An Empirical Study of the Effects of Pre-listening Activities on Listening Comprehension : -Basic Research to Enhance the Listening Proficiency of Japanese Senior High School Students

全文

(2) expedite listening proficiency, and that the. From this point of view as well, it is. benefits of vocabulary pre'teaching and. recommended to present visuals illustrating. question preview are actually a disservice to. the textual situation and its participants and. students.. naturally accompanying the utterances.. Given these findings' equivocality, we. Thirdly, it is inexpedient to spend too. are driven to reconsider the aim of pre"listening activity, to determine which of. much time at the pre-listening stage, because pre'listening activities boost. their forms are desirable. To increase. comprehension only temporarily, Spending. comprehension on the spot, vocabulary. too much time on pre'listening activities cuts. pre'teaching would be optimal. The aim of. into listening and post'listening periods,. pre'listening activity, however, ought to be. which are so essential in learning to listen.. not simply to aid comprehension temporarily,. Instead, we recommend a shorter. but to encourage students to tackle listening. pre'listening period, focusing mainly on. enthusiastically. Emphasized here is that. establishing the context and stimulating the. we should consider pre'listening activity in. incentive to listen. Allowing lots of time for. terms of students' progress in listening. listening and post-listening enhances. proficiency.. proficiency more than a lengthy pre'listening. Based on our findings, we explored how. period does,. best to use pre"Iistening activities to enhance. Finally, we propose the intermittent. listening proficiency. The chiefpropositions. delivery of shorter, sub'divided pre'listening. in this study are follows. Firstly, visual. phases. The first pre'listening phase helps. presentation, requiring students to predict a. students understand the environment and. listening text, should be considered the. tackle their listening work with enthusiasm,. nucleusofpre"Iisteningactivities. Thistype. capitalizing on visuals. If comprehension is. of activity is very efficient at motivating. lacking, subsequent pre'listening phases are. students to do listening work and. timed to alleviate problems as they appear.. understand the context of the listening text.. Additional pre'listening assistance is. As a result, students concentrate on the. supplied by degrees in the form of vocabulary,. listening work, thus improving their. background knowledge, comprehension check. listening pror}ciency.. questions and other necessary pre'listening. pre'listening stage is to be avoided. We. support. This sequence integrates the merits of the pre-listening activities. teachers tend to provide students with more. discussed in this study in a verified'effective. pre'listening assistance than is necessary, in. manner.. Secondly, excessive support at the. vocabulary, background knowledge, comprehension questions and other pre'text. information. But over'assistance prior to. lffregxg. iks firk. listening deprives students of the. re gxg. ?Npt espt....". opportunity to leam to listen and, through boredom, diminishes their desire to listen..

(3) An Empirical Study of the Effects of Pre'listening Activities. on Listening Comprehension -Basic Research to Enhance the Listening Proficiency. of Japanese Senior High School Students--. ta*4 • 3fittM2EftggJft. S'Hi.kTUi.i-Å~. M99456B N plz ?tli.

(4) An Empirical Study of the Effects of Pre'listening Activities. on Listening Comprehension -Basic Research to Enhance the Listening Proficiency. of Japanese Senior High School Students-. A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate Course at. Hyogo University of Teacher Education. In Partial Fulfillment ofthe Requirements for the Degree of. Master of School Education. by Hiroshi Takami (Student Number: M99456B). December 2000.

(5) i. Acknowledgements. This thesis could not have been completed without the. assistance and encouragement provided by numerous people. First and foremost, I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Hiroyoshi Jiju, my major supervisor, for his valuable. suggestions and sincere guidance at every stage of the preparation of this paper. His thoughtfu1 advice and constant support were indispensable for the completion of this paper.. I am profoundly gratefu1 to the Department of English. Language teaching staff of Hyogo University of Teacher. Education and to my fellow students for their helpfu1 inducement and hearty kindness.. I am indebted to the students of Kagoshima Prefectural. Sendai Senior High School who participated in the experimentation ofthis study. My gratitude is also extended to. my colleagues and the principal of the school for their warmhearted cooperation and encouragement. I acknowledge the generosity of the Kagoshima Prefectural. Board of Education for providing me with the invaluable opportunity to study in the Graduate Course of Hyogo University of Teacher Education.. I further wish to express my appreciation to Mr. Joseph. Doebele, who generously examined the entire draft and.

(6) ii. contributed to stylistic improvement, although any errors in this paper are my responsibility.. Last, but not least, I wish to thank my family, particularly. my wife, who has patiently supported and encouraged me all the time during these past two years. I could not have completed this thesis if it had not been for. the support and encouragement of these people.. Hiroshi Takami Yashiro, Hyogo. December 2000.

(7) iii. Abstract. The purpose of this thesis is to investigate the effects of. pre-listening activities on listening comprehension by Japanese senior high school students, and to explore which forms of pre-. listening activities are the most desirable in helping enhance listening proficiency. Despite the increasing importance given to pre-listening activities in L2 instruction, surprisingly little. empirical research has been done. Exactly what kinds of prelistening activities are the most effective and preferable remain. unknown. Four types of pre-listening formats are compared in this study: (1) question preview (Q Prev), (2) visual presentation (Visua}), (3) vocabulary pre-teaching (Voc) and (4) familiarizing. sound modifications (SM). These are the characteristic prelistening techniques in our classrooms. Experimentation was conducted on 196 high school students, employing materials from authorized English textbooks for Japanese high school students.. The data obtained from post-listening comprehension tests, follow-up tests and a questionnaire were statistically analyzed. with ANOVA and post hoc LSD testing. The analyses revealed these findings:. In post-listening comprehension tests, three methods (Voc,. Q Prev and Visual) enhanced comprehension above that found in the control condition, while SM did not contribute significantly..

(8) iv. Among the three effective types, Voc yielded the highest increases. The results were consistent regardless of the text type of the monologue or dialogue. As for effects on proficiency. levels, a notable discrepancy was clarified. While Voc was effective at all proficiency levels, the effectiveness of Q Prev was. restricted to upper- and middle-proficiency learners, and that of. Visual was confined to upper-level leamers.. Whereas vocabulary pre-teaching drastically facilitated listening comprehension, inexpediences with this format were. discovered through students' responses to a post-experiment questionnaire. Vocabulary pre-teaching does not enhance the incentive to listen; indeed, it is the method they least prefer.. Judging from motivational effects and student needs, visual presentation is the most desirable activity.. Follow-up tests showed no lasting effect from either monologue or dialogue materials, at any proficiency level. That. is, pre-listening activities only temporarily boosted. comprehension. For the Voc and Q Prev activities, comprehension fell considerably between post-listening and follow-up tests. These results imply that pre-listening activities. do not necessarily expedite listening proficiency, and that the. benefits of vocabulary pre-teaching and question preview are actually a disservice to students.. Given these findings' equivocality, we are driven to reconsider the aim of pre-listening activity, to determine which of.

(9) v. their forms are desirable. To increase comprehension on the. spot, vocabulary pre-teaching would be optimal. The aim of pre-listening activity, however, ought to be not simply to aid comprehension temporarily, but to encourage students to tackle. listening enthusiastically. Emphasized here is that we should consider pre-Iistening activity in terms of students' progress in listening proficiency.. Based on our findings, we explored how best to use prelistening activities to enhance listening proficiency. The chief. propositions in this study are follows. Firstly, visual presentation, requiring students to predict a listening text, should be considered the nucleus of pre-listening activities. This type of activity is very efficient at motivating students to do. listening work and understand the context of the listening text.. As a result, students concentrate on the listening work, thus improving their listening proficiency.. Secondly, excessive support at the pre-Iistening stage is to. be avoided. We teachers tend to provide students with more pre-listening assistance than is necessary, in vocabulary, background knowledge, comprehension questions and other pretext information. But over-assistance prior to listening deprives. students of the opportunity to learn to Iisten and, through boredom, diminishes their desire to listen. From this point of view as well, it is recommended to present visua}s illustrating. the textual situation and its participants and naturally.

(10) vi. accompanying the utterances.. Thirdly, it is inexpedient to spend too much time at the. pre-listening stage, because pre-listening activities boost. comprehension only temporarily. Spending too much time on pre-listening activities cuts into listening and post-listening periods, which are so essential in Iearning to listen. Instead, we. recommend a shorter pre-listening period, focusing mainly on establishing the context and stimulating the incentive to listen.. Allowing lots of time for listening and post-listening enhances proficiency more than a lengthy pre-listening period does.. Finally, we propose the intermittent delivery of shorter, sub-divided pre-listening phases. The first pre-listening phase. helps students understand the environment and tackle their listening work with enthusiasm, capitalizing on visuals. If comprehension is lacking, subsequent pre-listening phases are. timed to alleviate problems as they appear. Additional pre-. listening assistance is supplied by degrees in the form of. vocabulary, background knowledge, comprehension check questions and other necessary pre-listening support. This sequence integrates the merits of the pre-listening activities discussed in this study in a verified-effective manner..

