Gender differences in language use in Cebuano : an exploratory study

著者(英) Casilda E. Luzares journal or

publication title

Doshisha literature

number 40

page range 39‑54

year 1997‑03‑10

権利(英) English Literary Society of Doshisha University

URL http://doi.org/10.14988/pa.2017.0000014801

Gender Diffrences in Language Use in Cebuano:

An Exploratory Study

CASILDA E. LUZARES

INTRODUCTION1

Cebuano is a language spoken by the second largest number of speakers in the Philippines. It is geographically widespread, being spoken in several provinces in the Visayan islands (central Philippines) and in the big island ofMindanao (southern Philippines).

Gender differences in the linguistic system of Cebuano have not caught much interest among linguists, perhaps because Cebuanos (the people) intuit that there are none. However, the possibility that there might be differences in language use, especially in the choice of words or expressions, is not denied. It is not difficult to believe that women may prefer to use certain words or expressions and that men may prefer to use certain others, or that the vocabulary or expression system of Cebuano may communicate positive attitudes towards one sex and a negative attitude towards the other sex. For example, a few people have pointed out to me that Cebuanos say Maayong lalaki (ka)nang bayhana (literally 'That waman is a good man') to show admiration or perhaps envy for the subject's superior abilities, indicating that in the culture men, rather than women, are assumed to have superior abilities.

In the exploratory study reported here, I wanted to find out if there existed differences in the use of linguistic features of involvement (see Chafe 1982 and Hatch 1992): specifically, the use of details (including

[39J

what Tannen 1982 refers to as 'interpretive naming'), use of first and second person pronouns, and use of emphatic particles and intensifiers (what Hatch (1992) calls 'aggravated signals'). In addition, I examined how differently men and women structured discourse, and positioned themselves in relation to the task of communicating their experience (specifically the use of interpretation and evaluation and what Tannen 1982 refers to as 'interpretive naming') in the context of writing a letter to a friend in order to report an event that happened at work.

The subjects used in the study were 30 women and 27 men, graduate and undergraduate students in the 1992 summer program2 at the University of San Carlos in Cebu City. The women were all graduate students and most were already engaged in a profession. The men were mostly undergraduate students and only two were professionals. The average age of the women was 28.5 years while the men were very much younger - - 18.9 years on the average. Because of the small number of subjects and the difference in age and educational attainment, no sophisticated statistical tool could be applied. This study therefore should not be treated as anything but exploratory. Its value lies in the fact that it points to the possibility of the existence of important differences in language use between men and women.

The subjects were presented with a picture of people in an office who were all goofing during office hours (from Klippel 1984). The picture was chosen because of its 'reportability', i.e. the possibility that the subjects would consider the event serious or funny enough to report or share with a friend was high. Also, the situation depicted was not remote, i.e., it could happen in many offices in the Philippines. The subjects were asked to pretend they were one of the employees (see Appendix). They were

asked to write a letter to one of their friends telling what happened at the office one day the previous week. They were told to be as detailed as they could. Although the task was not timed, most finished within an hour.

RESULTS Length of Text

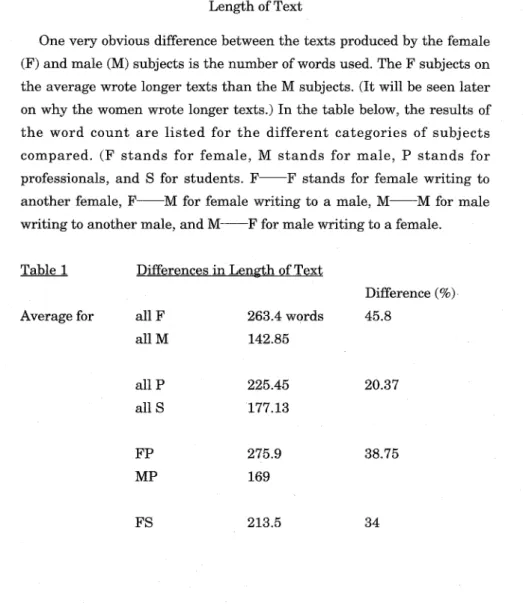

One very obvious difference between the texts produced by the female (F) and male (M) subjects is the number of words used. The F subjects on the average wrote longer texts than the M subjects. (It will be seen later on why the women wrote longer texts.) In the table below, the results of the word count are listed for the different categories of subjects compared. (F stands for female, M stands for male, P stands for professionals, and S for students. F--F stands for female writing to another female, F--M for female writing to a male, M--M for male writing to another male, and M--F for male writing to a female.

