Toward a frame-semantic definition of sound-symbolic words: A collocational analysis of Japanese mimetics*

KIMI AKITA

Abstract

This article presents empirical evidence of the high referential specificity of sound-symbolic words, based on a FrameNet-aided analysis of collocational data of Japanese mimetics. The definition of mimetics, particularly their semantic definition, has been crosslinguistically the most challenging problem in the literature, and different researchers have used different adjectives (most notably, “vivid,” since Doke 1935) to describe their semantic peculiarity. The present study approaches this longstanding issue from a frame-semantic point of view combined with a quantitative method. It was found that mimetic manner adverbials generally form a frame-semantically restricted range of verbal/nominal collocations than non-mimetic ones. Each mimetic can thus be considered to evoke a highly specific frame, which elaborates the general frame evoked by its typical host predicate and contains a highly limited set of frame elements, which correlate and constrain one another. This conclusion serves as a unified account of

* Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the 27th Annual Meeting of the Japanese Cognitive Science Society held at Kobe University in September 2010 and some informal gatherings. I have greatly benefited from discussions with Michiko Asano, Mark Dingemanse, Mutsumi Imai, Sotaro Kita, Yo Matsumoto, Noburo Saji, and Kiyoko Toratani. I also thank two anonymous reviewers and an anonymous associate editor of Cognitive Linguistics for their detailed comments. My deepest gratitude goes to the members of Japanese Language Seminar in Berkeley—Charles Fillmore, Yoko Hasegawa, Albert Kong, Russell Lee-Goldman, Satoru Uchida, and Ikuko Yuasa—without whom I would not have even begun this study. Remaining inadequacies are, of course, my own. This study was partly supported by Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows (#21-2238) and a grant for Proyectos de Investigación Fundamental no Orientada (Tipo A) (#FEI2010-14903). This paper is dedicated to Koro (1993-2010), who would look back hearing its subtitle.

The author is now a lecturer at Osaka University. Correspondence address: Graduate School of Language and Culture, Osaka University. 1-8 Machikaneyama-cho, Toyonaka-shi, Osaka, 560-0043, Japan. E-mail: akitambo@gmail.com.

[SEMI-FINAL VERSION] Akita, Kimi. 2012. Toward a frame-semantic definition of sound-symbolic words: A collocational analysis of Japanese mimetics. Cognitive Linguistics 23(1): 67-90.

previously reported phenomena concerning mimetics, including the lack of hyponymy, the one-mimetic-per-clause restriction, and unparaphrasability. This study can be also viewed as a methodological proposal for the measurement of frame specificity, which supplements bottom-up linguistic tests.

Keywords: mimetics, adverbials, collocation, specificity, Frame Semantics, Japanese

1. Introduction

This article provides collocational evidence of the generally high referential specificity of sound-symbolic words (also called mimetics, ideophones, and expressives, depending on the target language area). I will compare the collocational properties of mimetic and non-mimetic manner adverbials in Japanese from the viewpoint of Frame Semantics (Fillmore 1982, 1985; Fillmore and Baker 2010; inter alia).

Like Basque, Korean, Quechua, and some Austro-Asiatic and Bantu languages, Japanese is known as a language with a particularly rich mimetic lexicon. Most dictionaries specializing in Japanese mimetics comprise over 1,500 conventional mimetic forms (Kakehi et al. 1996; among many others), and the number increases when unconventional and/or derived forms are included (see Ono 2007 for a dictionary containing many such mimetic entries). Japanese mimetics also have rich semantic variety. As illustrated in (1), they cover not only auditory but also visual/textural and bodily/emotional experiences.1

1 The abbreviations used in this paper are as follows: ACC = accusative; CAUS = causative; CL = classifier; CONJ = conjunctive; COP = copula; DAT = dative; GEN = genitive; MIM = mimetic; NEG

= negative; NML = nominalizer; NOM = nominative; NPST = nonpast; PASS = passive; POL = polite; POT = potential; PST = past; Q = geminate; QUOT = quotative; SFP = sentence-final particle; TOP = topic.

(1) a. Suzume-ga tyuntyun nai-te i-ru. (auditory, animate) sparrow-NOM MIM cry-CONJ be-NPST

‘Sparrows are crying tweet-tweet.’

b. Beru-ga rin-to nat-ta. (auditory, inanimate) bell-NOMMIM-QUOT sound-PST

‘The bell sounded jingle.’

c. Taiyoo-ga giragira kagayai-te i-ta. (visual) sun-NOM MIM shine-CONJ be-PST

‘The sun was shining glaringly.’

d. Akatyan-no hada-wa subesube-dat-ta. (tactile) baby-GEN skin-TOP MIM-COP-PST

‘The baby’s skin was smooth and dry.’

e. Atama-ga zukin-to si-ta. (bodily-sensational) head -NOM MIM-QUOT do-PST

‘[My] head throbbed.’

f. Haru-wa itumo ukiuki su-ru. (emotional) spring-TOP always MIM do-NPST

‘[I] feel buoyant in every spring.’

In Frame Semantics, the meanings of linguistic expressions are understood in terms of the whole background situation or knowledge (or “frame”) to which they pertain. Despite the fact that the meaning of mimetics is often conceived as “situational” (see Evans and Sasse 2007: 76), it has not been investigated in terms of frame evocation in either Japanese or other “mimetic/ideophonic languages.”2 In this study, I will take the first

2 Lu (2006) mentions the usefulness of Lakoff’s (1987) notion of Idealized Cognitive Model in semantic analyses of mimetics, and Hasada (2001) adopts a prototype-scenario-based semantic description of emotion mimetics in the Natural Semantic Metalanguage (Wierzbicka 1972).

step toward the frame semantics of mimetics by applying the notions of FrameNet, a frame-based lexical resource, to the semantic consideration of mimetic collocations in corpora.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 addresses the research question about the semantic definition of mimetics to be discussed in this paper. Section 3 presents a basic description of Frame Semantics and FrameNet as a useful but not fully equipped framework for semantic explorations in mimetics. This overview will point to the importance of a quantitative approach to mimetic semantics. Section 4 explains the method of the current collocation study, whose results will be reported in Section 5. The results will be discussed from a general perspective in Section 6, wherein I attempt to clarify the specific content of mimetic frames in relation to related phenomena reported for mimetics in previous studies. Section 7 concludes the article.

2. Research question

As many studies have discussed, the definition of mimetics has been the most controversial issue regarding mimetics. The most widely accepted definition is the one focusing on their formal—more precisely, morphophonological and phonotactic—peculiarities vis-à-vis “ordinary” lexical items (Samarin 1971; Johnson 1976; Childs 1994; Bartens 2000). For example, quite a few languages have a rich inventory of reduplicative mimetics (Doke 1935: 185), such as buubuu ‘grumbling’ in Japanese, bristabrista ‘walking very fast’ in Basque (Ibarretxe-Antuñano 2006: 12), and muktimukti ‘sniffing and sniffing’ in Pastaza Quechua (Nuckolls 1996: 64). Moreover, many languages have some marked phonotactic features unique to mimetics. Japanese mimetics’ preference of initial [p] (e.g., pikaQ ‘flashing’), which is otherwise prohibited However, both of these studies are still in their initial stage of development and do not fully clarify the necessity and advantage of their frameworks. The present frame-semantic investigation is expected to have some implications for the validity of these related approaches.

in native Japanese, is one such instance (Itô and Mester 1995; Hamano 1998: 6).

