Tenure Choice and User Cost for Housing

♦May, 01

Fukuju YAMAZAKI Department of Economics

Sophia University,

7-1 Kioi-Cho Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo. Japan 102-8554

Yoshihisa ASADA Department of Real Estate

Meikai University,

8 Akemi, Urayasu-city, Chiba. Japan 279-8550

♦ We would like to thank Kikuo Iwata, Yoshitsugu Kanemoto, Tatsuo Hatta, Takako Idee and Takahisa Dejima for their very helpful comments.

Tenure Choice and User Cost for Housing

Fukuju YAMAZAKI Department of Economics

Sophia University,

7-1 Kioi-Cho Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo. Japan 102-8554

f-yamaza@sophia.ac.jp Phone/Fax +81 3 3238 3208

Tenure Choice and User Cost for Housing

Abstract

We present a model that determines both the discrete tenure choice and continuous demand for floorspace simultaneously, introducing agency costs into rental market and transaction costs into owner occupation, respectively. First, we show that while consumers of higher income prefer larger housing in owner occupied market, consumers of lower income choose smaller housing in rental market. Second, we examine how the user cost of housing capital, the transaction cost and the agency cost respectively affect the lot size of housing and the rate of owner occupation. Third, we empirically examine whether our model can explain the tenure choice, using the data of housing market in Tokyo.

JEL Classification Number D23.K12.R21

1. Introduction

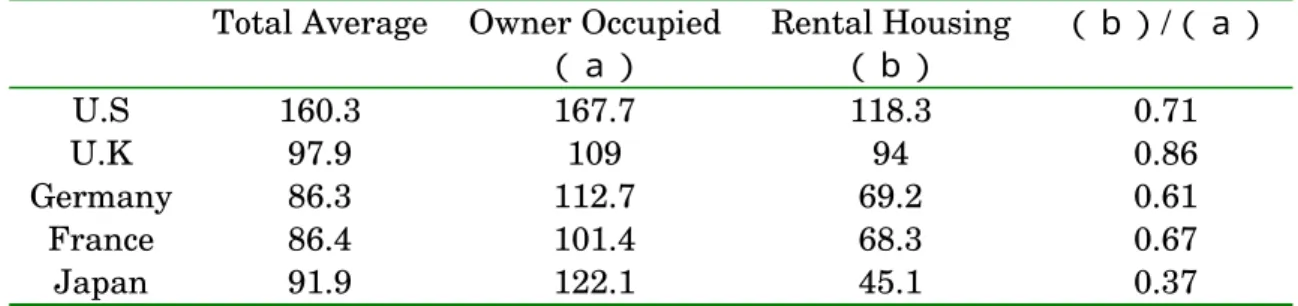

What are the determinants of tenure choice and housing size? If there is no imperfections and taxes, we can not derive the inner solution determining the ratio of renters to owner occupants as market equilibrium. Regardless of whether households own or rent, they can achieve the same set of consumption possibilities through the market transaction. Nevertheless, there is a remarkable difference between the size of owner occupied housing and rental housing in many countries, as shown by Table 1 below.

We have to treat both the discrete and continuous aspects of housing decisions simultaneously. The former is discrete choice of tenure and the latter is continuous demand for floorspace given the tenure. As King [1980] shows, when we explain these phenomena simultaneously, we have to impose strong theoretical restrictions on both the functional form and parameters that enter into the equations determining the discrete and continuous decisions. The owner occupancy means self production of housing services within the households. As Coase [1939] points out, transaction costs plays a crucial role in determining to what extent the organization integrates the market transaction (Williamson and Sydney[1991]). Similar to the firms, households face the same problem whether they own a house to produce residential service for themselves or rent it from others. Then we have to introduce both transaction cost of using the market and agency costs of rental market into the model determining owner occupants or renters. 1

Weiss [1978] introduces the production function of housing services that are different across the consumers, and explains the tenure choice between owning and renting. While a consumer with more efficient technology prefers owner occupied to renting, a consumer with less efficiency prefers renting to occupation. Henderson and Ioannides [1983] present a model showing how housing investment and housing consumption are determined. By introducing agency cost into rental market, they attempt to examine what the determinants of tenure choice are in the housing market. Miceli[1989] examines tenure choice considering a trade off between adverse selection in renting and transaction cost of owning. 2

1 Arnott[1987] suggests the importance of transaction cost and tenure security.

2Although Miceli’s model hasthe similar setting to our model, the model can not directly tested by any empirical data. We

They can not, however, derive the simple relationship between the tenure choice and income. Although many empirical studies have followed the seminal and theoretic studies of Weiss [1978], Henderson and Ioannides [1983], and Miceli [1989], they do not pay attention to the cost of using market transaction.

