’s ancestors had to endure. If your habitat receives large amounts of sunlight, it is good to have dark skin to protect the body from damaging radiation. Conversely, if the place where one lives receives little sunlight, such protection is less important. Indeed, decreased blockage of ultraviolet rays becomes important to good health because a moderate amount of sunlight is beneficial (Jablonski 2010). This difference, which appeared for

9

such prosaic reasons, has been elevated to the status of one of the core aspects of identity, deepening national and religious divides with which it might intersect, while also becoming a divide in itself. A physiological feature which might not in itself have much relevance to social life grows in the eye of the beholder to monumental proportions and ultimately gives birth to prejudices which do profoundly impact the lives of individuals. Lieberman and Reynolds (1996) show how such “prodigious baggage of misconceptions and heritage of horror” has caused scientists in the United States to gradually abandon the concept of biological race altogether.

Perhaps because racial minorities are much smaller in Poland than in the U.S., Kaszycka and Štrkalj (2002) suggest that in Polish society, race is a less sensitive topic. Still, the results of their survey show a large generational difference in the attitudes towards race among Polish anthropologists, with most scholars in the field older than 53 agreeing with the statement that there are biological races (subspecies) within

homo sapiens

, and most scholars below that age rejecting it. This gap may be a sign that race as a concept that categorically divides people may be in decline in Poland as well.Hence, even if identity is built upon a factual referent that exists prior to its linguistic expression and is independent of it, the meaning that is attached to that referent is constructed and volatile. The basic conditions necessary for a person to be identified as a “redhead” are subject to visual verification (with some possible grey areas, as it were), but what connotations does this identity carry? What is its historical baggage? Why is it even invoked in a given context, what makes it relevant to the then-and-there? The process of the construction of meaning is an interaction between the speaker, other participants of discourse, and the context.

The term “identity” will be used here in the abovementioned sociolinguistic sense. Although chapters concerned with computer mediated communication (CMC) will touch upon the subject of anonymity – which allows to hide the identity in the legal sense of personal information such as the name or age – the notion of identity that is the central theme of this dissertation refers to something less concrete, not always verifiable, and considerably broader in meaning.

In earlier research, I discussed how terms of address place users of

10

language in subjective and objective hierarchies. In this context, objective status refers to a position which can be subjected to a “true/false” verification, and subjective status to something which cannot be verified in this manner.

For example, military ranks such as “sergeant” are available as titles with which soldiers holding the appropriate rank can (and sometimes must) be addressed. Holding the rank is a fact that is legally noted and claiming to be a sergeant without possessing the necessary qualifications can constitute a criminal offense. On the other hand, being called by the Japanese pseudo- pronoun

kimi

does not signify that one holds a position in any verifiable hierarchy, only that the recipient of the form is unlikely to have a higher social status than the speaker, in a general sense.Kimi

is not a formal title bestowed by an authority, nor is it judicially relevant.However, this subjective/objective binary is based only on the feasibility of verification, regardless of whether the object of the verification is a tangible part of reality or a pure social construct. The fact of being a sergeant is clearly an example of the latter: conferring the rank does not in itself bring about any direct change in the physical reality, but at most brings about changes in the social realm by granting certain powers, privileges and responsibilities, which only have any weight if other members of society give recognition to this rank and the manner in which it was granted. Of course, nothing prevents a person from attempting to claim the identity of “sergeant”

without following the established procedure, but if the position is not legitimized by others, its name remains nothing more than an empty label.

On the other hand, in the case of

kimi

one of the factors which influence its appropriateness as an address term is age, of both the addressed person and the speaker. Age is the span of time from birth to the present moment, measurable in a very simple manner, making it one of the least ambiguous personal characteristics. To sum up then, although one might be under the impression that a verifiable status such as a military rank is something more tangible and concrete than the unverifiablekimi

, the former is without doubt a pure social construct, whereas the latter depends at least in part and in some cases on a fragment of prediscursive reality.And yet it is difficult to describe the relation between age and the use of

kimi

in precise terms. Generally speaking, it tends to be used by speakers11

older or similar in age to the person they are addressing, but the criteria are not so clearly defined that a straightforward mathematical rule for the use of this address term can be formulated.

