*Corresponding author: gr0346xk@ed.ritsumei.ac.jp

A Qualitative Investigation into Definitions of Advertising in

China: The Short Video Perspective

Xintao YU

*, Takashi NATORI

Graduate School of Technology Management. Ritsumeikan University Osaka Ibaraki Campus 2-150 Iwakura-cho, Ibaraki, Osaka, 567-8570 JAPAN

Abstract

With the rapid development of AI technology and 5G in China, the country’s advertising industry has changed significantly, perhaps even more than in other countries. This paper suggests that the magnitude of change means traditional definitions of advertising are no longer appropriate. Specifically, it considers such definitions of advertising with Chinese characteristics in the context of short video viewers by using grounded theory to code interviews with 14 Chinese netizens. In addition to providing a new definition of advertising for Chinese advertising, the paper forecasts advertising in the future for practitioners and academics in other countries.

Keywords: definition of advertising, grounded theory, Chinese characteristics, short vide

1. Introduction

Modern advertising can be said to have begun early in the 20th century, when Albert Lasker, known as the “father of modern advertising,” defined commercial advertising as “salesmanship in print.” Soon afterward, in 1923, Daniel Starch introduced “salesmanship in print.” Although many definitions of advertising have emerged and coexisted, Richards et al. (2002) recognized that starting at a common point was essential for sharing understanding and developing future definitions of both advertising and related concepts[34]. Dahlen et al. (2016) and Kerr (2020) both discussed the drastic need to propagate a new definition of advertising due to advertising changing with the shifts in popular mediums; that is, the advertising evolved as it moved from print to radio to television to computers to smartphone[12][18].

Now, at the beginning of the 5G era, the new advertising paradigm should be defined. AI and big-data technology enable advertising to innovate. Lee et al. (2019) observed AI-assisted innovation in advertising – AI can not only intelligently recommend audiences something they would like to watch but also integrate other applications to analyze what you want to know[23]. Advertising has changed––this is self-evident; nonetheless, according to an analysis of more than 300 articles published between 2008 and 2018 in 10 leading journals, there has been little discussion of a new definition of advertising (Liu-Thompkins 2019). According to Chang (2017), dominating advertising researches are the positivist paradigm, message effects, and consumer psychology[7].

The China Internet Network Information Center (2019) indicated that China’s internet population had reached 854 million by June 2019 and that 99.1% of those users accessed the Internet by phone. Short video entered the top three most-consumed media formats, with users of short video applications reaching about 758 million, 88.8% of netizens[8]. New advertising formats are approaching

these users, but there is no appropriate definition to interpret this phenomenon yet.

Therefore, for this study, we considered China’s mainstream short video applications: TikTok, WeSee, WeChat Moments, Quick Worker, Sina Weibo, Redbook, and Bilibili. Given these are all similar in function and content, we chose TikTok, one of the most influential short video applications in China, as a representative research object. TikTok is a video-sharing social networking service owned by ByteDance, a Beijing-based internet technology company founded in 2012 by Zhang Yiming, and has become very popular among teenagers in recent years. Yurieff, writing for CNN (2018), indicated that the Chinese short-form video application, TikTok, had gained global momentum, defeating other popular apps, including Youtube, Facebook, and Instagram, in overall downloads in 2018[43].

TikTok became a buzz application because it not only used a perfect monetary reward mechanism but also understood consumer needs accurately. Tiktok considered people who live in a busy society with no time for or interest in long videos, words, or pictures, but who need to access information or relax. Meanwhile, the monetary reward mechanism also stimulates people who create content for the platform.

The application’s evaluation index calculates overall “likes,” “comments,” and “reposts” before distributing rewards. Meanwhile, other corporations commission TikTok influencers make short videos to promote their brand. However, before users become candidates for commissions or rewards from TikTok, they need to attract fans. This led to some regulatory problems, with Jane Wakefield reporting for BBC (2020) that “a stunt being shared on viral video platform TikTok… caused serious injury among teenagers in the UK and US[40].” Additionally, Zhang et al. (2019) suggested that short video formats, like TikTok, can result in addiction[44].

If this course is not corrected, history informs us that there are likely to be many moral, legislative, or educational consequences.

2.

