Measurement of Life Stress by Means of The Multi‑Modal Questionnaire For Life Events

Survey And an Evaluation of Its Validity‑ (I)

著者 Ishikawa Akira

journal or

publication title

関西大学社会学部紀要

volume 24

number 1

page range 1‑46

year 1992‑09‑30

URL http://hdl.handle.net/10112/00022574

Measurement of Life Stress

By Means of The Multi-Modal Questionnaire For Life Events Survey And

an Evaluation of Its Validity- (I)

Akira Ishikawa

Abstract

By exam,n,ng various current behavioral medical studies concerning life stress and illness, the utility and the problems of life event scales in stress research are discussed. Furthermore, the relationships among three types of·constructs, namely stressful life events, personal dispositions and social supports, are discussed and six hypotheses integrating these three constructs into the life-stress are presented.

In order to develop a new instrument to measure life stress, a prelimi- nary survey was conducted on a heterogeneous sample of 88 adults. Among the stressful life events cited by this sample, the ones unique to Japan- ese were various problems related to the education of children and the problem in human relationships with relatives, neighbors and personnel at work places.

A new instrument called the Multi-modal Questionnaire for Life Stress Survey(MQLES)was developed based on the results of the above preliminary survey. It is named such because in a sense it is not just a mere inven- tory of stressful life events but it also contains the scales to measure

personal dispositions and social support. Therefore this questionnaire consists of four parts. Part A is a checklist of 33 physical and psycho- logical symptoms during the past month, Part Bis a checklist of 55 items concerning stressful life events during the past year, Part C is a 10- item scale designed to assess the Type A-B behavior patterns and a 8-item scale designed to measure the locus of control, and Part Dis a 20-item scale assessing social support.

In this first study, a total of 474 adults completed the MGLES. Of these 474 subjects, 221 (110 males and 111 females)were normal control subjects, 107 (48 males and 59 females)were neuropsychiatric outpatients, and 146 (1 13 males and 33 females)were peptic ulcer in and out patients. By utilizing SURYOKA II Ca kind of discriminant function)on this data, the standard weights to each item in Part A and B were obtained. A computation method was established for both the neurotic stress score and the psychosomatic stress score by using these weights. The percentages of subjects

diagnosed as "stress victim" by the above neurotic stress score were 1.36

% in the controls and 79.25% in the neuropsychiatric out patients. The percentages of subjects diagnosed as "stress victim" by the above psycho- somatic stress score were 5.88% in the controls and 70.55% in the peptic ulcer patients respectively. Other correlational and multiple regression analysis date are also presented.

Key words: life-stress process, measurement of life stress, personal dispositions, Type

A-B behavior pattern, locus of control, social support, neurotic stress score,

f.P

~:'£fis7- I-

v7-~m1.:mJi"7->ffl/J~~(f.Jffilvf~!:~JtL-t,

7- I-v7-~~l.::lol:t7-> Stressful Life Event .R,/tQ)5?J.JJficr .. ,ms!:ttlffii"7-> cc ti.:, :'£7;s;1. 1- v;1.ilBJijH.::lol:t7-> Stressful Life Event

c iffi!A(f.J~{tj::lo .t Vt±~(f.J;Jt:~~{tj: c v' ? =. -:,Q)j\'4/vl:fflt1:il;

It't.l•I.: ~,g.

~ti~ 7-> t.l•I.: mli" 7->

1'-? Q){Eililt!:~ff-1..Ato

.:.ti'i i:l.:lffl~

~ti "t"

~ t.:.:'£[is7' I- v 7-iJIIJ~.R,/tQ)r.,,m.?.\ !:J'lH!l

L,,t.l>-?7

7- I- Q):/j([fj't.,;tl1il!i-ti~Jfi(f.Jti..R./tQ)

lffl~ !:;i;jgj L- "t", 88~Q)-/J!'iitlvl:Al.:'A L-=ffilliill/il:i!i:!:ff-:,

t.:.o .:.Q)=ffilliill/il:i!i:Q)fi!i:ll!:1.:::£-:S 11,t r~ilfi(f.J:':Ei;s7-

I- v;1.~r.,,_J(MQLES) !:l\'4/vl:L-t.:o .:.Q)~r.,,~lil19$t.l•~l\'4/vl:~tit1t,7->o .!!~t:>ill/il:i!i:Ali:qii!i 1

:fJ }Jrd'l1.:~~ L-t.:$tf,$:,C,,J.ll!(f.J1.fE~331JHj

Q)f-.:r. ,y? 1) 7-1-, ill/il:i!i:B Iii/BJ~ 1 4:-rd'I 1.:::8 L-t.::':EitJ:

Q)/:IH~:$55:tJHI

Q)f-

.:r. ,y 7 I} 7- I-,ill/il:i!i: C

IH' -1 7"A - B ffl/J !: iJIIJ~i" 7->

t.: bl.> Q)10 lJHl .R./t c P'](f.J-7!-(f.J~ffilJMr/il !: illlJ~T

7-> t.: bl.> Q)8 ljUJ .R./t, ill/il:i!i: D lil±~(f.J:Jt:~~¥1= !:ill/iliti" 7->

t.:.bl) Q)

20lJHI i:

ib 7., 0ffi-lvf~l.::to11,t, .:. Q)Jfr.,,_!:221~Q)-/i1!'iit~A. 107~Q)ffl:Mi:MimIM*.m.#, 146 ~Q)WHtff iit1l.m.#1.::h([ff L-t.:o .:.ti ~=-Jffll1Q)7- ?' !:J:t~i"

7->c;ltl.:, -IJ!'iit# c ffl:Mi:MimIM*.f.#, :lo .t V-/Jl'iit# c r!llftHiit1l.m.#Q)rif!1.:~:1:ft=ffi!:~m L- t. ill/ilitll

1§1 Q)r.m]j.J !:;ttbl.> t, :tti.:eti:Mi

~(f.];1. I- v;1.{fsbC.,$)'1fil(f.J;1. I-

v7-~s!:;itbl.>7->7.75:\:!:~~L-t.:o :Miml1fil(f.J;1.

I- v7-~.?.\bC.-$1' 1fil(f.J;1. I- v 7-~.?.\I.: .t 7-> :iE~*li-/Jl'iit#i:98. 2%, ffl:Mi:MimIAA*.m.#i:80. 3%, 'i

t.:,C.-$1'1fil(f.J;1. I-v 7.

{isl.: .t 7-> :iE~*li-/J!1lt#i:79. 6%, l!ll{tHiit~.m.#i:60. 3%i:

;l;_,-:,t.:o -cQ)ft!l, £@1~5HJrl.:

.t 7->:'£i;s7'

I-VAi/Biffil.::lol:t 7->l±~(f.J:Jt:~~{tj:Q),r..lHt

CNlli!r L-t.:o

"'°-

? -r :

:'£1t;1.1-

v ;1.ilBJffi, :':Ert;1. 1-

v ;1.iJl1J~.R.1t, -MJA(f.J~fq:, i±~(f.J:Jt:~~#. ?' -1

7•A-

B rrlll, P'](f.J-71-(f.J~ffilJ#, :MimI1JE(f.J;1. 1- v A ~s. ,c.,,Jit1JE(f.J;1. 1- v A~.<!?:. ffl:Mi:MimI

AA*.m.#, t!llftHfl~.m.#

Acknowledgement

A number of individuals contributed in various ways to the completion of this study, to whom I would like to extend my appreciation.

I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Toshiaki Sakai of the Dept. of Neuropsychiatry of Osaka Medical College and also to Professor Hiroyuki Kagamiyama and Professor Kunio Okajima of Osaka Medical College for their guidance throughout.

I would also like to thank the following doctors for their assistance in recruiting subject patients.

For recruiting neuropsychiatric patients, all doctors of the Dept. of Neuropsychiatry, Osaka Medical College.

For recruiting peptic ulcer patients, Drs. Kawai and Kitamura at the Ohtori Gastro- intestinal Hospital.

For recruiting Meniere disease and other otorhinological patients, Prof. Matsunaga and Dr. Takeda of the Dept. of Otorhinolaryngology, Medical School, Osaka University, and Dr. Ogino at Ohtemae Hospital.