The first aim of this paper is to present a model that determines both the discrete tenure choice and continuous housing demand given the tenure simultaneously. We derive a close relationship among the tenure choice, income, housing demand and transaction cost. We show that although consumers of higher income prefer larger housings in owner occupied market, consumers of lower income choose smaller housings in rental market under perfect capital market and no tax.

We focus on the fixed and variable cost of capital. Owner occupation needs the fixed cost of transaction cost, whereas rental housing requires variable agency cost. While the fixed cost mainly determines the size of owner occupied housing, the agency cost in rental market is shown to affect the lot size of rental housing. Smaller housings are provided in rental market at cheaper rent, because owner occupied housing with smaller lot size costs relatively high transaction cost. Meanwhile, larger housings are supplied in owner occupied market, because the cost is lower than that of the rental market by the agency cost.

Second, we examine how the user cost of housing capital, the transaction cost and the agency cost respectively affect the lot size of housing and the rate of owner occupation. As usual, a rise in real interest rate raises the user cost that decreases both of the lot size of housing in rental market and owner occupants. A rise in marginal user cost decreases the rate of owner occupation in housing market, because owner occupants with larger houses incur more by a rise in user cost, rather than the renters with smaller house. The transaction cost in purchasing houses decreases the floorspace of the owner occupied housings and the rate of owner occupations, although it dose not effect the size of rental housings.

Thirdly, we explore empirically using the data of Tokyo whether the user cost of housing capital varies depending on the floor size. We find that the user cost of housing capital consists of both fixed and variable part. The owner occupation is shown to have larger fixed

present a model that can be verified empirically.

cost and smaller average variable cost than rental housing. This means the sufficient condition for that the smaller housing is provided by the rental market, though the larger housing is owner occupied.

The organization of this paper is as follows. Section 2 presents the observation on the floorspace in each country. In order to explain this phenomenon, we present a model in section 3 introducing agency costs in rental market and transaction costs in owner occupation. In section 4, we investigate empirically whether our model can explain tenure choice of housing market in Japan.

2. Lot sizes of housing in Each Country

First, we compare the sizes of housing services among countries. Table 1 shows the sizes of owner occupied and rental housing for each country. Both housing floorspace of the U.S. are remarkably larger than those in other countries. In regard of only owner occupied, the housing sizes are almost the same among countries except for the U.S.. It is interesting that the relative size of rental housing to owner occupied house shows similar values, 0.61-0.86 except Japan. The value of Japan is significantly lower than other countries. Table 1 shows an important feature about housing size, which is owner occupied housings are generally larger than the rental housing in each countries.

We study how the rental housing becomes smaller than the owner occupied housing does. Then we pay attention to both of the transaction cost in house purchasing and the agency cost in rental housing. An asymmetric information between renters and owners may also cause to produce the difference in floorspace.

Table 1. Comparison of Housing Floorspace Per Unit (m2)

Total Average Owner Occupied

(a)

Rental Housing

(b)

(b)/(a)

U.S 160.3 167.7 118.3 0.71

U.K 97.9 109 94 0.86

Germany 86.3 112.7 69.2 0.61

France 86.4 101.4 68.3 0.67

Japan 91.9 122.1 45.1 0.37

Source: The Department of Construction [1996], White Paper of Construction, Japan.

3. A Model of Tenure Choice 3.1 Consumer Behavior and User Cost

First we consider the tenure choice of a representative consumer between rental housing and owner occupied housing. We assume a strictly concave utility function of housing service h, and a consumer good x (numéraire). The representative individual maximizes his utility under the budget constraint of constant income Y and rent R.

Utility function is:

U = u h Y( , − R) (1)

where Y − R = x. The consumer’s indifference curves are depicted in Figure 1. The indifference curve being at south-east means higher utility. The marginal rate of substitution under given income is,

dR dh

u u

u y const h , : x

= >0 (2)

where U u

j = ∂j

∂ (j = h, x). Each indifference curve is drawn under each given income

and upward sloping.

Assuming that marginal rate of substitution is decreasing, we have,

>0

=

x h

u u x dh dR

Y ∂

∂

∂

∂ (3)

The indifference curve I1 I1 implies the curve of consumer with higher income than the curve I0

I0. The slope of tangent to indifference curves with higher-income is steeper than that of lower-income. The marginal willingness to pay rent for a higher income consumer is greater than for a lower income consumer.

Now consider the supply side of housing service under perfect competition. A landlord provides a renter and/or himself with a housing service. In the competitive equilibrium, total cost must be equal to the total revenue. Under the condition that there is a perfect capital market and no tax, the opportunity cost of owning a house consists of interest and depreciation cost. The return is housing rent and the capital gains of housing.

