Master’s Thesis

Toward a Comprehensive Analysis of

Asian Budget Destination Competitiveness and Backpackers:

Netnography and Autoethnography Approach

by PETER Ryan

51219006

March 2020

Master’s Thesis Presented to Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of International Cooperation Policy

i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ... i CERTIFICATION PAGE ... iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ... v ABSTRACT ... vi

LIST OF TABLES ... viii

LIST OF FIGURES ... ix

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ... x

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1. Background to the Research ... 1

1.2. Research Objectives ... 3

1.3. Research Questions ... 4

1.4. Significance of the Study ... 4

1.5. Thesis Outline ... 5

CHAPTER 2. LITERATURE REVIEW ... 6

2.1. The Evolution of Backpackers ... 6

2.2. Asian Backpackers ... 12

2.3. Destination Competitiveness ... 14

2.4. Synthesis and Proposed Model ... 18

2.5. Chapter Summary ... 31

CHAPTER 3. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY... 32

3.1. Research Paradigm ... 32

3.2. Approaches and Data Collection Methods ... 34

3.2.1. Grounded Theory ... 34

3.2.2. Netnography and Content Analysis on Online Forum ... 36

3.2.3. Autoethnography ... 40

ii

3.4. Reliability & Validity ... 45

3.5. Research Limitations ... 46 3.6. Chapter Summary ... 47 CHAPTER 4. FINDINGS ... 48 4.1. Affordability ... 49 4.2. Attraction ... 54 4.3. Accessibility ... 59 4.4. Amenities ... 66 4.5. Atmosphere ... 71 4.6. Amplifier ... 75 4.7. Chapter Summary ... 80 CHAPTER 5. DISCUSSION ... 81 5.1. Affordability ... 81 5.2. Attraction ... 86 5.3. Accessibility ... 91 5.4. Amenities ... 93 5.5. Atmosphere ... 98 5.6. Amplifier ... 102 5.7. Chapter Summary ... 105 CHAPTER 6. CONCLUSION ... 113

6.1. Response to Research Question 1 & 2: The Model of Budget Destination 113 6.2. Response to Research Question 3: The Asian Backpackers... 114

6.3. Theoretical Contribution ... 117

6.4. Practical Implication ... 126

6.5. Limitations and Future Directions ... 132

iii

REFERENCES ... 136

APPENDIX A. CTA: TOP 40 KEYWORDS ... 144

APPENDIX B. CTA: AFFORDABILITY ... 145

APPENDIX C. CTA: ATTRACTION (1) ... 146

APPENDIX D. CTA: ATTRACTION (2) & AMENITIES ... 147

APPENDIX E. CTA: ACCESSIBILITY ... 148

APPENDIX F. CTA: ATMOSPHERE & AMPLIFIER ... 149

iv

CERTIFICATION PAGE

I, Peter Ryan (Student ID 51219006) hereby declare that the contents of this Master’s Thesis / Research Report are original and true, and have not been submitted at any other

university or educational institution for the award of degree or diploma.

All the information derived from other published or unpublished sources has been cited and acknowledged appropriately.

PETER, Ryan 2019/11/05

v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Thanks must be expressed to my academic supervisor, Dr. Bui Thanh Huong. Her trust and intellectual guidance have contributed to the completion of this work timely.

Another gratitude is addressed to the Salesian Sisters (Figlie di Maria Ausiliatrice, FMA), who might have no idea that they’ve mentally supported this prodigal son throughout the hard times of settling down in the town after being a drifter for years. Their kindness truly represents the one, to whom I keep returning, for she is my spiritual home. In order to stop using awkward passive sentences in the first two paragraphs and create an ambiance of being mysterious and dramatic, please allow me to end it with one out of two favorite sayings of mine on this page. Sit finis libri, non finis quaerendi.

vi

ABSTRACT

Backpacking tourism is a global phenomenon. The growing popularity of backpacking tourism has attracted a lot of academic works written on this topic. Most of the works focus on the backpackers themselves, such as their motivations, behaviors, and impacts toward the destination. Meanwhile, there is only a few of literature discussing backpacking in the perspective of destination management, on what is perceived to be important and preferred by backpackers in the context of destination.

On the other hand, backpacking is used to be associated with Western travelers. Asia, particularly Southeast Asia is often regarded just as the ideal destination for backpackers. However, Asian backpackers are quite common to see nowadays, moreover around destinations in Asia. There is clearly a lack of discussions on backpacking tourism from the perspective of Asian travelers, creating a huge gap between the understanding of Western travelers in comparison to its Asian counterparts.

Those two points are the underlying background of this research, that has objectives to conceptualize a destination competitiveness model tailored specifically for backpacking tourism, while also identifying the differences between Asian and Western backpackers. In order to achieve them, this research employs the method of content analysis on the online forum of Lonely Planet’s Thorn Tree as well as participant observation through autoethnography for more than 3 years in the period of 2015-2019.

The study suggests that backpacker tourism has been mainstreamed, affirming that the previous generic destination competitiveness models might be applicable to the most extent in the context of backpacking tourism. However, there are some distinctive preferred attributes that uniquely attached to backpacking tourism, such as price-consciousness, work availability, tendency to do multiple visitations, need of common

vii

room and kitchen facilities in the budget accommodation, the opportunity to get getting immerse with the locals or subculture of backpackers, and so on. In addition, most of the Asian travelers also have some differences from its Western counterparts in terms of their attitude and preference, though not in every aspect. They might share many similarities, as backpacking tourism has been evolving and converging into a type of mass-tourism. The mainstreamization of backpacking tourism also brings some drawbacks to the host destination such as overtourism, whereas this research suggests some countermeasures to deal with it.

In practical realm, this study also provides some insights on assessing and improving the competitiveness of a backpacking destination. This is done through the conceptualization of a model named ‘6As of Budget Travel’ or simply the ‘Backpack Model’ which arguably can be used as a practical framework to analyze the competitiveness of a place as a backpacker or budget destination.

Keyword: Asia, backpacking tourism, backpacker, destination competitiveness, budget