Meanwhile, the semantic definition of mimetics has been no more than intuitive labeling, as represented by Doke’s (1935: 118) description of Bantu ideophones as “a vivid representation of an idea in sound” (see also Cole 1955: 370). Here, I list some more such subjective labels used by previous researchers.

(2) “expressive/intense” (Samarin 1971), “eloquent” (Johnson 1976: 240), “explicit” (von Staden 1977: 195), “sensual/sensory” (Mphande 1992; Bradshaw 2006),

“specific/concrete” (Childs 1994: 188; Watson 2001), “affecto-imagistic, holistic” (Kita 1997), “vague, elusive” (Bartens 2000; Noss 2003; Tsujimura and Deguchi 2007), “dramaturgic” (Voeltz and Kilian-Hatz 2001: 5), “depictive” (Dingemanse 2011)

These adjectives are far from describing the semantic characteristic of mimetics in a linguistically satisfactory fashion. The present study therefore aims at an objective characterization of mimetic semantics based on a frame-semantic analysis of the collocational peculiarity of Japanese mimetics.

The collocation (or “selectional restriction”) of mimetics has been a frequently discussed topic. Quite a few studies report the strong verbal collocation of mimetics in many languages (Hirose 1981; Childs 1994; Kita 1997; Schaefer 2001; Watson 2001; Toratani 2010), and this phenomenon is sometimes described as a kind of “hyponymy” across lexical categories (Toratani 2007: 325). In other words, mimetics are viewed as providing further specification of the general information given by the verbs they modify. For example, mimetics for walking, such as tekuteku ‘walking with light steps’ and tobotobo ‘plodding’, add specific manner information like lightness and lethargy to the neutral manner of walking represented by the verb aruk- ‘walk’, which is a typical

collocate of these mimetics. A similar specification relationship can be pointed out for the Emai mimetic nyényényé ‘with a dash’ and its typical host láí ‘run’ (Schaefer 2001: 347). Despite, or due to, its self-evidence, this phenomenon has not received an empirical examination based on a quantitative method (for an exception, see Tamaoka et al. 2011, who investigate the verbal collocation of 28 Japanese mimetics for a different objective).

Therefore, the present large-scale corpus-based study of mimetic collocation is intended to make up for the gap in this research area. Based on the intuitive descriptions in (2), it will be reasonable to begin from the following general hypothesis for mimetic collocation.

(3) A hypothesis for the collocational property of mimetics:

If mimetics are “vivid” and “specific” in meaning, then their collocation should be highly restricted.

In what follows, this hypothesis will be examined based on a frame-semantic comparison of verbal and nominal collocations of mimetic and non-mimetic manner adverbials in Japanese.

3. Framework

3.1. Frame Semantics

In this section, I will outline the theoretical and methodological framework I use. Frame Semantics captures the meanings of linguistic signs in relation to the background situations (i.e., semantic frames) they evoke (Fillmore 1982; Fillmore and Petruck 2003; Fillmore and Baker 2010). The Berkeley FrameNet project is developing a corpus-based online lexical database whose annotation is crucially grounded in Frame Semantics.

Compared to this English version, FrameNets in German, Spanish, and Japanese are, unfortunately for the present study, much less developed (see Boas 2009 for some recent developments in FrameNets in different languages). An oft-cited example is the Commerce_sell frame (frame names are given in Courier fonts). This frame is evoked by “words describing basic commercial transactions involving a buyer and a seller exchanging money and goods, taking the perspective of the seller” (Berkeley FrameNet homepage, last accessed 6 April 2011). The words include not only verbs such as auction, retail, sell, and vend but also nouns such as auction, retailer, sale, and vendor. This cross-part-of-speech grouping is one of the important features of Frame Semantics (Petruck 1996), and it will play a critical role in the current study as well. Each frame is posited with a set of fine-grained semantic roles, called “frame elements” (FEs). FEs are divided into core FEs (cFEs) and non-core FEs (nFEs) depending on their centrality/peripheralness for the frame. For example, Commerce_sell has BUYER, GOODS, and SELLER as its cFEs and MANNER, MEANS, and MONEY as its nFEs (FEs are indicated by SMALL CAPITALS).

Frames are related to one another via eight kinds of “frame-frame relations” in the current version of FrameNet. These relations allow frames to form a network. For example, because selling is a kind of giving, the Commerce_sell frame is in an

“Inheritance” relation to the Giving frame. Moreover, because selling takes the seller’s perspective on a commercial transaction, which can be instead perspectivized from the buyer, Commerce_sell is in a “Perspective on” relation to Commerce_goods-transfer. Furthermore, because the act of selling is used in wholesale and export, a “Using” relation is posited between Commerce_sell and Carry_goods or Exporting. The other frame-frame relations are “Subframe” for part-whole relations, “Precedence” for relations of temporal order, “Inchoative/Causative of” for causation relations, and “See also” for direct relations between otherwise

indirectly related frames. These relations will be utilized to examine the frame-semantic relations between collocates in our corpora.

3.2. Specificity of frames

As suggested in the Introduction, Frame Semantics seems to be an appropriate framework for mimetic semantics due to its situational basis. However, the current version of FrameNet does not offer an analytical tool that is directly applicable to the present study. There are two major reasons for this absence.

First, FrameNet has mainly targeted verbs, nouns, and adjectives, and we can find only a few adverb entries (e.g., slowly) in it. This may be because of the syntactic optionality and peripheralness of adverbs and the presumable complexity of their frames. Another likely reason is the fact that a majority of sounds and manners depicted by Japanese mimetics are encoded in verbs in English (see Hirose 1981; Talmy 2000).

Second, there is no particular measure for the specificity or complexity of frames, which we need for our quantitative investigation of mimetic collocation. In fact, FrameNet does not make fine distinctions among specific kinds of eventualities that mimetics represent, for they do not make noteworthy difference with respect to FEs. For instance, in FrameNet, manners of motion that would be represented by mimetics, such as sutasuta ‘walking briskly’ and tyorotyoro ‘scuttling around’, evoke the Self_motion frame, in which “[t]he SELF_MOVER, a living being, moves under its own power in a directed fashion, i.e., along what could be described as a PATH, with no separate vehicle” (FrameNet homepage, last accessed 10 April 2011). In a similar vein, various sorts of sound emissions that would be mimicked by onomatopoeic mimetics (e.g., gatyan ‘smash’, kasakasa ‘rustle’) evoke Make_noise or Motion_noise. All kinds of pain represented by mimetics (e.g., zukin ‘throbbing’, muzumuzu ‘itching’) evoke Perception_body.

Concerning this second point, Boas (2006, 2008) proposes the application of Snell-Hornby’s (1983) notion of “verb-descriptivity” to the measurement of frame specificity. Boas’ aim is to identify the syntactically relevant parts of verb meaning and to obtain more elaborate verb classes than generally supposed.3 To demonstrate that detailed semantic specification (i.e., verb-descriptivity) may differ even among verbs evoking the same frame, he presents a case study with a set of manner-of-motion verbs in English. He observes how many “modificants” (i.e., modifying components of meaning) each verb contains in addition to its semantic core, called “act-nucleus”—the mover’s motion from Source to Goal via Path in this case (see also Slobin 1997). Practically, he attempts to count modificants of each manner-of-motion verb by examining the (in)compatibility of each with certain manner expressions. For example, the verb walk can occur with a wide range of adverbials, including in a daze, springily, and quickly and secretly. This fact leads him to conclude that walk is a manner-of-motion verb with low verb-descriptivity. On the other hand, the occurrence of bustle is by far more restricted, as illustrated by *Kim bustled calmly out of the house (Boas 2008: 35). Based on this, Boas qualifies bustle as a highly descriptive verb, which contains very specific manner information, such as energeticity and hurriedness.