Ι

∗Rent A’ A E w B

R w I 1

C

R r

E’ r

E r I 0

I * I 1

I 0

O h r h 1 h 0 h 2 h w

Housing Service

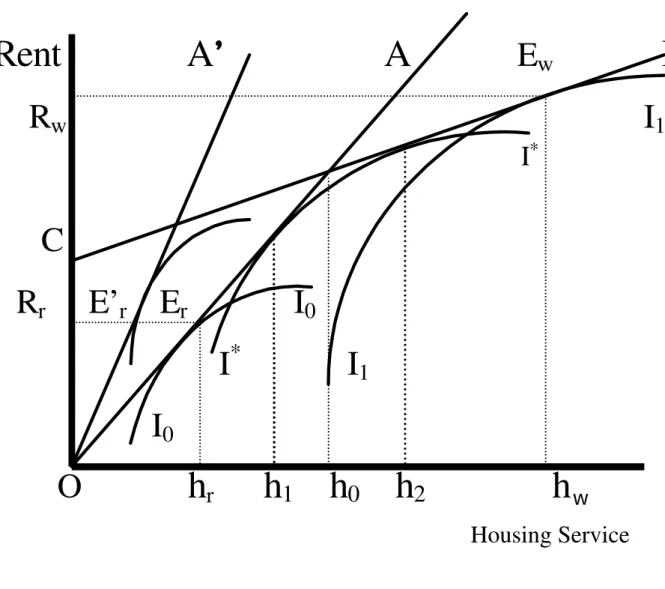

Figure 1 Housing Tenure Choice

Assuming that the unit price of housing is p, we can obtain the equilibrium condition in the rental market;

r

r

i ph

R = ( + δ − π + β )

(4)where Rr is total rent for rental housing, hr is housing size, i is the interest rate, δ and π are the depreciation rate of capital and the rate of inflation, respectively. The landlord requires risk premium β in rental unit. The right hand side of the above equation is the user cost of housing capital under perfect capital market and no tax. At the equilibrium, the rent of rental housing Rr must be equal to the user cost of the housing capital.

A house owner asks for a risk premium β in rental housing, which is not required in owner-occupied housing. As usual, rental contract involves agency cost under asymmetric information. Under the incomplete contract, there are some obstacles preventing from efficient allocation of resources. Moral hazard and adverse selection in the rental market may cause to accrue inefficiencies.

The quality of rental housing can be worsened by failure of renters to take care of house or depreciated by nature. In some cases it is very difficult to identity which causes to worsen the quality, the renter’s failure, or other issues. There are “good” renters and “bad” renters. The owners can not identify “good” renters from “ bad” renters. They can not also monitor the behavior of renters in detail and can not verify the failure of renters in courts. It is because the owner requires the premium in renting houses. We can assume the premium per a unit value constant without any loss of generality.

Similar to the rental unit, the owner equalizes his imputed rent with the user cost. Assuming transaction cost per unit and per period C, we have the following the equilibrium condition for owner occupied housing;

Rw = (i + δ − π)phw + C (5)

where Rw and hw are the imputed rent and the lot size of owner occupied housing, respectively. While the transaction cost in rental contract is negligible, the transaction cost in purchasing and owning house is much too large to neglect. We have to spend much time and various

costs searching for a good house, contracting with homebuilders, registering houses and so on.3 The owners of rental apartments also incur the transaction costs in searching and buying good apartment. However, such transaction costs have the aspects of fixed cost, so that the average transaction cost is decreasing with housing unit. The transaction cost per unit is assumed to be negligible for apartment with a lot of families.4

Equation (4) and (5) are depicted in Figure1. Assuming as usual that i +δ >π , we have the OA line which shows the positive relationship between the market rent and the housing size of rental housing. The line CB with the intercept of fixed cost displays the relationship of owner occupied housing. The slope of OA is steeper than CB, because the rental housing involves the risk premium β, which the owner occupier does not incur.

The supply price in rental market is lower than the supply price of owner-occupied below the certain housing size ho at which the OA line intersects with the CB line. Regarding the housing size over ho, the cost of owner occupied housing service is less than the rental housing.

3.2 Market Equilibrium for Tenure Choice

Let us consider the market equilibrium in both of the rental market and the owner occupied market. In the competitive market, the consumer maximizes the utility under the market line of OA and CB in Figure 1. The consumers of lower income maximize the utility at Er that represents the equilibrium in the market for rental housing. Meanwhile, the consumers of higher income maximize the utility at Ew which is the equilibrium in the market of owner occupied housings. While the consumers of higher income tend to choose owner occupied, the lower income consumers prefer renting to owning.