Table 1 Differences in Length of Text Average for all F 263.4 words

all M 142.85

all P 225.45

all S 177.13

FP 275.9

MP 169

FS 213.5

Difference (%) 45.8

20.37

38.75

34

MS 140.76

F - F 263.25 52.14

M-M 126

F - M 264.16 18

M - F 216.6

In addition to the differences indicated above, the comparisons also show the following results:

1. M--F texts were 41.79 % longer than M--M texts.

2. The length of F-written texts was not affected by sex of the recipient.

Structure of the Text

The letters produced by the subjects followed the conventional structure for this type of text. In the analysis of the structure of the text, I looked at the main part ofthe letter, that is what was included between the salutation and the complementary ending. (Some of the terms used in this section have been borrowed from Labov 1972 and Tannen 1980.)

The section that comes right after the salutation I call preliminaries.

Here, the writer (W) may include a greeting, make an inquiry about the reader's (R) health or situation or a wish for R's good health and happiness, and a statement about Ws general state or condition. W may also include statements related to a shared experience or knowledge (for example, thanking R for a card or a letter). Then W connects R to the

main point of the letter (in this case the report about what happened at the office the previous week), by either directly telling R that W would like to tell R about what happened, or, indirectly, by telling R about W's conditions at work in relation to the statement about W's general condition in the preliminaries section of the letter.

Then comes the narrative, which may be introduced by an abstract, or a summary of what happened (e.g. Gubot kaayo sa opisina niadtong usang semana. 'There was trouble at the office last week.'). The description of simultaneous actions (Labov's 'complicating action') follows, which is then followed by the climax (the arrival of the boss) and then the resolution (being reprimanded, fired, or given a warning). The coda concludes the report; here W brings R back to the present, for example, by telling R about how the event had affected W (e.g. Mao nang karon nagbinuotan na gyud ko. 'That's why now I have decided to be goodlbehave.').

The final section of the letter is the leavetaking. In addition to saying goodbye, W may include a hope that R was entertained by the letter, a request for a response, or an invitation for R to visit. Here, W may also extend greetings to members of R's family, or make a promise to visit R in the future.

Anywhere within the report, W may include interpretations, or statements or comments that provide background information or indicate W's attitude towards the subject or topic or situation being talked about.

These statements help R interpret the message being communicated by W, and include both elaboration (this will be explained in the next section) and evaluation.

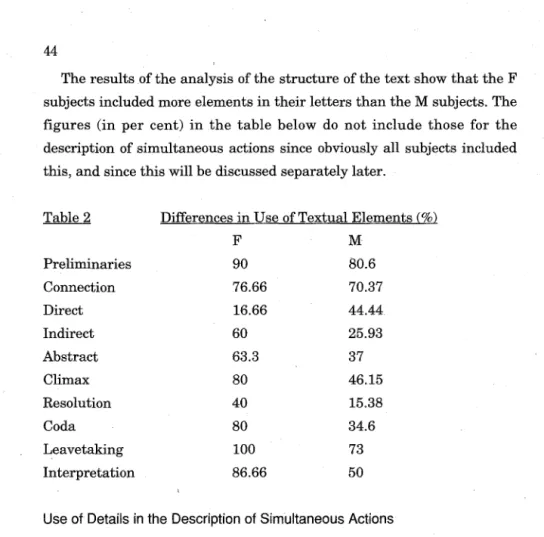

The results of the analysis of the structure of the text show that the F subjects included more elements in their letters than the M subjects. The figures (in per cent) in the table below do not include those for the description of simultaneous actions since obviously all subjects included this, and since this will be discussed separately later.

