The Education of Linguistic Minority Students in the United States: A Case Study of Asian Immigrants

著者 TANAKA Keiko, 田中 桂子

volume 39

page range 87‑106 year 2011‑03‑30

その他のタイトル 米国における言語的少数派学生の教育―アジア系移 民を事例として―

URL http://hdl.handle.net/10723/1485

The Education of Linguistic Minority Students in the United States: A Case Study of Asian Immigrants

Keiko Tanaka

Abstract

Many higher education institutions across the world will continue to witness a diversification in the population of students in the 21st century. Among students from diverse backgrounds, a significant number will be linguistic minority students categorized as remedial in need of further academic literacy education in the mainstream language of the university. This is the case for a majority of immigrant students in the United States for whom English is a second or third language. All too often, these remedial English learner students are themselves blamed for their lack of academic preparation even though educational policies and practices in the elementary and secondary schools have often ignored their educational and linguistics rights and needs. Also, the English language instructors in the university are frequently asked to offset their academic deficit in a short time without adequate allocation of resources.

To date, however, there is a paucity of research conducted on these students, which can inform us about their gaps in knowledge and skills and about factors in their personal and educational backgrounds, which may influence their learning. Thus, the goal of this paper is to report on the findings of a study that investigated the academic literacy development of twenty linguistic minority students enrolled in developmental English courses at an ethnically diverse urban university in the United States. Central to the paper is the testimonials of the students about their educational experiences and the examination of a disturbing hypothesis, derived from observation of these students, that there exists a critical period for the acquisition of second language academic literacy among young adult language learners and that the rate and extent of this acquisition is linked to whether or not they were given an opportunity to enhance their first language (L1) literacy.

Introduction

As the pace of transnational migration of people prompted by globalization increases, some nations are becoming more linguistically diverse. Although many nations across the globe have a multilingual history, and embrace multilingualism as a cultural

heritage, some nations including the United States consider themselves monolingual despite the presence of a huge number of speakers of other languages. Hence, these nations tend to implement language policies and educational practices that do not endorse multi- or bilingualism. In fact, in the United States, educational institutions have preferred mainstreaming – the practice of immersing students who do not know English in regular classes where English is used as the instructional language with varying degrees of learning support—as a way to transition the linguistic minority students toward becoming English speakers based on a philosophy that learning English should be a priority for immigrants even if it means a loss of the mother tongue.1 Hakuta, a well-known Stanford University educator suggests that this practice is endorsed in the United States because many Americans are threatened by bilingualism (Zehr, 2010). Also, there is a widespread assumption that it is extremely difficult to learn a new language while maintaining and enriching the mother tongue even though as Grosjean (1982) argues, bilingualism and multilingualism is widespread in the world and have probably existed from the beginning of language in human history.2

In contrast, an alternative approach that places linguistic minority students in classes that use their mother tongue as the primary instructional language while letting them learn the majority language is a standard in nations including the Philippines, India, Canada, South Africa, and Switzerland that accept multilingualism.

It should be noted that the mainstreaming approach to language education taken by the United States goes against the 1992 United Nations’ Declaration on the Rights of Linguistic Minorities:

Article 1.1

States shall protect the existence of the national or ethnic, cultural, religious and linguistic identity of minorities within their respective territories and shall encourage conditions for the promotion of that identity.

Article 1.2

States shall adopt appropriate legislative and other measures to achieve those ends.

Article 4.3

States should take appropriate measures so that whenever possible, persons belonging to minorities have adequate opportunities to learn their mother tongue or have instruction in their

mother tongue.3 (UNHCHR)

It also goes against the Hague Recommendation on the Rights of Minorities issued by Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) which indicates that linguistic

minority students should receive education in the mother tongue:

For minorities, mother tongue medium education is recommended at all levels, also in secondary education. This includes bilingual teachers in the dominant language as a second language. Submersion-type approaches whereby the curriculum is taught exclusively through the medium of the State language and minority children are entirely integrated into classes with the majority are not in line with international standards. (OECE)

In fact, the policies that disable linguistic minority students from being educated in their mother tongue has brought about negative consequences which are more evident in the United States, the world’s top immigrant recipient nation than in any other country.

For example, educational data broadly show that decades of initiatives costing hundreds of millions of dollars have largely produced linguistic minority students who have virtually lost their mother tongues but have not acquired enough English to succeed in school. This is certainly the case in the state of California, which has one of the highest numbers of linguistic minority students. The results of the 2009-2010 California English Language Development Test (CELDT)4 indicate that of the 1,292,131 English learners enrolled in kindergarten through grade 12 in the state of California, for example, approximately 50 percent do not have sufficient proficiency level in English required to succeed in school (California Department of Education, 2010). At the university level, some estimates indicate that in the California State University system, nearly 60 percent of approximately 53,000 freshmen do not have sufficient proficiency level in English and/or math to succeed in the university (Chronicle of Higher Education, 2010).5

In short, the educational issues surrounding linguistic minority students in California show that researchers need to continue their investigative effort to recommend educational and policy solutions that can effectively address the needs and protect the human rights of linguistic minority students.

