The

Effect

of

Presentation

as

a

Function

ofModality

on

Text

Memory

Difllculty

Level')

MachikoSANNOMIYA

OsaleaUhaiversity

The

effect ofpresentation

modality ontext

memory wasinvestigated

by

manipulatingthe

dirnculty

level

oftext

content.An

easy and adiracult

texts,

which were almost equalin

length,

werepresented

in

one ofthree

modalities(auditory,

visual, and audiovisual) and remembered,Free

recall was used and recallprotocols

were scoredfor

20

idea

units.The

results showed a modality effect, thatis,

the superiority of auditory over visual andaudio-visual

presentation

in

recallperformance.

Auditory

superiority,however,

wasfound

for

the

dithcult

text

only, and was not restrictedto

the

recencypart.

These

results cannotbe

ex-plained

by

the

precategorical

storehypothesis

whichis

a widespreadinterpretation

of themodality effect on word-list memory.

Instead,

onepossibility

was suggestedin

terms ef capacity shortage owing to the translation ofprinted

letters

into

an auditoryforrn

whichimpaires

theprocessing

of thedithcult

text.Key

words: the modality effect,presentation

medality, text memory,difficulty

Ievel,

text

content, capacity shortage,

translation,

The

effect ofpresentation

modality on memoryfor

semantically unrelated verbal materialshas

been

reviewed

by

Penny

(1975).

The

modality effect, which was obtained withlists

of words, nonsense-syllables,letters,

anddigits,

denotes

the

superiority of auditoryover

visualpresentation

asmeasured

by

recallor

recognition

methods.The

maincharacter-istics

of

the

modality effect werethe

following

:(1)

The

effect

is

restricted

to

the

recency

part

of a

list.

(2)

Adding

auditory

presentation

or

subjects' vocalization

to

visual

presentation

resultsin

aperformance

equalto

that

obtained with auditorypresentation.

(3)

The

effect

is

stronger when

presentation

rateis

high.

Since

text

processing

includes

processing

of

word$, we can

expect

some

influence

ofpre-sentaion modality on

text

memoryas

well.It

is

deubtful,

however,

whetherthe

effectis

the

sameas

that

for

word-list memory,because

1)

This

researchforms

part

of a master thesisof

the

auther which was subrnittedto

Osaka

University.

The

authoris

gratefulto

Professor

Ono

for

his

helpful

comments on an earlierversien of

this

paper.

additional

factors

are mostprobably

involved

intextmemory,

Kintsch

et

al.

(1975)

comparedtext

comprehension and memory afterlistening

and reading.They

reportedthe

absence of modalitydifference.

But

these

results cannot・be

generalized

because

the

texts

used wererelatively easy, and

the

authorsthemselves

noted

that

the

equivalent

performance

underboth

modalities might nothold

for

moredif-ficult

texts.

Moreover,

they

permitted

subjectsof

the

reading

group

to

return

to

earlier

parts

of

the

text

and

to

make

arbitrary

time

allot-ment

to

different

parts

ofthe

text

withina

limited

overalltime.

Subjects

ofthe

listening

group

did

not sharethese

advantages.They

could

neither

return

to

earlier

parts

norstop

the

presentation

at

some

particular

points

in

order

to

reflect upondithcult

description.

It

is

true

that

a

perfect

equivalence ofauditory

and

visualpresentation

cannotbe

obtained,but

it

is

pessible,

atleast,

to

diminish

the

un-equivalence

to

alarge

extent,The

above considerations suggestthe

needfor

aninvestigation

of

the

modality effect onmemory

ior

dithcult

texts

under moreThe Japanese Psychonomic Society

The JapanesePsychonomic Society

86

The

Japanese

Journal

ofexperiment,

the

modality effect ontext

me-mory was examinedfor

two

levels

ofdiMculty

in

comprehension.Other

factors

which wereknown

to

infiuence

text

memory wereheld

constant,

that

is,

number of words, number of noun concepts,and

judged

interest

level.