This also applies to other age-based identities. Without formalizing the transition with some sort of “rite of passage,” it is not quite possible to pinpoint the exact moment when one stops being a child and becomes an adult, and then later becomes what is called a “senior citizen.” Such categories may sometimes have precise legal definitions, but those definitions do not always agree with the everyday language use. Furthermore, the adoption of the “senior citizen”

identity may be resisted, despite entering the age bracket generally associated with it. Each member of “The Rolling Stones” is above 60 at the time of writing, and yet they do not conform to the expected image of the elderly, perhaps because the identity of a senior citizen and of a rock star are not compatible with each other2.

So then, while social constructionism stresses – as the name suggests – the socioculturally manufactured aspect of identity, an anchoring of identity in tangible and measurable features of physical reality is still possible.

However, the criteria of deriving an identity from such features are not always precise or homogenous across individuals, and the stereotypes and expectations surrounding an identity do not necessarily logically follow from the character of its origin.

Identity can be more than merely constructed, it can be co-constructed.

This means that it is not only the individual in question that has a say in shaping it, but it can also be shaped by others. Deckert and Vickers (2011 : 9) note that in the sociolinguistic sense co-construction is not always achieved by cooperation. An identity can be imposed by others despite being rejected by the individual. An insult is a good example – intentionally labelling someone with an identity so undesirable that it can only be expected that the labelled (or should we say libelled) person will not accept it.

The desirability or undesirability of an attributed identity will be an important factor when discussing examples of the negotiation of identity in the

2 For an example of age-based identity being contested within a conversation see chapter 5.3.2

12

following chapter. The concept of positive and negative face as described by Brown and Levinson (1987) is strongly related. Positive face symbolizes the need a person feels to be approved by society. A compliment is understood as

“positive politeness” if it successfully affirms the traits that the addressee wants to see in herself. An insult threatens the positive face, because it is a challenge to the addressee’s identity. Of course, a compliment may backfire and offend the addressee. Conversely, what is construed as an insult may be gladly accepted by the recipient in some situations.

For example, pejorative terms for certain groups can be appropriated by those groups and stripped of their power to hurt. Perhaps one of the more famous examples is the retaking of the label

queer

by the LGBT community (Eckert and McConnell-Ginet 2013 : 224). In Polish, the wordciemnogród

is used to describe resistance to ideological and technological change, especially if the resistance stems from conservative religiosity, usually in the local context of Polish Catholicism. The word could be translated as “Darkville,” an imaginary place which the light of civilization has not yet reached. It is then clearly intended as derogatory, especially considering that “darkness” is used as a metaphor for ignorance and stupidity in other Polish words as well.However, Wojciech Cejrowski, a well-known media personality actually describes himself as

Ciemnogrodzianin

(“inhabitant of Darkville”) and does so with apparent pride. He even organized “Darkville Conventions,” gatherings for his fans and like-minded people (Newsweek Polska 2006). Furthermore, as a hardline Catholic he also appropriates the termkatol,

a shorter and offensively charged form of the wordkatolik

3.2.2.2. Gender

Robin Lakoff’s 1973 article

Language and Woman’s Place

is often referred to as the starting point for modern research on the relation between gender and language. Lakoff (1973) proposed a number of gender differences in language use, such as the frequency of tag questions. Her study was criticized for not providing sufficient empirical evidence, but has secured the status of an3 Compare to the word homosexual and the offensive homo. For more examples of superficially offensive but ultimately positively received expressions, consult chapter 4.

13 important milestone in the field.

Tannen (1990) suggested that the communication between men and women is in fact intercultural communication, and that misunderstandings which occur within it may be the result of differing values between the genders rather than ill will. Other scholars, however, disagreed with this view, claiming that the picture Tannen painted is too innocuous and the purported misunderstandings are the result of inequalities in power.

Butler (1990) challenged the concept of gender dichotomy itself, seeing gender as a performance, rather than an inherent quality. The poststructuralist view of gender as something constructed within discourse is prevalent today. The terms “gender” and “sex” were originally used to differentiate socio-cultural expectations and stereotypes concerning biological sexes from the sexes themselves. However, Butler claims that the concept of

“sex” is also a social construct.