This approach seems to be applicable, at least to some extent, to mimetics as well. For example, the following contrast shows that sekaseka, but not tekuteku, has a semantic specification of the mover’s emotional state as “restless.”

(4) Yui-wa otitui-te {*sekaseka/ tekuteku} arui-te it-ta. Y.-TOP get.calm-CONJ MIM MIM walk-CONJ go-PST

‘Yui went walking calmly {*restlessly/with light steps}.’

3 The syntactic relevance of fine-grained verb meaning is also discussed from the perspective of Construction Grammar in Boas (2003), Croft (2003), and Iwata (2008). I am grateful to an anonymous reviewer for directing me to these notable investigations.

However, we can point out at least two methodological weak points in this approach. First, this is potentially an endless task. We might detect particular semantic specifications of a verb or mimetic by testing its particular cooccurrence possibilities. However, we can say nothing about what we have not tested yet. Furthermore, it is not clear how many such tests are needed for each word to make a reliable judgment about the frame specificity of each. This last point is especially relevant to mimetics, whose semantics, as will be discussed later, can nearly correspond to one situation, rather than its components, such as manner, emotional state, and event time. Thus, it would be unrealistic to aim at an exhaustive examination in this direction.

Second, it is very common that linguistic tests of this kind result in unclear judgments with one or more question marks. For example, the mild ungrammaticality of (5) suggests that the mimetic tekuteku ‘walking with light steps’ has some implications about the psychological state of the mover, which would not be as explicit as an entailment or semantic specification.

(5) Yui-wa {?huange-ni/ ??okori-nagara} tekuteku arui-te it-ta. (cf. (4)) Y.-TOP anxious-COP get.angry-while MIM walk-CONJ go-PST

‘Yui went walking {?anxiously/??angrily}.’

Given that our frame-semantic knowledge is not something that can be clearly defined with a set of truth values, it should involve implications and connotations such as this as well.

In contrast, the corpus-based approach taken in the present study is free from these two potential problems. Specifically, our quantitative method is exhaustive in the sense that it targets the entire dataset all at once. This approach is also compatible with the

gradable data, which is captured in terms of frequency or collocability. In this regard, the present study can be described as a methodological proposal not merely for the research of mimetics but also for the theory of Frame Semantics. More concretely, I will statistically analyze the frame evocation of verbal and nominal collocates of mimetics, whose descriptions are available in FrameNet, to evaluate the frame specificity of mimetics themselves. This is, indeed, an indirect method of analysis but certainly the most direct quantitative approach currently available.

4. Method

In this section, I give a detailed description of the quantitative method adopted in this study. I used two corpora—the Aozora Bunko Corpus (ABC) and the Meidai Kaiwa Corpus (MKC)—both of which are linked to Chakoshi, which is an online collocator based on a widely used Japanese morpheme analyzer, called Chasen. The ABC (actually its subpart) consists of 8,370,720 morphemes from 703 out-of-copyright literary works written in Modern Japanese. The MKC consists of 2,318,134 morphemes from a 100-hour recording of two to four people’s informal conversations (161 females, 37 males). Tamaoka et al.’s (2011) corpus-based study found that novels allow innovative collocations of mimetics and verbs to a greater extent than newspapers. This seems to hold true for mimetic collocation in general (including, for example, nominal collocation), and this kind of creativity can be expected for informal conversations as well (see Schourup 1993). Therefore, collocations that retain their strength even in the two corpora should be regarded as particularly significant.

I searched mimetic and non-mimetic manner adverbials in these corpora. I limited myself to 518 reduplicative mimetics with a bimoraic root (e.g., pukapuka ‘floating’), which occupy the largest portion of the Japanese mimetic lexicon, from Kakehi et al.’s (1996) two-volume dictionary. One hundred and sixty-four non-mimetic manner

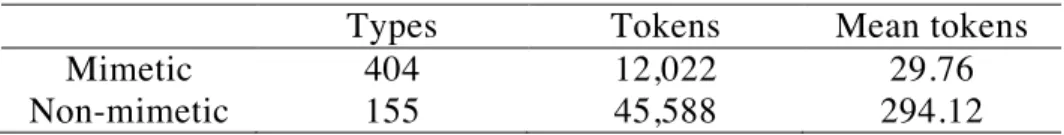

adverbials without mimetic origin (e.g., issyookenmei ‘hard’) were collected from Nitta’s (2002) list of Japanese adverbials. Most of them were not inherently adverbs but rather compounds (e.g., tikara-ippai [power-plenty] ‘forcefully’), or conjunctive forms of verbs and adjectives (e.g., isoi-de [hurry-CONJ] ‘hurriedly’), and phrases (e.g., kawai-ta koe-de [get.dry-PST voice-in] ‘in a husky voice’). All orthographical possibilities of these expressions were considered. Table 1 gives their total type and token frequencies in the two corpora. Strikingly, individual mimetic adverbials are much less frequent than non-mimetic ones but together contribute to the sum of more than 12,000 occurrences. The restricted use of each mimetic is already suggestive of its frame-semantic specificity.

Table 1. Frequency of adverbials in the corpora

Types Tokens Mean tokens

Mimetic 404 12,022 29.76

Non-mimetic 155 45,588 294.12

Based on Shibasaki’s (2009) finding that Japanese manner adverbials typically directly precede their host verb, five morphemes before each adverbial and three morphemes after it were included in the search range.4 All orthographical and conjugational possibilities were considered for collocates. Following Church et al. (1991), only collocations whose t-value was 2.0 or higher were considered to be significant. Significant adjectival collocations were excluded because they only amounted to 2% of the dataset. Functional elements (e.g., -kara ‘from’, -to (QUOT))

4 Toratani (2006) observes that the occurrence of the optional quotative particle -to after mimetics enhances their collocability: mimetics without the quotative marking are subject to a stronger collocational restriction. However, this factor was not considered throughout the present investigation. Nevertheless, significant collocations can be assumed to survive regardless of the presence of -to.

found in a significant collocation were excluded due to their semantic lightness.5

All 410 significant collocates obtained were coded in terms of frame evocation by referring to English FrameNet. Twenty percent of the collocates were checked by another frame semanticist, and the correspondence rate was 98.76%. More crucially, the verbal and nominal collocates of mimetic and non-mimetic adverbials were compared with respect to their frame-semantic consistency. I analyzed the frame-semantic relationship between collocates of adverbials with more than one significant collocate. The top two verbal collocates (V1, V2) and the top two nominal collocates (N1, N2) at the most were targeted for one adverbial. (This is because most mimetic adverbs were found with only zero to two significant verbal/nominal collocates, and many non-mimetic adverbials were found with more than four verbal/nominal collocates (see Figure 1 below).) Accordingly, six pairs of collocates (i.e., V1-V2, V1-N1, V1-N2, V2-N1, V2-N2, N1-N2) at the most were considered for one adverbial. Each pair of collocates was classified into one of the following five categories, again based on English FrameNet.

