The Transnational Growth of Philippine Ethnic Businesses in

the Age of Global Mobility: A Case of Korean-Run English

Language Schools in Baguio, a Regional Capital, the Philippines

Nobutaka Suzuki

*This paper examines the origin and transnational growth of Korean-run English language education businesses, through which Philippine English has been commercialized as a commodity in overseas markets. The Philippines has become one of the most popular destinations for Korean and Japanese students to study English. Two major factors make this decision valid: English competency has become an essential skill for employability and career growth; and studying in the Philippines is more affordable than doing so in native English-speaking countries. Accordingly, English language schools for foreigners in the Philippines have proliferated tremendously. However, little is known about why these English language schools, owned and managed by Korean and Japanese migrant entrepreneurs and investors, have dominated the English language industry in the Philippines. Unlike Korean migrants’ small and self-employed businesses in the Philippines, such as Korean restaurants, beauty parlors, bakeries, and butchers, the schools are both groundbreaking and innovative. These businesses, initially established for early study abroad opportunities for Korean children, have continued to grow rapidly by finding a new overseas market in Japan. Such a transnational spread of these ethnic businesses has been possible not only thanks to their innovative English language training programs, but also because of the de-regulation policy related to visa application by the Philippine authorities, which facilitates this ethnic entrepreneurship. In this paper, focusing on Baguio, a regional capital in northern Luzon, we analyze how Korean migrant entrepreneurs started their English language schools and how they came to develop their innovative educational programs. Further, we shed light on how Philippine authorities have assisted with the growth of Korean ethnic businesses by advertising the study of Philippine English as a new tourist attraction.

Keywords: Baguio, de-Koreanization, education tourism, English language school, ethnic business, Korean migrant, Philippine English, transnational growth

* Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Tsukuba

1. Introduction

English has long been used as a lingua franca in the Philippines, alongside the native Filipino language (Bolton, 2008; Kirkpatrick, 2012; Tinio, 2013). In 1898, when the United States colonized the country, a new public educational system, patterned after American educational institutions, was introduced. It was through these schools that English became a medium of public instruction (Bernardo, 2004; Lorente, 2013). Ever since, English has played a vital role in the country’s social life. Today, the Philippines is known as a migrant-exporting country (Lorente, 2018; Rodriguez, 2010; Tyner, 2009). The transnational development of Filipino overseas workers is rooted in their high English competency. Filipino engineers and nurses working in the global labor market are good examples of educated Filipino professionals and specialists (Choo, 2003; Massenlink and Lee, 2013; Yeates, 2010). At the same time, the present-day Philippines has attracted much attention as a stronghold in Asian regions in the foreign capital-run business processing outsourcing (BPO) industry, such as call centers (Errighi et al., 2016; Forey and Lockwood, 2006; JETRO Manila Center, 2006; Lockwood et al., 2008; Tupas and Salonga, 2016).

In this environment, learning English in the Philippines has become a new option for Korean and Japanese students (Choe, 2016; Hoshino, 2013; Kobari, 2018b; Kobayashi, 2017; Nakagawa, 2015, 2016; Ota, 2011). Especially for those wishing to improve their employability and career growth, the Philippines has become a popular destination, on account of its affordability and geographical proximity. Still, for non-English speaking countries like Korea and Japan, there has long existed a strong belief that English should be taught by native English speakers. Nevertheless, much has been discussed in academic literature about World Englishes and Asian Englishes, both of which are common varieties of English used in multi-lingual situations around the world (Bamgbose, 2001; Kachru, 2005; Murata and Jenkins, 2009). Along this line, a new teaching style is being used by Filipino teachers who learned English as a second language, not as a mother tongue, to teach Philippine English to non-native English speakers, and it has become a new business platform (Hoshino, 2013; Ota, 2011).

English language schools designed for foreigners (hereafter, English language schools) have been established in major regional capital cities such as Cebu, Baguio, and Davao, as well as Manila, the country’s capital city.1 Interestingly, a majority of these schools are owned and

run by Korean and Japanese migrants and investors. Of those schools currently in operation,

1 In this paper, “English language schools in the Philippines” refer to schools exclusively for

international students. This definition excludes the many local English language schools for Filipinos that may be in operation.

CNN, in Manila, established in 1997, and CPILS, operating in Cebu since 2001, are the earliest business enterprises in major cities. The motive behind the birth of the English language school as an ethnic business lies in the growing demand for English competency in Korea. Korean entrepreneurs have tried to make Filipino English competency into a commodity for the commercial market (Heller, 2003, 2010; Tan and Ruddy, 2008; Tupas, 2008b). In the academic field of linguistics and pedagogy, much has been argued about Philippine English as a form of World English and in the bilingual policy of the Philippine education system (Gonzales, 1981, 2017; Kawahara, 2002; Martin, 2008; Toh and Floresca-Cawagas, 2003; Tollefson, 1991; Tupas, 2004, 2008a). Meanwhile, sociology studies dealing with English language schools as ethnic business in the Philippines have been non-existent, apart from Kobari (2018a, 2018b). Kobari, shedding light on the commodification of Philippine English, has shared a common awareness of the issues with the author of this paper (Kobari, 2018b). However, his analysis, only covering its linguistic aspects, has failed to look into the historical growth of English language schools as ethnic businesses.

In the case of Japanese-run English language schools as latecomers in this industry, for example, the Chief Director of QQ English, Raiko Fujioka, reports that he once studied English at the Korean-run CPILS in Cebu city.2 He then attempted to succeed with an innovative Korean

education system based on his own English learning method before eventually developing his own schools. For this reason, for us to understand the origin and development of English language schools as ethnic businesses, Korean-run schools are an ideal focus for academic inquiry.

Along this line, this paper analyzes how Korean language schools as ethnic businesses, have grown in 2 major ways, namely due to Korean migrants’ adaptation to their host country (human and social capital) as well as external factors, such as the policy of the Philippine government as a host country (opportunity structure). In addition, for ethnic businesses to get started and then grow, capital migrants possess will play a vital role. However, the case of the Korean-run English language schools cannot be fully explained in this light. This is because these language businesses have largely depended on the Philippine government’s deregulatory policy, which aims to encompass Korean ethnic businesses among the Philippines’ tourist attractions. In 2004, the Department of Tourism of the Philippines, locating English learners from abroad who were participating in “ESL programs,” undertook deregulatory measures such as the streamlining of visa application procedures to promote Philippine economic development in tandem with other government offices such as the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA), Bureau of Immigration

(BI), and the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA) (The Korean Times, 2009a). Without institutional support from the host country, the success of Korean migrant ethnic businesses would not have been possible.

The primary data and information on which this paper relies was made available through field studies, which were carried out 6 times in Baguio and Cebu between 2015 and 2019. The length of each visit varied from 1 week to 10 days. In addition to school and/or campus visits to Korean- and Japanese-run English language schools, 8 owners of Korean-run schools were interviewed, as were Korean staff members and Japanese managers in the schools’ marketing and student affairs departments, respectively, during stays in Baguio. Further, to obtain first-hand information of how schools have been operated, the author carried out participatory observations for a duration of 5 school days twice, in 2018 and 2019. Through this research, detailed information was made available, including a view of students’ campus life, such as their arrival orientation, English placement test, food service, dormitory life, and one-on-one English lessons. At the same time, to grasp the depth of the Philippines’ Tourism Department’s policy with regard to ESL programs, the author interviewed a Head of English as Second Language Market Development Group (in Manila), the Section Chief of the Department of Tourism (Tokyo Office in Japan) in the Philippine Embassy, and the President of the Association for English Studies in the Philippines (PSAA). The author also visited the Philippine Study Abroad convention 3 times in Tokyo, at events sponsored by the Department of Tourism of the Philippines. This made it possible to learn more about the vital role played by school agents in marketing and promotions. Lastly, the author considers daily Philippines newspaper articles to be vital sources for updates related to ESL programs, Philippine immigration policies, and Korean-run English language schools, as such local events are largely reported in daily newspapers.