For adult asthma patients, Prof. Doi at Osaka Nursing College and Ms. Yamamoto at Tokyo Teishin Hospital.

All statistical analyses were conducted at the Kansai University Information Processing Center by using SAS and I would like to thank Dr. Shibata for lending me his expertise with the computer. Additionally, I must acknowledge the assistance of all my seminar students who interviewed each subject and collected the data.

This study was financially supported by a grant from Nihon Seimei Zaidan, and a

special thanks is offered to the people of the organization.

Introduction 1 Overview

Table of Contents

2 Utility of life events scales in stress research 3 Problems in stress research using life events scales Further methodological considerations

1 Personal dispositions related to the life stress process 2 Social conditions related to the life stress process 3 Hypotheses about the life stress process

Objectives of this study Preliminary survey

The Multi-modal Questionnaire for Life Events Survey (MQLES) Study I

Method 1 Subjects 2 Procedures Results

1 Discriminant analyses (SURYOKA II)

2 Comparisons between three subject groups on personal dispositions 3 Multiple regression analyses of the social conditions

Study II Method

1 Subjects 2 Procedures Results

Discriminant validity 2 Descriptive statistics 3 Factor analysis 4 Reliability Discussion References

Page 5 5

69 13 13 15 16

19 20

21 25 25 25 27 27 27 34 37

40

1 Overview

Introduction

Current behavioral medicine literature reveals an interest in the possible link between stressful life events and general medical or psychiatric illness (e.g. Bakal. 1979; Dohren- wend and Dohrenwend, 1974; Stone, Cohen and Adler, 1979). While the notion of a causal connection between stress and illness dates back to antiquity, it was not until well into this century that scientists began to study these phenomena systematically. ''That psychoso- matic medicine is still in its earliest infancy hardly needs emphasis" (Engel, 1978, p. 3).

The concept of a psychosomatic disorder is generally taken to refer to a type or category of illness that is associated primarily with psychological processes such as frustrating cir- cumstances, conflict, and/ or emotionally-taxing situations. However, the term psychoso- matic disorder is misleading in that it connotes the existence of a unique type of illness of psychogenic etiology distinct from other illnesses supposedly not relatable to psycho- logical processes. Moreover, it perpetuates a fallacious mind-body dualism, suggesting that one can describe a change in one of these systems and not the other (Bakal, 1979;

Engel, 1978; Sierles, 1980). Thus, many behavioral medicine researchers have emphasized that the majority of illnesses are multifactorial in origin, having both psychological and physical causes. (e.g. Bakal. 1979; Engel, 1978; Weiss, 1978). Additionally, Weiss sug- gests that, rather than trying to identify which illnesses are psychosomatic, researchers should address themselves to the questions of, "To what extent is the incidence or course of a given illness a function of psychological variables?,'' or ''Which psychological varia- bles are relevant for which patients?" (Weiss, 1978, p. 474). Such questions acknowledge that psychological variables may be more salient in the genesis of some illnesses than in others, and that certain psychological variables will be found to have more general relevance than others.

Historically two major orientations to the study of psychological components of somatic illness can be identified. The first orientation, the specificity hypothesis, derives from psychoanalysis and holds that specific unconscious conflicts are associated with psy- chological disorders (Alexander, French and Pollack, 1968). Other researchers within this framework have focused on the correlation between personality types and specific ill- nesses (Gentry, Shows and Thomas, 1974; Moos and Solomon, 1964).

In contrast, the generality approach posits that stress contributes to illness in general

rather than in specific ways. Most notable from a historical perspective is the work of Hans Selye (1956) who formulated the concept of the general adaptation syndrome, a generalized reaction of the body to stress, which he proposed was an ubiquitous concomit- ment of all illnesses. Additionally, Selye posited the existence of individual differences in what he termed adaptation energy, i.e., the finite amount of resistance or energy for com- batting stress (Selye, 1956).

More recently, investigators have attempted to demonstrate a temporal association between the onset of illness and the number and magnitude of recent events that require some form of adaptation on the part of the affected person. The assumption is that such events have a cumulative, precipitating effect on the timing, but not necessarily the type of physical or psychiatric disorders (Rabkin and Streunig, 1976). Toward this end, there have been attempts to quantify events in social environments that might be consensually perceived as stressful by large segments of the society at large. Perhaps the most fre- quently employed instrument is the Schedule of Recent Experience (SRE) developed by Holmes, Hawkins and Rahe (1957). This scale contains positive, negative, frequent, and rare occurrences. According to these investigators, each life change requires some form of adaptation which is in itself stressful. Too much demand for adaptation increases the chances of illness particularly in an already vulnerable individual, a position clearly retaining Selye's thinking (1956). Modification of the original SRE resulted in the creation of the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS) (Holmes and Rahe, 1967) which utilizes the assignment of weights to each item based on the ratings of a sample of judges, and the SRRS and others of the same type developed subsequently have been widely adopted as research instruments. At the same time, a variety of methodological problems concern- ing conceptualization and measurement of stressful life events have emerged from critical analyses of these studies. The utility of these instruments and the problems of these scales will be discussed in the next section.

2 Utility of Life Event Scales in Stress Research

This quantifiable, consensually derived approach to stress as measurable environmental input has contributed to recent broad-reaching investigations of the relationship between stressful life events and illness onset (e.g. Rabkin and Streunig, 1976; Rahe and Arthur,

1978; Stone, et. al., 1979).

For example, Gorush and Key (1974) found a higher incidence of complications of

pregnancy and parturiation in women who had experienced several life changes over the half-year prior to pregnancy, as opposed to women without such changes. A similar, earlier study demonstrated comparable results with the added finding that a lack of cop- ing skills appeared to exacerbate the effects of life stress (Nucholls, Cassel, and Kaplan, 1972).

Similarly, several studies of young adults have revealed a consistent moderate correla- tion between life change and illness. A group of researchers at the University of Kentucky have published a series of studies in this regard. The first (Marx, Garrity and Bowers, 1975) demonstrated a significant relationship between life change and the number of different illnesses experienced and the number of days in which a health problem was experienced during a 60-day period. Subjects were also administered the Langner 22-ltem Psychiatric Impairment Scale, which formed the basis for a later analysis.

A subsequent report, Garrity, Marx, and Somes (1977) focused on the results obtained with the Langner 22-item Psychiatric Impairment Scale. The authors proposed that the Langner scale would serve as a measure of the psychophysiological strain hypothesized to predispose a person to possible negative changes in health, in effects serving as the antecedent of health change. In their earlier report, life change was shown to be signifi- cantly associated with a variety of health outcome measures, one of which was the Langner scale. In this case, data were examined to compare the Langner Scale's ability to predict subsequent health status relative to recent life changes. The results revealed that while both life change and psychophysiological strain independently explained some of

,

the variance in health outcomes, the strain measure was the stronger predictor. The authors suggested that the strain measure, in effect, represented the joint effects of life change, subjective appraisal of change, and the individual's coping capacity.

In yet another report derived from this same sample of college students, Garrity, Marx, and Somes (1978) described the relationship between life change and the seriousness of later illness, as measured by the Seriousness of Illness Rating Scale (SIRS) (Wyler, Masuda, and Homes, 1968). The results revealed a statistically significant association (r = .33) between these of two measures.

Head (1979) investigated the relationship between personality style, stressful life events,

and subsequent depression in undergraduate subjects. Her results indicated that both

personality and the level of life events were important in predicting depression. Similar

findings were obtained by Johnson and Sarason (1978) who measured both depression

and anxiety, and by Lefcourt, Miller, Ware, and Sherk (1981) who focused on more enduring mood status including tension, depression, anger, fatigue, and confusion.

Moreover, this latter group of researchers also found that negative life events, rather than positive events, were responsible for the stress effect. Yunik (1979), who focused on general health problems, obtained data that likewise suggested that both the level of life events and personality style accounted for an important part of the variance in illness onset. His findings also were consistent with those of Lefcourt, et. al. (1981) regarding the salience of negative as opposed to positive life events in terms of effects on health.

More recently, Kuiper et. al. (1986) revealed an increase in depression level as negative life change scores increased by using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), the Life Expression Survey (LES), and the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS).