(6) Frame-semantic relationships between collocates: a. Identical:

Two collocates evoke the same frame (at FrameNet’s specification level). b. Related:

Two collocates evoke related frames (see Section 3). c. cFE instantiating:

One collocate instantiates a cFE of the frame evoked by the other collocate.

5 The t-value for a collocation of the morphemes X and Y is calculated by the following formula:

t = freq. of X-Y colloc. − freq. of X × freq. of Y ÷ number of morphemes in corpus √freq. of X-Y colloc.

d. nFE instantiating:

One collocate instantiates an nFE of the frame evoked by the other collocate. e. Unrelated:

Two collocates have no evident frame-semantic relation to each other.

Extending from our starting hypothesis in (3), we can now formulate a specific prediction, such as (7).

(7) A prediction about the collocational property of mimetics:

If mimetics have high referential specificity, then their collocates should tend to be semantically related to one another—namely, classified into (6a-d).

Needless to say, the present cross-categorial, as well as cross-positional, consideration is a distinguished advantage of our frame-semantic standpoint.

5. Results

5.1. The number of significant collocates

The results were not only consistent with the prediction in (7) but also suggestive of some other fundamental characteristics of mimetic semantics. First, mimetic as well as non-mimetic adverbials showed nominal collocations in addition to verbal ones, which was somewhat surprising, based on previous observations. For example, as cited in (8), the mimetic adverbs musyamusya ‘eating carelessly with one’s mouth full’ and wakuwaku ‘exhilaratedly’ were frequently found with the ingestion verb kuw- ‘eat’ and the body-part noun mune ‘chest’, respectively. (The instances presented below are all from the ABC, from which a large part of the present data was obtained. Adverbials are given in boldface, their collocates underlined, and their collocational strength in [square

brackets].)

(8) Mimetic adverbs: a. Verbal collocation:

Syuzin-wa… muzoosa-ni manzyuu-o wat-te, musyamusya owner-TOP random-COP bean.paste.bun-ACC divide-CONJ MIM

kui-hazime-ta. [t = 3.31] eat-start-PST

‘The owner divided a bean-paste bun and began to eat [it] carelessly with [his] mouth full.’

(Soseki Natsume, Mon [The gate]) b. Nominal collocation:

Sadako-no sum-u onazi toti-ni kaet-te ki-ta-to

S.-GEN live-NPST same land-DAT return-CONJ come-PST-QUOT

omo-u-dake-de-mo moo mune-wa wakuwaku si-ta. [t = 3.29] think-NPST-only-by-even already chest-TOP MIM do-PST

‘Even thinking that [I]’ve come back to the same land as Sadako lives, [I] already felt [my] heart exhilarated.’

(Takeo Arishima, Aru onna [A certain woman])

Similarly, in (9), the non-mimetic manner adverbs asibaya-ni ‘quickly’ and sawayaka-ni

‘refreshingly’ form a significant collocation with the verb aruk- ‘walk’ and the noun bisyoo ‘smile’, respectively.

(9) Non-mimetic adverbials: a. Verbal collocation:

Hiroko-wa… imooto-no koibito-no mae-e kokoromoti asibaya-ni H.-TOP younger.sister-GEN lover-GEN front-to somewhat quick-COP

arui-te it-ta. [t = 3.46] walk-CONJ go-PST

‘Hiroko went walking somewhat quickly to front of [her] younger sister’s boyfriend.’

(Ryunosuke Akutagawa, Haru [Spring]) b. Nominal collocation:

… hurimui-ta Oran-no utukusi-i nakigao-e, sawayaka-ni turn.around-PST O.-GEN beautiful-NPST tearful.face-to refreshing-COP

bisyoo-o hukun-da meizin-no koe-ga sosog-are-masi-ta. [t = 2.82] smile-ACC contain-PST expert-GEN voice-NOM pour-PASS-POL-PST

‘…on the beautiful tearful face of Oran, who looked back, the expert’s voice containing a smile was poured refreshingly.’

(Mitsuzo Sasaki, Umon torimono-tyoo [Detective Umon’s diary])

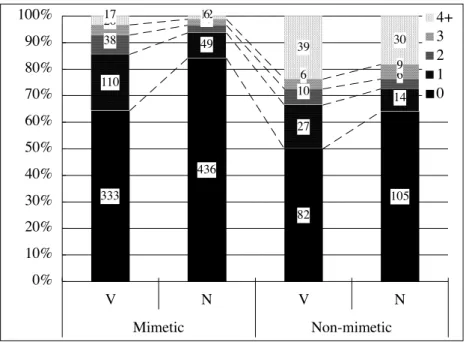

Figure 1 summarizes the overall distribution of mimetic and non-mimetic adverbials by the number of their significant collocates. A significant correlation was obtained between the token frequency of each adverbial (see Table 1 above for the entire trend) and the number of its significant collocates in both mimetic (rs = .86 (V), .70 (N), ps

< .001) and non-mimetic collocations (rs = .56 (V), .51 (N), ps < .001). This suggests that the overwhelmingly greater number of significant collocates of non-mimetic adverbials is ascribable to their greater token frequency.

333

436

82

105 110

49

27

14 38

15

10

6

20 12

6

9

17 6

39 30

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

V N V N

Mimetic Non-mimetic

4+ 3 2 1 0

Figure 1. The number of significant collocates

What should be noted here is that mimetic adverbs turned out to have significantly more verbal collocates than nominal ones (Ms = 0.68 (V), 0.28 (N); t (401) = 6.29, p < .001), whereas non-mimetic adverbials did not show such a contrast (Ms = 3.35 (V), 2.60 (N); t (282) = 1.03, p = .30). For instance, the mimetic adverb suyasuya ‘(sleep) peacefully’ was found to form a significant collocation with three verbs (i.e., nemur- ‘sleep’ [t = 4.36], ne- ‘sleep, lie down’ [t = 2.62], neir- ‘sleep in’ [t = 2.24]) but with only one noun (i.e., neiki ‘sleeper’s breathing’). Meanwhile, it was observed that the non-mimetic adverbial surudoku ‘sharply’ significantly collocates with five verbs (e.g., sakeb- ‘shout’ [t = 3.15], hikar- ‘shine’ [t = 2.81], iw- ‘say’ [t = 2.07]) and five nouns (e.g., me ‘eye’ [t

= 6.37], meizin ‘expert’ [t = 3.29], sinkei ‘nerve’ [t = 2.21]). This result is reminiscent of the idea of “cross-categorial hyponymy,” which I briefly addressed in Section 2. We can interpret that the noticeable semantic link between certain mimetics and verbs allowed them to form strong collocations.6 This point will be further developed from a

6 The present result is also consistent with the traditional idea that mimetics are basically

“eventive/dynamic” in nature (Kunene 1965; Samarin 1971; Kita 1997; Hamano 1998: 12). This semantic component of mimetics has recently been recognized as a trigger for their

frame-semantic point of view in Section 6.1 below.

5.2. Frame-semantic consistency of collocates

I will proceed to analyze the collocation data with respect to the frame-semantic consistency of collocates. The analysis begins with actual instances of the five types of frame-semantic relationships between mimetic collocates, as defined in (6) above.