This paper reports on a study that examined key factors that have emerged in the past decades as those that influence the academic literacy development of linguistic minority students in a post-secondary institution in California. These factors include the amount and quality of English language instruction and support that the students were able to receive during kindergarten to grade 12 (K-12), and the relationship between the students’ mother tongue or first language (L1) literacy and second language (L2) literacy development. The study investigated whether these students, given the educational preparation they had received in K-12 and their personal backgrounds, could acquire college level academic literacy skills within a one-year developmental6 English program

offered in the university. Specifically, this study addressed the following questions:

1. How long does it take linguistic minority students to acquire academic literacy to become successful students in the university?

2. Do the students show differences among themselves in the speed and extent of academic literacy development? And if so, what factors are related to the differences?

This study focused on the development of writing skills because they are a key element of the academic literacy construct whose product can be objectively analyzed.

Also, it is through writing that post-secondary educators in a majority of disciplines evaluate students’ academic competencies.

Although this study focused on immigrant students in California in the United States, the findings are likely to be relevant for investigations into the educational needs of linguistic minority students who are increasing in number in nations across the world as globalization prompts the pace of transnational migration of peoples.7 The findings are also relevant for understanding the meaning and importance of the UNHCHR declaration on the rights of linguistic minorities and should serve as a caution of the grave consequences of making unsound language policy decisions.

The Nature of Academic Literacy

University educators in the United States claim that linguistic minority students are prevented from becoming successful students in the university because they lack academic literacy in English. However, academic literacy,8 a term generally accepted to represent the ability to read, write, and think critically, as a concept has been a subject of controversy since the 1980s as educators attempted to give it a more comprehensive definition to address the pedagogical needs of remedial students many of who are identified as ethnic and linguistic minority students.

To some researchers, academic literacy is not a universal construct but a socially derived one. For example, Hull et al. (1991) states that people’s perceptions and beliefs about literacy and learning, though tacit, are culturally biased; and the term remedial to depict students who do not command academic literacy is a social construct derived from a deficit model that assigns the source of academic failure to elements of the students’

status—their disadvantaged social background or cultural characteristics, if not their

cognitive deficiency (i.e., low intelligence).

Many studies support the hypothesis that academic literacy is socially constructed.

Some show that patterns of language socialization, language use, and display of literacy differ from culture to culture (Clancy, 1989; Heath, 1983, 1986; Scollon and Scollon, 1981;

Scollon, 1991). Others (Hillard, 1989; Harklau, 1994; Hull et al., 1991; Moll and Diaz, 1987) indicate that biased assumptions about languages and ethnic and linguistic minority students influence curriculum decisions and instructional practices that could, to use McDermott’s (1987) terminology, manufacture failure of these students. Hence, Hull et al.

(1991) conclude that culture based explanations of student inabilities to perform certain academic tasks are flawed, underscoring the observation that all humans engage in cognitive and linguistic processes to make meaning and that human beings are amazingly adaptable to new situations.9 This line of thinking suggests, then, that causes of academic deficiency have more to do with structures and practices of academic institutions rather than with the students themselves.

Setting aside the fundamental nature of academic literacy, public universities in California have defined academic literacy as intellectual and practical dispositions that promise academic success. Specific skills comprise three elements: (a) critical thinking skills that enable the student to question, analyze, synthesize, and evaluate ideas; (b) writing competencies that include the ability to write a clear thesis and identify, evaluate, and use evidence to support or challenge the thesis, and the ability to pay attention to diction, syntax and organization; and (c) reading competencies that include the ability to read for literal comprehension and retention, for depth of understanding, and for analysis and interaction with the text (Intersegmental Committee of the Academic Senate, 2002). Linguistic minority students in California post-secondary institutions have no choice but to acquire and demonstrate these skills in English since the state mandates an exit exam in academic literacy that all graduating students must pass.

Acquisition of L2 Academic Literacy

Much research into the acquisition of academic literacy for linguistic minority students has focused on elementary and secondary school learners. The research, however, is relevant for the present study because academic literacy education in the elementary and secondary school affects learning in the university.

A remarkable misconception is that the difficulty linguistic minority students have in acquiring academic literacy is a problem of linguistic mismatch. According to this

thinking, the difference between the students’ home language and the language of the school prevents students from “accessing” knowledge and skills needed to acquire academic literacy (for example, if an immigrant student’s home language is Spanish and the school language is English, the student will not be able to acquire academic literacy because he does not understand English). However, this notion is inconsistent with research findings into immersion programs that place students in content classes such as mathematics and language arts taught in the language that they do not know with the aim of achieving additive bilingualism.10 For instance, Swain (1979) found that English-speaking children in Canada who were immersed in French and taught a regular elementary school curriculum in French succeeded in acquiring not only grade level academic literacy but also proficiency in French. Similar findings have been documented by other research (Genesee, 1987;

Lambert & Tucker, 1972; Swain & Lapkin, 1982). These immersion program studies have led educators to conclude that language and academic content learning can be achieved simultaneously when language instruction is integrated with instruction in academic content (Genesee, 1985, 1987; Snow & Genesee1989). The finding has inspired universities with large populations of linguistic minority students to train content faculty to teach courses in ways that develop both the academic literacy and content knowledge of linguistic minority students.11 The finding has also made content-based instruction an au courant approach to teaching EFL.12

