Factors Predicting Motivational Intensity in

Japanese EFL Engineering Majors

著者

Noriko IWAMOTO

著者別名

岩本 典子

雑誌名

Factors Predicting Motivational Intensity in

Japanese EFL Engineering Majors

号

15

ページ

17-30

発行年

2013-03

URL

http://id.nii.ac.jp/1060/00004207/

Creative Commons : 表示 - 非営利 - 改変禁止

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/deed.ja

Factors Predicting Motivational Intensity

in Japanese EFL Engineering Majors

Noriko nvAMOTO

*

In Japan, most high school students, regardless of the majors they choose. are required to take English ex-aminations to enter the university.

Thus, English is considered one of the most important subjects in highschool and many high school students have great motivation to improve their English, especially in their thirdyear

(Hayashi, 2005). However, after completing the entrance e χamination , many, especially non-English ma-jors,

are likely to lose their motivation to study English. For example, Berwick and Ross (1998)state that afterbeing admitted to the university, Japanese students are often left with “a motivational vacuum." Hayashi (2005)and Sawyer

(2007)also report a decrease in university students' motivational intensity toward learning Englishbecause students are more interested in their major subjects and/or extracurricular activities 。

However, English is important in the present internationalized society. and to acquire a second language,learners need to make substantial and continuous effort. What,

then, stimulates non-English majors to make ef-forts to improve their English proficiency after completing their entrance e χaminations? In this study, l e χam-ined 3

15 engineering majors and investigated the psychological factors that predict Motivational Intensity.

Literature Review

Since Gardner and Lambert's (1959)L 2 motivational research, much attention has been paid to psycho-logical factors and L 2 learning. Many studies have investigated the relationship between motivation and

learn-ing outcomes such as test scores or course grades. However, Domyei (2001)argues that motivation is indirectlyrelated to learning outcomes because the L 2 proficiency of a learner is likely to be influenced by the learner's

language aptitude and past learning e χperience. Moreover, Csizer and Dornyei (2005)state, "motivation is aconcept that explains why people behave as they do rather than how successful their behavior will be" (p.2O)

and emphasize the importance of e χamining motivational factors in light of motivated language behavior 。

In the Japanese context, many studies have been conducted to e χamine the relationship between L 2

affec-* An associate professor in the Faculty of Science and Engineering, and a member of the Institute of Human Sciences at Toyo University

18 東 洋 大 学 人 間 科 学 総 合研 究所 紀 要 第15 号 (2013 )

tive variables and learning outcomes, some of which included the relationship between L 2 affective variablesand the learners' motivated learning behavior. For example, Yamashiro and Sakai (1999)studied 141 juniorcollege students majoring in English and found that although students had positive attitudes and

a slight degree

of motivation to learn English, they reported making little effort. Sawaki (1997)examined 57 English andAmerican literature majors at a

Japanese women's university. A stepwise multiple regression analysis indicated that four factors, Use of English for Academic Purposes and Desire for Knowledge, Significance of English

Pro-ficiency for Real-life Communication, Desire to Pursue Career/academic Goals Abroad, and Interest in Pop Cul-ture, predicted Motivational Strength, which comprised the personal value of and the effort made toward study-ing English. Yashima (2000)investigated 389 Japanese students majoring in informatics at a

Japanese

univer-sity. A stepwise multiple regression analysis showed that good predictors of Motivation that describes havingdesire and making efforts to improve English proficiency were Instrumental Orientation (

β=.47,ρ<.001)' andIntercultural Friendship Orientation (P=.40,

ρ<.001). Honda and Sakyu (2004)considered 465 non-English ma-jors

(216 were studying the humanities or social sciences, and 239 were majoring in the natural sciences). Astepwise

regression analysis revealed that two orientations. Integrative Orientation (β=.42, p <.01)and Respect&

Influence Orientation (j3=.24,p<.01), best predicted Motivational Intensity. Honda (2005)found that predic-tors of Motivational Intensity differed between English majors (132 junior college

students)and non-English

ma-jors (455 university students). The best predictor of Motivational Intensity for English majors was Accomplish-ment

(29%), while that for non-English majors was Friendship (27%).

Research Questions

As shown above, the factors predicting the effort that the students make toward studying English appear to vary according to the context. In this study. l focus on engineering majors, who tend to be less interested in

Ian-guage study than those in the humanities. Two research questions are examined in this study : (l )"WhatL 2 af-fective factors can be found among this population sample?" (2 )"Which factors predict the participants' motiva-tional intensity?"

Method Participants

The participants were 315 first-year Japanese university students (271 males and 44 females)majoring in

engineering. All the participants were Japanese nationals and no returnees were included in this study. There-fore,

Instruments

A 50-item fixed-response questionnaire was used to measure the participants' attitudes and motivation to-ward learning English. This questionnaire was based on Gardner's (1985)Attitude/Motivation Test Battery(AMTB)and Horwitz et al.'s (1986)Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety scale (FLCAS).

Moreover, someitems were adapted

from Gardner, Tremblay, and Masgoret (1997), Yashima (2002), and Irie (2005).The origi-nal Japanese version of the questionnaire used in this study is presented in Appendi χ A and its English transla-tion

(along with the mean scores and standard deviations)appears in Appendix B. The participants answeredeach question using a si

χ-point Likert scale where : l =Strongly Disagree, 2=Disagree ,3=Slightly Disagree, 4 =Slightly

Agree, 5=Agree, and 6 =Strongly Agree.

