Extensive Reading:

What it is and how we do it

John TENNANT (Received October 11, 2017)

This report describes an Extensive Reading (ER) program at a Japanese university. A brief outline of ER theory and practice in general is given and is followed by a description how the program is implemented at the university. The participation rates of the students and their attitudes towards ER is summarized.

Keyword:extensive reading, ER, ELT

本稿では,ある日本の大学での多読プログラムについて報告する。一般 的な多読の理論と実践方法についての概要をまとめ,次にその大学でプロ グラムがどのように実施されたかについて述べる。学生の参加度と多読へ の姿勢についても簡単に触れる。

キーワード:多読,英語教育

1.Introduction

For a number of years, starting from 2013 and continuing through to 2016, the English teachers in the Center for General Education received funding from the Special Education Fund in order to purchase English reading materials for students at the university. The reading materials were used to implement an extensive reading (ER) program for 1st and 2nd year students who were enrolled in the general English courses (英語Ⅰ−Ⅳ).

This paper will describe the extensive reading program at our university. Initially, what ER is will be outlined and some of the educational thought that provides the theoretical rationale for ER will be detailed. This will be followed by a description of the details of the program and how it is implemented. The final section will be a short discussion of student attitudes towards ER.

2.What is Extensive Reading ? 2.1 ER ― theory and methodology

• the reading of difficult texts which required the use of a dictionary and translation on the part of the reader, and

• the reading of easier texts quickly and fluently.

However, this changed with the development of graded readers during the early and mid-20th century. Graded readers are books for second language (L2) learners written so that vocabulary, grammar, and other elements of the text are controlled for difficulty. These readers have allowed the development of extensive reading as a pedagogical methodology.

In 1998, Day and Bamford published what has become the authoritative guide to extensive reading methodology for teachers, and in 2002 they articulated The Ten Principles of Extensive Reading which succinctly describe ER. Nation and Waring (2013: 6) state that the three most essential of these principles are the following:

1 .Learners read material that is easy to understand. 2 .Learners read as much as possible.

3 .Learners choose what they want to read.

The first two of these principles are theoretically underpinned by Krashen’s input hypothesis (1982: 20︲22) which proposes that learners acquire new language competence by being exposed to comprehensible input with some element (for example, a grammatical structure or vocabulary item) that is just beyond their current competence. This hypothesis is often expressed as i+ where i is considered the learner’s current level of competence and the+ symbolizes the new element being learned. If a learner is exposed to enough comprehensible input then i+ is automatically provided by the input. Since the reading material used for ER is easily understood, learners can focus on the message of the text without expending a great deal of effort on how the meaning is expressed. In this way, a new language element can be acquired because it occurs in multiple, meaningful contexts since the learners read as much as possible. In other words, ER can provide in L2 an immersive learning experience similar to that of learning L1.

The third principle, learners choose what they want to read, is underpinned by the affective filter hypothesis and the idea of learner autonomy. Learner autonomy is the freedom for a learner to control his or her learning. By allowing the learner choice in what to read, ER encourages learner autonomy. The learner is free to choose what to read and what not to read. If a book is not interesting or too difficult to understand, the learner may stop reading it anytime. Which brings us to the affective filter hypothesis. This hypothesis claims that affective variables (such as motivation, self-confidence, or anxiety)“act to impede or facilitate the delivery of input” to the learner (Krashen, 1982: 32). By allowing the learner choice, the affective filter can be lowered. Interesting reading material is more motivating. Being able to comprehend an easy text may increase self-confidence and reduce anxiety.

2.2 Implementing an ER program

There are a number of issues that must be considered when setting up and running an extensive reading program. Among these are:

• building and maintaining a collection of reading materials, • ensuring that students actually read, and

• monitoring and assessing the reading done by students.

The most common impediment for starting an ER program is the need for reading materials. Graded readers are the most common type of materials, but leveled readers are also used in many ER programs. Leveled readers are short books intended to help children, who usually speak English as their L1, learn to read English. So like graded readers, they feature language that is simplified compared to normal children’s storybooks. Through the use of graded readers and leveled readers, an ER program can provide easy to understand reading materials.