2. Research Framework

Ethnic and/or migration studies have long considered distinctive features of migrant ethnic businesses in a host country to be small in size, sole proprietorships, and regarding their fellow countrymen as their primary customers (Higuchi, 2007, 2010; Higuchi and Takahashi, 1998; Sanders and Ness , 1996; Portes and Rumbaut, 2001; Portes and Zhou, 1996). Korean economic activities in Baguio have been no exception. Many scholars have generally analyzed the structural, organizational, and geographical characteristics of ethnic businesses (Sakurai, 2003; Higuchi, 2012; Higuchi et al., 2007). In concrete terms, they have generally been concerned with their process of adapting to the host country, aiming to examine what made migrants choose self-employment and how they found a niche for business. Unlike educated Filipino migrants

working abroad as professionals, ordinary Korean migrants and retirees have limited skills and language competency. They can scarcely find a position in the competitive job market. This outcome is partly validated by their segregation and/or exclusion from their host countries (Hurh and Kim, 1984; Kim and Hurh, 1985; Kwak, 2013; Kwak and Hiebert, 2010; Noh et al., 2012).

Despite the situation described above, understanding the growth of Korean-run English language businesses in the Philippines requires a different perspective. Since their inception, the schools have depended on Korean English learners from their mother country. The success of these businesses was essentially attributed to an overseas niche market. The transnational development of Pakistanis’ second-hand automobile businesses in Japan and the Korean wig industry in Los Angeles are good examples of similar transnational dynamics that shape migrant ethnic businesses (Chin et al., 1996 ; Fukuda, 2012; Nagano, 2010; Portes et al., 2002).

Meanwhile, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has raised an important issue related to migrant ethnic businesses: the economic impact of these ethnic businesses on their host country (OECD, 2010). The OECD pays particular attention to the relationship between the possibility of a new business created by migrant entrepreneurs and their economic contributions, such as employment in a host country. This concern represents a drastic shift of attention, as European countries have faced a serious labor shortage and come to see migrants and their economic activities as empowering to business innovation and job creation. The way in which the OECD explicitly problematizes the potential of ethnic migrant business indicates the degree to which they wish to take advantage of these businesses’ competitiveness toward continued growth. An excellent study on an economic history dealing with the pinball (pachinko) industry, which was originated by Korean migrants in Japan, has demonstrated how Koreans have struggled to grow their businesses into giant service companies (Han, 2018).

In actuality, academic inquiries and discussions about the ethnic entrepreneurship of migrants in a host country/society began in the early 1970s, especially in the area of sociology studies (Boancich, 1973). Viewed from this perspective, the OECD’s awareness of such issues is not truly new. Considering the size, capitalization, and primary customers of ethnic migrant businesses, the economic impact of ethnic businesses on a host country has been extremely limited. By contrast, it has also been reported that some businesses established with sufficient human capital (e.g. education, language proficiency, and economic capital), though small in scale, have developed into full-fledged, transnational migrant industries through the close networking of kinsmen and people from a shared hometown (Fukuda, 2012, 2015; Minamikawa , 2002). This paper, by focusing on Korean-run English language schools, may offer us one of the best case studies in Asia for validating the OECD’s awareness of these issues, namely the possibility of new business innovations among ethnic business enterprises and their impact on the host country.

Located in such a context, the significance of this paper concerns first that Korean entrepreneurs have succeeded in commodifying knowledge of English competency in our globalized world (Heller, 2003, 2010; Tan and Ruddy, 2008). At present, there has been a major shift in economic activities, from the production and consumption of material things to intellectual property such as knowledge, information, and technology (Asia Development Bank, 2007; Burton-Jones, 1999; OECD, 1996a, 1996b; The World Bank, 2002). As the roles played by knowledge continue to be more influential than ever, our economic success will depend largely on how we use our knowledge practically. In other words, through the commodification of English competency by Korean ethnic entrepreneurs’ innovation, both the job creation realized for Filipino English teachers and the growth of other related economic activities, such as real estate businesses, food and restaurant companies, and laundries, can become a reality. This is exactly what the OECD means by “new business creation,” namely the innovative commodification of Philippine English.

In this light, a study on the Korean education industry run by Korean migrants in Canada offers us excellent insight (Kwak, 2013; Kwak and Hiebert, 2010). According to this study, since 1994, when a visa exemption agreement was concluded between Korea and Canada, Korean ethnic business entrepreneurship has become marked. One of the areas in which this can be seen is the growth of ESL school business and study abroad industry agents. The establishment of such businesses in Canada can be largely attributed to the underestimation of their academic credentials in Canada and their English incompetency. Due to their segregation from the competitive job market in Canada, Korean migrants could not help but create niche businesses to ensure their livelihood. However, in the case of the English language industry in the Philippines, Korean businesses relied only on customers from their own home country, not those from the Philippines, from the very beginning. Korean business cannot be explained in terms of the framework of segregation from the dominant majority, as their success depends entirely on how English learners in Korea can be recruited, whether their businesses succeed or not, among ethnic minorities. Consequently, Korean ethnic businesses running English language schools for foreigners have dominated the English language industry in the Philippines.

3. The Korean Diaspora in the Philippines

As of 2018, Koreans in the Philippines constitute the county’s largest foreign community. Bilateral relations between the Philippines and Korea were once very close (Kim, 2016; Kutsumi, 2007; Lee, 2006a, 2006b). These addressed tourism, business, education, retirement life, and missionary activities. Since 2006, Korean visitors to the Philippines have outnumbered American

visitors, making them the group most likely to visit. Comparing the numbers of foreign travelers visiting the Philippines in 2006 and 2017, we can see that the number of Americans rose from 560,000 to 950,000, a 68% increase; Japanese tourist numbers rose from 420,000 to 580,000, a 38% increase; and the number of Koreans rose from 570,000 to 1.6 million, an increase of 281% (UP-CIFAL, 2018). Consequently, by 2017, Koreans comprised one-fourth of all foreign visitors. Unsurprisingly, the number of Korean migrants in the Philippines, that is, all Koreans entering the country with an appropriate permit and/or visa, has also grown. In 2009, there were 110,000 in the country (Table 1), and in 2019, their number is estimated to be between 80,000 and 90,000.

The formation and expansion of the Korean community in the Philippines has had a great influence on Philippine society as a whole (ABC-CBN News, 2008; Gomez, 2011; Kim, 2016). This influence, known as “Koreanization” or the “Korean wave,” has been well received. In particular, Korean consumer culture such as K-Pop (Korean popular music), Korean drama and film, Korean cosmetics, and Korean foods are favored by young Filipinos and represent Korean cultural distinction (Igno and Cenidoza, 2016; The Korean Times, 2009a, 2009b; Philippine Daily Inquirer, 2011b). Korean communities in the Philippines, in addition to the Metro Manila area, have spread to cities including Baguio, Clark, Cebu, Dumaguete, Bacolod, and Davao (Kutsumi, 2007). In these places, Korean protestant churches, Korean business associations, and Korean restaurants with billboards written in Hungul lettering all indicate the extent to which Koreans now constitute a significant part of the regional towns (Barros, 2006; Kim, 2016; Kim and Ma, 2011).

