Yes-No Questions, Negative Yes-No Questions,

and Tag Questions:

Implications for Teaching Japanese Students of English

Michael V. Mielke 〈論文〉

Introduction

Learning English as a second language or foreign language poses many challenges for Japanese students, particularly in the use of correct English grammar. Various authors have shown that Japanese students make similar errors with many parts of English grammar (Barker 2008, Izzo 1999). Some errors can be relatively benign in their consequences such as forgetting the "s" at the end of third person singular verbs, or mistaking subject or object pronouns in constructions such as, "Me and her are going to the park." In these two common error examples, the meaning is still quite clear from the context. One area of grammar that can have more serious consequences is in what Huddleston and Pullum (2016, 853-855) refer to as closed interrogatives but more commonly known as yes-no questions, where the answers are either a yes or no (also referred to as polar questions (868)). The choice of answers is limited. Variations of closed interrogatives include tag questions, negative yes-no questions, and declarative statements, both positive and negative that serve as questions when they have rising intonation. These types of questions, especially closed negative interrogatives, require "an affirmative or negative reply - often just 'yes' or 'no' (Crystal 1995, 218) and thus if there is a misunderstanding about how to answer this seemingly simple question form, there is a high probability of a miscommunication.

This paper will first describe the formation of regular yes-no questions and then describe three variational forms and their respective usages:negative yes-no questions,

tag questions, and statement yes-no questions. The paper will then describe how yes-no questions are formed in Japanese. Next, I will discuss some common errors Japanese students tend to make with forming and answering these types of questions in English and what I think is the most important error on which to focus on. Finally, there will be a brief discussion on the implications for teaching yes-no questions to Japanese students of English.

Formation of Yes-No Questions

Quirk et al. (1985, 78) describe the form of a yes-no question by first describing a simple sentence as a subject and a predicate. He further breaks down the predicate into the auxiliary and operator and predication. The operator doesn't always occur in a simple statement but when it does, it is normally the word that "directly follows the subject" (79). Quirk describes the operator in this case as the "first or only auxiliary" and it is key to forming yes-no questions. Quirk breaks this down using the following sentence diagram:

By changing the positions of the subject and the auxiliary / operator, a yes-no question can be formed. When there is only a main verb (also referred to as full or lexical verbs) in the independent clause, it must make use of the dummy auxiliary 'do' to form a yes-no question. Quirk et al. (1985, 80) call this dummy auxiliary the DO-paraphrasis or DO-support. The dummy auxiliary 'do' must also agree with person, number, and the tense of

the declarative statement. In terms of prosody, a yes-no question has rising intonation at

the end of the sentence.

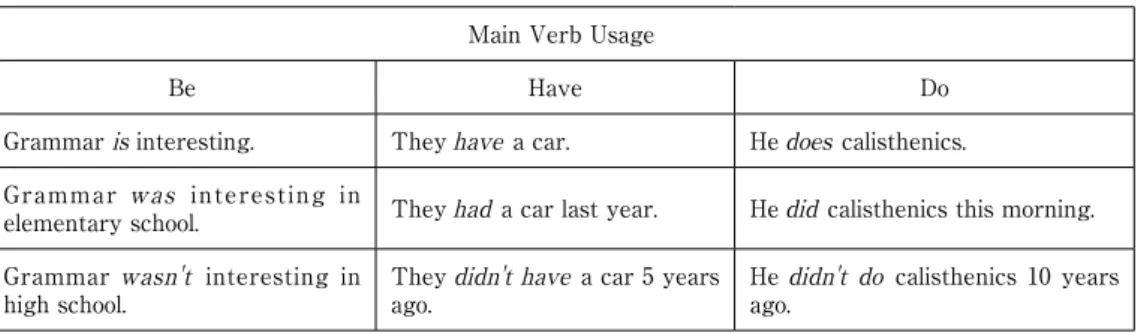

Auxiliary verbs fall into two main categories known as primary verbs and modals. Primary verbs can function as main verbs or as auxiliary verbs (Crystal 1995, 212). Table 1 - Examples of Primary Auxiliary Verbs Used as Main Verbs

Main Verb Usage

Be Have Do

Grammar is interesting. They have a car. He does calisthenics. Grammar was interesting in

elementary school. They had a car last year. He did calisthenics this morning. Grammar wasn't interesting in

high school. They ago. didn't have a car 5 years He ago.didn'tdo calisthenics 10 years