However, since learners choose what they want to read a wide variety of books is necessary in order to provide enough material that is both interesting and at varying levels of difficulty. Ideally, there should be many more books available than readers. One conservative estimate is that there should be at least 3 books available per each learner in the program (Extensive Reading Foundation, 2011: 5). For example, a program with 200 learners should have a collection of over 600 books. As well, some books will be more popular than others, so there will be a need for multiple copies of the more popular titles.

Having enough reading materials is a necessary prerequisite for a successful ER program, but it is often not sufficient. The learners must also read, so the teacher must provide time for reading in addition to the books. One of Day and Bamford’s principles is that reading is silent and individual (2002), and Nation and Waring suggest that “one-quarter of total course time . . . should be spent on extensive reading or listening”(2013: 19), so it is recommended that learners are given time in class to do sustained silent reading (SSR). This time could be as short as five or ten minutes or much longer. In most ER programs, the SSR time is supplemented with out-of- class reading done as homework. During SSR, a teacher can monitor students to ensure that they are reading; however, something more is needed to monitor any reading homework.

Book reports are one kind of activity that have been used for monitoring, but they are usually discouraged in ER programs. Book reports take time, time that can be better spent reading other books. As Day and Bamford state, “reading . . . is at the center of the extensive reading experience, just as it is in reading in everyday life”(2002). Learners cannot read as much as possible if they are writing reports. Book logs are a compromise, in that students are not expected to write in-depth reports about their reading, but they are expected to write down a brief amount of information for every book they read. Book logs usually include the title of the book, the date when the book was finished, and a brief impression or description of the book (often written in the student’s L1). Other information included might be the length or

Until recently, book logs were perhaps the most common form of monitoring; however, on-line book quizzes have become increasingly prevalent. The book quiz systems provide an environment where students can take a short quiz after they have read a book. When the student passes the quiz, the system automatically makes a database entry creating a log for the student which records information such as the book title, the date finished, the book’s length, and its level of difficulty. The quiz systems allow the teacher to monitor the reading of many learners by treating each passed quiz as a proxy for a book read. Teachers can easily assign grades since the system can provide a summary report of the quizzes passed by the learners. Examples of such quiz systems include the Moodle Reader module, M-Reader, and Xreading.

2.3 Evidence for ER

What evidence is there that extensive reading is effective for learning English? There have been a number of quantitative studies done which show the effectiveness of ER. Day and Bamford (1998: 33︲34) cite an influential study by Elley and Mangubhai (1981) which describes the effect of a “book flood” on elementary school students in Fiji. Elley and Mangubhai found that the students made gains in both reading and general proficiency when compared eight months later with a control group who had not had equivalent access to books.

More recently and in the Japanese context, there have been a number of studies (Furukawa, 2008; Beglar and Hunt, 2014; Nishizawa and Yoshioka, 2016) that have investigated quantitatively the relationship between the amount and the difficulty of the materials read and gains made in reading proficiency. For these studies, the volume read is measured in words, and difficulty of reading materials is usually measured in headwords. The number of headwords refers to a list of permissible vocabulary used to write the text. So a 300 headword book is limited to very high frequency vocabulary, in other words the most commonly used English words, while a 600 headword book will include less common yet still high frequency vocabulary. However, these headword lists are are dependent on publishers, so a 10-point readability scale has been developed in Japan. This scale is known as yomiyasui level (YL), in which a YL of 0.0 is used for an illustrated book with no text and a YL of 10.0 indicates the book is a difficult read for native speakers of English. Leveled readers for L1 children and graded readers for L2 learners of English usually range between 0.1 to 6.0 on the YL scale.

English study.

In a second study done at a Japanese university, Beglar and Hunt investigated the reading rate gains made by 76 students over one school year (2014). Reading rate is measured as the number of words read per minute while maintaining a high level of comprehension. Beglar and Hunt found that the students who read the most, generally over 200,000 words, had the greatest improvement. More importantly, they found that reading easy simplified texts was most effective. The students who focused on reading texts with headword counts of 1600 or less (YL <4.0) had average reading rate gains of approximately 33 wpm (from 97 to 130 wpm). The students who tended to read the most difficult simplified texts (4.0<YL<6.0) had the worst outcomes and actually suffered a small decline in reading rates.