viii

LIST OF TABLES

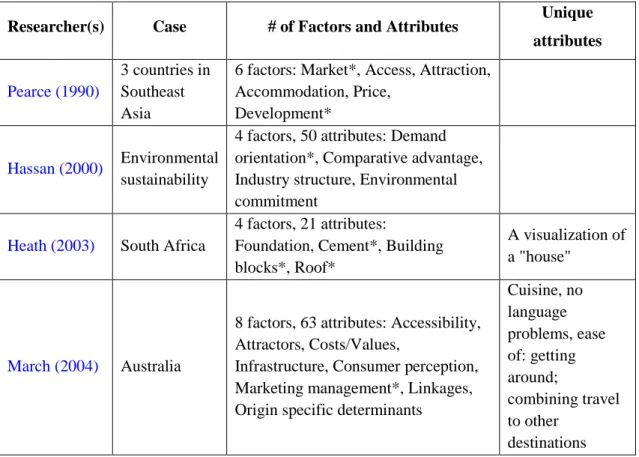

Table 2. 1. Destination Competitiveness Model from Previous Works ... 17

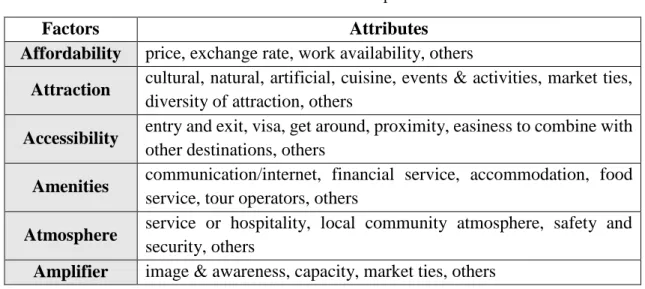

Table 2. 2. The Proposed 6As of Budget Travel ... 22

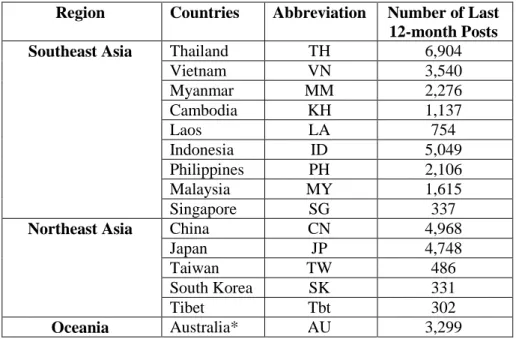

Table 3. 1. Samples of CTA (Netnography on Lonely Planet’s Thorn Tree) ... 39

Table 3. 2. Phases of Analyses ... 43

Table 4. 1. Findings on The Factor ‘Affordability’ ... 49

Table 4. 2. Findings on The Factor ‘Attraction’ ... 54

Table 4. 3. Findings on The Factor ‘Accessibility’ ... 59

Table 4. 4. Findings on The Factor ‘Amenities’ ... 67

Table 4. 5. Findings on Atmosphere ... 72

Table 4. 6. Findings on the Factor Amplifier ... 75

Table 5. 1. Treatment on Each Attribute Based on Its Significance ... 106

Table 5. 2. Summary of Comparisons between CTA and Autoethnography ... 109

Table 6. 1. Finalized Factors and Attributes of the '6As of Budget Travel' ... 114

Table 6. 2. Reflection on How Each Factor Improves Destination Competitiveness .. 129

ix

LIST OF FIGURES

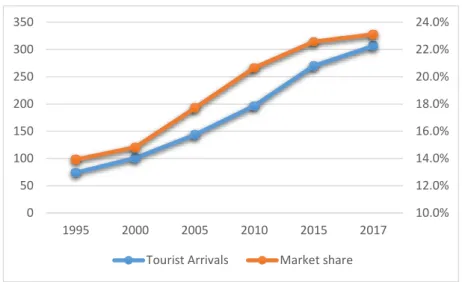

Figure 1. 1. Tourist Arrivals & Relative Market Share of Asia) ... 2

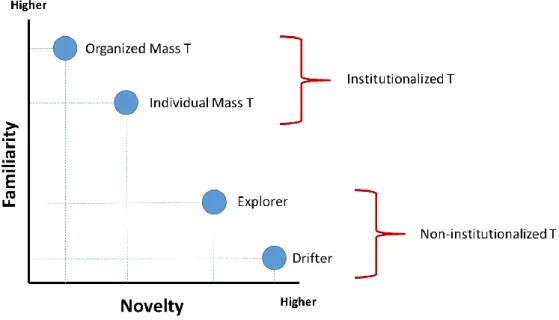

Figure 2. 1. Cohen's (1972) Typology of Tourists ... 7

Figure 2. 2. Cohen's (1973) Typology of “The Drifter” ... 11

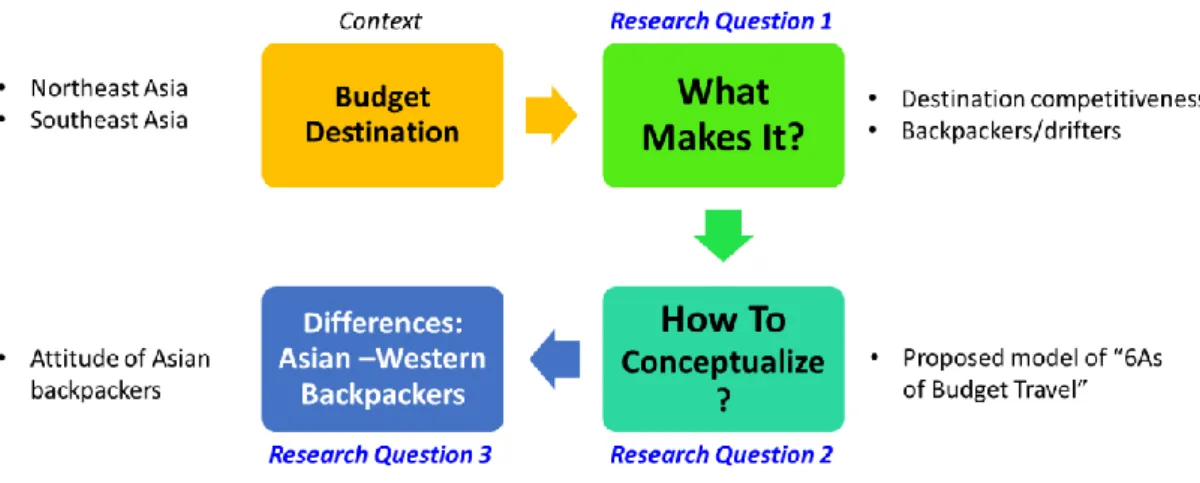

Figure 2. 3. How Synthesis on Literature Review Addresses Research Questions ... 31

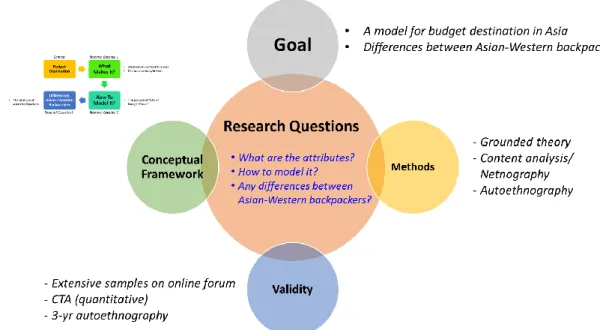

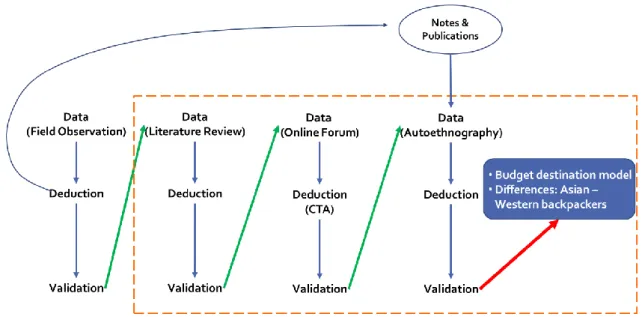

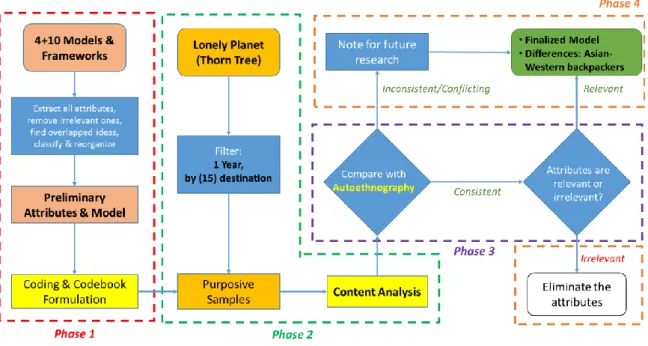

Figure 3. 1. Research Design ... 33

Figure 3. 2. The Ground Theory Method Used in This Research ... 36

Figure 3. 3. Analytical Framework ... 44

Figure 4. 1. How the Backpackers Perceive ‘Price’ and ‘Work’ While Travelling...54

Figure 4. 2. The Relationship Between Attributes in Attraction...58

Figure 4. 3. The Relationship Between Attributes in Accessibility...66

Figure 4. 4. The Relationship Between Attributes in Amenities...71

Figure 4. 5. Scope of the Attributes of Atmosphere...74

Figure 4. 6. The Relationship Between Attributes and Factors in Amplifier 80 Figure 5. 1. The Comparison of “Individualism” & “Uncertainty Avoidance” ... 85