These primary auxiliary verbs show characteristics of being main verbs (212). They can show person, number and tense. Unlike main verbs, the 'be' verb can also take a negative form, or come before 'not', like auxiliary verbs, except in the case of negative imperatives such as, "Don't be absurd!" (Leech & Svartvik 1994, 240-43), but have and do, similar to full or lexical verbs, must make use of DO-support in the form of the dummy auxiliary 'do' to form a negative declarative sentence and yes-no questions, as well as show tense and agreement with the subject. (Quirk et al. 1985, 80). In the yes-no question the verb following the auxiliary-inversion takes the infinitive form.

The 'be' verb as a main verb can continue to act "as an operator even when it constitutes the whole verb phrase" (Quirk, 1985, 81) and therefore does not require the dummy auxiliary verb do.

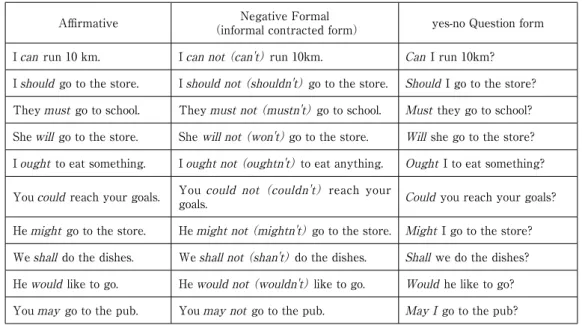

Modal auxiliary verbs can only function as auxiliary verbs to express meanings "which are much less definable, focused, and independent than lexical verbs" (Crystal 1995, 212). Crystal lists 9 modal verbs which are can, could, may, might, will, would, shall, should, and must. He suggests that the verbs dare, need, ought to, and used to have a similar function as modals but are not true modals (Crystal 1995, 212). Leech and Svartvik (1994, 243) however, include dare, need, ought to, and used to as modals, while Swan (2005, 325-326) only adds ought to Crystal's nine. For the purposes of yes-no questions, however, Swan's ten can all be used without the dummy auxiliary do, while dare, need and used to would require the dummy auxiliary verb do.

Table 2 - Examples of Declarative Affirmative and Negative Sentences with Modal Auxiliary Verbs and Their Yes-No Question Forms

Affirmative (informal contracted form) Negative Formal yes-no Question form

I can run 10 km. I can not (can't) run 10km. Can I run 10km? I should go to the store. I should not (shouldn't) go to the store. Should I go to the store? They must go to school. They must not (mustn't) go to school. Must they go to school? She will go to the store. She will not (won't) go to the store. Will she go to the store? I ought toeat something. I ought not (oughtn't) to eat anything. Ought I to eat something?

You could reach your goals. You goals.could not (couldn't) reach your Could you reach your goals?

He might go to the store. He might not (mightn't) go to the store. Might I go to the store? We shall do the dishes. We shall not (shan't) do the dishes. Shall we do the dishes? He would like to go. He would not (wouldn't) like to go. Would he like to go? You may go to the pub. You may not go to the pub. May I go to the pub?

According to Crystal (1995, 212), modal auxiliary verbs distinguish themselves from primary verbs in that modal auxiliary verbs do not have third person 's', and that they do not have nonfinite forms. For example, while primary verbs like have can form "to have, having and had", a modal verb like may, cannot. The modals can, will, shall, may and must sometimes have past tense forms of could, would, should, might, and had to, respectively, while should, ought, could, might, and would do not.

To summarize, a yes-no question can be formed by placing the operator, be it a primary verb auxiliary or a modal verb auxiliary, before the subject. The primary auxiliary verbs should agree with the subject, number, and show the tense. Modal auxiliary verbs do not have a third person singular form 's' but can sometimes show tense. The verb following after auxiliary-inversion should take the infinitive form.