Audiovisual

presentation

was examinedin

ad-dition

to

auditory and visualpresentation

in

order

to

find

out

whetherthe

superiority

of

audiovisual over visual

presentation

holds

for

text

memory as well.

Method

Subjects

Sixty

undergraduate students atOsaka

University

andKonan

University

served assubjects.

They

were randomely assignedto

six

conditions.The

ratiobetween

male andfemale

was made equalin

all conditions.Design

A

3x2

between-subject

design

was

used.There

werethree

types

ofpresentation

ino-dality

(auditory,

visual, and audiovisual).And

there

were

two

types

of

diMculty

level

ef

comprehension

(easy

anddithcult),

Materials

First

of

alt,

three

easyand

three

clithcult

texts

wereselected

by

the

author and ratedby

ten

judges

onfive-point

scalesfor

dificulty

of

comprehensionand

interest

level,

The

judges

were

post-graduates

and

undergraduatesof

psychology

at

Osaka

University.

Of

the

above

six

texts,

two

texts

were

selected

for

the

experirnent.

They

were

rated

as

of

ap-proximately

equalinterest

(Mean

value andSD

were1.9;

.70

for

the

easytext

and

2,O;

.63

fer

the

dithcult

text;

t(18)=:.45)

but

different

dificulty

(Mean

value andSD

were2.3;

.46for

the

easy

text

and

4.5;

.50for

the

dithculttext:

t(18)=13.74,

P<.Ol).

Both

texts,

divided

into

idea

units, are shownin

the

appendix,

Each

text

consisted

of

110

Japanese

words(Bunsetsu).

The

number ofnoun concepts was

31

in

the

easytext

and30

in

the

dithcult

text.

Phrocedure

,

Subjects

wereinstructed

to

try

to

compre-hend

and

remember

the

presented

text

soas

to

be

able

to

recall

it

after

three

times

of

presentation

andto

reproduceit

usingthe

original expressions

if

possible.

For

auditoryPsychonomic

Science

Vol.

1,

No.

2

presentation

the

text

was recordedby

the

taperecorder

withfemale

voice.Presentation

rate was about

5

letters/sec

in

terms

ofKana

letters2).

Care

wastaken

to

readthe

material monotonously witheut strongintonations

andpauses

which could serve as rememberingcues.

In

visualpresentation,

subjects werepermitted

to

readthe

material,printed

on

a

sheet

of

paper,

at

their

habitual

pace,

satis-fying

the

following

two

restrictions

:(1)

They

should

not

return

to

earlier

parts

of

the

text.

(2)

They

should

readat

a constantpace

with-out

stops

and

pauses

for

thinking.

These

restrictions were

imposed

in

orderto

equalizethe

number ofpresentations

in

the

visual and auditory conditions.In

audiovisualpresenta-tion,

subjectslistened

to

the

taped

material

in

the

same way asin

auditorypresentation,

and readthe

correspondingJapanese

characters simultaneouslyfrom

a

sheetof

paper,

which wasthe

sameas

that

usedfor

visualpresenta-tion.

Asynchronous

reading wasnotpermitted.0vert

vocalizationwas

not

permitted

for

all

conditions.

The

presentation

ef

atext

was repeatedthree

times,

because

in

apreliminary

experimentonce

or

twice

of

presentation

was reportedto

be

quite

insudicient

for

compre-hension

ofthe

dithcttlt

text.

Immediate

recall was required and recallprotocols

were written on ablank

sheet ofpaper

without

time

limit.

Results

In

the

case of visualpresentation

whieh was self-paced,the

average

presentation

rate(read-ing

rate) was5,20

letters/sec

in

the

easytext,

and

was5,23

lettersfsec

in

the

dificult

text.

They

hardly

differed

from

that

of

auditoryand audiovisual

presentation

rate,5

letterslsec

(t(9)=

.81;

t(9)=.92).

Recall

protocols

were

scoredfor

the

presence

ofthe

20

idea

unitsof

the

respective

texts.