(11) vii. CONTENTS Acknowledgements••'''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''•'''''' i Abstract''''•••••••'•••'''''''•••••••'''''''''''''''''''''iii List of Figures •••''''''''''''''••••••''''''''''''''''''''' ix. List of Tables •'''''''''•'••'•••••••••'••'''''''''''''''''' x. Introduction''''''''''''''''•••••••••••••••••••••••'•''''' 1. Chapter1 ListeningComprehension'''''''''•••••''''''''. 4. 1.1 ComponentsofListeningComprehension••••'•••''''. 4. 1.2 Nature ofthe Listening Process ''''''''''''''''''''. 5. 1.3 Difficulties Faced by Japanese Learners of English' ' '. 7. Chapter2 Pre-listeningActivityandLanguageLearning. ---e. 9. 2.1 Pre-listeningActivity••••••••••••••••••••••••e•. ee--. 9. 2.2 RationalesforPre-listeningActivity''''''''''''•. --e. 10. 2.3 Pre-liste ning Activities in Japane se Classrooms • '. --e. 12. Chapter3 RelatedResearche••••••••••••••eee••ee••••••e. 14. 3. 1 Experimental Studies on Pre-liste ning Activities • • e •. 14. 3.2 ExperimentalStudiesonPre-readingActivities'••••. 16. Chapter4 Experiment "ee-e--"----ee-e--e-e-ee--teeeee-4.1 Hypotheses''' te-----e-ee-eee--e-e"--eee--et-e-e-. 19. 4.2 Subjects''''''. eee-----e-e"e-e---ee-e"-e----"-----. 19. 20.

(12) viii. 4.3. Materials•••••••••'''••••••••••••••••••••••••••••. 21. 4.4. Instrumentation '''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''. 22. 4.5. Procedures ••••••••.•••••.••e.••.•••••••••••e••••. 24. 4.6. Results•'''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''. 26. Chapter5 Discussion •••''''•'••••••••••••••'••••''''''' 34 5.1 FacilitativeEffectsofPre-listeningActivitieson. Listening Comprehension''''''''••''''••''''''''' 34. 5.2 VocabularyPre-teachingvs.SchemaActivation''''' 35 5.3 Text [llype and Listening Proficiency''''••••••••••'' 37. 5.4 Problems in Vocabulary Pre-teaching '''••'•'•e••'• 39. 5.5 Pre-listeningActivityandEnhancingListening Proficiency '''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''' 42. 5.6 Summary''''''''''''"''''''''''••••••••••••••••• 45 Chapter6 Paradigm forPreferable Pre-listeningActivity ••. 47. 6.1 Perspective'''''''''''''•''''''•'••••••••••••••••. 47. 6.2 Emphases''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''•''•'. 48. 6.3 Contents '''''''''''''''''''•••••••••••••••••••••. 49. 6.4 TimeAllotment '''''••••••••••e••••••••••e••••••e. 50. 6.5 Notabilia ''''''''''''''''''''''''•••••e•e•ee••ee•. 51. 6.6 Example•••••••••••••••••••e••••••••••••••••...... 51. Conclusion'''''''''''''e'''•e-•••••••e•••••••••••••••••• 56. Bibliography'''''''''''''''''••'''''•••••••••••••••••••• 60.

(13) iX. Appendices '•. ---. •••••••-e••'••'''''''''"'''''''"'''' 66. Appendix. 1. Entry Test ''''''''''''''''''''''''''''' 66. Appendix. 2. Data of Entry Test and ANOVA Summary ' 67. Appendix. 3. Listening Material'''''''''''''''•'•'•'' 69. Appendix. 4. Warm-up Sheets '''''''''''''''''''''''' 70. Appendix. 5. Post-listening Comprehension Tests ' ' ' ' ' ' 74. Appendix. 6. Questionnaire '''•••••••••••••••••••••'' 75. Appendix. 7. Cross Table ofQuestionnaire Responses '' 77. Appendix. 8. ANOVA Summary and Post Hoc Comparison on Post-listening Comprehension Tests ' ' ' 81. Appendix 9. ANOVA Suminary of Follow-up Listening Comprehension Tests ''•'''''''''''''''' 83. Appendix 10. ANOVA Summary and Post Hoc Comparison on Motivational Effects of Pre-listening. Activities ''''''''''••••'''''''''•''••'' 84. Appendix ll. ANOVA Summary and Post Hoc Comparison on Students' Favorable Impressions toward Pre-listeningActivities'''''''''''''''''' 86. Appendix 12. Listening Material and Comprehension-check Questions for Example •••e••••••••e••••• 88. Figures. Figure. 1. Components of Listening Comprehension ' . • '. 5. Figure. 2. Information Sources in Comprehension ''''''. 6. Figure. 3. Deficiency of the Experiment in Berne (1995). 16. Figure. 4. Diagram of Experimental Design '''''''''''. 26.

(14) x. Figure 5. Mean Scores on Post-listening Tests '''''''' 28. Figure 6. Mean Scores by Listening Proficiency on Post-listening Tests ''''''''''''''''''''''' 30. Figure 7. Mean Scores on Follow-up Tests '''''''''''' 32. Figure 8. Comparison of Mean Scores on Post-Iistening and Follow-up Tests ••t••••••••''''''''•''' 33. Figure 9. Motivational Effects of Pre-listening Activities. ..........."..".......••••••••••••••••• 40 Figure1O. Favorite Impressions of Students toward PreIistening Activities '''''''''''''''''''''''' 41. Tables. Table 1. Data of Entry Test •''''''''••e••••'•••••'•••• 21. Table 2. Data of Combined Scores on Post-listening Tests. ••••••••-•••-•••••••••••••••••••••-••••• 27 Table 3. Data from Two Kinds ofPost-listening Tests ' • • 28. Table 4. Data of Combined Scores by Listening Proficiency on Post-listening Tests e••e••••••••••••••••••e 30. Table 5. Data from Follow-up Tests•••••••••e•••••••••e 32. Table 6. Comparison of Post-listening and Follow-up Tests. •••••••••••••-•••--••--•••••••••••••••• 33 Table 7. Motivational Effects ofPre-listeningActivities • 40. Table 8. Favorable Impressions of Students toward Pre-listeningActivities•••••••••••e••••••••••e 41. Table 9. Advantages of Pre-listening Activities e••••••e• 45.

(15) 1. Introduction. In Japanese classrooms of English instruction, nurturing. `practical communicative competence' is a crying need. Although speaking is primarily associated with this type of competence, listening should be considered equally important,. since communication will break down if the listener fails to. comprehend the speaker's intention. Although we can manage. to express our ideas at our own pace in speaking, we are frequently at a loss in listening because we usually cannot control the manner or pace of the speech we are trying to follow.. Listening comprehension is a basis of successfu1 communication. The specific and effective measures for teaching listening,. however, are unsettled, as Sano (1992) and Kumai (1997) have observed. The new Course of Study, which is to be enforced in. the 2002 academic year, all the more emphasizes the development of listening skill. At present, the question of how. to enhance the listening proficiency of Japanese students of English remains unanswered. A three-staged procedure (pre-listening, while-listening and. post-listening) for teaching listening, advocated by Underwood (1989), has gradually infiltrated into our situation. Although. the conventional listening-teaching method was strongly criticized as testing rather than teaching (Richards 1983, Sheerin 1987), pre-listening and post-listening activities can be a.

(16) 2. remedy for the criticism. The teacher should provide students. with appropriate support and guidance at pre-listening and post-listening phases because teacher intervention is virtually impossible during the students' listening time.. According to this sequence, the author has conducted prelistening activities under a belief in the importance of activating. students' schemata: before listening, they are to guess the contents of the listening text through pictures and titles; they are. to talk about the topic; or they are provided with an outline ofthe text through oral introduction, and so forth.. Through my experience in the classroom, however, several questions arose concerning pre-listening activity. What kinds of. activity will be the most effective among the various forms of. pre-listening activities? Is vocabulary instruction really inefficient for increasing comprehension, while activating students' schemata prior to listening is highly recommended? Does the efficacy of pre-listening activities vary according to. learners' listening abilities or listening materials? These questions are the starting point of this study. Another concern. is whether or not students' listening proficiency is developed through the pre-listening activity. It is probably true that their. comprehension is temporarily facilitated by this kind of. preparatory work, and the teacher feels comfortable in conducting lessons. Nevertheless, students are expected to comprehend the spoken discourse without the assistance of pre-.