Figure 5. 2. The Relationship Between Factors and Attributes ... 108

Figure 6. 1. Simplified Visualization: ‘The Backpack Model’ ... 118

Figure 6. 2. The Evolution of Backpacking Tourism ... 124

Figure 6. 3. Speculative Typology of Backpackers According to Their Sought Attribute ... 125

Figure 6. 4. Recommended Classification for Future Researches ... 133

x

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

AFF Affordability ACC Accessibility AME Amenities AMP Amplifier ATM Atmosphere ATT Attraction AU Australia CN ChinaCTA Content Analysis

GTM Grounded Theory Method

ID Indonesia JP Japan KH Khmer/Cambodia LA Laos MM Myanmar MY Malaysia PH Philippines SG Singapore SK South Korea Tbt Tibet TW Taiwan

UNWTO World Tourism Organization

1

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background to the Research

Youth travel is regarded as “the future of travel” which represents a major opportunity in the travel industry (UNWTO, 2011). According to UNWTO (2016), around 23% of global travel represents youth travel in 2015. Moreover, it is forecasted to reach 370 million international youth trips per year by 2020, almost doubling from 190 million in less than a decade. Among the subsectors of youth travel, this research takes backpacking tourism as its focus. Backpacking tourism or some might refer to it as budget travel is the subsector of youth travel (Locker-Murphy & Pearce, 1995; Richards & King, 2003; Richards & Wilson, 2005) which enjoys its rapidly growing popularity. Nowadays, backpackers can be found in every corner of the globe (Richards, 2015).

Destination-wise, the growth of tourist arrivals in Asia is tremendously impressive. The region has attracted more than 300 million tourists in 2017, quadrupling from 74 million tourists back in 1995. This increase remarks Asia as the fastest-growing region, with an average annual growth of 6.4% from 2005. This also results in a higher portion of market share, in which Asia is now comprising around 23% of the world’s market comparing to 13.9% in 1995, only second to Europe whose portion constantly declining as shown in Figure 1.1 (UNWTO, 2018). Moreover, Asia itself is closely associated to backpacking destinations, especially the classic trail around Southeast Asia (Hampton, 1998; Hampton & Hamzah, 2010; Muzaini, 2006; Spreitzhofer, 1998, 2002). However, while Asia in general is a popular travel destination region among budget travelers, there has been very little attention paid to systematically and comparatively analyze popular budget destinations in the region.

2

Figure 1. 1. Tourist Arrivals & Relative Market Share of Asia) Source: Researcher’s interpretation based on data of UNWTO (2018)

To date, there is a proliferation of works related to the phenomenon of budget travelers. However, the researcher identified at least three existing gaps which demand further analysis.

Firstly, majority of the work focuses on travelers’ demography and historical-sociological root (Cohen, 1972; 1979; 1984), intrinsic personal values and activities (Paris, 2010; Paris & Teye, 2010), behavior and travel strategy (Muzaini, 2006), and the impacts toward the host destinations (Hampton, 1998; Hannam & Ateljevic, 2007; Hannam & Diekmann, 2010; Ooi & Laing, 2010; Richards & Wilson, 2004; Scheyvens, 2002; Scheyvens & Momsen, 2008). But there is rarely, if any, a comprehensive work in seeing backpacking destination in the context of competitiveness model.

Secondly, despite of numerous research on place destination competitiveness, majority of the works are either on generic model (Buhalis, 1999; Crouch & Ritchie, 1999; Crouch, 2011; Dwyer & Kim, 2003; World Economic Forum, 2017; Gooroochurn & Sugiyarto, 2005;) or tailored for specific cases or destinations for mainstream tourists such as Southeast Asia (Pearce, 1997), Australia (March, 2004), South Africa (Heath,

10.0% 12.0% 14.0% 16.0% 18.0% 20.0% 22.0% 24.0% 0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2017

3

2003), Turkey (Kozak et al., 2003), MICE in the US (Chacko and Fenich, 2000), national park (Said & Maryono, 2018), religious tourism in Malaysia (Battour et al., 2011), hot springs in Taiwan (Lee & King, 2006), urban tourism in Hong Kong (Enright & Newton, 2004), city tourism in Lithuania (Cibinskienea & Snieskieneb, 2015), environmental sustainability (Hassan, 2000), and more.

Thirdly, most of the works focus on the perspective of Western backpackers while taking Asia only as destinations (Teo & Leong, 2006), meanwhile it is clear that the Asian travelers in general and Asian backpackers in particular are increasing either domestically or internationally (Chang, 2015; Cohen, 2003; Cohen & Cohen, 2015) – and it is even more significant in the case of Asians visiting Asian destinations (Muzaini, 2006). Meanwhile there are suggestions for future directions by many scholars, that there could be potential insights lie in the topic of differences between Western and Asian travelers (Bui et al., 2014; Chang, 2015; Cohen, 2003; Cohen & Cohen, 2015; Huang, 2008).

The three gaps identified justify why and how this research is therefore timely and necessary. This research is relevant in providing a contribution to narrow the gaps both theoretically and practically. Its ultimate objectives intend to answer the first and second gap, by attempting to conceptualize the destination competitiveness model in Asia, which taking context in Southeast and Northeast Asian destinations in this research, as well as to identify the differences between Asian and Western backpackers as a response to the third gap.

1.2. Research Objectives

4

a. To identify the attributes of what makes a budget destination in Southeast and Northeast Asia;

b. To conceptualize a model for budget destination competitiveness based on the aforementioned objective;

c. To identify the different attitudes between Asian and Western backpackers.

1.3. Research Questions

Therefore, in order to achieve those objectives, these main questions become the guideline:

(1) What are the factors and attributes comprising budget destinations in Southeast and Northeast Asia according to budget travelers?

(2) How to conceptualize the elements constituting the competitiveness of budget destinations in Southeast and Northeast Asia?

(3) What are the differences between the attitude of Asian and Western backpackers travelling in Southeast and Northeast Asian destinations?

1.4. Significance of the Study

This thesis aims to contribute both to academia and practitioners. The theoretical contribution of the study derives from its potential to cover some gaps in the discourse of backpacking or budget tourism by proposing a model for budget destination. By comparing the model of budget destination to other conventional models for generic travel, the research aims to find out distinctive factors driving budget travelers to a particular destination. This research also intends to complement the perspective on the differences between Asian and Western travelers, following up the previous works, e.g. by Muzaini (2006), Teo and Leong (2006), Bui et al. (2014), Cohen and Cohen (2014), Chang (2015).

5

Practically, the proposed model is useful as a framework for tourism professionals to develop their products and service, either for generic backpackers or Asian travelers who are increasing in great numbers. Moreover, the model of budget destination is more relevant and important for less-developed nations (Hampton, 1998) or third-world countries (Scheyvens, 2002), whereas budget tourism might have significant and direct positive impacts on local economy and society (Hampton, 1998; Scheyvens, 2002; Scheyvens & Momsen, 2008; Ooi & Laing, 2010; UNWTO, 2016).

1.5. Thesis Outline

This thesis consists of six chapters. Chapter 1 introduces the background to the research, the research questions and objectives, as well as its significance. Chapter 2 examines and synthesizes the previous works, covering the topics of backpackers and their characteristics, Asian backpackers, and destination competitiveness. At the end of the chapter, the synthesis results in a proposed model used in this research. Chapter 3 elaborates on the research methodology adopted, covering the research paradigm, data sources, analytical tools and approaches, procedure of data analysis, and the limitations of this research. Chapter 4 presents the findings according to both sources of data, which are the online forum (netnography) and autoethnography. Chapter 5 outlines the result of analysis and discussions on the findings, including the contrasting outcomes between two approaches used, as well as comparing it to previous studies. Chapter 6 provides the conclusions of the research, including how the research questions are responded, the theoretical contribution and practical implication, and future research directions that might be suggested from this research. And at the very end of the thesis, there are references and appendices.