Let us now consider the consumer with income Y* who is indifferent between renting and owning. The consumer’s indifference curve is shown by I*I* in Figure 1, which is tangent to both of the supply price OA and CB. Since the slope of indifferent curve increases with the income, consumer with higher income than Y* prefers owner occupation with larger housing

3Kanemoto [1990] says that the cost of purchase contract is more expensive than the rental contract. Similarly, Arnott [1987] points out that “Owners face greater transaction cost associated with moving than renters.”

4This is not a crucial assumption. Our conclusions do not change, if the transaction cost of owner occupied housing is higher than that of rental housing. See the discussion in section 4.

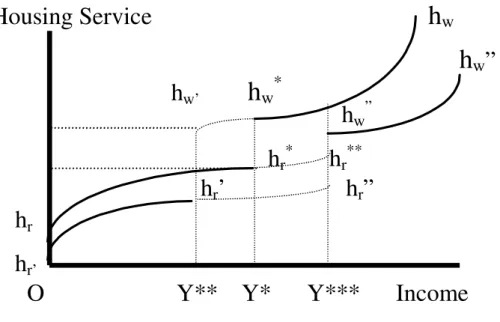

than h2. Similarly, consumer with lower income than Y* chooses smaller rental housing than h1. Under the condition of supply price OA and CB, the market does not provide the housing with size between h1 and h2. Thus housing size jumps from h1 to h2 at income Y* in Figure 2.

The relationships between tenure choice, housing size and income are depicted as hrhr

*hw

*hw

curve in Figure 2. hrhr*and hw*hw are the relationships for rental housing and owner occupied, respectively. If the housing services are not inferior goods, consumers with higher income choose larger housing services. Consumers of lower income than Y* prefer renting to owning. At the point Y*, consumers change tenure choice from rental housing to owner occupied discretely. It is indifferent for consumers with certain income Y* to choose between renting and owning. At higher income than Y*, consumers prefer owning to renting. The housing size thus jumps at Y* in Figure 2.

Housing Service h

wh

w”

h

w’h

w*

h

w”h

r*h

r**h

rh

r’ h

r”

h

r’O Y** Y* Y*** Income

Figure 2 Income and housing Service

Consumer of higher (lower) income than Y* prefer owning (renting) to renting (owning) given the market line of equation (4) and (5). At certain critical income the following condition holds;

(6) The hrhr*hw*hw curve in Figure 2 gives the theoretical explanation to the phenomenon shown in section 2. Table 1 shows that the rental housing size is smaller than the owner occupied in each country does. Figure 2 shows the results of the tenure choice of the equilibrium. While consumers with lower income prefer smaller housings in rental market to owning, consumers with higher income prefer larger housings of owner occupied to renting. Smaller housings are provided in rental market, because rental market can provide smaller houses at cheaper rent, shown by the OA line below ho in Figure 1. Conversely, larger housings over ho are supplied in owner occupied market, because the cost of owner occupied houses is lower than the cost of rental market.

3.3 Comparative Statics

Now examine the effect of risk premium on the housing size. A rise in risk premiumβ increases the unit rent of rental housing to shift the market line up from OA to OA’ in Figure 1. It increases market rent of rental housings. Thus smaller housings are achieved in the new equilibrium E’r in rental housing. Such risk premium brings about the rise in the ratio of owner occupier towards renter. The critical income level Y* determines whether renting or owning is decreased by the risk premium. A decrease in Y* means greater ratio of owner occupant in housing market under given the income distribution. The effects on the housing floorspace by risk premium is depicted as curve hrhr

*hw

*hw which jumps at a lower income Y** than Y* in Figure 2.

Many countries that have experienced severe scarcity of rental housing during and after the war have tenure security law. There is another uncertainty due to the tenant law that increases risk premium in rental housing. Tenant security law in Japan gives a greater favor to renters compared to other countries. Especially the courts compare the owners’ economic condition with the condition that the renters would face if they were evicted. The court judges if the eviction can be justified from the income distribution point of view. The owners must show a

) ) (

, ( ) ) (

,

(hr Y* i hr u hw Y* C i hw

u

U = − +δ −π +β = − − +δ −π

“rightful cause” in order to evict the renters from the residence. There is uncertainty in the verifiability of the rightful cause. Accordingly, the tenant security law increases agency cost in rental housings of Japan.5 Thus the law decreases seriously the size of rental housing in Japan.6

Next consider whether a change in transaction cost of owner occupied housing affects the housing demand and the owner occupation rate. An increase in transaction cost associated with purchase contract causes an upward shift of the CB line in Figure 1 to accrue higher rent. Owner occupiers decrease housing demand and floorspace, because of the higher imputed rent. A higher rent increases a critical income level that determines discrete choice of tenure. Thus transaction cost causes smaller floorspace for owner occupied housings and lower rate of owner occupation relative to renting. The effect of transaction cost is depicted by hrhr

**hw

”hw

”.