(17) 3. listening support outside the classroom. The question remains as to whether or not this contributes to students' progress in listening proficiency.. Despite the increasing importance given to pre-listening. activities, surprisingly little research with the support of. empirical data has been found in this area. This thesis attempts to examine, from various perspectives, the efficacy of. different forms of pre-listening activities on listening comprehension by Japanese senior high school students.. In the next chapter, we overview the general concept of listening comprehension before turning to a close examination of pre-listening activity. In Chapter 2, the nature of pre-listening activity is clarified as a premise of this research. Chapter 3 is. devoted to the precedent-related research. The findings and deficiencies of that research are presented as the basis of the. present study. In Chapter 4, the experimental scheme and obtained results are described. In Chapter 5, we discuss the results along with implications for the classroom, and we explore the desirable ways to employ pre-listening activities for Japanese. high school students. The discussion is extended to Chapter 6,. in which a paradigm for preferable ways to employ these activities is proposed in our situation. Finally, this research is. summarized, with the direction of further study discussed in conclusion..

(18) 4. Chapter 1. Listening Comprehension. In the past, Iistening was frequently characterized as a passive or receptive skill in which the listener just Iistens to the. sounds through the ears. Today, listening is generally recognized as an active and conscious process that requires the listener's active participation. Before entering directly into an. examination of pre-listening activity, we should look briefly at the general concept of listening comprehension.. 1.1 ComponentsofListeningComprehension According to Longman Dietionary ofLanguage Teaehing ({} App7iedLinguistics (1992), listening comprehension is defined as. "the process of understanding speech in a second or foreign. language" (216). For the listener to understand utterances successfu11y, complex processes are involved. Rost (1991) points out the following component skills of listening: 1. discriminating between sounds. 2. recognizing words 3. identifying grammatical groupings ofwords 4. identifying `pragmatic units '- expressions and sets of utterances which. function as whole units to create meaning 5. connecting linguistic cues to paralinguistic cues (intonation and stress). and to non-linguistic cues (gestures and relevant objects in the situation). in order to construct meaning 6. using background knowledge (what we already know about the content and the form) and context (what has already been said) to predict and.

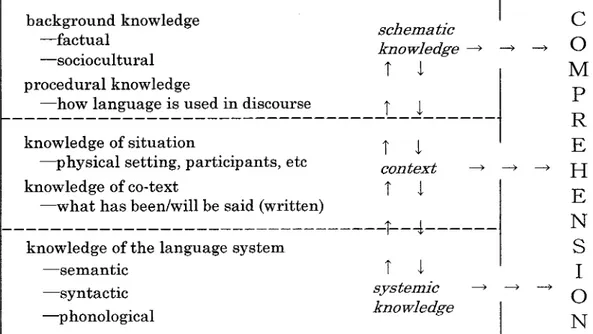

(19) 5. then to confirm meaning 7. recalling important words and ideas. (3-4). Rost regards the integration of•specific. skills as a person's. listening ability, as shown in Figure 1.. Pereeption skills. Analysis skills. Synthesissin71s. Discriminating sounds Recognizing words. Identifying grammatical units Identifying pragmatic units. Connecting linguistic and. other cues Using background. know}edge Recalling important words. and ideas. LISTENING ABILITY Figure 1. Components of Listening Comprehension (Adapted from Rost, 1991: 4). In listening, we interpret the meaning of what we hear by. integrating these subskills. Furthermore, this process must. occur immediately because sounds disappear instantaneously and the flow of new information is constant.. 1.2 Nature ofthe ListeningProcess. From the standpoint of information processing and psychological Iinguistics, listening comprehension is generally. recognized these days as an active and conscious process in which the listener constructs meaning by mobilizing all of his multiple resources to verify his prediction (Anderson and Lynch. 1988, Rost 1991, Koike 1993, Nunan 1998, Futatsuya 1999)..

(20) 6. The sound input to which the listener attends is segmented and. interpreted in collation with linguistic and background knowledge stored in long-term memory. Anderson and Lynch (1988) present an intelligible model of the complex listening process, as shown in Figure 2.. ;ackground knowledge ' ehematie fffactual -sociocultural. C. knowledge- ->. nt. TS i. M. 2r.f:-IX-2-".r-a,a.-k,"-.O-.W,18iEge!,-e-d2n-d--iEc-o!r-sg------T---J------l. knowledge of situation T s 1 knowledge ofco-text T l -what has beenlwill be said (written) -physicalsetting,participantS,etC eontext -> -. ---.------------mm-m-.-----------knowledge of the language system. T--------m. -syntacticknourledge systemle ... -phonological. Figure 2. Information Sources in Comprehension. .o. P R E -> H E N s I. N (Andersonand Lynch,. 1988: 13). In interpreting what we hear, we construct a meaning on. the basis of our own knowledge of vocabulary, grammar and phonology as though it were piling up from the bottom as shown in the figure above foottom-up processing). We also attempt to. comprehend what we hear with the clues provided by our own prior knowledge and experiences outside the text (top-down processing), which are also shown in the figure. In listening comprehension, both bottom-up and top-down processing seem to.

(21) 7. be utilized interactively and compensated reciprocally. Ifa topic. is familiar to the listener, he is capable of supplementing and. predicting the contents of the utterance by taking good advantage of schema effectively even when only fragments of the. words and phrases are actually heard. This is probably evidence that those who are not proficient in English nonetheless. manage to understand speech pertaining to fields they know. To conclude, listening comprehension, involving both bottom-up and top-down processing, is a highly integrated and complex process.. 1.3 Difficulties Faced by Japanese Learners of English. Yamauchi (1997) points out knotty problems that Japanese learners of English tend to have in listening comprehension: 1. Iarge quantity of information beyond processing capacity. 2. inability to recognize sound changes in spontaneous English speech 3. failure to identify English words by differences in acoustic images. 4. Iimited vocabulary and grammatical competence. 5. insufficiency ofbackground knowledge 6. banefu1 influence of translating word by word 7. deficiency in grasping outline and main points 8. Iack of interpretative competence in native language 9. psychological barrier (12-13). Among these factors, 1 to 4 involve bottom-up processing, while 5. to 7 relate to top-down processing. As students frequently complain, problems in bottom-up processing seem to be a more. serious hindrance than problems in top-down processing for.

(22) 8. Japanese learners.. Nishino (1992) investigated the correlation between listening comprehension performance and six relevant factors:. (1) speech perception; (2) recognition vocabulary; (3) grammatical knowledge; (4) background knowledge; (5) shortterm memory and (6) logical inference. The results indicated that vocabulary recognition has the highest correlation (.41. to .54) with listening comprehension performance. He argues that vocabulary recognition is a decisive factor for successfu1. listening comprehension for Japanese learners, although background knowledge and speech perception are also good predictors of Iistening comprehension. This experimental study implies that listening comprehension may be most facilitated by preparing the learner for better vocabulary recognition.. The term "vocabulary recognition" here refers to the listener's ability to connect the sound of a word with its meaning.. In addition to the listener's lexical ignorance, the difference in. the acoustic image between his pronunciation and that of a native speaker causes the learner's failure to recognize words he. already knows. Sound modifications appearing in spontaneous speech also impede vocabulary recognition: "Soup or salad?" or "I will ask her" are misinterpreted as "Super salad?" or "Alaska"..

(23) 9. Chapter 2 Pre-listening Activity and Language Learning. Vandergrift (1999) argues that "Pre-listening activities are. crucial to good second language pedagogy" (172). If students were forced to listen to a material without any preparation in the L2 classroom, they would not only fail to listen successfully, but. also find the task absolutely uninteresting. The reason for this is that they are required to listen to a passage or a conversation. that is irrelevant to them, without any expectation or purpose. In this chapter, the nature of this activity should be reviewed as a premise of this study.. 2.1 Pre-listeningActivity The concept ofpre-listening activity is not new. The most important contribution in this area has derived from Underwood. (1989). She consolidated the nature of this activity systematically, relating theoretical perspectives to practice. By her definition, pre-listening activity is described as follows:. ... before Iistening, students should be `tuned in' so that they know what to. expect, both in general and for particular tasks. This kind ofpreparatory work is generally described as `pre-listening work' or just `pre-listening'..... The words `activity/activities' are used throughout this book to embrace the whole variety ofthings that might be done, in the classroom or outside it, in relation to listening texts (30-31).. There seems to be general agreement among scholars and.

(24) 10. teachers on the definition of pre-listening activity. This paper. also uses the term to mean an activity conducted prior to listening, that orients the learners to what they are about to hear and provides some task that is relevant to the listening text, as is. generally approved.. As regards specific examples, Underwood refers to the following: - looking at pictures and talking about them; - looking at a list of items, thoughts, etc.; - making lists ofpossibilities, ideas, suggestions, etc.;. - reading a text; - reading through questions (to be answered while listening); - labelling a picture; - completing part of a chart;. - predictinglspeculating; - previewing the language which will be heard in the listening text; - informal teacher talk and class discussion. (35-43). It is clear from these examples that pre-listening activities. embrace various types of activities related to a particular listening text. Despite the range ofthe above, Underwood does. not mention which kinds of activities are more effective or preferable than others at the pre-Iistening stage. Had she done. so, the present study might not have been undertaken.. 2.2 RationalesforPre-listeningActivity Why is pre-listening activity required prior to listening? To sum up the assertion of Underwood (1989), the following roles.