6

CHAPTER 2. LITERATURE REVIEW

The literature synthesis is divided into four parts. The first part reviews the dynamics of budget travelers. The second part examines the previous works done on Asian backpackers focusing on their attitude. The third part evaluates the thoughts on existing models of destination competitiveness. And lastly, the fourth part is the synthesis of the literature review which results in an initial proposed model of budget destination called ‘6As of Budget Travel’.

2.1. The Evolution of Backpackers

The historical origin of backpackers started in the 17th century through “The Grand Tour”, when young upper-class Europeans from Victorian period set out on an adventure trip to far-away places, considering it as a part of their education or as a means of self-development (Locker-Murphy, 1995; Riley, 1988). In modern times, it then evolved into the phenomenon of wandering, drifting, and tramping as summarized by Dayour et al. (2017).

Meanwhile research on contemporary budget travelers derives from the original works of Cohen (1972; 1973; 1979; 1984), explaining tourist phenomenon from the sociological-anthropological approach. Cohen (1972) proposed four categories of tourists according to their attitude on novelty and familiarity. The categories are organized mass tourists, individual mass tourists, the explorer, the drifter. The former two belong to a category called “institutionalized”, while the latter two are “non-institutionalized”. Figure 2.1 visualizes the interpretation.

7

Figure 2. 1. Cohen's (1972) Typology of Tourists Source: Researcher’s interpretation

Backpackers are a part of the non-institutionalized tourists. Further on the classification of institutionalized tourists, “the explorers” would arrange the trip alone, to get off the beaten track as much as possible, but looks for comfortable accommodations and transportation. These tourists would be involved in the host community carefully, don’t immerse completely, and still retain the comforts of his native way of life. Meanwhile for “the drifters”, this type would consider the tourist experience as phony and tend to avoid tourism “industry” (as cited in Riley, 1988).

Since the inception of the typology, the academic landscape on backpackers has changed significantly (Cohen, 2011). The model has laid a foundation on the discourses of backpacking or budget travel. The discussion has been evolving greatly, variations of terms have been invented, definitions become richer, and characteristics conceived are described in more detail – from age category to their physical appearances. From the classical “drifter” or referred to as the root of “hippy” travelers (Hampton & Hamzah,

8

2010), to the mainstream “backpackers” that still look up to the “drifter” as its ideal model

of travelers (O’Reilly, 2006).

However, there is still no consensus of what makes traveler, a backpacker (Hampton & Hamzah, 2010). Other than the word “backpackers”, it comes with different

terms, such as drifters (Cohen, 1972), youth tourists (ten Have, 1974), wanderers (Vogt, 1976), international budget travelers (Riley, 1988), global nomads (Richards & Wilson, 2004), lifestyle travelers (Cohen, 2011), and other alternatives might keep being invented. In the early 1970s, ten Have (1974) published a paper about “youth tourists”,

describing budget travelers as:

“…between 15 and 30, travelling without their parents... Many of them don’t

live a normal, established, ‘bourgeois’ life…. when they are away from their home country for a longer period of time. They dress differently, wear their hair longer, use inexpensive means of transportation, living and recreation, and, in general, behave differently from the ways followed by the majority of the settled population or even the ‘normal’ tourists…” (p. 297)

Vogt (1976) used the term “wanderer” or “wandering youth”, to define youthful

adventurers on a tight budget with a sense of spontaneity in their travel style. He noted that the term “youth” might be misleading, as this kind of travel may attract other people from the older category as well. On the other hand, many youth travelers are also travelling in an institutionalized manner, adopting the typology by Cohen (1972; 1973). In his paper, the word “backpackers” was used in a phrase of “young backpackers” (Vogt, 1976, p.38), but it still takes years before the term gained popularity in the 1990s.

Riley (1988) proposed the term “international long-term budget travelers”. Her term derives from the category of non-institutionalized tourists, without differentiating the “explorer” and “drifter” like what Cohen (1972) did. However, she notes that the “drifter”

9

might be closer to the term since it describes travelers who travel on a low budget and unfixed itinerary. Yet the term” budget travelers” is used because at that time it was more frequently used by the travelers themselves and it has a less derogatory connotation. The definition is as follows:

“It refers to people desirous of extending their travels beyond that of a

cyclical holiday and, hence, the necessity of living on a budget” (Riley, 1988, p. 317)

Pearce (1990) popularized the term “backpackers” in his book: “The Backpacker

Phenomenon: Preliminary Answers to Basic Questions”. Dayour et al. (2017) argued that this is the first time the term “backpackers” was coined. However, it needs to be clarified that actually the word “backpackers” has appeared in the work by Vogt (1976, p. 38). Following the publication and previous works from other scholars, a research by Locker-Murphy and Pearce (1995) proposes five characteristics that define a backpacker:

a. A preference for budget accommodation

b. An emphasis on meeting others (locals and travelers) c. An independently organized and flexible travel itinerary d. Longer travel period rather than brief holidays

e. An emphasis on informal and participatory recreation activities

Despite those characteristics might arguably be the most frequently cited and referred as the standard qualities of backpackers, it is still critically questioned by some scholars. Dayour et al. (2017) argued whether a backpacker must meet all the criteria to be called as backpackers. Moreover, some phrases like “longer travel period” and “informal activities” are also ambiguous and vague to categorize and operationalize (Richards & King, 2003). However, since then the word “backpackers” has been widely

used in both academic and popular writings. Even it managed to replace some original-local words that have been used for a long time to define wanderers, such as “routards”

10

in French or “morchillos” in Spanish (Richards & King, 2003). The word has arguably become universal and globalized, but not its definition and characteristics for scholars.

Alternatively, Bradt (as cited in Hampton & Hamzah, 2010) defined the habitual of backpackers as their “badges of honor”, which are: survive on less than USD 15 per day, use local transport, carry the belongings on back, bargaining and guarding against rip-offs, get away from crowds and discover new places. Hampton and Hamzah (ibid) also offer a definition “tourists who travel with backpacks, live on a budget, and normally travel for longer periods than conventional holiday periods”. In spite of that, they do realize that the blanket terms are not helpful, considering the argument of Maoz (2007)

on the diversity and variety of the practice of backpacking itself. Backpackers are multi-faceted, diverse, and heterogeneous (Cohen, 2013; Maoz, 2007; Richards & Wilson, 2004; Sorensen, 2003; Uriely et al., 2002). As argued by O’Reilly (2006), the only thing backpackers have in common is: “travel”, hence other aspects would be subject to endless discussions. Sorensen (2003) contended the term “backpacker” is more of a social

construct and individual perception.

Since the introduction of the concept of “the drifter”, backpacking has changed from a minor phenomenon to a prevalent trend in tourism (Cohen, 1973). Backpacking which used to be considered as a marginal activity taken by society’s drop-outs has now gradually become mainstream tourism (O’Reilly, 2006). In other words, “nomadism” as argued by Richards (2015) is now an industry itself and no longer an alternative to tourism. The shift toward the institutionalization of backpacking tourism has inspired

11

Figure 2. 2. Cohen's (1973) Typology of “The Drifter”

Source: Researcher’s interpretation

The typology is based on two dimensions. The first dimension is the depth of involvement that measured by the amount of time devoted to the pursuit and the existence of other concerns, dichotomizing “part-time” and “full-time drifters”. While the other dimension concerns the motivation of drifting, whether one is primarily “outward-oriented” that prefers to experience the host-destination or “inward-“outward-oriented” which aspires to experience the youth-, sub-, or the counter-culture of their co-travelers, that often associated as “hippies”.