Scoring

was

based

on

the

discussion

of

two

2)

Japanese

textsinclude

not onlyKana

letters

(i.e.

the

phonograrn

which correspondsto

onesyllable)

but

alsoChinese

letters

(i.e.

the

gram

whichdoes

nothave

fixed

relationshipto

syllables).When

calculatingpresentation

rate,

Chinese

letters

were convertedinto

Kana

letters.

Therefore

5

lettersfsec

is

eqttivalent

Table

1.

Mean

number andSD

of recalledidea

unitsPresentationModality

DithcultyLevel

Auditory

Visual

Audiovisual

M

SD

mttttt

M

SD

M

SD

Easy

13,6(68,O%)

3.07

..-

Dithc-l.lt..r-

13,O(65,O%)

2157

judges

including

the

author,They

scored onepoint

if

the

gist

of anidea

unit was reproduced.Table

1

showsthe

average number ofidea

units correctly recalled

in

eachgroup.

A

3

×2

(modality

by

dithculty)

analysis of varianceyielded

significant main effectsfor

modality(li<2,

54)==3.40,P<.05)

and

didiculty

(F(1,

54)=24,49,P<.Ol),

Above

all,the

interaction

was significant(F(2,

54)

=4.28,

P<.05).

Multiple

comparison wasperformed

for

the

number of correct recallafter

three

medalities

by

usingSheffe's

method,There

was

no

significant

difference

among

them

in

the

easy

text,

whereasit

wasgreater

afterauditory

than

visual and audiovisualpresenta-tion

in

the

diMcult

text

(P<.Ol),

And

com-paring

two

diMculty

levels,

there

was nosigniticant

difference

in

recall afterauditory

presentation,

whereasthe

easytext

wasbetter

recalled

than

the

dithcult

one after visual and10

:eR6

:5'6

4:3l,

1

o

Fig.

H aL'ditorv N visual80

14.1(70.5%)

2.20

42

9.1(45,5%)

1.70

audiovisual

presentation

(p<.OI).

In

previous

re$earches,

modality

differences

have

been

reportedto

be

specificto

the

re-cencyitems

in

the

memoryfor

semantically unrelated materials(Penny,

1975).

Therefore

it

seemsto

be

meaningfulto

examinethe

re-lationship

between

the

modality effect andserial

positions

alsoin

the

caseof

text

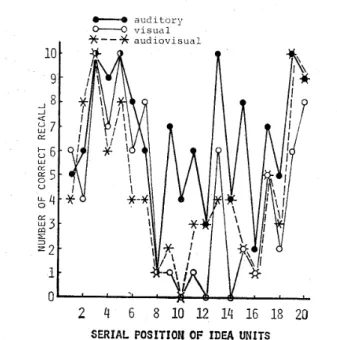

memory.Fig.

1

shows recall ofthe

dificult

text

for

each

presentation

modality as afunction

ofserial

position

ofidea

units.Obviously

audi-tory

superiorityis

not

specific

to

the

recencypositions.

Fig.

2

wasintroduced

to

makeclearly

the

relationbetween

modality differ-ences and serialpositions.

It

shows

the

recallperfermance

for

each modalityin

the

primacy,

middle,

and recencypart

ofthe

text

(Each

part

comprise$

6,

8,

and6

idea

units, respectively).A

3

×3

(modality

by

part)

analysis of varianceyielded

significant main effectsof

modality

(xZ(2)

=25.

48,

P<

.Ol)

and

part

(x2(2)

==67

.62,

P<.Ol),

but

no significantinteraction

(xZ(4)=:

13.8.7

(68.5

(42,5%)

3.

5%)

2s

2

4

5

8

ZO

l2

14

16

18

20

SERIAL POSITION OF rDEA UNrTS

1,

Correct

recallin

each modality as afunction

of serialposition

ofidea

units(for

the

dithcult

text).

Fig.

10

9y,8g7

k,s

EsS4m]EM.22

1

o

PRIMACY MIDDLE RECENCY SERIAL PART- OF ]DEA UNITS

2,

Correct

recallin

each modality as afunction

of serialpart

efidea

units(for

The Japanese Psychonomic Society

The JapanesePsychonomic Society

88

The

Japanese

Journal

ofPsychonomicScienceVol.

