The

What Can Japan Contribute

to Educational Development?

Case of Education in India: A Survey of Problems and Prospects

by David B.

Willisand

HiroyuleiHa tashima

Abstract

The `educational crises' which are perceived to exist in Japan and America pale in significance to those found in developing countries such as India, where the meaning of the word `crisis' becomes all too clear. This paper proposes that the `hard' aid traditionally given to developing countries by Japan (in the form of bridges, dams, etc.) now needs to be supplemented by `soft' aid, particularly that aid which draws from the rich experience Japan has had in the exceptional development of its skilled human resources. This marks a significant redirection of investment away from infrastructural capital projects and towards a new focus on

the development of human capital.

Moreover, the fundamental shift in the world's attention from the struggles of capitalism/communism (US/USSR) to those of havesXhave-nots (NorthlSouth) requires a new and broader democratic approach

that is consciously global rather than simply national or bilateral. The 21st Century will see the analysis of developmental issues on a world scale.We have truly entered a post-colonial era, and those nation-states which most effectively assert a vision of the post-colonial state deserve our attention. In their own ways, In-dia and Japan are important examples of the post-colonial state.

Japan, in particular, will be seriously challenged in the new century by the need to analyze developmental issues on a world scale. Unilateral or bilateral thinking is simply not enough. That the developmental issues facing hurnanity are already serious, with long-term, far-reaching consequences, cannot be over-stated. Since all countries today are interlinked, and therefore interdependent, the successes or failures of other educational systems will have an impact on all of us. In order to begin to appreciate the complexities and potentialities involved for Japan (and for other developed countries) , this paper will focus on one case, that of education in the Republic of India.

Introduction

Japanese and American scholars have recently focused intensively on each other's

perceived to exist in their respective societies (Cummings et al., 1986). These problems pale

in significance, however, to those found in developing countries such as India, where the

meaning of the word `crisis' becomes all too clear (Coombs, 1985; Fagerlind and Saha, 1983).

It is the suggestion of this paper that the `hard' aid traditionally given to developing countries by Japan (in the form of such projects as roads, bridges, dams, and so on) now needs to be supplemented by `soft' aid, particularly aid which draws from Japan's rich ex-perience with the exceptional development of her skilled human resources. This marks a

significant redirection of investment away from infrastructural capital projects and

towards human capital programs. Learning here is seen as essentially a cultural process (in fact, the central cultural process). As Psacharopoulos has noted (1988), Japan's em-phasis on education since the Meiji Period set the foundation for its economic miracle. The cultural components of this emphasis offer valuable lessons for developing countries.

The problems and prospects of education in the developing world deserve our

atten-tion, not only for humanitarian reasons, but for the new light which they may cast on the educational systems of `developed' societies. Such research goals are not so far-fetched as they may at first seem. Few Americans would have imagined twenty years ago, for exam-ple, that what was then considered a developing country would later become one of the paragons of human capital investment and world educational achievement. That country is Japan.

When educational problems are examined comparatively, we also note that cultural

transmission and the diffusion of ideas have invariably had a significant impact on both the giver and receiver in the process. The experience of India may have particular conse-quences for Japan, for example, related as these two civilizations are philosophically,

politically, and culturally (Bhanote, 1985) . Although all of these areas are related to human

capital theory, they have been ignored by economists.

Traditionally, economists have treated education at a distance as an "investment," an investment measured by the rate of return. This rate of return is commonly defined as a combination of the private rate of return (wage earnings) and the public rate of return

(social earnings, as measured by such indices as reduced mortality rates following an

in-crease in female education). Comparative education, cultural and social anthropology bring other dimensions to the study of educational problems in developing countries.

Their perspectives are different from those of economists, who have been dominated by the production-function paradigm (Little, 1991). Moreover, these approaches suggest the scope for international collaboration, notably in this case concerning aspects of Japanese

David B, urillis and Hiray"lei Hatashima

soft-aid relevant to the Japanese educational experience.

Of special note is the fact that these two countries, Japan and India, are the most ex-perienced democracies outside the Western cultural orbit. Except for the brief

`Emergen-cy' period in the 1970s, India has proudly maintained its democracy while neighboring countries in South, Southeast, East and West Asia have been virtual garrison states.

Japan, likewise, takes great pride in its democratic traditions and consensus

decision-mak-ing.

Moreover, the fundamental shift in the world's attention from the struggles of capitalism/communism (USIUSSR) to those of haveslhave nots (North/South) requires a new and broader democratic approach that is consciously global rather than simply

na-tional or bilateral (Brandt, 1980) . The 21st Century will see the analysis of developmental issues on a world scale (Murakami and Kosai, 1986; Mannari and Befu, 1983). Following the events of 1989--92, it can be said that we have truly entered this erala post-colonial era, and those nation-states which most effectively assert a vision of the post-colonial state deserve our attention. In their own ways, India and Japan are important examples of this

post-colonial state.

Japan, in particular, will be seriously challenged in the new century by the need for

analyses of developmental issues on a world scale. Unilateral or bilateral thinking is simply

not enough. That the developmental issues facing humanity are already serious, and with long-term, far-reaching consequences, cannot be over-stated.

Since all countries today are interlinked, and therefore interdependent, the successes or failures of other countries' educational systems will have an impact on all of us. It is

gradually dawning on policy-makers that our own socio-economic development and

political stability are directly affected by what happens half a world away. Japan has much

to contribute to the study of these issues, particularly in terms of shaping policy

prescrip-tions for this, one of the most important building blocks for developing countries:

educa-tion.

In order to begin to appreciate the complexities and potentialities involved for Japan (and for other developed countries), let us focus on one case, that of education in the late 20th Century in the Republic of India.