As a result, there are four categories of drifter from this typology. The “adventurer” is the authentic-original drifter referring to Cohen’s (1973) work, the original “backpacker” which is fast disappearing (Richards, 2015). The “itinerant hippie”

is defined as a drop-out from the society that travels to various enclaves aimlessly, from one community of hippies to another. The “mass-drifter” might represent the majority of contemporary backpackers nowadays. They are usually the college-youth, who spends a limited amount of time and seek the experiences, but still tend to stick to the drifter-tourist

12

establishments such as backpacker hostels. They usually are not interested to seek much adventure or mix with the local people and prefer to be left alone to do what they want to do. While the “fellow traveler” is those who associate with the hippies or other society drop-outs but still marginal to the sub-culture itself and might visit and get immersed in the community of hippies for a short period of time and then return to the original lifestyle. In conclusion, the concept of backpackers keeps evolving and there is no strong consensus of what backpacker is and its characteristics. The concept even becomes blurrier, due to the convergence with mainstream tourists. In practice as well as academic-wise, backpackers are indeed often associated and (still) dominated by Western travelers. However, nowadays there is a growing number of non-Western backpackers, including Asian backpackers that become one of the subjects in this research and are addressed in the next section.

2.2. Asian Backpackers

The research on Asia in the context of backpacking often treats Asia as a mere destination, that travelled particularly by Western backpackers particularly the middle classes of the white majority of their respective countries (Cohen, 2003), thus there is a need to decenter the orientation (Teo & Leong, 2006). However, there is a strong trend that Asian tourists are flocking to various destinations in Asia, and so are the Asian backpackers to the enclaves around Asia (Bui et al., 2014; Chang, 2015; Muzaini, 2006).

The trend of backpacking among Asian travelers is considered to be late in comparison to their Western counterparts. For Asian backpackers, the trend of backpacking was started arguably in the late 1980s by Japanese travelers who did individual arrangement (Andersen et al., 2000), which is still dominating the landscape

13

of researches on Asian backpackers nowadays (Bui et al., 2013; Bui et al., 2014; Huang, 2008; Muzaini, 2006; Teo & Leong, 2006). Recently, there is a strong growing interest of researches on backpackers coming from Asian nation other than Japan, that is China (Lim, 2008).

Cohen (2003) and Cohen and Cohen (2015) argue that there are differences between backpackers following their cultural background and suggested further researches on this matter – particularly between Western and Asian travelers, in addition to a few other segments such as Latin America travelers, working-class, and ethnic minorities in Western countries. As a response, there are a few studies that specifically take the differences between Asian and Western backpackers. A study by Huang (2008)

identified diverse motivations and travel choices between Western and Asian backpackers in Taiwan. It covers travel style, type of attractions, and advice taken in planning the trip.

Paris et al. (2015) conducted a study on 256 backpackers in Malaysia and Thailand, and the result revealed some distinctively different values between Australian and Asian backpackers, e.g., their average age, hedonistic aspects of backpacking culture, the pre-planning phase, and preference toward off-the-beaten-track destinations. Furthermore, from the perspective of tourism providers, a study by Teo & Leong (2006) in Thailand found that there are different treatments between Western and Asian backpackers by the businesses, particularly on Asian female backpackers.

Research suggests that there are differences among travelers coming from different cultural background. However, there are many similarities that they also share. For instance, a study by Huang (2008) indicates both Asian and Western travelers tend to travel with only one other person and to stay either in a hostel or family house, while many other attributes might only have a slight difference. Paris et al. (2015) found a degree of agreement between Asian and Western travelers on the use of social media,

14

risk-seeking motivation, and various social aspects of backpackers. Muzaini (2006) notes that both Western and Asian travelers demonstrate the same attitude to mimic or look like local people.

Nevertheless, this converging preference and attitude might also be caused by another factor, that is the mainstreamization of backpacking tourism which turns it into mass tourism (Cohen, 2003; O’Reilly, 2006) or low-budget mass-tourism (Spreitzhofer, 2002). This shifts backpacking, which was once categorized as a practice of the non-institutionalized tourists to enter the non-institutionalized tourist matrix, following Cohen’s

(1972) typology. Nevertheless, there is still a uniqueness among each group. Cohen (1995) argues that even though the backpackers coming from Asian background can be interpreted as a tourist in the Western sense, they may still incorporate particular elements from their cultural background. Moreover, there is still a minor number of authentic-original drifter remained, that termed as “the adventurer” (Cohen, 1973), despite the commoditization of backpacking tourism, in which they arguably still retain the unique and original characteristics of the drifter.

In summary, Asian backpackers might share similarities and show differences in comparison to their Western counterparts. To identify both becomes one of the objectives of this research. In order to achieve it, then they should be put in the context of this research – that is the destination competitiveness model.

2.3. Destination Competitiveness

Discourses on destination competitiveness can be traced back to the original theory of “competitive advantage” by Michael Porter (1980;1985), which inspired scholars to adopt it in the context of destination competitiveness. Among research on the topic of

15

destination competitiveness, much foundation for research on it is grounded on the works by Crouch and Ritchie (1999), Crouch (2011), Dwyer and Kim (2003), who proposed a generic and comprehensive framework for the assessment of destination competitiveness. This research will take them, plus another work by Buhalis (2000), as the main references to construct its proposed model.

According to Crouch (2011), the concept of comparative advantage in his model is represented by the destination’s resource endowments. Meanwhile the idea of competitive advantage is adopted in the form of the capacity of a destination to deploy its resources. The model ultimately consists of 36 attributes that grouped into 5 layers, which is a significant update from a previous model introduced by Crouch and Ritchie (1999), which involves only 19 attributes and 4 layers. The list of its attributes is as follows, ordered from the base to the top:

a. Supporting Factors & Resources (Infrastructure, Accessibility, Facilitating Resources, Hospitality, Enterprise, Political Will)

b. Core Resources & Attractors (Physiography & Climate, Culture & History, Mix of Activities, Special Events, Entertainment, superstructure, Market Ties)

c. Destination Management (Organization, Marketing, Quality of Service/Experience, Human Resources Management, Finance & Venture Capital, Visitor Management, Resource Stewardship, Crisis Management) d. Destination Policy, Planning, & Development (System definition,

Philosophy/Values, Vision, Positioning/Branding, Development, Competitive/Collaborative Analysis, Monitoring & Evaluation, Audit) e. Qualifying & Amplifying Determinants (Location, Safety & Security,

Cost/Value

Another popular model of destination competitiveness is proposed by Dwyer and Kim (2003), which also clearly states that the model is inspired by previous works particularly Crouch and Ritchie’s (1999) but differs in some aspects, e.g., demand

16

condition. This model determines indicators defining destination competitiveness. There are 12 elements proposed in the model including natural resources, heritage resources, created resources, supporting resources, government, industry, situational conditions, demand, destination competitiveness, socio-economic prosperity, destination competitiveness indicators, and quality of life indicators. The first two elements are termed as “endowed resources”, meanwhile the first four are categorized into a big group of “resources”. Meanwhile for “government” and “industry”, they belong to a category of “destination management”. Each element consists of attributes. However, Mazanec et al. (2007) criticize the model to be ambiguous in two points: whether it defines the operational of destination competitiveness or it proposes formative indicators that precede competitiveness in either definitional or causal sense.

Even more, the paper states that the indicators they propose are only “some” those are relevant and there might be other indicators that can be employed at another time. By the word “some”, the model by Dwyer and Kim (2003) has mapped more than 150 attributes in their table, classified into 12 elements. Meanwhile another related work by

Dwyer et al. (2004) proposed 83 attributes and 12 factors. As a summary, the model itself could be arguably holistic as it involves many considerations from the perspective of almost all stakeholders in the industry. Nonetheless, it might be not as generic as previous work by Crouch (2011) and could be not practical due to its complexity. But still, this research adopts the idea of that model, by excluding some irrelevant attributes using the same criteria.

Another model that plays an important role in this research is a work by Buhalis (2000), emphasizing on the marketing perspective, making it different from previous work. Its marketing perspective emphasizes on pull factors. Also, the model proposes an easy-to-memorize concept of 6As, which stands for: attractions, accessibility, amenities,

17

available packages, activities, ancillary services. The main influence of his model on this research is the wordings or phrases he uses.