In a longitudinal study of engineering students at a technical college in Aichi, fourteen students read at least 1,000,000 words over seven year period (Nishizawa and Yoshioka, 2016). Over the seven years, the students took the TOEIC test at least once each year. The average of the students’ TOEIC scores improved from 355 to 562 points, an average improvement of about 200 points. This study suggests that reading 150,000 to 200,000 words per year is a reading target that is both feasible and likely to lead to reading proficiency gains. The authors found a significant correlation between reading a lot of very easy materials (YL<1.1) initially and reading proficiency gains.

3.Extensive Reading at HKGU 3.1 An outline of the HKGU program.

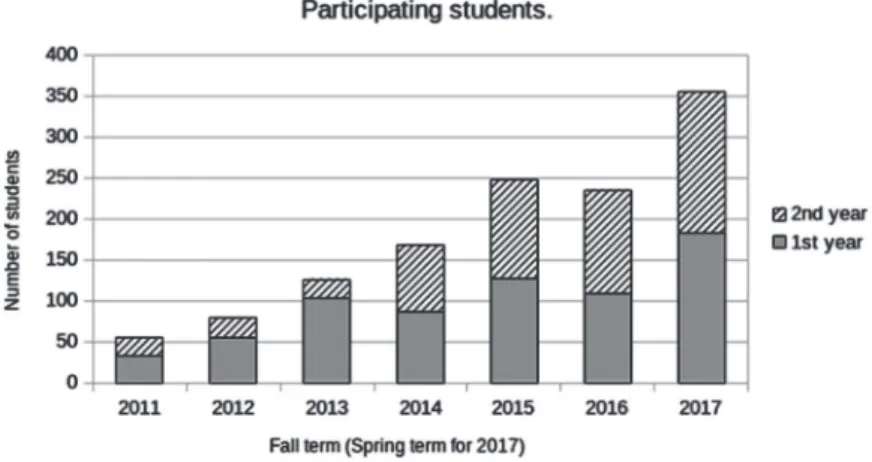

The ER program started in the fall 2011 semester with one 1st year and one 2nd year section, a total of 54 students. By spring 2017, all students (7 first year sections and 6 second year sections) had an ER component as part of their class (Figure 1). In 2011, there were fewer than 500 graded readers on campus with none in the library. There were also no leveled readers. Through the Special Education Fund (特別教育費) and the cooperation of the library, the ER collection has grown to match.

The university’s collection of ER materials now consists of over 600 books in the library and well over 1000 books in the hands of the English teachers. The books are split fairly evenly between leveled readers and graded readers with a few (less than 30) unsimplified texts for L1 children such as picture books and chapter books also available. The majority of the books are considered quite easy (YL<1.5). With over 1600 books, there were four to five books for each potential participant this past term which exceeds the recommended minimum of three books. This gives our students a reasonable opportunity to choose easy books that they want to read. Currently, there are three teachers who use ER in the classroom, and each teacher is responsible for the ER implementation details in their classroom. All teachers expect the students to do some SSR, and the reading is an assessed part of the English courses. For monitoring the reading, a mix of book logs and an on-line quiz system are used. The quiz system used is the Moodle Reader module which is a free and open source software plug-in for the Moodle learning management system, also free and open source software; for more about the Reader module, see Robb and Kano (2012, which is written in Japanese). All teachers use the Reader module which is installed on the university’s Moodle site (moodle.hkg.ac.jp) and provides short quizzes of 10 questions, mostly multiple choice and true/false problems, for the books in the ER collection.

3.2 Reading goals and assessment

Earlier in this paper three essential principles of ER were stated. The second, learners read as much as possible, is perhaps the most problematic. As teachers, we have provided many easy books that students can choose from, but the students are the ones who must read. The task of the teacher is to set fair and reasonable reading goals. Goals that allow students to improve their English proficiency and that are also achievable. If the students are unable to achieve the goal then it is unlikely that they will read as much as possible.