Indian Education Today

late 1980s and early 1990s made education a high priority, but substantial money has actual-ly begun flowing down to schools at the grass-roots level. The urgency that is felt can be

seen in the three topics concerning education that are of the.most public interest in India in

the early 1990s: AIDS education, non-formal education and the role of women's education

in development (Personal communications from Indian scholars, 1990---9. 3, anticipated by Joshi and Menon, 19. 86; Jayagopal, 1985; Illich, 1981; Adiseshiah, 1981; Coombs and Manzoor, 1974). Yet these topics are incendiary in nature, drawing attention to a host of gender and class-related

pro-blems which dramatically challenge the Indian status quo.

Moreover, public attention to these topics, while vigorously supported by the mass media, is at odds with the views of most policy-makers. And with economists in particular.

From an economic policy-maker's point of view the two problems confronting Indian education today are mass illiteracy among the young and a shortage of technically

qualified people. Both these problems create bottlenecks for Indian economic growth that

have been addressed by a variety of new programs designed by the government. The New

Education Policy (NEP), Operation Blackboard, and the Navodhaya Schools Movement

formulated in the mid to late 1980s are the most visible of these public programs (National

In-stitute of Educational Planning and Administration, 1987; Ministry of Human Resource Development, 1986;

Nagaraju, 1985; National Council of Educational Research and Training, 19.85). They represent a

strong emphasis on educational remedies for fundamental `human capital' problems, while

avoiding direct confrontation with the more controversial topics mentioned above. It

should be noted that the direction continues to be elitist (witness continuing support for

the Navodhaya Movement, while Operation Blackboard has languished).

Foremost of the new governmental programs has been the New Education Policy

(NEP), which ostensibly intends to provide an education for rural reconstruction andsocial change, panicularly at the primary and non-formal levels. Operation Blackboard

was a rush program within the NEP framework that was designed to provide all schools

with at least one blackboard, a rather grim statement of the condition of mass education.

The Navodhaya Schools Movement has been the most far-reaching experiment of the new

programs, however, a nation-wide attempt to identify and nurture excellence in youths of all backgrounds, rich or poor, through a system of special residential schools. Eventually, every district of every state is to have one of these schools.

An aggressive recruiting program (especially in rural areas), scholarships for poor students, and the utilization of top teacher talent are features of these Navodhaya schools.

David B. Willis and Hiroyuki Hatashima

represents a departure from the traditional idea of Indian education as serving the masses,

although the other programs of the NEP are intended to strengthen just this kind of

democratic, egalitarian-based education.

In fact, India's traditional rhetorical support for mass education has masked a more significant on-the ground trend that reveals the failure of mass education and the promo-tion of elite educapromo-tion from which, it might be argued, only a few people benefit. From the

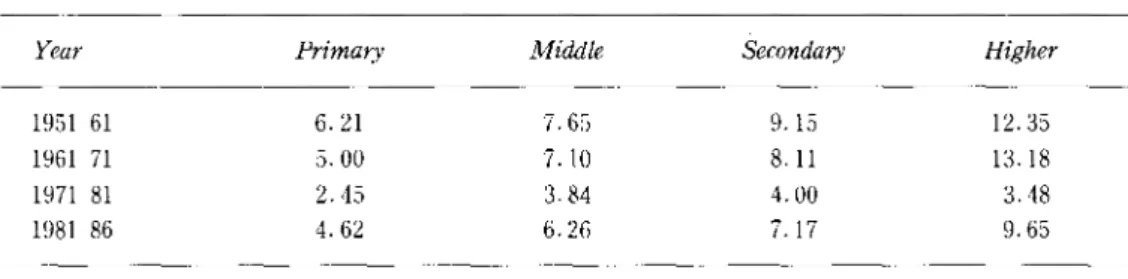

perspective of available statistics (Table 1, from Suri et al, 1990) mass education is not

expan-ding as fast as education for elites. Despite the government's effort to introduce univer-salization of education, the growth of the enrollment ratio in India is actually constantly dropping. As the table shows, primary education has had the lowest growth in enrollment ratio while higher education has had the highest rate of growth i'n India.

Table 1

Growth of Education in India ( `)(o )Year Primary Midale Secondary Higher

1{ 51-61 1961-71 1971 -81 19. 81 -86 6.21 5. 00 2.45 4.62 7.65 7. 10 3.84 6.26 9.15 8. 11 4.00 7.17 12.35 13. !8 3,48 {.65 Source: 1

2

. Education in India, Ministry of Education, New Delhi.

. UGC Reports, UGC, New Delhi.

Nevertheless, it is remarkable that India, with its vast population pressures and an educational infrastructure inherited from a 19th Century British colonial system has been

able to maintain a viable public educational system (Desai, 1986; Altbach and Kelly, 1978) . Seen

in this light, the accomplishments of public schooling in India, particularly at the

elemen-tary and tertiary stages, are impressive, containing possible lessons which could be

transferred to other developing countries.

Yet the contradictions between elitist and populist views concerning India's educa-tional problems remain. They are further complicated by other voices, notably those of

many Indian educational scholars. Unfortunately, many of these scholars have focused

their research efforts on educational issues as if Indian education was at a developmental stage similar to today's England. While this perspective has produced a voluminous and erudite literture, a number of Indian educators view such scholarship as seriously misguid-ed, aimed primarily at consolidation of an educational system which does not in fact exist.

For these critics the appropriate focus of research efforts is on seeing the educational system as being at a formative rather than at a climax stage.

This critique represents a significant shift among Indian educators in the direction of more realistic, more sharply-defined views of educational goals and content. There is a

perception among Indian educators today that three important problems confront Indian

education:

1 ) the meaning and goals of education

2) the actual needs of education

3) the imPlementation of educational plans

Furthermore, these problems are complicated by a range of factors related to India's

status as a `soft state' (a term used by Gunnar Myrdal and others to signify variants of social

in-discipline; see Myrdal, 1968, 1970), the lack of relevance between what is taught and future employment, and India's many economic, cultural, and linguistic disparities.

