Teaching Traditional Japanese Culture in

English: Cultural Distance and Cognitive Load in EMI and CLIL Contexts

journal or

publication title

Journal of Research and Pedagogy of Otemae university Institute of International

Education

volume 6

page range 74‑86

year 2020‑03‑31

URL http://id.nii.ac.jp/1160/00002005/

Teaching Traditional Japanese Culture in English: Cultural Distance and Cognitive Load in EMI and CLIL Contexts

David K. Groff

Meiji University

Reference Data:

Groff, D. (2020). Teaching Traditional Japanese Culture in English: Cultural Distance and Cognitive Load in EMI and CLIL Contexts. In K. Tanaka & D. Tang (Eds.), Multicultural Japan - Research and Methodologies for Teaching Language and Culture. Nishinomiya: Otemae University.

Abstract

Although much recent attention has been on contemporary culture, Japan’s traditional and historical culture retains an enduring appeal, and also plays a significant role in Japanese studies offered in English. Depending on the target students and objectives of the classes, these courses may be Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) or English as a Medium of Instruction (EMI) environments. Each presents its own set of challenges for pedagogy. This paper will draw on ideas in evolutionary educational psychology based on the work of David Geary, the cognitive load theory precepts of John Sweller, Richard Mayer, and Roxana Moreno, and the cultural anthropology work of Edward Hall and Geert Hofstede, in an attempt to shed light on the difficulties in teaching traditional Japanese culture subject matter in English. In particular, when some of the material may be difficult even for local students in their native language, along with the relevance of cognitive load theory to the planning and execution of such courses.

近年、現代文化は研究の対象として注目を浴びているが、日本の伝統文化と歴史文化は永続的な魅力 を保持しており、英語で提供される日本研究でも重要な役割を果たしている。対象の学生とクラスの 目的に応じて、これらのコースは、内容と言語統合学習(

CLIL)もしくは英語による学術科目授業

(

EMI)となる。それぞれが教育学のための独自の課題を提示する。この論文は、

ディビッド・ギア リーの研究に基づいた進化的教育心理学のアイデアを基盤とする。ジョン・スエラー、リチャード・

マヤー、ロクサーナ・モレノなどの研究者の認知負荷理論の教訓、そして、エドワード・ホールとヘ ルト・ホフステーデの文化人類学の成果は、特に伝統的な日本の文化科目を英語で教えることの困難 さを明らかにした。特に、母国語でさえ理解が困難な場合、そのようなコースの計画と実行に対する 認知負荷理論の関連性があるりえると指摘する。

Background

Goals of English-language Instruction of Traditional Japanese Culture

Japanese culture as part of Japan's “soft power” and exploitable assets has received a great deal of attention in recent years. Due to the difficulties of learning the Japanese language — particularly the writing system with its thousands of

characters, which creates a significant barrier to learning to read — and the status of English as an international language of tourism and education, much of the transmission of information about Japanese culture is done through the medium of the English language. For this reason, there is more and more attention paid to programs at the university level focusing on the study of Japanese culture for the purpose of introducing it to a global audience. Within this a major focus tends to be offering English-languages courses in the field (MEXT, 2018).

While there has been a boom in the study of “Cool Japan” culture such as manga and anime, study of traditional and historical Japanese culture remains popular. There are two basic contexts for the teaching of traditional Japanese culture through the medium of English in Japan. Perhaps the most basic or obvious is the mode known by the abbreviation EMI, for "English as medium of instruction". In this mode, as the name implies, the English language is simply the tool used to communicate the content at hand, in this case the concepts of traditional Japanese culture. While it is often presumed that some incidental language learning (of English) will take place (Brown & Bradford, 2017), this is not a focus of the instruction (a certain amount of Japanese vocabulary will often also be an overt target of instruction). The assumption is that the students have the necessary competence in English to study the subject matter in that language at an educationally appropriate level, in whatever school context that might be.

These courses serve two primary functions in Japan. The more obvious one is to provide on-site access to Japanese culture studies to foreign students whose Japanese language ability is not yet sufficient to effectively learn the material directly in that language. The other is to give Japanese students, particularly those who intend to study abroad, an opportunity to have the experience of studying level-appropriate subject matter in English while still in Japan. Since the home culture is a relatively familiar subject, there is also a degree of comfort that makes the subject an appealing easing-in to English-medium learning (Brown, 2017).