Table 2 Differences in Use of Textual Elements (%2

F M

Preliminaries 90 80.6

Connection 76.66 70.37

Direct 16.66 44.44

Indirect 60 25.93

Abstract 63.3 37

Climax 80 46.15

Resolution 40 15.38

Coda 80 34.6

Leavetaking 100 73

Interpretation 86.66 50

Use of Details in the Description of Simultaneous Actions

The subjects mentioned a total of 18 details and the highest number of details included was 15. The details are:

(1) two men playing cards and (2) betting;

(3) a woman reading a newspaper, (4) drinking coffee, (5) with her feet on the table;

(6) a woman reading a book, (7) drinking coffee, (8) eating a cookie, (9) an apple on her desk, (10) her telephone off the hook, (11)

her bags of groceries on the floor, and (12) her typing unfinished;

(13) a woman knitting (14) following a pattern;

(15) a man on top of a filing cabinet, (16) posting a caricature of the boss on the wall;

(17) a woman standing at the door, (18) holding a radio.

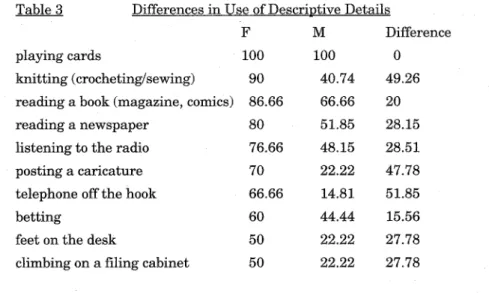

A count of the number of details included in the descriptions yielded the results shown in the table below. The figures indicate the percentage of subjects that included the particular detail and the percentage difference between the two groups of subjects. Only those details that were mentioned by at least 50% of either the F or M subjects are given.

Table 3 Differences in Use of Descril2tive Details

F M Difference

playing cards 100 100 0

knitting (crocheting/sewing) 90 40.74 49.26 reading a book (magazine, comics) 86.66 66.66 20

reading a newspaper 80 51.85 28.15

listening to the radio 76.66 48.15 28.51

posting a caricature 70 22.22 47.78

telephone off the hook 66.66 14.81 51.85

betting 60 44.44 15.56

feet on the desk 50 22.22 27.78

climbing on a filing cabinet 50 22.22 27.78

As shown above, 50% of the F subjects mentioned 10 details while the same percentage of M subjects mentioned only 3. The average number of details is 9.3 for the F-written descriptions and 5.26 for the M-written

descriptions. Of the 3 subjects who included 15 details, 2 were M and one was F; however, the M subjects had F as receivers.

In their description of simultaneous actions, certain features of involvement can already be seen. Eleven F subjects (or 36.66%) gave names to their co-employees (for a total of 47 names) while only 2 (or 7.4%) of the M subjects did (for a total of 6 names). In addition, 6 F subjects (or 23.33%) indicated the position of the employees or the division where they worked, compared with only one M subject (3.7%) who did so.

To get a closer look at how the subjects described the simultaneous actions, I decided to analyze the descriptions of two characters: the woman reading a newspaper (the character the F-subjects were asked to pretend they were) and the men playing cards (one of which was the character the M-subjects were asked to pretend they were). Here the F- subjects included a total of 124 information units, or an average of 4.13 for every description, while the M-subjects included a total of 56 information units, or an average of 2.6 units for every description. In the F-written texts, 19.35% of the information units were elaboration and 10.48% were evaluation. In the M-written texts, only 8.9% were elaboration and 5.36% were evaluation. The table below summarizes the differences:

Table 4 Differences in Types ofInformation Units Used

F M Diff(%)

Total no. information units 124 56 55

Basic info units (%) 70.17 85.74 15.57

Elaboration (%) Evaluation (%)

19.35 10.48

8.9 5.36

10.45 4.88 Use of Personal Pronouns and Direct Address

The F subjects used a total of 662 first and second person pronouns or an average of 22.07 for each text while the M subjects used 416 or an average of 15.41. The average for the first person pronouns is 16.43 for the F-written texts and 11.96 for the M-written texts. For the second person pronouns, the average is 5.63 for the F-written texts and 3.44 for the M-written texts. Sixteen F subjects, or 53.33% addressed R directly, by using either R's name or her nickname (e.g. Day, used by women with other women). Among the M subjects, 12 or 44.44% used the direct address. To summarize:

No. of Personal Pronouns Use of direct address (%)

F 662

53.33

M 416

44.44 Use of Emphatic Particles

Diff (%) 37

8.89

The emphatic particles included in the count are pa 'still, yet', ra 'only, solely', man 'yet, then', lang / lamang 'only, just', na 'already', gayud 'surely, indeed, certainly', bitaw 'indeed', lagi 'surely, indeed, as has already been said', diay 'it is so, indeed, then', baya (particle indicating assurance), andgani 'indeed'.