Although studies indicate the success of foreign-, second-language immersion education for some groups of students (for example, Canadian Anglophone students who speak the mainstream or dominant English language and are middle-class socioeconomically), such intense education has been less successful for linguistic minority students. A large-scale longitudinal study by Ramirez, et al. (1991) that analyzed the learning outcomes of more than 2000 linguistic minority students in the United States found that contrary to expectations, those who started English in early elementary school and had the most exposure to English eventually fell behind in English language achievement as well as in achievement in content areas and were deemed unlikely to catch up with native English speaking peers in academic achievement. On the other hand, the Ramirez study found that those who received some English language instruction but were taught in L1 for the longest period in the elementary school and had the least exposure to English did much better in later elementary grades. In fact, the late English learners were the ones who appeared to have the propensity to achieve native levels of English in later school days and show grade-level academic achievement as well. Similarly, other studies (Thomas and Collier, 2002) show the strongest predicator of L2 achievement is the amount of formal schooling

that students receive in respective L1. Moreover, many studies (Genesee, 1994; Fishman, 1976; Lambert, 1975; Ramirez, 1991; Swain, 1979) show that two-way bilingual education is superior to and has longer time benefits than mainstreaming approaches that attempt to expose students to maximum amount of time in the new language.

In sum, research indicates that sustained bilingual instruction of several years in both LI and L2 languages ensures that academic literacy skills that have been shown to take several years to develop (Collier, 1987, 1989; Cummins, 1981; Wong-Fillmore, 1991) can be adequately developed to establish a viable foundation for long-term growth of academic literacy. Therefore, many educators and researchers claim that California’s failure to develop the academic literacy of linguistic minority students has more to do with to do with misguided policy decisions that heeded largely to political elements than the findings of educational research.

Educators also point out that socio-cultural factors that determine policy decisions also influence educational practices within the school and affect the linguistic minority students negatively. For example, Cummins (1992) is critical of educational practices of a typical American classroom where “the vision of our future society implied by the dominant transmission models of pedagogy is a society of compliant consumers who passively accept rather than critically analyze the forces that impinge on their lives” (p.66). Thus, he quotes Sirotnik (1983) to indicate that a hidden curriculum is being communicated to students in a typical American classroom:

A lot of teacher talk and a lot of student listening... almost invariably closed and factual questions... and predominantly total class instructional configurations around traditional activities — all in a virtually affectless environment. It is but a short inferential leap to suggest that we are implicitly teaching dependence upon authority, linear thinking, social apathy, passive involvement, and hands-off learning (p.100).

Cummins states that for linguistic minority students, this results in “a reproduction of the conditions of social injustice that characterized their parents’ and grandparents’ relationships with the dominant group” (100). Hence, a study of the academic literacy development of linguistic minority students must take into consideration, the classroom and the larger socio-cultural context in which the students were educated.

This Study

This study is a case study conducted using data obtained by a large scale

university funded study conducted in the early 2000’s whose goal was to make policy as well as curriculum and instructional recommendations that will not only address the needs of linguistic minority students but also forge a multicultural and multilingual society that car reap the benefits of cultural and linguistic diversity. The findings of the large scale study have been reported in academic conferences in the state of California and have been used in the California State University System as an internal document to inform its academic senate. This study that profiled individual students, was conducted by this researcher to not only find answers to the research questions stated above but also to capture the human dimension of the issues surrounding the education of linguistic minority students.

Participants

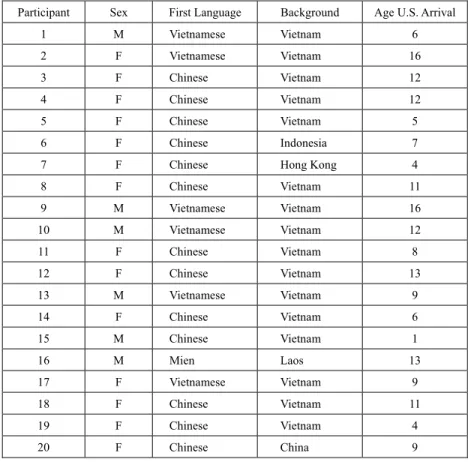

The participants of the study were 20 first year students enrolled in a one-year developmental English course in an urban California university.13 Six were male and 14 were female students. All were Asian immigrants14 although the ages at which they arrived in the United States differed (Table 1). None were enrolled in bilingual programs that maintain and develop the mother tongue. Instead, they were mainstreamed in English-only classes as soon as they began school in California. All reported that English was not their first language (L1) and were admitted into the university under its admission policy that gives educational opportunities to students who come from underprivileged backgrounds. They were designated as English Learners (EL) and were required to take non-credit bearing remedial English courses before they could take the for-credit required English courses.

In accordance with the university’s guidelines for the Protection of Human Participants, their identities were protected by assignment of pseudonyms and they were given the option to decline from participating in the study. While the participants self-selected themselves to take part in the study, they are representative of the population of Asian immigrants to California. Historically, Asian immigrants to the United States have been accorded lower socio-economic status that most often translates to receiving education in under-funded schools with little resource to support their needs.

Table 1 Background of the Participants

Participant Sex First Language Background Age U.S. Arrival

1 M Vietnamese Vietnam 6

2 F Vietnamese Vietnam 16

3 F Chinese Vietnam 12

4 F Chinese Vietnam 12

5 F Chinese Vietnam 5

6 F Chinese Indonesia 7

7 F Chinese Hong Kong 4

8 F Chinese Vietnam 11

9 M Vietnamese Vietnam 16

10 M Vietnamese Vietnam 12

11 F Chinese Vietnam 8

12 F Chinese Vietnam 13

13 M Vietnamese Vietnam 9

14 F Chinese Vietnam 6

15 M Chinese Vietnam 1

16 M Mien Laos 13

17 F Vietnamese Vietnam 9

18 F Chinese Vietnam 11

19 F Chinese Vietnam 4

20 F Chinese China 9

Methods and Data Collection

Two one-on-one interviews lasting approximately 1 hour each were conducted for each of the participants with a six-week interval. The first set of interviews gathered information about the participants’ backgrounds, while the second clarified and verified information gathered earlier. Table 2 shows sample interview questions.