A rise in interest rate increases the marginal rent of both housings. It makes both the OA line and the OB lines steeper. An increase in marginal rent decreases the floorspaces of both rental housing and owner occupied housing, unless the housing services are inferior goods. Thus the hrhr*hw*hw curve shifts down in Figure 2, due to the rise in marginal rent. The rate of owner occupation depends on the critical income level determining the tenure choice. Differentiating equation (6) gives the following result;

dY di

u h u h u u

x w

w x

r r x w

x r

*

= −

− >0 (7)

because hw > hr and uxw >urx. uxw and uxr is the first derivative of utility function by consumption goods when consumers choose owner occupied (w) or rental housing (r), respectively. The critical income increases due to higher interest rate. A decrease in inflation rate and the rise in depreciation rate have the same influence as the rise in interest rate. Thus a higher user cost of housing capital decreases the rate of owner occupations, because the

5Note that the size of rental housing in Japan is remarkably small as shown in Table 1.

6Yamazaki [1996] and Yamazaki and Idee [1996] examine whether the capital gains tax has the lock-in effect, assuming that there are no rental market for land. Because of the tenant security law, the rental market for lands does not work well in Japan.

critical income increases with the user cost. Then the feature of tenure choice in Figure 2 is depicted as the hr

’ hr

”hw

”hw

”.

It is not surprising to derive such conclusions. Examine who incurs larger cost between owner occupiers and renters, when the user cost increases due to higher interest rate. The increase in cost of owner occupation is more than that in cost of rental housing, because the housing space of owner occupancies is larger than the rental housings. A higher interest rate costs more to own than rent. Thus, a rise in user cost decreases the rate of owner occupations. The rate of owner occupation and the average floorspace depend on the shapes of the market lines and income distribution. A greater variance of the income distribution generally produces greater difference of floorspace between renting and owning, because lower income consumers prefer smaller lot size of rental housings and higher income consumers choose larger floorspace of owner occupied housings.

4. An Empirical Study 4.1 Data

The tenure choice model developed in the previous section shows that the supply price of rental housing is lower at the smaller size of housing and higher at the larger housing size than the supply price of owner occupied housing. In this section, we examine empirically whether it is true using the Japanese housing data. Specifically, we explore whether estimated equation of (4) has smaller constant and larger coefficient of housing value than those of the estimated equation of (5). If it is the case, the estimated supply price curve of OA intersects with the estimated curve CB in Figure 1 as well as our model predicts.

While estimation of equation (4) and (5) requires the data about rent and stock price of housing capital, the data about the imputed rent for owner occupied housings are obviously not available and those about the stock price of rental apartments are also not available in Japan. At first, we estimate the hedonic price functions about rent and stock price respectively, and extrapolate the imputed rent of owner occupied and the stock price for apartments by using the estimated hedonic functions. Because both the unit rent and the stock price of housing depend on locations, structure, accessibility to CBD of Tokyo and so forth, we introduce several

variables to estimate the hedonic functions. If the hedonic functions are statistically significant, it can be justified to extrapolate the data about imputed rent and stock price.

4.2 Estimations of hedonic functions

To begin with, we estimate a hedonic function of a stock price (per square meter) for ready-built condominiums7. We collected cross-section data on several hedonic variables (X) that may be expected to affect housing market along the JR (Japan Railway) line (Shinjuku-Tachikawa), Keio-Inogashira line, Keio line (Shinjuku-Hachioji), Odakyu line (Shinjuku-Sobudaimae), and Tokyu line. 8

In Column (A) of table 2, we present the result of hedonic estimation. We employ the hedonic variables such as a time distance from the nearest railroad station to the CBD, and the time from the station to the house. The age of house and the story at which house locates are also used as the quality of housing services. Similarly we employ representing a certain area dummy representing location environment (Tokyu Dummy, Kanagawa, Tokyo ward, Seijo, Kichijoji, Yoyogiuehara Dummy).

The estimation shows satisfactory results and all the estimated parameters conform to urban economic theory predictions. We find that the better accessibility to the CBD increases the stock price of housing, and the age of house depreciates the stock price. The housing price on higher story relative to the total stories is higher than the lower story because of better view. The estimated equation seems to have a good performance in explaining stock price behavior and all of the variables are significant.