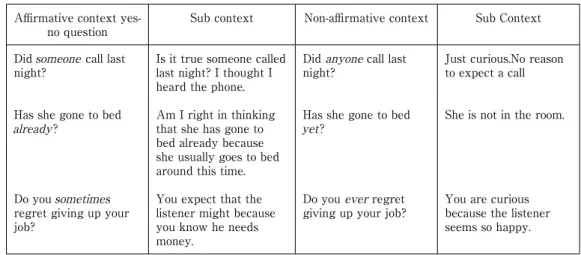

In terms of usage, Huddleston and Pullum (2002) describe characteristic yes-no questions as closed interrogatives, specifically, polar questions, which means the answer should be either positive or negative. They also suggest that characteristic closed interrogative clauses are neutral, meaning there is no particular bias toward a positive or a negative answer. Huddleston and Pullman (2002, 822) use the term non-affirmative

contexts to describe forms that have a neutral effect on yes-no questions. (Quirk (1985,148) refers to these as nonassertive forms.) These terms refer to the any-class words including any, anybody, anywhere, anything, etc. Other examples of non-affirmative contexts include ever, yet, etc. and there are many more. Affirmative contexts (or Quirk's assertive forms) on the other hand, can show a bias toward an expected positive answer on the part of the speaker. Examples of these forms are some, somebody, somewhere, something, already, etc.

Table 3 - Answers to Yes-No Questions with Examples of Affirmative Contexts which Show a Bias for a Positive Answer (Examples Taken from Leech and Svartvik (1994, 126))

Affirmative context

yes-no question Sub context Non-affirmative context Sub Context Did someone call last

night?

Has she gone to bed

already?

Do you sometimes

regret giving up your job?

Is it true someone called last night? I thought I heard the phone. Am I right in thinking that she has gone to bed already because she usually goes to bed around this time. You expect that the listener might because you know he needs money.

Did anyone call last night?

Has she gone to bed

yet?

Do you ever regret giving up your job?

Just curious.No reason to expect a call

She is not in the room.

You are curious because the listener seems so happy.

Variations of Yes-No Questions

This next section will discuss variations of the yes-no questions. The first variation is following the same format as the yes-no questions discussed previously except using a negative with the auxiliary and operator. The operator will use the dummy auxiliary verb do and usually the contracted form of not for when there is no operator with main verbs or the primary auxiliary verbs do and have when they are used as a main verb. The use of the uncontracted form of not following the subject makes the question sound more formal (Huddleston & Pullam 2002, 883; Swan 2005, 345). As stated earlier, the 'be' verb as a main verb does not require the dummy auxiliary verb do (Quirk et al 1985, 81).

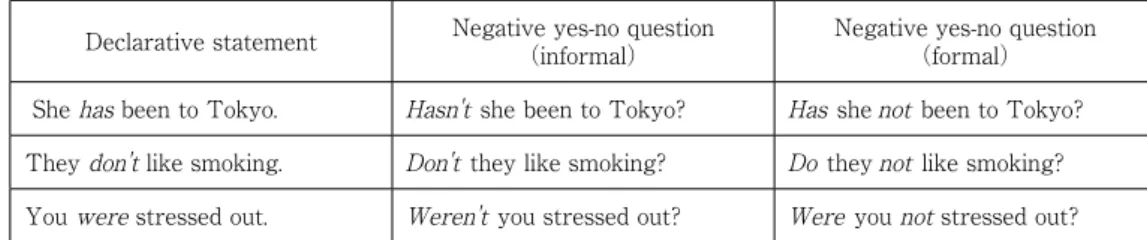

Table 4 - Negative Yes-No Questions with Primary Verbs as Main Verbs

Declarative statement Negative yes-no question (informal) Negative yes-no question (formal)

Grammar is interesting. Isn't grammar interesting? Is grammar not interesting? They had a car. Didn't they have a car? Did they not have a car? He does calisthenics. Doesn't he do calisthenics? Does he not do calisthenics?

As is shown in the table above, the dummy do verb should agree with the number indicated by the subject, and the tense of the main verb in the declarative statement. Table 5 - Negative Yes-No Questions with Primary Verbs as Auxiliary Verbs

Declarative statement Negative yes-no question (informal) Negative yes-no question (formal)

She has been to Tokyo. Hasn't she been to Tokyo? Has she not been to Tokyo? They don't like smoking. Don't they like smoking? Do they not like smoking? You were stressed out. Weren't you stressed out? Were you not stressed out?

In these examples above, we can see that there is a subject-auxiliary inversion with the auxiliary verbs using the contracted form of not with the auxiliary verbs. In more formal language, the uncontracted not comes after the subject. The primary auxiliary verbs show tense and agree with the subject in terms of number. The verb following the auxiliary-inversion takes the infinitive form.