There are dozens or possibly hundreds of works from other researchers and organizations on the destination competitiveness model. For instance, a research by Heath (2003) visualizes the framework as a house and its building components, which also inspires this research to visualize its proposed model for the sake of practicality. Another model by World Economic Forum (2017) offers a view from the macro-environment perspective. Having considered many models of destination competitiveness for the current study, Table 2.1 compiles 10 other models into a table to compare the factors and attributes used, as well as the unique attributes that appear in their research.

Table 2. 1. Destination Competitiveness Model from Previous Works Source: Researcher’s compilation

Researcher(s) Case # of Factors and Attributes Unique

attributes

Pearce (1990)

3 countries in Southeast Asia

6 factors: Market*, Access, Attraction, Accommodation, Price,

Development*

Hassan (2000) Environmental

sustainability

4 factors, 50 attributes: Demand orientation*, Comparative advantage, Industry structure, Environmental commitment

Heath (2003) South Africa

4 factors, 21 attributes:

Foundation, Cement*, Building blocks*, Roof*

A visualization of a "house"

March (2004) Australia

8 factors, 63 attributes: Accessibility, Attractors, Costs/Values,

Infrastructure, Consumer perception, Marketing management*, Linkages, Origin specific determinants

Cuisine, no language problems, ease of: getting around; combining travel to other destinations

18

Enright & Newton (2004)

Urban tourism

in Hong Kong 15 attractors and 37 business factors

Cuisine, Local way of life, Music and performances Gooroochurn & Sugiyarto (2005) Global, macro-environment 8 factors; 23 attributes; Price, Human tourism index*, Infrastructure, Environment, Technology, Human resources*, Openness, Social development

Lee & King (2006)

Hot springs in Taiwan

3 factors, 19 attributes;

Tourism destination resources & attractors, Tourism destination environments, Tourism destination strategies* cuisine, community participation and attitudes, Kozak et al. (2009) Turkey 4 factors, 23 attributes;

Facilities and activities, Cultural and natural attractiveness, Quality of services, Infrastructure Diversity of tourism products, distance to home country Cibinskienea & Snieskieneb (2015) City tourism in Lithuania 7 factors, 51 attributes

External environment (political and legal, economic, social & cultural, ecological & natural), Internal environment (Tourism enterprises, Tourism resources, Infrastructure)

Culinary heritage, World Economic Forum (2017) Global, macro-environment

4 factors & 14 attributes;

Enabling environment, T&T policy & enabling conditions*, Infrastructure, Natural & cultural resources

ICT, International openness

To summarize, there are four main models that become the major part of this research. While other 10 models which take place in different context contribute to enriching and complementing the possible attributes that the previous models might miss to capture. These models are useful in formulating the proposed model, which is elaborated in the next section of the synthesis of literature review.

2.4. Synthesis and Proposed Model

This synthesis summarizes, connects the parts of literature review, and provides a premise to answering the research questions. The first and second part of the literature

19

review deals mostly with the internal factors that drive travelers to visit destinations. While the third part focuses more on the external factors that attract travelers to come to a destination. In other words, the first two parts are the “push” factor that orientates mostly on the travelers themselves or the demand side, while the third part is the “pull” factor that concerns with the destination management itself or the supply side, quoting the concept of “push and pull factors” by Dann (1977).

The focus on the backpackers in literature review gives foundations on definitions, backpacker characteristics, typologies, and discussion on Asian backpackers. However, as argued by Sorensen (2003), the relative and subjective interpretation of the word “backpackers” makes it an ideal ethnographic object. This research intends to continue that academic tradition by exploring the niche of research by using ethnography as one of its approaches. Moreover, considering the evolution of terms and diverse interpretations of the terms, then this research decides to treat the word “backpackers” and “budget travelers” as identical and interchangeably used.

Nevertheless, there is still a need to set a working definition of the subject of this research. Considering a wide spectrum of definitions on backpackers (Cohen, 1972; Cohen, 2011; ten Have, 1974; Richards & Wilson, 2004; Riley, 1988; Vogt, 1976) and its characteristics (Hampton & Hamzah, 2010;Locker-Murphy & Pearce, 1995), then this research takes only two essential characteristics of backpackers which are assumed to be the unanimous qualities of backpackers which differentiate them from regular tourists. Travelling on budget and long period of travel. For its operational or working definition, it can be described as follows.

“those who travel on (low) budget, very cost-conscious, or price-sensitive; and travel for a long period of time - more than a month away from his or her own country”

20

The amount of budget to define ‘low’ cannot be specified since it depends much on the standard living-cost in the destinations. Bradt (as cited in Hampton & Hamzah, 2010)

suggests a threshold of USD 15 per day, but this might not work in the case of destinations in developed nations, which will exclude the possibilities of backpackers to exist in destinations like Japan. Meanwhile the threshold of one month is adopted here to differentiate it from regular tourists as well as business tourists. Some researchers such as Riley (1988) suggests a threshold of 1-year. However, it might not be realistic to be implemented in the research which intends to capture the attitude of Asian travelers as well. Prior knowledge of the researchers found that only a few Asian backpackers travel for more than a year.

On the other hand, this loose definition provides some advantages of inclusiveness to some extent. It includes backpackers that might come from different categories of age and whether they are travel solo or in a group. It covers recent trends in backpacking practices such as Couchsurfing and hitchhiking, defying the classical characteristics of preference on budget accommodation (Locker-Murphy & Pearce, 1995) and local transportation (Hampton & Hamzah, 2010). It also does not limit the backpacker to be defined through specific activities, communication styles, or immersion levels within the host society, meaning it captures the large segment of budget travelers who might have limited contacts with locals or join organized tours such as defined as the “mass drifter” by Cohen (1973); which arguably now accounts as the largest sub-segment of the so-called backpackers due to mainstreamization. In other words, this loose definition tries to cover a broad segment of backpackers, including the majority of them. Consequently, the research manages to get more subjects or samples that can be categorized as backpackers, though it might be too diverse as its downside.

21

While for destination management, the literature review covers the discourses on external factors that attract travelers to come according to both generic and particular cases, which greatly inspired from the works from Buhalis (2000), Crouch and Ritchie (1999), Crouch (2011), Dwyer and Kim (2003), and 10 other models of destination competitiveness. The insights from those discourses are helpful in formulating the initial model proposed in this research that specifically tailored for budget travelers. Nevertheless, it should be noted that not all factors from previous models discussed are relevant to the research context. The justifications are either one of these three reasons: they are not pull factors, they are not related to the perception of travelers, or they are more of the domain of stakeholders that don’t have direct roles in the supply side.

The initial model derives from the extraction of attributes of previous models. There are more than 10 models extracted, resulting in hundreds of factors and sub-factors that this research terms as ‘attributes’. Those attributes are then synthesized and categorized, generating a final list of 31 attributes that categorized into 6 main factors as its parent category. Each factor has an attribute of ‘others’ that functions as an umbrella covering those who don’t belong to any existing category.

The model is proposed under the name of ‘6As of Budget Travel’. The wording is inspired partly from the wordings proposed by Buhalis (2000), adopting the same abbreviation of ‘6As’ but using some different components, especially for the latter two. Table 2.2 below lists of factors and attributes that constitute the 6As of Budget Travel proposed in this research, followed subsequently by the elaboration of each factor and attribute.