The other context for the teaching of traditional Japanese culture in English in Japan is “content and language integrated learning” (CLIL). Unlike the EMI discussed above, CLIL — as the name implies — takes the language of instruction also as a target of learning. In addition to the subject matter of traditional Japanese culture, the coursework also has specific English-language-learning goals, which are absent in EMI. The goals can range from various vocabulary not necessarily directly connected to the subject matter, to pragmatic features, such as disagreeing politely in discussion, to appropriate written style for writing an academic research paper, for example.

Enter Cognitive Load Theory

In 2017 the Government of New South Wales, Australia, published a handbook entitled Cognitive load theory:

Research that teachers really need to understand, heralding widespread acceptance of the importance of this theoretical framework for instructional design. Based largely on the work of instructional-design specialist John Sweller and his colleagues, cognitive load theory posits the role of working memory (Baddely, 1992), and its limitations, as central to education. According to cognitive load theory, instructional processes that cause the information to be learned to exceed the working memory capacity of the learner are inefficient, as the additional information will be lost and have to be re- learned. The theory is also based on the well-established idea that long-term memory is organized into schemata, which

for purposes of recall and use in working memory function as single units (Anderson, 1977, 1978; Bartlett, 1932; Piaget, 1928). The automation of these schemata is also an important feature of learning.

Three types of cognitive load are identified, and described as intrinsic, extraneous, and germane (Sweller 2010;

Sweller, van Merrienboer & Paas 1998). Intrinsic cognitive load is created by the inherent complexity or abstract nature of material to be learned; it is also relative to the preexisting knowledge base of the learner — material that might have a high intrinsic load for a beginning learner can have a low load for an expert (Sweller, van Merrienboer & Paas 1998).

Extraneous cognitive load is that which does not lead to schema construction and automation. This can come from various sources depending on the individual and environment, but for pedagogical purposes, cognitive load theorists are concerned with extraneous cognitive load arising from instructional design (van Merrienboer & Sweller, 2005).

Some teaching and learning practices, in other words, simply are more efficient in terms of their requirements of working memory, and others waste precious memory space with the need to hold unnecessary items in memory. The third type of cognitive load, the germane, is the cognitive load involved in creating and automating schemata, i.e. the cognitive demands of learning itself (Sweller, van Merrienboer & Paas 1998).

There is some disagreement regarding whether all three are additive and that the total cognitive load is the sum of all three, or whether germane load is mainly a function of interaction with intrinsic load (Schnotz & Kürschner 2007;

Sweller 2010; Kalyuga 2011), but the most basic model posits that the load is cumulative (Paas, Renkl & Sweller 2003), and that even the “good” germane load can contribute to cognitive overload if the total exceeds the learner’s working memory capacity (Gerjets, Scheiter & Cierniak 2009). Good pedagogical practice, then, will carefully assess the cognitive burden placed by the material to be learned (intrinsic load) as well as the instructional formats (extraneous and germane loads) in order to avoid cognitive overload. In the same year as the publication of the New South Wales handbook, education researcher Dylan Wiliam, emeritus professor of educational assessment at University College London’s Institute of Education, declared that cognitive load theory was “the single most important thing for teachers to know” (2017).

These ideas have been the subject of extensive testing via randomized controlled trials, and the findings have been robust. For example, a meta-analysis of studies on the effectiveness of worked examples (one of the teaching practices believed to be sound based on cognitive-load considerations) found an effect size of 0.52 (Crissman, 2006).