First, both maw- ‘dance’ and tob- ‘fly’ in (10), which were identified as significant collocates of the mimetic adverb hirahira ‘flutteringly’, evoke the Motion frame. Therefore, this pair of verbs can be concluded to be frame-semantically identical collocates.

(10) Identical:

a. Soko-ni-wa nogiku-ya kikyoo-ga saki-midare-te, there-DAT-TOP wild.chrysanthemum bellflower-NOM

bloom-be.disarranged-CONJ

aki-no tyoo-ga hirahira-to mat-te i-ta. [t = 2.64] fall-GEN butterfly-NOMMIM-QUOT dance-CONJ be-PST

‘In the place, wild chrysanthemums and bellflowers were blooming all over, and autumnal butterflies were dancing flutteringly.’

(Kido Okamoto, Tamamo-no-Mae [Tamamo-no-Mae]) b. Soko-e, hontooni kaze-to tomoni iti-yoo-no tegami-ga, kare-no

there-to really wind-with together 1-CL-GEN letter-NOM him-GEN

sound-symbolic facilitation of children’s verb acquisition (Imai et al. 2008). An anonymous reviewer pointed out that this view would expect mimetic adverbs to have many eventive nominal collocates as well. In the current study, however, only one event noun was obtained as a significant collocate of a mimetic (i.e., inemuri ‘dozing’ for the mimetic utouto ‘dozing’). This fact might suggest that the “hyponymy” thesis is superior to the eventivity thesis in the discussion of mimetic semantics, despite their considerable overlap in conception (see Section 6.1).

temoto-e hirahira ton-de ki-ta. [t = 2.22] at.hand-to MIM fly-CONJ come-PST

‘To the place, a letter came flying flutteringly to [his] hands literally in the wind.’ (Osamu Dazai, Sarumen-kanzya [Monkey-faced youth])

In (11a), the mimetic adverb sutasuta ‘(walking) briskly’ modifies the verb aruk-

‘walk’, which evokes Self_motion. In (11b), the same mimetic modifies the verb ik-

‘go’, which evokes the general Motion frame. The former frame is a kind of the latter. Hence, an Inheritance relation holds here.

(11) Related:

a. Kanozyo-wa… wazukani ik-ken-hodo-no kyori-o oi-te, she-TOP only 1-CL-about-GEN distance-ACC place-CONJ

otoko-no-yoo-ni sutasuta-to arui-te ku-ru. [t = 3.99] man-GEN-like-COPMIM-QUOT walk-CONJ come-NPST

‘She comes walking briskly like a man, keeping a distance of only one ken (≒ 1.82m) or so [from me].’

(Kido Okamoto, Hansiti torimono-tyoo [Detective Hanshichi’s diary]) b. … sutasuta-to rooka-o ik-u-no-o, mamakko-no-yoo-na metuki-de MIM-QUOT hallway-ACC go-NPST-NML-ACC stepchild-GEN-like-COP look-with mi-nagara… [t = 2.62]

look-while

‘…seeing [her] go briskly in the hallway with a stepchild-like look…’

(Kyoka Izumi, Mayu-kakusi-no rei [How beautiful without eyebrows])

In (12a) and (12b), the mimetic adverb kotukotu ‘taptap’ collocates with the verb

tatak- ‘hit’ and the noun tobira ‘door’, respectively. The noun instantiates a cFE (i.e., IMPACTEE) of the Impact frame, which is evoked by the verb.

(12) cFE instantiating:

a. Moo hitugi-no huta-o, kotukotu-to tatak-u mono-ga already coffin-GEN lid-ACC MIM-QUOT hit-NPST person-NOM

at-te-mo i-i-hazu-da [t = 3.16] be-CONJ-even good-NPST-must-COP

‘It’s about time someone knocked taptap on the lid of [my] coffin’

(Juza Unno, Sennengo-no sekai [The world in a thousand years]) b. Zimusyo-no tobira-o kotukotu tatak-u mono-ga ari-mas-u. [t = 3.00]

office-GEN door-ACCMIM hit-NPST person-NOM be-POL-NPST

‘Someone is knocking taptap on the door of the office.’

(Kenji Miyazawa, Neko-no zimusyo [The cat’s office])

In (13), the mimetic adverb otioti ‘(stay) in peace’ cooccurs with the verb ne- ‘sleep’ and the noun yoru ‘night’. The verb evokes Sleep, whose nFE TIME (of event) is instantiated by the noun.

(13) nFE instantiating:

a. Do-o kosi-ta hiroo-no tame-ni, Gen-mo otioti degree-ACC exceed-PST fatigue-GEN reason-COP G.-too MIM

ne-rare-mas-en. [t = 3.46] sleep-POT-POL-NEG

‘Due to [his] excessive fatigue, Gen cannot sleep in peace.’

(Toson Shimazaki, Wara-zoori [Straw sandals])

b. “Huku-nanka, konogoro sikar-are-doosi-nanode ki-ni yan-de H.-at.all these.days scold-PASS-keeping-due.to feeling-DAT care-CONJ

yoru-mo otioti yasum-e-nai-rasi-i-no.” [t = 2.44] night-even MIM rest-POT-NEG-likely-NPST-SFP

‘“Because Huku is being scolded all the time these days, [she] seems to be worried and unable to sleep in peace even at night.”’

(Tsuseko Yada, Titi [Father])

Finally, the mimetic adverb syobosyobo ‘drizzlingly, blearily’ in (14) forms a significant collocation with the nouns ame ‘rain’ and me ‘eye’. Ame evokes Precipitation, whereas me evokes Observable_body_parts. It is unlikely that the two frames, as well as the two nouns, are related in a natural way.

(14) Unrelated:

a. Akuruhi-mo aki-rasi-i inki-na ame-ga syobosyobo hut-te next.day-too fall-like-NPST gloomy-COP rain-NOMMIM fall-CONJ

i-ta-ga… [t = 2.82] be-PST-but

‘An autumnal gloomy rain was falling drizzlingly the next day, too, but…’

(Kido Okamoto, Hansiti torimono-tyoo [Detective Hanshichi’s diary]) b. … teisai-no waru-soo-na kao-de me-o syobosyobo s-ase-te

appearance-GEN bad-likely-COP face-with eye-ACC MIM do-CAUS-CONJ

i-ru Ryuukiti-ni hotohoto doozyoo si-ta… [t = 4.89] be-NPST R.-DAT completely sympathy do-PST

‘…[I] completely sympathized with Ryukichi, who was blinking [his] eyes with an embarrassed face…’

(Sakunosuke Oda, Meoto-zenzai [The pair of zenzai])

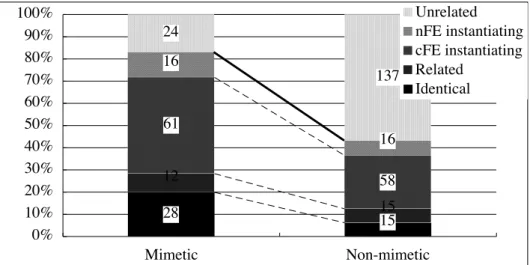

As I explained in Section 4, all possible pairs of collocates were analyzed in this manner. Figure 2 summarizes the results. As is obvious, more than 80% of mimetic collocate pairs were related in one way or another, whereas more than half of non-mimetic collocate pairs were not. A chi-square test yielded a significant difference between the two (χ2 (1) = 57.86, p < .001). Notably, about one-fifth of collocate pairs for our mimetic adverbs turned out to evoke identical frames, whereas such cases are less than 10% in non-mimetic adverbials.