22

Table 2. 2. The Proposed 6As of Budget Travel Source: Researcher’s compilation

Factors Attributes

Affordability price, exchange rate, work availability, others

Attraction cultural, natural, artificial, cuisine, events & activities, market ties, diversity of attraction, others

Accessibility entry and exit, visa, get around, proximity, easiness to combine with other destinations, others

Amenities communication/internet, financial service, accommodation, food service, tour operators, others

Atmosphere service or hospitality, local community atmosphere, safety and security, others

Amplifier image & awareness, capacity, market ties, others

Affordability

This research comprehends affordability as something more complex than merely price or cost that tourist spends in exchange for service. Instead, it is understood as the way money is spent, used, saved, or earned that affects the attractiveness of a destination in the eyes of budget travelers. That is the reasoning behind why the attribute ‘work availability’ presents in the model and is put under this category.

‘Price’ is arguably the most basic feature in any product offerings. And tourism is no exception in which this attribute is mentioned in many works (Crouch & Ritchie, 1999; Dwyer & Kim, 2003). The straightforward interpretation of competitiveness in the context of tourism destination is likely to focus on its price (Mazanec et al., 2007). Moreover, this attribute is more essential in the context of budget travelers and marks an obvious difference than regular tourists (Cohen, 1972;Riley, 1988; ten Have, 1974). In addition, the attribute “exchange rate” appears in many academic works (Buhalis, 2000; Crouch & Ritchie, 1999; Dwyer & Kim, 2003; March, 2004).

23

Meanwhile the attribute “work” is perhaps the most distinctive to backpacker destinations. Cooper et al., (as cited in Richards & Wilson, 2004) find a strong relationship between backpackers and employment in the harvest industry in Australia. The relation between work and travel mostly appears in the context of business trip destinations or the backpacker’s dimension of “work to travel” (Cohen, 2011) – but not in the discussion of destination competitiveness. As its working definition in this research, this attribute can be interpreted as an opportunity to work while travelling or staying in a destination.

Attraction

The factor “attraction” is traditionally seen as the most essential thing that draws people to leave their home and visit a place. A study by Crouch (2011) found that the “core resources and attractors” is the most significant factor among others. This research treats this factor to be constituted of 8 attributes. They are: natural, cultural, artificial, cuisine, events & activities, market ties, attraction diversity, and “others” that cover any aspect that can’t be categorized into the aforementioned categories. The first four attributes are the type of essential or core attractions that are the main drivers in drawing tourists to visit. Meanwhile the latter four act as an enhancer.

Natural and cultural attractions need no further explanation since they are the most obvious type of attractions and never been not mentioned in any model. As for the artificial attraction, the working definition of this attribute is a type of attraction that unnaturally exists, to be created in contemporary times, and neither natural- nor cultural-based. The examples are theme parks, waterparks, modern landmarks, shopping malls, casinos, adult entertainments, and so on. In previous works, this attribute is equal to

24

“purpose-built” (Buhalis, 2000), “created resources” (Dwyer & Kim, 2003, p.400), “special attractions” (Lee & King, 2006), “leisure activities” (Hassan, 2000), and others. Meanwhile for the attribute ‘cuisine’, some works categorize it as a part of cultural attractions (Buhalis, 2000; Dwyer, 2003). Nevertheless, some treat this attribute as an independent attribute (Enright & Newton, 2004; Lee & King, 2006; Cibinskienea & Snieskieneb, 2015; March, 2004) or even a specific type of tourism which goes under the name “food tourism” (Cohen & Avieli, 2004; Hall et al., 2011, Henderson, 2009; Rand & Heath, 2008), “culinary tourism” (Karim & Geng-Qing Chi, 2010; Long, 2004; Smith & Xiao,2008), or “gastronomic tourism” (Kivela & Crotts, 2006; Sánchez-Cañizares & López-Guzmán, 2012). Food tourism is also regarded as a great attractor for youth travelers (UNWTO, 2016). Those core attractions can be enhanced through events and activities. Many literature categorize “events”, “special events”, or “festivals” as an independent attribute that makes an attraction (Buhalis, 2000; Crouch, 2011; Enright & Newton, 2004; Heath, 2003; Lee & King, 2006; March, 2004).

Several works mention the importance of diversity as an attribute in destination management. March (2004, p.11) uses the term “experiences diversity” and puts it under the consumer’s perception which is parallel to the factor ‘amplifier’ in this research.

Dwyer & Kim (2003, p. 382) adopts the term “mix of activities” that introduced by Crouch & Ritchie (1999) and Crouch (2011). Meanwhile the exact term used in this research, “diversity of tourism products”, is directly borrowed from a study by Kozak et al. (2009).

25 Accessibility

The factor ‘accessibility’ is defined as physical access that connects travelers to a destination. Thus it deals mostly with the infrastructures, options of transportation modes, and other related dimensions. It is an integral part for travelers. Travel route is one common topic to discuss among travelers (Murphy, 2001). Budget travelers are no exception, in which Cohen (1973) notes that the transportation and accommodation industry itself had evolved due to the emergence of the drifters. And virtually all works on destination management include it as an important competitiveness attribute. In a study by Crouch (2011), accessibility is ranked number one as an attribute of supporting factors and resources. While Cooper et al. (as cited in Richards & Wilson, 2004) reveal that backpackers might follow a certain route, which doesn’t always refer to a destination having certain attractions in a conventional sense, but the job opportunity there.

There are six attributes constitute this factor: entry and exit, visa and travel permit, getting around, proximity, ease of combining with other destinations, and others. The first three attributes deal with the technical side of accessibility, that is transportation options and administrative requirement. The last three attributes denote the tendency of backpackers in visiting multiple destinations.

The issue of entering a destination is often an important discussion for travelers, either it means entering a country or visiting another destination while already in a country. Together with ‘getting around’, the discussions around this attribute are among the main topics on websites that often referred by backpackers, such as Lonely Planet, Wikitravel, and Wikivoyage. The phrase itself, ‘getting around’ is directly borrowed from the structure of the travel website Wikitravel.org. As for visa and travel permit, its working definition in this research should be understood as an official permit that allows a movement of a traveler into a country or a destination legally.

26

The attribute “proximity” implies the distance from one destination to another. On the ground level, it means the physical destination location that affects the travel time (Dwyer & Kim, 2003) or the distance to home country (Kozak et al., 2009). The distance to home country itself is closely associated with the sense of “safety” in a destination (Paris et al., 2015), in which the closer is often perceived to be safer. As a practical example in the field of destination management, Crouch and Ritchie (1999) argue that Hawaii is taking benefits as a stopover destination since a sizeable portion of tourists is en-route to or from other Asia-Pacific nations.

However, most backpackers are not only going from their home country to a destination and returning back, but they do a series of trips which termed in this research as ‘multiple destinations’. Thus, this research takes the interpretation further and wider by translating it as a distance between one destination to others, as well as the availability of the next destination. The context is not necessarily across countries, but also destinations within the same country. This attribute is also closely related to “easeness of combining travel to other destination”, a term that directly borrowed from March (2004).

Amenities

This research interprets this factor as the physical and digital infrastructures that support the tourism industry in a destination. Virtually all previous works mention the importance of infrastructures in a destination, though different terms and categorizations are used. Buhalis (2000) uses the terms ancillary services to define general infrastructure and amenities for tourism services. Dwyer and Kim (2003) put general infrastructure as supporting resource, while tourism infrastructure as a created resource, similar to the work by Crouch and Ritchie (1999).

27

In this research, the factor consists of two big parts: general and tourism infrastructure, in which each consists of several attributes. The general infrastructure is represented by communication provider, financial service, Meanwhile the tourism infrastructure consists of accommodations, food services, tour operators. In addition, there is ‘others’ which essentially are public utilities and miscellaneous tourism ancillary services that can’t be categorized into an umbrella of category, such as hospital, drinking water, to sanitation facilities like toilet.

Communication provider is the infrastructure that enables travelers to communicate with others, either through conventional or digital media. It ranges from post office to internet provider. Financial service constitutes of various financial services, such as ATM, banks, money changers, the acceptance of credit cards and digital money, and so on.