Literature Review

The Lessons of History

It is said that history repeats itself. For example, Steven (2019) conducted a historical analysis of the children’s magazine Jack and Jill, published in the World War II period[38]. Jack and Jill was known for having no advertisements; however, it contained content concerning the U.S. Treasury's War Bonds and Stamps Drive and the “United We Stand” campaign. These were regarded as patriotism campaigns rather than any kind of advertisement. Because they did not directly earn money, Americans believed that such content was not advertising. This kind of deep cognitive advertising is prevalent on the Internet nowadays.

An example of this subtle advertising is Steven identifying word puzzle games including words like “bond,” “tank,” “bomb,” “guns,” and “jeep” in the February 1943 issue of Jack and Jill. Another example is a drawing by a young reader depicting a bald eagle with its wings spread with a hefty tag hanging from its neck reading “war bonds,” and the hand-written words “keep him flying” underneath. These have forceful semantic implications, which could be regarded as a persuasive strategy. Rather than commerce-oriented keywords, they are military keywords, enabling comparison with the vlog format prevalent, in contrast to direct persuasive advertising. Steven claimed that, ironically, the US Treasury “earned” enough money from this campaign to purchase more than 90,000 jeeps, 11,700 parachutes, and 2,900 planes––US children had bought more than $1 billion worth of stamps and bonds by 1944.

However, revision of the definition of advertising should not be purely semantic. Laczniak (2016) recognized that advertising formats would become very diverse and different in the near future[21]. Rust and Oliver predicted “the death of advertising” in 1994, and Richard et al. (2002) noted that if definitions of advertising are too narrow, the discipline may shrink[35][34]. Campbell et al. (2014) suggested that “greater definitional clarity enables practitioners—both on the brand and agency sides—to streamline processes, initiate clearer strategy, and respond to emerging ethical concerns[6].” Kerr and Richards (2020) believed it crucial that definitions of advertising match changes in advertising practice[18]. However, with the continued development of AI technology and big data, Chinese teenagers hardly watch TV, preferring forms of self-media self-media managed by individuals to share their talent, story, or skill. Of China’s 854 million netizens, 45.5% are under 30 years old (China Internet Network Information Center 2019). At almost 400 million people, this audience is bigger than the total US population. Thus, a new definition of advertising is required to understand this market.

Kerr and Richards (2020) also demanded a uniform definition crossing national borders to offer better

multinational communication bridging geographically disperse advertising entities; for now, though, previous research into the definition of advertising is irrelevant for contemporary Chinese advertising[18].

The Contemporary Short Video Format

Influencers design a series of short videos to attract other users; these storylines are called vlogs, a term derived from the word “blog.” Hoek et al. (2020) showed that vlogs had become an excellent marketing tool for reaching teenagers.

Creators use the “#Topic” function to include “#keyword(s)” when uploading their vlogs; for example, “I am going to buy some new #KFC food sets.” Such vlogs will appear when other users search “KFC” in the application. This happens in many different fields––other topics include #LOL (a game’s name), #travel in Japan, #IgotanewiPhone. This phenomenon serves as free secondary brand communication for those brands, products, or travel places and exists in the form of, for example, “evaluation of new smartphones or computers,” “evaluation of cars,” “office life,” “school life,” “food recommendation at some city,” “America life,” “Japanese life,” “UK life,” “Russia life,” “the news,” and “Steam game recommendations.”

We have summarized the conditions of some representative forms, which are similar to mainstream forms:

1. In the storyline series, the protagonist is usually a man who suddenly meets a girl. They go out to have dinner, hang out, do various daily life activities and, finally, fall in love. This kind of storyline attracts other users’ curiosity. Most of these accounts sell commodities, such as clothing, when they get enough followers.

2. In the foreign marriage series, users show daily life in different countries, exploring cultural differences, such as the delicious food from the two countries, which they eat and evaluate. They sell commodities, such as baby products, when they attract enough followers.

3. In the study abroad series, users mainly show cultural differences in daily life. Sometimes they make mistake propaganda deliberately to attract followers, such as only showing odd phenomena from the country. They mostly sell foreign products or online education products.

4. In the e-sport series, users play popular games and produce clips, inserting a caption or narration as part of the short video. They sell game coupons, gaming computer products, and peripheral products.