Table 2 Sample Interview Questions

• What is the first language you learned to speak? Is this your mother’s native language? Your father’s?

• What language(s) do you currently use to communicate with family members? With friends?

• What is the highest level of formal education you attained in your first language?

• How often do you read in your native language? If so, what kind of things do you read?

• How often do you write in your native language? If so, what kind things do you write and to whom?

• How much opportunity did you have to learn English as a second language in your K-12 education?

What kind of instruction did you receive?

All the interviews were tape-recorded and later transcribed.

In order to trace the developmental path of the participants’ writing, their end-of- course portfolios for three consecutive terms were collected. The portfolios included reflective journal entries, various types of essays from the first draft to the final draft, in-class writing, and reflective portfolio introductions. The portfolios were read and evaluated holistically by two researchers who were qualified English instructors using a protocol that evaluated six areas of writing: topic development, organization, connections, sentence structure, vocabulary, and mechanics. I analyzed the interview data inductively and recursively throughout the project together with the participants’ writing skills data derived from their portfolios in order to arrive at a comprehensive profile for each participant.

Findings

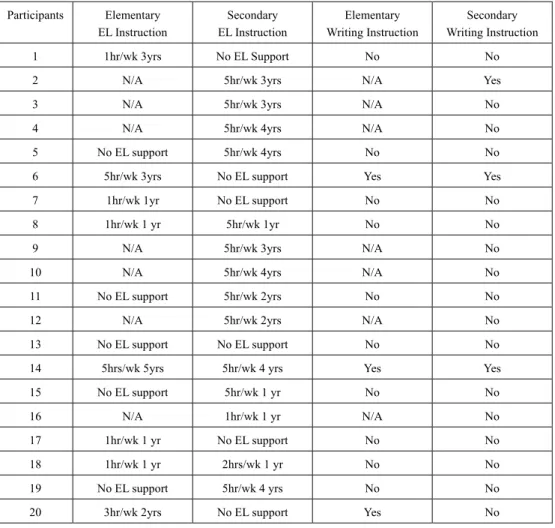

As shown in Table 3, a majority of the participants reported that they did not receive adequate support for English language (EL) development in elementary school: Of the 14 participants who began U.S. education in elementary school, 5 received no EL instruction though they spoke no English at matriculation. Another 5 received 1 hour of EL instruction per week for 1 or 2 years. Only 3 participants received up to 5 hours of instruction per week for 1 or 2 years. Access to EL instruction was slightly better for the participants during middle and high school: A total of 8 participants received 5 hours of EL instruction per week for 3 to 4 years, and 4 received 5 hours of EL instruction for 1 or 2 years. Among the remaining participants, 2 received 2 hours a week for 1 year and 1 hour a week for 1 year respectively. However, 6 participants received no EL instruction throughout middle and high school. It is noted that 4 participants who received no EL instruction in the elementary also received little or no EL instruction in the subsequent school years. In sum, the amount and duration of EL instruction participants received varied considerably with a significant number of participants receiving almost no EL instruction during elementary and secondary schooling.

The interview data also shows that the type of EL instruction the participants received varied considerably with a majority of participants responding that in elementary school, most instruction focused on listening and speaking and even in the middle and high school, reading and writing instruction constituted less than a third of instructional time.

Writing instruction, according to the participants, focused on writing sentences and short paragraphs, doing grammar exercises, answering comprehension questions in reading

workbooks, and practicing vocabulary and spelling. None of the participants reported receiving the type of writing assignments that their university instructors later assigned.

When the participants were asked whether or not they received feedback on written work that helped acquisition of English skills, only 2 out of 14 who attended elementary schools in the U.S. responded positively. Others from this group responded that they did not do much writing in elementary school. In middle and high school, only 3 out of 20 participants responded that they had regular writing assignments such as writing journals or essays on personal experiences and were given helpful feedback on written work.

Feedback, according to the participants, largely concerned grammar and composition length.

Table 3 Amount of EL instruction and Writing Support Participants Received in K-12 School Participants Elementary

EL Instruction

Secondary EL Instruction

Elementary Writing Instruction

Secondary Writing Instruction

1 1hr/wk 3yrs No EL Support No No

2 N/A 5hr/wk 3yrs N/A Yes

3 N/A 5hr/wk 3yrs N/A No

4 N/A 5hr/wk 4yrs N/A No

5 No EL support 5hr/wk 4yrs No No

6 5hr/wk 3yrs No EL support Yes Yes

7 1hr/wk 1yr No EL support No No

8 1hr/wk 1 yr 5hr/wk 1yr No No

9 N/A 5hr/wk 3yrs N/A No

10 N/A 5hr/wk 4yrs N/A No

11 No EL support 5hr/wk 2yrs No No

12 N/A 5hr/wk 2yrs N/A No

13 No EL support No EL support No No 14 5hrs/wk 5yrs 5hr/wk 4 yrs Yes Yes

15 No EL support 5hr/wk 1 yr No No

16 N/A 1hr/wk 1 yr N/A No

17 1hr/wk 1 yr No EL support No No

18 1hr/wk 1 yr 2hrs/wk 1 yr No No

19 No EL support 5hr/wk 4 yrs No No

20 3hr/wk 2yrs No EL support Yes No

Asked about their earliest experiences in U.S. schools, all participants reported difficulties in social as well as academic aspects of school life. For many, the initial school experience was sink or swim: They received little academic support from the school.