Similar to the primary auxiliary verbs, modal auxiliary verbs follow the same pattern for negative yes-no questions.

Table 6 - Negative Yes-No Questions with Modal Auxiliary Verbs.

Declarative statement Negative yes-no question (informal) Negative yes-no question (formal)

He can run 10 km. Can't he run 10km? Can he not run 10km? You should quit smoking. Shouldn't you quit smoking? Should you not quit smoking? I could have been chosen. Couldn't I have been chosen? Could I not have been chosen?

In the examples above, there is auxiliary-subject inversion with negative contractions formed in informal questions on the modal auxiliary verbs. In more formal constructions, not is uncontracted and comes after the subject. The modals do not change to agree with the subjects, and the main verbs take the infinitive form except in the third example where the main verb phrase begins with the auxiliary verb have, to form the present perfect passive aspect. In that case, have takes the infinitive form and the main verb changes to the past participle form.

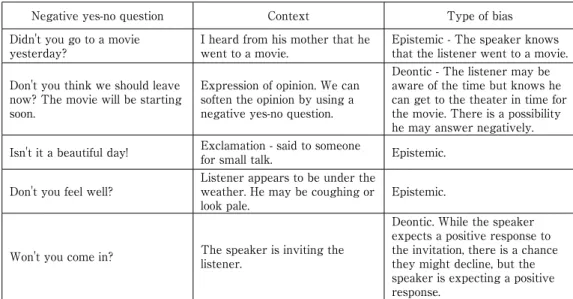

For usage, the negative yes-no question has specific functions. According to Huddleston and Pullum (2002) "questions with negative interrogative form are always strongly biased" although the bias can be either positive or negative depending on the context together with the type of bias and the degree of the bias (880). Huddleston and Pullum describe 3 types of bias:Epistemic bias, where the speaker expects, thinks or knows that the answer is the right one;Deontic bias, where the speaker thinks an answer ought to be the right one;and Desiderative bias, where the speaker wants one answer to be the right one (880). In the previous section on proto-typical yes-no questions, it was shown that non-affirmative context words such as any, anything, yet, etc. are neutral. In negative yes-no questions, however, they become negatively biased. Here are some examples of biased negative yes-no questions from Swan (2005, 345) Leech and Svartvik (2002, 128).

Table 7 - Examples of Positive Bias in Negative Yes-No Questions

Negative yes-no question Context Type of bias Didn't you go to a movie

yesterday? I heard from his mother that he went to a movie. Epistemic - The speaker knows that the listener went to a movie. Don't you think we should leave

now? The movie will be starting soon.

Expression of opinion. We can soften the opinion by using a negative yes-no question.

Deontic - The listener may be aware of the time but knows he can get to the theater in time for the movie. There is a possibility he may answer negatively. Isn't it a beautiful day! Exclamation - said to someone for small talk. Epistemic.

Don't you feel well? Listener appears to be under the weather. He may be coughing or

look pale. Epistemic.

Won't you come in? The speaker is inviting the listener.

Deontic. While the speaker expects a positive response to the invitation, there is a chance they might decline, but the speaker is expecting a positive response.