(25) 11. are specifically described as the significance of pre-listening actlvlty: a. to focus the learners' minds on the topic by narrowing the range ofwhat they expect to hear and activating their relevant prior knowledge;. b. to augment linguistic and background knowledge if students' own knowledge is insufficient; c. to contextualize the texts and to make the listening work realistic;. d. to make the work purposefu1; e. to remove the stress of suddenly hearing something, thereby enhancing their motivation for listening; f. to help them concentrate on the task, and afterwards, to give them a comforting sense of having achieved the objective, which in turn acts as a motivating force on future occasions. (30-44). The significance pointed out by other scholars overlaps the. rationales above (Anderson and Lynch 1988, Ur 1991, Oxford. 1993, Harmer 1994, Mendelsohn and Rubin 1995, Kumai 1997, Vandergrift 1999). The theoretical background ofthe rationales. reflects recent outcomes in applied linguistics. To make the Iistening work in the classroom more realistic and meaningfu1, information that tells a Iistener why he is listening and what to. expect are emphasized. The context of a listening text, such as information about the situation and speakers, should be given to. students to get them to learn language in context. In terms of affective view, that is, the subjective point of view of the learner,. importance is also attached to motivation and a comforting sense. of success in learning. Not the product but the process of constructing messages from spoken language, utilizing various.

(26) 12. information sources, is regarded as noteworthy. The rationales for pre-listening activity are especially influenced by schema. theory, in which the more background knowledge the listener possesses, the more comprehensible the listening work will be.. Prior to listening, and reading as well, inducing schemata of learners is highly recommended. 2.3 Pre-listeningActivitiesinJapaneseClassrooms The author of this thesis examined all of the 17 textbooks. on 0ra7 Communieation B presently published in order to determine what kinds of pre-listening activities prevail in our. situation. Most of the textbooks institute tasks prior to listening, under the headings "Warm-Up", "Get Set" or "Before Listening". In the textbooks that do not set up such tasks, it is possible for teachers to conduct pre-listening activities utilizing. pictures, vocabulary lists, titles or other helpfu1 resources contained in the textbooks. This examination of the types of pre-listening activities in. the textbooks revealed that the following four types are consplcuous:. 1. to predict the contents of a listening text, presenting pictures or photographs. 2. to familiarize students with new words and expressions in the listening text 3. to present listening points by delivering questions. 4. to familiarize students with phonological modifications in.

(27) 13. English. The first and third types, by leading listeners to focus on the. passage as a whole rather than individual words or structures,. are considered to encourage a more top-down approach to processing passage content. In contrast, the second and last. types of activities are regarded as encouraging bottom-up processing, by leading listeners to focus on individual words rather than the passage as a whole.. Among the four types referred to above, familiarizing students with phonological modifications is not included in Underwood (1989). The reason for this is probably that many Japanese researchers argue that linking, reduction and other phonological modifications in spontaneous speech are the main. obstacles to Japanese learners' listening comprehension (Miyamoto 1977, Shimizu 1983, Noda 1991, Yamada, Adachi and ATR Ningenjyohou tsushinkenkyujyo 1998). Even if pre-listening activities are administered either in. the native language, Japanese, or in the target language, English, the activity types can fall into those four general. groups. The four characteristic pre-listening techniques prevailing in our classroom are to be adopted as experimental groups in this study, which will be touched on later..

(28) 14. Chapter 3 Related Research. In this chapter, related research is presented to clarify. what has been verified and what remains to be answered. On the effects of pre-listening activities, very little research was. found. Accordingly, it would be beneficial to expand the field into research concerning pre-reading activities, in which a large. number of studies have groped for effective pre-reading actlvltles.. 3.1 ExperimentalStudiesonPre-listeningActivities Berne (1995) states that "no empirical research has been found to date which compares the effects of different types of pre-listening activities on L2 listening comprehension" (316).. In our country, however, a chain of research by Takefuta and others attempted to clarify the effects of pre-text information. (Takefuta et al. 1988, Takahashi et al. 1988, Ishikawa and Takefuta 1988, Takefuta 1989). Takefuta (1997), recapitulating these experimental studies, alleges that the effect of pictorial. information is a 30-percent increase, that of vocabulary is 61 percent, and that of learning sentences is 75 percent. Although. these experimental studies verify that pre-text information contributes to listening comprehension, the numerical values. shown above cannot be accepted without reserve because they. derive from different materials and from several separate.

(29) 15. experiments. In all the experiments but one (Ishikawa and Takefuta 1988), the materials employed are not discourses but sentences, which are far from real-life listening. Furthermore, it seems dubious to say that listening to a passage after students have already learned all the sentences in it, is a "listening work".. Berne (1995) compared the relative effectiveness of two different types of pre-listening activities: (1) "question preview",. which consisted of studying the questions and possible responses in the post-listening comprehension test; (2) "vocabulary", which consisted of studying a list of 10 key words from the passage and. their equivalents. The results revealed that only subjects completing a question preview received significantly higher scores than a control group. Contrary to Berne's assumption, the scores of the vocabulary group fe11 short of those of a control. group, although no significance from this emerged. She concluded that vocabulary instruction did not facilitate listening. comprehension, and that instructors were better off employing pre-listening activities that encourage a more top-down approach. to processing passage contents than those that encourage bottom-up processing. This position seems untenable for several reasons. First, the treatment of each experimental group, as can be illustrated. in Figure 3, does not seem fair. The question preview group considerably obtained the right answers to the post-listening multiple-choice comprehension test before listening, because the. students were furnished not only with the questions on the test.

(30) 16. but with the answer options. The vocabulary group, in contrast,. was supplied only with 10 words without sound presentation or. phonetic symbols among 862 words in a passage. Second, the. homogeneity of the groups was not confirmed before the experiment. There is a possibility that the control group was originally superior to the vocabulary group. Third, in the case. ofJapanese learners of English, vocabulary pre-teaching may be. facilitative, as Nishino (1992) indicated that it is the most serious obstacle for Japanese learners. Fourth, it is too hasty a. conclusion to say that pre-listening activities that encourage. top-down processing are more desirable than bottom-up types,. based simply on the comparison between question preview and vocabulary. To determine the relative efficacy of pre-listening. activities, it will be necessary to compare more experimental groups of different pre-listening formats. Pre-listeningActivity Access to the Contents ofListening Text. Questionpreview Figure 3. Deficiency ofthe Experiment in Beme (1995). 3.2 ExperimentalStudiesonPre-readingActivities Unlike the scarcity of studies on the effects of pre-listening. activities, a vast amount of scholarship has been devoted to the. effects of pre-reading activities on L2 reading comprehension.. The pre-reading activities adopted in these studies have been.

(31) 17. quite diverse: visual presentation and vocabulary Iearning (Hudson 1982); outline presentation (Tudor 1986); summary and pre-questions ('IhJtdor 1988); pre-questioning, pictorial context. and vocabulary teaching (Taglieber et al. 1988); presenting an. illustration and vocabulary teaching (Akagawa 1992); and oral. introduction and vocabulary prediction (Mochizuki 1992). Furuya (1993) summarized the results of these experimental studies as follows: 1. Pre-reading activities are effective for reading comprehension of text in all their different types.. 2. Tasks for top-down processing (presenting visuals, question preview and outline presentation) are more effective than tasks for bottom-up. processing (vocabulary teaching). 3. Pre-reading activities are especially effective for Iow-level Iearners, for. such learners with little prior knowledge fail to draw relevant clues and information from the context. (59). Shizuka (1994) raised an objection against the commonly accepted assumption that top-down processing is more efficient. than bottom-up processing. He stressed that the vocabulary instruction in the aforementioned research was insufficient and/or inappropriate, reexamining the relative effectiveness between schema activation by illustration and vocabulary preteaching. He compared "the condition with plentifu1 forecast of the listening text, inducing relevant schemata on conscious level,. in spite of insufficient vocabulary knowledge" with "the one with. almost complete understanding of the meanings on vocabulary in. 'il'.

(32) 18. the passage without prediction of the passage." The results of. the post-reading comprehension test, which were obtained from. Japanese senior high school students, demonstrated that the vocabulary group performed significantly better than the schema group regardless of the learners' proficiency levels.. Based on these findings, he suggested that the instructor. should exert himself to improve learners' language ability. through, for example, vocabulary instruction, rather than providing the learners with schemata. Nevertheless, there is a. possibility that both the vocabulary and schema groups might have had significant treatment effects, since a control group that. performed no pre-reading activity was not instituted in this. experiment. If he had compared the three groups, the characteristic of each pre-reading format would have been cle are r.. In addition to these somewhat conflicting results, there are. distinctive differences between L2 reading and listening comprehension (Lund 1991, McDonough and Shaw 1993). With the aforementioned lack of data on the effects of pre-listening. activities, it remains a challenge to compare the efficacy of different forms of pre-listening activities. The present study was undertaken on the basis of the findings and shortcomings of. this precedent body of research. The experimental scheme of this study, which is described in the next chapter, was designed with reference to these experimental studies..