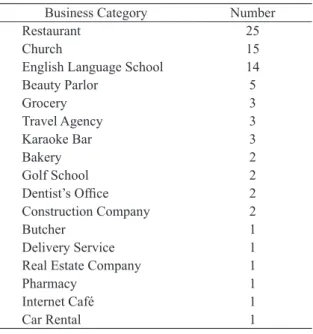

Table 2 indicates the number of Korean business establishments in Baguio, a regional capital of Luzon in the Philippines. It clearly shows what types of ethnic businesses are in operation. The largest share is Korean restaurants, with 25. Churches and English language schools occupy the second- and third-largest types of business, with 15 and 14, respectively. Meanwhile, the “other”

Table 1. Numbers of Koreans Migrants to the Philippines, 2001–2017

Year Number 2001 24,618 2003 37,100 2005 46,000 2007 86,800 2009 115,400 2010 96,632 2012 88,102 2015 89,037 2017 93,071

Source: UP-CIFAL (2018); Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), the Embassy of the Republic of Korea in the Republic of the Philippines (n.d.)

category includes small ethnic business for migrants such as beauty parlors, karaoke bars, and bakeries. Table 3 shows the types of Korean businesses in Baguio, classified by customer type and services offered. It also shows that the majority of these firms are small enterprises and sole proprietorships. Though few businesses handle specifically ethnic services, apart from Korean restaurants, a majority of businesses serve the daily needs of Korean migrants. Among them, the only exception are Korean-run English language schools. As will be explained in later chapters, these schools offer English language training exclusively for foreigners, not for local Korean migrants. Most of the students, who are recruited by school agents from their home countries of Korea and Japan, undertake intensive English language training with Filipino teachers for specific periods while staying in the schools’ dormitories, which also provide meals.

Of these types of businesses, Korean-run English language schools have had a tremendous impact on the Philippines’ economy. Steve Han, President of the Korean Sports Community in Baguio, says that one Korean student spends around 40,000 pesos per month on accommodation, food, and other needs (The Manila Times, 2015). Undoubtedly, their presence is a welcome addition that boosts local economies. Their economic influence permeates all aspects of society, affecting job creation and related service industries like restaurants, laundries, tourist attractions, and real estate.

Despite the expected economic impact on the local Philippine economies, little has been known about how English language schools for foreigners were established in the Philippines.

Table 2. Korean Businesses by Category in Baguio, the Philippines

Business Category Number

Restaurant 25

Church 15

English Language School 14

Beauty Parlor 5 Grocery 3 Travel Agency 3 Karaoke Bar 3 Bakery 2 Golf School 2 Dentist’s Office 2 Construction Company 2 Butcher 1 Delivery Service 1

Real Estate Company 1

Pharmacy 1

Internet Café 1

Car Rental 1

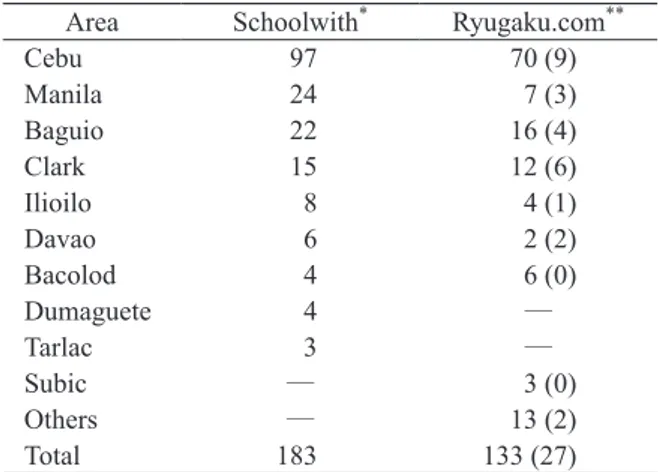

Even the exact number of English language schools is not readily available in the Philippines. As of June 2012, the number of TESDA-accredited private schools offering foreign language courses in the Philippines was 499, but not all of these provided English instruction (JETRO Manila Center, 2012). An alternative way to estimate the number offers us a picture of the English language school industry (Table 4). According to Schoolwith and Ryugaku.com, 2 major study abroad agents in Japan, as of September 2019, the reported numbers of English language schools were 183 and 160, respectively. These may include some schools that are now closed or that have transferred to other sites. Aside from Manila, the capital city, the schools have been concentrated in the regional capitals (Cebu, Baguio, Clark, Iloilo, Davao, and Dumaguete), where Korean communities have been established as well.

Table 3. Typologies of Korean Businesses in Baguio

Types of Services Offered Type of Customer

Korean Other Nationalities Ethnic Services Ethnic Markets: Grocer, Baker, Butcher Ethnic Niche: Korean Restaurant, Café

Non-Ethnic Services

Markets Protected by the Language Barrier: Churches; English Language Schools; Beauty Parlors; Travel Agencies; Karaoke Bars; Golf Schools; Dentist’s Offices; Construction Companies; Delivery Services; Real Estate Companies; Pharmacies; Internet Cafés; Car Rentals

Migrant Business Niche: English Language School

Sources: Adapted from Higuchi (2010), Baguio Times (2015)

Table 4. Distribution of English Language Schools and/or Campuses for Foreigners Provided by Two Major School Agents

Area Schoolwith* Ryugaku.com**

Cebu 97 70 (9) Manila 24 7 (3) Baguio 22 16 (4) Clark 15 12 (6) Ilioilo 8 4 (1) Davao 6 2 (2) Bacolod 4 6 (0) Dumaguete 4 ― Tarlac 3 ― Subic ― 3 (0) Others ― 13 (2) Total 183 133 (27)

* Figures include schools that are now closed.

** Figures in parentheses ( ) refer to schools that are now closed.

Nevertheless, what is common among them is that almost all of the schools offer on-campus student housing and provide students with one-on-one, personalized tutorials. In Cebu, known for its high concentration of Japanese-run English schools, in addition to those run by Koreans, these private tutorials have been the backbone of English language education. In short, the success of English language schools in the Philippines lies in their development of original and unique teaching styles in private lessons to help students develop effective speaking ability.

4. The Korean English Language Schools as Ethnic Businesses

The regional capital city of Baguio, 250 km to the north of Metro Manila, is a popular summer resort in northern Luzon with comfortable and cool weather. Historically established as a summer capital by American colonial planners in the early 20th century, it was, prior to

World War II, home to large American and Japanese migrant communities. Given the many ethnolinguistic groups and diverse cultural traditions of its residents, Baguio has maintained a cosmopolitan outlook, and higher educational institutions such as the Philippine Military Academy, the University of the Philippines at Baguio, and Saint Louis University, founded by Belgian missionaries, have concentrated there (Prill-Brett, 1990; Reed, 1976). These schools attract prospective students and serve as the center of excellence in higher education for northern Luzon. As shown in Table 4, there are currently 22 English schools and/or campuses, some of which have since closed. Not all of them are run by Koreans. Further, there are many other smaller English schools, some of which are exclusively for Koreans and others that are unaccredited by BI and TESDA.