Of course, these are problems common to many developing countries. What

distinguishes India is both the enormous scale of the problems encountered and the energy with which possible solutions have been so freely debated and then attempted. India thus provides a wide range of experiences as well as an important venue for exploring whether and in what contexts the Japanese educational experience merits examination as a model for developing countries. But before we move into that discussion, the stage must be set by providing an overview of contemporary social and political problems affecting India's educational system.

Political and Social Problems Affecting Indian Education

What is the meaning of education in the late Twentieth Century for a developing coun-try like India? What goals are most appropriate for a national educational system? Does public education have any relevance for the future? Such topics are currently the subject of heated discussion in India's media, much as they have been for the better part of the 1980s and early 1990s in Japan and the United States.

Viewed from one perspective, the involvement of local politics in the arena of educa-tion has been a serious stumbling-block to the central government's attempts to make

In-dia's schools viable as integral elements for national development. Seen from another point of view, however, the cultural hegemony of a strong central power robs regional cultures of the right to determine their own patterns of socialization and their own

David B. PVillis and Hirayuki Hattzshima destinies.

Since education in India is a function of the states and since the states in India were

'

formed on the basis of language and/or culture, a fierce and suspicious rivalry has

developed between the republic's central government and its states, especially those with particularly strong cultural identities. The recent experiences of the states of Punjab,

Tamil Nadu, and Assam are only the most prominent of many examples. While diversity

has its advantages, it also has severe limitations, at least from the point of view of national

consolidation. Japan again provides a counter-point example here.

The most serious problem facing education in India continues to be the question of

language, specifically which medium of instruction is best suited for use in the nation's schools. Officially, schooling is supposed to be provided under the recognized `Three Language Formula' : the national language (Hindi), the link language (English), and the

regional language (Local Mother Tongue).

English, inherited from the British and disparaged because of its colonial connections, has nevertheless been the dominant factor in India's continuing political and economic

uni-ty, functioning to maintain India's identity as a single poliuni-ty, as its lingua franca, and as the

prestige language of education. The main challenger, Hindi, is seen as a possible replace-ment for the future, but past attempts to impose it on the entire country have resulted in serious political instability (for example, the threat of the Tamils to secede from the

In-dian Union) . Ironically, the advent of national television with its frequent Hindi

programm-ing and advertisprogramm-ing appears to be hastenprogramm-ing the process of Hindi adoption much faster

than any official policy of forcing Hindi on unwilling populations.

But for now the passionate attachment non-Hindi speaking peoples have for their own languages acts as a brake on the development of a national language. The alternative is

either promotion of the regional tongue, which Hindi-speakers view as undermining

na-tional integration and nana-tional unity, or the use of English (the language of colonial-era

op-pressors) as the medium of instruction.

In official eclipse for some years as the language of education, English-language

education has recently been making a serious comeback, often offering significant

competi-tion to the public educacompeti-tion provided by the states in their various local languages. The

suc-cess of English is largely due to the higher status accorded to those job-seekers who know English. India's elite has, for the most part, for instance, been trained exclusively in

English-medium schools.

instruc-tion now occupies, as the memory of colonial dominainstruc-tion fades, can be seen as a potentially

unifying factor for India. It is another key indicator of the assertion of India's identity as a

post-colonial state, this confidence in a link language which over-rides that language's

former status as a tool of the colonial oppressor. English is of course also an important

com-ponent of international .understanding (and therefore of India's place in the world). Moreover, the fact that many of India's elite learn it as a second language and that (nearly twenty million claim it as their mother tongue) means that tens of millions of Indians are bilinguallbicultural, an undoubted advantage for the 21st Century.

Yet, for obvious reasons, English cannot be the sole medium of instruction for India. In reality, those educated in English remain the elite while almost everyone else, those

who learn in schools where the medium of instruction is either Hindi or a regional

language, are left to a future limited in scope and opportunity. The question of the role of language in education is thus indeed serious for India's future.

The next pressing problem for Indian education involves what has most recently been

termed rural integrationldevelopment. The very clear polarization between haves and

have-nots within India mirrors the world system of have and have-not nations. What

hap-pens at this level will likely have implications for the world system. Although this split can

be found in the cities, the greatest gap is between the cities and the countryside. Moreover, a number of our Indian informants have stated that, while Poverty is being eliminated in India, ine4ualities are growingsharPly. The challenge to education, therefore, is not the elimination of poverty Perse, which is seen as gradually being accomplished, but the elimination of inequalities. The charge of schools is thus to be directly involved in

social change, a difficult task.

This objective is not only politically and socially sensitive, but is further complicated

by the needs of youths seeking employment (and thus the demand for vocational

educa-tion) as well as the large numbers of adults requiring basic literacy and other functional training (non-formal and adult education). In terms of sheer numbers the needs of these sections of the populace require special attention from the Indian educational authorities.

Throughout India there is also tremendous concern about the over-emphasis on

ex-aminations as the single criterion for academic achievement and selection. Comments such as the following were given by Indian educators when examinations were discussed during

a research visit:

``Students don't learn to think on their own.'' ``They are only glorified memory machines.''

David B. PVillis and Hiroyuki Hatashima ``The totality of their education is questionable."

These are familiar echoes for those scholars interested in Japanese education. India has

possibly even gone beyond Japan in its `examination-hell,' if we can judge from the mindless character of many of the examinations (e.g., questions about 16th century

English kings answered by 20th century Bengalis), the large number of tutoring

academies, and the desperate moves which students resort to in order to get the rightmarks.