The life change and illness literature has also provided data bearing on specific medical/

psychiatric disturbances. The studies cited above are examples. Additionally, Araujo, Arsdel, Holmes, and Dudley (1973) studied the associqtion between psychosocial assets, life change, and the dosage of corticosteroids required to control chronic asthma. Life change was measured by the SRE, while the psychosocial assets of the 36 patients involved were assessed by th Berle Index (Bl) which measured the patient's ability to cope with dis- ease. The dependent variable was the average dosage of steroids recorded over a year's time, following the collection of the SRE and BI scores. These latter scores allowed for the separation of patients into four groups: high social assets, high LCU; high social assets, low LCU; low social assets, high LCU; and low social assets, low LCU. The results revealed that subjects with high social a;sets required small dosages of steroids regardless of their level of life change scores. Similar levels of steroid usage were reported by the patients in the low social assets and low life change category. However, patients in the low social assets and high life change category required a significantly higher level medica- tion than any other group. Thus, the results of this study implicated both the level of life change and psychological coping as variables related to the need for medication to control a specific chronic illness.

In terms of psychiatric illness, Myers, Lindenthal, and Pepper (1972) conducted a com-

munity survey measuring demographics, LCU scores, and self-reports of psychological

symptoms in a prospective study of psychiatric status. After a two year interval, their

measures were repeated and the data revealed that those individuals whose life changes

had increased over that time period demonstrated a deterioration of mental status, with

the converse occurring in persons who reported a decrease in their LCU level.

Turning to a specific type of psychiatric illness, Paykel and coworkers (Paykel, Prusoff and Myers, 1975) found that levels of recent LCUs occuring in the lives of hospitalised patients with depression were nearly twice those found, on average, in a non-patient con- trol group. Moreover, patients with a history of suicide attempts revealed four times the level of revent life events compared to the control subjects. These findings are buttressed by the fact that the data were not collected when the patients were depressed but several weeks later when clinical improvement had been noted. To gain further information, an attempt was made to classify the life events that signified loss (exits) as opposed to addi- tion (entrances) in person's lives requiring adaptation. They found that the former, but not the latter, differentiated the two groups, suggesting that it may be premature to minimize the role of loss in precipating depression as some authors (Woodruff, Goodwin, and Guze, 1974) have done.

3 Problems in Stress Research using Life Event Scales

In spite of the consistently positive findings reported above, recent reviews have cau- tioned that it is common for measures of stress and illness to show correlations of only .20 and .30 and to have standard deviations eight times greater than the mean, suggesting that life events alone account for only a minority of the variances in illness (Cleary, 1980;

Kobasa, 1979; Rabkin and streunig, 1976; Rahe and Arthur, 1978; Stone, et. al., 1979).

Moreover, it may well be that researchers have focused too narrowly on stressors that are dramatic and/or related necessarily to change. Lazarus (1981) discussed the results of a recent study that suggested that the cumulative effects of minor but more frequent daily events (hassles) may be a better predictor of health than life events as usually conceptual- ized. It is quite likely, he contends, that the effects of major life events occur not only due to their immediate impact but, at least as importantly, through the daily "hassles"

they provoke. The findings of Hong, et. al., on the effects of sustained stress (1979) would seem to support this contention.

In a similar vein, Lazarus (1981) and Maddi (1980) have underscored what they regard as the conceptual error of researchers who focus only on life events involving change.

They contend that much stress arises from chronic or repeated conditions of living such

as continuing tension in or dissatisfaction over an important area of one's life, isolation

and loneliness, existential concerns, and boredom. In fact, boredom and lack of meaning

or stimulation in life may give rise to what Maddi (1980) calls impact increasing behavior.

Finally, Head (1979) and Hong, et. al., (1979) have called for greater attention to the role an individual personality plays in bringing about life changes.

Conceptual issues aside, in may instances the data reviewed above must be viewed equivocally due to methodological shortcomings of the SRRS type of stress scales.

Many criticisms have been leveled at Holmes and Rahe's SRRS, most of them revolving around three general questions.

1) What populations of events should be studied?

2) Should event-specific weights be used to compute measures of recent life events?

3) If so, should these weights be person-specific or standard for all persons?

As to the problem of populations of life events, Dohrenwend & Dohrenwend (1984) suggest that there are at least three populations of life events:

1)events that may be confounded with the physical health and the psychiatric condition of the subjects, 2) events consisting of physical illness and injuries to the subjects, and 3) events whose occurrence are independent of either the subject's physical health or his/her psychiatric condition.

They advocate that the more a sample of events in a particular measure of stressful life events represents a summed mixture from these three event populations, as a general prin- ciple, the higher is the correlation with health indicators, and the more difficult it is to assess the etiological implications of a relationship between such a measure and various types of pathology. Thus, if an investigator's aim is to maximize the strength of the observed relationship between life events and illness, he/she should indiscriminately com- bine all populations of events or, better still, emphasize events that may be confounded with physical health and the psychiatric condition of the subject. If, however, the investi- gator's aim is to investigate the etiological role of life events, the various populations of events should be included but kept distinct in analyses of relations between life events and illness.

The position of this study is rather like the former one. Additionally, as mentioned later, various life events particularly unique to Japanese social lives are collected through the preliminary survey.

With respect to the second methodological question of event-specific weights to be used

to compute measures of recent life events, Holmes and Rahe (1967) introduced into

research on life stress and illness a procedure for quantifying the different amounts of

stressfulness of different life events with their SRRS. On its face this procedure seems reasonable, since it involves, for example, giving greater weight to the death of a child than to a son or daughter who has left home. However, critics have questioned whether event-specific weights offer any empirical advantage over simply counting life events, that is, giving each event a weight of one. Their most telling point is that the correlation between recent event scores based on the weighted sum of recent life events and scores based on the unweighted sum is likely to be so high that they will yield essentially the same results (Lorimer et al., 1979).

On the assumption of equal and positive correlation between events, this correlation is given by Ghiselli's formula:

V 1 +(k- l)r

ess' = (aw/W)

2(1-r) + 1

For this purpose, k is the number of events, r is the correlation between events, aw is the standard deviation of the event specific weights and

Wis the mean of these weights.

Even if r is very small,. 001, this formula, whether applied to Holmes and Rahe's event weights or those of the PERI Life Event Scale, predicts correlations on the order of .90 (Lorimer et al., 1979). If r is larger, the predicted correlation will be even higher.

Should we then infer that useful information is not provided by giving different weights to different life events?

This conclusion involves a premature simplification of the measurement of stressful life events. First, if an investigator concerns subsets of events rather than only the aggregate of all kinds of life events, the observed correlations in some subsets between weighted and unweighted scores may not be anywhere near .90. For example, an observed correlation between weighted and unweighted recent life event scores for the subset of events concern- ing childbearing and child rearing on the PERI Life Events Scale (Dohrenwend, B.S., et al., 1978) was .36. By Ghiselli's formula, if r is assumed to be .001, the correlation between unweighted and weighted scores for this subset of events was predicted to be .93.

Another problem with unweighted life event scores is the implicit assumption that

meaningful group differences in perceptions of the stressfulness of specific life events do

not exist. Yet there are meaningful differences in the judgments of the life events by

different social class and ethnic groups.

For example, "Death of spouse" is ranked to be the most stressful event by Caucasian Americans, Black Americans, Japanese, Danish, Swedish, and Hawaiians, while it is ranked fifth by Mexican Americans. "Divorce" is ranked to be the second most serious event by Caucasian Americans but its rank is third by Japanese, fourth by both Danish and Swedish, eighth by Hawaiians, tenth by Mexican Americans, and thirteenth by Black Americans in Rahe's study (1969). Additionally, Dohrenwend also found sex differences as well as social class and ethnic differences.

These findings argue against adopting unweighted scores, which preclude measuring group differences in the evaluation of the various aspects of life events.

Therefore, we may conclude that life-event weights are a useful research tool for some purposes and that event-specific weights may provide valuable information concerning subsets of different types of life events and group differences in perceptions and experiences of these events.

Thus, we come to the third question: whether event-specific weights should be person- specific or standard for all persons.