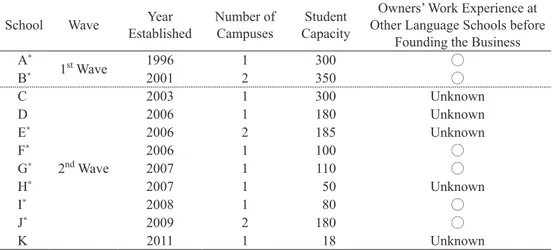

Table 5 is an overview of the city’s major Korean-run English language schools. The Table includes each school’s founding year, number of campuses, student capacity, and the past work experience of the owners at other English language schools. The Table indicates the following: first, Korean owners can be divided into 2 waves (first-wave owners, for Schools A and B, and second-wave owners, for Schools C–K). In the case of first-wave owners, they arrived in the Philippines between the late 1990s and the early 2000s and established the schools. These are now larger in scale. By contrast, second-wave school owners, who came later, often had work experience at another English language school as a manager before opening their own business. The value of this apprenticeship should not be underestimated, because none of 8 school owners (Schools A, B, E, F, G, H, I, and J in Table 5) interviewed as a part of this study had job experience in the education industry or business prior to their visit to the Philippines. Through this exposure to the language school business, they were able to accumulate management skills (Bailey and Waldinger, 1991). Further, the success of the second wave can be partly attributed

to the formation of a fraternal association, Baguio English Schools Association (BESA), in 2005. This organizational linkage enabled both first- and second-wave owners to meet and talk with each other on a regular basis concerning their experiences. Without this institutional support, the second wave would not have succeeded.

Below are 2 brief histories that explain how the first wave owners established their schools. Both owners A and B, who belong to the first wave, are in their mid-40s. Owner A runs the oldest English language school in the Philippines and is considered the pioneer in this business.3

His story, below, deserves special mention because it explains precisely the origin of English language schools in the Philippines. In 1995, when he was a university student, he travelled to Baguio to study English at a private tutorial boarding house run by a Korean missionary. This was the first time he studied Philippine English. He was both overwhelmed by the Filipinos’ command of English and disappointed by the poor quality of his own school’s management, because it lacked a systematic curriculum. The content of the lessons depended largely on the experiences of the Filipino teachers. In response to his feelings of discontent, he decided that he could do much better to improve students’ skills. After graduating from university in 1996, he returned to the Philippines to establish his own English schools. Vowing not to repeat such a mistake for his fellow Koreans, he opened his own school.

His initial customers were Korean children anxious to learn English. Owner A often returned to Korea to recruit children interested in summer and winter English camps. In 1997, a year after

Table 5. Korean-Run English Language Schools in Baguio

School Wave EstablishedYear Number of Campuses CapacityStudent Other Language Schools before Owners’ Work Experience at Founding the Business A* 1st Wave 1996 1 300 ○ B* 2001 2 350 ○ C 2nd Wave 2003 1 300 Unknown D 2006 1 180 Unknown E* 2006 2 185 Unknown F* 2006 1 100 ○ G* 2007 1 110 ○ H* 2007 1 50 Unknown I* 2008 1 80 ○ J* 2009 2 180 ○ K 2011 1 18 Unknown

* Schools for which the authors interviewed the owner in person Source: Author’s field research

founding his school, and following the Asian Financial Crisis, which led to the devaluation of the Korean Won and the worsening of the Korean economy, many students suspended their trips to Baguio (Kwon, 2004). Nevertheless, he worked hard to keep tuition levels stable so as to serve the Korean children. This decision helped him to gain the trust of his customers.

Owner B runs the second-largest English language school in Baguio and was the second to enter the market.4 Five years after owner A opened his first school, owner B travelled to Baguio to

study English for 2 months, arriving at a school run by his friend in 2002. This language school was originally operated in a private boarding house. Soon after, owner B decided to stay on and work as the school’s assistant manager, and in 2006, he took ownership of the business. He recalls that running the school was a real challenge, because he had few students, but he hoped that “someday water in the cup would overflow.” Owner B stresses that, when he first came to Baguio, there were no others working in this space, apart from owner A, so he arranged to meet with owner A to seek practical advice on managing a school.

There are 2 striking points to be noted from owner A’s and owner B’s experiences. They both enrolled in small, personalized tutorial lessons offered at a private boarding house run by Korean missionaries, interacting with those who may be seen as the earliest Korean entrepreneurs entering the English language business, and especially those aimed at serving Korean children. They also essentially followed the same basic format of offering intensive tutorial lessons and were the first ones to undertake the commodification of Philippine English.

In contrast to owners A and B, owners C through K belong to the second wave, and have been the driving force in laying the foundation for successful language businesses, especially since 2006 when “English language fever” overwhelmed Korea (Choi and Kim, 2017; Finch and Kim, 2012; Jones, 2013; Kim, 2015; Kobayashi, 2017; Lee and Koo, 2006; Park, 2009; Park and Abelmann, 2004; Shim and Park, 2008). Unlike the earliest business owners, these owners are much younger, and their schools are smaller in size. Still, what is common among them is that they have some work experience at other English language schools. Among the younger owners, 2 graduated from a university in the Philippines. Born after the mid-1990s, when the push for early study abroad became so prominent in Korea, they had not only already studied abroad for their university degrees, but also had decided to open their own schools as migrant entrepreneurs. The rest in this cohort are similar in that they opened their schools after completing university courses in Korea. They did so because they could start English language school with a small amount of capital. Although owner J worked for 4 years at a Korean company after completing his university studies,5 due to the ongoing economic recession in Korea, he decided to leave to 4 Interview with owner B on 22 August 2017.

explore a new career abroad. After arriving in Baguio, he worked as a manager at a language school. This school, due to poor management, was ultimately unsuccessful; learning that his boss was thinking of closing the school, he bought it in 2009.

As described above, the groups of owners are different in many regards, though they are alike in that their schools began as exclusive venues for Korean children’s summer and winter camps, but gradually shifted to offer general English as a second language (ESL) courses year-round in order to accommodate more students. For example, owner E opened his school in 2006 exclusively for children such as elementary and junior high school students.6 Five years later,

the school began offering the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) and the Test of English for International Communication (TOEIC) preparation courses, as well as other ESL courses. Similarly, owner F, who opened his business with a friend in 2006 offering elementary and/or intermediate courses, decided to offer general ESL instruction in 2008, and added TOEFL and TOEIC courses in 2009.7

To summarize, Korean-run English language schools were developed exclusively for Korean students in order to meet their diverse needs (i.e., in terms of the schools’ operational language, menus, campus life, recreational activities, and dormitory life) for a variety of ages, including children, university students, and adults. In this sense, these businesses can undoubtedly be classified as “ethnic businesses” aiming to fill an ethnic niche. To put it another way, Korean ethnic businesses are based on supply and demand, taking into account the Korean market’s needs and Korean entrepreneurship in Baguio, and to serve Koreans’ best interests. As shown in Table 3, this type of ethnic business resembles other Korean businesses, such as beauty parlors and karaoke bars, in that they are protected by the language barrier and can be started with only a small amount of capital. Nevertheless, the reason this type of ethnic business has developed from being a small business to serve the Korean migrant community to operate on a larger scale and deal with multiple overseas markets and many nationalities lies in the “English fever” that overwhelmed Korean society after 2000 (Kobayashi, 2017).

The high concentration of English language schools founded by owners from the younger group between 2006 and 2008 can be attributed to the growing demand for early English study abroad within Korea (Kobayashi, 2017). Referring once more to Table 1, it is clear that the number of Koreans arriving in the Philippines between 2001 and 2017 grew steadily until the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. Courses for children, unlike those for university students and adults, require a great deal of attention and around-the-clock care for and supervision of the students. These schools also often offer special classes, known as “junior summer (July and

6 Interview with owner E on 23 August 2017. 7 Interview with owner F on 25 August 2017.

August) and winter (January and February) camps.” These camps often include intensive English classes and extracurricular recreational activities. In addition to offering these classes, many owners must take care of almost all responsibilities related to students’ everyday lives. This includes marketing and sales promotions, meals and lodging, transporting students to and from the airport, and maintaining regular contact with their parents by phone. Owner I, recalling the early days of his business, said that taking care of younger students was tiresome and “not a picnic.”8 At the same time, he considered the work to be rewarding: Ii he worked diligently and

unselfishly, the students, upon returning home, helped to promote his school by word of mouth. Further, they often became regular customers, returning year after year.