The meritocracy of the British has been replaced by a credentialism (what Japanese would call gakurelei-shakai) whose sole goal is a degree, preferably from a `name' universi-ty, a degree gotten by whatever means, fair or foul (Collins, 1979; Dore, 1976). The impor-tance of a degree is so great that one occasionally meets individuals in India who hand out

name-cards which say something like

Ravi Kumar, B.A., M.A. (Failed)

Even having studied a subject without passing the test places one higher in the competi-tion for jobs. Naturally, such pressure results in considerable abuse of the educacompeti-tional system. The single-minded pursuit of high test scores results in corruption (buying of tests and teachers) , memorization of information without the accompanying ability to ac-tually think about what has been taught, and evenac-tually an evaporation of confidence in the educational system and learning. This is perhaps the logical end-point for a society more concerned with `degree qualifications' than with education: The quality of learning is compromised by examinations designed for selection and allocation (Little, 1991, p.2). The experience of India thus provides valuable lessons for Japan's future should it continue on its present path of relentless emphasis on examinations (or for America, which is focusing more and more on testing a la Japan as a panacea for educational ills) .

Moreover, in India, as in Japan, the quality and amount of an individual's education is directly related to the availability of resources for commercially marketed after-school study. In Japan this meansjuku (cram schools) and katei kyoshi (home tutors) , while in In-dia the same features are manifested as `tutoring academies' and `tuitions'.

What is different is the relation between credentialism/gakureki-shakai on the one

hand and the expansion of mass-education on the other. Both countries can be seen as hav-ing an extreme form of `gakureki shakai,' with all of the familiar features that such a system entails - cram schools, old boy (OB) networks, and an examination `hell.' However, Indian education leads to an elitist focus, while the Japanese experience has meant a successful education for the vast middle range of the population, at least until

recently. It is clearly one of the major `secrets' behind the Japanese economic miracle. Mass education for Japan has been a great success, whereas for India it is something that has withered on the vine.

Education in India, especially at the higher levels, is thus clearly linked to what is

widely seen as an increasingly polarized social stratification. `Education' serves not only as

a vehicle for upward mobility but as a measure of the widening gap between rich and poor, between haves and have-nots. The meaning of education for the village poor, for women, and for most employers has little in common with the.traditional goals of liberal educators, who see education as designed to provide an individual with a wide range of cultural com-petencies. In this light, education can actually be viewed as having dubious value depen-ding upon the circumstances in which it is used.

The oppressed often see those from their ranks who have had an `education'as

cultural misfits, as people looking for jobs which do not exist in their villages. At the same

time these `over-educated' people are an economic burden on their village families. Nor

are these `educated' poor suited for those jobs which do exist in rural settings, since their

expectations have been skewed heavily by urban biases. Employers in the cities, who are themselves often prejudiced in favor of workers from urban areas, hardly look favorably upon educated rural people, especially as there are many educated job-seekers from urban

backgrounds.

Implementation of educational policy in this context thus runs into problems of linkage between employment, income, and education. Although there is some evidence of

a long-term link between higher income and greater education, much of the data available concerning such linkage is skewed by the fact that individuals who participated in the study already had initially high socio-economic status.

Other recent research in India which started with a broad representative sample has actually demonstrated a disconcerting positive connection between a lacle of education

(yes, less education) and higher wages! This is not so surprising if we consider the

statistical impact of the high numbers of educated unemployed, however. In any event, the

pressures of demographics and the need for at least a survival income have meant a

dramatic drop-out rate from formal education, particularly after the third year of

elemen-tary school and especially in rural areas (Safaya, 1986; Pareek, 1982; Patil and Patil, 1982; Shingi,

1980).

Economists are right when they consider the costs of education. What they often

David B. veillis and Hiroyuki Hatashima

ed for schooling, but also for the family's opportunity costs. Children often support their families economically through labor. Sending them for a full-time education means a loss of income or labor power in the household. Since the principal asset of the poor is labor time, there is thus a hard economic decision facing families in poor households where they must compare education as `investment' and education as `cost.' Any aid to the education

of a developing country must therefore consider both the `real' costs to parents and the

`op-portunity' costs with which they are also faced (if and when they send their children to

school). Here the Japanese experience may be inappropriate, since the less stratified

nature of Japanese society has made special help for the poor unnecessary.

Governmental response to this problem in India has been to pass laws requiring

com-pulsory attendance. These laws are not enforced, however, for both political reasons (votes) and economic pressures (the need for families to have as much income from as

many sources as possible) . It is thought by some people to be more humanitarian not to

force a child to go to school when he or she can be employed as a worker in a nearby

restaurant or match-factory, thus providing much-needed economic support for the family. As Pscharopoulos (1988) has shown, however, there is a very strong argument for the

relationship between "investment" and education. We would like to emphasize the social arrangement toward this kind of "investment" in Japan. Cultural and social values suppor-ting a preference for this kind of investment rather than for the immediate return of "child

labor" seems one of the important aspects of the Japanese experience in the spread of

basic education which might be relevant to India and other developing countries. But this requires a long-term perspective.

In the short term, the linkage between literacy and functionality, between schooling and jobs, is thus less important than `who you know' and the credential, the degree, you hold. Merit counts for little in a country where connections and personal networks usually are of first consideration when it comes to employment opportunity.

Education in the classic sense of skills preparation is thus actually peripheral to employment. The degree (or title) carries weight only insofar as it signifies publicly that the `correct decision' was made by the employer. The parallels to Japan's own system of gakubatsu (educational cliques) are striking. It is not what you have learned, but that you

have passed the `right' test, attended the `right' university and received the `right' degree.

The tremendous wastage and inappropriate allocation of human resources that is

at-tendant in this process are only gradually being recognized. Not only is there a nearly total

employed by schools and universities is enormous compared to the number of teachers. A typical case at one large South Indian university which one of the researchers visited was

1500 non-teaching staff for 500 teachers. The system was characterized by informants as designed not for the purpose of education but for the creation of more and more red-tape, in the Indian idiom `an empire of paper.'