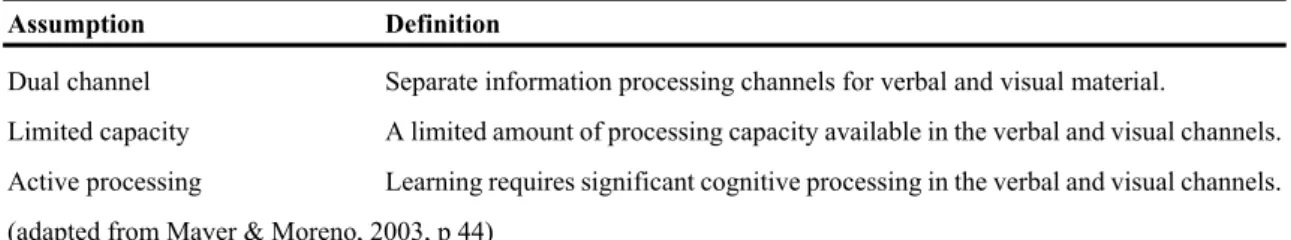

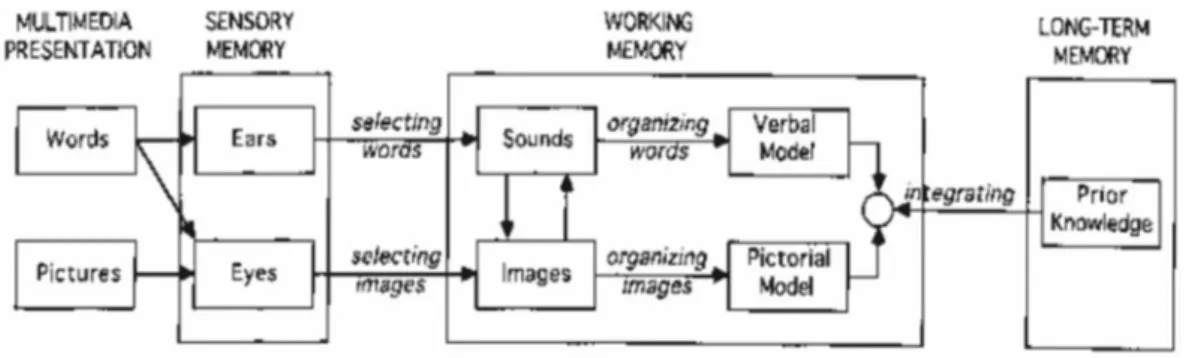

Roxana Moreno and her colleague Richard Mayer (1998, 2003) did extensive testing of cognitive load effects specifically in multimedia presentation. They found that learners have dual processing systems (“channels”) for auditory and visual input (see Table 1 & Figure 1).

Table 1. Three Assumptions About How the Mind Works in Multimedia Learning

Assumption Definition

Dual channel Separate information processing channels for verbal and visual material.

Limited capacity A limited amount of processing capacity available in the verbal and visual channels.

Active processing Learning requires significant cognitive processing in the verbal and visual channels.

(adapted from Mayer & Moreno, 2003, p 44)

Figure 1. Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning

(reprinted from Mayer & Moreno, 2003, p. 44)

Cognitive Load Theory has also found underpinnings in the work of evolutionary educational psychologist David Geary. Geary asserts that evolutionary pressures formed the human cognitive architecture such that it is to an extent inherently prepared to learn certain types of information, which he calls “biologically primary” knowledge (Geary 2002; Geary 2012; Geary & Berch, 2016). This includes various types of knowledge that he terms “folk knowledge”, such as “folk biology” and “folk physics” (see Appendix A).

Since the human cognitive architecture has evolved specifically to acquire such knowledge, it requires little or no explicit instruction. Other types of knowledge are biologically (or evolutionarily) “secondary”; since there are no built-in modules evolved to acquire these types of knowledge, they require specific and explicit instruction: these include reading and writing, and mathematics beyond simple counting (Geary, 2002). The logic goes, then, that such secondary knowledge carries an inherently larger intrinsic cognitive load, because it relies more on generalized cognitive architecture rather than “built-in” modules for specific domains of learning.

The implications of cognitive load theory are manifested in a variety of “effects”: in the worked example effect, the learner is presented with examples of problems which are pre-completed step by step, allowing the learner to build the relevant schemata with limited strain on cognitive limits. The split attention effect is created when visual representations and explanatory text are separated, requiring the learner to hold one or the other in working memory in order to integrate them, an unnecessary use of cognitive facilities., Verbal (auditory) input can, however, be effectively paired with visual presentation, but since reading text requires some of the same lexical-decoding processes as used for auditory processing, including text in the visual presentation will create more cognitive load; this is known as the modality effect. The redundancy effect, posits that for a given piece of information, one source is sufficient and redundant presentation of the information in other modes is actually detrimental to learning, as it engages unnecessary cognitive capacity. For example, auditory presentation alone has been found to be more effective than visual and auditory texts that were redundant (Craig, Gholson, & Driscoll, 2002; Mayer, Heiser, & Lonn, 2001). Further along in the learning process there is the expertise reversal effect, in which explicit instructional guidance that was beneficial for novices actually serves as a hindrance to those more expert (Kalyuga et al., 2003), presumably by interfering with their already-developed schemata. All of these cognitive-load effects have implications for pedagogy.