However, younger students are only some of their regular customers. The owners have introduced a military-like, disciplined style of education, generally called “Sparta.” It confines all students to the school campus and bans them from leaving the campus for the purpose of maximizing the output of the intensive English training provided. It is from Baguio that, later on, this unique style of education came to spread to almost all of the language schools in the Philippines. This rigorous teaching style came into being because it was rightfully predicted as being able to win the hearts of Korean parents who hold the decision-making power in school selection.

Some schools, after accepting a group of Korean university students, have come to enjoy the status of being university-affiliated by signing a memorandum of understanding with local Philippine universities. For example, owner B acquired this status as the English language school affiliated with a university in Baguio; his school has received a number of Korean university students annually during the summer and winter terms by offering meals and a dormitory for the visiting students. Aside from providing the local university’s lectures, the school has also played an intermediary role in bridging Korean and local universities and/or Philippine local communities and Korean students by offering outreach programs. In short, English language schools, in coping with a variety of needs within Korea by age, wave, and purpose, came to develop a highly unique and original educational style and program.

Taken together, we can say that the Korean-run English language schools originated as private tutorial boarding houses run by Korean missionaries, but over time developed a strong disciplinary-focused system offering both innovative and rigorous English lessons. They also represent Korean business entrepreneurship as ethnic minorities. By “innovative,” we mean that for Koreans to be competitive in the business market, the English language schools attempted to create a more attractive and unique educational style to meet the domestic demand in Korea.

The previous literature (Kwat , 2013; Kwak and Hiebert, 2010) has pointed out that even in Canada, where Korean migration and study abroad for English have intensified, Korean migrants have started their own English language businesses. This deserves special mention because, within expatriate Korean migrant communities, there have been other Korean entrepreneurs with similar motives aiming to undertake English language businesses simultaneously. In Baguio, however, the earliest business model of English language schools was originated among Korean missionaries’ private tutorial boarding houses. Meanwhile, in Canada, English language schools for ESL students were founded much earlier by Canadians. In this sense, it can be concluded that Korean-run English language schools in the Philippines should not be viewed as a mere mimic and imitation of schools operating in other countries; rather, they were begun by innovative and groundbreaking entrepreneurs, as ethnic minorities in the Philippines aimed to meet the domestic demands of the Korean middle classes because there were no others already in the business.

5. Market Diversification toward Ethnic Global Businesses

The number of Korean migrants in the Philippines has declined since 2009, immediately following the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. Accordingly, the Korean community in Baguio, whose population once exceeded 10,000, had decreased to just 5,000 as of 2019 (ABS-CBN News, 2008). This sharp decrease was largely due to the devaluation of the Korean Won, which was triggered by the economic depression of 2008. Korean students were the most affected, as they were by and large still financially dependent on their parents. Further, some Korean businesses closed due to the decreasing Korean population. Ever since, the number of Korean migrant businesses in Baguio has failed to increase.9 In these circumstances, even Korean

language schools have struggled following the narrowing of the Korean market.

Despite this, these schools have been able to overcome the predicament of declining populations and student numbers by exploiting a new market opportunity in Japan, especially since 2010. Though the exact number of Japanese students in the Philippines is not available, the Department of Tourism (DOT) says that, since 2010, the number of students wishing to study English has quickly risen from a state of nonexistence (Yokoyama, 2019). Still, we need to be very careful in characterizing this population because such the increasing number of students from Japan has largely been attributed to a new overseas market opportunity in Japan.

One explanation for this increase can be found in the report on “global-minded human resources” prepared and submitted by Japanese business communities and the Japanese

9 Personal communication with Hidenobu Oguni, President of the Japanese Association in Northern

government in 2010 (Global Human Resource Development and Promotion Committee, 2011). This report points out that for Japan to catch up with the fast-growing pace of globalization, the Japanese business community will need more workers with a solid command of English who can work in a multicultural business environment. Based on this assessment, human resources development was identified as a pressing need for Japan’s future success. Some Japanese companies, responding to this demand, began sending their staff for language training in the Philippines, which led to a great deal of media publicity (Sawada, 2014). Aware of these internal changes in Japan after 2010, Korean English language schools have quickly and aggressively worked to exploit this new Japanese market opportunity.

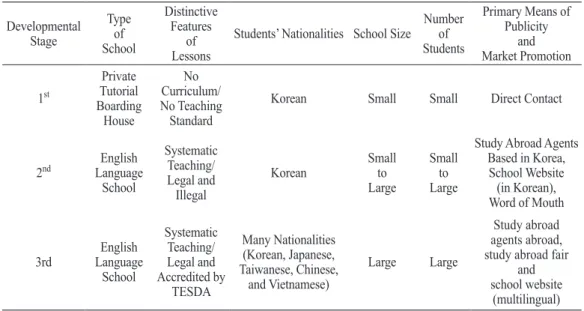

Still, the reason Japanese people have welcomed the new opportunity to learn English in the Philippines cannot be explained by physical proximity and affordability alone. The most striking point for the Japanese market is a highly personalized style of teaching known as the “one-on-one lesson.” This approach has proven effective in the Korean market for the past decade by improving students’ speaking and communication skills. For the Japanese market, these personalized English lessons are a good match. This is not to say that Korean language schools, relying on new and growing market opportunities, have never changed in hopes of attracting more international students. In fact, they were willing to change their school system and standards that were exclusive to Koreans. As Table 6 shows, as long as the schools continued to accommodate Koreans alone, the schools’ facilities, student services, marketing promotions, and information dissemination caused few problems. However, once they started to appeal to the global market, the quality of their facilities, education program, and all of the other services they

Table 6. Developmental Patterns of Three Korean English Language Businesses

Developmental Stage Type of School Distinctive Features of Lessons

Students’ Nationalities School Size Numberof Students Primary Means of Publicity and Market Promotion 1st Private Tutorial Boarding House No Curriculum/ No Teaching Standard

Korean Small Small Direct Contact

2nd Language English School Systematic Teaching/ Legal and Illegal Korean Smallto Large Small to Large

Study Abroad Agents Based in Korea, School Website (in Korean), Word of Mouth 3rd Language English School Systematic Teaching/ Legal and Accredited by TESDA Many Nationalities (Korean, Japanese, Taiwanese, Chinese, and Vietnamese) Large Large Study abroad agents abroad, study abroad fair

and school website

offered became subject to critical evaluations by students.

The schools that once served only Korean dishes when Koreans were their primary students must now cope with the dietary needs and preferences of other nationalities, hire staff members who can speak Japanese to serve as student managers, establish Japanese-language websites to accommodate overseas marketing and publicity, and prepare printed materials in many languages.10 One owner, belonging to the second wave, reported that when he went to Japan on

a marketing trip, he was paid no serious attention because he spoke no Japanese. By contrast, most schools have prepared formats and website contents depending on the nationalities they wish to target. For example, most of the schools often upload testimonials that include detailed “success stories” from many students. These data may be very influential for Korean parents in choosing the best school for their children. Meanwhile, some other schools show the wide range of students’ nationalities in the Japanese market, because they know that many Japanese people have a tendency to avoid schools with high concentrations of Japanese students.

For the reasons outlined above, exploiting new markets was a tough challenge for each school. They knew that, if they dealt poorly with these demands, it would harm their reputation and status. Furthermore, in the Japanese market, the discipline-oriented and military-like education provided by a “Sparta course,” which does not allow students to leave the campus after class, would hardly be acceptable to a majority of adult and/or university students. More comfortable but intensive English training programs were very welcome.