Procedure

The students in English classes who voluntarily agreed to participate in the study completed the

question-naire listed in Appendix A in May, 2011. The data were subjected to factor analysis using SPSS 18.0, which as-certains some variables from

the analysis. To e χamine the construct validity of each variable, the Rasch meas-urement model was employed through Winsteps 3.70. Ne χt, a stepwise multiple regression analysis was con-ducted

; the dependent variable was Motivational Intensity, or self-reported effort, and the independent variableswere the L 2 affective variables found in the first research question. The alpha level" for statistical significance

was set at 。05.

Results

First, a descriptive analysis was conducted for the questionnaire items. Appendiχ B reveals the mean andstandard deviation for each item. The items with

the two highest mean scores were Item 10 (M =AM)(Not onlyliterature students

but also engineering majors should improve their English abilities)and Item 43 (訂 =4.95)(English is

necessary in today' s internationalized world). This seems to indicate that many students believeEnglish to be important and feel a need to improve their English abilities. The items with the two lowest meanscores were Item 34 (

ぼ=2.47)(/ want to work in an internationa/organization such as the United Nations) andItem 23 (訂 =2.57)(/ study English on my own beyond my English coursework) 。

Now, let us consider the first research question. "What L 2 psychological factors can be found among thispopulation sample?" This question was investigated by analyzing the dimensionality of the 50 questionnaireitems using a principal axis factor analysis with a varimax rotation (Brown,

2010, pp. 19-23). Items 3, 11, and44 were

deleted because they loaded below 。40 on all factors. Items 30, 32, and 40 were comple χ : Item 30loaded on

Factor 2 at. 45 and Factor 5 at 。46, Item 32 loaded on Factor l at 。47 and Factor 2 at .56,and Item 40loaded on Factor l

東 洋 大 学 人 間科 学 総 合研 究 所 紀 要 第15 号 (2013 )

20

Table 1. Factor Loadings from a Principal-Axis Factoring ofthe Questionnaire Items

Factor communality 6 5 4 3 2 1 68629015074336147066666656675645255434 2954453016555202 II ● l a 一 l 一 . . . 一 4 2 7 4 6 8 1 1 1 1 0 2 52 383563456980230010 11 01 ・ 一 . 一 . . ∼ . 一 . . 一 . . . 7 0 2 4 4 3 051310 18393819004165520 111 01000000022301 . . . 一 . 一 . 一 . ・ . ・ . 一 . 四 . ・ I . 一 . . 71 52498355504268056532 33364465766644544653 852243372857235233353 100000201020100231000 . ・ . ・ . 一 . . . . . . . . . . 一 . . ・ ・ . . 一 四 6686253943495182037842000101000 111 30455654 ・ 一 一 一一 − ・ l l l l l 一 I I I ● ・ ・ e ● ・ 437388170000946713035906113341222300212010000000664557555001 ・ . . . . . ・ . . ﹃ . . ・ . . ﹄. 一 . . ・ ・ . 参 一 I − I I ● ・ ● l l l 668064040536109150645200120 100010177575676500000 II ︲ . 一 . 一 . ・ . ・一 一 一 一 . 一 . 一 . ● 9 一 一 一 一 I I 一 一一 一 一・ . . 一 . ’ . 3173627261246186 1422766770000001 Φ 一 ■ ■ ・ e 一 一 ・ 一 一 一 . 一 . 一 . 一 . 一 . 2199083308437133332122200000 . ・ . . . . ・ . . 一 . . . . 一 . 2052 11 02 201613010409・ . 一 . . 一 一一 -.10 -.08 -.04 52290300727937415001001212 11 020121 一 . 一 . ﹃ . 一 一 一・ . . . ・ . . . . S 一 I Φ 12 10 16 16 9 4 4 0 1 r s i 122071059795 111 000865768 . ・ . . 四 ∼ 一 一 参 一 ・ ・ .66 .18 Item-Item l Item 2 Item 4 Item 5 Item 6 Item 7 Item 8 Item g Item 10 Item 12 Item 13 Item 14 Item 15 Item 16 Item 17 Item 18 Item 19 Item 20 Item 21 Item 22 Item 23 Item 24 Item 25 Item 26 Item 27 Item 28 Item 29 Item 31 Item 33 Item 34 Item!35 Item 36 Item 37 Item 38 11 4 1 6 1 5 1 0 0 3 2 Item 39 .75 .11 -.10 Item 41 .73 .16 -.10 .16 .13 .14 .31 3870835100000000 一 . 一 . 一 . ﹃ . ・ ∼ 一 . 一 . 8 4 0 3 6 4 一 ・ ︱ ぐJ Item 42Item 43 Item 45 .12 Item 46 。10 .11 5 2 4 3 3 2 2 1 7 7 3 3 0 3 3 1 Item!47 Item 48 Item 49Item 50