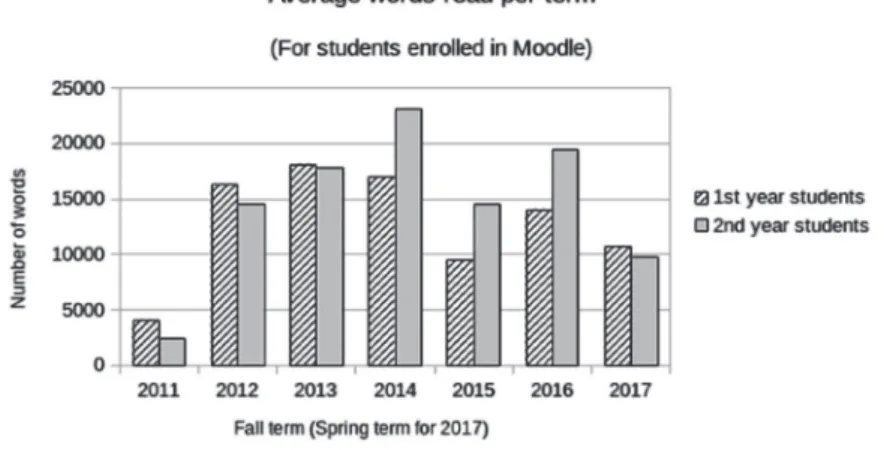

When first starting the program in 2011, there were only two classes and the students were told to read as much as possible with no fixed goal. The results were disappointing: 1st year students read an average of 4081 words and the 2nd year students read an average of 2439 words (see Figure 4 below). It was decided that the students needed a clearly defined reading goal that was fair and achievable, yet still challenging.

So how do we set a fair reading goal? The ER research cited in section 2.3 indicates that students need to read on the order of hundreds of thousands of words in a year to obtain measurable proficiency gains. Assuming that a student can read at a rate of 100 words per minute, 200,000 words would require 2000 minutes of reading over a year. That is over 30 hours of reading. Classroom time for a general English course at our university is 22.5 hours each term (15 classes multiplied by 1.5 hours per class) or 45 hours in an academic year. Without the ER becoming homework, a goal of 200,000 words is impossible.

would score below 300 on the TOEIC) and have little experience with ER (Figures 2 and 3) with about 60% of the students having never read an ER book before university, so we feel it is likely that a reading rate 100 wpm is probably fair for only our best students. For our weakest students, a rate of 50 wpm is more realistic. The students are expected to do 10 to 15 minutes of SSR reading during class-time, so the reading goals for one term might look like the following:

Students Reading rate SSR time Number of classes Reading goal Weakest 50 wpm × 10 minutes × 12 = 7500 words Strongest 100 wpm × 15 minutes × 12 = 18000 words However, students are encouraged to

exceed the set goals. Every term there are a few students who read on the order of 50,000 or 100,000 words. For example in Spring 2017, there were four students who read more than 50,000 words with the top reader having read 52,627 words as measured by the Moodle Reader module.

For assessment, the extensive reading done by students typically is between 20−30% of the grade assigned for the course. However, the weighting for the ER is dependent on each individual teacher. If success is measured by having students reading more words, then weighting the reading portion of the total grade heavily (30% or even more) will provide extrinsic motivation for many students to meet the goal or possibly exceed it signifi cantly.

3.3 Participation in and outcomes for the program.

Since 2011, the number of students participating in the ER program has grown from 54 to over 300 in the spring of 2017. Figure 1 shows the number students who were enrolled in the school Moodle website for each fall term since 2011; however, we should note that each of the figures may not reflect all students who did ER. As each teacher is responsible for the ER program in their classroom, Moodle Reader use has not been consistent across all classes. In

Figure 2 ER questionnaire, item 1(2016)

some classes Moodle Reader use was not mandatory and students may have kept book logs instead of or in addition to Moodle Reader.

Figure 4 shows the average number of words read for all students enrolled in the school Moodle from 2011 to 2017. The average for 2015 is noticeably lower than both the previous and the following year. There were two reasons for this:

1 .the program expanded in size, adding many lower level students to the program, 2 .for the two highest level classes, Moodle Reader use was optional.

In general, as our program has expanded to include more and more weaker students, the average words read has declined because the weaker students are expected to read less; weaker students usually have goals of less than 10,000 words and the strongest students sometimes have goals greater than 20,000. Since higher-level students dominated the ER program for the 2012︲14 cohorts, the amounts read tended to be higher.

We feel it is worthwhile to expand the program even though the weaker students are expected to read less than 10,000 words for two reasons. The fi rst is that 10,000 words is quite a lot of reading for our students. Our weakest students are typically at a junior high school level of understanding of English, and 10,000 words of fi ction and non-fi ction reading in a four month university term probably exceeds the total of similar reading done in all three years of junior high school. The second is to cast a wider net by including weaker students. All students

Figure 4 Average words read per term

should have the opportunity that extensive reading aff ords, and some weaker students actually enjoy ER and read more than stronger students.