Concerns about cognitive load theory, particularly with regard to CLIL and EMI

Both Sweller (2017) and Geary (in Stevers, 2019) have waded into the subjects of EMI and CLIL, and both come down strongly against the teaching of content material in non-native languages, for reasons of inefficiency due to cognitive load. Sweller's research is centered around problem-solving fields such as mathematics and chess, with clearly defined rules, and Geary interprets second language as a "secondary" type of knowledge for which specifically evolved architectures do not function. However, there are significant differences between these models and research in SLA.

First of all, Geary's notion of first-language learning as "biologically primary" knowledge involving a specifically evolved and dedicated "module" in the brain sounds virtually identical to that of a "language acquisition device" (LAD) a la Chomsky or Krashen (1981), and there does not seem to be any particular reason to believe that the same type of cognitive architecture does not apply to the learning of languages beyond one's mother tongue(s). In fact, Geary seems to be invoking an interface between explicit learning about a language and (implicit, unconscious) competence in it, which has not been demonstrated to exist (Truscott, 2015). Therefore some caveats apply particularly when approaching CLIL with "cognitive-load-based" best practices in mind, since the language itself is partially the target of learning, and what is extrinsic load in other contexts becomes in effect germane load for the purposes of language learning, in that it aids in the building of schemata for that language, as implicit in Craik & Lockhart’s discussion of levels of processing (1972) and Laufer & Hulstjin’s findings on the effect of “involvement load” on vocabulary learning (2001).

In general criticism of cognitive load theory, the fact that there remains no direct measure of cognitive load is a significant concern (Schnotz & Kürschner 2007; de Jong 2010). In addition to this Moreno (2010) also wonders about the impact of learner motivation and beliefs on the effects of cognitive load. Nevertheless, the large body of robust experimental evidence for the basic tenets of cognitive load theory suggest that its principles should at least be considered when undertaking the teaching of Japanese Studies in English, particularly in the EMI context.

Cultural Distance (or Proximity)

Viewed through the lens of cognitive load theory, cultural distance (to use the term employed in business studies. In media studies essentially the same idea is expressed as “cultural proximity”, see for example Konara & Mohr, 2019, vs. Ksiazek & Webster, 2008) can be seen as a variance between the schemata (concepts) of the target culture, and the already-acquired schemata of a learner's home culture. Schemata which are similar or analogous to those already acquired are in turn easier to acquire (Hamilton, 2016), so it follows that learners whose home culture is more similar to the target culture will experience lower levels of cognitive load than those whose home culture is more different.

This factor will, in turn, have implications for best practices in pedagogy.

The question that then arises is how to assess the degree of cultural distance involved. With the widespread availability of mass media, contemporary cultures have come into increasing contact with one another, reducing somewhat the distance of unfamiliarity. The same cannot be said for traditional cultures, however. In fact, “traditional”

cultures might be defined precisely in opposition to those more affected by modernity and massive intercultural contact.

How, then, might the degree of variance between the cultures be reasonably assessed?

One very broad spectrum of cultures that is commonly employed is “high context” vs. “low context”. This conceptual framework was introduced by Edward Hall in the seminal 1976 work entitled Beyond Culture. In high- context cultures a large store of shared information (context) is assumed, so the encoding of the actual message carries much less explicit information; in low-context cultures the opposite is true — little information is assumed to be shared, so the communication itself must be very explicit and convey the necessary information virtually in its entirety (Hall, 1976). Hall’s cultural-anthropology approach is based on observation and analysis, and many assessments of various cultures’ degree of contexting are available (one popular one is Rosch & Segler’s 1987 visualization of Hall’s rankings).

A difference in degree of context between a home culture and the culture under discussion (in this paper traditional Japanese culture) would entail an implicit cognitive load, because of lacking the appropriate context (schemata). As an aside, the converse might also be true, due to the redundancy effect: when already-contexted information is also presented explicitly, it would create overload. In any case, Hall’s framework could, in broad strokes, predict in general how much additional cognitive load due to cultural distance/proximity a learner would be likely to encounter. For example, traditional Japanese culture partakes in significant degree of Chinese elements, and both cultures are high- context, so a Chinese student learning traditional Japanese culture can be predicted to encounter a generally lower cognitive load when studying the subject —although, in fact, they could even be subject to the expertise reversal effect if over-instructed (Pachman, Sweller & Kalyuga, 2013).