1,

No.

2

4.09).

Nevertheless

there

seemsto

be

sometrend

of

interaction

between

modality andpart.

As

can

be

seenin

Fig.

2,

it

is

true

that

there

is

no significant main effect of modality

in

the

primacy

part

(F(2,'27)==1.39),

whilethere

exists

the

main effectboth

in

the-middle

(F(2,

27)=11.19,P<.01)

andin

the

recencypart

(F(2,

27)==8.62,P<.Ol).

But

we

cansay, at

least,

that

auditory superiorityis

not restrictedto

the

recencypart

only.Discussion

The

present

experiment showedthe

existenceof a modality effect on

text

memory.It

is

different

from

the

modalityeffect

on

semanti-calry unrelated verbal materialsin

the

follow-ing

three

points:

(1)

A

modalityeffect

wasfound

for

the

ma-terial

judged

didicult

to

comprehendbut

notfor

the

materialjudged

to

be

easy, altheughboth

texts

were almostequal

with

respectto

number of words and noun concepts as well

as

judgecl

interest

level.

(2)

Auditory

presentation

was superior notonly

to

visualbut

alsoto

aucliovisu41presenta-tiop,

while audievisualpre$entation

was not$ignificantly superior

to

visualpresentation,

(3)

Auditory

superiority was not specificto

the

recencypart

of

the

material.For

the

modality

effect

on

memoryfor

letter-,

digit-,

nonsen$e

syllable- andworcl-lists,

two

main

interpretations

have

been

put

forward

:

(1)

The

"PrecategoricalStore

Hypothesis"

postulates

separate

precategorical

stores

for

auditory stimuli

(precategorical

acousticstore

:PAS)

and

for

visual stimuli(precategorical

visualstore:

PVS).

The

information

stored

in

PAS

facilitates

recallfrom

short-termme-mory

and

produces

stronger recency effect.The

information

in

PVS

decays

muchfaster

than

that

in

PAS

andtherefore

cannotbe

made use

of

at

the

time

of recall(Crowder

&

Morton,

1969).

(2)

The

"TranslationHypothesis"

postulates

the

translation

of

visualinput

into

an auditoryform

whenverbal

materials

are

visually

pre-sented,

This

additionalprocessing

requires cognitive capacity andtherefore

less

cognitive capacityis

availablefor

further

processing

in

the

case of visualpresentation

as compared with auditorypresentation

(Laughery

&

Pinkus,

1966).The

translation

hypothesis

cannot

explain

why

the

modality effectis

restrictedto

the

recencypart

of

a

list.

Therefore

the

precategorical

store

hypothesis

has

been

morebroadly

accept-ed.

The

latter

hypothesis

explains

also

the

superiority

oi

audiovisual

over

visual

presenta-tion

based

onthe

availability of auditoryin-formation

in

PAS.

However,

the

properties

ofthe

modalityeffect en

text

memory are at variance withthe

predictions

from

the

precategorical

store

hypothesis.

Neither

the

restrictionof

the

effect

to

the

recency

part

of

the

learned

ma-terial

nor

was

the

superiority

of

audiovisualover

visual

presentation

was

observed.

Since

the

modalitydifferences

were

specific

to

the

text

dificult

to

comprehend,it

seemsthat

the

search

for

an explanation mustbe

directed

towards

the

process

of

comprehension ratherthan

towards

precategorical

proce$s.

Consider-ing

that

the

translation

hypothesis

takes

into

account

the'

further

precessing

than

sensory memory,this

hypothesis

appearsto

be

morepromising.

It

suggests

the

following

inter-pretation:

The

dithcult

text

requires rnorecognitive capacity

for

its

comprehensionthan

the

easy one.Therefore,

in

the

case of visualpresentation,

the

processing

necessaryfer

cornprehension

is

moreliable

to

be

impaired

by

the

shortage of capacity whichis

causedby

the

translation

of visua!input

into

anauditory

form.