(33) 19. Chapter 4 Experiment. The purpose of the present study is to compare the efficacy of four different types of pre-listening activities, which as stated. in 2.3 have been in wide use in the Japanese classroom, on comprehension by Japanese senior high school students using textbook-level materials. The experimental groups are called. Question Preview (Q Prev), Visual Presentation (Visual), Vocabulary (rVoc) and Sound Modifications (SM), the treatment of. each ofwhich is detailed in 4.5. '• Specifically, this study attempts to answer these questions:. 1. Is vocabulary pre-teaching surely ineffective for listening. comprehension?. 2. Which is more effective for listening comprehension, vocabulary pre-teaching or schema activation by visuals? 3. Does the efficacy of pre-listening activities vary according to. the listening materials? 4. Does the efficacy of pre-listening activities vary in relation to. learners' listening proficiency?. 5. Do pre-listening activities lead to the improvement of Iearners' proficiency in listening comprehension?. 4.1 Hypotheses The following hypotheses, correspondent to each research.

(34) 20 question, are posited:. 1. Regardless ofthe form that the activity takes, pre-listening activities facilitate listening comprehension.. 2. Vocabulary pre-teaching is a more facilitative technique for. the comprehension by Japanese senior high school students than schemata activation by visuals.. 3. Effective types of pre-listening activities are the same, whether the material used is a monologue or a dialogue. 4. Effective types ofpre-listening activities vary in relation to subjects' L2 listening proficiency.. 5. Pre-listening activities lead to improvement in the listening proficiency of learners.. With regard to Hypothesis 1, there is no consensus of opinion. As regards Hypotheses 2 to 5, no research exists to the best of my. knowledge.. 4.2 Subjects The subjects for the study were 196 students in total from. five classes of first-year students of a Kagoshima prefectural. senior high school. Their English proficiency roughly corresponded to the lower-intermediate levels. In Shinken Moshi held in June 2000, their nationwide deviation score from. the average mark was 50.3 (range: 72 to 32). They are thought to be representative of high school students in Japan.. In advance of the experiment, the homogeneity of the five. classes was confirmed by a listening comprehension test (F(4,.

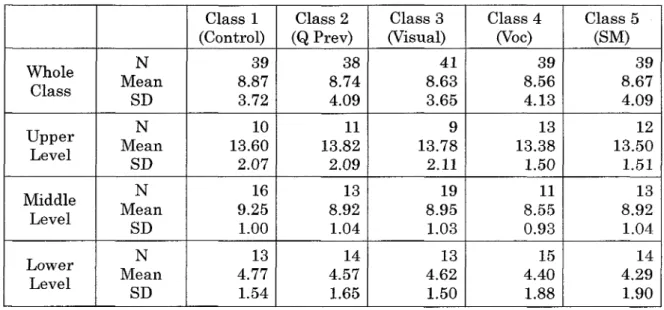

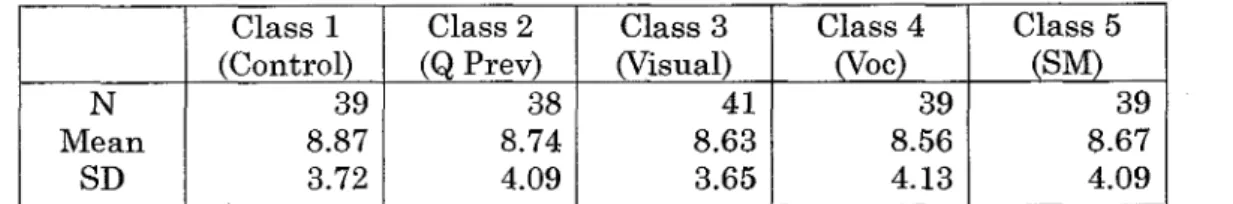

(35) 21. 191) = O.034, n.s.). This entry test, which is presented in. Appendix 1, was extracted from Zen-ei-ren (1981) which was designed to be standardized for Japanese senior high school students. The data of the entry test appear in Table 1, and the details can be seen in Appendix 2. Table 1. Data of Entry Test. 39. Class2 (QPrev) 38. 8.87 3.72. 8.74 4.09. Class1 (Control) NMeanSD. Class3 (Visual). 41 8.63 3.65. Class4. CIass5. SM). oc). 39. 39. 8.56 4.13. 8.67 4.09. Based on the scores of this listening test, the subjects of each group were split into three proficiency levels: Upper (score. 14 to 18), Middle (8 to 12) and Lower (O to 6). As presented in Table 3 ofAppendix 2, there were significant differences (p<.OOI). between these three subject levels. The homogeneity of each level in the five classes was also confirmed, as indicated in Table. 2 of Appendix 2. Thus, the five groups were ascertained to be equivalent in their listening proficiency.. Class 1, which had the highest average score, was devoted as the control group, although the difference was slight enough to be insignificant. Each ofthe other four classes was randomly assigned to one of the four experimental conditions (cf. Table 1).. 4.3 Materials Two listening texts, both of which were extracted from textbooks of 0ra7 Communieation Bthat the subjects did not use,.

(36) 22. were employed in the experimentation (cf. Appendix 3). Material 1 which consists of short announcements aboard an ' airplane, is a monologue of 129 words. Material 2, which is in. interview form, is a dialogue of 144 words. In both cases, the cassette tapes accompanying the textbooks, which were recorded by native speakers of English, were used. The tape speed of the. both materials was estimated at 150 words per minute. The questionnaire after the experiment indicates the appropriateness of the materials: 43.90/o of the subjects regarded the materials as. neither difficult nor easy; 34.20/o regarded them as a little difficult.. 4.4 Instrumentation. Warm-up sheets were prepared as handouts for prelistening activities (cf. Appendix 4). Deliberate care was taken. so that each handout was equal in accessing the contents of the listening text. The final version was completed after the review by experienced English teachers with considerable modifications.. Warm-up sheet A for the Q Prev group indicates only the listening points of a post-listening comprehension test, excluding. choices, so as to reexamine Berne (1995). Warm-up sheet B for the Visual group contains pictures indicating the situation of the. listening text. This sheet, after the model of Shizuka (1994), does not include the information for which the subjects directly. listen. Warm-up sheet C for the Voc group consists of a list of.

(37) 23 unknown words and expressions with their Japanese equivalents. As for selection of the vocabulary, all the words and idioms were listed in Taish ukan 's Genius English-Japanese Dietionary (2000). as unlearned in junior high school. The words are arranged in. alphabetical order so that they prevent the subjects from predicting the listening text through the vocabulary presented.. In Warm-up sheet D for the SM group, the phrases or sentences that include all the phonological changes appearing in the texts,. that is, juncture, elisions, assimilation, contractions and weak forms, are collected for partial dictation.. Post-listening comprehension tests were developed respectively for Materials 1 and 2 (cf. Appendix 5). The questions were confined to the outline and vital points of the. listening text. To avoid confounding subjects' listening comprehension performance with their L2 reading ability, their native language Japanese served as the language of assessment.. The reason for adopting an open-end question format, rather than multiple-choice, was to avoid accidental success and to discern comprehension performance more minutely. In addition to the tests, a participant questionnaire was prepared to obtain other information to help interpret the data. (cf. Appendix 6). This questionnaire dealt with Iistening comprehension tests (difficulty, obstacles for listening, the way of. listening) and pre-listening activity (motivation, validity for listening, interestingness, time allotment)..

(38) 24. 4.5 Procedures Making use of the aforementioned warm-up sheets, fiveminute pre-listening activities were completed. Field (1998) insists that the length of this activity should be as little as five. minutes, and it was only three minutes in the experiment of Berne (1995). It seems unrealistic to assign 15 to 20 minutes of pre-listening activity for about one minute of listening practice.. The question preview activity (Q Prev) allowed the subjects. to study the listening points, equivalent to the questions of a. post-listening comprehension test, and to guess the answers. Immediately before listening, they were required to reconfirm the listening points. The visual presentation activity (Visual) allowed the students to see the illustration that indicated the environment of the listening text, and to predict the contents of. the text. In the vocabulary activity Noc), the subjects read aloud the unknown words and idioms after the teacher, and they. were required to memorize the meaning of each word. In the sound modification activity (SM), the students struggled with the. partial dictation task including sound changes. Then the dictation was reinforced with a pronunciation drill after the tape. model. The control group (Cont) participated in a crossword puzzle as a fi11er activity, which was irrelevant to the listening. text both in contents and in vocabulary, and which did not involve listening work.. After completing the assigned pre-listening activities and.