Due to the growing national diversity of these schools, all schools have been forced to “de-Koreanize” themselves by enhancing their cultural diversity. In keeping with this understanding, many schools have created websites and prepared documents for distribution in many languages, including Korean, Japanese, Chinese, and Vietnamese. In doing so, a school owner’s Korean nationality also becomes imperceptible on the school’s website. These attempts represent how drastically the Korean-run English schools have shifted from pursuing the small, Korea-oriented market to becoming more global businesses aimed at the overseas market.

At present, these language schools have proactively attempted to display their de-Koreanized school atmosphere, brought about by market diversification, as a key selling point. The homepage of one school’s website features a picture of students with diverse nationalities from East Asia to the Middle East. The owner of this school considers cultural diversity to be an important selling point in the school’s marketing efforts. By accelerating their de-Koreanization efforts, these Korean language schools intend to create a multicultural atmosphere in which students of different nationalities will be motivated to practice English. This benefit is nothing

10 For example, owner I’s school created a Japanese-language website and opened an office in Japan

less than a product of market diversification, and it shows why the Korean language schools decided to pursue this approach, flexibly adapting to the schools’ changing opportunity structures.

6. Changing Opportunity Structures in the Philippines:

Learning Philippine English as Tourist Attraction

So far, we have discussed how the establishment of Korean-run English language schools succeeded in developing a unique educational style (Sparta and Semi-Sparta) as well as an original approach to language teaching (one-on-one lessons), and how these schools have been able to find a new market opportunity in Japan. However, it should be noted that the transnational growth of the English language school business has been closely related to the domestic opportunity structure in a host country that welcomes foreign students. This is because the Philippine government and other concerned authorities have attempted to promote further Korean investment as a means of developing the Philippine economy, in particular with an eye toward stimulating regional economies through tourism (Board of Investments, 2009; DOT , 2009).11

Especially after 2000, the Philippines’ economic development plan has aimed to boost its economy by attracting foreign investors and international travelers. The “special visa for employment generation,” made available for such investors by a Philippine presidential decree in December 2008, is a good example (GMA NEWS, 2009). This privileged legal status, available as long as a business enterprise and/or investor employs more than 10 regular Filipino workers, provides benefits such as attractive tax incentives. As of April 2010, the visa had been issued to 128 Koreans, almost all of whom were involved with an English language business. At that time, the World Tourism Organization (WTO), a special arm of the United Nations, advocated the vital role of tourism promotion as a solution to alleviating poverty (WTO , 2005). As a result, tourist receipts attracted a great deal of attention in the Philippines. Considering global economic trends, it is no wonder that the Philippine government has chosen to welcome Korean visitors for tourism, employment, studying, and investment purposes, all of which have the potential to boost the economy.12

11 In 2004, the number of international travelers to the Philippines continued to increase, a trend that

continued until the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. According to the Board of Investment of the Philippines, the ratio of foreign receipt accounts among the total GDP increased from 1.9% in 2003 to 3.4% in 2007 (Board of Investments, 2009; Department of Tourism, 2009).

12 There is no data available concerning how Korean English language schools invest their money.

However, according to QQ English, one of the first and largest English language schools in Cebu, owned by Raiko Fujioka, a Japanese Chief Director, Fujioka invested 160 million pesos for the transfer and expansion of his school within Cebu’s IT Park. Cebu City Vice Mayor Joy Augustus Young noted the tremendous economic impact on Cebu, saying that education tourism would boost the city’s economy and create more employment opportunities for Cebuanos (The Philippine Daily Inquirer, 2012a).

As of 2019, there were at least 2 important requirements that foreign students had to meet to study English in the Philippines. One is studying at an official, TESDA-accredited language school. The other, based on the issuance of an acceptance letter by the TESDA-accredited language school, is a BI-granted special student permit for foreigners entering the Philippines on a tourist visa. This legal framework for welcoming foreigners coming for English training was implemented in 2004. Along with this intragovernmental arrangement, the DOT began promoting learning English via an “ESL (English as a Second Language) tour program” as a commodity for the first time and supported the effort by launching a publicity campaign in overseas markets (The Korean Times, 2009a). To this end, Philippine government offices such as the DFA, BI, and TESDA signed a memorandum of understanding aiming at establishing a new framework through which any foreigners holding a tourist visa are eligible to study English as long as their SSP has been secured (DOT , n.d.).

What made the Philippines a popular destination for learning English is that the Philippine government has attempted to locate the ESL tour program in the context of promoting the local tourism industry (DOT , 2011). For the DOT, learning English in the Philippines does not simply refer to studying English at a language school. Rather, it is intended to include a variety of extracurricular activities through which English conversations with local residents is practiced as a lived experience, and visiting to feel, see, and touch the Philippines’ natural resources, local cultures, and heritages (The Seoul Times, n.d.). In short, this is the commodification of Philippine English at an affordable price. The countries chiefly targeted by the Philippine marketers were carefully selected: China, Korea, Taiwan, and Japan were chosen due to their convenient flight access. The DOT has come to refer to this combined experience of learning English and tourism promotion as “education tourism” by distinguishing learning Philippine English from other tourist attractions (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 2012a, 2012b). In addition, the Philippine government regards the Philippines as “a destination in Asia for learning the English” (Nelle, n.d.). Attaching a new meaning to English education within the field of tourism has become possible as a result of the Philippines becoming more aware of the economic effects of the growing demand for Philippine English in the Korean and Japanese markets.

By contrast, the introduction of the ESL tour program by the DOT allowed the Philippine government to intervene in the regulation of students’ registration and school management (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 2011a). The growing awareness of the need to clarify students’ legal status has led to more rigorous quality control among schools. For schools to be accredited by TESDA, they must prepare many documents related to their curriculum, teachers’ qualifications, facilities, and financial statements showing that they meet certain standards. In a sense, TESDA accreditation has contributed to the elimination of inappropriate and poorly managed schools in

the English language-learning business (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 2007).

The strategy the Philippine government employed for raising the standard of English language schools—focusing on combining English education with attracting tourism—has created a sound, reliable, and appropriate market environment in which to keep the English language school business sustainable, and eventually to establish the Philippines as the hub of English studies in Asia. To this end, it has tried rigorously to clarify the status of both students and language schools.13 At the same time, there remained an unresolved issue as the market

became gradually globalized: there is no systematic guideline or framework for ensuring the quality and standard of English language schools. TESDA accreditation does not guarantee the quality of language education (Cebu Daily News, 2015; Philippine Daily Inquirer, 2015a, 2015b). Despite such an issue, the reason Philippine English has remained competitive in overseas markets relates to its affordability, easy access to the Philippines, and changing notions of the use of English (Yoshino, 2014). People from non-English–speaking countries are more concerned about the affordability and accessibility of employability and career growth in a competitive job market.

7. Conclusion

It has been widely understood that ethnic migrants’ businesses can survive in a host country only by either dealing in ethnic products and foods or finding an ethnic niche. Due to limited market opportunities and the small sizes of most migrants’ businesses, no serious attention has been paid to their economic contributions to their host country. This paper, however, demonstrates a somewhat different trajectory of migrant ethnic businesses: that with English competency being commoditized as knowledge for the overseas market, Korean-run English language schools have greatly contributed to boosting the Philippines’ local economy by creating job opportunities and activating service industries such as restaurants, laundries, tourist attractions, and real estate businesses. The evolution and continued success of the Korean language school business in Baguio represents a complex relationship related to ethnic businesses in the contemporary globalized world, one that cannot be explained by the segregation and/or exclusion of ethnic minorities/migrants from the host country.