As in most countries, the bureaucracy continues to grow but the efficiency of this bureaucracy is highly questionable. The widely-held belief that a civil service position is

the most desirable job of all, both for its benefits and for its security, is hardly surprising.

Significantly, teaching is not a civil service job, as it is in Japan. In this context, what lessons might there be in the apparent greater effectiveness and efficiency of Japanese education?

Future Prospects: The Possible Contributions of Japan as a Model

The lessons which Japan could provide for developing countries such as India lie in many areas, but what appears to be especially notable is job placement, the link between schooling and work, and the continuing education provided in the work-place. Inservice

education programs abound in Japan, particularly in the critical first year or two of

employ-ment. This is a little-studied area of the Japanese educational experience which could make enormous and very significant contributions as soft-aid for education in developing

countries (Dore and Sako, 1989).

The linkage between schooling and work is also demonstrated by teachers, whose

preparation, recruitment, and placement are critical to future generations. Japan has

shown remarkable foresight by making teaching careers highly attractive. As is well

known, there are typically five applicants for every teaching position. In desirable areas the ratio may be 1:10. In India today, on the other hand, teaching is ajob of last resort, a

job for those who have failed to obtain a position at a bank, a large corporation, or with the civil service (Seshadri, 1986; Shamsuddin, 1986; Pillai and Mohan, 1985).

Moreover, the Japanese experience in the following key areas could also provide

useful lessons for India:

1) elementary education

2) the development of educational norms

3 ) the integration of rural areas into the mainstream of national education

David B. Willis and Hirayuki Hatashima

rather than achieved, there has been little motivation to achieve in school or anywhere else. It is only in the competition with other nations such as Pakistan and China that a sense of national purpose has even begun to be operationalized. Again, the lesson of Japan in providing a functional education directly related to national development and national

purpose could be useful for India (Leestma and Walberg, 1992, 1987; Rohlen, 1983; Dore and Sako,

1989; Shields, 1989; White, 19. 87; Duke, 1986; Stevenson et al., l986; Cummings, 19. 80).

Of perhaps most concern for Indian educators and the general public, though, is the degradation or decline of moral values, something attributed to such factors as secularism

and the breakup of the joint family (Ruhela, 1986; Seshadri, 1981). The key point here is how

those Indian educators whom we interviewed perceived what was happening. Indian socie-ty was characterized by many of these informants as having experienced a dramatic. shift in values in the last fifteen years, from a commonly-held belief in hard work as the road to

success towards a materialistic, selfish and aggressive set of values. There is less and less

regard for the means in reaching the ends of material satisfaction. There is a familiar echo

here in concerns expressed in Japanese media about the younger generation and their

values. Values are an area of common concern to India, Japan, America, and other nations

(Cummings, Tomoda, and Gopinathan, 1988).

These are some of the challenges facing Indian education. What are the prospects?

First, the growing sense of national purpose in India is encouraging. This is evident in In--dians' pride in their nation as a regional power, in the increasingly robust yet also clearly

in-terdependent Indian economy, and in the Central Government's reactions to the crises in

the Punjab and elsewhere. Ultimately, the benefits of diversity in terms of a multiplicity of talent and ideas could result.

It should not be forgotten that India has contributed greatly to world civilization. A

culture which gave the world the concept of zero, without which modern mathematics and technology could not exist, not to mention numerous religious and philosophical systems such as Buddhism and Hinduism, will likely have more to contribute in the future as well. Even in `modern' measures such as the number of scientists and technologists, India is third in the world after the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. Many Indians have of course migrated to

the United States, thus contributing to a `brain drain' for India. The utilization of talent is

a serious issue for developing countries like India that is only now being addressed.

Significantly, as one of India's most prominent comparative educators, Professor

Suresh Shukla of Delhi University, has pointed out to us, India is firmly committed to three basic progressive goals: democracy, individuality, and the need to restructure

proper-ty and class relations. India's educational system is oriented around these goals. The ex-perience they have in attempting to implement such goals can be instructive for other

na-tions as well.

This is not a system oriented solely towards mechanical efficiency, however, as we were told by C.S. Nagaraju a leading educational sociologist in India. He strongly criticiz-ed Japanese and German criticiz-education, stating that these systems have traditionally had "an

over-emphasis on achieving excellence as defined by judging humans only by their

mechanical efficiency, a practice which led to World War II in both countries."

Perhaps Japan, America, and other nations could learn from the traditional Indian em-phasis on humanized, personalized learning as manifested in the guru-sishya system of ap-prentice learning (which, incidentally, has much resemblance to ie-seido and semPai-leohai relationships in Japan) . This area of apprenticeship as a model for education is one fully deserving our consideration as a research issue. Furthermore, the acceptance of diverse value systems is one of India's most positive contributions to world civilization. With a long history of relating education to understanding, tolerance, and compassion (Mahatma

Gandhi being only one in a long line of important educational philosophers) , India could

of-fer lessons to Japan in its quest for internationalization and joining the world. For now, though, Japan is regarded by many Indians as an ideal educational model.

Japan for them provides certain secrets of the power of education for social

transfor-mation, but a transformation which successfully melds tradition and modernity. The qualities of the Japanese experience that are especially valued by Indians are

pur-posefulness, egalitarianism, dedication, solidarity and hard work. The spirit of gambaru, of trying one's hardest, is of great interest to Indians. The development in Japan of an acute sense of responsibility towards the country, the home, and one's employer are also greatly admired. Finally, the pursuit of the independent course of development which Japan has

taken, rather than simply following American or other models, is something Indian

educators especially appreciate.