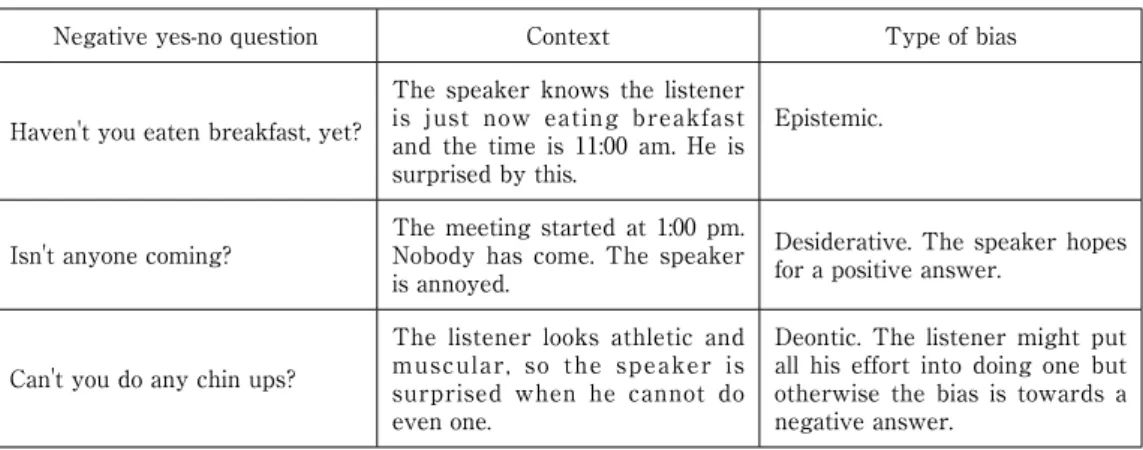

In negative yes-no questions with a negative bias, especially with non-affirmative context words, the speaker may be feeling surprise or annoyance (Leech and Svartvik 2002, 128).

Table 8 - Examples of Negative Bias in Negative Yes-No Questions

Negative yes-no question Context Type of bias

Haven't you eaten breakfast, yet?

The speaker knows the listener is just now eating breakfast and the time is 11:00 am. He is surprised by this.

Epistemic.

Isn't anyone coming? The meeting started at 1:00 pm. Nobody has come. The speaker is annoyed.

Desiderative. The speaker hopes for a positive answer.

Can't you do any chin ups?

The listener looks athletic and muscular, so the speaker is surprised when he cannot do even one.

Deontic. The listener might put all his effort into doing one but otherwise the bias is towards a negative answer.

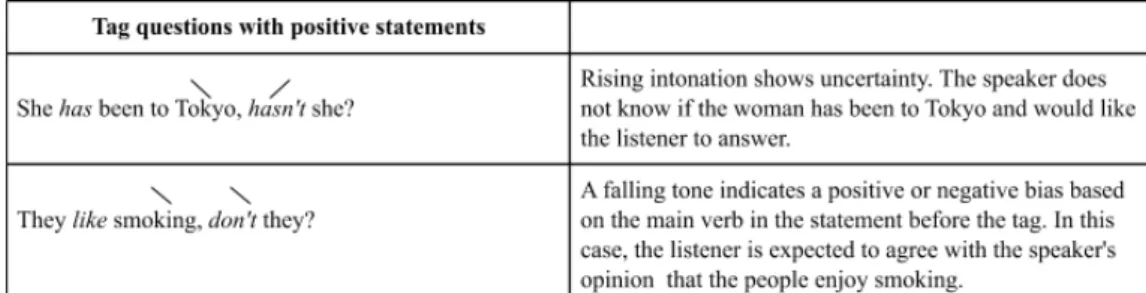

The next variation is a tag question. Tag questions are declarative statements with a yes-no question "tagged" onto the end. In their most basic form, they are made by adding a negative question tag to a positive auxiliary verb operator or a positive question tag to a negative auxiliary verb operator. Huddleston and Pullum (2002, 892) refer to this as reversed polarity. The operator is referred to as a positive or negative anchor by Huddleston and Pullum (2002, 893). The subject in the anchor becomes a personal pronoun for the subject in the tag (893).

Table 9 - Proto-Typical Tag Questions

Positive anchor, negative tag Negative anchor, positive tag Jane has been to Tokyo, hasn't she? Jane hasn't been to Tokyo, has she? The Smiths like smoking, don't they? The Smiths don'tlike smoking, do they? You are stressed out, aren't you? You aren't stressed out, are you?

Depending on the prosody or intonation on the tag, a tag question can be a statement or a question, or "asking for confirmation of the truth of a statement" (Leech

and Svartvik 1994, 127).

Table 10 - Tag Questions and Intonation

The final variation I would like to address is the simplest form of yes-no question - making a declarative statement with rising intonation. Huddleston would argue that while semantically it is a question, it is not a true interrogative clause because it just uses intonation to indicate in speech that it is a question (Huddleston and Pullum 2002, 882). In writing it would have a question-mark to show that it is indeed a question :

/ You can use chopsticks?

This can also be formed as a negative declarative statement. Again, rising intonation is used to show that it is a question.

/ You can't use chopsticks?

In usage, both positive and negative declarative yes-no questions strengthen the answer bias of the statement. "Positive declarative questions have an epistemic bias towards a positive answer, negative ones towards a negative one" (Huddleston and Pullum (2002, 881). They are also used in more casual situations.