The rejection of sexual dichotomy by Butler and others (e.g. Connell 2002) questions the validity of research on gender differences. Holmes (1997 : 217) says the following:

“In conclusion, then, recent research in language and gender clearly indicates the importance of focussing not on biological sex, nor even on the culturally constructed category of gender, but rather on the diverse realisations of the dynamic dimensions of masculinity and femininity.”

In this study, grouping the speakers into two broad categories of “men” and

“women” or “male” and “female” is performed on the basis of self-identification.

Both in the questionnaire and the online data from Facebook and blogs, the speakers had the opportunity to freely describe their gender, and almost all chose terms which permit placing them in either category. However, care is taken to demonstrate that women and men are not monoliths, by providing some examples in which gender is expressed in “diverse realisations” (mainly in section 3.1 and 4.1.1).

The terms “essentialism” and “constructionism,” as introduced in the previous section, are also meaningful when discussing gender. The question is:

are the differences in behavior, attitudes and norms between men and women

14

caused by biological innate traits, or are they molded through socializing? The review of literature by Cameron (2005) reveals that the latter view dominates in gender studies, although Cameron prefers the term “postmodern” to

“constructionist.”

This trend continues in more recent papers, as exemplified by Nakamura’s (2010) introduction to gender and language issues. Nakamura is strongly in favor of the constructionist approach, going so far as to claim that the associations between size and gender (big is masculine and small is feminine) are social constructions. But at least for the human race, males have measurably larger bodies than females, and one can suspect that this fact is the source of the associations. Of course, the ways of thinking derived from it may indeed be constructed, for example when they take the shape of normative judgments (“If you are not big enough, you are not a

real

man”), or when they are applied to non-human referents (“An imposing Hummer is more manly than a modest Mini Cooper”).The present study is a comparative one, but whenever two languages are put side by side for such purpose, there is a possibility that some features of one of them will not have an exact equivalent within the other. Grammatical gender in Polish and sentence-final particles as well as pronominal forms in Japanese are such features. Since they are directly related to issues of identity and gender, they deserve some explanation.

Similarly to several other Indo-European languages (e.g. French or German), in Polish gender is a grammatical category (Miemietz 1997). As a linguistic feature it divides words into distinct kinds which do not necessarily have anything to do with females and males (McConnell-Ginet 2014). In the Polish language, every noun in the singular is either masculine, feminine or neutral but only a small percentage of the real-world referents of these nouns have an identifiable sex and even if they do, in some cases it does not match the grammatical gender.

Człowiek

(“human”) is masculine butosoba

(“person”) is feminine regardless of the sex of the specific human or person that is being referred to.Dziecko

(“child”) is neutral, even though children are not sexless.However, many male forms of words pertaining to people are generic, they can refer both to males and females. The pronoun ktoś (“somebody”) is male, but of course the actual sex of the person is unspecified. Any mixed-sex

15

group of people is referred to in the masculine, while the feminine is typically only used when there are no males in the group. That is why grammatical gender in the Polish language has become a point of controversy on both linguistic and ideological grounds (Dąbrowska 2008). The male bias of the gender system motivates feminists to argue for language reforms.

While Japanese does not have grammatical gender, what it does have are lexemes which are strongly tied to a particular gender for pragmatic, not semantic reasons. Sentence-final particles like

wa

orzo

do not convey maleness or femaleness on the semantic level like the English words “actress” and “actor”or the Polish grammatical gender. Instead, they were traditionally thought to be used more often by speakers of one sex and this tendency was strong enough to cause a perceived dissonance when a speaker used a form which was tied to a different gender. These forms were not gender exclusive, however, as illustrated by the very fact that the other-sex usage mentioned above was common enough to elicit a response. The data on modern Japanese put to question the validity of the terms “men’s language” and “women’s language.”

Unlike the grammatical gender which cannot be ignored by Polish speakers, a user of Japanese can choose to avoid gender related words to a very large extent.