28 15

12

15 61

58 16

16 24

137

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

Mimetic Non-mimetic

Unrelated nFE instantiating cFE instantiating Related

Identical

Figure 2. Frame-semantic relationships of collocates

The present results are consistent with our prediction in (7) and support the high frame

specificity of mimetics.7

Before drawing the final conclusion, however, we need to refute another possible interpretation of the results. A distributional contrast such as Figure 2 would also occur under the condition in which a great number of non-mimetic adverbials were polysemous. Different meanings are associated with different frames. Therefore, the frequent occurrence of polysemous words can result in many unrelated frames. It is true that, as in every mimetic dictionary, many mimetics also have multiple meanings: for example, the mimetic syobosyobo refers to the drizzling manner of raining, as in (14a), and the bleariness of eyes, as in (14b). Nevertheless, we cannot deny the possibility that the use of polysemous mimetic adverbs was strongly skewed toward one of their meanings in our corpora.

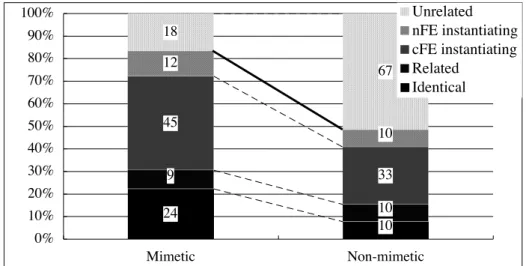

For this reason, I performed the same statistical procedures only with monosemous adverbials (e.g., tekuteku ‘with light steps’, toototu-ni ‘abruptly’). Kakehi et al. (1996) and some other dictionaries were consulted to determine the number of meanings of each adverbial. As a result, as shown in Figure 3, the sharp contrast between mimetic and non-mimetic adverbials was successfully retained (χ2 (1) = 32.23, p < .001). Thus, we can now convincingly conclude that the present results support the frame-semantic specificity of mimetics.8

7 It should be noted that the present study by no means intends to argue that all mimetics are equally specific in meaning. It is a general agreement that “mimeticity” is dependent on the degree of conventionalization. This is exemplified by some quasi-regular (or quasi-mimetic) reduplicative adverbs (e.g., botiboti ‘soon’, tyokutyoku ‘frequently’). Interestingly, these reduplicatives turned out to have no single significant collocate in the present corpora. Quasi-regular adverbs are more common in some other morphophonological types of mimetics (e.g., yuQkuri ‘slowly’, ziQ-to ‘patiently’) (see Toratani 2007: 316-317, 2010). Some studies also discuss the correlation between mimeticity and iconicity (see Akita 2009).

8 An anonymous reviewer suggested that the frame-semantic specificity of mimetics would be clarified by confirming the semantic consistency of the full range of verbs and nouns each mimetic can occur with. I tried this with some mimetics. As a result, even their insignificant collocates (those with t < 2.0) showed some semantic coherence, often with lesser clarity. For example, the monosemous mimetic hirahira ‘flutteringly’ was found with tyoo ‘butterfly’ [t = 1.99], kaze ‘wind’ [t = 1.94], and ugok- ‘move’ [t = 1.73], as well as the motion verbs in (10). These weak collocates evoke or participate in the Motion frame.

24 10 9

10 45

33 12

10 18

67

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

Mimetic Non-mimetic Unrelated nFE instantiating cFE instantiating Related

Identical

Figure 3. Frame-semantic relationships of collocates of monosemous adverbials

6. General discussion 6.1. Mimetic frames

Based on the findings in the previous section, we can reason that mimetic adverbials tend to evoke more specific frames than non-mimetic ones, and these mimetic frames normally involve a restricted kind of dynamic eventuality and FEs. We may then investigate whether it is possible to develop a more precise image of mimetic frames based on the current study.

One possible addition to the delineation of mimetic frames again derives from the notion of cross-categorial hyponymy mentioned in Section 2. From the frame-semantic point of view, this relationship can be captured as Inheritance at the frame-semantic level rather than the lexical-categorial level. This frame-frame relation holds between the frame of a mimetic and that of its collocate verb, not between these two lexical items. This suggests that the mimetic frame is a further specified version of the verb frame. For example, the frame evoked by the mimetic hirahira ‘flutteringly’ in (10) can be understood as an elaboration of the Motion frame, which its collocate verbs evoke (this verb frame may correspond to Boas’/Snell-Hornby’s “act-nucleus”). The mimetic frame

should contain information about, for example, the specific kind of object in motion (i.e., a thin, light object such as a petal, a feather, or a butterfly) and the specific manner (i.e., a fluttering manner caused by the combination of gravity and air resistance on the thin, light object). There is an obvious causal relationship between the object specification and the manner specification. I would like to emphasize that this is the very nature of highly specific frames. The closer a frame is to an individual real-world situation, the more strongly its FEs correlate with and restrict one another. In fact, FEs of a higher-order frame, such as SELF_MOVER and his/her MANNER of Self_motion, do not show such a strong mutual restriction. The causal relationship among FEs is a likely source of the observed restriction on nominal, as well as verbal, collocates of some mimetics.

6.2. Related phenomena

The idea of frame-semantic specificity of mimetics also has implications for a better understanding of some previous descriptions. It seems to serve as a unified account of five mimetic-related phenomena, which have mostly been pointed out in separate places, often in separate languages.

First, Watson (2001: 393), Bodomo (2006: 204), and Kita (2008: 26) discuss the absence of hyponymy within a mimetic category. It is very likely that many mimetics instead cluster together to form a horizontal relationship to one another (see also Tamaoka et al. 2011). For example, mimetics for walking, such as burabura ‘strolling’, sutasuta ‘walking briskly’, tekuteku ‘walking with light steps’, tobotobo ‘plodding’, tokotoko ‘walking lightly in a cute way’, yoroyoro ‘staggering’, yotayota ‘tottering’, and yotiyoti ‘toddling’, together make fine distinctions in this particular region of semantics, all standing in a pseudo-hyponymic relationship to their common collocate verb aruk-

‘walk’ (see Slobin 1997; Schaefer 2001; Ibarretxe-Antuñano 2006; Toratani 2007).9 Stating in favor of our frame-semantic view, all of these mimetics evoke too specific a frame to have a lexical hyponym below them.

Second, Watson (2001: 393), Bodomo (2006: 204), and Toratani (2007: 316-317) point out that, unlike regular lexical items, mimetics are unlikely to be modified (e.g.,

*totemo kiraQ-to hikar- ‘shine very twinklingly’, *yori yotiyoti aruk- ‘walk more toddlingly’). In our frame-semantic view, this can be interpreted as a phenomenon in which the semantic specificity of mimetics prevents their meanings from further specification.

Third, Kita (1997: 405) argues that in Japanese, “[o]nly one mimetic adverbial is usually allowed in a clause.” This is illustrated by (15a), wherein the two mimetics musyamusya ‘eating carelessly with one’s mouth full’ and pakupaku ‘eating vigorously’ fail to cooccur in one clause. Note that he also points out that mimetics do allow for semantic overlap with a non-mimetic manner expression, such as haya-aruki ‘hurried walking’ for the mimetic sutasuta ‘walking briskly’ in (15b).