As part of the answer to the question of how to measure the stressfulness of particular life events, we hypothesized that the stressfulness of most life events is defined by a group norm (Hinkle, 1973, Redfield and Stone, 1979).

Therefore, a standard conception of the stressfulness of life events has been proposed.

But the stressfulness of a particular life event may vary from group to group and may change over time.

Given this conception of what is to be measured, one must choose between two differ- ent procedures that were designed to detect group differences in the stressfulness of life events. One calls for collecting direct ratings of life events from a representative sample of judges from different social groups as well as for applying statistical tests to determine whether these judgments indicate group differences in perceptions of particular events.

The other, descriptively labeled the effect-proportional measure of life events, proposes to develop weights for particular life events from observations of their relations to health indicators in different groups. The argument for the latter measure of life events is that it is more highly correlated with symptoms than any of a wide variety of other measures.

However, the effect-proportional measure of life events achieves a high correlation with

health indicators by including information about the vulnerabilities of individuals who

experienced a particular event as well as about the qualities of the event that determined

its effects on health. Therefore, the effect-proportional index might be used for purely predictive purposes, but is not suitable for etiological analysis. For that purpose, the procedure of obtaining ratings of qualities of events by judges chosen from the appropri- ate groups is more suitable since it is designed to provide a measure of group norms uncontaminated by other factors in the life stress process.

This study adopts the latter procedure but the event-specific weights are determined by the results of discriminant functional analyses as mentioned later, because more objective weight could be obtained by using such an analysis.

Further Methodological Considerations

In general, the magnitude of the relationship between stressful life events and illness has been found to be small. As noted earlier, Paykel (1974) estimated that despite a statistically significant association, no more than IOOJo of exits are followed by clinical depression. In their review of the literature on life events and illness Rabkin and Struening (1976) estimated from reporting correlations that stressful life events "may account at best for nine per cent of the variance in illness" (p. 115). Even more conservatively, on the basis of studies of U.S. Navy personnel, Rahe and Arthur (1978) estimated that the correlation between stressful life events occurring in a sixmonth period and illness reported over the next six months to one year was .12.

Given these findings, investigators have become concerned with explaining the substan- tial differences among individuals in responses to the same or similar life events.

One approach to solving this problem is to consider what personal dispositions may account for these individual differences.

1 Personal Dispositions Related To The Life Stress Process

Much has been learned in the last two decades from clinical observations, observations in natural settings, and experimental studies about effective psychological defense and coping responses to stressful events (Lazarus, 1966; Hamburg and Adams, 1967;

Horowitz, 1976). At the same time several hypotheses have been developed and tested

concerning the nature of individual differences in disposition that account for pathologi-

cal outcomes related to stressful life events.

One hypothesis, developed by Friedman and Rosenman (1974), is that persons with what they call Type A behavior pattern are more prone to develop heart disease than those with Type B behavior pattern. The Type A pattern is characterized by competitive achievement striving, a sense of time urgency, and a proneness to respond with hostility when frustrated. Further analyses of measures of AB behavior patterns suggest that they are multidimensional (Zyzanski and Jenkins, 1970) and that critical dimensions may relate to maintaining control over the environment (Matthews et al., 1977).

In a program of experimental studies related to the work of Friedman and Rosenman, Glass (1977) has shown that when persons prone to Type A behavior are faced with threatening events, they tend first to exert themselves strongly to achieve control.

However, if they fail to achieve control they are likely to react with extreme helplessness.

Glass's finding concerning the association of a helpless response with the Type A behavior pattern suggests a link between the work of Friedman and Rosenman and another conceptual theme in the research literature on stress and illness. A research group in the Dept. of Psychiatry at the University of Rochester developed a multistage model of stress-induced illness in which, given a stressful life event involving loss, those with a particular constitution or personality are prone to a helpless/hopeless response. This response is part of the giving up-given up complex which, in the presence of environmen- tal pathogens or constitutional vulnerability to disease, becomes the final common path- way to illness (Schmale, 1972).

Another hypothesis related to helplessness as a basis for individual differences in vul- nerability to stress-induced illness grows out of Rotter's (1966) social learning theory and his concept that individuals have a generalized expectancy concerning the extent to which they control the rewards, punishments, and, in general, the events that occur in their lives.

Rotter conceived this expectancy, which he labeled Locus of Control, as varying on a

dimension from internal to external. Persons at the extreme internal end of the locus of

control dimension expect to be in control of their life events to a high degree. In constract,

persons at the extreme external end of the locus of control expect that their life events

will generally be controlled by others or by fate. Although there is some controversy con-

cerning the relation of locus of control expectancy to vulnerability to pathology, the

hypothesis with the most extensive empirical support is that persons with an external locus

of control expectancy have greater proneness to pathology, particularly psychopathology,

than those with an internal locus of control expectancy (Lefcourt, 1976).

Laboratory research on physiological and psychological responses to stressful stimuli has supported the idea that individuals differ in the extent to which they repress awareness of threatening stimuli or, alternatively, are highly sensitive to such stimuli (Epstein and Fenz, 1967; Lazarus, 1966). Studies of these response styles in relation to recovery from illness suggest that repression leads to a better recovery (Brown and Rawlinson, 1976;

Cohen and Lazarus, 1973). At the same time, in the face of a threat against which the individual must act to escape or avoid harm,· repression would be dysfunctional. Some of the work on Type A and B behavior patterns suggests that Type A may involve repres- sion of responses to threatening stimuli (Glass, 1977).

One possibility, then, is that researchers from varied theoretical and empirical back- grounds may be converging on a central conception of factors in the individual that are related to stress induced illness. The person who exhibits what Friedman and Rosenman called the Type A behavior pattern may be seen as responding to loss with helplessness and be found to have an external locus of control expectancy. And his cognitive style may be to repress rather than to be sensitive to threatening stimuli and events. To date, however, these constructs concerning modes of stress-related responses have been deve- loped largely by separate disciplines so that their interrelationships have not been examined.

In studying the effects of personal control for each life event that a subject reported, Dohrenwend (1984) has probed the extent to which he or she anticipated and controlled occurrence of that life event. Their results so far suggest that individuals' perceptions of the extent to which they control the occurrence of their life events is influenced at least as much by characteristics of the particular event as by the personality of the individual.

Further work along this line will be necessary to determine the extent and stability of the effects of personality differences on the life-stress process.

2 Social Conditions Related To The Life Stress Process

Complementing efforts to find factors within the individual that affect his risk of illness

related to stressful life events are more recent attemps to identify social factors in the

individual's environment that affect this risk. One of the most influential hypotheses in

the recent literature on life stress states that social support mitigates the effects of stressful

events (Caplan and Killilea, 1976). Secondary analysis of data not specifically designed

to test this hypothesis has shown that highly stressful events combined with low social sup-

port are significantly more pathogenic than highly stressful events combined with high social support or less stressful events with either high or low social support (Cobb, 1976;

Eaton, 1978; Gore, 1978). Similarly, Theorell (1976) reported on the basis of a prospective study that stressful life events were followed by illness only for persons in a state of dis- cord and dissatisfaction.

As with life-event measures that confound objective events with symptoms of illness, social support measures that confound environmental supports with personal competence will probably be more strongly related to health indicators than social support measures not thus confounded. For etiological investigations the former are poor measures, however, since they do not provide an accurate assessment of the strength of the effect of social support as an element in the life-stress process.

Despite measurement problems, the results of studies of social support to date do indi- cate that a full understanding of individual differences in response to life events will not be achieved without examining the social situations in which these events are experienced in some detail.

3 Hypotheses About The Life-Stress Process

The great majority of studies of life stress and illness have been concerned primarily or exclusively with one or another of the three types of constructs that have been discussed above: stressful life events, personal dispositions and social conditions. The task now is to integrate these constructs into a single hypothesis about the life-stress process.