5. In the clipped film series, users edit recent popular mainstream films into short videos, including captions, which help people understand the film more clearly due to there are many accents in China. Generally, these are business-to-business companies using their company name or brand name as the username; users will click “like” if they like the film, leading more users to learn about it.

6. In the breaking news series, national or local governments, TV stations, newspaper offices produce content that is generally not selling anything. Still, in the

case of a severe problem, such as a natural disaster, they might help people in trouble to sell things. For example, during COVID-19, they helped corporations sell products to support them in fighting the recession. All series types except this one accept customized advertising promotion, which cost between 200 and 3,000 dollars to shoot. The one-time charge by an account with 100,000 followers is 200 to 700 dollars.

7. In the eating show series, different foods, both Oriental and Western, are consumed in front of a camera. This became popular in South Korea in 2010; since then, it has become a worldwide trend. Generally, restaurant owners and sometimes food companies commission users to eat their food and interpret it.

8. In the skill-sharing series, creators provide solutions for followers who want to learn a skill to improve their lives or solve problems at their job. Creators might make money by selling lessons, books, or school supplies.

This is not an exhaustive list of series types; other examples include “the success theory or business series,” “the cooking series,” “animals vlog series,” “the children series,” and “the entertainment series.”

Kerr and Richards (2020) suggested that advertising describes a word being ingrained in our minds, meaning it is necessary to reflect on advertising during times of new advertising phenomena, as this can enable the classification of a new advertising format[18].

To investigate this and propose a new definition of advertising for short video advertising in China, we developed the following research question:

RQ: How can advertising with Chinese characteristics be defined for the short video format?

From an academic perspective, this paper contributes to the continued research into new advertising formats for

the 5G era. From a practitioner’s perspective, the paper offers suggestions for the development of new advertising formats.

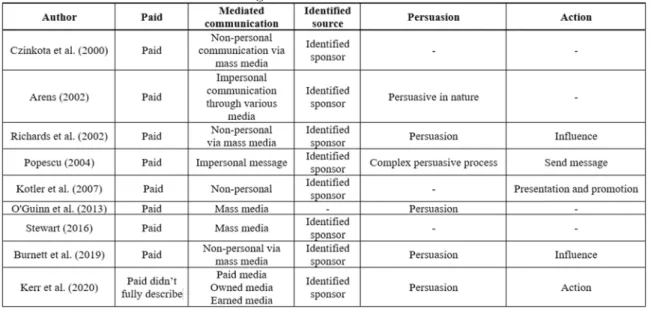

Definitions of Advertising Since 2000

This study concentrates on the last two decades of research, especially research that has used computer technology as a tool. Specifically, we investigated different constructs described by Kerr and Richards (2020)[18]. Table 1 organizes these constructs according to five criteria: (1) paid/not paid, (2) mediated communication, (3) identified source, (4) persuasion, and (5) action.

It can be said that there are six types of advertising formats: product advertising, institutional advertising, informative advertising, persuasive advertising, reminder advertising, and comparison advertising. Kerr and Richards (2020) showed that these share three forms of mediated communication with viewers: (1) paid media, (2) owned press, (3) earned media. DiStaso et al. (2015) described paid media as traditional advertisements for print, radio, and television mediums[13]. Owned media describes the company’s website, public accounts on major platforms, and blogs. Earned media results from public relations or effects such as word-of-mouth.

Czinkota et al. (2000) showed that “non-personal communication that is paid for by an identified sponsor, and involves either mass communication via newspapers, magazines, radio, television and other media (e.g., billboards, bus stop signage) or direct-to-consumer communication via direct mail communication with consumers[10].”

Arens (2002) showed that “a form of structured and impersonal communication, composed from information, usually persuasive in nature, regarding the products, in the broad sense, paid by an identifiable sponsor and transmitted through various media persuade consumers[3].”