However, even if the speakers choose to do so for their own speech, the gender markers may be used as a tool to create personas for other people (see chapter 5 for further discussion on creating identities in quotations).

2.2.3. Culture

Takao Suzuki describes Japanese culture as one in which shame always plays an important role, unlike for example American culture, which according to his accounts shocked some Japanese with its casual nudity within groups of the same gender (Suzuki 1999 : 185). Restraint or liberality in exposing sexual symbols to others will become relevant when discussing linguistic taboos in Poland and Japan.

Wierzbicka (1985) contrasts the culture of Poland and that of Japan by putting them on opposite sides of physical expressiveness, with Poles being highly expressive and the Japanese relatively restrained. Another distinguishing feature of Polish is that it has the paradigm of grammatical gender for word categories like nouns, verbs, or adjectives. Since it forces

16

language users to make a choice between gendered forms in some situations, some scholars see it as more than a technical feature of language, but rather a mechanism for sexism (Dąbrowska 2008, Miemietz 1997).

17

Chapter 3

Creating and maintaining identity:

personal reference to others

Terms of personal reference, such as address terms, are understood here as any words that point to human beings through noting (or attributing) certain qualities or a certain status. In both Japanese and Polish such terms can describe the status of the addressed, whether objective social status (

poruczniku

“lieutenant,”omawarisan

“police officer”) or status relative to the speaker (ty

,omae;

both second person references the use of which is limited by social constraints). This can also be done in self-reference, especially in Japanese, which offers several pragmatically distinct first-person pronominal forms (ore

,boku, atashi

etc.). In Polish there is only one first person pronoun, but that does not mean speakers are completely deprived of choice in self- reference. For instance, a mother can call herselfmama

“mommy” in the third person instead of using the first-person pronoun, an approach which belongs to a system that uses only the child as a point of reference (see Dickey 1997 : 261).A historical example would be Polish kings using the first-person plural

my

(“we” in English) to refer to themselves, despite speaking as an individual and not a group. This was an honorific plural corresponding to thevous

of thetu/vous

diad used across Europe (see Brown and Gilman 1960). Not only can a speaker use self-reference as a form of expressing the identity, but also suggest an address term to be called by (“call me Bob”). In response to such a suggestion, the interlocutor can accept the suggestion, silently ignore it or explicitly reject it (“I don’t think that would be appropriate”).Any person can be called by a number of different terms, depending on the speaker, the social situation, the presence of others and so on. However, sometimes even for a single set of parameters multiple terms are available to the speaker. For example, in some Western households children use the name of the parents to address them, rather than a kinship name like “father” or

“mother.” For parents, both their given names and their parenthood are real aspects of their identity. The question is, which aspect is more important in the

18

context? Children may want to use a given name in order to avoid mentioning the asymmetrical and potentially hierarchical parent-child relationship. It would be a way to assert an egalitarian position. Alternatively, in the case of step-parents, the child may be reluctant to use a kinship term because she does not acknowledge the relationship as a familial one. The parents may accept whatever the motivations the children may have, but they may also decide that the parent-child relationship is

supposed

to be uneven and they may want to assert their position of power, or they may seek acknowledgement of their parental status for another reasons: as recognition of the emotional bond that ties the family. To see what adult speakers perceive as appropriate and desirable address exchange in the relationship with their children, refer to the survey results discussed in section 3.3.This chapter looks at terms that speakers used to refer to other people, whether the referent is the hearer or not. However, Braun (1988 : 11) treats the category of “address” (denoting hearer) as separate from “reference”

(denoting someone other than the hearer). Braun stresses the importance about making a distinction between address and reference due to their different functional properties. She gives the example of “grandson” as a term that is often used for reference in English, but rarely as an address term. This observation about the differences in usage is of course correct, but the act of addressing can also be seen as one of referring (in the second person), and so I treat the former as a subcategory of the latter. In any case, both kinds are equally relevant to identity management, the focus of this dissertation, and as such both will be studied, without ignoring the nuances between them if they become apparent.