Hall’s framework, though widely used, has its detractors, however, mostly because it lacks a strong empirical basis (see for example Cardon, 2008). For a more fine-grained and data-based framework, the work of the Dutch researcher Geert Hofstede provides another useful set of tools. In Culture’s Consequences (Hofstede, 1981, 2001) and Cultures and Organizations (Hofstede, 1991; Hofstede, Hofstede & Minkov, 2010), Hofstede and his colleagues set out a set of six “dimensions” of culture: “power distance”, “individualism”, “masculinity”, “uncertainty avoidance”,

“long-term orientation”, and “indulgence vs. restraint”. Rather than being based on observation, like Hall’s frameworks, these dimensions were arrived at by the analysis of enormous amounts of raw data, specifically employee responses to internal surveys at IBM, where Hofstede worked for many years and added to by the World Values Survey assessed by Minkov (2012). Based on the relevant data, scores for each dimension for each country/culture in question were assigned, and these are listed in tables and plotted in charts in Hofstede’s and Hofstede et al.’s work. Kogut and Singh (1988) then aggregated the scores for the dimensions (then still five, “indulgence vs. restraint” being added later) into cultural distance scores for each pair of countries. This proved to be a very popular point of reference, and remains the most widely used index for the measurement of cultural distance in the disciplines of international business and management. This index has also come under criticism (Konara & Mohr, 2019), but may be useful enough to roughly assess cultural differences in a student population of mixed cultural backgrounds. For a more detailed comparison, the

“Hofstede Insights” website offers an interactive comparison of scores across the six dimensions, for up to four countries at a time (Hofstede, n.d.). This level of specificity may not be necessary for purposes of gauging cultural distance in order to adapt instruction to align with cognitive-load limits, but can be helpful for the teachers of multicultural classes to negotiate other intercultural issues that may arise with their students.

None of these tools is actually designed to measure aspects of a “traditional” culture, per se — they analyze

contemporary or at least relatively modern iterations of the cultures in question. However, it seems reasonable to assume that modern Japanese culture retains a significant degree of its traditional culture in its values as they are measured by these tools. Therefore, these measures should still provide a roughly accurate idea of the cultural distance/proximity between a given student’s home culture and traditional Japanese culture. If we take “traditional Japanese culture” to mean mainly that established and in practice prior to the Meiji Restoration and the ensuing large-scale adoption of many European and North American beliefs, values, and practices in Japan, then it is likely that assessments of cultural distance between that traditional culture and the contemporary home cultures of the students, which are the operative ones in this situation, need to be adjusted upward (i.e. larger cultural distance).

Linguistic Competence

One further assumption is that non-first-language presentation of material to be learned, in either CLIL or EMI contexts, carries an inherently higher intrinsic cognitive load, and that the lower the learner’s competence in the language of presentation, the higher that load will be. This is the crux of Sweller and Geary’s objections to EMI and other

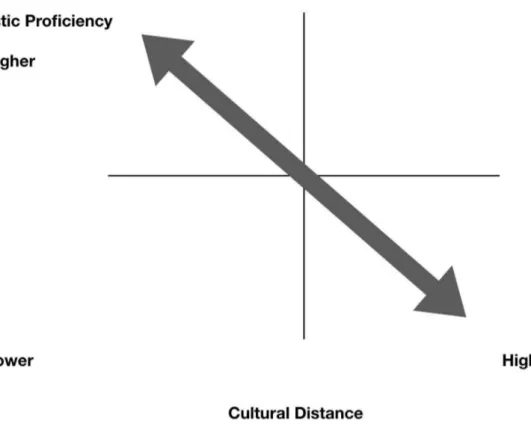

“immersion” contexts. Moreover, the effect on cognitive load of cultural distance and linguistic competence will be cumulative. To some extent, in English-language teaching of traditional Japanese culture, this phenomenon will actually have a balancing effect: native speakers of English, and highly proficient users of English (often from European and European-influenced countries with a large cultural distance to Japan) will encounter less cognitive load due to the language of instruction, but more intrinsic load due to the lesser degree of analogous cultural structures (schemata).

Conversely, Japanese students (as well as those from neighboring East Asian countries) who may have somewhat less proficiency in English will experience a higher cognitive load linguistically on account of the language medium. The content itself, in this case, will have a lower intrinsic load due to a greater degree of familiarity with some or much of the material, or analogous cultural concepts. However, there may be students with “the worst of both worlds”, i.e. a somewhat lower level of proficiency in the language of instruction and a home culture with a large cultural distance from Japan’s.