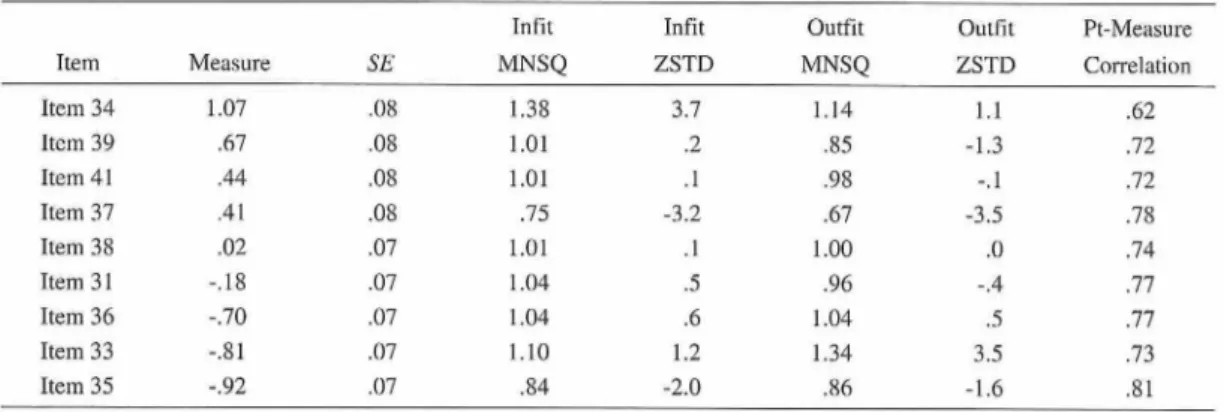

The first factor accounts for 14.2% of the item variance. with the 10 items loading on this factor : Items 3 1,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,41,

飢d42. These items are thought to indicate the students' interest in foreign peopleand cultures and the desire to go abroad, which Yashima (2002)called International Posture. Therefore, Factorl was labeled

“International Posture." The Rasch measurement model was employed to examine the constmctvalidity. Linacre

(2007)suggested that Infit and Outfit MNSQ statistics of .50-1.5 are considered an indicationof a good item fit. After conducting a Rasch analysis with 10 items, Item 42 (/ study English because it is coolto be able to speak English)misfit the Rasch model :

Infit MNSQ was 1.39 and Outfit MNSQ was 1.95. An ex-amination of the contents of Item 42 suggested that this item does not necessarily represent the students' intema-tional orientation. Thus, this item was deleted. and the Rasch analysis was conducted again with the remainingnine items.

Table 2 shows that all the items met the criterion. Moreover, the second column displays itemmeasures,

which indicate the item difficulty for each item ; the greater the value, the more difficult it is to en-dorse the item.

The item difficulty measures seem to indicate that many students are interested in English-speaking people and cultures (Items 33, 35, and 36), while only those with greater international posture want towork abroad in the future (Item 34).

Table 2. Rasch Item Statistics for the International Posture Items

Item Item 34 Item 39 Item 41 Item 37 Item 38 Item 31 Item 36 Item 33 Item 35 Measure 774128012064401789 刄 8 8 8 8 7 7 7 7 7 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Infit MNSQ 8 1 1 5 1 4 4 0 4 3 0 0 7 0 0 0 1 8 一 I I ■ ■ Φ I S 摯 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 Infit ZSTD 7 2 1 2 1 5 6 2 0 S I Φ 一 春 S l Φ 一 3 3 1 2 Outfit MNSQ 148598670096043486 1 1 11 Outfit ZSTD 131504556 11 ・ 3 一 31 一 一 一 Pt-Measure Correlation 6272 2 8 4 7 7 3 1 フ フ フ フ フ フ 8

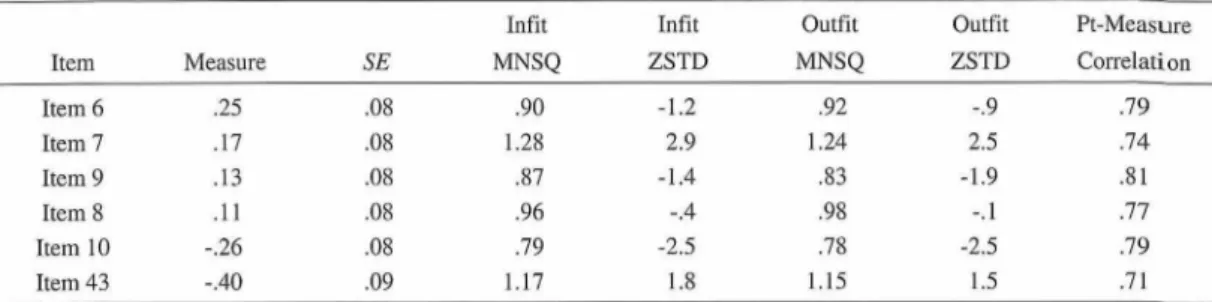

The second factor, which consists of six items. accounts for 9.6% of the item variance. These are Items 6,7,

8, 9, 10, and 43. The seven items were put into the Rasch analysis. and the results show that no items misfitthe Rasch model (see Table 3). These items were related to the students' recognition of the importance of Eng-lish in Japan. Therefore, Factor 2 was labeled “Importance of English." Many students think that English is im-portant

(Item 43)and that they need to improve their English abilities (Item 10).0n the other hand, Item 6 (/absolutely believe that English should be taught at the university)was the most difficult item to endorse in thisconstruct.

The third factor, which accounts for 9.4% of the item variance, consists of nine items. In the Rasch analy-sis, all the items met the criterion (see Table 4). These items represent the anxiety that students feel in the

Eng-22 東 洋 大 学 人 間 科 学 総 合研 究所 紀 要 第15 号(2013)

Table 3. Rasch Item Statistics for the Importance of English Items

Item-Item 6 Item 7 Item 9Item 8 Item 10 Item 43 Measure 5731602 111 24 . ・ . . 一 . 一・ 認 8 8 8 8 8 0 ノ 0 0 0 0 0 0

Infit

MNSQ-.90

87 /OO ノ7fN 00 O ノ711 I Infit ZSTD 294458 1CN -H I ro -H Outfit MNSQ-.92 1.24 3880 ノ .78 1.15 Outfit ZSTD C T \ i n 一 2 -1.9 -.1 -2.5 1.5 Pt-Measure Correlation 9 4 1 r -- c -o 077

79

71

lish class. Thus, Factor 3 was labeled “Language Anxiety." The item difficulty measures reveal that many stu-dents are likely to worry about English class exams and grades (Items 13 and 14),

while only those who havegreater anxiety face difficulty in understanding English (Item 16).