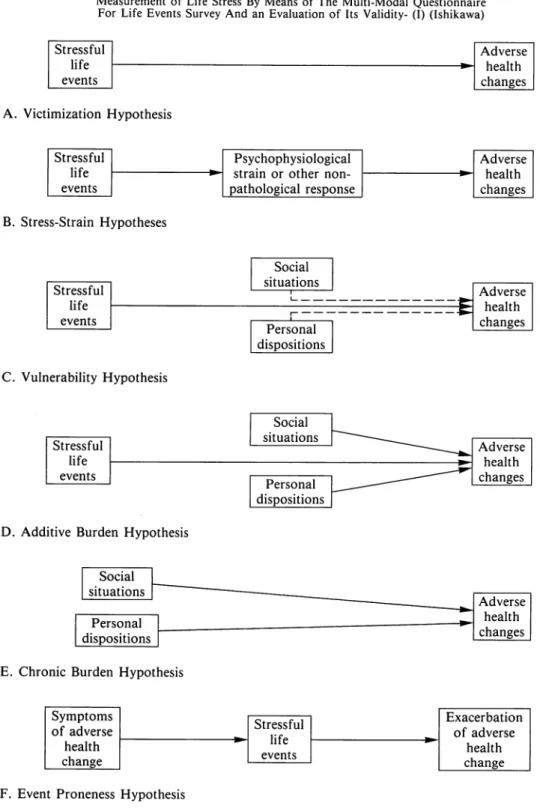

According to Dohrenwend (1984), the theoretical and empirical studies have developed at least six different hypotheses as shown in Fig. 1 in the next page.

The first hypothesis (A in Fig. 1) indicates that occurrence within a relatively brief time

of a number of severely stressful life events can cause adverse health changes. This model

was developed empirically in studies of extreme situations such as combat and concentra-

tion camps. It has been generalized to normal civil life in terms of a pathogenic triad of

concomitant events and conditions that involve physical exhaustion, severe physical ill-

ness or injury, loss of social support, geographical relocation, and the fateful negative

events over whose occurrence the individual has no control, e.g., death of a loved one

(B.S. Dohrenwend & B.P. Dohrenwend, 1978; B.P. Dohrenwend, 1979). It is also the

model that underlies and was supported by the early work of Holmes and Rahe and their

coworkers (Holmes and Masuda, 1974). This is called the victimization hypothesis.

Stressful life events

A. Victimization Hypothesis Stressful

life events

B. Stress-Strain Hypotheses

Stressful life events

C. Vulnerability Hypothesis

Stressful life events

D. Additive Burden Hypothesis

::.Psychophysiological strain or other non- pathological response

Social situations

L - - - -

, - - - - Personal

dispositions

Social situations

Personal dispositions

- Adverse health changes

Adverse health changes

Adverse health changes

Adverse health changes

I Social L

situations 1,---' ' Adverse

health

I Personal L - - - ---1 changes

dispositions I E. Chronic Burden Hypothesis

Symptoms

Stressful of adverse

life -

health

change events

F. Event Proneness Hypothesis

Fig. 1

Six Hypotheses About the Life Stress Process (Dohrenwend & Dohrenwend, 1984)

Exacerbation of adverse

health

change

The next hypothesis (B in Fig. 1) is exemplified by the work of Garrity, Marx and Somes (1977). They tested the model in a college student population using an instrument similar to Holmes and Rahe's Schedule of Recent Events to measure the changes entailed in recent life events, the Langner 22-item symptom scale to measure psychophysiological strain, and a number of general illness indicators. They found that when Langner scale scores were partialed out, correlations between life-event scores and illness indicators were sharply reduced, evidence that they interpreted as supporting their hypothesis that psy- chophysiological strain mediates the impact of life events.

Hypothesis B also describes the general form of Friedman and Rosenman's theory that certain self-esteem threatening life events elicit from predisposed individuals the Type A behavior pattern. But in a recent study, Malcolm and Janisse (1991) reported that the correlations between Type A score and Sarason's social support were found to be nega- tive. This hypothesis also underlies the Rochester group's theory that loss event elicit a helpless/hopeless response from some individuals that, in the presence of environmental pathogens or physiological vulnerability to a particular disorder, leads to illness. In a general form, it was proposed by Langner and Michael (1963) as the stress-strain hypothesis.

The third hypothesis (C in Fig. 1) indicates that stressful life events, moderated by preexisting personal dispositions and social conditions that make the individual vulnera- ble to the impact of life events, cause adverse health changes. A version of this hypothesis was developed by Rahe (1974). This hypothesis also underlies the literature on vulnerabil- ity involving conceptions such as coping ability (Hamburg and Adams, 1967), and social support (Caplan and Killilea, 1976; Cobb, 1976; Gore, 1978). It was also used by Zubin and Spring (1977) in their model of the etiology of schizophrenia and by Brown and Harris (1978) in their social model of the etiology of depression. This is the vulnerability hypothesis.

The fourth hypothesis (D in Fig. 1) states that, rather than moderating the impact of

stressful life events, personal dispositions and social conditions add to the impact of

stressful life events. This hypothesis is labeled the additive burden hypothesis. It received

empirical support in a study psychological symptoms by Andrews and his colleagues

(1978) and also proposed by Tennant and Bebbington (1978) as a better fit than the third

hypothesis to the data presented by Brown and Harris (1978) in their study of social fac-

tors in the etiology of depression. Recently Overholser, Norman and Miller (1990) report

similar results. They say although both life stress and social supports were significantly related to a variety of psychological symptoms, the interaction between these variables was not significantly related to psychological symptomatology, and life events and social supports were found to exert their effects independently. Their results for depressed inpa- tients argue against the stress-buffering hypothesis in favor of the direct-effects hypothe- sis of social supports, at least when applied to inpatient samples.

The fifth hypothesis (E in Fig. I) is called the chronic burden hypothesis and this is another and further modification of the third hypothesis. It proposes that stable personal dispositions and social conditions rather than transient stressful life events cause adverse health changes. This hypothesis was presented by Gersten and her colleagues (1977) as an explanation of changes in children's psychological symptom patterns. The method used in developing the empirical basis for this hypothesis is, however, open to criticism (Link, 1978).

The proneness hypothesis (F in Fig. I) raises the crucial issue of the direction of the causal relation between life events and symptoms of illness. It proposes that the presence of a disorder leads to stressful life events which in turn exacerbate the disorder. In empiri- cal studies this hypothesis was supported by a study of chronic mental patients (Fontana et al., 1972) but not by a study of neurotics (Tennant and Andrews, 1978). It should be tested for other chronic illnesses as well.

These alternative hypotheses about the life-stress process should be tested against each other.

Objectives of This Study

The objectives of this study are as follows:

I) To construct a questionnaire to examine life stress which is suitable for the Japanese, and which is easily administrable in the clinical field. To design this questionnaire so that it is useful for examination of the life-stress hypotheses by including items as to recent physical and psychological symptoms, personal dispositions and social condi- tions as well as stressful life events.

2) To devise a formula to obtain a neurotic stress score as well as a psychosomatic stress

score based on the results of the questionnaire.

3) To examine the discriminant validity of the stress scores by comparing the results in various patient groups who are considered to be stress victims with the ones in normal control subjects.

4) To examine the factorial validity of the questionnaire.

5) To examine the reliability of the questionnaire.

6) To examine the fitness of each of the hypotheses as to the life-stress process mentioned in the previous section.

Preliminary Survey

In order to develop a life stress questionnaire which is suitable for the Japanese, a preliminary survey was conducted in 1987. The subjects of this preliminary survey were 88 control adults in the Osaka area. Of these subjects, 43 were males and 45 were females with a mean age of 48 years (range: 31-69 years).

The subjects were asked to write the objects of their worries, fears, anxieties, distress etc in their daily lives for which they felt stressful. The Cornell Medical Index (CMI) was also administered to the subjects.

Among the stressful life events cited by this sample, the Japanese were the intensive responses to various problems related to the education of children and problems in human relationships with relatives, neighbors and personnel at work places.

With respect to the CMI, the number of subjects who checked more than 21 items of physical symptoms were 7 males (16.3%) and 12 females (26.7%). For the psychological symptoms, 12 males (27.9%) and 16 females (35.6%) checked more than 6 items respec- tively.

A new instrument called the Multi-modal Questionnaire for Life Stress Survey

(MQLES) was developed based on the results of this preliminary survey. Part A of the

MQLES was based on the results of the CMI and Part B of the MQLES was formed, by

basing it on the item pool obtained in the open ended question mentioned above.