Conclusions and Recommendations

While cognitive load theory has mostly been applied in instructional design with reference to first-language learning and training, and measures of cultural distance/proximity have mainly had their uses confined to business/management and media studies respectively, when taken together both have clear application to the teaching of Japanese cultural studies through the medium of English. To begin with, in order to apply cognitive load theory and cultural-distance implications effectively to the teaching of traditional Japanese culture in EMI or CLIL environments, the instructor must gauge: a) the learners’ home cultures’ cultural distance from Japanese culture, b) their previous familiarity with the material to be learned, if any, c) the linguistic competence of the learners in the language of instruction, and d) the ratio of importance given to (English) language learning vs. learning the content material.

Probably the biggest adaptation that may be necessary is one of expectations regarding the scope and quantity of material to be covered. Depending on the linguistic competence and cultural distance of the students, cognitive-load limits may place restrictions on what can be reasonably expected of them, as seen below in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Reasonable Expectations for Scope and Quantity of Material Covered (created by author)

Thus, instructors should have some measure of each of these ranges: their students’ general linguistic proficiency in English (for which various preferences will apply), their cultural distance/proximity to traditional Japanese culture, and previous knowledge of the subject, and adapt instruction appropriately. The latter ranges can be assessed with surveys (see Appendix B) and the use of the cultural distance models and indices mentioned previously. Low levels of language proficiency may be adapted to with degrees of scaffolding (vocabulary building, simplification of materials, etc.), but a combination of lower language proficiency and higher cultural distance will probably require reducing the amount of material to be covered.

Higher language proficiency but also larger cultural distance will imply a variety of pedagogical adaptations, including the maximal activation and leveraging of paralinguistic (visual-conceptual) schemata. To this end, rich, multimedia presentation methods exploiting both visual and auditory channels should be employed, but while considering the possibility of the redundancy effect. Texts with shorter “chunks” of material are preferable. Longer texts can be adapted by breaking them up. Glossing should be available, and in EMI contexts it should be as immediately accessible as possible. For EMI classes with mixed L1s, digital versions of texts are optimal, as they generally allow for instantaneous look-up of unfamiliar vocabulary in their native language, which can greatly reduce cognitive load by eliminating the need for visual scanning of reference sources. Finally, Bloom’s Taxonomy can be used to assess the cognitive load of various kinds of activities. Higher-order activities may require extra linguistic or conceptual scaffolding such as glosses, expanded pictorial components, and increased segmenting to avoid cognitive overload — some ideas for how to do this specifically in an ELT context can be found in Vesty (2017).

There is undoubtedly much more to be learned about the nature of cognitive load itself, and how it interacts with cultural distance. It is certain, however, that the intrinsic cognitive load of learning about traditional Japanese culture is significant, even for most Japanese students; it seems likely that consideration of how to reduce extraneous cognitive load in the presentation of that material will be rewarding both for the students and the instructor.

Bio Data

David K. Groff is a senior assistant professor at Meiji University’s School of Global Japanese Studies, where he teaches Traditional Japanese Culture in English. He is interested in translation studies and the interactions between spiritual, aesthetic, and martial traditions in historical Japanese culture. His publications include The Five Rings:

Miyamoto Musashi’s Art of Strategy (Watkins Press, 2012), and “The ‘Art’ of the Martial: the Role of Aesthetics in the Appeal of Budō” (Japanese Academy of Budo, 2018). <dkgroff@meiji.ac.jp>

References

Anderson, R. (1977). The notion of schemata and the educational enterprise: General discussion of the conference. In R. Anderson, R. Spiro & W. Montague (eds), Schooling and the acquisition of knowledge, Hillsdale N.J.:

Erlbaum, 415-431.

Anderson, R. (1978). Schema-directed processes in language comprehension. In A. Lesgold, J. Pellegrino, S. Fokkema

& R. Glaser (eds), Cognitive psychology and instruction, New York: Plenum, 67-82.

Baddeley, A. (1992). Working memory. Science 255: 556-559.

Bartlett, F. (1932). Remembering: A study in experimental and social psychology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, H. (2017). Getting started with English-medium instruction in Japan: Key factors in program planning and implementation, Module 3: Developing English-medium instruction programs in higher education in Japan:

Lessons learned from program implementers. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Birmingham.