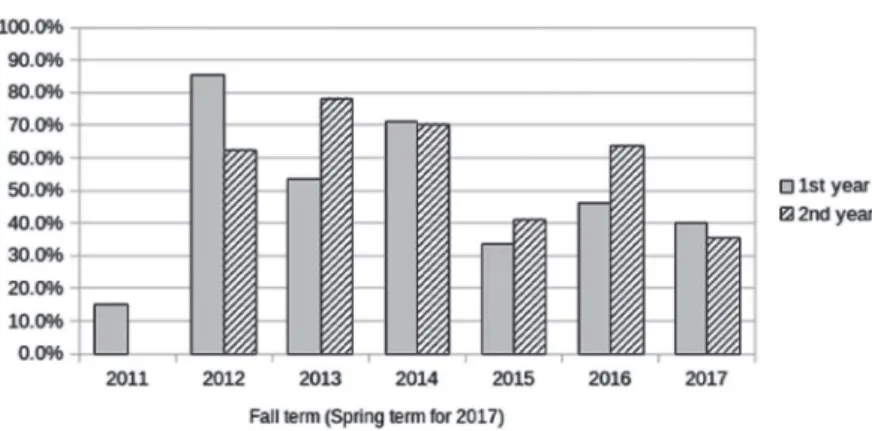

To evaluate how successful the Moodle Reader ER program is, it may be instructive to look at data for only those students who read more than 10,000 words. This group of students would include low level students who exceed the reading goals set for them and would also exclude higher level students who choose not to do extensive reading. Looking at Figure 5, we can see that as the ER program has expanded, the raw number of students in this group has increased. Not unexpectedly, the percentage of students who read more than 10,000 words has declined since 2015(Figure 6). This is mostly due to the increase in lower level students, but is also due in part to larger class sizes for the 2017 academic year. Reading goals have been lowered to accommodate weaker students who have been placed in a higher level class than they would have been in previous years. Since most students read to the goal, if the goal is lowered many students will read less than they are capable of.

Figure 7 shows the reading to goal for the 2016 cohort: the average words read dropped from 23,191 words (1st year, spring 2016) to 20,960(2nd year, spring 2017). The goal for the highest level class, which went from 22 to 29 students, dropped from 25,000 words to 20,000 with the average words read dropping from 27,157 to 22,352 mirroring the 5000 word drop in the goal.

Figure 6 students who read more than 10000 words

As stated earlier, reading amounts on the order of hundreds of thousands of words are usually necessary for measurable gains in reading proficiency, so we have not made any attempts to measure reading proficiency gains. We do have some students who have been top readers and also shown improvement in their TOEIC scores. One student, who read over 370,000 words, went from an initial TOEIC score of 295 to a final score of 630 over three years later. Another student, who read over 140,000 words in two years, improved to 540 points at the end of the second year after scoring 435 at end of the first. Without data, we are only speculating, but ER may help some students perform better on the TOEIC by allowing them to concentrate longer through the test. If students have done a lot of ER, they may be able read more of the test, more quickly.

4.What do the students think?