(39) 25 turning over their warm-up sheets, the students listened to the. Material 1 (announcements on board the plane) once. Immediately afterwards, they were required to complete the. aforementioned post-listening comprehension test. The questions were not delivered until they had finished listening, thus preventing the subjects from seeing the questions prior to. listening, which is consequently equivalent to the question prevlew actlvlty.. The same procedure was repeated as regards Material 2 (interview), after a five-minute recess. At the end of the. experiment, the previously mentioned questionnaire was delivered. All the distributions used in the experiment, such as. test papers and warm-up sheets, were collected for the administration of follow-up tests. The right answers to the comprehension tests were not provided. These procedures were common to all five groups. The only difference among them was that of the treatment of the pre-listening activities.. One month later, follow-up tests were conducted to investigate whether the pre-listening activity had Ied to progress. in listening proficiency. At this time, no pre-listening activity. was provided. The subjects again listened to the materials of one month before, and tackled the identical comprehension tests.. Figure 4 represents the experimental design in the form of a simple diagram..

(40) 26. ExperimentalGroup. Control. Group. QPrev. Visual. Voc. Predictthe. Mono-. Prelistening Activity. Cross-. word puzzle. listening. questions. text,. ofcomprehension. making. test. logue. Day. Studythe. Test. Post-listeningComprehensionTest1. Prelistening Activity. later. Figure 4.. word puzzle. of. comprehension test. Predictthe Iistening text,. making use ofthe. Studythe. Material2(Interview). Test. Post-listeningComprehensionTest2. Partial dictation of. unknown wordsand sound idioms. visuals. Listening. Questionnaire. 30 days. Cross-. questions. modifications. Material1(Announcementsontheairplane). Studythe. Dialogue. idioms. Listening. Ex-. Partial dictation of. unknown wordsand sound. visuals. of .pen-ment. use ofthe. Studythe. SM. onpost-listeningtestsandpre-listeningactivity. Mono- Listening. Material1(Announcementsontheairplane). logue. Test. Post-listeningComprehensionTest1. Dialogue. Listening. Material2(Interview). Test. Post-listeningComprehensionTest2. Diagram of Experimental Design. 4.6 Results The hypotheses tested were that subjects would attain different comprehension scores by different pre-listening formats.. The comprehension measures were of four types: (1) the combined scores of post-listening comprehension tests 1 and 2; (2) the separate scores of two post-listening tests respectively; (3). modifications.

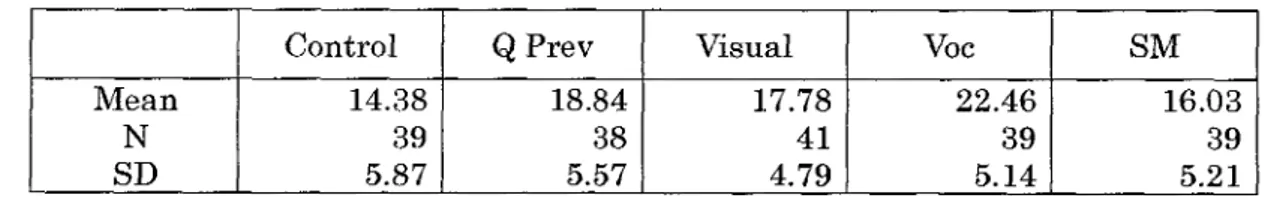

(41) 27 the combined scores of the post-listening tests classified by their. listening proficiency level; (4) the scores of follow-up tests. A. one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted, with the alpha for the F set at .05, to analyze the statistical difference of. the mean scores among the groups. When appropriate, a subsequent post hoc comparison test (LSD) was applied.. 4.6.1 Combined Scores on Post-listening Comprehension Tests Table 2 indicates the mean scores and standard deviations of combined scores in two sorts of post-listening comprehension tests. All of the four experimental groups outscored the control. greup in listening comprehension performance. Table 2. Data of Combined Scores on Post-listening Tests Control. Mean NSD. 14.38 39 5.87. QPrev. Voc. Visual. 18.84. 17.78. 38. 41. 5.57. 4.79. SM. 22.46 39 5e14. 16.03 39 5.21. ANOVA indicated the significant difference statistically,. F(4,191)=12.929, p<.OOI (See Appendix 8, Table 1), on the. average scores among the groups. An LSD test revealed significant differences between the control condition and three. pre-listening forms: question preview (Q Prev); visual presentation Nisual) and vocabulary pre-teaching (Voc), although there was no significance between the control and. soundmodification(SM). Amongthethreeexperimentalgroups in which the significaBt effects of pre-listening treatments were.

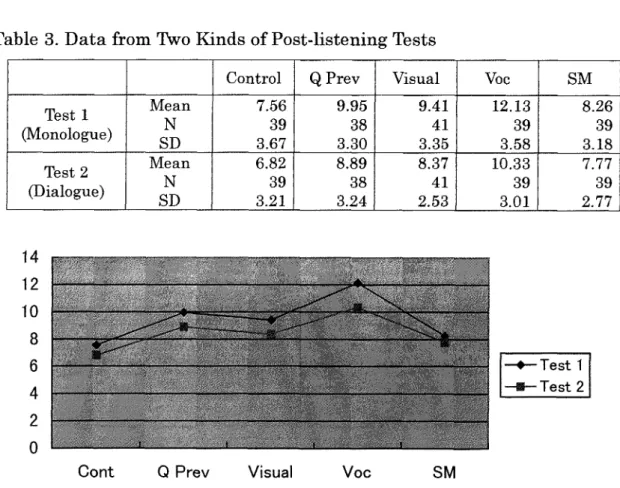

(42) 28 verified, Vec significantly outperformed Q Prev and Visual (see Appendix 8, Table 2 for details).. 4.6.2 Respective Scores on Post-listening Comprehension Tests. Let us look at the subjects' listening comprehension performance separately in two serts ofpost-listening tests. The listening text of comprehension test 1 was a monologue, and that. of comprehension test 2 was a dialogue. The data of each test are presented in Table 3, and Figure 5 graphically illustrates the. mean scores. Each pre-Iistening activity seems te enhance listening comprehension to the same degree, regardless of the text type. Table 3. Data from Two Kinds of Post-listening Tests Control. Test1 (Monologue). Test2 (Dialogue). Mean NSD. Mean NSD. QPrev. Visual. SM. Voc. 7.56. 9.95. 9.41. 39. 38. 41. 39. 39. 3.67 6.82. 3.30 8.89. 3.35 8.37. 3.58 10.33. 3.18 7.77. 39. 38 3.24. 41 2.53. 39. 3.21. 3.01. 39 2.77. 12.13. 14 12 10 8 6. +Test 1. 4. -ae- Test 2. 2. o. Cont QPrev Visual Voc Figure 5. Mean Scores on Post-listening Tests. SM. 8.26.

(43) 29 In order to determine whether or not the efficacy of pre-. listening activities vary according to the text type (i.e.,. monologue and dialogue), the same procedures were applied:. ANOVA and post hoc LSD test. In comprehension test 1 (monologue), a significant difference was found in subjects'. comprehension performance, F (4,191) = 10.346, p<.OOI (see Appendix 8, Table 1). Further investigation, using LSD testing, revealed significant pre-listening treatment effects between the. control condition and three pre-listening activities: Q Prev,. Visual and Voc. The difference between Cont and SM, however, was not significant enough to be verified statistically. Among the three pre-listening activities whose efficacy was confirmed in. listening comprehension, Voc significantly outscores Q Prev and Visual (see Appendix 8, Table 3 for details).. Identical results of analyses were obtained in comprehension test 2 (dialogue): significant differences exist among the five groups, F(4,191) = 7.653, p<.OOI (see Appendix 8,. Table 1); Q Prev, Visual and Voc significantly outperform the control, although SM does not indicate statistical significance; Voc outscores Q Prev and Visual in statistical significance (for details see Appendix 8, Table 4).. 4.6.3 Combined Scores by Differences in Listening Proficiency. Table 4 shows the mean scores and standard deviations on the combined scores of post-listening comprehension tests 1 and 2, according to the subjects' listening proficiency level. Figure 6.