Table 4. Rasch Item Statistics for the Language Anxiety

Item Item 16 Item 18 Item 15 Item 20 Item 19 Item 17 Item 12 Item 14 Item 13 Measure 344493339860001344 SE 7 7 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Infit MNSQ 138799140792902581 1 II I

Items-Infit

ZSTD

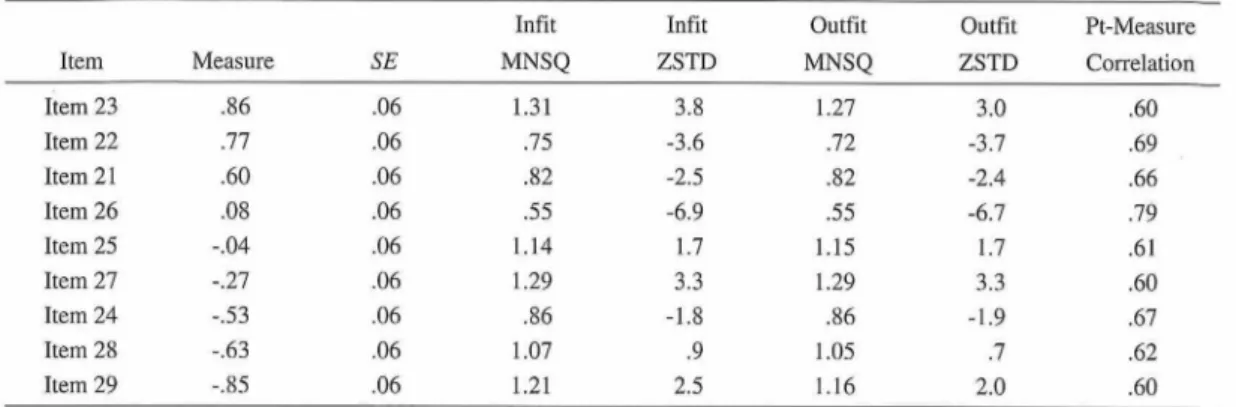

571 11 一 7 9 1 3 1 7 Φ 一 一 一 曾 4 1 1 1 3 r ^ J ・ 一 一 Outfit MNSQ 5080 180 ノr-jI I 8780 ノ00a \ a ノ(N OOI I Outfit ZSTD 63239333 \c>ICM I CNl 一 一 3 り 乙 一 一 Pt-Measure Correlation 5 8 7 0 5 6 1 4 5 6 6 6 6 6 7 / ○ 73The fourth factor, comprising 8.7% of the item variance, includes nine items : Items 21 to 29. All the itemsmet the criterion in the Rasch analysis (see Table 5). These items represent students' eff)rts to improve theirEnglish abilities, and therefore Factor 4 was labeled “Motivational Intensity." From the item difficulty meas-ures,

many students reported that they do English homework and study for quizzes and tests (Items 28 and 29) ・On

the other hand. only those with greater motivational intensity reported studying English beyond their course-work (Item 23).

The fifth factor, which accounts for 5.7% of the item variance, consists of six items, Items 45, 46, 47, 48,49,

and 50. In the Rasch analysis, all the items met the criterion (see Table 6). These items represent instrumen-tal purooses for studying English. Thus, Factor 5 was labeled “Instrumental Orientation." The item difficultymeasures

reveal that many students are likely to agree that they study English to gain knowledge and help insearching for a job (Ite

万ms 45 and 47), while few students agreed that they study English to acquii サe informationfrom books and websites in English (Item 50).

Table 5. Rasch Item Statistics for the Motivational Intensity Items Item Item 23 Item 22 Item 21 Item 26 Item 25 Item 27 Item 24 Item 28 Item 29 Measure 867760080427536385 . . 四 . 一 . 一 . 一 . 一 . 一 . 認 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Infit MNSQ 152549671378512802 1 II II

Table 6. Rasch Item Statistics for the Instrumental

Item Item 50 Item 46 Item 49Item 48Item 47Item 45 Measure 643994 321034 茫 6 6 6 6 6 丿 ○ 0 0 0 0 0 0

Infit

MNSQ-1.20

80675 1 ︵ リ70 ノ0 ノ ー Infit ZSTD 865973895 3326131 2 Motivation Items Infit ZSTD 5 c ノ ‘ 3 ( N ( N ︱ I 346 3 一 一 ︲ Outfit MNSQ 7 2 2 5 5 9 6 2 7 8 5 1 2 8 a 希 Φ 一 ■ I I I I I 1.05 1.16 Outfit MNSQ-1.32 98465 1870 \ O^I Outfit ZSTD -3.0 -3.7 -2.4 -6.7 73970 131 rsi Outfit ZSTD 634446 3213 一 ︻ 一 一 Pt-Measure Correlation 0 9 6 9 1 0 7 2 0 6 6 6 7 6 6 6 6 6 Pt-Measure Correlation 5 8 3 6 2 0 6 6 7 7 7 7The si χth factor accounts for 5.1% of the item variance, with four items loading on this factor : Items 1, 2,4,

and 5. The Rasch measurement model was employed to e χamine the construct validity. Table 7 shows allitems that met the criterion. These items indicate students' positive attitude toward learning English. Therefore,Factor 6 was labeled

“Positive Attitude toward Learning English." The item easiest to endorse was Item 2 (/would take English class even if it were not required), while the item most difficult to endorse was Item 5 (/wish

we had more English classes).

