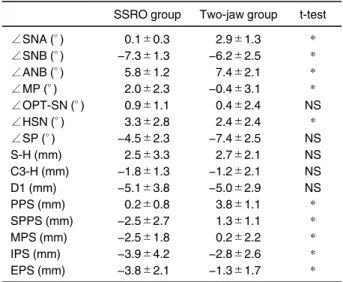

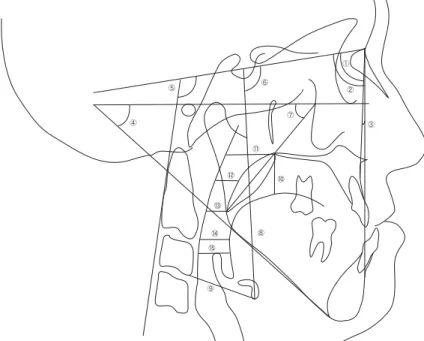

Influences of these procedures on the upper respiratory tract have also been widely studied.

全文

図

関連したドキュメント

Provided that the reduction of the time interval leads to incomparableness of normalized bubble-size distributions and does not change the comparable distributions in terms of

Asymptotic properties of solutions of homogeneous equations with constant coef- ficients and unbounded delays have been investigated also in [3]... The statement can be proved by

Eskandani, “Stability of a mixed additive and cubic functional equation in quasi- Banach spaces,” Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications, vol.. Eshaghi Gordji, “Stability

The purpose of this review article is to present some of the recent methods for providing such series in closed form with applications to: i the summation of Kapteyn series

This approach is not limited to classical solutions of the characteristic system of ordinary differential equations, but can be extended to more general solution concepts in ODE

As an application, we present in section 4 a new result of existence of periodic solutions to such FDI that is a continuation of our recent work on periodic solutions for

As a result, we are able to obtain the existence of nontrival solutions of the elliptic problem with the critical nonlinear term on an unbounded domain by getting rid of

Using a method developed by Ambrosetti et al [1, 2] we prove the existence of weak non trivial solutions to fourth-order elliptic equations with singularities and with critical