Japanese Yes-No Question Form

The Japanese language has yes-no question forms analogous to English yes-no questions and their variations. The basic yes-no question is formed by taking a declarative

statement and adding the particle(か) ka to the end of the statement. The question mark is not necessary if the particle(か) is used. Prosody is similar to English in that the intonation rises at the end of the interrogative statement.

Table 11 - Basic Yes-No Question Using the Particle Question Marker (か)

Japanese often leave out the particle(か)to ask more casual yes-no questions using a rising tone to indicate uncertainty. A question-mark will be used in writing to indicate a question. The particle(か)as final particle suggests that the listener has information that I do not (Cipris and Hamano 2002, p.25).

Table 12 - Yes-No Question without the Particle Question Marker (か)

Japanese have a concept of tag questions, but they are formed much more simply than in English. They are formed by adding the tagね (ne) or ですね (desu, ne) to the anchor clause. There is no reversed polarity. Japanese tend to use this form when both the speaker and the listener have the same information and are looking for acknowledgement (Cipris and Hamano 2002, p.26). Prosody is similar to English in that the speaker’s intonation falls if the speaker is certain. However, it differs from English in that it is uncommon for the intonation to rise when the speaker is uncertain when using the ね (ne) particle. In the case of uncertainty, か (ka) will be used (25).

Table 13 - Tag Questions

Common Errors by Japanese Students

Japanese students of English tend to make a lot of errors with subject-verb agreement and verb tense in writing English (Barker 2008, Izzo 1999;Thompson 2001).These errors are also reflected in their speaking. Yes-no questions are an important skill for students to communicate effectively in English and by and large, when students are speaking, most of these errors are not as obvious. Students are generally proficient at forming proto-typical yes-no questions with a few issues concerning subject-verb agreement and verb tense agreement, especially concerning the dummy do auxiliary (Thompson 2001, 310). The easiest yes-no question form is the positive declarative statement with rising intonation, as this is very similar to how they form yes-no questions in Japanese, as shown above. The students often have a lot of trouble with making and using tag questions with correct subject verb agreement, correct pronoun selection for the question tag, and the use of the dummy do auxiliary (Thompson 2001, 300-306). Negative words that look positive such as few and hardly in tag questions like, "Few of them liked it, did they?" or "It's hardly fair, is it?" also cause problems for even many high level students, but are not really an impediment to communication. Students generally understand the idea of reversed-polarity even though it doesn’t occur in their form of tag questions, and also how the prosody of the tag question can be used to make a question or seek confirmation of an opinion. The mistakes concerning the form of the yes-no question can be corrected, practiced and eventually overcome, or at least the student becomes more proficient and confident in their use.

More challenging for the students are the negative variations of the yes-no statement and adding the particle(か) ka to the end of the statement. The question

mark is not necessary if the particle(か) is used. Prosody is similar to English in that the intonation rises at the end of the interrogative statement.

Table 11 - Basic Yes-No Question Using the Particle Question Marker (か)

Japanese often leave out the particle(か)to ask more casual yes-no questions using a rising tone to indicate uncertainty. A question-mark will be used in writing to indicate a question. The particle(か)as final particle suggests that the listener has information that I do not (Cipris and Hamano 2002, p.25).

Table 12 - Yes-No Question without the Particle Question Marker (か)

Japanese have a concept of tag questions, but they are formed much more simply than in English. They are formed by adding the tagね (ne) or ですね (desu, ne) to the anchor clause. There is no reversed polarity. Japanese tend to use this form when both the speaker and the listener have the same information and are looking for acknowledgement (Cipris and Hamano 2002, p.26). Prosody is similar to English in that the speaker’s intonation falls if the speaker is certain. However, it differs from English in that it is uncommon for the intonation to rise when the speaker is uncertain when using the ね (ne) particle. In the case of uncertainty, か (ka) will be used (25).

question. In Japanese, answering yes-no questions is done in a fundamentally different way to English. In positive yes-no questions, there generally is no issue with answering correctly with correct intent. With negative yes-no questions, negative declarative statement questions and negative-anchor, positive-tag questions, Japanese will base their answer on the negative form of the question, while English speakers will base their answers on the underlying meaning of the question (Leech and Svartvik 1994, 128; Cypris & Hamano 2002, 19-23) which, if a speaker is not familiar with Japanese, will result in a communication breakdown.