Richards et al. (2002) described advertising as including five elements: (1) paid, (2) non-personal, (3) identified sponsor, (4) mass media, (5) persuasion and influence. Then, they modified these elements into (1) paid, (2) mediated, (3) identifiable source, (4) persuasion, and (5) action[34]. The “mediated” element describes that which is “conveyed to an audience through print, electronics, or any method other than direct person-to-person contact.” According to Popescu (2004), advertising is communication technique that involves running a complex persuasive process, for whose realizations are used many specific tools, able to cause psychological pressure on the concerned public[33]. The initiator of the advertising communication actions is the sponsor, who, to achieve communication objectives, wants to send an impersonal message to a well-defined audience regarding the enterprise, its products, or services. Elsewhere, Kotler et al. (2007) recognized that “advertising is any paid form of non-personal presentation and promotion of ideas, goods, or service by an identified sponsor[19].”

Advertising in the Internet Era

In 2008, Arens et al. recognized that the Internet could serve as a communication channel but also as a transaction and distribution channel[1]. Cross (2011), media on the Internet and mobile phone applications are a type of mass media often called digital media[9], while Dahlen and Rosengren (2016) agreed that, due to the increased use of digital media, revisions to the definition of advertising had not gone far enough and more change was necessary[12].

O’Guinn et al. (2013) considered advertising as “a paid, mass-media attempt to persuade consumers[27].” Consequently, Stewart (2016) discussed whether or not the element "paid" should be removed due to being vague in the current circumstances[39]. Moriarty et al. (2019) described advertising as “paid non-personal communication from an identified sponsor using mass media to persuade or influence an audience[36].”

In addition to their five elements of advertising Kerr and Richards (2020) suggested a new definition of advertising: “Advertising is paid, owned, and earned mediated communication, activated by an identifiable brand and intent on persuading the consumer to make some cognitive, affective or behavioral change, now or in the future[18].”

Over the first 20 years of the 21st century, definitions of traditional advertising have involved characteristics such as “paid,” “non-personal,” and “identifiable sponsor.” However, many studies conducted research using practitioners and academics rather than general consumers.

3.

Research Method

This study analyzes the collected data using the grounded theory developed by Glaser in 1967. Glaser (2001) indicated that grounded theory combines positivism with theory, abstraction, and concreteness, providing a whole set of methods and steps to construct

a theory from original data[14]. The grounded theory emphasizes the organic, interactive process of sampling interviews and data analysis; the two links promote each other and are inseparable. Therefore, this method is appropriate for revising outdated definitions of advertising.

According to Brotheridge (2002), a grounded-theory approach includes: (1) in-depth analysis of data, development of concepts from data, and hierarchical logging of data; (2) constant comparison of data with concepts and systematic questioning related to conceptual generative theory; (3) development of theoretical concepts and establishment of connections between concepts; (4) theoretical sampling and systematic coding of data; (5) construction of theories and attempt to understand the density, variation, and level of conformity of theoretical concepts[5]. Using the grounded theory approach, this study constructed a theoretical framework for a new definition of advertising through open coding, spindle coding, and selective coding of the original interview documents.

Open coding

The purpose of open coding is phenomenon induction, concept definition, and discovery (also known as data collection). Patton (1990) suggested that this process requires researchers to remain open and neutral with “theoretical touch,” to comprehensively capture key information points in the data, and then to gradually abstract and name typical contents[31]. Category names can be derived by the researchers or borrowed from existing research. The relevant dimensions and categories are not selected by the researcher before beginning the research, but “emerge” objectively through the coding process.

Axial coding

In axial coding, the main categories found through open coding are developed in more depth. Using axial coding for the discovery phase creates internal links between different categories. According to the relationship between different open coding categories, there were six main categories and 479 labels.

Selective coding

In selective coding, the relationship between the main categories is analyzed, and its related structure is expressed, allowing the development of a new theoretical framework.