Table 7. Rasch Item Statistics for the Positive Attitude

Item-Item 5 Item l Item 4Item 2 Measure 8 / n ︶ / n ︶ 8 8 1 ︷ Z 7 茫 87770000 Infit MNSQ 3 5 4 6 0 9 7 2 一 S I 春 1 1

toward Learning English Items

Infit ZSTD 3640 一 33 Outfit MNSQ 35500972 1 1 Outfit ZSTD 3 /0 り 乙3 一 3 り 乙 Pt-Measure Correlation 1 5 8 8 8 5 8 8

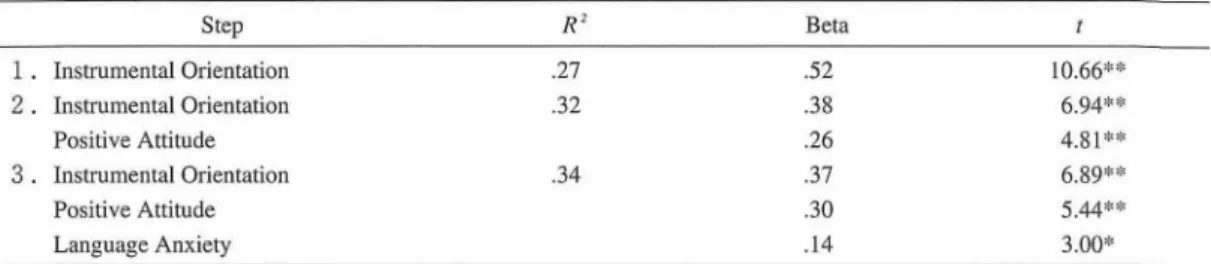

Now let us turn our attention to the second research question. “Which factors predict the participants' moti-vational intensity? ” This question was examined by conducting a stepwise multiple regression analysis with all

24 東 洋 大学 人 間科 学 総 合 研 究 所 紀 要 第15 号(2013 )

five variables as predictors. The result indicated that three variables, Instrumental Orientation, Positive Attitude,and Language Anxiety, are predictors of Motivational Intensity (Table 8).

Table 8. Multiple Regression Predicting Motivational Intensity from Affective Variables

Step 1 . Instrumental Orientation2

. Instrumental OrientationPositive Attitude

3 . Instrumental OrientationPositive Attitude

Language Anxiety **p<.01, *ρ<.05,F-52A1 μ<.001) だ 72 423 3 Beta 2 8 6 7 0 4 5 3 2 3 3 1 「 10.66** 6.94** 4.81** 6.89** 5.44** 3.00* Discuss 工on

The present study investigated predictors of Motivational Intensity in 315 engineering students. Six factorswere extracted from the questionnaire : Positive Attitude toward Learning English, Language Anxiety, Intema-tional Posture, Instrumental Orientation, Importance of English, and Motivational Intensity. The results of astepwise

multiple regression analysis revealed that there were three predictors of Motivational Intensity. The best predictor was Instrumental Orientation, which indicates that presenting engineering students with clear

ideas of the usefulness of English can motivate them to study the language. The ne χt strong predictor was Posi-tive Attitude toward Learning English. The students' feelings that they like and want t0 learn English seem to

lead to their motivated language behavior. Finally, to a lesser eχtent, Language An χiety predicted MotivationalIntensity. Usually, anxiety is thought to be deterrent t0 language learning ; however, in this study, having anxi-ety toward the English language and an English class appears to lead a student

to make an effort to study Eng-lish 。

On the other hand. Importance of English and International Posture did not significantly predict Motiva-tional Intensity. The result that Importance of English did not predict motivated language behavior is similar to

Yashima (2002), in which Vague Sense of Necessity had no significant relations with motivation or proficiency.This variable represents that students vaguely recognize the importance of English but lack a clear idea of howthey will use it. Likewise,

engineering students in this study also know that English is very important in the pre-sent globalized society, but this recognition alone does not lead them to make an effort to learn English. Instead ,giving

them a clearer idea of how they can use English is more effective. as Instrumental Orientation was the best predictor of Motivational Intensity 。

In this study, International Posture, students' interest in foreign people and cultures. did not lead to self-reported effort ; however, in some studies. this is an important predictor. For e χample, in Honda and Sakyu(2004),

Inter-cultural Friendship, representing interest in foreign cultures and a willingness to interact with foreign people, was the second-best predictor. The present study's result that International Posture did not predict Motivational Intensity suggests that participants were not interested in foreign people and cultures as were those in other stud-ies, and therefore they were less likely to study English for integrative purposes.

Conclusion

The findings of this study show that the motivated language behavior of engineering students can be

pre-dieted by Instrumental Orientation, Positive Attitude toward Learning English, and Language An χiety. 0n theother hand, Importance of English

and International Posture were not significantly strong predictors of Motiva-tional Intensity. However, it should be noted that the participants were all engineering majors, and therefore the results should be generalized with caution to other contexts. Moreover,English proficiency of most participants

was at 10w or intermediate levels ; therefore, the results may not be applicable to students with much higher orlower proficiency levels.