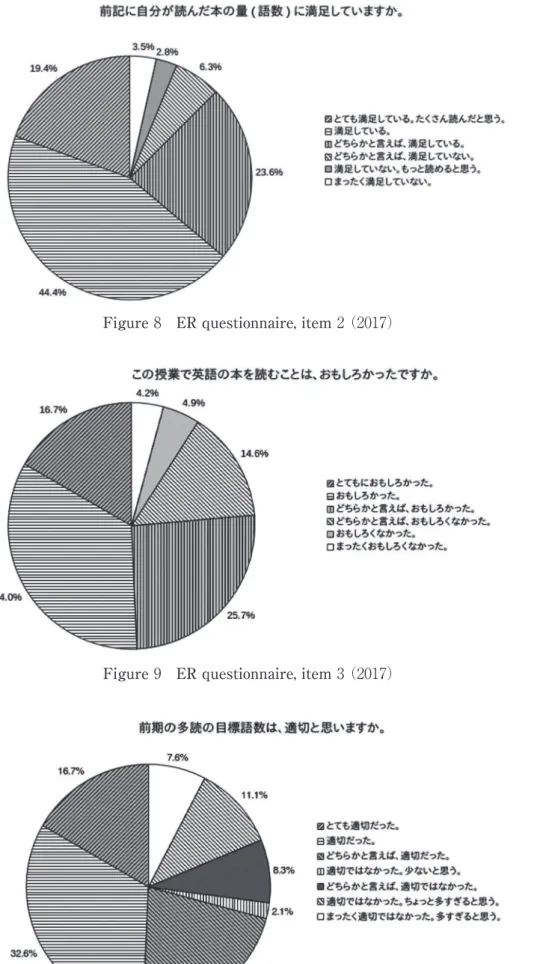

Part of the argument for extensive reading is that it can be enjoyable for students and positively effect affective variables such as self-confidence and motivation. As students read more, they gain confidence in their reading. Some students find the reading enjoyable which means ER can be intrinsically motivating. Since 2016, we have done a small survey to determine our students’ general attitudes towards ER. For Spring 2016, the survey was done with paper and pencil with 205 first and second year students. From Fall 2016, the survey questions have been administered on-line using the Moodle Feedback activity. All questions were given in Japanese and most were 6-point Likert items to force students away from choosing neutral answers.

As mentioned earlier, most of our students have little experience with ER before they come to university. For 205 students surveyed at the end of the spring 2016 term, over two-thirds had never read any English books before they came to university (Figure 2); the smaller survey in spring 2017 found that almost 60% of the students had not read any English books (Figure 3). So it is quite likely that ER is a novel experience for the students.

In July 2017, 144 students answered the following three questions on-line: • Are you satisfied with the amount of reading (words) that you have done? • Was it enjoyable reading English books in this class?

• Was the spring term reading goal fair and appropriate?

Figure 8 ER questionnaire, item 2(2017)

Figure 9 ER questionnaire, item 3(2017)

So for many of our students, extensive reading appears to be a positive experience. It is a source of satisfaction and can be interesting. As well, although the amount of reading can be demanding for our students, few of them find the amount unfair. In fact, the experience of ER may help some students lower their affective filter by reducing anxiety when confronted with a long English text to be read and increasing their confidence that they can read English. As one student wrote about ER when answering an exam question about her experience in first year at university:

And I feel grow myself. I can’t read long sentence (English) and write. But now I can. I think that thanks to lot of reading books. I’m really lots of read books. So next term have to keep reading many books. [sic]

5.Conclusion

At our university, we have tried to implement an ER program that allows students to read a large yet achievable amount of easily comprehensible English with the main goal being trying to positively effect affective variables such as motivation and anxiety towards English. The program has grown to include all first and second year classes. Although not all students participate, most students who do participate find the ER an interesting and satisfying experience.

Looking to the future, there are a number goals to work towards. On one hand, decreasing the number of students who choose not to participate could be done by better informing students of the benefits of ER, trying to cultivate an attitude of active learning towards English by them, and maintaining a more consistent ER program across the teachers. On the other, having cast a fairly wide ER net, we would like those students who have been caught in the net and have excelled to have more opportunities to do ER as they continue their education. An ER component added to some elective English courses may be an effective means to this end.

References

Beglar, David and Hunt, Alan (2014). Pleasure reading and reading rate gains, Reading in a Foreign Language Vol 26 Issue 1, pages 29︲48.

Day, Richard and Bamford, Julian (2002). Top ten principles for teaching extensive reading, Reading in a Foreign Language Vol 14 Issue 2, pages 136︲141.

Day, Richard and Bamford, Julian (1998). Extensive Reading in the Second Language Classroom. Cambridge University Press.

Elley, W. B. and Mangubhai, F. (1981). The impact of a book ood in Fiji primary schools. New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Extensive Reading Foundation (2011). Guide to Extensive Reading. www.erfoundation.org (retrieved 11 September 2017)

Reading in Japan Volume 1 Number 2.

Krashen, Stephen (1982). Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition. Pergamon Press Inc. (First printed edition) http://www.sdkrashen.com/content/books/principles_and_ practice.pdf (retrieved 5 September 2017)

Nation, Paul and Waring, Rob (2013). Extensive Reading and Graded Readers. Compass Publishing.

Nishizawa Hitoshi and Yoshioka Takayoshi (2016). Longitudinal Case Study of a 7-year Long ER Program, Proceedings of the rd World Congress on Extensive Reading Chapter 4. (retrieved 7 September 2017)