Korean English language schools, which once faced a critical economic recession that led to the narrowing of the Korean market, became motivated to look for a new overseas market like Japan. Behind this transnational growth there are 2 advantages: the original and unique style

13 To this end, the DOT helped organize the Association for English Studies in the Philippines in Japan

of language teaching developed by the schools and their affordability. In particular, one-on-one lessons, which have proven to be an effective teaching style in the Korean market, have continued to be a competitive market commodity even in the Japanese market. At the same time, the market expansion has forced English language schools to reconfigure themselves. English schools, originally exclusively for use by Koreans, have tried to adopt de-Koreanization efforts, including changes in their organization, services, educational programs, and even school facilities. This has led to the schools becoming cornerstones for global ethnic businesses. This qualitative transformation has, to date, received little attention in past studies on ethnic businesses; in this sense, the Korean English language businesses in the Philippines are new exemplars of highly groundbreaking and innovative business practices in the age of globalization and mobility.

Further, these ethnic minority businesses deserve special mention as they have succeeded in establishing sound relationships with the Philippine government. The government, taking advantage of Korean entrepreneurship for continued growth, has further promoted the commodification of Philippine English as a form of education tourism by combining English education and tourist attractions. Such a government intervention, though understood to be a means of state regulation to raise the quality and standard of the Philippine English education industry, was intended to establish the Philippines as a popular destination in Asia for learning English. The promotion of the Philippines as a host society that welcomes ethnic businesses represents the Philippine way of pursuing economic development toward inclusive growth (Kuroda, 2017). The interplay between the host country and ethnic minority businesses can be analyzed as a transnational process of mutual empowerment.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the PCO editorial staff, the 2 anonymous reviewers, and Kazuhiro Ota for their insightful and valuable comments and that greatly improved an earlier draft of this article. He is also grateful to Ryohei Kaneko, Shoji Mori, Tomoya Noguchi, and Hidenobu Oguni for their generous support to make his field research at Baguio possible. His research in the Philippines was supported by a generous grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (KAKENHI 17K03272).

References

ABS-CBN News (2008) More Korea towns rising in PR (20 September 2008). Available from https://news.abs-cbn.com/features/09/20/08/more-korea-towns-risring-rp (Accessed 19 June 2019)

Asia Development Bank (2007) Moving Toward Knowledge-Based Economies: Asian Experiences. Manila: Asia Development Bank.

Baguio Times (2015) A list of Korean business enterprises (15 January 2015). Available from https://baguioinfo.tistory.com/category/%EB%82%98%EC%9D%98%20 %EB%B0%94%EA%B8%B0%EC%98%A4%20%EC%83%9D%ED%99% (Accessed 19 June 2019)

Baily , T., and R. Waldinger (1991) Primary, secondary, and enclave labor markets: A training system approach. American Sociological Review 56(4): 432–445.

Bamgbose, A. (2001) World Englishes and globalization. World Englishes 20(3): 357–363.

Barros, M. (2006) The Koreanization of Baguio: Issue of acculturation. In Asian Cultural Forum , pp.1–10. Available from

http://cct.pa.go.kr/data/acf2006/multi/multi_0401_Mae%20P.%20Barros.pdf (Accessed 19 June 2019)

Bernardo, A. (2004) McKinley’s questionable bequest: Over 100 years of English in Philippine education. World Englishes 23(1): 17–31.

Boancich, E. (1973) A theory of middleman minorities. American Sociological Review 38(5): 583– 594.

Board of Investments (2009) Proposed Tourism Roadmap for Global Competitiveness, Prepared

for WG-GIC Meeting with Development Partners. Manila: Board of Investments.

Bolton, K. (2008) English in Asia, Asian Englishes and the issue of proficiency. English Today 24(2): 3–12.

Burton-Jones, A. (1999) Knowledge Capitalism: Business, Work, and Learning in the New

Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cebu Daily News (2015) English program lacks support from academe (4 February 2015). Available from

https://cebudailynews.inquirer.net/51021/english-program-lacks-support-from-academe (Accessed 19 June 2019)

Chin, K., I. Yoon, and D. Smith (1996) Immigrant small business and international economic linkage: A case of the Korean wig business in Los Angeles, 1968–1977. International

Migration Review 30(2): 485–510.

Choe, H. (2016) Identity formation of Filipino ESL teachers teaching Korean students in the Philippines. English Today 125(1): 5–11.

Choi, H., and E. Kim (2017) Educational exodus: Stories of Korean youth in the U.S. Social

Sciences 6(4): 1–15.

Department of Tourism (DOT), Republic of the Philippines (n.d.) Learn English in the Philippines. Manila: Department of Tourism.

Department of Tourism (DOT), Republic of the Philippines (2009) Tourism Industry Performance:

Report on the Performance of the Arroyo Administration, House Oversight Committee.

Manila: Department of Tourism.

Department of Tourism (DOT), Republic of the Philippines (2011) The National Tourism

Development Plan: Strengthening the Philippines Strategic Planning Process, Prepared for 6th UNWTO Executive Training Program, 25–28 June 2011. Manila: Department of Tourism.

Errighi, L., C. Bodwell, and S. Khatiwada (2016) Business Process Outsourcing in the Philippines:

Challenges for Decent Work (ILO Asia-Pacific Working Paper Series). Bangkok: ILO.

Finch, J., and S. Kim (2012) Kirogi families in the US: Transnational migration and education.

Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 38(3): 485–506.

Forey, G., and J. Lockwood (2006) “I’d love to put someone in jail for this”: An initial investigation of English in the business processing outsourcing (BPO) industry. English for Specific

Purposes 26: 308–326.

Fukuda, T. (2012) The Social World of Transnational Pakistani Migrants: From Immigrant Workers

to Immigrant Entrepreneurs. Tokyo: Fukumura Syupan. (in Japanese)

Fukuda, T. (2015) Ethnic businesses and transnational kinship of Pakistani migrants in Japan. Mita

Journal of Sociology 20: 38–51. (in Japanese)

Global Human Resource Development and Promotion Committee (2011) An Interim Report on Global Human Resource Development and Promotion Committee. (in Japanese) Available from https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/singi/global/110622chukan_matome.pdf (Accessed 19 June 2019). GMA-NEWS (2009) 33 Baguio-based Koreans granted special visas (29 April 2009). Available from

https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/news/nation/159080/33-baguio-based-koreans-granted-special-visas/story/ (Accessed 19 June 2019)

Gomez, J. A. (2011) The Korean diaspora in the Philippine cities: Amalgamation or invasion. In J. Hou (ed.), Transcultural Cities: Symposium Proceedings, pp. 48–55. Seattle: University of Washington.

Gonzales, A. (1981) Language policy and language-in-education policy in the Philippines. Annual

Review of Applied Linguistics 2: 48–59.

Gonzales, W. (2017) Philippine Englishes. Asian Englishes 19(19): 79–95.

Han, J. (2018) Pachinko Pinball Game Industrial History. Nagoya: Nagoya University Press. (in Japanese)

Heller, M. (2003) Globalization, the new economy, and the commodification of language and identity. Journal of Sociolinguistics 7: 473–492.

Heller, M. (2010) The commodification of language. Annual Review of Anthropology 39: 101–14. Higuchi, N. (2007) Food crossing the border: Businesses of Muslim staying in Japan and haral

food industry. In N. Higuchi, N. Inaba, K. Tanno, T. Fukuda, and H. Okai (eds.), Crossing the

Border: The Sociology of Muslim Migrants Living in Japan, pp.116–141. Tokyo: Serikyusya.