Despite these limitations, the present study suggests some important implications. To have students make an effort to learn English, telling them the instrumental purposes of using English is more effective than just

vaguely reminding them of the importance of English. Second, students' positive attitude toward English Ian-guage and class is very important. Finally, an χiety toward English does not necessarily have a detrimental ef-feet on students. It may,

in fact. help students make a greater effort to study English 。

The participants in this study were all freshmen who answered the questionnaire in May. Therefore, in fu-ture research,

it may be interesting to compare the results with those obtained when they are in their second and third years, as their attitude and motivation may change after studying English at the university for more than a year.

Notes

1. pis standardized beta values which reports the importance of each predictor in the model. The bigger ab-solute values are, the more important they are ・ p-values less than .05 are statistically significant (Field, 2005,p.197).

2. The alpha level is the level of significance set by the researcher for inferring the operation of nonchancefactors (Elfson et al., 1998,p.2O)

References

Berwick, R ・, & Ross, S. (1989). Motivation after matiiculation : Are Japanese learners of English still alive after eχam hell?JALT Journal, 月(2) ,193-210.

26 東 洋 大 学 人 間科 学 総 合 研 究 所 紀 要 第15 号 (2013 )

ter,14 (1), 19-23.

Csizer, K,, & Dornyei, Z. (2005). The internal structure of language learning motivation : Its relationship with languagechoice and learning effort. Modem Language Journal, S9 (1), 19-26.

Dornyei, Z. (1990). Conceptualizing motivation in foreign-language learning. Language Learning, 40(1), 45-78. Elifson,K ・,Runyon, R. P・, & Haber,A. (1998). Fundamentals of Social Statistics. McGraw-Hill.

Field, A. (2005).Discovering statistics using SPSS 。Thousand Oaks, CA : Sage Publications.

Gardner,R. C. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning:The role of attitude and motivation. London : Ed-ward Arnold.

Gardner, R. c, & Lambert, w. E. (1959). Motivational variables in second language acquisition. Canadian Journal of Psy一chology, /i ,266-272.

Gardner, R. C・, Tremblay, p. F・, & Masgoret, A. (1997). Towards a full model of second language learning : An empirical in-vestigation. Modem Language Journal, Si, 344-362.

Green, s. B., & Salkind, N. J. (2004). Using SPSS for windows ajid macintosh : Analyzing and understanding data. UpperHill River, NJ : Pearson Prentice Hall.

Hayashi, H. (2005). Identifying different motivational transitions of Japanese ESL learners using clusiter analysis : Self-determination perspectives. JACET Bulletin, 41 ,1-17.

Honda, K.(2005). Learner difference and diversity in intrinsic/extrinsic motivation among Japanese EFL learners. Memoirsof Osaka Kyoikii University, 54 (1), 23-46.

Honda, K., and Sakyu, M. (200 鮭A motivation-appraisal model for Japanese 万EFL learners : The rol万e万〇f orientations as moti-vational antecedents. Language Education & Techno/ogy, 41, 1-15.

Horwitz, E, K・, Horwitz, M. B・, &Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. Modern Language Journal, 70 ,125-・132.

Irie, K. (2005) 。Stability and flexibility of language learning motivation. Unpublished Doctorial Dissertation, Temple Univer-sity Japan, Tokyo, Japan.

Linacre, J. M. (2007). A user's guide to WINSTEPS : Rasch model computer program. Chicago : MESA.

Sawaki,Y. (1997). Japanese learners' language learning motivation : A preliminary study. JACET Bulletin, 28 ,83-96.

Sawyer, M. (2007). Motivation to learn a foreign language : Where does it come from. where does it go? Kotoba to Bunka[Language and Culture], 10 ,33-42 (Kwansei Gakuin University Language Center).

Yamashiro, A. D ・, &Sakai, M. (1999). The relationship among motivation, attitudes, and English language proficiency : Thecase of Saitama Junior College. Journal ofSaitama Junior College, s, 129-150.

Yashima,T.(2000) 。Orientations and motivation in foreign language learning : A study of Japanese college students. JACETBulletin, 31 ,121-133.

Yashima, T. (2002). Willingness to communicate in a second language : The Japanese EFL context. The Modern LanguageJournal, 86 (1), 54-66.