Furthermore, nearly all participants reported feeling alienated and experiencing a range of adjustment problems, and that no help was given at school to overcome such difficulties.

One participant expresses the collective experience:

I felt lost and lonely in school. Before I got accepted in that school, I had to take a math and English test. Just by looking at the sign on the math exam, I could tell what they want me to do.

However, on the English test, I just knew to draw the black bubbles on the answer sheet without understanding anything. As I finished the exam, my cousin took me to my counselor and he left me there. Suddenly, I felt lost. I was like a little girl who was in a strange crowded place.

I just wanted to go home with him or I might beg him to stay with me a little longer. My first class was math course. I sat in the classroom without knowing what was going on around me.

Even my teacher asked me how I was, I just stared at him and shook my head. People looked at me with hostilities just like I was a stupid person. I was not able to speak a word. I was really afraid when the teacher looked at me because that meant he might ask me something.

There were some Vietnamese students in class, but they didn’t want to talk or make friends with me because I didn’t know how to speak English; I didn’t have nice clothes either. Furthermore, I was in Vietnam way and they were in American style. Making friend with me seemed a shame to them. The bell rang. The students were dismissed from their classes. They were out like a big wave from the ocean. They joined happily together. They all went to lunch. I stood lonely in a corner seeing people passing by me. After school while waiting for someone to pick me up, I walked up and asked a Vietnamese girl how to apply for the school lunch program. She gave me an unfriendly look and shook her head. One week later in school cafeteria, I stood in line to get food, and that girl was behind me, speaking fluently in both

Vietnamese and English.15 (Ming’s journal)

Looking at writing skills development, this study shows that only 3 out of 20 participants, with teacher feedback on writing in earlier drafts, were able to produce essays whose content and convention meet the standard to exit the developmental English program at the end of its one year duration. All of these students were those who reported receiving EL instruction and feedback on their writing. They were also the ones who reported literacy in L1.

In contrast, the writing of 6 participants failed to reach the standard during the one-year developmental writing program. Worse, their writing showed little development

despite teacher feedback and concentrated support from the instructor through writing conferences. These were the participants who received little or no EL instruction or writing instruction throughout their K-12 schooling. What marks them is that although they can express ideas in English, both their spoken and written language form is far from acceptable as sampled:

All my life, I influence by my friends are in gangs. They influence me into smoke, cut classes, and getting into fights. When I just moved to California, I met a guy in Elementary School who I thought he was not a troublemaker. So we become best friends. From that day on, we gone through a lot together.

What additionally marks them is that repeated instruction on language forms, both oral and written, and increased spoken and written English language input did not appear to improve their speaking or writing.

Finally, while the other 11 participants showed varying degrees of writing skills development during the one-year period, none met the standard to enroll in freshman composition.

To conclude, the findings indicate that by far, the participants’ educational background during their K-12 education and literacy in L1 appear to be key factors affecting the writing skills development of linguistic minority students. Participants who received adequate L1 literacy education before entering the United States made remarkable development in L2 writing skills. Participants not literate in L1 and who did not receive EL instruction during K-12 did not respond well to instruction; it was as if their L2 has fossilized. Most importantly, the assumption that a one-year developmental English program could bring students lacking in EL competency and educational experiences that facilitate academic literacy up to par with other students is not supported by the findings of this study.

Participant Profiles

By focusing on the profiles of two participants, an achiever and a non-achiever in the developmental writing program, I hope to provide a glimpse of the emerging patterns of differences in writing development among linguistic minority students enrolled in universities in California.

Profile of an Achiever

Ming is a Vietnamese student who came to the United States from Vietnam at age 16. She attended Grades K through 8 in Vietnam and Grades 9 through 12 in California. She is literate in Vietnamese and continues to spend considerable time speaking, reading and writing in Vietnamese. She received EL instruction in high school which included writing instruction even though she claims that the instruction was not enough to make her confident or competent in university academic English. The reviewer of her first portfolio notes:

Ming has a general idea of the structure of an essay and knows the concept of a theme or thesis.

However, her essays stray from the topic and some of the content paragraphs are out of balance with others. Ming struggles to frame her topic and provide a tangible focus for the reader.

Her writing contains typical EL errors in the areas of sentence structure, verb tense, verb form, and omission of necessary words.

This observation is illustrated in her sample first paragraph of an essay on remediation:

The newspaper article “School Plan for Remedial Cuts” by Robert Haggard is published. In this article Robert Haggard is going to tell us about this educational plan, why the government is wanting to do that, how it’s going to effect if this proposed policy will be passed. After I finish reading, I disagree with this plan.

Three months later, the reviewer comments:

In the second portfolio, Ming showed progress in all areas evaluated—topic development, organization, connections, sentence structure, vocabulary, and mechanics. Though a moderate amount of errors still appear in her writing, she responded well to the feedback of her teacher.