There is practically no difference between the proportion of emphatic particles to the total number of words in the F- and M-written texts. Of the total number of words used in the texts of the F subjects, 7.38% were emphatic particles; the figure for the M-written texts is 7.49%. Some

48

difference is seen when the subjects are broken down into the 4 categories according to the sex of R.

F - M M - F

9.71%

8.77%

F - F M-M

6.79%

6.59%

Use of Kaayu and Other Intensifiers

Cebuano speakers use intensifiers to emphasize magnitude, intensity, scale, etc. The most frequently used of these intensifiers is kaayu 'very', which is used to modify nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs. The other intensifiers are: pwerte, haska (hasta / asta), porbida, (hi)labihan, pastilan, bali, matay and super. Except for super, all are suffixed with the ligature -ng. When they are used to modify adjectives, the adjective takes on the suffix -a; thus, in it kaayu 'very hot' becomes pastilang inita.

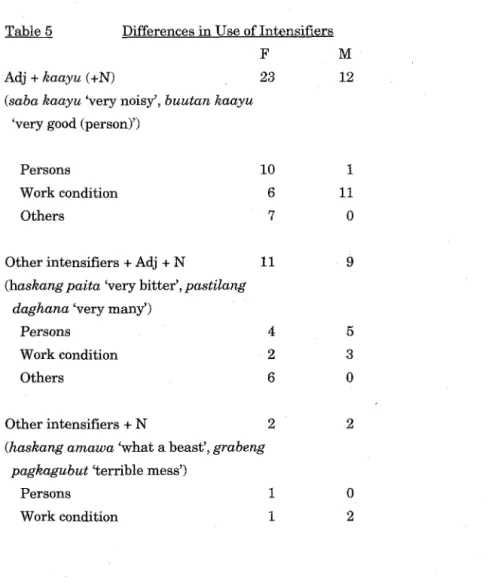

There were 76 occurrences of kaayu and other intensifiers in the F- written texts and 33 occurrences in the M-written texts. While 28 F subjects, or 93.33%, used them, only 21 M subjects, or 77.77% did so. The average number used in each text is 2.71 for the F-written texts and 1.57 for the M-written texts. In the F-written texts, there were 50 tokens and 6 types of structures while there were only 26 tokens and 4 types in the M-written texts. Also, a higher number of F subjects used verb-headed structures.

The use to which these structures are put also differs among the two groups of subjects. The M subjects used these structures to describe two things: the conditions at work, and people. In addition to these the F subjects also used these structures to describe other conditions (e.g. the weather) and objects. Of the two things described by the M subjects,

81.82% refer to work conditions and only 18.18% refer to people. On the other hand, among the noun-headed structures used by the F subjects, 43.58% refer to people, and only 23% refer to work conditions.

The table below gives the specific findings (number of tokens) related to the use of kaayu and other intensifiers:

Table 5 Differences in Use of Intensifiers Adj + kaayu (+N)

(saba kaayu 'very noisy', buutan kaayu 'very good (person)')

Persons Work condition Others

Other intensifiers + Adj + N

(haskang paita 'very bitter',pastilang daghana 'very many')

Persons Work condition Others

Other intensifiers + N

F 23

10 6 7

11

4 2 6 2 (haskang amawa 'what a beast', grabeng

pagkagubut 'terrible mess')

Persons 1

Work condition 1

M 12

1 11 0 9

5 3 0 2

0 2

50

Adv + kaayu + V

(sayu kaayu very early, dugay kaayu 'a very long time')

V +kaayu

(nahimuut kaayu 'was/were very pleased', enjoy kaayu 'enjoyed very much')