Appendix A. Original student Questionnaire 次 の 各 質 問 に つ い て 、あ な た 自 身 に ど の程 度 当 て は まる か 、尺 度 上 の該 当 す る 項 目 に○ を つ け て く だ さ い 。 1 2 3 4 5 6 全 くそ う 思 わ ない そ う 思 わ な い あ まり そ う 思 わな い や やそ う 思う そ う 思 う 強 く そ う 思 う 1 。 英 語 は 好 きな 科 目 で あ る。 2. 大 学 で 英 語 が 必 修 科 目 で な く て も 、英 語 の授 業 を受 講 す る と 思 う。 3. 自 分 が 習 い 始 め た 時 期 よ り も 、 も っ と 早 く か ら英 語 を 学 べ ば よ かっ た と 思 う。 4. 英 語 を 学 ぶ こ と は 楽 しい 。 5. も っ と 英 語 の 授 業 を 増 や し て 欲 し い。 6. 大 学 で 英 語 を 学 ぶ の は 当 然 だ と 思 っ て い る。 7. 将 来 成 功 す る た め に は 、 英 語 は 必 要 だ と 思 う。 8. 大 学 在 学 中 に、 英 語 の 力 を も っ と 伸 ば し たい と 思 っ て い る。 9. 英 語 を 習 得 し な け れ ば な ら な い と い う 気 持 ち が あ る 。 10. 文 系 の 学 生 だけ で な く 、 理 系 の 学 生 も 英 語 の力 を 伸 ば す 必 要 があ る と 思 う。 11. 自 分 より も他 の 学 生 の 方 が 英 語 が で きる とい つ も 思 っ て い る 。 12. 英 語 の クラ スで 、 自 分 が 先 生 に あ て ら れ る こ と が わ か る と 心 配 に な る。 13. 英 語 の ク ラ スの 試 験 の こ とを 考 え る と 不 安 に な る 。 14. 英 語 の単 位 を落 とし て し まう の で は な い か と 心 配 に な る 。 15. 英 語 の授 業 で とて も緊 張 し て 、 知 っ て い る こ と を 忘 れて し まう こ と が あ る 。 16. 英 語 の勉 強 をす れ ばす る ほ ど、 より わか ら な く な っ て し まう 。 17. 英 語 の ク ラ スで 自 ら進 んで 答 え を言 う なん て 恥 ず か し い 。 18. 他 の ク ラ ス より も英 語 の クラ ス の 方 が 、 ず っ と緊 張 し て ナ ーバ ス にな る 。 19. 他 の 学生 た ち の前 で 英 語 を話 す な んて 恥 ず か し い 。 20. 英 語 がで き る よう に な る た め に、 学 ば なけ れば な ら ない 規 則 の 多 さ に 圧 倒 さ れて し まう 。 21. 他 の 学生 と 比 較 し て、 私 は英 語 を一 生 懸命 勉 強 し て い る と思 う 。 22. 英 語 の 勉 強 に長 時 間費 や して い る。 23. 英 語 の授 業 の 課 題以 外 に も 自分 で 英 語 を勉 強し て い る。 24. 英 語 の授 業 に 集 中 し、 熱 心 に 取 り組 んで い る 。 25. 英 語 の授 業 で わ か ら ない こ と があ れ ば、 い つ も先 生 や友 達 に 聞 く よう に して い る。 26. 英 語 の力 を 伸 ば す た め に 、一 生 懸 命 勉 強し て い る 。 27. 英 語 の ク ラ ス で 、 宿 題 が 訂正 さ れ て 返 って き た ら 、い つ も き ち ん と 見直 し を し てい る。 28. 小 テ ス ト や 定 期 試 験 の 勉 強 を 一 生 懸 命 やっ てい る。 29. 英 語 の 宿 題 は い つ も き ち ん と や っ てい る。 30. 英 語 の 必 修 科 目 を 取 り 終 え て も 、英 語 の 勉 強 は 続 け るつ も り であ る。 31. 海 外 に住 んで み た い と 思 う。 32. ネ イテ ィブ スピ ーカ ーと 英 語 で コ ミ ュ ニ ケ ー シ ョ ン が と れ る よ う に な る の で 、 英 語 の 勉 強 は 大切 だ と 思 う。33. 英 語 圏 の 人 々 ( ア メ リ カ 人 や イギリ ス 人 な ど ) に 好 印 象 を 持 っ て い る 。 34. 国 連 の よう な国 際 的 な 組 織 で 働 い て み た い。 35. 英 語 圏 の 人 と友 達 にな り たい 。 36. 英 語 圏 の 文 化 に興 味 が あ る 。 37. 将 来 、 海 外 研 修 や 海 外 赴 任 ( ふ に ん) を し て み た い と思 う 。 38. 英 語 に 関 す る 世界 につ い て 学 び たい と思 う 。 39. 将 来 、 海外 に ひ ん ぱ ん に行 く よう な 仕 事 に 就 きた い 。 40. 外 国 の 人 だ ち と 自由 に交 流 で き る よう にな る の で 、 英 語 の 勉 強 は 大 切 だ と思 う 。

28 東 洋 大 学 人 間 科 学総 合研 究 所 紀 要 第15 号 (2013 ) 41. で きれ ば 留 学 し たい と思 っ て い る 。 42. 英 語 を し ゃ べ れ る とか っ こ い い の で 、 英 語 の 勉 強 は 大 切 だ と 思 う。 43. 英 語 は 今 日 の 国 際 社 会 で 必 要 な も の で あ る。 44. 英 語 を 勉 強 す る の は 単 位 を 取 る た め で あ る。 45. 教 養 を 高 め る た め に 、 英 語 を 勉 強 し てい る。 46. 英 検 やTOEIC な ど の検 定 試 験 の た め に英 語 を 勉 強 し て い る。 47. 英 語 が で き る と 就 職 に 有利 な ので 、英 語 を 勉 強 して い る 。 48. 海外 旅 行で 困 ら な い よ う に英 語 を 勉 強し てい る 。 49. 日本 国 内で 外 国 人 に 話 し か け ら れ た時 に、 困 ら ない よう に 英 語 を勉 強し て い る 。50. 英 語 の文 献 や ウ ェ ブ サ イト か ら情 報 を得 る ため に、 英 語 を 勉 強し て い る 。

Appendi χ B. An English Translation of the Questionnaire Items with Means and standard Deviations for the EntireSample

Questionnaire Items

1 . English is my favorite class.

2 . I would take English class even if it were not required. 3. I wish l had begun studying English earlier

4.1 enjoy learning English.

5. I wish we had more English classes.

6. I absolutely believe that English should be taught at university. 7 . English is a must for me to succeed in the future.

8. I want to improve my English ability while l am a university student. 9. I feel that l need to acquire English.

10. Not only literature students but also engineering majors should improve their English abilities.11. I keep thinking that my peers are better at English than l am.