The Multi-modal Questionnaire for Life Stress Survey

The Multi-modal Questionnaire for Life Stress Survey (MQLES) consists of four parts (Part A, B, C and D).

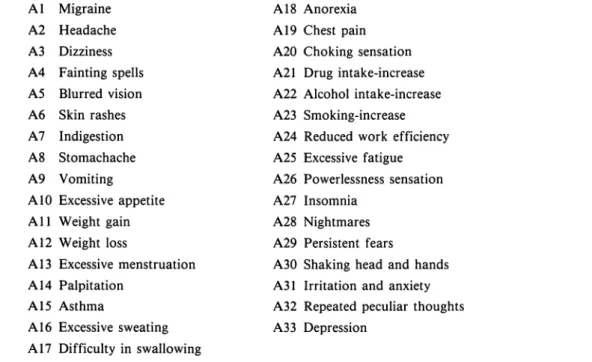

Part A is a checklist of 33 physical and psychological symptoms or complaints occuring during the past month as shown in Table 1.

Part B is a check list of 55 items concerning stressful life events or daily hassles during the past year as shown in Table 2.

Part C is a 10-item scale designed to assess the Type A-B behavior patterns and an 8-item scale designed to measure the locus of control. (Table 3 and Table 4)

Part D is a 20-item scale assessing social conditions as shown in Table 5.

This questionnaire is named to reflect the fact that it is not just a mere inventory of stressful life events but it also contains the scales to measure personal dispositions and social conditions.

Table 1

Physical and Psychological Symptoms or Complaints (Part A of MQLES) Al Migraine

A2 Headache A3 Dizziness A4 Fainting spells A5 Blurred vision A6 Skin rashes A7 Indigestion AS Stomachache A9 Vomiting

AIO Excessive appetite All Weight gain Al2 Weight loss

Al3 Excessive menstruation Al4 Palpitation

Al5 Asthma

A16 Excessive sweating A 17 Difficulty in swallowing

Al8 Anorexia Al9 Chest pain A20 Choking sensation A21 Drug intake-increase A22 Alcohol intake-increase A23 Smoking-increase A24 Reduced work efficiency A25 Excessive fatigue A26 Powerlessness sensation A27 Insomnia

A28 Nightmares A29 Persistent fears

A30 Shaking head and hands

A3 l Irritation and anxiety

A32 Repeated peculiar thoughts

A33 Depression

Table 2

Stressful Life Events or Daily Hassles (Part B of MQLES) Habit

B 1 Change in sleeping hours B2 Change in meal habits B3 Change in life habits B4 Change in life environment Family

B5 Wife's pregnancy B6 Wife's delivery B7 Wife's miscarriage BS New person in household

B9 Hospitalization of family member BIO Death of family member

Bl I Death of spouse B12 Child leaves home Bl3 Increase of family circle B14 Decrease of family circle B 15 Family discord

Education of Children B16 Child's entrance exam.

B17 Child's academic failure BIS Child's school refusal B19 Child's violence B20 Child's misdeed

B21 Child's major illness or accident B22 Arguments with child

Marital Relations B23 Got married B24 Wife got a job B25 Divorce

B26 Marital separation due to argument B27 Marital separation not due to

argument

B2S Troubles in sexual life B29 Spouse unfaithful

B30 Increased arguments with spouse

Household Economy B31 Decreased income B32 Decreased assets

B33 Loan more than 5 mill.yen B34 Loan less than

5mill.yen B35 Major financial difficulties Human Relationships

B36 Arguments with neighbors B37 Arguments with friends B3S Arguments with relatives B39 Decreased opportunities B40 Death of close friend B41 Decrease of close friends B42 Trouble with lover Work

B43 Retirement B44 Unemployment B45 New job

B46 Organizational change B47 Change in work conditions

B4S Change of work due to replacement B49 Promotion

B50 Argument with boss or coworker Others

B51 Minor legal violation B52 Jail sentence B53 Law suit

B54 Trouble in religion or in faith B55 Unfavorable conditions in

neighborhood

Table 3

A Brief Scale for the Measurement of Type A-B Behavior Pattern (Part C of MQLES) Do you find it difficult to restrain yourself from hurrying other's speech

(finishing their sentences for them)?

2 Do you often try to do more than one thing at a time (such as eat and read simul- taneously)?

3 Do you often feel guilty if you use extra time to relax?

4 Do you tend to get involved in a multiplicity of projects at once?

5

Do you find yourself racing through yellow lights when you walk at a crossing?

6 Do you need to win in order to derive enjoyment from games and sports?

7 Do you generally move, walk, and eat rapidly?

8 Do you agree to take on too many responsibilities?

9 Do you detest waiting in lines?

10 Do you have an intense desire to better your position in life and impress others?

Table 4

A Brief Scale for Measurement of Locus of Control (Part C of MQLES) 1 If I get into a car accident,

a I will think it depends mostly on my driving skill.

b I will think it depends mostly on the other driver.

c I will think it is mostly a matter of luck.

2 When I get what I want,

a it's usually because I worked hard for it.

b it's because of the people above me.

c it's usually because I'm lucky.

3 My life is determined by a my own actions.

b powerful others.

c accidental happenings.

4 Whether or not I become a leader a depends mostly on my ability.

b depends mostly on those in positions of power.

c depends on whether I'm lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time.

5 When I make plans,

a I am almost certain to make them work.

b I make sure that they fit in with the desires of people who have power over me.

c I do not plan too far ahead because many things turn out to be a matter of good or bad fortune.

a: internal scale, b: powerful others scale, c: chance scale.

Table 4

(continued)

6 How many friends I have

a depends on how nice a person I am.

b depends on whether important people like me or not.

c is chiefly a matter of fate.

7 When I look upon my

life,a I feel that I can pretty much determine what will happen in my life.

b I feel that my life is chiefly controlled by powerful others.

c I have often found that what is going to happen will happen.

8 Which of the following opinions is most close to yours?

a I am usually able to protect my personal interests.

b People like myself have little chance of protecting my personal interests when they conflict with those of strong pressure groups.

c Often there is no chance of protecting my personal interests from bad luck happenings.

a: internal scale, b: powerful others scale, c: chance scale.

Table 5

Items for the Social Conditions Survey (Part D of MQLES) DI Present Marital status

D2 Family members presently living together D3 Home ownership

D4 Occupation of yourself D5 Occupation of your spouse D6 Annual income of yourself

D7 Annual income of all your family members D8 Education

D9 Smoking habits DlO Alcohol drinking habits Dll Anamnesis

D12 Chronic disease

Dl3 Long-term absence by illness or accident

Dl4 Do you have a person to take care of you at least for a month if you are disabled by illness or accident?

Ifyes, who?

Dl5 Do you have a person who can look after you with tenderest care if you face mental trouble?

Ifyes, who?

Dl6 Do you have a person who helps you financially if you come to a deadlock?

If

yes, who?

Dl7 Number of supporters

Dl8 Availability of institutional support agencies

Dl9 Degree of association with neighbors

D20 Social group membership

STUDY I

Study I was conducted in 1988 and 1989 in order 1) to devise a formula to obtain a neurotic stress score as well as a psychosomatic stress score, and 2) to examine the effects of personal dispositions and social conditions on the life-stress process by MQLES.

METHOD

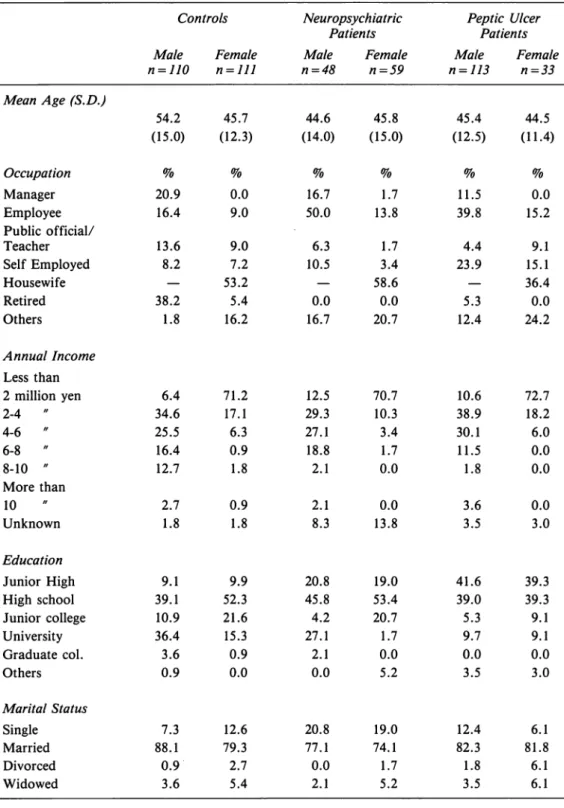

1 Subjects

The number of subjects was a total of 474 adults. Of these 474 subjects, 221 (110 males and 111 females) were control subjects, 107 (48 males and 59 females) were neuropsy- chiatric outpatients at the Osaka Medical College Hospital and 146 (113 males and 33 females) were peptic ulcer in and out patients at the Ohtori Gastro-Intestinal Hospital, Osaka.