Examples (these examples are not transcripts of recorded speech, but amalgamations of common experiences of the author):

Case 1 – Affirmative Yes-no Question

Advisor:Have you finished your paper, yet ? [The advisor is casually enquiring] Japanese Student:Yes.(I have finished)[The student has completed the assignment] Native English Speaking Student:Yes. [The student has completed the assignment] Case 2 – Negative yes-no question

Advisor:(Worried that he hasn't received his student's paper)Haven't you finished your paper, yet ?

Japanese Student:No.(I have finished)[Responding to the negative haven't with "no". - the student had completed the assignment, but the Advisor thinks she has not completed it.]

Native English Speaking Student:Yes.[I have completed the assignment.] If the Japanese student replied with an affirmative:

Japanese Student:Yes.(You are correct. I have not finished the assignment.)[However, the Advisor thinks that the assignment has been completed.]

Case 3:Negative-anchor tag question

Japanese student:Is there a test today? I didn't know.

Canadian teacher:Yes. It's an open book test.(Noticing the student doesn't have a textbook)You didn't bring your textbook, did you?

Japanese student:Yes.(Meaning, you are correct. I didn't bring my textbook.) Canadian teacher(not his first rodeo):Did you bring your textbook ?

Japanese student:No.(Kind Canadian teacher lends his book to the student) Case 4:Negative statement with rising intonation

Canadian husband:(Sees wife starting the laundry)So, we aren't going to Fred and Mary's house for dinner ?

Japanese wife:Yes.(You are correct. We are not going to their house. Mary is sick.) Candian husband:(Still confused)Well then why are you doing laundry now ? Implications for teaching

In teaching yes-no questions and their variations, it is important to build up step by step from declarative statements, to declarative statement questions with rising intonation. As this question form is similar to Japanese, the focus should be on correct subject verb agreement in English. Especially, making sure that students understand and can form the different tenses and of the primary auxiliary verbs be, have and do. Modals should then be introduced and how they are used in a sentence and how they can add so much nuance to sentences. The next stage would be making yes-no questions with auxiliary-inversion and lots of practice with how to use the dummy auxiliary do for yes-no questions that do not have an auxiliary. Students should also have extensive listening practice with video first, followed by audio only to recognize and practice making quick responses. Role plays and other forms of communicative practice should be used so that students can get practice actually using the language in more realistic exchanges (Cowan 2008, 103-107).

Conclusion

Yes-no questions are an important and useful feature of grammar that students need to be able to form quickly and accurately. Japanese students can learn the most basic form of using rising intonation with declarative statements relatively quickly but may make some errors with subject and verb agreement. But these types of errors

would not cause breakdowns in communication. Students need to be explicitly shown the way negative yes-no questions are expected to be answered in English, especially in interactions with native English speakers who do not have experience with Japanese.

References:

Barker, D. (2008) An A-Z of Common English Errors for Japanese Learners. Japan:BTB Press. Comrie, B. (1990) The world's major languages. New York:Oxford University Press.

Cowan, R. (2008) The Teacher's Grammar of English - A Course Book and Reference Guide.

Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

Crystal, D. (1995) English Grammar. In D. Crystal (1995) The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language, pp. 191-233. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

Cypris, Z. & S. Hamano (2002) Making Sense of Japanese Grammar. Honolulu:University of Hawai'i Press.

Huddleston, R. & G. K. Pullam (2002) The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781316423530

Izzo, J. (1999) English Writing Errors of Japanese Students as Reported by University Professors, pp. 1-8. Center for Language Research 1999 Annual Review. Aizuwakamatsu, Japan:University of Aizu.

Leech, Geoffrey & J. Svartvik (1994) A communicative grammar of English, 2nd Edition. Essex: Pearson Education.

Quirk, R., et al. (1985) A comprehensive grammar of the English language. London:Longman. Shibatani, M. (1990) Japanese. In B. Comrie (Ed.) The world's major languages, pp. 741-764. New

York:Oxford University Press.

Swan, M. (2005) Practical English Usage, 3rd Ed. Oxford:Oxford University Press. Swan, M. & B. Smith (2001) Learner English. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

Thompson, I. (2001) Japanese Speakers. In M. Swan & B. Smith (Eds.), Learner English, pp.296-309. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.