(15) a. *Taroo-wa manzyuu-o musyamusya-to pakupaku-to tabe-ta. T.-TOP bean.paste.bun-ACC MIM-QUOT MIM-QUOT eat-PST

‘Taro vigorously and carelessly ate bean-paste buns with [his] mouth full.’ (corrected from Kita 1997: 405)

9 Interestingly, manner-of-motion mimetics including these showed a particularly strong preference for verbal collocations. Together with the discussion in Section 6.1, this result suggests that this frequently cited class of mimetics instantiates the prototype of mimetics (Hirose 1981; Ibarretxe-Antuñano 2006).

b. Taroo-wa sutasuta-to haya-aruki-o si-ta. T.-TOP MIM-QUOT haste-walk-ACC do-PST

‘Taro walked hurriedly.’

(Kita 1997: 388)

Our frame-based approach allows us to ascribe this restriction to the contradiction made otherwise, due to the high referential specificity of each of the two mimetics in (15a). Two distinctive situations cannot coexist at the same point in time and place in the real world.

Fourth, Tamori (1988) discusses the frequent omissibility of predicates in sentences with a mimetic in highly colloquial discourse, newspaper headings, and advertisements. For example, the sentence in (16) ends with the mimetic geragera ‘guffawing’, which should be followed by the verb waraw- ‘laugh’ in normal discourse.

(16) Piero-no kokkei-na sigusa-ni kansyuu-wa issei-ni geragera. pierrot-GEN funny-COP behavior-DAT audience-TOP all.together-COPMIM

‘The entire audience laughed loudly at the clown’s funny actions.’

(Tamori 1988: 105)

Based on the discussion in the previous subsection, the Inheritance relation between mimetic and verb frames should reside in the absence of a predicate in this case. Each mimetic (geragera in the present case) evokes a frame sufficiently specific to cover the frame of its typical verbal collocate (waraw- in the present case). As a consequence, the verb frame is recoverable from the mimetic by means of Inheritance, which is part of our frame-semantic (or “encyclopedic”) knowledge rather than our purely lexical knowledge. Fifth, Fortune (1962: 43) and Diffloth (1972: 441) point out the unparaphrasability of

mimetics. According to Diffloth (1972: 441), “[i]n trying to paraphrase an ideophone with ordinary words of the same language, we find that several sentences are often needed, and even then, the paraphrase is not wholly satisfactory.” In principle, we need multiple words to evoke a specific or complex frame. The reported difficulty of successful paraphrasing of mimetics can therefore be considered an index of the extremely high specificity of mimetic frames.

The idea of the frame-semantic specificity of mimetics thus provides an unprecedented natural, consistent account of various aspects of the lexical and grammatical components of mimetics. In other words, these diverse phenomena can be regarded as further evidence of the exceptional specificity of mimetic frames.

7. Conclusion

In this paper, I have discussed the high frame-semantic specificity of mimetics, based on a quantitative and qualitative comparison of mimetic and non-mimetic manner adverbials in Japanese. It was found that mimetics are more likely to form significant collocations with verbs, although they do have significant nominal collocations as well. This result led me to argue that mimetic frames are generally an elaboration of a verb frame that reflects a real-world situation more directly.

The present findings allow us to presume that the eventuality depiction of mimetics is

“mediated” by a frame. They do not depict a situation but rather evoke a frame that mirrors the situation with high faithfulness. I consider this a minor but crucial paraphrase. It enables us to treat mimetics—seemingly “peculiar” linguistic items—in essentially the same fashion as non-mimetic “regular” items: they only differ in the specificity of frames they evoke. This parallelism accounts for the well-known fact that even this inherently iconic word class is subject to a certain degree of arbitrariness (Hinton et al. 1994). Frames, even mimetic frames, cannot be real-world situations themselves.

To sum up, the current study provided some empirical data intended to replace and substantiate the traditional subjective semantic definitions of mimetics. This approach also has some theoretical/methodological implications, with its proposal of collocation-based measurement of the specificity of frames, which can supplement bottom-up linguistic tests—for English manner-of-motion verbs, for example. This is a promising direction, in that collocational information has already been partially taken into account in FrameNet (Ruppenhofer et al. 2002). Explorations in frame specificity will lead us to clarify the vertical (and perhaps horizontal) structure of our frame-semantic network of knowledge. Future studies will include a closer examination of individual mimetic collocations (e.g., in search of syntactically relevant aspects of mimetic semantics; see fn. 3), similar collocational investigations into other types of mimetics (e.g., nonreduplicative, resultative) and other lexical categories (e.g., verbs, nouns, and adjectives), and more direct approaches to the frame semantics of mimetics (e.g., a lexical association task).

References

Akita, Kimi. 2009. A Grammar of Sound-Symbolic Words in Japanese: Theoretical Approaches to Iconic and Lexical Properties of Mimetics. Ph.D. dissertation, Kobe University.

Bartens, Angela. 2000. Ideophones and Sound Symbolism in Atlantic Creoles. Helsinki: Finnish Academy of Sciences and Letters.

Boas, Hans Christian. 2003. A Constructional Approach to Resultatives. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.

Boas, Hans Christian. 2006. A frame-semantic approach to identifying syntactically relevant elements of meaning. In Petra C. Steiner, Hans Christian Boas, and Stefan J. Schierholz, eds., Contrastive Studies and Valency: Studies in honor of Hans

Ulrich Boas, 119-149. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Boas, Hans Christian. 2008. Toward a frame-constructional approach to verb classification. In Eulalia Sosa Acevedo and Francisco José Cortés Rodríguez, eds., Grammar, Constructions, and Interfaces: Special issue of Revista Canaria de Estudios Ingleses 57: 17-48.

Boas, Hans Christian. 2009. Multilingual FrameNets in Computational Lexicography: Methods and Applications. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Bodomo, Adams B. 2006. The structure of ideophones in African and Asian languages: The case of Dagaare and Cantonese. In John Mugane et al., eds., Selected Proceedings of the 35th Annual Conference on African Linguistics: African Languages and Linguistics in Broad Perspectives, 203-213. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Bradshaw, Joel. 2006. Grammatically marked ideophones in Numbami and Jabêm. Oceanic Linguistics 45, 1: 53-63.

Childs, G. Tucker. 1994. African Ideophones. In Leanne Hinton, Johanna Nichols, and John J. Ohala, eds., Sound Symbolism, 178-204. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Church, Kenneth, William Gale, Patrick Hanks, and Donald Hindle. 1991. Using statistics in lexical analysis. In Uri Zernik, ed., Lexical Acquisition: Exploring On-Line Resources to Build a Lexicon, 115-164. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum. Cole, Desmond T. 1955. An Introduction to Tswana Grammar. London: Longmans,

Green and Co.

Croft, William. 2003. Lexical rules vs. constructions: A false dichotomy. In Hubert Cuyckens, Thomas Berg, René Dirven, and Klaus-Uwe Panther, eds., Motivation in Language: Studies in Honour of Günter Radden, 49-68. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Diffloth, Gérard. 1972. Notes on expressive meaning. Papers from the Eighth Regional Meeting, 440-447. Chicago Linguistic Society.