Selecting Interviewees

According to the China Internet Network Information Center (2019), among Chinese Netizens, males constitute 52.4% and females 47.6%; children under ten years old constitute 4.0%, 10–19-year-olds constitute 16.9%, 20–29-year-olds constitute 24.6%; 30– 39-year-olds constitute 23.7%, 40–49-year-olds constitute 17.3%, 50–59-year-olds constitute 6.7%, and adults over 60 years old constitute 6.9%; users educated at a primary school level or lower constitute 18.0%; users

educated at a junior school level constitute 38.1%, users educated at a senior or technical school level constitute 23.8%, users educated at a technical college level constitute 10.5%, users educated at a university level or higher constitute 9.7%; students constitute 26.0% and freelancers constitute 20.0% and other[8]. Botev et al. (2017) described stratified sampling as a method of sampling from a population which allows partitioning into subpopulations according to statistics. This method is generally used when a population is not a homogeneous group[4]. In statistical surveys, when subpopulations within an overall population vary, it can be advantageous to sample each subpopulation (stratum) independently. Stratification is the process of dividing members of the population into homogeneous subgroups before sampling. The layers should define partitions. That is, the partitions should be collectively exhaustive and mutually exclusive, with every element of the population assigned to only one stratum. Then, simple random sampling or systematic sampling can be applied within each layer. The objective is to improve the precision of the sample by reducing sampling error. This can produce a weighted mean that is less variable than the arithmetic mean of a simple random sample of the population. Accordingly, we used this method to choose our interviewees.

Dimensions of the Definition

This study investigated definitions of advertising according to the constructs developed by Kerr and Richards (2020)[18].

Questionnaire Design

While Kerr and Richards (2020) used practitioners and academics as research subjects, we considered that advertising for general consumers needs to be clearly understood[18]. Thus, to create a new questionnaire for a general audience before collecting data, we used the definition of advertising as “paid, owned, and earned mediated communication, activated by an identifiable brand and intent on persuading the consumer to make some cognitive, affective or behavioral change, now or in the future” to create a pilot test to trial with nine Chinese users of short video applications.

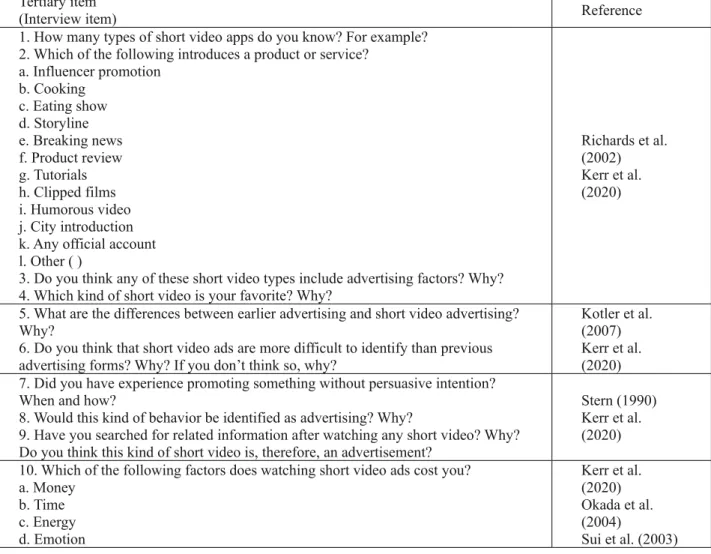

For each interview, we explained our research objective and its theoretical grounds, ensured each interviewee understood the essential conditions, then showed short videos and asked the interviewee if they considered whether the videos included advertising implications. This enabled the development of the questionnaire presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Questionnaire Tertiary item

(Interview item) Reference

1. How many types of short video apps do you know? For example? 2. Which of the following introduces a product or service?

a. Influencer promotion b. Cooking c. Eating show d. Storyline e. Breaking news f. Product review g. Tutorials h. Clipped films i. Humorous video j. City introduction k. Any official account l. Other ( )

3. Do you think any of these short video types include advertising factors? Why? 4. Which kind of short video is your favorite? Why?

Richards et al. (2002) Kerr et al. (2020)

5. What are the differences between earlier advertising and short video advertising? Why?

6. Do you think that short video ads are more difficult to identify than previous advertising forms? Why? If you don’t think so, why?

Kotler et al. (2007) Kerr et al. (2020) 7. Did you have experience promoting something without persuasive intention?

When and how?

8. Would this kind of behavior be identified as advertising? Why?

9. Have you searched for related information after watching any short video? Why? Do you think this kind of short video is, therefore, an advertisement?