The neuropsychiatric subjects were those outpatients who were diagnosed to be psycho- genic on the first interview by the medical doctors. About 90% of the patients were

"neurosis" but their diagnosed names varied in numerous cases as follows: Neurosis, Obsessive-compulsive neurosis, Conflict neurosis, Psychogenic reaction, Anxiety neurosis, Character neurosis, Psychosomatic neurosis, Delusional reactive, Depressive neurosis, Depression, Writer's cramp.

The peptic ulcer subjects were those outpatients who had already undergone an opera- tion on the stomach or the duodenum iri the previous three months or. those inpatients who were going to undergo such an operation on the stomach or the duodenum.

The demographic characteristics of the subjects are shown in Tobie 6.

oo~*•ra••$E~J•u• ■ 1&

Table 6

Demographic Characteristics of the Subjects

Controls Neuropsychiatric Peptic Ulcer

Patients Patients

Male Female Male Female Male Female

n=JJ0 n=lll n=48 n=59 n=ll3 n=33

Mean Age (S.D.)

54.2 45.7 44.6 45.8 45.4 44.5

(15.0) (12.3) (14.0) (15.0) (12.5) (11.4)

Occupation

% % % % % %Manager 20.9 0.0 16.7 1.7 11.5 0.0

Employee 16.4 9.0 50.0 13.8 39.8 15.2

Public official/

Teacher 13.6 9.0 6.3 1.7 4.4 9.1

Self Employed 8.2 7.2 10.5 3.4 23.9 15.1

Housewife 53.2 58.6 36.4

Retired 38.2 5.4 0.0 0.0 5.3 0.0

Others 1.8 16.2 16.7 20.7 12.4 24.2

Annual Income Less than

2 million yen 6.4 71.2 12.5 70.7 10.6 72.7

2-4 34.6 17.1 29.3 10.3 38.9 18.2

4-6 " 25.5 6.3 27.1 3.4 30.1 6.0

6-8 " 16.4 0.9 18.8 1.7 11.5 0.0

8-10 " 12.7 1.8 2.1 0.0 1.8 0.0

More than

10 " 2.7 0.9 2.1 0.0 3.6 0.0

Unknown 1.8 1.8 8.3 13.8 3.5 3.0

Education

Junior High 9.1 9.9 20.8 19.0 41.6 39.3

High school 39.1 52.3 45.8 53.4 39.0 39.3

Junior college 10.9 21.6 4.2 20.7 5.3 9.1

University 36.4 15.3 27.1 1.7 9.7 9.1

Graduate col. 3.6 0.9 2.1 0.0 0.0 0.0

Others 0.9 0.0 0.0 5.2 3.5 3.0

Marital Status

Single 7.3 12.6 20.8 19.0 12.4 6.1

Married 88.1 79.3 77.1 74.1 82.3 81.8

Divorced 0.9 2.7 0.0 1.7 1.8 6.1

Widowed 3.6 5.4 2.1 5.2 3.5 6.1

2 Procedures

The MQLES was completed by the 474 subjects. To devise a neurotic stress score, the SURYOKA II (a kind of discriminant analysis if the external criteria or the dependent variable is a qualitative rather than a quantitative data) was applied to the data of the con- trol subjects and the neuropsychiatric outpatients. To devise a psychosomatic stress score, the same analysis was conducted on the data from the controls and the peptic ulcer patients. In these analyses, the results of Part A (Symptoms/Complaints) and Part B (Stressful life events) were used.

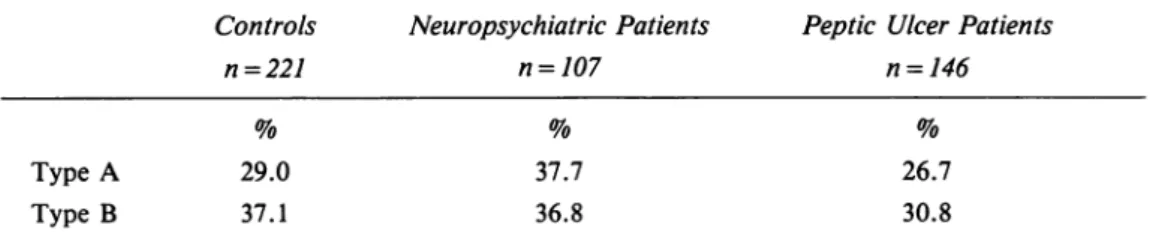

The comparisons were made between three subject groups to examine the effects of the personal dispositions (Type A behavior pattern and Locus of Control) on the life-stress process. The measurements for these personal dispositions were obtained by using the scales in Part C which were designed by the author.

The multiple regression analyses were used for the data analysis of 14-17 social condi- tion variables in Part D. To ascertain the direct and independent effects of these social conditions on the two health status indices, the regression coefficients were examined for each variable of the social conditions. The health status indices used in the analyses were

1)the membership of each subject groups (e.g. control vs neuropsychiatric or peptic ulcer patient), and 2) the number of symptoms or complaints reported by the subject.