If Japan is to help developing nations like India, rather than simply treating these na-tions as markets for profits, the transfer of educational management technology, of the educational ideas behind Japan's successes, might be a good place to start. Helping to

resolve those issues of special concern to India and other developing nations iS, at the very

least, enlightened self-interest for Japan. The socio-economic development and political stability of developing countries is not only a duty and an obligation, but an imperative. And it means contributing people, not just money.

David B. Willis and Hiroyulei llatashima

In the search for policy alternatives, the experiences of Japanese education can help Indians and other developing nations see their own situation and their own options more clearly and with a broader perspective. We might state the promising areas of comparative cultural research between India and Japan, then, to be as follows:

1 . People at the Center of All Development (Learning for All, Not Just a Few)

2 . Teachers and Effective Teacher Training

3 . Elementary Schooling (Access, Quality, Effectiveness - Including the Provision

of Appropriate Preschool Education and Services)

4 . The Relation of Education and National Development: Rational Allocation of Resources Through Sophisticated Statistical Analyses

5 . Reaching Rural Areas: Provision of Equal and Appropriate Facilities

6 . Career Access: Education and Job Placement - Especially Vocational, mal and Adult Education (Including Lifelong Learning)

7 . Examinations and the Role of Credentialism

8 . The Values Crisis and Education

These are possible avenues for Japan's `soft aid' assistance for India and other developing nations. The key themes that run through all of these are educational and human capital development. These areas represent the best Japan has to offer, areas

where Japanese innovation as well as analytical and management capacity are indeed quali-ty endeavors. The lessons which can be transferred from Japan are especially appealing to

developing countries because of the philosophy that money is not the only solution to educational problems, that to be effective schooling needs not only money but certain techniques of human resource/ human capital manegement.

The key question is how Japanese ideas and experiences in education are responsible for the promotion and inculcation of those very qualities Indians and others value most about the Japanese experience again, purposefulness, egalitarianism, dedication,

educators and scholars of development interested in the role of Japanese

Japan's spectacular take-off from developing to super-developed country.

education in

A Research Note

As important contributors to this research, special thanks are due to Salim Firdouse, J. Rajasekaran, Lars Kjaerholm, R. Jayagopal, Malcolm Adiseshiah, C. S. Nagaraju, and C. Seshadri, who all kindly gave of their time and ideas concerning this topic. And an apology to them for being so slow in turning out this manuscript. For their information and for others, the paper is also available in Japanese, listed under the principal author's name in the bibliography.

The research for this paper was initially carried out during February and March of 1987 and was

sup-ported by a research grant from Soai University, Osaka, Japan. Later research was conducted using the sources listed below and on research visits to Tokyo, Japan, and Sussex, England, by the researchers.

Hiroyuki Hatashima, the second author, did much of the background study, including lengthy discussions

with co-researchers from India and various governmental and non-governrnental organizations while he

was a research fellow at the Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex in England.

During the initial period of the study, the principal author visited 17 universities, schools, think tanks, and other educational institutions in India, interviewed literally dozens of educators, and gave three major

presentations on possible lessons which Japanese education might have for India. Numerous comments

were received on these lectures. One of the clearest findings of this research trip was that there is much in-terest in the Japanese experience in countries like India, as well as an enormous reservoir of good will

towards Japan which the Japanese would do well to draw upon.

During this field study educational issues were also discussed with a wide range of individuals from the urban and rural poor, the intelligentsia, the middle class, and the elite. The main objective of the research was to obtain a preliminary sketch of the problems and prospects of Indian education today so as to deter-mine a more specific research agenda for the future, particularly in terms of the possible contributions of Japan as a model for developing societies.

The focus of the research and the prevailing themes for the interviews, then, were on three areas:

a) Indian education today - the status of elementary, secondary, tertiary, and other components of the

educational system of a developing country.

b ) Political and social problems affecting Indian education.

c) Future prospects for Indian educational development, especially the potential contributions Japanese educators could make to educational policy prescriptions.

An examination of alternative models and processes, notably in terms of the possible transfer from Japan of ideas from educational management and pedagogy, was an underlying theme of the research and

David B. JVillis and Hiroyuki Hatashima

was stated as such to those who were interviewed. Possible contributions which the experiences of Indian educators could make towards understanding other countries' educational systems were also explored, in-cluding those of other developing nations. Clearly, if the function of comparative education is to be regard-ed as truly enlightening (real `learning' rather than mere `instruction') then our task should be seen at the very least as a bilateral process, a two-way street.

A Note on Comparative Education in India

As Professor Krishna Kumar wrote to us in April 1987, comparative education in India is regarded (even by comparative educators) as a minor development, despite the enormous possibility of comparative research within India. There is a Society, the Comparative Education Society of India, which promotes comparative research, publishes a newsletter, and holds a conference every other year. The Society may be reached at the following address: Professor D. A. Dabholkar, President, CESI, 8 Kshipra Society, Karvenagar, Pune, 411052, Maharashtra, India. ``Beyond these routine things, however, there is little."

The most useful research to date is a seminal article in 1983 written for the ComParative Education Review by Professor Suresh Shukla, Head of the Department of EduÅëation of Delhi University, in which he gave his

overview of Indian comparative research. Dr. Shukla is regarded as the dean of Indian comparative educators. It should be mentioned however that he has somewhat different views regarding the role of

Japan in India's educational development. In a personal correspondence of March 2, 1987, Professor Shukla stated as follows:

``Your thought that Japan's export of its human relations `management' or the management of

cultural networks represdnts a new possibility for the immediate future is interesting. However as in

my perception the Japanese development is essentially from topldownwards it would reinforce tional authorities and structure.

Such a development in to-day's under-developed countries may be both difficult and perhaps not

desirable. The ideas of democracy and individuality and the need to re-structure property and class relations which are seen as progressive goals in our societies appear to me to be too important to sacrifice.''