Stern (1990) Kerr et al. (2020) 10. Which of the following factors does watching short video ads cost you?

a. Money b. Time c. Energy d. Emotion Kerr et al. (2020) Okada et al. (2004) Sui et al. (2003)

e. Other ( )

11. Do you think short video ads have an influence on your life now or will in the future?

12. Which of the following kinds of changes might happen or have already happened in your life after watching short video ads?

a. Attention b. Interest c. Search d. Asking e. Buying f. Sharing g. Other ( ) Wei et al. (2012) Kerr et al. (2020)

13. Could you tell me what your definition of short video advertising would be? Kerr et al. (2020)

4. Results

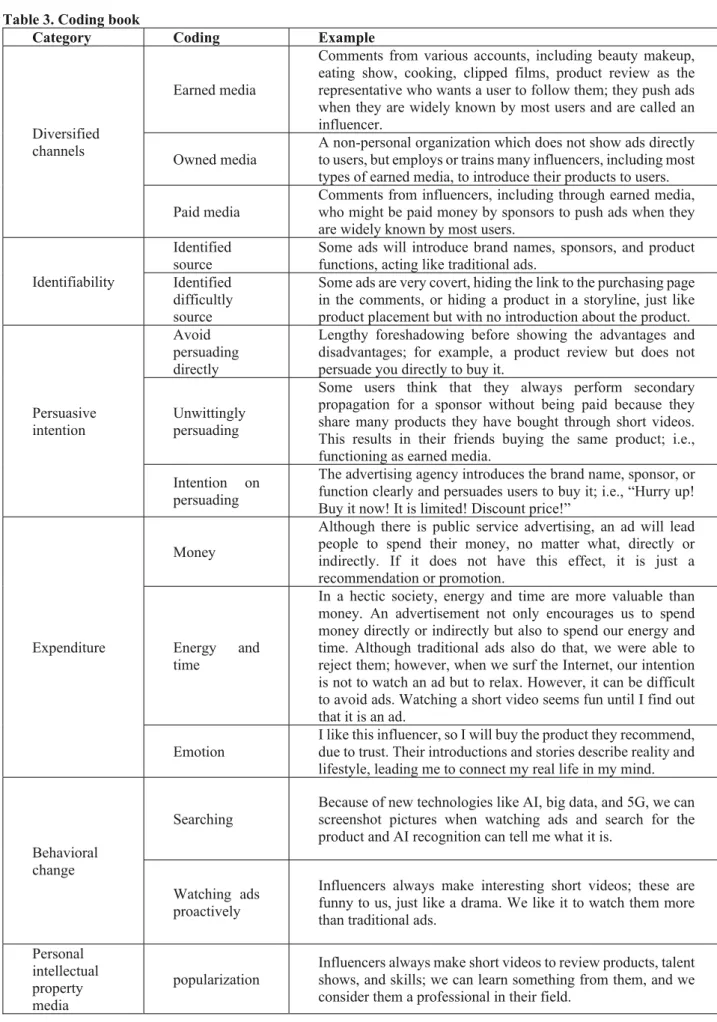

We interviewed 14 consumers in China; Table 3 shows coding from these interviews. Interviewees felt that advertising included various channels (85% agreement), that paid media is mainstream (78% agreement). Owned media was mentioned by 71% of interviewees, and 57% of interviewees said that earned media includes product reviews. Interviewees felt that the product in short video ads could be identified (93% agreement), while 64% of interviewees suggested some ads are difficult to identify. There was broad agreement that current advertising mostly avoids persuading users directly (86% agreement), while 71% of interviewees considered many short videos to not feature intentional persuading. The persuading in short video ads could be considered self-aware (86% agreement). Almost 93% of interviewees considered time, energy, and emotion to be most critical. Interestingly, to search, AI graphic recognition technology could recognize many pictures from users. Interviewees would be more curious without persuading (86% agreement), while 43% of interviewees like to watch short video ads. There was broad agreement (86%) that short videos allow everyone the chance to be an influencer.

For 20-year-old interviewees still in university or college, it was challenging to identify elements of an ad. However, those who had graduated from university or college and were around 30 years old found it easier. Unfortunately, we were unable to interview older people, teenagers, or people under the age of ten, necessitating further investigation.

Diversified Channels

Interviewees always have watched recommendations from influencers, which might have been paid for by sponsors to push a product using their influence. Influencers are in various fields: some review products, others feature in categories such as cooking, eating show, storytelling, funny video, food trail, and skill sharing.