3.1. Personal reference in blogs

The word “blog” is a contraction of “weblog.” In other words, it is a “log published using the Web.” A blog is a personal webpage on which the author posts entries concerning the topics of his or her choosing, such as: personal life, hobbies and interests, advice for the readers, etc. The distinguishing feature of a blog is its diary-like structure in which new personal entries are expected to appear from time to time, at least until the author decides to stop posting.

19

3.1.1. Communicating on a blog

A blog, being a platform located on the internet, is subject to some of the same limitations that define computer mediated communication (CMC) as a whole.

Crystal (2004 : 24) lists some of such limitations:

1) The characters available on a typing device limit the input capability 2) The dimensions and functionality of a display device limit reception

3) Both directions of communication are further affected by the constraints of the software and hardware that are utilized to enable connection to the Internet.

There are some forms of online communication which are not influenced by the limitations of a keyboards, e.g. voice chats. However, the linguistic exchange that takes place on a blog proceeds through written text and not speech. The exchange does not take place in real time, but rather at the convenience of the involved parties. When people take turns in a conversation, the pauses between those turns will be measured in seconds or fractions of seconds. The time that elapses between uploading a blog post and a response can be much more than that. There is no upper limit for it, and the exchange may in fact take place over the course of many years.

Furthermore, in live conversation the participants do not necessarily have set roles as far as managing the interaction is concerned. There are many examples of face-to-face interactions where speakers have distinct roles with distinct degrees of control over the interaction. But on a blog the owner is the one who has the right to initiate an exchange by proposing a topic, if he or she chooses to assume this sort of control. Depending on the features of a particular blog service, the blogger may also have the capability to moderate the communication act by removing inappropriate comments or blocking access for users who make such comments repeatedly. This is true for the celebrity blogs chosen for this study – anyone who wishes to make a comment is informed that the comment must be accepted by the administrator of the blog or it may not be published. Whether the blog is moderated by the celebrities themselves or a third party is not clear, but there are no visible sign of moderating activities.

20

On some online platforms a comment removed by the moderators will remain as a placeholder, but the message will be deleted. In some cases, the name of the offending user will remain visible and the cause of the inflicted penalty will remain on public record, as if to shame the violator and deter others from following his footsteps. However, no such obvious signs of the administrator’s judgment were found on the platforms selected for this study, which means that it is difficult to ascertain the number and character of deleted comments, if there were any. In any case, among those comments that were visible no inflammatory or even simply critical statements were found among the data.

This could be the result of covert moderation, but of course it is also possible that no users even attempted to post comments of such nature.

The celebrity blogs were chosen for several reasons. First, the celebrity status of the blog owners predicts a high number of comments under posts, due to the fame of the authors. This permits to accumulate a sufficiently large sample size, unlike blogs of a more obscure individual, which may attract only a few comments per post, or none at all. With fame as a first condition, another consideration was finding celebrities who manage their blogs on the same platform, so that the interface is held constant and doesn’t affect the results.

The progression of the exchange can also be very different from face- to-face interaction. On some blogs, each commenter not only refers to the post of the owner, but also to some comments that came before. This gives the communication act the structure of a long chain, which is similar to the structure of natural conversation. However, most of the comments gathered in this study referred only to the blogger’s post and not to preceding comments.

This means that the post and the comments formed multiple, independent and very short exchanges, rather than a single connected chain. The commenters communicated with the owner of the blog, but not with each other.

3.1.2. Self-presentation in “official blogs”

Currently, a blog can be both read and written by anyone with an Internet connection, including anonymous individuals. However, this study focuses on

“official” blogs written by authors with the status of a celebrity, widely recognized by audiences interested in popular culture. Internet blogs chosen here serve as a form of a diary for the celebrity. Of course, this is not a diary of

21

a traditional kind, one that is only intended to be seen by the person writing it, one used strictly for personal purposes. While the authors of the blogs write about a variety of subjects, including personal life, they are projecting an image of themselves as celebrities, through the lens of their careers. Their notes are not private introspections, but a presentation intended for the readers, who for the most part seem to be fans of the celebrities rather than friends or acquaintances. For a fan, the admiration for the idol’s work comes first, while the interest in the idol’s personal life only follows later.