(in Japanese)

Higuchi, N. (2010) Ethnic businesses in Japan: Comparing different groups. Asia Pacific Review 7: 2–16. (in Japanese)

Higuchi, N. (2012) Ethnic Businesses in Japan. Tokyo: Sekaishisousya. (in Japanese)

Higuchi, N., N. Inaba, K. Tanno, T. Fukuda, and H. Okai (Eds.) (2007) Crossing the Border: The

Sociology of Muslim Migrants Living in Japan. Tokyo: Serikyusya. (in Japanese)

Higuchi, N., and S. Takahashi (1998) Ethnic business of Brazilians in Japan: Microstructural development for entrepreneurship and ethnic market concentration. Iberoamericana 20(1): 1–13. (in Japanese)

Hoshino, T. (2013) A Best Way of Learning English in Asia. Tokyo: Syuwa System. (in Japanese) Hurh, W., and K. Kim (1984) Adhesive sociocultural adaptation of Korean immigrants in the U.S.: An

alternative strategy of minority adaptation. International Migration Review 18(2): 188–216. Igno, J., and M. Cenidoza (2016) Beyond the “fad”: Understanding Hallyu in the Philippines.

International Journal of Social Science and Humanity 6(9): 723–727.

JETRO Manila Center (2006) Philippine’s Call Center Industry Research Report. Manila: JETRO Manila Center. (in Japanese)

JETRO Manila Center (2012) Research on the Institution of Education Industry in the Philippines. Manila: JETRO Manila Center. (in Japanese)

Jones, R. (2013) Education Reform in Korea (OECD Economics Department Working Papers 1067). Paris: OECD Publishing.

Kachru, B. (2005) Asian English beyond the Canon. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. Kawahara, T. (2002) Languages and Language Policies in Insular Southest Asia: Focusing on the

Philippines and Malaysia. Tokyo: Shunpusya .

Kim, B. (2015) The English fever in South Korea: Focusing on the problem of early English education. Journal of Education and Social Policy 2(2): 117–124.

Kim, D. (2016) Geographical imagination and intra-Asian hierarchy between Filipinos and South Korean retirees in the Philippines. Philippine Studies 64(2): 237–264.

Kim, K., and W. Hurh (1985) Ethnic resources utilization of Korean immigrant entrepreneurs in the Chicago minority area. International Migration Review 19(1): 82–111.

Kim, S., and W. Ma (Eds.) (2011) Korean Diaspora and Christian Mission. Oregon: Wipf and Stick Publishers.

Kirkpatrick, A. (2012) English in ASEAN: Implications for regional multilingualism. Journal of

Multilingual and Multicultural Development 33(4): 331–344.

Kobari, Y. (Ed.) (2018a) Interdisciplinary Study of Japan-the Philippines’ Relationship and Its

Change Caused by the Commodification of Service. ?? : Asian Institute, Asia University. (in

Japanese)

Kobari, Y. (2018b) The commodification of Philippine English: From field research. In Y. Kobari (ed.), Interdisciplinary Study of Japan: The Philippines’ Relationship and its Change Caused

by the Commodification of Service, pp. 5–28. Tokyo: Asian Institute, Asia University. (in

Japanese)

Kobayashi, K. (2017) Sociology of Early Study Abroad: Korean Children’s Crossing National

Boundary. Kyoto: Syouwado. (in Japanese)

Kuroda, H. (2017) Toward inclusive growth in Asia: Keynote speech at the global think tank summit 2017 in Yokohama. Tokyo: Bank of Japan. Available from

https://www.boj.or.jp/en/announcements/press/koen_2017/data/ko170502a.pdf (Accessed 19 June 2019)

Kutsumi, N. (2007) Koreans in the Philippines: A study of the formation of their social organization. In V. Miralao and L. Makil (eds.), Exploring Transnational Communities in the Philippines, pp.58–73. Manila: Philippine Migration Research Network and Philippine Social Science Council.

Kwak, M. (2013) Immigrant entrepreneurship and the opportunity structure of the international education industry in Vancouver and Toronto. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 22(4): 547–571.

Kwak, M-J., and D. Hiebert (2010) Globalizing Canadian education from below: A case study of transnational immigrant entrepreneurship between Seoul, Korea and Vancouver, Canada.

Journal of International Migration and Integration 11: 131–53.

Kwon, E. (2004) Financial liberalization in South Korea. Journal of Contemporary Asia 34(1): 70–101. Lee, M. (2006a) Invisibility and temporary residence status of Filipino workers in South Korea.

Journal for Cultural Research 10(2): 159–172.

Lee, M. (2006b) Filipino village in South Korea. Community, Work and Family 9(4): 429–440. Lee, Y., and H. Koo (2006) Wild geese fathers and a globalized family strategy for education in

Korea. International Development Planning Review 28(4): 533–553.

Lockwood, J., G. Forey, and H. Price (2008) Englishes in the Philippine business processing outsourcing industry: Issues, opportunities and initial findings. In M. Bautista and K. Bolton (eds.), Philippine English: Linguistic and Literacy Perspectives, pp. 219–242. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Lorente, B. (2013) The Grips of English and Philippine language policy. In L. Wee, R. Goh and L. Lim (eds.), The Politics of English: South Asia, Southeast Asia and the Asia Pacific, pp.

187–203. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Lorente, B. (2018) Scripts of Servitude: Language, Labor Migration and Transnational Domestic

Work. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Martin, I. (2008) Fearing English in the Philippines. Asian Englishes 11(2): 76–79.

Masselink , L., and S. Lee (2013) Government officials’ representation of nurses and migration in the Philippines. Health Policy and Planning 28: 90–99.

Mimamikawa , F. (2002) Racial and ethnic formation and Asian immigrants in America: Reconsidering ethnic business. In T. Miyajima and T. Kajita (eds.), Minority and Social

Structure, pp.45–66. Tokyo: the University of the Tokyo Press. (in Japanese)

Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), Embassy of the Republic of Korea in the Republic of the Philippines (n.d.) The number of Korean migrants in the Philippines for 2009, 2010, 2012, 2015, 2016. Available from

http://overseas.mofa.go.kr/ph-ko/brd/m_3660/list.do (Accessed 19 June 2019)

Murata, K., and J. Jenkins (2009) Global Englishes in Asian Contexts: Current and Future Debates. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Nagano, S. (Ed.) (2010) Korean Economic Development and the Role of Japanese-Korean

Entrepreneurs. Tokyo: The Iwanami Shoten. (in Japanese)

Nakagawa, Y. (2015) Korean students’ early study abroad for English language learning: The changes and the current situation. The Annual Bulletin of the Humanities 45: 157–187. (in Japanese) Nakagawa, Y. (2016) South Korea early study abroad to learn English and study abroad agencies: A

case study of Toronto, Canada. Korean Culture 15: 3–25. (in Japanese)

Nelle, E. (n.d.) New Tourism Products. Manila: Department of Tourism, the Philippines.

Noh, S., A. Kim, and M. Noh (2012) Korean Immigrants in Canada: Perspectives on Migration,

Integration, and the Family. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

OECD (1996a) The Knowledge-Based Economy. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD (1996b) Territorial Development and Human Capital in the Knowledge Economy: Towards

A Policy Framework. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD (2010) Open for Business: Migrant Entrepreneurship in OECD Countries. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Ota, H. (2011) Extremely Reasonable English Study in the Philippines. Tokyo: Toyokeizai Shinposya. (in Japanese)

Park, J. (2009) “English fever” in South Korea: Its history and symptoms. English Today 97(25): 50–57. Park, S., and N. Abelmann (2004) Class and cosmopolitan striving: Mothers’ management of

English education in South Korea. Anthropological Quarterly 77(4): 645–672.