Brown, H., & Bradford, A. (2017). EMI, CLIL, & CBI: Differing approaches and goals. In P. Clements, A. Krause, &

H. Brown (Eds.), Transformation in language education. Tokyo: JALT.

Cardon, P. (2008). A critique of Hall's contexting model: A meta-analysis of literature on intercultural business and technical communication. Journal of Business and Technical Communication 22: 399.

Craig, S. D., Gholson, B., & Driscoll, D. M. (2002). Animated pedagogical agents in multimedia educational environments: effects of agent properties, picture features, and redundancy. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(2), 428-434.

Craik, F., & Lockhart, R. (1972). Levels of processing: A framework for memory research. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal behavior 11: 671-684.

Crissman, J. (2006). The design and utilization of effective worked examples: A meta-analysis, unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Nebraska, Lincoln N.E.

De Jong, T, (2010). Cognitive load theory, educational research, and instructional design: Some food for thought.

Instructional Science 38 (2): 105-134.

DeLeeuw, K. & Mayer, R. (2008). A comparison of three measures of cognitive load: Evidence for separable measures of intrinsic, extraneous, and germane load. Journal of Educational Psychology 100 (1): 223–234.

Geary, D. (2002). Principles of evolutionary educational psychology. Learning and Individual Differences 12:

317–345.

Geary, D. (2012). Evolutionary educational psychology. In K. Harris, S. Graham, & T. Urdan (Eds.), APA educational psychology handbook (Vol. 1, pp. 597–621). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Geary, D. & Berch, D. (2016). Evolution and children’s cognitive and academic development. In D. Geary & D. Berch (Eds.), Evolutionary perspectives on child development and education (pp. 217–249). Switzerland: Springer.

Gerjets, P., Scheiter, K. & Cierniak, G. (2009). The scientific value of cognitive load theory: A research agenda based on the structuralist view of theories. Educational Psychology Review 21 (1): 43-54.

Granholm, E., Asarnow, R., Sarkin, A. & Dykes, K. (1996). Pupillary responses index cognitive resource limitations. Psychophysiology 33 (4): 457–461.

Hamilton, Carole. (2016). Critical Thinking for Better Learning: New Insights from Cognitive Science. New York:

Rowman & Littlefield.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations. Second Ed. New York: Sage Publications.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. New York, NY:

McGraw Hill.

Hofstede (n.d.). Country comparison six dimensions. Retrieved from https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country- comparison/

Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive load theory: How many types of load does it really need? Educational Psychology Review 23, (1):1-19.

Konara, P., & Mohr, A. (2019). Why we should stop using the Kogut and Singh Index. Managment International Review 59: 335–354.

Kogut, B., & Singh, H. (1988). The effect of national culture on the choice of entry mode. Journal of International Business Studies 19 (3): 411–432.

Krashen, S. (1981). Second language acquisition and second language learning. New York, NY: Prentice-Hall.

Ksiazek, T., & Webster, J. (2008). Cultural proximity and audience behavior: the role of language in patterns of polarization and multicultural fluency. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 52 (3): 485-503.

Laufer, B. & Hulstjin, J. (2001). Incidental vocabulary acquisition in a second language: The construct of task-induced involvement. Applied Linguistics 22 (1): 1-26.

Martin, A. (2016). Using Load Reduction Instruction (LRI) to boost motivation and engagement, British Psychological Society, Leicester UK.

Mayer, R., Heiser, J. & Lonn, S. (2001). Cognitive constraints on multimedia learning: when presenting more material results in less understanding. Journal of Educational Psychology 93(1), 187-198.

Mayer, R., & Moreno, R. (1998). A split-attention effect in multimedia learning: Evidence for dual processing systems in working memory. Journal of Educational Psychology 90 (2): 312-320.

Mayer, R., & Moreno, R. (2003). Nine Ways to Reduce Cognitive Load in Multimedia Learning. Educational Psychologist 38(1), 43–52.

MEXT (Japan Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology). (2018). Top global university project.

Retrieved from https://tgu.mext.go.jp/en/about/index.html

Minkov, M. (2012). World values survey. In The Wiley‐Blackwell Encyclopedia of Globalization, G. Ritzer (Ed.) doi:10.1002/9780470670590.wbeog840

Moreno, R. (2010). Cognitive load theory: More food for thought. Instructional Science 38, (2): 135-141.