The very name “official blog” hints that the blog belongs to someone who has achieved at least some fame, as it is used to separate sites administrated by fans of certain figures from sites maintained by those figures themselves or those who represent them. Each of the blogs listed below includes the word “official” in its title. This suggests that the celebrity’s name and the identity they are known for is a household brand in itself and that behind it is a network of managers and sponsors. Consequently, special discretion must be applied when divulging personal information on the blog, because it may affect not only the career of the blogger, but also of the blogger’s financial affiliates.

This is also true in the case of ordinary personal blogs, but to a lesser degree. Sakamoto (2010 : 6) reports that after a Japanese student drove a motorcycle under the influence of alcohol and talked about it on his blog, the university disciplined both him and the captain of his sports club (the student was drinking with his club colleagues). This is an example of consequences following from admitting involvement in an illegal and life-endangering act on a blog. A celebrity must take care even when divulging less controversial and non-incriminating information, because even such information may be enough to hurt his or her professional image, future career and income. An ordinary person has a smaller stake in maintaining a certain image, and always has the option to remain anonymous and avoid trouble. This makes an honest self- disclosure more likely, while a celebrity can be presumed to perform consciously selective self-presentation more often.

Even if the bloggers share only truthful information, the very act of picking one post topic over another gives them the first measure of control over the projected image. What is left unspoken sometimes has as much weight as

22

what is put into words. Whatever is verbalized will leave a very different impression depending on the exact words used. And many bloggers add images such as photographs to their post, which is yet another opportunity to adjust their self-presentation. This is most obvious when the picture is of the bloggers themselves – what is now known in the globalized lingo as a “selfie.”

Photographs are in themselves a material rich enough to deserve a separate study, but this section will also briefly touch upon the connection between the visual and the verbal.

As Erving Goffman (1959) showed in his seminal work, people engage in all sorts of performances on a daily basis and are not necessarily aware of it all the time. To use Goffman’s theatrical metaphor, the blog constitutes a “front region” or a “stage,” where the bloggers’ reflections on their daily life are only presented to the public after being subjected to a process of selection and refinement. Those parts of the bloggers’ lives which do not find their way to the blog remain in the “back region” or “backstage.” The difference between a blog and the examples given by Goffman in his book is that the blog is not a stage for a live performance, but a pre-recorded one. What the audience is allowed to see is an edited depiction of events, not the events themselves in real time. It is the difference between seeing a live theatrical play and a movie.

3.1.3. Personal reference as a response to self-presentation

The object of this study is not just the manner in which the celebrities present themselves in their posts, but also the way in which readers of their blogs respond in comments to said posts. Specifically, I was interested in finding out what kind of terms of address the readers use when referring to the bloggers.To use a term of address (e.g. “you,” “Sir,” “Jane” in English) is to make a direct reference to a person and such an act is strongly tied to the issue of personal image and identity. Address terms tend to be pragmatically charged, and neither Japanese nor Polish seems to offer a truly “neutral” term that one can use to refer to anyone in any context without ever causing some sort of

“trouble”– for example offending or confusing the addressee.Even the English

“you,” which is used much more broadly than any pronoun or pronominal form in Japanese or Polish and is generally safe when used as a second-person reference in a sentence can still be unacceptable when used vocatively to

23

attract the attention of people with certain status (“Hey you!”). Therefore, every time a commenter uses an address term he or she must make a choice which is based on the perception of the addressed celebrity and of the relationship between the two persons. The point I would like to make is that this choice is affected by the content of the blog entries – the commenters react to the blog owner’s self-presentation.

3.1.4. Japanese

This study is concerned with the self-presentation of four Japanese celebrities on their blogs and the verbal responses of their readers, specifically the address terms that the readers use to refer to the celebrities in their comments. The aim of this study is to investigate how the identities created by speakers affect address terms, in order to show that the manner of self-presentation, just like age or social status, is a factor in the address system. This section is based on an edited publication (Wolański & Matsumura 2014).