These are important thoughts whic

prepare to enter the 21st Century.

h pertain to Japanese and American, as well as Indian, education as we

Select Bibliography

Bibliographic Note: The depth of Indian educational research is great and has wide-ranging implications. Despite the fact that much of this research is in English, however, little of it has been appreciated outside the Subcontinent. The rich findings of Japanese educational scholarship should also be noted here. They have also been neglected by researchers outside of Japan, although here, of course, the linguistic barrier of the Japanese language is a formidable obstacle.

Adiseshiah, M. S. Adult Education Faces Inequalities. Madras: Sangam Publishers, 1981.

York: Praeger, 1975.

Anderson, Lascelles and Windham, Douglas. Education and Development. Lexington: Lexington Books, 1982. Arnove, Robert F., ed. PhilanthroPy and Cultural ImPen'alism. Bloomington: Indiana University press, 1982. Arora, K. L. Education in the Emerging Indinn Eiociety. Ludhiana: Parkash Publishers, 1986.

All India Democratic Students' Organisation. The New National Edzacation Policy - A Challenge Against

Education. Calcutta: All India Democratic Students' Organisation, 1986.

Altbach, Philip G. and Kelly, Gail P. Education and Colonialism. New York: Longman, 1978.

Altbach, Philip G. and Kelly, Gail P. New APProaches to ComParative Education. Chicago: University of Chicago press, 1986.

Bhanote, S. N. ``Development of India and Japan: The Role of Education,'' Journal of Indian Education,

November 1985, pp.3-11.

Bhatia, Kamala and Bhatia B. D. Theo2), and PrinciPies of Education. Delhi: Doaba House, 1[ 86.

Biswas, A. and Aggarwal, J. C. ComParative Educaton. New Delhi: Arya Book Depot, 1972.

Brandt, Willy, et al. North-South: A llProgramme for Surz,ival. London: Pan Books, 1980.

Camoy, Martin. Education as Cultural ImPerialism. New York: David McKay, 1974. Chaube, S. P. ComParative Education. Agra: Ram Prasad and Sons, 1986.

Collins, Randal. The Credential Sociely. New York: Academic Press, 1979.

Coombs, Philip H. The World Crisis in Education - The Viewfrom the Eighties. New York: Oxford, 1985.

Coombs, P. H. and Manzoor, A. Attacking Rural Poverty - How Non-Formal Education Can HelP.

Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 1974.

Cummings, William K., et al. Ed"cational Policies in Crisis. New York: Praeger, 1986.

Cummings, William K; Tomoda, Yasumasa; and Gopinathan, S. The Revival of Values Education in East and West. London: Pergamon, 1988.

Cummings, William K. Education and Equalitv in JaPan. Princeton: 1980.

Dabholkar, Devdatta. ``Education in India: A Perspective on Policy Perspectives," Perspectives in tion, April 1986, pp.67-76.

Dahama, O. P. and Bhatnagar, O. P. Education and Communica tionforDeveloPment. New Delhi: Oxford, 1985. De Rebello, D. M. "Do Schools Make a Difference in India?,'' Socini Change, June-September 1986, pp.57-67. Desai, Uday. ``Colonial Legacy, Illiteracy and Education in India," Education and Soct'ety, Volumes 3/2-4/1,

1986, pp.52-61.

Dore, R. P. The DiPloma Disease: Education, Ot"ili ication and DeveloPment. London: George Allen &

win, 1976.

Dore, Ronald P. and Sako, Mari. How the faPanese Learn to Work. London: Routledge, 1989. Duke, Benjamin. The JaPanese School. New York: Praeger, 1986.

Dumont, Louis. Homo Hierarchicus. London: Paladin, 1970.

Fagerlind, Ingemar and Saha, Lawrence. Education and National Development: A ComParative PersPective. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1983.

Freire, Paulo. CulturalActionfor Freedom. Middlesex: Penguin, 1977.

Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the OPPressed. Middlesex: Penguin, 1972. Garret, Roger, ed. Education and DeveloPtnent. London: Croon Helm, 1984.

Giddens, Anthony. The Consequences ofModernity. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990.

Geertz, Clifford. Local Knowledge. New York: Basic Books, 1983.

Gokak, Vinayak Krishna. Indian Higher Education. Bangalore: IBH Prakashana, 1981.

llavid B. Willis and Hiroyuki Hatashima

Hans, Nicholas. ComParative Education. New Delhi: Universal Book Stall, 1986.

Harrison, David. The Sociology ofModerni2ation and DeveloPment. London: Unwin Hyman, 1988.

Harrison, Paul. Inside the Third World. Middlesex: Penguin, 1981.

Horowitz, Irving Louis. Three VVorlds ofDeveloPment. New York: Oxford, 1973.

Hulme, David and Turner, Mark. Sociology and DeveloPment. New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1990.

Husen, Torsten. The Learning Eibciety Revisited. Oxford: Pergamon, 1986. Illich, Ivan. Shadow Worle. Boston: Marion Boyars, 1981.

Jayagopal, R. Adult Learning - A Psycho-Social Analysis in the Indian Context. Madras: University of

Madras, 1985.

Joshi, V. and Menon, G. "Research on Women's Education in India: A Review," PersPectives in Education,

April 1986, pp.77-98.

Kabir, Humayun. Indtan PhilosoPhy ofEducation. Bombay: Asia Publishing House, 1961.

Khanna, S. D. et al. Fundumentals of Education. Delhi: Doaba House, 1985. Kochhar, S. K. Pivotal Issues in Indinn Education. New Delhi: Sterling, 1981.

Leestma, Robert and Walberg, Herbert J. JaPanese Educational Productivity. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1992.