Probably

the

presentation

time

was not suficientfor

comprehendingthe

dithcult

text,

whileit

was suthcientfor

com-prehending

the

easy

text.

In

other

words,

the

presentation

rate was substantiallyhigh

fer

the

dithcult

text

but

it

was substantiallylow

for

the

easyone,

although

real

presenta-tion

rate was constantfor

both

texts.

Ori

the

basis

ofthis

interpretation,

our result seemsto

be

quite

congruous withthe

fact

that

visualinferiority

is

augmented

when

presentation

rate

is

high

(Murdoek

&

Walker,

1969).

On

the

otherhand,

the

inferiority

of

audio-visual

presentation

in'the

ditheult

text

eeems

to

be

a

rnore complicatedphenomenon.

Trans-lation

process

is

not necessaryin

this

modality

Therefore,

if

we assumethat

printed

letters

were not

translated

into

an auditoryform

in

the

audiovisual condition,the

translation

hypo-thesis

cannotexplain

this

result.However,

wasthe

translation

really notperformed

in

the

audiovisual condition?We

cannot assert

that

our

subjectsin

the

audio-visualgroup

did

nottranslate

the

prints

be-causeit

was not necessary.As

a matter offact,

we cannothelp

but

read(translate

prints

into

sounds atthe

inner

level,

at

least)

even when we need notdo

soin

atask

to

namethe

color of words(Stroop,

1935).

And

if

the

translation

is

inevitable

process,

it

is

possible

to

explainthe

inferiority

of audiovisualpre-sentation

in

the

dithcult

text

in

the

same way asthat

for

the

visualinferiority,

that

is,

in

terms

of

capacity

shortage,

which

is

based

on

the

translation

hypothesis.

But

it

is

queer

that

audiovisualinferiority

is

peculiar

to

text

processing.

The

present

research cannotpro-vide

any

explanation onthis

point.

It

only suggeststhat

some specificprocess

oftext

comprehensionis

sensitiveto

audiovisual dis-advantage.It

mightbe

syntacticprocessing,

that

is,

the

process

ofintegration.

Finally,

,we

should notedithculty

level

oftexts.

In

this

experiment,

dithculty

leVel

of

texts,

which appearedto

be

oneof

the

deter-minants of

the

modality effect ontext

memory, was measuredby

judgement

on5-point

Scales.

So

the

level

ofdithculty

depended

onthe

readers'

impression

oftexts.

In

orderto

investigate

the

modality effect oncomprehen-sion

process,

it

is

necessary

to

specify

the

factors

ofdiMculty

Ievel

oftexts.

We

canassume some

different

factors

ofdithculty

in

the

dithcult

text.

That

is,

for

instance,

un-familiarity

oflexicon,

complexity of syntax,abstractness of content, vagueness

of

expres-sion, and so on.

They

maydifferently

infiuence

the

modality effect.We

have

to

examinethose

factors

separately

in

the

next step.

References

Crowder,

R,G.

&

Morton,

J.

1969

Precategorical

acoustic storage

(PAS).

Percertion

&

phisics,

5,

365-373.

Kintsch,

W.

Kozminsky,

E.,

Streby,

W.

J.,

MeKoon,

G.

&

Keenan,

J.M.

1975

Comprehension

andrecall of text as a

iunction

of content variables.

Iburnal

of

Vlarbal

Learning

andVlarbal

Behavior,

14,

196-214.

Laughery,

K.R.

&

Pinkus,

A.L.

1966

Short-term

memory:

Effects

of acoustic siniilarity,sentation rate, and

presentation

mode.chonomic

Science,

6,

285-・286.

Murdock,

B.B,

&

Walker.

K,D,

'1969

Modality

effects

in

free

recall.Iburnal

of

Vlarbal

itrg

andVerbal

Beha2,ior,

8,

665-676.

Penny,

C.G.