3.1.4.1. Blogs in Japan

The precursors of modern blogs started appearing on the Japanese internet around late 1990s. Since then the number of registered blog users has been steadily growing, reaching almost 27 million in 2009.4 Considering that the population of Japan is around 127 million, it would mean that almost twenty percent of Japan’s population was writing a blog at that time. This is a simplification, as there could be cases where one person has multiple blogs, or conversely multiple persons administrate a single blog, but the figure is sufficient as a rough estimate that shows the considerable popularity this medium has achieved in Japan. Incidentally, the figure of 20 percent is corroborated on a smaller scale by Sakamoto (2010 : 17). 20 percent of her university student respondents reported writing a weblog.

Because they are a fairly recent phenomenon, blogs have not yet been extensively studied in Japan. The studies that have been conducted are focused

4 Data gathered by the Institute for Information and Communications Policy, available at:

http://www.soumu.go.jp/iicp/chousakenkyu/data/research/survey/telecom/2009/20 09-I-13.pdf

24

on technological issues (Taniguchi et al. 2004) or psychological aspects of blog writing such as: the motivations that drive people to it (Yamashita 2005) or the self-disclosure aspect of writing about your personal life in a very public space that is the Internet (Sakamoto 2010). Yamashita proposes several research approaches to the study of blogs and mentions the possibility of a strictly linguistic study, but to the best of my knowledge none has actually been conducted in Japan so far.

The psychological studies mentioned above have some relevance to this study, but they analyze blogs created for non-commercial reasons, unlike the blogs chosen here. For the celebrity bloggers of this study internal motivations may of course be a factor affecting the decision to write (and continue writing) a blog, but another (possibly more important) factor is the potential publicity generated by the blog and the monetary gain that will follow.

The concept of self-disclosure used by Sakamoto applies more to the student bloggers whom she used as informants than the bloggers in this study.

The definition she uses describes self-disclosure as an act of self-expression where one openly tells another person true statements about oneself, in contrast to self-presentation, where one either tells true statements but does so selectively, or simply lies to make a certain impression. The latter concept is more useful when describing celebrity blogs. While there is no reason to think the authors of the blogs in this study are lying at any point, selective picking of the information to be divulged is surely taking place.

3.1.4.2. Data and methodology of this study

The data comes from blogs of Japanese celebrities hosted by Ameblo (ameblo.jp). It consists of comments made in response to some of the blog entries posted in March and September 2013. The most current entries at the time of data collection were used, regardless of the topic. A total of 200 comments were analyzed for each blogger. Those 200 comments were collected from several entries. Up to 50 comments from a single entry were analyzed, in order to avoid having too many comments from one source, which could create a bias in the data. This means that for every blogger at least 4 blog entries were analyzed.

25

The celebrities and their basic personal data are listed in the table below. These bloggers were chosen because when the first batch of the data was collected in March 2013, all of them were in the top 10 of the popularity ranking5, which means they received plenty of comments and so there was an abundance of linguistic material to work on. Furthermore, those two men and two women present different images of masculinity and femininity, and their popularity proves that each of those ways of being meets with some positive response in some parts of Japanese society.

Table 1: Japanese bloggers

Name Age6 Gender Profession Blog address

Momo 28 Female

Fashion and romance

guru

http://ameblo.jp/

momo-minbe/

Kintaro 32 Female Comedian http://ameblo.jp/

kintalotanaka/

Kenji

Darubishu 33 Male Musician http://ameblo.jp/

doramu-kenji/

Kensuke Sasaki 47 Male Wrestler http://ameblo.jp/

sasaki-kensuke/7

Momo’s job description in Japanese is

tarento

, or “talent.” This is a general term for people who sing, dance, act or do some similar kind of work in the entertainment industry. Her blog entries create an image of a feminine young woman who is knowledgeable in fashion, make-up and other forms of beautification. Momo is treated as a role model and a mentor by her predominantly female fans, who say they wish they could become as pretty as her and ask her for advice about beauty. She also receives many questions concerning romantic relationships with men. Momo seems to have a very loyal5 The ranking is displayed at http://ameblo.jp/

(Available as of 22 November 2013)

6 Age at the time of writing of the section in 2013.

7 As of 2017, Sasaki’s blog is accessible under a different address:

http://ameblo.jp/sasaki-kensuke-blog/

26

fan base – her blog is the only one which was still in the top 10 list of popular blogs in September 2013, ranking second place.