Our second task is to estimate a rent function under the assumption that location, structural variables affect rent R. We employ the same hedonic variables as in a stock price function. Here, note that we also use the data of unit rent through dividing total rent by housing size. Similar to the stock price function, the estimated rent function reveals good performance in explaining rent behavior as shown by Column (B) of Table 2. A shorter commuting time significantly raises the rent and the aged apartment has lower rents. A house on higher story

7Recruit [1997a] provides us with the data of hedonic variables that is relevant to our estimation.

8 Hatta and Ohkawara [1994] describe the population and employment structures of the metropolitan area of Tokyo in detail.

relative to the apartment’s total number of stories increases the rent, because higher story may have finer view. The good performance can successfully justify using the estimated function to extrapolate imputed rent for owner housing and the stock price for rental condominiums.

Table2. Estimated hedonic functions for rents and stock price

Stock price (A) Rent (B) Rent limited to company (C)

Estimated Coefficient

t-value Estimated Coefficient

t-value Estimated Coefficient

t-value

Time Distance to the CBD -0.54596 14.24226 -36.8609 22.87801 -30.5492 5.528219 To the Nearest Sta. -0.39104 7.353587 -41.0619 17.89338 -50.9183 6.306611 Age of housings -1.30091 38.81882 -29.4621 18.00786 -18.7706 3.717706 The floor / Total stories 1.608461 1.688456 133.962 3.596587 108.5676 0.828317 Tokyu Dummy 3.090739 4.522304 285.0608 11.59863 124.5158 1.268439 Kanagawa Dummy -6.4594 8.309817 -225.402 6.107828 -130.147 1.195991 Tokyo Ward Dummy 3.85009 4.342626 199.0591 5.365636 259.2101 1.889628 Seijyo Dummy 7.77337 5.924798 335.6358 7.980958 503.7827 2.837559 Kichijoji Dummy 11.96171 4.375503 805.0039 11.47408 131.1426 0.810776 Yoyogiuehara Dummy 6.310161 2.525284 559.8794 9.338384 949.9654 3.259368 Constant Coefficient 87.30726 61.4306 4384.997 74.66741 3789.763 17.06785

R2 0.737617 0.538720 0.799906

# of Observations 3469 938 66

4.3 Estimation of User Cost

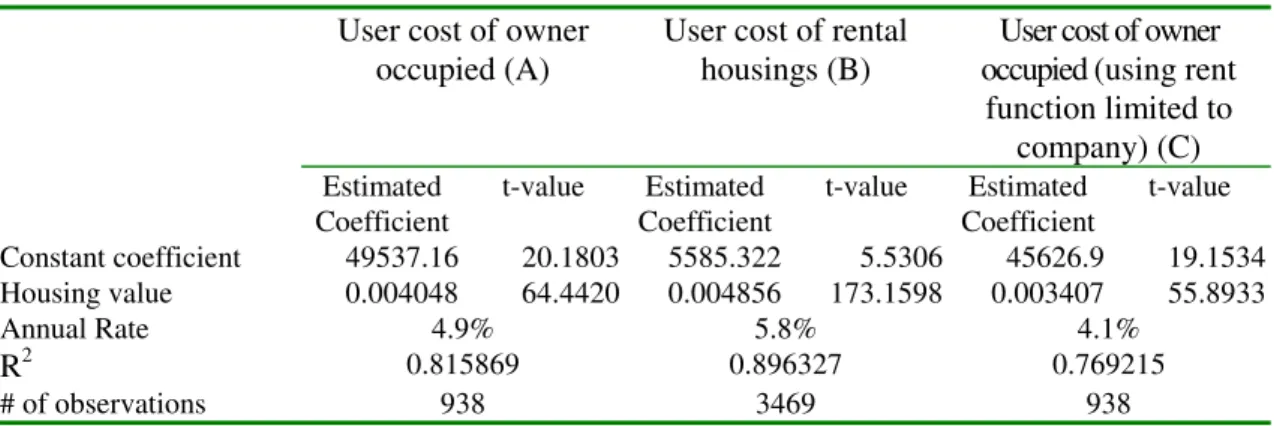

We are now in a position to estimate user cost of rental housings and owner occupied housings respectively. The data about the housing value of owner occupants’ ph are available. Using the data of imputed rent extrapolated by the estimated hedonic function, we run the OLS regression of imputed rent on housing value. The Column (A) of Table 3 shows the estimation results of owner occupied housing. Using the data of condominium price extrapolated by the hedonic function of housing price, we regress the market rent on the stock price of rental apartment by the OLS method. The result of rental housing is also shown in the Column (B) of Table 3.