1975

Modality

effectsin

short-terrnverbal memory,

PsycholQgt'cal

Bulletin,

82,

84.Stroop,

J.

R.

1935

Studies

ofinterference

in

serialverbal reactions.

fournal

of

ExPerimental

chology,

18,

643-661.

APPENDIX(LEARNING

MATERIALS

:EASY

AND

DIFFICULT

TEXT

(B))

TEXT

(A),

(A)

A

dietetic

seminarfor

mothers1)

Vitamin

A

is

measuredin

International

Unit

(I.U.).

2)

That

is

because

Vitamin

A

is

obtainedf'rom

carotenes also.3)

The

I.U.-measure

is

derived

from

the

effect

ofVitamin

A

onthe

growth

of a

rat.

5)

1

I.U.

ofVitamin

A

increases

the

weight

of

a

ratby

3

gram

per

day.

4)

whenwe

feed

a

young

one

destitute

of

Vitamin

A.

6)

1

I.U.

correspondsto

O.3

rnicrogram of

Vitamin

A.

7)

P-carotene

consists oftwo

molecules of

Vitamin

A.

8)

whileother

carotinoids consistof

one

melecule of

Vitamin

A.

9)

Plants

contain alot

ofP-carotene.

10)

1

I.U.

correspondsto

O.6

microgramof

carotenes.

11)

Since

the

absorption rate of carotenesis

low,

12)

the

actual eraciency ofVitamin

A

in

The Japanese Psychonomic Society The Japanese

90

13)

14)15)16)17)18)

20)19)

1)

3)

2)

5)

4)

6)

7)

8)

9)

10)

12)

Psychonomic SocietyThe

Japanese

Journal

offood-element

table.

So

the

amount

of

carotenes

is

represented

as

Vitamin

A

effect

afterdividing

its

amount

by

3.

The

carotene valueof

spinach

is

8000

I.U.

and

its

Vitamin

A

effectis

2600

I.U,.

The

carotene value of carrotsis

4000

I.U,

and

its

Vitamin

A

effectis

1300

I,U..

As

processed

cheese containsVitamin

A

and carotenes,

its

Vitamin

A

effectis

500

I.U.

by

adding

410

I.U.

and9e

I,U..

(B)

Leaming

There

aretwo

methods oftesting

human

memory.

・

One

is

the

recognition methodwhich

tests

whether apresented

item

is

familiar

to

a

subject.

Another

is

the

recall methodwhich requires a subject

himself

to

re-produce

whathe

remembersby

writingor speaking.

So

far

the

term

recallhas

been

usedin

both

meanings,and

it

is

actuallydithcult

to

regardboth

as

fundamentally

different,

Although

it

is

not necessarily anexternal

stimulus which

is

recognized,a

recognitionprocess

mustbe

involved

in

both

cases.

Our

brain

reproducesin

some wayin-ternal

stimuli,thus

giving

riseto

recallPsychonornic

Science

Vol.

1,

No.

2

11)

due

to

the

interaction

between

reproducedinternal

stimuli

and

the

appropriate

engram.

13)

The

mechanism

of

recall

is

still

unclear

at

present.

15)

Recall

of a stimulusis

possible

within aperiod

of afew

minutes afterits

rence,

14)

whenthe

engramis

sensitiveto

ance

and

damage,

16)

If

the

engram

is

wellestablished

17)

recall canfunction

within afew

seconds.18)

Recall

may occurlater

without consciouseffort

even

after

a

momentaryrecall

ure.

20)

It

is

an example ofthe

above19)

that

we suddenlyremember

someone'sname while

thinking

about somethingelse a while after we

have

the

name onthe

tip

of ourtongue

but

are not ableto

produce

it.

Note

1)

Japanese

words(Bunset$u)

do

notalways correspond

to

English

words,2)

Japanese

nouns

are

sometime$

embedded

in

the

words which correspondto

Engli$h

ad-jectives.

3)

The

arrangement

of

clauses

in

a

Japanese

sentence sometimes

differ

from

that

in

the

corresponding

English

sentence,

The

serial

numbers