Kintaro is a comedian, which means it is her job to make people laugh.

“Cuteness” or “attractiveness” may be important for Momo, but these qualities are not central aspects of Kintaro’s persona. In fact, for comedic effect she often aims for “oddness” instead. The oddness begins with the name she chose for herself – Kintaro is a male name and its most famous bearer was a little boy from an old Japanese legend. She explains that she decided on this name after seeing it on a sign in a city she was visiting (possibly it was a name of a store or a restaurant). However, the choice was not completely random. She also stated on her profile that she named herself Kintaro because she wanted to become strong like a man and to succeed in the male dominated world of Japanese comedians. This further distances her from the typical femininity of Momo.

Kenji is a member of a rock band called

Gōruden Bombā

(Golden Bomber), which belongs to a subculture called “visual kei.” A common feature of this subculture is an androgynous image maintained by some of its participants. In fact, one of the most popular songs of the group is titled“Memeshikute,”

a reference to effeminacy. Kenji’s trademark is heavy makeup, mimicking that of actors in Kabuki theatric plays. Perhaps this is why in his profile5 he describes his gender as“kabuki.”

He also seems to be making an effort to control his body weight. He is not just trying to avoid obesity, but keeps his body very lean, if not thin. He is not married and does not have children, or if he does he keeps it a secret. His looks and his family status, combined with the playful tone he affects in many of his posts, create an image of a young boy rather than a mature man.Kensuke Sasaki is a wrestler. His work belongs to a genre called

puro- resu

(short for “professional wrestling”), which should not be confused with the competitive sport of wrestling which features in the Olympic Games.Puro-resu

is a scripted performance where the outcomes of the fights can be decided in advance and where entertainment is more important than athletic competition.The matches are performances and the wrestlers are performers, often adopting flamboyant personas which are sometimes based around a certain theme. Even when no particular theme can be found, one common

27

characteristic of most of the wrestlers is a macho hypermasculinity, represented by menacing expressions and poses as well as unusually muscular physique (wrestling performers are commonly more muscle-bound than athletes who participate in real combat sport competitions). This is the case with Kensuke, or at least it used to be. He is now in his late forties, raising his two sons with his wife, a fellow wrestler. He does mention his career from time to time and he maintains his brawn, but now family life seems to be the main topic of his blog posts. The aggressive fighting man gave way to the loving husband and father.

3.1.4.3. Results: cute Momo and quirky Kintaro

Table 2 below lists all distinct address terms that the two female bloggers received from their fans. Note that with the exception of one special case which will be discussed later, address terms which differed only in spelling were treated as the same unit. For example, some commenters wrote Momo’s name in

hiragana

もも and some usedkanji

桃, but it can be concluded from the context that this variation has little to no bearing on the pragmatic aspects of the address term.28

Table 2: References to Momo and Kintaro (detailed) Address to

Momo Number Address to

Kintaro Number

Momo-chan 210 Kintaro。san 49

Momo-san 14 Kintaro-san 46

Momo-tan 13 Kintaro 18

Moo-san 3 Kintaro。 8

Momo-chan-san 1 Kin-chan 6

Momoko-sama 1 Kintaro-chan 5

Kintaro。chan 3

Kin-san 3

Kintama 1

Kintaro-san 1

Total 242 Total 140

Momo received 242 address terms in total, more than one per every comment on average, the highest number among the four celebrities and considerably more than Kintaro, who was addressed 140 times. The meaning of this difference is not clear and it could be caused by chance, but such a high rate of address might be an expression of endearment. Jabłoński (2003) demonstrated that in everyday communication in Japanese it is quite feasible to do without address terms in a large proportion of utterances without negatively impacting the clarity of the message. Similarly, Yui (2007 : 25) notes that address terms appear in some Japanese sentences despite not being required to identify the addressee or get the addressee’s attention. In her opinion, this sort of seemingly redundant address serves as a sign of emotional closeness. Incidentally, the address term she uses in an example that illustrates her point is a first name combined with