Abstract Although it is difficult for observers to determine how non-human primates use olfaction in a natural environment, sniffing is one clue. In this study, the sniffing behaviors of wild chimpanzees were divided into six categories, and sex differences were found in most categories. Males sniffed more fre- quently than females in sexual and social situations, while females sniffed more often during feeding and self-checking. Chimpanzees sniffed more frequently during the dry season than during the wet season, presumably due to the low humidity. This suggests that the environment affects olfactory use by chimpanzees and that chimpanzees easily gather new information from the ground via sniffing.

Keywords Chimpanzees Æ Olfaction Æ Sex differences Æ Seasonality

Introduction

In diurnal primates, although vision is thought to be the primary sensory modality, many studies have demonstrated the existence of scent glands and the importance of olfactory communication (see Kappeler 1998). Some studies have examined the importance of olfactory cues during food detection (Dominy et al. 2001), and many more have examined the importance of olfaction during social and sexual communication. Prosimians and New World monkeys show active marking behavior in their daily life, and sniff each other’s genitalia (see Oppenheimer 1977; Kappeler 1990; Heymann1998; Palagi et al.2003). Scent marking behaviors in Old World monkeys have also been re- ported in mangabeys (Cercocebus spp.) and Mandrillus (Fesitner1991).

In humans, many studies have focused on odor in a sexual context. A study has shown that the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) genotype influ- ences mate choice and that this choice is based on body odor (Ober et al. 1997). Women were found to prefer the odor of T-shirts worn by men who had MHC alleles that differed from their own (Wedekind et al.1995). In another study in which women sniffed men’s T-shirts in a box, the participating women had more favorable impressions of the scents of men who shared some of their genes (Jacob et al.2002).

Studying the great apes could provide important information on the sense of smell in primates. To date the olfactory-guided behaviors reported in great apes are limited to chimpanzees, and no quantitative data have been reported, likely because it is difficult for observers to judge the strength and quality of a smell objectively. Sniffing is a behavior related to olfaction A. Matsumoto-Oda (&)

Department of Welfare and Culture, Okinawa University, 555 Kokuba, Naha, Okinawa 902-8521, Japan

e-mail: matumoto@okinawa-u.ac.jp N. Kutsukake

Department of Biological Sciences,

Graduate School of Sciences, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

K. Hosaka

Faculty of Child Studies, Kamakura Women’s University, Kanagawa, Japan

T. Matsusaka

Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan

DOI 10.1007/s10329-006-0006-1

S H O R T C O M M U N I C A T I O N

Sniffing behaviors in Mahale chimpanzees

Akiko Matsumoto-Oda Æ Nobuyuki Kutsukake Æ Kazuhiko Hosaka Æ Takahisa Matsusaka

Received: 1 November 2005 / Accepted: 30 May 2006 / Published online: 27 July 2006 ÓJapan Monkey Centre and Springer-Verlag 2006

that observers can recognize easily. It is defined as bringing the nose close to something in the environ- ment, such as the ground or vegetation, to obtain information – for example, to judge the ripeness of fruit (Goodall1989; Nishida et al.1999). Chimpanzees often sniff the ground when their companions leave them behind. It is suspected that wild chimpanzees use olfactory clues in several contexts to receive important information.

This study examined how chimpanzees (Pan trog- lodytes) use olfactory clues in the wild by categorizing the recorded sniffing behaviors. We then analyzed the factors affecting the variation in behavior frequency in each category.

Methods

Study site and subjects

The subjects were chimpanzees of the M-group in the Mahale Mountains National Park, Tanzania. The data used in this study were collected by AMO, NK, KH, and TM from October 1991 to February 1992, March 1993 to February 1994, and September 2000 to Sep- tember 2001. The M-group comprised between 51 and 81 individuals during this time. The focal individuals during the study periods were 22 males and 20 females. A ‘‘sniff’’ is a type of behavior in which a chim- panzee puts its nose close to something in the envi- ronment, such as the ground, vegetation, a tree trunk,

fruit, a food wad, feces, or urine, among others (Goo- dall 1989; Nishida et al. 1999). We classified sniffing behaviors into six categories according to context, as summarized in Table1. Within the total observation time of 2212.8 h, 125 cases of sniffing behaviors by adults and adolescents were recorded. Since it was difficult to distinguish the sniffing behavior of imma- ture animals from other activities, such as play, we analyzed only sniffing behaviors by adults and adoles- cents. We also recorded the turgidity of genital swell- ing (flat, semi-swelling, maximum swelling) observed in the sexual context.