12. I tremble at the thought that I'm going to be called on in English class. 13.1 worry about my English class e χams.

14. I worry about the consequences of failing my English class. 15. In English class, l get so nervous that l forget things l know 16. The more l study English, the more confused l get.

17. It embarrasses me to volunteer answers in my English classes. 18.1 get more nervous in English class than in other classes.

19. It embarrasses me to volunteer to answer in my English/Japanese class 20. I feel overwhelmed by the number of rules l have to learn to acquire English. 21. Compared to other students, l think l study English relatively hard. 22. I spend a lot of time studying English.

23. I study English on my own beyond my English coursework.

24. During my English classes l am absorbed in what is taught and concentrate on my studies. 25.When l have a problem understanding something what we are leaning in English class 。

l always ask the instructor or friends for help 26. I work hard to improve my English ability・

27. I always check my corrected assignments in my English course. 28. I study hard for quizzes and tests for English class 29. I always do my homework well.

30. I continue to study English/Japanese after l finish taking the required classes 31. I want to live in a foreign country

肛-3.30

3.84

4.25

3.54

2.89

4.64

4.67

4.70

4.70

4.88

4.49

3.94

4.09

4.01

3.57

2.91

3.75

3.04

3.71

3.69

2.79

2.64

2.57

3.79

3.36

3.25

3.56

3.88

4.06

3.90

3.19

SD-1.47

1.67

1.53

1.38

1.31

1.27

1.29

1.22

1.30

1.23

1.48

1.52

1.46

1.57

1.52

1.28

1.42

1.42

1.48

1.37

1.15

1.16

1.37

1.17

1.28 1.19 1.35 1.23 1.27 1. ∠141.7132. Studying English is important to me because it wi】1 allow me to communicate with native speakers of English.

33. I have a favorable impression toward English speaking people such as Americans and the British.34. I want to work in an international organization such as the United Nations

35. I want to make friends with English speaking people. 36. I am interested in the cultures of English speaking countries. 37. I want to temporarily work abroad in the future.

38. I would like to learn about the English-speaking world. 39. I would like to have a job in which l work overseas frequently.

40. Studying a foreign language is important to me because it will allow me to communicate more freely with people from other countries

41. I would like to study abroad if possible.

42. I study English because it is cool to be able to speak English. 43. English is necessary in today's internationalized world. 44. I study English to get credits to graduate.

45. I learn English to be more knowledgeable

46. I study English for an English proficiency test such as the STEP-Eiken or TOEIC. 47. I study English because l think it will be useful in getting a good job.

48. I study English to travel abroad

49. I study English so that l won't get embarrassed when l am spoken to be a foreigner in Japan・ 50.・I study English in order to get the information from English books or Web sites.

4.43

3.76

2.47

3.79

3.66

2.86

3.15

2.70

4.46

2.83

3.88

4.95

3.64

3.80

3.20

3.75

3.34

3.30

3.10

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 130

32

32

52

49

50

42

45

30

46

37

12

44

27

46

36

34

38

38

30 The Bulletin of the Institute of Human Sciences, Toyo University, No. 15

【Abstract

】

理 工 学 部 生 の英 語 習得 努 力 を も た ら す 要因 につ い て

岩 本 典 子 *

本 論 文 は、 理 工 学 部生315 名 を対 象 に、 彼 ら の 英 語 習 得 努 力 を も た ら す 要 因 につ い て 調 査 をお こ な っ た 。 ア ン ケ ー ト デ ー タ の 因 子 分 析 の 結 果 、「 英 語 学 習 に 対 す る 積 極 的 態 度」、「 言 語 不 安 」、「国 際 的 志 向 性」、「 道 具 的 動 機 」、「 英 語 の 重 要性 の認 識 」、「英 語 習 得 努 力 」 の6 つ の 要 因 が 抽 出 さ れ た。 次 に 、 英 語 習 得 努 力 を 従 属 変 数 、 そ の他 の 変 数 を 独 立変 数 と す る重 回 帰 分 析 を行 っ た 結 果 、「 道 具 的 動 機 」、「 英 語 学 習 に 対 す る 積 極 的 態 度 」、「 言 語 不 安 」 の3 つ の 変 数が 有 意 と なっ た。 つ ま り、 英 語 を 使 用 す る 具 体 的 な 目 的 を 理 解 し、 英 語 が 好 きで 学 習 し た い と い う 気 持 ち を 持 つ こ とが 、 学 生 の 努 力 の 要因 に なる こ と が 明 ら か に な っ た。 さ ら に、 英 語 の 授 業 や 言 語 に対 し て 不 安 感 を 持 つ こ と も、 英 語 学 習 につ なが る こ と が わか っ た 。 キ ーワ ード : 言 語 習 得 、 第二 言語 習 得 にお け る 情 意 要 因 、 第 二 言 語 習 得 努 力 、 第 二 言 語 習 得 の 動 機 、 言 語 不安This study investigated psychological factors in L 2 students that predict the motivational intensity, or the effort that learn-ers intend to exert in studying English, of315 engineering majors. Data reduction through factor analysis indicated siχ fac-tors :

Positive Attitude toward Learning English, Language An χiety, International Posture, Instrumental Orientation, Feelingsabout Importance of English, and Motivational Intensity. A stepwise multiple regression was conducted ; the dependent vari-able was Motivational Intensity, and the independent variables

were the other five affective factors. The results indicated that three variables-Instrumental Orientation, Positive Attitude, and Language Anxiety-were predictors of Motivational Intensity. Key words : language learning, affective factors in L 2 acquisition, motivational intensity, EFL motivation, foreign language anxiety