Ming was also experimenting, often successfully, with complex grammatical structures and new vocabulary.

Toward the end of the year, the reviewer states:

In the third portfolio, Ming continues her steady progress toward academic literacy. This progress is apparent in all six-skill areas represented. Not only is Ming mastering the mechanics of writing, but also a distinct voice is emerging with an almost poetic quality.

Though by no means perfect, her writing is clearly approaching a level acceptable in the American university.

Below is a sample paragraph on the topic “The Little Mermaid:”

The blind love and the desires had motivated her to forget all her precious possessions, even her parents. She gives up her life in the ocean, her beautiful tail, and her lovely sweet voice to be like a human being, and to be with a prince. However, every step that she walked on, it would be like a sharp sword piercing her. Furthermore, if she failed to win the prince’s love, she would not obtain an immortal soul. She would become mere foam.

Profile of an Under-Achiever

Mark is a Mien student who was born in Laos and came to the United States through Thailand at age 13. He received sporadic education in refugee camps and in Thailand during Grades K through 5, and attended Grades 9 through 12 in California. He reports that his L1 is Mien, L2 is Thai, and L3 is English but that he can only read and write in English. He received very little EL instruction in high school and claims he is completely incompetent in university academic English. The portfolio reviewer notes:

In his first portfolio, Mark demonstrates a lack of understanding of the function of paragraphs and essays. He adheres to simple syntactical structures and his writing lacks transitions and connectivity. At the sentence level, there are frequent structural and grammatical errors. His responses to feedback from the teacher do not always improve the essay.

Below is Mark’s sample paragraph:

The story of “mice and men” written by John Steinbeck was about two men who traveled around to seek for job to make their life better in living. George was a small short, and smart man.

Lennie was a big tall strong man, but he was mentally retarded. Lennie was a person who liked to touch something that is soft. Rabbits were animals that Lennie was very crazy of getting it.

Later, the reviewer notes:

In Mark’s second portfolio, there was no observable progress in five of the six skill areas evaluated. The exception was minor gains recorded in the area of connectivity. Essays in Portfolio 2 are virtually indistinguishable from essays in Portfolio 1.

And finally, the reviewer comments:

In his third portfolio, Mark has begun to experiment with complex structures in his writing, Nonetheless, the third portfolio essays still do not differ significantly from the first portfolio essays. In at least one of the grammatical areas assessed, Mark appears to have lost ground.

Finally, most importantly, he has clearly not achieved academic literacy.

Below is Mark’s sample paragraph:

In the story Tito’s Good-Bye by Cristina Garcia was about a man who died with the regret, but eventually he didn’t even bet to be regret because of all the sudden when he died. Tito who worked as a lawyer for the poorest immigrants in New York City. Those immigrants were uneducated men and women so then Tito impressed then with smooth talk.

Conclusions

This study indicates that for a majority of the linguistic minority students, one year is inadequate to become competent writers and successful university students. The study supports the view held by language acquisition experts that students who are literate in L1 are more likely to become competent L2 writers in a shorter length of time than those who are not. Hence, as contended by supporters of bilingual education, linguistic minority students will most likely benefit from two-way bilingual education programs that foster L1 maintenance and development while working on the students’ acquisition of English as a second language. On the other hand, when students’ L1 is not allowed to develop into L1 literacy and at the same time, they are not given adequate and timely EL instruction, their chances of compensating for this lack appear to diminish, pointing to the likelihood of the existence of a critical period in academic literacy development.

As this study shows, linguistic minority students arrive on the university campus with a wide range of backgrounds and educational experiences that are clearly reflected in an equally wide range of differences in the speed and extent of their writing skills development. Hence, the one-size-fits-all approach is unlikely to raise skills to faculty expectations. Instead, universities should categorize students more thoroughly by using language dominance and language literacy as criteria. For example, students who are L1-dominant but not literate are unlikely to benefit from the same instruction as students who are both dominant and literate in L1. Likewise, students who are nearly bilingual and have been educated primarily in the United States may be better off in native speaker classes instead of being placed in EL classes.

As for students who were denied access to adequate and appropriate educational experience for an extended period of time, an entirely different type of instruction is in order.

For them, instruction must provide enriching language experiences—those that give them ample opportunities to interact and read and write in English, and receive constructive feedback on their output, both spoken and written.

Finally, this study points to a larger issue that intersects language and society.

Although most immigrant students desire to become successful adults in their new homes, they nevertheless feel a great social distance between themselves and the mainstream society. They are also often ambivalent about people outside their ethnic groups. The participants of this study reveal their struggles to overcome isolation while attempting to maintaining their fragile identity and about prejudices they must bear while facing pressures to conform to societal norms. Thus, one participant writes:

I not good with English. I come to America to study because in my country United States is the best in everything. Since I am here, I sad to find it untrue. Many things are good, but I find many teachers who want me to be like American student. I cannot and not want to be someone different. I just want respect like American students has. (From Vi’s journal)

Social distance between linguistic minorities and the society at large, whether real or perceived, does not bode well for communication and language learning. Therefore, while it is important for the newcomers to attempt to close that distance, individuals in the mainstream, including educators, must adjust their attitudes and behaviors toward them and cultivate a more ethnically integrated society that appreciates cultural differences.

One of the most important insights gained form this study is that there are two sides to the equation when it comes to the education of students in secondary institutions.