N +kaayu

2

o

8 3

3

o

(negosyante kaayu 'very much a business-minded person')

Discussion

In his article Integration and Involvement in Speaking, Writing and Oral Literature, Chafe (1982) presents some of the differences between spoken and written language. Some of these differences stem from the writer's or speaker's relationship with herlhis audience. Chafe claims that the speaker is more concerned with involvement than the writer:

... the speaker is aware of an obligation to communicate what he or she has in mind in a way that reflects the richness of his or her thoughts - - not to present a logically coherent but experientially stark skeleton, but to enrich it with the complex details of real experiences - - to have less concern for consistency than for experiential involvement ... I will speak of 'involvement' as typical for a speaker ... (p. 45) (Underlining provided for emphasis.)

The text used in this study is written language, but since it is the

language used in friendly letters, it shares many of the features of involvement of oral language that Chafe 1982 listed. That written language displays features characteristic of oral language was confirmed in a study which Tannen (1982) did on the oral and written versions of a story told by the same person. She found that although the written version displayed the features of 'integration' and 'detachment' (Chafe 1982), which are characteristic of written language, it also exhibited a number of the features of 'involvement' which characterize oral language.

In summary, the results indicate that the F-written texts displayed more features of involvement than the M-written texts. The analysis of the texts reveals that the F -writers:

1. included more details and elaborations,

2. Expressed their feelings and thoughts more (used interpretations and evaluations more),

3. used intensifiers more frequently and in greater variety to express enthusiastic involvement' (Chafe 1982:47),

4. used first and second person pronouns more frequently, and addressed their R's by name more frequently.

5. described people more frequently than work conditions.

6. told their stories more completely (i.e. used most of the elements of the narrative.)

There seems to be another factor at work to account for some of the differences, especially the difference reported as Result #6 above. The difference seems to result from a difference in task perception, i.e. the way the writers viewed the writing task. The F-subjects might have perceived their task as telling a story or sharing an experience and were therefore anticipating R's reaction (So what happened?). The M-subjects,

52

on the other hand, might have perceived their task as reporting on conditions at work rather than telling a story. If the former is the case, then, among the elements of a narrative, only the abstract and the description of simultaneous actions are necessary to accomplish the objective; the climax, the resolution and the coda are unnecessary. This would explain why the narratives of most of the M-subject would leave the reader's question "So what happened?" unanswered.

The results also show that a male writing to a female also adopts the same tendency towards involvement. This phenomenon may also be explained in this way: having perceived that the task was, in itself, an involvement-oriented task (producing what Tannen 1990 calls 'rapport- talk' rather than 'report-talk'), some M-subjects decided to write to friends who also already had this tendency, which means female friends.

This would support the assumption that men talk differently to men than to women, or that men present reality differently to men than to women.

Although the study presented here is only exploratory since the number of subjects is small, and the results very tentative because of the differences in age and educational level of the subjects, the findings seem to confirm the fact that men and women communicate differently or use language differently to communicate their experiences.

The study yielded interesting results; however all these will remain merely conjectures until statistically reliable results can be obtained.

Research in this area not only in Cebuano but also in the other Philippine languages obviousy need to be pursued.

REFERENCES

Chafe, Wall ace L. 1982. Integration and Involvement in Speaking, Writing and Oral Literature. In Tannen 1982.

Hatch, Evelyn. 1992. Discourse and Language Education. Cambridge University Press.

Klippel, Friederike. 1984. Keep Talking: Communicative Fluency Activities for Language Teaching. Cambridge University Press.

Labov, William. 1972. Language in the Inner City: Studies in the Black English Vernacular. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Tannen, Deborah. 1990. You Just Don't Understand. Ballantine Books.

- - - . 1982. The Oral/Literate Continuum in Discourse.

Spoken and Written Language: Exploring Orality and Literacy.

Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Notes

1 I would like to thank Dr. Ceferina Ranario of the University of San Carlos, for facilitating the gathering of the corpus for this study.

2 An earlier version of this paper was published in Japanese in the special volume Sekai No Josei-Go, Nihon No Josie-Go by Meiji Shoin in 1993.