Comparing these results, we find that owner occupied housing has a larger estimate of intercept and smaller coefficient on housing value than those of rental housing. It should be noted that since we use rent per month as the data of rent, the estimated coefficient on housing value means the marginal user cost by month.9 While the annual rate of user cost is 5.8% for

9 The contract period of rental apartment are usually 24 months in Japan. The tenant needs to pay the deposit and the key money at the beginning in addition to monthly rent. In calculating the data on actual rent per month, we divide the key money

rental housing, that for owner occupied is 4.9%. The estimated fixed cost is ¥5,585 per month for rental housing, though the fixed cost of owner occupation amounts to ¥49,537 per month. These results satisfies condition for that the supply curve of rental housing intersects with the curve for owner occupied housing at the certain housing size, as depicted by Figure1. In other words, our estimation results are consistent with the model’s prediction that the cost of rental housing is lower (larger) than that of owner occupied housing for smaller (larger) housing. We seem to could obtain quite satisfactory results though this is, of course, problematic method to estimate imputed rent. The data on imputed rent is not available, so that we use the proxy data extrapolated by the estimated hedonic function of rent. Because the structure of rental market may remarkably be different from that of owner occupied, extrapolation using rental housing data may give insufficient prediction of owner occupied. Now consider how to improve our estimation by using more adequate data for substitutable imputed rent. There are the apartments rented for only firms not for individuals in Japan. The firm provides the employees with the rented house as welfare facilities. The quality of such apartment are comparable to that of owner occupied housing in regard to the lot size, location, environment and equipment. Therefore, the data on rent of the apartment might be more substitutable for imputed rent of owner occupied. Using the data we also estimate another hedonic equation of imputed rent. The Column (c) of Table 2 also gives the estimation results, which shows good performance as well as other estimations in Table 2.

Using the rent data by this hedonic function, we estimate regression equation of imputed rent on market housing value of owner occupied housing. The results of estimated equation is shown by the Column (c) of Table 3, comparing the result with that of rental housing, we can also find that the estimates of intercept is larger and coefficient of housing value is lower than those of rental housing. In other words, while the fixed cost of owner occupation is larger than that of rental housing, marginal user cost of owner occupation is lower than that of rental housing. From those results, we can conclude that the user cost of owner occupied is higher than that of rental housing with regard to the housing size below the certain level. This is why consumers with lower income prefer renting to owning. Similarly, we can obtain the conclusion that the user cost of owner occupied is lower than that of renting with the housing

size over the certain level, so that consumer with higher income chooses owning rather than renting.

Table 3. Estimated user cost of rental housings and owner occupied User cost of owner

occupied (A)

User cost of rental housings (B)

User cost of owner occupied (using rent

function limited to company) (C) Estimated

Coefficient

t-value Estimated Coefficient

t-value Estimated Coefficient

t-value

Constant coefficient 49537.16 20.1803 5585.322 5.5306 45626.9 19.1534 Housing value 0.004048 64.4420 0.004856 173.1598 0.003407 55.8933

Annual Rate 4.9% 5.8% 4.1%

R2 0.815869 0.896327 0.769215

# of observations 938 3469 938

The Chow test rejects at 1% significance level the null hypothesis that the estimation of rental housing has the same structural parameters as owner occupied housings, because the F statistics F(2,4403) is 63.187. The same test also rejects the null hypothesis that the rental housing has same estimates as the owner occupied (using hedonic function about rent limited to company) of 1% significance level, because of F(2,4403)=89.372.

5. Concluding Remarks

There is a remarkable difference in floorspace between rental housings and owner occupied housing in developed countries. First, we have presented a model that simultaneously explains the tenure choice and the housing demand. Introducing agency cost and transaction cost, we have examined what produces the difference in the lot size of housing. While consumers with lower income prefer smaller housings in rental market to owning, consumers with higher income prefer larger housings of owner occupied to renting. Smaller housings are provided in rental market at cheaper rent, because smaller owner occupied housing costs relatively high transaction cost. Meanwhile, larger housings are supplied in owner occupied market, because the cost is lower than that of the rental market by the agency cost.

Second, we have examined how the user cost of housing capital, the transaction cost and the agency cost respectively affect the lot size of housing and the rate of owner occupation. As usual, a rise in interest rate raises the user cost that decreases both of the lot size of housing in rental market and owner occupants, as well as a decline of inflation rate. Furthermore, a rise in marginal user cost decreases the rate of owner occupation in housing market, because owner occupants with larger houses incur more by a rise in user cost, rather than the renters with

smaller house. The transaction cost in purchasing houses decreases the floorspace of the owner occupied housings and the rate of owner occupations, although it dose not effect the size of rental housings.