Dingemanse, Mark. 2011. The Meaning and Use of Ideophones in Siwu. Ph.D. dissertation, Radboud University/Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics.

Doke, Clement Martyn. 1935. Bantu Linguistic Terminology. London: Longmans, Green, and Co.

Evans, Nick and Hans-Jürgen Sasse. 2007. Searching for meaning in the Library of Babel: Field semantics and problems of digital archiving. Archives and Social Studies: A Journal of Interdisciplinary Research 1, 0: 63-123.

Fillmore, Charles J. 1982. Frame semantics. In the Linguistic Society of Korea, ed., Linguistics in the Morning Calm, 111-137. Seoul: Hanshin.

Fillmore, Charles J. 1985. Frames and the semantics of understanding. Quaderni di Semantica: Rivista Internazionale di Semantica Teorica e Applicata 6, 2: 222-254. Fillmore, Charles J. and Collin Baker. 2010. A frames approach to semantic analysis. In

Bernd Heine and Heiko Narrog, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Analysis, 313-340. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fillmore, Charles J. and Miriam R. L. Petruck. 2003. FrameNet glossary. International Journal of Lexicography 16, 3: 359-361.

Fortune, George. 1962. Ideophones in Shona: An Inaugural Lecture Given in the University College of Rhodesia and Nyasaland on 28 April 1961. London: Oxford University Press.

Hamano, Shoko. 1998. The Sound-Symbolic System of Japanese. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Hasada, Rie. 2001. Meanings of Japanese sound-symbolic emotion words. In Jean Harkins and Anna Wierzbicka, eds., Emotions in Crosslinguistic Perspective, 217-253. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Hinton, Leanne, Johanna Nichols, and John J. Ohala. 1994. Introduction: Sound-symbolic processes. In Leanne Hinton, Johanna Nichols, and John J. Ohala, eds., Sound Symbolism, 1-12. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hirose, Masayoshi. 1981. Japanese and English Contrastive Lexicology: The Role of Japanese “Mimetic Adverbs.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley.

Imai, Mutsumi, Sotaro Kita, Miho Nagumo, and Hiroyuki Okada. 2008. Sound symbolism facilitates early verb learning. Cognition 109, 1: 54-65.

Itô, Junko, and R. Armin Mester. 1995. Japanese phonology. In John A. Goldsmith, ed., The Handbook of Phonological Theory, 817-838. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

Iwata, Seizi. 2008. Locative Alternation: A Lexical-Constructional Approach. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Johnson, Marion R. 1976. Toward a definition of the ideophone in Bantu. Ohio State University Working Papers in Linguistics 21: 240-253.

Kakehi, Hisao, Ikuhiro Tamori, and Lawrence C. Schourup. 1996. Dictionary of Iconic Expressions in Japanese. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Kita, Sotaro. 1997. Two-dimensional semantic analysis of Japanese mimetics. Linguistics 35, 2: 379-415.

Kita, Sotaro. 2008. World-view of protolanguage speakers as inferred from semantics of sound symbolic words: A case of Japanese mimetics. In Nobuo Masataka, ed., The Origins of Language: Unraveling Evolutionary Forces, 25-38. Tokyo: Springer. Kunene, Daniel P. 1965. The ideophones in Southern Sotho. Journal of African

Linguistics 4: 19-39.

Lakoff, George P. 1987. Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal about the Mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lu, Chiarung. 2006. Giongo/gitaigo-no hiyuteki-kakutyoo-no syosoo: Ninti-gengogaku-to ruikeiron-no kanten-kara [Aspects of figurative extension of mimetics: From cognitive linguistic and typological perspectives]. Ph.D. dissertation, Kyoto University.

Mphande, Lupenga. 1992. Ideophones and African verse. Research in African Literatures 23, 1: 117-129.

Noss, Philip A. 2003. Ideophone. In Philip M. Peek and Kwesi Yankah, eds., African Folklore: An Encyclopedia, 180-181. New York/London: Routledge.

Nuckolls, Janis B. 1996. Sounds like Life: Sound-Symbolic Grammar, Performance, and Cognition in Pastaza Quechua. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ono, Masahiro, ed. 2007. Giongo/gitaigo 4500: Nihongo onomatope ziten [4500 mimetics: A dictionary of Japanese mimetics]. Tokyo: Shogakukan.

Petruck, Miriam R. L. 1996. Frame semantics. In Jef Verschueren, Jan-Ola Östman, Jan Blommaert, and Chris Bulcaen, eds., Handbook of Pragmatics, 1-13. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Ruppenhofer, Josef, Collin F. Baker, and Charles J. Fillmore. 2002. Collocational information in the FrameNet database. In Anna Braasch and Claus Povlsen, eds., Proceedings of the Tenth EURALEX International Congress, Volume I, 359-369. Samarin, William J. 1971. Survey of Bantu ideophones. African Language Studies 12:

130-168.

Schaefer, Ronald P. 2001. Ideophonic adverbs and manner gaps in Emai. In F. K. Erhard Voeltz and Christa Kilian-Hatz, eds., Ideophones, 339-354. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Schourup, Lawrence C. 1993. Nihongo-no kaki-kotoba/hanasi-kotoba-ni okeru onomatope-no bunpu-ni tuite [On the distribution of mimetics in written and spoken Japanese]. In Hisao Kakehi and Ikuhiro Tamori, eds., Onomatopia:

Gion/gitaigo-no rakuen [Onomatopia: A utopia of mimetics], 77-100. Tokyo: Keiso Shobo.

Shibasaki, Reijirou. 2009. Semantic constraints on the diachronic productivity of Japanese reduplication. Grazer Linguistische Studien 71: 79-98. Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz.

Slobin, Dan I. 1997. Mind, code, and text. In Joan Bybee, John Haiman, and Sandra A. Thompson, eds., Essays on Language Function and Language Type: Dedicated to T. Givón, 437-467. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Snell-Hornby, Mary. 1983. Verb-Descriptivity in German and English: A Contrastive Study in Semantic Fields. Heidelberg: Carl Winter Universitätsverlag.

Talmy, Leonard. 2000. Toward a Cognitive Semantics, Volume II: Typology and Process in Concept Structuring. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Tamaoka, Katsuo, Sachiko Kiyama, and Yayoi Miyaoka. 2011. Sinbun-to syoosetu-no koopasu-ni okeru onomatope-to doosi-no kyooki-patan [Collocation patterns of sound-symbolic words and verbs in corpora of a newspaper and novels]. Gengo kenkyu 139: 57-84.

Tamori, Ikuhiro. 1988. Japanese onomatopes and verbless expressions. Journal of Cultural Science 24, 2: 105-129. Kobe University of Commerce.

Toratani, Kiyoko. 2006. On the optionality of to-marking on reduplicated mimetics in Japanese. In Timothy J. Vance and Kimberly Jones, eds., Japanese/Korean Linguistics, Vol. 14, 415-422. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.

Toratani, Kiyoko. 2007. An RRG analysis of manner adverbial mimetics. Language and Linguistics 8, 1: 311-342.

Toratani, Kiyoko. 2010. The role of sound-symbolic forms in motion event descriptions: The case of Japanese. Ms., York University.

Tsujimura, Natsuko and Masanori Deguchi. 2007. Semantic integration of mimetics in