Leestma, Robert and Walberg, Herbert J. JaPanese Education Toclay. Washington: U.S. Government, 1987. Little, Angela. "Education and Development: Macro Relationships and Micro Cultures,'' Paper for 25th

Jubilee of the Institute of Development Studies, Sussex, U.K., 1991.

Mannari, Hiroshi and Befu, Harumi, eds. The Challenge ofJaPan 's Internationali2ation. Tokyo: Kodansha,

1983.

Mehendiratta, Pradeep R. University Administration in India and the USA. New Delhi: Oxford, 1984. Ministry of Human Resource Development. NationaiPolicy on Education - 1986. New Delhi: Government

of India, 1986.

Mohanty, J. Indlan Education in the Emerging Society. New Delhi: Sterling, 1986.

Mukerji, S. N. Education in Indin - Today and Tomorrow. Vadodara: Acharya Book Depot, 1976. Murakami, Yasusuke and Kosai, Yutaka, eds. JaPan in the Global Community. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 1986.

Myrdal, Gunnar. Asian Drama. New York: Pantheon, 1968.

Myrdal, Gunnar. The Challenge of World Povemp. New York: Vintage, 1970.

Nagaraju, C. S. "Primary Education in the Seventies: An Analysis." Indian Educational Review, January 1986, pp.129-137.

Nagaraju, C. S. "Southern Regional Seminar on Planning and Management Aspects of the New Education Policy." Bangalore: Institute for Social and Economic Change, 1985.

National Council of Educational Research and Training. National Curn-culum for Pn'mary and Secondary Education. New Delhi: NCERT, 1985.

National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration. NIEPA - An Introduction. New Delhi:

NIEPA, 1987.

Pareek, Udai. Education and Rural Development in Asia. New Delhi: Oxford, 1982.

Patil, V. T. and Patil, B. C. Problems in Indian Education. New Delhi: Oxford, 1982.

Pillai, J. K. and Mohan, S. Why Graduates Choose to Teach - A Survey. Madurai: Madurai Kamaraj University, 1985.

Psacharopoulos, George. "Education and Development: A Review," Research Observer, 3, no.1 (January 1988), pp.99-116.

Rohlen, Thomas B. fapan's H7igh Schools. Berkeley: University of California, 1983.

Rudolph, Lloyd and Rudolph, Susanne. The Modernity of Tradition. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1967.

Rudolph, Susanne and Rudolph, Lloyd. Education and Politics in India - Stndies in Organization, Society

and Policy. Bombay: Oxford, 1972.

Ruhela, S. P., ed. Socinl Determinants of Educability in India. New Delhi: Jain Brothers, 1969. Rnhela, S. P., ed. Human Values and Education. New Delhi: Sterling, 1986.

Safaya, R. N. Current Problems in lndian Education. Jullundur: Dhanpat Rai & Sons, 1986.

Seshadri, C. APEID OPerational Seminar on ImProving Access to Education of Disadvantaged GrouPs.

.

Mysore: Unpublished Ms., 1987.

Seshadri, C. "The Concept of Moral Education: Indian and Western - A Comparative Study,'' parative Education, Volume 17, No.3, 1981.

Seshadri, C. "Teacher Education - The Continuing Debate,'' Journal oflndinn Education, November 1986, pp.3-11.

Shamsuddin, ``The Role of Teachers in a Changing Society," lournal of lndinn Education, November 1986,

pp.49-51.

Sharma, R. N. and Sharma, R. K. Sociology of Education. Bombay: Media Promoters & Publishers, 1985.

Shields, James J., ed. JaPanese Schooling. University Park: Penn State Press, 1989.

Shinji, P. M. Rurai Youth: Education, OccuPation and Social Outlook. New Delhi: Abhinav Publishers, 1980. Shukla, P. D. Administration of Education in India. New Delhi: Vikas, 1983.

Sodhi, T. S. A Textboole of ComParative Education. New Delhi: Vikas, 1{ 83.

Stevenson, Harold; Azuma, Hiroshi and Hakuta, Kenji. Child DeveloPment and Education in JaPan. New York: Freeman, 1986.

Streeten, Paul. ``Global Governance for Human Development," Paper for 25th Jubilee of the Institute for

Development Studies, Sussex, U.K., 1991.

Suri, G. K.; Prasad, Rajendra, and Barman, A. K., "Survey Report - India,'' in Muta, Hiromitsu, ed. Educated UnemPloyed in As•i , Asian Productivity Organization, Tokyo, 1990.

Thapan, Meenakshi. ``Aspects of Ritual in a School in South India,'' Contributions to Indian Sociology,

December 1986, pp.199-220.

Thomas, T. M.Indian Educational Reforms in Cultural PersPective. New Delhi: S. Chand & Co., 1970. UNESCO. "Educational Research in Asia,'' Education in Asin. Number 6. September 1974, pp.9-12. Venkatasubramanian, K. Education and Economic DeveloPment in India - Tamil Nadu - A Case Study Delhi: Frank Bros. & Co., 1980.

White, Merry. The JaPanese Educational Challenge. New York: Free Press, 1987.

Willis, David. Indo No Kiyoiku to Nihon E No Teiigen - Nihon Kiyoiku No Hatten No Tame Ni, Dona Goken Ga Dekiru ka? (Indian Education and Suggestions from Japan - What Contributions Can Japan Make for the Development of Education?). Trans. by Tadashi Maeda. In Sekai No Ki oiku, Nihon No Kiyoileu ( VVorld Education - faPanese Education) , Haruhide Mori, Ed. Kyoto: Yamaguchi Shoten. World Bank. JVorld DeveloPment RePort 1990. Washington, D. C.: World Bank, 1990.

Worsley, Peter. The Three vaorlds - Culture & W(orld DeveloPment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press,