RESULTS

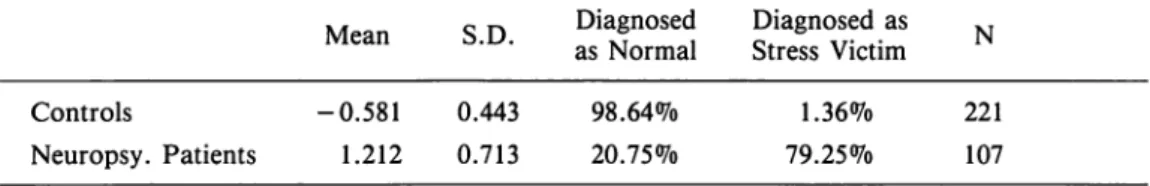

1 Discriminant Analyses (SURYOKA II)

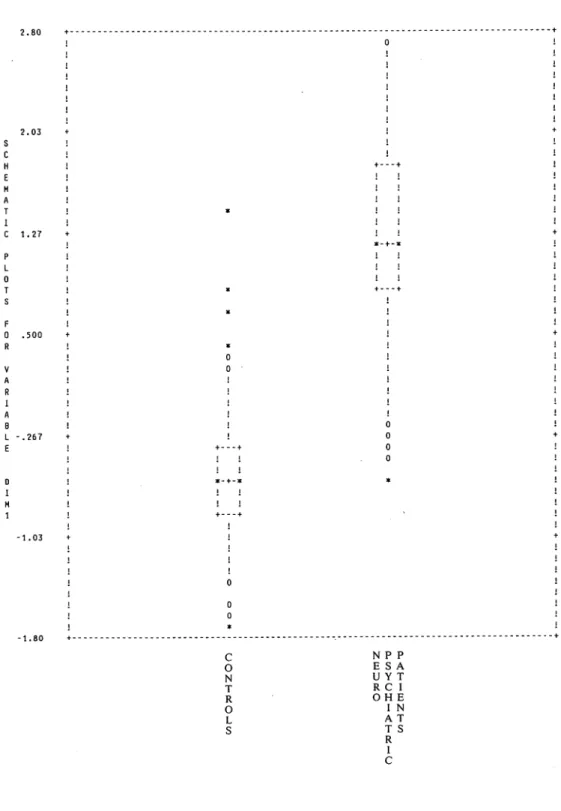

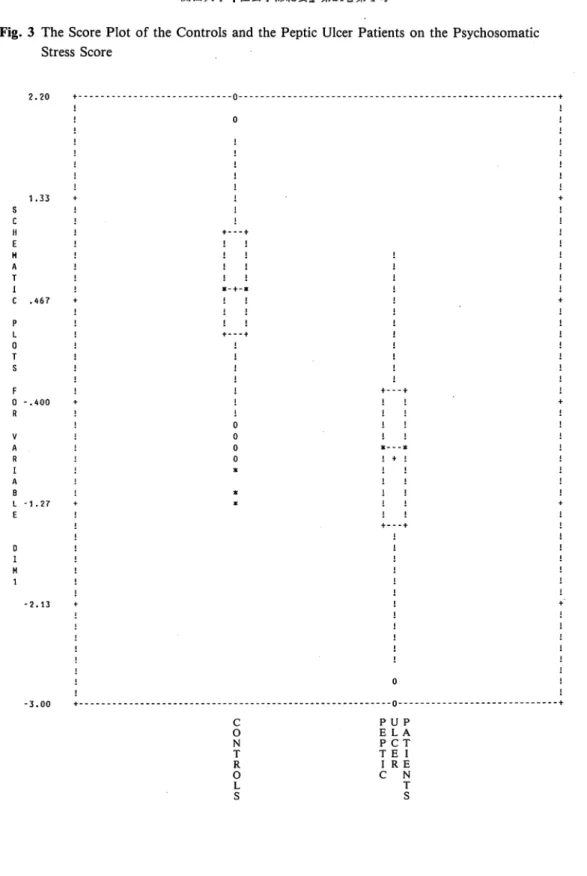

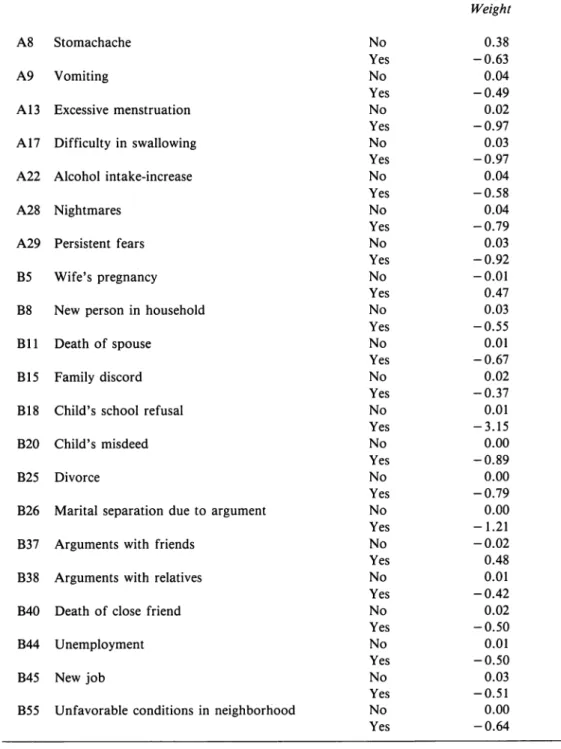

The results of SURYOKA II applied to the controls and the neuropsychiatric patients are shown in Fig. 2 and Table 7. The similar results for the controls and the peptic ulcer patients are shown in Fig. 3 and Table 8.

As seen in Table 7, the percentages of "right diagnosis" by the neurotic stress score were 98.60/o for the control subjects and 79.20/o for the neuropsychiatric out patients.

The percentages of "right diagnosis" by the psychosomatic stress score were 94.10/o for the controls and 70.60/o for the peptic ulcer patients as shown in Table 8.

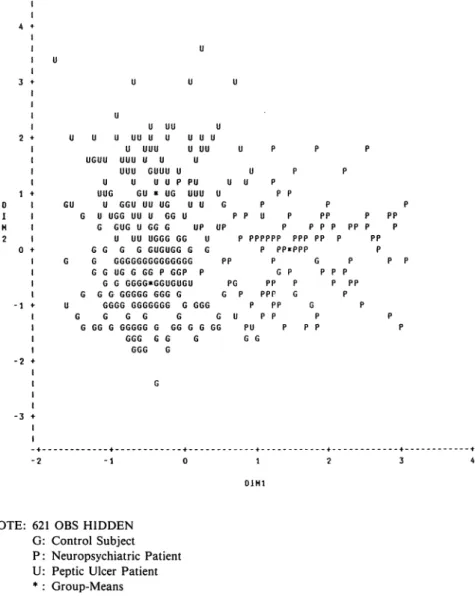

Fig. 4 shows the score scatter plot of all subjects in the frame of Dimension 1 (neurotic stress score) and Dimension 2 (psychosomatic stress score).

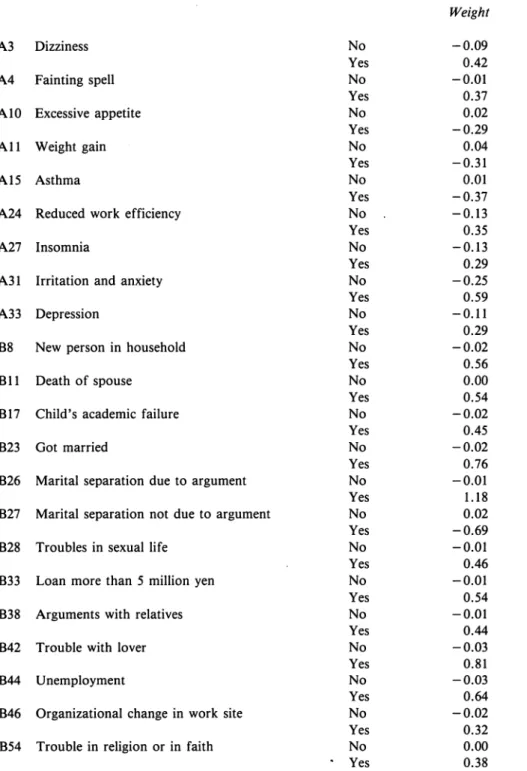

The neurotic stress score and the psychosomatic stress score were calculated by giving

weights to the items in Part A and B, which were obtained by the SURYOKA II analyses.

The salient variables (items) contributing to these scores and their weights are shown in Table 9 and Table 10.

For the neurotic stress score, the items which showed the biggest weight were "marital separation due to argument", followed by "trouble with lover", "unemployment", "got married", "new person in household", "death of spouse", "loan more than 5 million yen" and "child's academic failure".

On the other hand, the items which showed the biggest contribution to the psychoso- matic stress score were "child's school refusal", followed by "marital separation due to argument", "child's misdeed", "divorce", "death of spouse", "unfavorable conditions in neighborhood", "new person in household", "new job" and "unemployment".

It is noteworthy that the items relating to marital relations or human relations showed a strong discriminant power and that the items concerning financial problems did not con- tribute much to the psychosomatic stress score.

Table 7

The Means and the Standard Deviations of The Neurotic Stress Score and The Percentages of "Right Diagnosis" by The Score

Mean S.D. Diagnosed Diagnosed as as Normal Stress Victim N

Controls -0.581 0.443 98.640'/o 1.360'/o 221

Neuropsy. Patients 1.212 0.713 20.750'/o 79.250'/o 107

Table 8

The Means and the Standard Deviations of The Psychosomatic Stress Score and The Percentages of "Right Diagnosis" by The Score

Mean S.D. Diagnosed Diagnosed as as Normal Stress Victim N

Controls 0.568 0.618 94.120Jo 5.880'/o 221

Peptic Ulcer Patients -0.860 0.846 29.450'/o 70.550'/o 146

Fig. 2

The Score Plot of the Controls and the Neuropsychiatric Patients on the Neurotic Stress Score

H A T I C

0 T

F 0

V A R A 8

0 I H

2.80

+---+

0

2.03

+---+

*

1.27

+

*

• 500

- • 267

+---+

+---+

-1.03

0

-1. 80 +- - - ____________________ -. _______________________________________ + C

0 N T R 0 L

s

NPP ESA UYT OHE RCI I N AT TS R

I C