Universities need to uphold and communicate their educational expectations to their constituents including elementary and secondary schools, current and future students, and their own faculty. At the same time, however, they must put into place mechanisms to analyze and understand their students and institute programs that can realistically enable students to succeed in meeting the expectations.

Finally, it is my hope that nations which intake immigrants embrace the educational policies recommended by the United Nations and protect the language rights of immigrant students. This will require the governments of monolingual countries like the United States and Japan to support the development of bilingual and multi-lingual education for not only the linguistic minorities but also for the majority in order to nurture the development of a truly multi-cultural, global society.

Notes

1 In 1986, Bilingual Education Act was passed in the United States to address the educational neglect and disadvantage of linguistic minority students although how to remedy the situation was left up to the school districts. Parents of linguistic minority students and communities often favored the enrichment model—the bilingual-bicultural education—designed to preserve fluency and literacy in both the native

language and English. However, some educators, policy makers, and critics of mother-tongue instruction have crafted state ballot initiatives that codify a preference for intensive English instruction.

Language policy is a contentious issue in the United States.

2 Note that some Japanese educators base their opposition to implementing English language education in the Japanese elementary schools on similar grounds.

3 In Article 4.3 the phrase whenever possible should be deleted to give more strength to the declaration.

4 CELDT is a test of English proficiency administered to students from grades K-12 in California whose home language is not English to determine their English proficiency level, and monitor progress toward acquiring English proficiency.

5 California also has the University of California and the California Community Colleges.

6 The term developmental is used here instead of a more common term remedial, which is gaining currency even in educational circles in Japan. The term remedial suggests that students did not adequately learn what was taught or accessible to them. In the case of linguistic minority students, lack of access to learning is an issue.

7 For example, Japan considers itself a monolingual nation. However, according to the Ministry of Justice 2.22 million foreign nationals were in Japan in 2008(Japan Times, 2010). This is a 46.6 percent increase from a decade ago. Also, according to the Tokyo metropolitan government, there were 22,314 linguistic minority students in public schools who needed Japanese language support in 2006. The Japanese government does not support the mother tongue maintenance of its language minority students.

8 A comprehensive definition of academic literacy also includes numerical, and information technology literacy. In Japan, academic literacy is commonly called アカデミック・スキル(=academic skill).

9 These observations have led Brodkey (1989) to suggests that the explanation for failure must be sought elsewhere—in social structures and inequity.

10 Additive bilingualism is the acquisition of a second language and the development of the first. It is distinguished from subtractive bilingualism where learning of the second language brings about an eventual weakening or loss of first language abilities.

11 Project LEAP (Learning-English-for-Academic-Purposes) by California State University Los Angeles was first started in 1996. More recently, in 2008, a new LEAP Project, Give Students a Compass: A Multi-State Partnership for College Learning, General Education, and Underserved Student Success, funded by Carnegie Corporation was initiated to focus on the educational needs of students who, historically, have been underserved in higher education: first generation students, ethnic and racial minorities, and those from low-income families. Faculty training is a part of this initiative.

12 It has also popularized an EFL approach called content-based instruction that attempts to teach content courses in the students’ foreign language with the dual goal of enhancing the foreign language proficiency and teaching students content knowledge.

13 Upon matriculation into the California State University, students who do not score adequately on the English Proficiency Test are required to take the “remedial” developmental English courses called the Intensive Language Experience for the duration of one year.

14 African American students, also considered in some academic circles to be linguistic minority students were excluded in this study because their linguistic needs are different from that of immigrant students.

Latino students were grossly underrepresented in the university in which the study was conducted.

Therefore, their participation could not be gained.

15 I have not edited the errors present in Ming’s journal to preserve her voice as an immigrant student.

References

Brodkey, L. (1989). Transvaluing Difference. College English, 51, 597-601.

California Department of Education. (2010). California English Language Development Test. Retrieved from http://celdt.cde.ca.gov/.

Chronicle of Higher Education (2010). Cal State to Require Remedial Courses Before Freshman Year.

Retrieved September 5, 2010 from http://chronicle.com/blogPost/Cal-State-to-Require-Remedial/21915/.

Clancy, P.M. (1986). The acquisition of communicative style in Japanese. In B.B. Schieffelin & E. Ochs.

(Eds.), Language socialization across cultures (pp. 213-250). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Collier, V. (1987). Age and rate of acquisition of second language for academic purposes. TESOL Quarterly, 21, 617-641.

Collier, V. (1989). How long? A synthesis of research on academic achievement in a second language.

TESOL Quarterly, 23, 509- 531.

Cummins, J. (1981a). The role of primary language development in promoting educational success for language minority students. In California State Department of Education (Ed.), Schooling and language minority students: A theoretical framework (pp.3-49). Los Angeles: California State University, Evaluation, Dissemination, and Assessment Center.

Cummins, J. (1981b). Age on arrival and immigrant second language learning in Canada: A reassessment.

Applied Linguistics, 2, 132-149.

Cummins, J. (1989). Empowering Minority Students. Sacramento: California Association for Bilingual Education.

Cummins, J. (1991). Interdependence of first- and second-language proficiency in bilingual children. In E.

Bialystok (Ed.) Language processing in bilingual children (pp.70-89). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cummins, J. (1992) Bilingual education and English immersion: The Ramírez Report in theoretical perspective. Bilingual Research Journal, 16, 91-104.