Pachman, M, Sweller, J. & Kalyuga, S. (2013). Levels of knowledge and deliberate practice. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied 19 (2): 108-119.

Rosch, M., & Segler, K. G. (1987). Communication with the Japanese. Management International Review 27: 56-67.

Schnotz, W. & Kürschner, C. (2007). A reconsideration of cognitive load theory. Educational Psychology Review 19 (4): 469-508.

Stevers, J. (Producer). (2019, March 20). Podagogy [Audio podcast] Season 5 Episode 8: Knowledge with Professor David C. Geary. Retrieved from https://www.tes.com/news/why-child-led-learning-does-not-work-and-what- you-should-do-instead

Sweller, J. (2010). Element interactivity and intrinsic, extraneous and germane cognitive load. Educational Psychology Review 22 (2): 123-138.

Sweller, J. (2017). Cognitive load theory and teaching English as a second language to adult learners. Contact (TESL Ontario’s magazine). http://contact.teslontario.org/cognitive-load-theory-esl/

Sweller, J., van Merrienboer, J & Paas, F (1998). Cognitive architecture and instructional design. Educational Psychology Review 10 (3): 251-296.

Truscott, J. (2015). Consciousness and second language learning. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

van Merrienboer, J. & Sweller, J. (2005). Cognitive load theory and complex learning: Recent developments and future directions. Educational Psychology Review 17 (2): 147-177.

Vesty, M. (2107). Using Bloom’s taxonomy to measure your lessons: critical thinking and material design.

Medium.com. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@mattvesty/using-blooms-taxonomy-to-measure-your- lessons-critical-thinking-and-material-design-8c45b6b8b373

Wiliam, D. (2017). I've come to the conclusion Sweller's Cognitive Load Theory is the single most impor tant thing for teachers to know <http://bit.ly/2kouLOq>, tweet, viewed 24 March 2017, <https://twitter.

com/dylanwiliam/status/824682504602943489>.

Appendix A

Premises and principles of evolutionary educational psychology Premises

(1) Natural selection has resulted in an evolved motivational disposition to attempt to gain access to and control of the resources that have covaried with survival and reproductive outcomes during hominid evolution.

(2) These resources fall into three broad categories: social, biological, and physical.

(3) Cognitive systems as well as inferential and attributional biases have evolved to process information these domains and to guide control-related behavioral strategies. The combination of cognitive, inferential, and attributional systems defines folk psychology, folk biology, and folk physics.

(4) Children are biologically biased to engage in activities that recreate the ecologies of human evolution. The accompanying experiences interact with inherent but skeletal cognitive and brain systems that define folk psychology, folk biology, and folk physics, and flesh out those systems such that they are adapted to the local ecology.

Principles

(1) Scientific, technological, and intellectual advances emerged from the motivational, cognitive, and inferential systems of folk psychology, folk biology, and folk physics, as well as from other evolved domains (e.g., number and counting). These advances result in a gap between folk knowledge and the theories and knowledge base of the associated sciences and disciplines.

(2) Schools will emerge in societies in which scientific and technological advances create a gap between folk knowledge and the competencies needed for successful living (e.g., employment) in the society. The function of schools will be to organize the activities of children such that they acquire the competencies that close the gap between folk knowledge and the occupational and social demands of the society. These academic competencies are termed biologically secondary abilities and are built from the primary (i.e., evolved) cognitive systems that comprise folk psychology, folk biology, and folk physics, as well as other evolved domains (e.g., number).

(3) Children are innately curious about and motivated to actively engage and explore social relationships and the environment, biases that are directed toward information and activities associated with folk knowledge. The motivational disposition to engage in activities that will develop folk knowledge will often conflict with the need to engage in activities that will lead to the mastery of academic competencies.

(4) The inherent cognitive systems and child-initiated activities that foster the development of primary abilities, such as language, will not be sufficient for the acquisition of secondary abilities, such as reading and writing.

It is predicted that the need for instruction will be a direct function of the remoteness of the secondary ability to the supporting primary systems.

(Geary, 2002, p. 328)

Appendix B

Sample Pre-course Assessment Survey Questions For foreign students:

- Describe your upbringing and the society you grew up in.

- How long have you been in Japan?

- How would you rate your knowledge of Japanese culture in general? How about traditional Japanese culture?

- What made you decide to study in Japan?

For Japanese students:

- Why do you want to study Japanese culture in English?

- How would you rate your knowledge of traditional Japanese culture?