The rate of owner occupation and the average floorspace depend on the shapes of the market lines and income distribution. A greater variance of the distribution produces greater difference of floorspace between renting and owning, because lower income consumers prefer smaller lot size of rental housings and higher income consumers choose larger floorspace of owner occupied housings.

Third, we examine empirically whether our model developed in previous section is true using the data of Tokyo. Estimating the supply price of rental housing and owner occupation respectively, we find that the supply price of rental housing is lower than that of owner occupation below the certain housing size. The supply price of rental housing is higher than that of owner occupied over the certain housing size. This means the sufficient condition for that the smaller housing is provided by the rental market, though the larger housing is owner occupied. We can conclude that our finding conforms with our model.

References

Arnott, Richard., 1987, “Economic Theory and Housing”, Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics, in; E.S. Mills ed., Ch.24. North-Holland, 959-988.

Brueckner, Jan.K., 1986 “The Down Payment constraint and Housing Tenure Choice”, Regional Science and Urban Economics, 519-525.

Coase, R.H., 1937. “The Nature of the Firm”, 4. Economica. n.s.386-405.

Gillingham, Robert., and Hagemann, Robert., 1983, “Cross-Sectional Estimation of a Simultaneous Model of Tenure Choice and Housing Services Demand”, Journal of Urban Economics 14, 16-39.

DiPasquale Denise and Wheaton Willinam C., 1992 “The Cost of Capital, Tax Reform, and the Future of the Rental Housing Market”, Journal of Urban Economics 31, 337-359.

Goodman, Allen.C., and Kawai, Masahiro., 1985, “Length-of-Residence Discounts and Rental Housing Demand: Theory and Evidence”, Land Economics, Vol.61, No.2., 93-105.

Gordon, Roger.H., Hines, James.R. Jr., and Summers, Lawrence.H., 1987, “Notes on the Tax Treatment of Structures”, in The Effects of Taxation on Capital Accumulation (Feldetein ed.), Chicago, 223-256.

Hatta Tatsuo and Toru Ohkawara 1994, “Housing and the Journey to work in the Tokyo Metropolitan Area, in: Y.Noguchi and M. Poerba, eds., Housing Markets in the United States and Japan (University of Chicago Press). pp.87-131.

Henderson.J.V., and Ioannides, Y.M., 1989, “Dynamic Aspects of Consumer Decisions in Housing Markets”, Journal of Urban Economics 26, 212-230.

Henderson.J.V., and Ioannides, Y.M., 1983, “A Model of Housing Tenure Choice”, American Economic Review Vol.73, No.1. .98-113.

Horioka,Charles, Yuji., 1988, “Tenure Choice and Housing Demand in Japan”, Journal of Urban Economics 24, 289-309.

Ionannides, Yannis.M., 1987, “Residential Mobility and Housing Tenure Choice”, Regional

Science and Urban Economics 17, 265-287.

Kanemoto, Yoshitsugu., 1990, “Contract Types in The Property Market”, Regional Science and Urban Economics 20, 5-22.

King, Mervyn.A., 1980, “An Econometric Model of Tenure Choice and Demand for Housing as a Joint Decision”, Journal of Public Economics 14, 137-159.

Li, Mingche.M., 1977, “A Logit Model of Homeownership”, Econometrica, Vol.45, No.5., 1081-1097.

Mayo, Stephan.K., 1981, “Theory and Estimation in the Economics of Housing Demand”, Journal of Urban Economics 10., 95-116.

Miceli, Thomas J., 1989, “Housing Rental Contracts and Adverse Selection with an Application to the Rent-Own Decision”, Journal of the American Real Estate and Urban Economics Association Vol.17, No.4, 403-421.

Order, Robert, Van., 1991, “Housing Demand and Real Interest Rates”, Journal of Urban Economics 29, 191-201

Rosen, Harvey.S.,1979 “Housing Decisions and The U.S. Income Tax”, Journal of Public Economics 11, 1-23.

Weiss,Yoram., 1978, “Capital gains, Discriminatory Taxes, and the Choice between Renting and Owning a House”, Journal of Public Economics 10, 45-55.

Williamson, Oliver.E., and Winter, Sidney.G., 1991, The Nature of the Firm. Oxford University Press.

Yamazaki Fukuju 1996, The Lock-In Effect of Capital Gains Taxation on Land Use., Journal of Urban Economics 39. 216-228

Yamazaki Fukuju and Idee Takako 1997, An Estimation of the Lock-In Effect of Capital Gains Taxation., Journal of the Japanese and International Economics11, 82-104.

Yamazaki Fukuju 1999, The Effects of Bequest Tax on Land Price and Land Use., Japanese Economic Review, forthcoming.