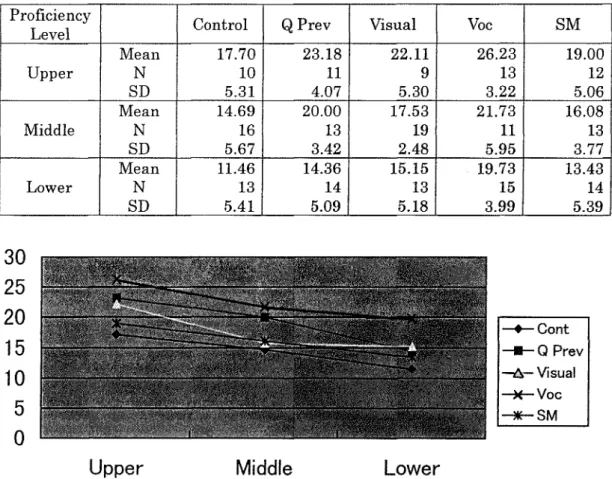

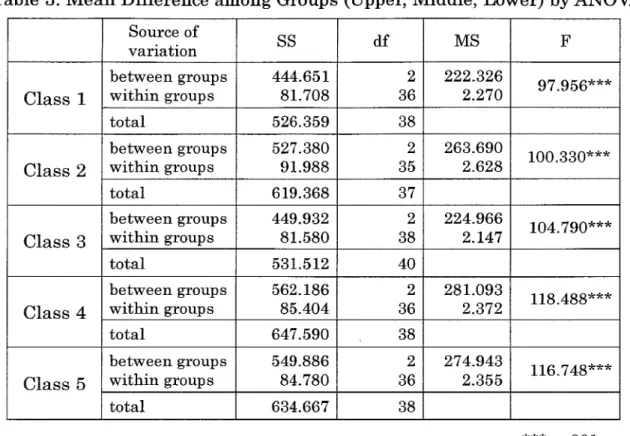

(44) 30 graphically demonstrates the average scores. For all three proficiency levels, the vocabulary group obtained the highest. score followed by the question preview or visual group. The sound raodification group had the lowest score among the four experimental groups. Table 4. Data of Combined Scores by Listening Proficiency on Post-listening Tests Proficiency. Control. Level. Mean Upper. N. SD Mean Middie. N. SD Mean Lower. N. SD. 30 25 20. 17.70 10 5.31 14.69 16 5.67 11.46 13 5.41. QPrev 23.18. 22.ll. 11. 9. 4.07. 5.30 l7.53 19 2.48 15.15 13 5.18. 2o.eo 13 3.42 14.36. 14 5.09. SM. Voc. Visual. 26.23 13 3.22 21.73 11. 5.95 19.73 15 3.99. 19.00 12 5.06 16.08 13 3.77 13.43 14 5.39. + Cont -)e Voc. o. Upper Middle Lower Figure 6. Mean Scores by Listening Proficiency on Post-listening Tests. ANOVA showed significant differences among the five groups at all three levels: Upper level, F(4,50) = 6.414, p<.OOI; Middle level, F(4,67) = 5.691, p<.Ol; Lower level, F(4,64) = 5.358,. p<.Ol (see Appendix 8, Table 5). Subsequent LSD testing.

(45) 31 revealed the following results.. (1) Upper Level Three types of pre-listening activities (Voc, Q Prev and Visual). indicate a significant pre-listening treatment effect in comparison with the control condition, while SM does not reach. significance. Among the three effective activities, Voc significantly outscores Visual (see Appendix 8, Table 6 for details).. (2) Middle Level. In comparison with the control condition, a significant difference was found in two types (Voc and Q Prev), although the other two (Visual and SM) did not indicate significance. It. was also revealed that Voc and Q Prev were in the same rank order, indicating no significant difference between them (for details see Appendix 8, Table 7).. (3) Lower Level. It was Voc only foT which a significant treatment effect was verified compared with the control condition. The other three pre-Iistening activities (Q Prev, Visual and SM) did not reach statistical significance (for details see Appendix 8, Table 8).. 4.6.4 ScoresonFollow-upComprehensionTests In order to examine whether or not pre-listening activities contribute to learners' progress in listening proficiency, follow-up. tests, identical to the post-listening comprehension tests, were.

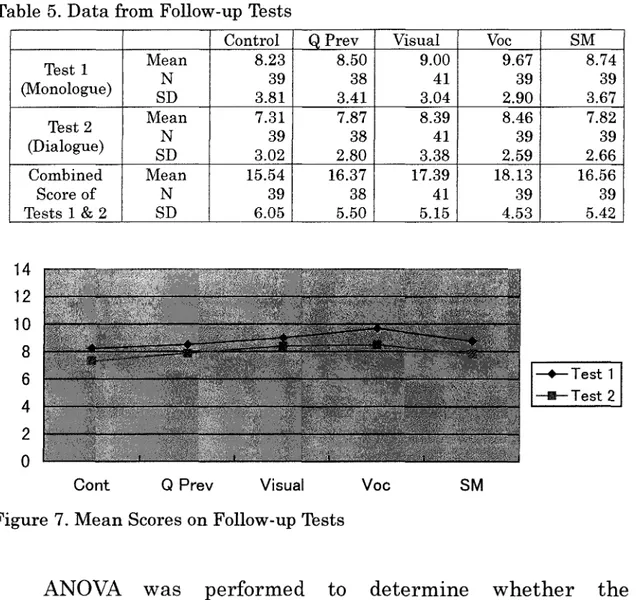

(46) 32 administered 30 days later. Table 5 indicates the mean scores and standard deviations of the follow-up tests, with graphical. illustration of mean scores in Figure 7. Although the experimental groups barely outscored the control condition, the difference in the mean scores is extremely trivial at this time, which is u'. nlike the case with the post-listening tests.. Table 5. Data from Follow-up Tests. Testl (Monologue). Test2 (Dialogue). Combined Scoreof. Tests1&2. Mean NSD. Mean NSD. Mean NSD. Control 8.23 39 3.81 7.31. Prev 8.50 38 3.41 7.87. 39. 38. 3.02 15.54. 2.80 l6.37. 39 6.05. 5.50. 38. Visual 9.00 41 3.04 8.39 41 3.38 17.39 41 5.15. SM. Voe. 8.74. 9.67. 39. 39. 2.90 8.46. 3.67 7.82. 39. 39. 2.59 18.13. 2.66 l6.56. 39. 39. 4.53. 5.42. 14 12. IO 8. +Test 1. 6. ma Test 2. 4 2. o. Cont QPrev Visual Voc SM Figure 7. Mean Scores on Follow-up Tests. ANOVA was performed to determine whether the differences among the five groups were significant or not. No. significance was revealed in any of the three cases: Test 1. (monolegue), F (4,191)=1.026, n.s.; Test 2 (dialogue), F.

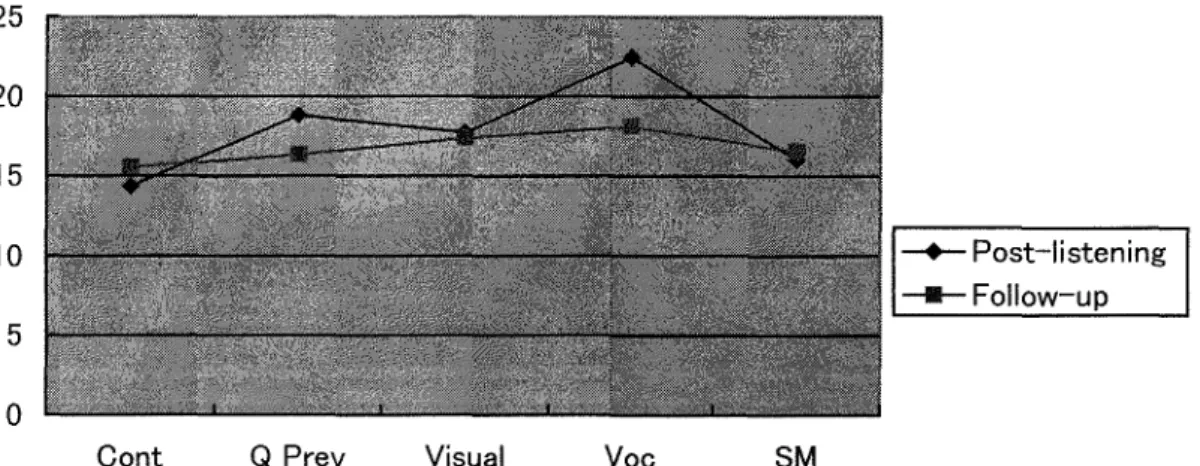

(47) 33. (4,191)=1.033, n.s.; Combined Scere of Tests 1 and 2, F (4,191)=1.349, n.s. (see Appendix 9, Table 1). Additional analysis classified by listening proficiency also exposes no. significant differences among the five groups at all three proficiency levels: Upper level, F (4,50) ex e.693, n.s.; Middle level,. F (4,67) = O.705, n.s.; Lewer level, F (4,64) = 1.304, n.s. (for details see Appendix 9, Tables 2 and 3). ' Table 6 compares the cembined scores in the follow-up tests. with those of the post-listening tests. In Figure 8, the mean scores of both tests are displayed graphically, and they reveal notable decreases in the cases of Voc and Q Prev. Table 6. Comparison of Post-listening and Follow-up Tests Control Post-listening. aests1&2. Mean NSD. combined Follow-up (']]estsl&2. combined). Mean NSD. 14.38. Prev l8.84. 39. 38. 5.87 15.54. 5.57 16.37. 39 6.05. 38 5.50. Voc. Visual 17.78. 41 4.79 17.39 41 5.15. SM. 22.46 39 5.14 l8.13 39 4.53. 25. 20 15. +Post--listening. 10. - FollowMup 5. o. Cont QPrev Vlsual Voc SM Figure 8. Comparison of Mean Scores on Post-listening and Follow-up Tests. 16.03. 39 5.21. 16.56 39 5.42.