The Mahale Mountains have one dry season and one rainy season each year. We divided the data into two seasons by rainfall pattern (dry: from mid-May to October; wet: from November to mid-May). Each focal animal was observed for at least 1 h each in two con- secutive seasons. The total observation time during the dry and wet seasons was 1263.8 and 949.0 h, respectively. Statistical analysis

For the frequency of sniffing behaviors (n/10 h) re- corded by each observer, two-way repeated measures ANOVA was used for matched-pair comparisons of the interactions between season and sex.

Results

The results of the ANOVA indicated that the effects of season and sex on the frequency of sniffing behaviors

Table 1 Six contexts of sniffing behaviors in wild chimpanzees at Mahale, Tanzania

Contexts Behaviors

Feeding Chimpanzee sniffs food. Chimpanzee brings his/her nose close to food or puts food in mouth without biting. Chimpanzee puts back food when he/she does not eat it Sexual Adolescent or adult male sniffs female’s sexual skin or genitalia

directly or his finger which touched it. Nishida (1997) named the behavior as ‘‘genital inspection’’

Vigilance against predators Sniffs the feces or hairs of leopards or sniffs the ground when the researcher has information that a predator has used the place that day, based on sounds, feces, or footprints. Alternatively, chimpanzees sniff the ground when observers know that a leopard had passed that location based on information such as its roar within 1 h of the chimpanzee sniffing, or feces or footprints near by. Chimpanzees are often nervous

Social information (inter- and intra- group)

Chimpanzee stops moving and sniffs the ground repeatedly when he/she moves dispersively. He/she often sniffs at partings of research trails or entrance to animal trails Self checking After scratching his/her body or touching his/her genitalia,

chimpanzee sniffs his/her finger or hand

Others Chimpanzee sniffs other objects (e.g., plant item, feather, another individual, etc). Include cases in which the researcher cannot specify any contexts

were significant (Fig.1; season: F=4.88, df=1, 40, p=0.03; sex: F=6.82, df=1, 40, p=0.01). Males per- formed sniffing behaviors more frequently than fe- males. Sniffing behaviors occurred more frequently in the dry season than in the wet season. In particular, males sniffed more frequently in the dry season, while the interaction between season and sex was marginally significant (F=3.73, df=1, 40, p=0.06).

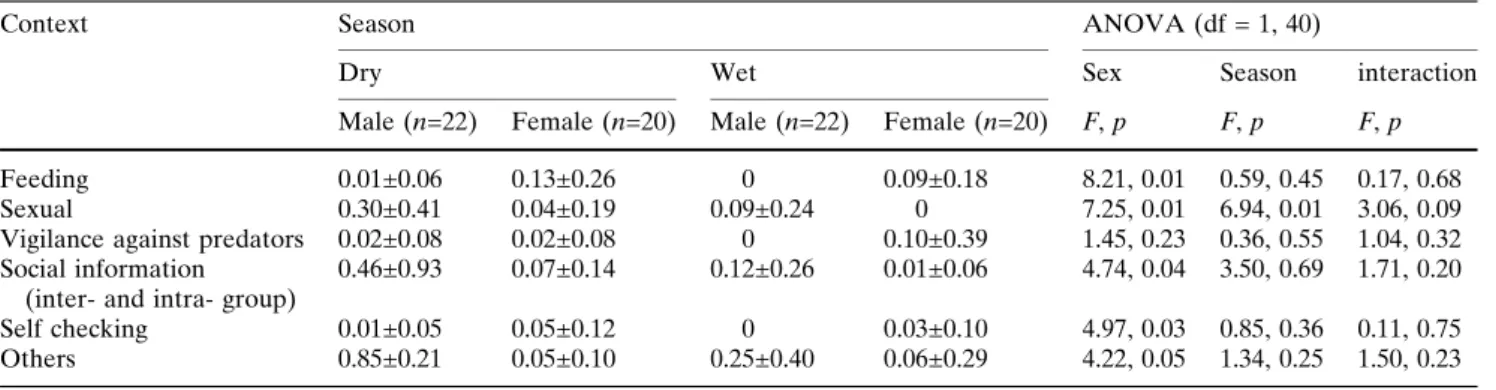

In most contexts, with the exception of vigilance against predators, sex differences in sniffing behaviors were observed (Table2). Males sniffed more fre- quently in social and sexual contexts. In 30 of 31 cases of social context, males sniffed in the central part of the range; the one exception involved sniffing on a patrol after hearing the vocalizations of a neighboring group. Anestrous females participated in many cases of sexual context (n=28; flat: 67.9%, semi-swelling: 10.7%, maximum swelling: 21.4%). In contrast, females sniffed more frequently in the context of feeding and self- checking. No significant interaction was found for any context.

A seasonal difference in sniffing behaviors was found only in a sexual context and was more frequent in the dry season.