Accommodation covers a wide range of places to stay in a destination such as hotels, guest houses, hostels, ryokan in Japan, dorms, and so on. As for the food service, the attribute represents the places where tourists eat and it takes many forms. From restaurants to street food vendors. This attribute is closely related to the attribute ‘cuisine’, in which the difference is that it is more of an infrastructure to cater to the travelers. Both accommodation and food service should be understood in the context of budget travelers, thus the more specific terms for them are ‘budget’ accommodation and ‘budget’ food service options.

Atmosphere

This factor is the ambiance that the tourists feel while being in a destination. If the factor ‘amenities’ is considered as the physical hardware, then ‘atmosphere’ is the

28

software. The proposed model argues this factor constitutes of three attributes plus the ‘others’. The three attributes are the interaction with the local host community, the quality of service or hospitality by the people in tourism industry, and the political situation as well as the safety and security condition of a destination.

The interaction with local host community is shortened into ‘local atmosphere’. Different terms are used in other works to describe this attribute, such as “local way of life” (Enright & Newton, 2004) and “community participation and attitude” (Lee & King, 2006). In wider interpretation, it also refers to “hospitality” that defined as perceived

friendliness of the local population and attitude toward tourists (Dwyer & Kim, 2003). The second attribute is ‘hospitality or service quality’, that also found in many previous works using exactly the same term “quality of service” (Crouch, 2011; Kozak et al., 2009) or hospitality (Dwyer & Kim, 2003). It is almost identical to the attribute that has just been discussed. The difference is that the hospitality ambiance created here is derived from the tourism industry – or specifically the professionals. It includes the service or hospitality performed by hostel staffs, street vendors, tour operators, tuk-tuk drivers, ticketing officers, and so on.

As for the attribute ‘safety and security’, some tourist attractions itself are obviously based on “risk” in a broader sense (Buckley, 2012; Hunter-Jones et al., 2008). The manifestation of this factor might take different forms. Crotts (as cited in Dwyer and Kim, 2003) provides a long list of them such as political stability, probability of terrorism, crime rates, transportation safety, corruption, quality of sanitation, disease, reliability of medical services, and so on. Nevertheless, many works put “safety and security” as an important attribute. Heath (2003) regards safety and security as a fundamental non-negotiable. Crouch (2011) treats this attribute as the amplifying and qualifying

29

determinant, and found it to be the fifth most important sub-factor. Meanwhile a study by

Enright & Newton (2004) suggests that safety is the most important attractor. And even more, Hunter-Jones et al. (2008) summarize that the effect of risk perception of a destination might also affect the neighboring destinations, making it related to the previous attribute ‘proximity’ and asserting its importance in driving the competitiveness in a destination.

Amplifier

This is the last factor in the proposed model. While the previous factor mostly deals with post-travel, this factor is more of pre-travel perception. In the marketing mix or 4Ps, this corresponds to the “promotion” part that shapes and amplifies the perception of the market toward a product. In the context of tourism, this attribute depicts the perception of travelers toward a destination and the attributes attached to it.

The concept and the wording of this factor ‘amplifier’ is directly borrowed from works by Crouch and Ritchie (1999) and Crouch (2011), though the attributes that constitute the factor are modified into the context of backpacking tourism. This research interprets that there are two main categories constitute this factor. The first one discusses the perception of destination, that covered by the attribute ‘image & awareness’ and ‘capacity’. While the latter one discusses the market reach extension, which defines the source of the alternative market segment for a budget travel destination.

The attribute ‘image & awareness’ is related more to the perception of the demand side. For demand to be effective, tourists must be aware of a destination. Thus, the actual visitation of tourists will depend on the match between tourist preferences and perceived offerings (Dwyer & Kim, 2003) – which are made up of attributes that have been

30

discussed. Meanwhile for the attribute ‘capacity’, this attribute focuses more on the supply side. The most relevant phenomenon for backpackers that portrayed by this attribute is overtourism, which happens when the carrying capacity is not sufficient to facilitate tourist influx. On one occasion, it might even trigger the anti-tourist movement from local communities such as what happened in many European cities, namely Spain, UK, and Italy (Milano et al., 2018).

Meanwhile for market ties, there are many different terms used in previous works to describe this attribute, though the most used ones are “market ties” (Crouch & Ritchie, 1999; Crouch, 2011; Dwyer & Kim, 2003; Enright & Newton, 2004) and the “linkage”

(Dwyer in Heath, 2003; March, 2004). As indicated by its phrase, the attribute should be interpreted as the association between a destination and the market origin. The linkage or ties could be either ethnic, cultural, religious, education, visiting friends, business, and others.

The rationale of each attribute and factor has been explained, including their working definition adopted in this research. In short, all the items are extracted from the previous models developed by scholars, taking the relevant components from each of them, categorize them into a certain attribute sharing similar characteristics, group them into a parent category or factor, and connect all of the factors to construct the ‘6As of Budget Travel’ model. That is how the synthesis and formulation of a proposed model are developed in this research. In addition, this model lays a context foundation to answer the differences between Asian and Western travelers. Figure 2.3 summarizes the conceptual model which explains how this synthesis addresses the research questions.

31

Figure 2. 3. How Synthesis on Literature Review Addresses Research Questions Source: Researcher’s interpretation

2.5. Chapter Summary

This chapter starts with the introduction of the dynamics in the discourse of backpackers. It covers the definition and characteristics according to various scholars and particularly the niche of backpackers based on its cultural background, which is Asian backpackers which become a specific subject in this research. It helps to build the concept of backpackers and Asian backpackers that adopted in this research, which can assist the analysis process later. It is then continued by putting that understanding into the context of this research, which is the destination competitiveness. These reviews are synthesized and it results in a proposed model named “6As of Budget Travel”. The model will be verified through the findings from the data collected on the online forum and autoethnographic works. The detail on how the procedure will be done is discussed in the next chapter.

32

CHAPTER 3. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This chapter comprises four main segments. The first one discusses the research paradigm and design which justify the selection of the mixed approach. The second segment, that consists of three subsections, elaborates on the technical aspects by explaining the analytical tools used such as content analysis, autoethnography, grounded theory. The third one explains the procedure of data analysis. The last segment outlines the constraining issues, such as validity and limitations of this research.

3.1. Research Paradigm

This research adopts a constructivist paradigm. The goal of this paradigm is to achieve what Max Weber termed as “verstehen”, meaning “empathetic understanding” of a phenomenon (Jennings, 2001). This paradigm assumes that the reality is simply based on the subject and the researcher (Smith, 2010), thus the research believes in the existence of multiple realities, rather than an objective reality. Having adopted this paradigm, the researcher must enter the social setting and become one of the social actors in it (Blummer as cited in Jennings, 2001). It is an assertion of an argument on the subjective paradigm in which the researcher has to be an insider (Smith, 2010; Neuman, 2011). That epistemological view of constructivism also affects the methodological basis of how this research will be designed. This research summarizes and visualizes the research design through a model proposed by Maxwell (2013) as seen in Figure 3.1 below.

33

Figure 3. 1. Research Design

Source: Researcher’s interpretation of a model by Maxwell (2013)

This research has an objective to conceptualize a model that specific for budget destinations in Southeast and Northeast Asia according to the perspective of budget travelers, as well as to understand the differences between Asian and Western travelers. As a reflection of “multiple realities” in the constructivist paradigm, the research takes two sources of data to represent budget travelers, which are data on online forum (netnography) and 3-year autoethnography works.

The combination of multiple approaches mentioned might qualify this research as using a mixed or triangulation approach. Scholars don’t reach a consensus on what type of research counts as triangulation. Neuman (2011, p. 166) describes four alternatives of triangulation: data triangulation, investigator triangulation, theory triangulation, and methodological triangulation. Yet another author like Smith (2010)

argues triangulation should be mainly referred as the use of multiple sources only and suggests that if the sources employ different methods, it is more correctly described as “multiple methods” approach. Nevertheless, there is a bottom line for the relevance of