(48) 34 Chapter 5 Discussion. Based on the findings from the experimentation as described in the previous chapter, the following discussion attempts to explain the results obtained. Implications for the classroom are also presented in order to arrive at appropriate pre-listening activities for Japanese senior high school students.. 5.1 Facilitative Effects ofPre-listeningActivities on Listening. Comprehension With respect to the first hypothesis, the data partially supported that listening comprehension is facilitated by the pre-. listening activities regardless of the type of activity. The treatment effects of three types of pre-listening activities (Voc, Q. Prev and Visual) were verified, while SM, contrary to our expectation, did not contribute to the extent that significant differences could be observed. The reason why SM did not reach significance is considered to be that the experimental materials,. which were extracted from textbooks for Japanese senior high school students, do not include phonological modifications as. numerously as are found in spontaneous English speech. These results suggest that familiarizing students with phonological modifications, the importance of which is not ignored, should not be so efficient at the pre-listening stage in the case of textbook. materials, and that such an activity should be desirable as.

(49) 35 feedback after listening. The facilitative effect of vocabulary. pre-teaching, which was not significant in Berne (1995), was ascertained. The difference is probably due to the defects in her experimental design as described in 3.1. It is meaningful that the treatment effects of three types of. pre-listening activities (vocabulary pre-teaching, visual presentation, question preview) were substantiated. Taglieber et al. (1988) recommends three kinds of pre-reading activities (pictorial context, vocabulary preteaching and prequestioning) as. effective and practical techniques for reading comprehension,. which is considered applicable to listening comprehension. In lesson planning, we can select one of the three pre-listening techniques, depending on student needs and the characteristics. of the text, or we can combine all three in the same class. Familiarizing the students with sound modification prior to. listening, which received no confirmation in the present experimentation, might be an effective method if it is presented. with the meaning of the chunk constituent that is about to be heard.. 5.2 VocabularyPre-teachingvs.SchemaActivation In terms of the second hypothesis, the data supported that vocabulary pre-teaching is more facilitative for Japanese senior. high school students than schema activation by visual. presentation. Vocabulary pre-teaching Noc) produced significantly greater degrees of comprehension enhancement.

(50) 36 than did schemata activation by presenting illustrations (Visual),. both in monologue and dialogue materials and in all the levels of. subjects' listening proficiency. This finding is consistent with Shizuka (1994) concerning the effects of pre-reading activities,. contrary to the commonly held generalization that vocabulary pre-teaching is not as effective as inducing relevant schemata.. It is true that the comprehension advantage derives from. the experimental design, in which sufficient numbers of unknown words and expressions were listed together, and in. which the sounds and meanings of the vocabulary were adequately connected. If the treatment were reduced, the outcome would be different, as the precedent research indicated. and which was discussed in Chapter 3. The type of vocabulary instruction in this experiment, however, is frequently observed and not special in the least to our situation.. Two other reasons of great importance should not be overlooked, though. First, the vocabulary level ofthe textbooks. for Japanese senior high school students is considerably high.. Hatori (1979) and Takanashi (1995) argue that the ability to infer unknown words, in the case of reading comprehension, is almost impossible when they exceed 50/o of total word count. In. listening comprehension, which requires on-line information processing, inferring unknown words is still more burdensome. than in reading comprehension. The percentage of unknown words, which the dictionary prescribes as those not yet learned in junior high school, was 10.80/o of all the words in Material 1.

(51) 37 and 7.60/o of all the words in Material 2. That is to say, the. materials used in the experimentation include so many new words for the students that they cannot infer the meanings of the. words from context, and consequently they fail to understand a passage or a conversation.. A second reason is concerned with the contents of the materials. In the precedent studies stressing the importance of. background knowledge, arduous materials were intentionally employed that were ambiguous or hardly interpretable without. cultural or religious background (Anderson et al. 1977, Steffensen 1981, Markham and Latham 1987, Long 1990). In the textbooks for high school students, on the other hand, such peculiar materials are rarely found.. Many reading researchers argue that L2 reading comprehension is influenced by language problems rather than reading problems, especially when students are not yet reading. at the prescribed proficiency (Clarke 1980, Alderson 1984,. Yamashita 1993). This assertion is considered valid for listening comprehension as well. It should be deduced that familiarizing the students with unknown vocabulary prior to listening can be a highly efficient technique for increasing Iistening comprehension among Japanese high school students, especially when textbook materials are used.. 5.3 TextIlypeandListeningProficiency The third hypothesis, which proposed that effective types of. pre-listening activities are common between monologue and.

(52) 38 dialogue materials, was supported since identical results were obtained in both cases. In both cases, the efficacy of three kinds of pre-listening activities (Voc, Q Prev and Visual) was verified,. and the results show that vocabulary pre-teaching Noc) is the. most facilitative for comprehension. Each type of activity. results in the same degree of comprehension enhancement, whether the material used is a monologue or a dialogue. The reason for this is thought to be that the identical nonreciprocal task, in which students listen to oral texts in order to. obtain information, was imposed on the subjects in both cases,. regardless of the number of speakers (i.e., monologue or dialogue). In classroom application, teachers are encouraged to use the three types of activities as previously stated, whether the. material is a monologue or a dialogue.. With regard to the fourth hypothesis, the results of our experiment supported that the effectiveness of each type of pre-. listening activity differed according to the L2 listening proficiency of the subjects. At the upper proficiency level, the. efficacy of three types (Voc, Q Prev and Visual) was demonstrated, at the middle level two types (Voc and Q Prev) and. at the lower level only one (Voc). These findings indicate that vocabulary pre-teaching is an efficient technique for facilitating comprehension in spite of learners' listening proficiency, and that. visual presentation and question preview become less effective aids as the listening proficiency lowers. The reason why Visual was effective only for the upper-level students is thought to be. that the learners with middle and lower proficiency failed to.

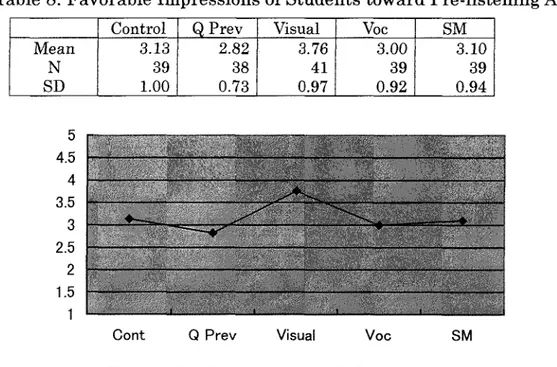

(53) 39 induce relevant schemata, or the schemata they activated were. inappropriate. The lack of treatment effect of Q Prev among lower-level learners is thought to result from those students' insufficient knowledge of the language, especially in vocabulary.. Limitations to their vocabulary impeded their comprehension. The learners with high listening comprehension proficiency seem to make the best use of all types of pre-Iistening activities. for their comprehension, while low-proficiency learners seem to. avail themselves only of direct and specific information. The present study agrees with Takefuta (1997) on this point, arguing. that the information for top-down processing is ambiguous in many cases, so that learners, especially beginners, frequently fail. to take advantage of it. For the purpose of increasing the comprehension of low-listening-proficiency learners, it is necessary to provide them with vocabulary items, or with visuals that illustrate to some extent what they are Iistening for.. 5.4 ProblemsinVocabularyPre-teaching Although the facilitative effect of vocabulary pre-teaching. was more powerful than any other pre-Iistening form in this. study, some inexpediences were discovered through the responses to the questionnaire that the students completed after. the experiment. Table 7 indicates the average scores the students gave for. the question of whether or not the pre-listening activity heightened their incentive to listen. The Iarger numerical value. represents that their motivation was more enhanced, since they.

図

関連したドキュメント

Keywords: homology representation, permutation module, Andre permutations, simsun permutation, tangent and Genocchi

As we shall see, by using the Bailey chain concept the search for appropriate Bailey pairs and the problem of proving or discovering such identities are far easier to handle and

An easy-to-use procedure is presented for improving the ε-constraint method for computing the efficient frontier of the portfolio selection problem endowed with additional cardinality

If condition (2) holds then no line intersects all the segments AB, BC, DE, EA (if such line exists then it also intersects the segment CD by condition (2) which is impossible due

Then it follows immediately from a suitable version of “Hensel’s Lemma” [cf., e.g., the argument of [4], Lemma 2.1] that S may be obtained, as the notation suggests, as the m A

Applications of msets in Logic Programming languages is found to over- come “computational inefficiency” inherent in otherwise situation, especially in solving a sweep of

Classical definitions of locally complete intersection (l.c.i.) homomor- phisms of commutative rings are limited to maps that are essentially of finite type, or flat.. The

Shi, “The essential norm of a composition operator on the Bloch space in polydiscs,” Chinese Journal of Contemporary Mathematics, vol. Chen, “Weighted composition operators from Fp,