Discussion

Our results revealed that chimpanzees use olfactory clues in various situations year-round. We also ob- served sex and seasonal differences in the sniffing behaviors according to the context.

Males sniffed most frequently in a social context. Patrol-type sniffing behaviors have been reported in Gombe (Tanzania), Taı¨ (Coˆte d’Ivoire), and Kibale (Uganda) (Goodall 1986; Boesch and Boesch-Acher- mann 2000; Watts and Mitani 2001). This type of sniffing could be regarded as a male activity because males generally perform territorial patrols (Watts and Mitani 2001). Chimpanzee group relationships are exclusive, and group encounters may result in fatal violence (Goodall 1986; Boesch and Boesch-Acher- mann 2000; Nishida et al. 2003). Nevertheless, we found that males sniffed in a social context, primarily in the central part of the range, with one exception (sniffing on patrol after hearing the vocalizations of a neighboring group). The chimpanzee social system is characterized by fission-fusion. Individuals form tem- porary small parties or subgroups whose members belong to a larger group with stable membership. Males are more political than females (de Waal 1982; Nishida 1983). Under a fission-fusion social system, individuals may not even meet others, even in the central part of the range, and odor is therefore useful in such a social system. These findings suggest that males sniffed in a social context to collect intragroup infor- mation and to manipulate relationships between members, including themselves.

In a sexual context, males performed the most sniffing behaviors. Female chimpanzees have a 35-day

0 1 2 3 4 5

Dry Wet

Season

Male Female

Frequency of sniffing behaviors (n/10 h)

Fig. 1 The effects of season and sex on the frequency of sniffing behaviors

Table 2 Frequency of sniffing behaviors in six types of context (n/10 h)

Context Season ANOVA (df = 1, 40)

Dry Wet Sex Season interaction

Male (n=22) Female (n=20) Male (n=22) Female (n=20) F, p F, p F, p

Feeding 0.01±0.06 0.13±0.26 0 0.09±0.18 8.21, 0.01 0.59, 0.45 0.17, 0.68

Sexual 0.30±0.41 0.04±0.19 0.09±0.24 0 7.25, 0.01 6.94, 0.01 3.06, 0.09

Vigilance against predators 0.02±0.08 0.02±0.08 0 0.10±0.39 1.45, 0.23 0.36, 0.55 1.04, 0.32 Social information

(inter- and intra- group)

0.46±0.93 0.07±0.14 0.12±0.26 0.01±0.06 4.74, 0.04 3.50, 0.69 1.71, 0.20

Self checking 0.01±0.05 0.05±0.12 0 0.03±0.10 4.97, 0.03 0.85, 0.36 0.11, 0.75

Others 0.85±0.21 0.05±0.10 0.25±0.40 0.06±0.29 4.22, 0.05 1.34, 0.25 1.50, 0.23

menstrual cycle, and their genital areas swell for about 11 days. Most copulation occurs during the period of maximum swelling. A previous study indicated that flat females were inspected one and half times more fre- quently than those in maximum swelling and that the frequency of male inspections was correlated inversely with the first day of maximal swelling (Wallis 1992). Nishida (1997) suggested that males gather informa- tion on the onset of swelling. In a preliminary chemical study, however, no differences were detected in the amounts of fatty acids or mucus between the flat and semi-swollen periods (Matsumoto-Oda et al. 2003). Another possible reason is that males are interested in menstrual bleeding, which occurs during the flat peri- od. More detailed observational and chemical studies are needed to determine whether male sniffing behavior is concentrated in the menstruation period.

Females sniffed more during feeding and self- checking. To achieve reproductive success, it is important for females to increase feeding efficiency. Sniffing during feeding was reported in both Mahale and Gombe (Wrangham 1977). Since ripe fruits pro- vide more energy, chimpanzees might feed on ripe fruits selectively. We were not able to determine a reason for the sex difference in self-checking.

There was no sex difference in the context of guarding against predators. Lions occasionally eat chimpanzees in Mahale. Although there is no evidence of leopard predation on M-group chimpanzees, they showed apparent vigilance based on vocalizations (e.g., wraa calls) in response to auditory/visual contact with leopards.

Sniffing behaviors were observed more frequently in the dry season than in the wet season. In the chim- panzees of Mahale and Gombe, females tend to re- sume swelling cycles during the late dry season (Nishida et al.1990; Wallis1997), and food availability is suggested to be a critical factor.

Our study suggests that invisible olfactory chemicals affect primate behavior. One group of olfactory studies has examined the hypothesis that positive evolutionary pressure leads a species or line to develop pseudoge- nes. The habitation environment has been suggested as a possible selection pressure. If chimpanzees as frugi- vores use odor to investigate the degree of fruit ripe- ness, frugivores might sniff more often than folivores. Moreover, a sex difference in sniffing behaviors was observed according to context. In the future, it would be interesting to investigate the relationships between sex differences in sniffing behaviors and social behav- iors in other species. Further studies of great apes are required, both in the wild and in enclosures.