Fishman, J. (1976). Bilingual education: What and why? In J. Alatis andK. Twaddell (Eds.) English as a second language in bilingual education (pp. 263-271). Washington, D.C.: TESOL.

Genesee, F. (1985). Second language learning through immersion: A review of U.S. programs. Review of Educational Research, 55, 541- 561.

Genesee, F. (1994). Integrating language and content: Lessons from immersion. The National Center for Research on Cultural Diversity and Second Language Learning, Educational Practice Report 11: 1-15.

Grosjean, Francois. (1982). Life with two languages: An introduction to bilingualism. Cambridge, Mass:

Harvard University Press.

Harklau, L.A. (1994). ESL and mainstream classes: Contrasting second language learning contexts. TESOL Quarterly, 28, 2, 241-272.

Harklau, L. (2000). Representations of English language learners across educational settings. TESOL Quarterly, 34, 35-67.

Harklau, L., Losy, K. and Siegal, M. (Eds.). (1999). Generation 1.5 meets college composition: Issues in teaching of writing to U.S.-educated learners of English as a second language. Mahwah, N.J.: Erlbaum.

Heath, S.B. (1983). Ways with words: Language, life, and work in communities and classrooms. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Hillard, A.G. (1989). Teachers and cultural styles in a pluralistic society. NEA Today, 7, 65-69.

Hull, G., Rose, M., Fraser, K.L., and Castellano, M. (1991). Remediation as a social construct: Perspectives from an analysis of classroom discourse. College Composition and Communication, 42, 3, 299-327.

Intersegmental Committee of the Academic Senate (2002). Academic Literacy: A Statement of Competencies Expected of Students Entering California’s Public Colleges and Universities. Sacramento, CA.

Ito, M. (2010). U.N. rights rep has bone to pick. The Japan Times Online. Retrieved on September 2, 2010 from http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nn20100407f1.html.

Lambert, W. (1975). Culture and language as factors in learning and education. In A. Wolfgang (Ed.) Education of immigrant student (pp.55-83). Toronto: O.I.S.E.

Lambert, W. E. and Tucker, G. R. (1972). The bilingual education of children. The St. Lambert experiment.

Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

McDermott, R.P. (1987). The explanation of minority school failure, again. Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 18, 361-364.

Moll, L.C. and Diaz, S. (1987). Change as the goal of educational research. Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 18, 4, 300-311.

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. (1996-2007). Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities. Retrieved on September 10 from http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/minorities.htm.

Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe. (1996). The Hague Recommendation Regarding the Education Rights of National Minorities. Retrieved on September 5 from http://www.osce.org/hcnm/

documents.html?lsi=true&limit=10&grp=45.

Ramírez, J., Yuen, S., Ramey, D., and Pasta, D. (1991). Final Report: Longitudinal study of structured English immersion strategy, early exit and late-exit bilingual education programs for language minority children. (Vol. I) (Prepared for U.S. Department of Education). San Mateo, CA: Aguirre International.

No. 300-87-0156.

Ramírez, J., Pasta, D., Yuen, S., Ramey, D., and Billings, D. (1991). Final report: Longitudinal study of structured English immersion strategy, early-exit and late-exit bilingual education programs for language-minority children. (Vol. II) (Prepared for U.S. Department of Education). San Mateo, CA:

Aguirre International. No. 300-87-0156.

Scollon, R. (1991). Eight legs and one elbow: Stance and Structure in Chinese English Compositions. Paper presented at the International Reading Association Second North American Conference on Adult and Adolescent Literacy, Banff, Canada.

Scollon, R. and Scollon, S. (1981). Narrative, literacy, and face in interethnic communication. Norwood, NJ.

Ablex.

Sirotnik, K. (1983). What you see is what you get — consistency, persistency, and mediocrity in classrooms.

Harvard Educational Review, 53, 16-31.

Snow, M.A., Met, M., and Genesee, F. (1989). A conceptual framework for the integration of language and content in second/foreign language instruction. TESOL Quarterly, 23, 201-217.

Swain, M. 1979. Bilingual education: Research and its implications. In C.A. Yorio, K. Perkins & J. Schachter (Eds.) On TESOL ‘79: The learner in focus. Washington, D.C.: TESOL.

Swain, M. and S. Lapkin. 1991. Heritage language children in an English-French bilingual program.

Canadian Modern Language Review, 47:4, 635-641.

Thomas, W.P., and Collier, V.P. (2002). A national study of school effectiveness for language minority students’ long-term academic achievement. Santa Cruz, CA: Center for Research on Education, Diversity and Excellence, University of California Santa Cruz.

Tokyo Metropolitan Government. (2007). Gaikokujin no kodomoni taisuru kyoiku no jyujitsu ni kansuru yobousho [Request regarding the enhancement of education of foreign children]. Retrieved on September 7, 2010 from http://www.metro.tokyo.jp/INET/OSHIRASE/2007/11/20hbg200.htm.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2003). Education in a Multilingual World. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001297/129728e.pdf.

Wong Fillmore, L. 1991. Second-language learning in children: A model of language learning in social context. In E. Bialystok (Ed.) Language processing in bilingual children (pp.49-69). Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Zehr, M.A. (2010, December 28). Hakuta: Fear of bilingualism is a part of U.S. Culture. Education Week.

Retreieved on December 29, 2010 from http://blogs.edweek.org/eduweek/learning-the-language/2010/10.