Acknowledgments We are grateful to the Tanzania Commis- sion for Science and Technology, Tanzania National Parks, the Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute, and the Mahale Mountains Wildlife Research Centre for permission to conduct the present research. This study was supported by a grant of the Okinawa University to AMO.

References

Boesch C, Boesch-Achermann H (2000) The chimpanzees of the Taı¨ Forest: behavioural ecology and evolution. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Dominy NJ, Lucas PW, Osorio O, Yamashita N (2001) The sensory ecology of primate food perception. Evol Anthropol 10:171–186

Fesitner ATC (1991) Scent marking in Mandrills. Folia Primatol 57:42–47

Goodall J (1986) The chimpanzees of Gombe. Harvard Uni- versity Press, Cambridge

Goodall J (1989) Glossary of chimpanzee behaviors. Jane Goodall Institute, Tucson

Heymann RW (1998) Sex differences in olfactory communica- tion in a primate, the moustached tamarin, Saguinus mystax (Callitrichinae). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 43:37–45

Jacob S, McClintock MK, Zelano B, Ober C (2002) Paternally inherited HLA alleles are associated with women’s choice of male odor. Nat Genet 30:175–179

Kappeler PM (1990) Social status and scent-marking behaviour in Lemur catta. Anim Behav 40:774–776

Kappeler PM (1998) To whom it may concern: the transmission and function of chemical signals in Lemur catta. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 42:411–421

Matsumoto-Oda A, Oda R, Hayashi Y, Murakami H, Maeda N, Kumazaki K, Shimizu K, Matsuzawa T (2003) Vaginal fatty acids produced by chimpanzees during menstrual cycles. Folia Primatol 74:75–79

Nishida T (1983) Alpha status and agonistic alliance in wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii). Primates 24:318– 336

Nishida T (1990) A quarter century of research in the Mahale Mountains: an overview. In: Nishida T (ed) The chimpan- zees of the Mahale Mountains. University of Tokyo Press, Tokyo, pp 3–35

Nishida T (1997) Sexual behavior of adult male chimpanzees of the Mahale Mountains National Park, Tanzania. Primates 38:379–398

Nuishida T, Takasaki H, Takahata Y (1990) Demography and reproductive profiles. In: Nishida T (ed) The chimpanzees of the Mahale Mountains. University of Tokyo Press, Tokyo, pp 63–98

Nishida T, Kano T, Goodall J, McGrew WC, Nakamura M (1999) Ethogram and ethnography of Mahale chimpanzees. Anthropol Sci 107:141–188

Nishida T, Corp N, Hamai M, Hasegawa T, Hiraiwa-Hasegawa M, Hosaka K, Hunt KD, Itoh N, Kawanaka K, Matsumoto- Oda A, Mitani JC, Nakamura M, Norikoshi K, Sakamaki T, Tuner L, Uehara S, Zamma K (2003) Demography, female life history and reproductive profiles among the chimpan- zees of Mahale. Am J Primatol 59:99–121

Ober C, Weitkamp LR, Cox N, Dytch H, Kostyu D, Elias S (1997) HLA and mate choice in humans. Am J Hum Genet 61:497–504

Oppenheimer JR (1977) Communication in new world monkeys. In: Sebeok TE (ed) How animals communicate. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, pp 851–889

Palagi E, Telara S, Borgognini Tarli SM (2003) Sniffing behavior in Lemur catta: seasonality, sex and rank. Int J Primatol 24:335–350

de Waal FBM (1982) Chimpanzee politics. Jonathan Cape, London

Wallis J (1992) Socioenvironmental effects on timing of first postpartum cycles in chimpanzees. In: Nishida T, McGrew WC, Marler P (eds) Topics in primatology, vol 1, University of Tokyo Press, Tokyo, pp 119–130

Wallis J (1997) A survey of reproductive parameters in the free- ranging chimpanzees of Gombe National Park. J Reprod Fertil 109:297–307

Watts DP, Mitani JC (2001) Boundary patrols and intergroup encounters in wild chimpanzees. Behaviour 138:299–327 Wedekind C, Seebeck T, Bettens F, Paepke AJ (1995) MHC-

dependent mate preferences in humans. Proc Roy Soc Lond B 260:245–249

Wrangham RW (1977) Feeding behaviour of chimpanzees in Gombe National Park, Tanzania. In: Clutton-Brock TH (ed) Primate ecology: studies of feeding and ranging behaviour in lemurs, monkeys, and apes. Academic, London, pp 503–538