Interviewees mentioned that influencers “will not push products before they are known to a lot of users, but they always make something eye-catching.” According to 71% of interviewees, owned media always employs handsome boys and beautiful girls and trains them to be influencers before pushing their products when they generate buzz. These influencers are mainly present in the skill-sharing category, as well as being present in the mainstream storytelling and product reviews of official accounts. According to 57% of interviewees, earned media has always used product reviews to introduce the advantages and disadvantages of products through professional data analysis, such as data from a quality inspection report from authority.

Identifiability of Source

Interviewees felt that the products in short video ads could be identified (93% agreement). For example, “they will [include] information [about the] brand or sponsor in their profile.” Furthermore, placing the product in front of the camera provides a direct advertising message––to allow followers to see the logo, it is more straightforward to set the shot in front of a goods shelf. Interviewees thought that the products in short video ads were difficult to identify (64% agreement). Some ads are very covert, hiding a link to a purchasing page in the comments, or hiding the product in a storyline; this is just like product placement but with no introduction of the product. One interviewee commented that “they have always made stories to stimulate me to connect with my real life in my mind; thus, I am not quickly aware this is an ad.”

Moreover, sometimes, users play the part of secondary propagation without perceiving it. For example, “I feel this is so interesting that I will share it with my friends. Then, they might buy something through my link. But I don’t receive any benefit, so it just is a free ad for the sponsor.” Finally, some people considered all exposure to be advertising.

Table 3. Coding book

Category Coding Example

Diversified channels

Earned media

Comments from various accounts, including beauty makeup, eating show, cooking, clipped films, product review as the representative who wants a user to follow them; they push ads when they are widely known by most users and are called an influencer.

Owned media A non-personal organization which does not show ads directly to users, but employs or trains many influencers, including most types of earned media, to introduce their products to users. Paid media

Comments from influencers, including through earned media, who might be paid money by sponsors to push ads when they are widely known by most users.

Identifiability

Identified

source Some ads will introduce brand names, sponsors, and product functions, acting like traditional ads. Identified

difficultly source

Some ads are very covert, hiding the link to the purchasing page in the comments, or hiding a product in a storyline, just like product placement but with no introduction about the product.

Persuasive intention

Avoid persuading directly

Lengthy foreshadowing before showing the advantages and disadvantages; for example, a product review but does not persuade you directly to buy it.

Unwittingly persuading

Some users think that they always perform secondary propagation for a sponsor without being paid because they share many products they have bought through short videos. This results in their friends buying the same product; i.e., functioning as earned media.

Intention on persuading

The advertising agency introduces the brand name, sponsor, or function clearly and persuades users to buy it; i.e., “Hurry up! Buy it now! It is limited! Discount price!”

Expenditure

Money

Although there is public service advertising, an ad will lead people to spend their money, no matter what, directly or indirectly. If it does not have this effect, it is just a recommendation or promotion.

Energy and time

In a hectic society, energy and time are more valuable than money. An advertisement not only encourages us to spend money directly or indirectly but also to spend our energy and time. Although traditional ads also do that, we were able to reject them; however, when we surf the Internet, our intention is not to watch an ad but to relax. However, it can be difficult to avoid ads. Watching a short video seems fun until I find out that it is an ad.

Emotion I like this influencer, so I will buy the product they recommend, due to trust. Their introductions and stories describe reality and lifestyle, leading me to connect my real life in my mind.

Behavioral change

Searching Because of new technologies like AI, big data, and 5G, we can screenshot pictures when watching ads and search for the product and AI recognition can tell me what it is.

Watching ads proactively

Influencers always make interesting short videos; these are funny to us, just like a drama. We like it to watch them more than traditional ads.

Personal intellectual property media

popularization

Influencers always make short videos to review products, talent shows, and skills; we can learn something from them, and we consider them a professional in their field.

Persuasive Intention

Current mostly avoid persuading users directly (86% agreement), with almost 71% of interviewees expressing that many short videos do not intentionally persuade. However, they do not know whether influencers persuade unwittingly or through product placement; nonetheless, this is also a type of ad. Because AI graphic recognition technology is developing, users can take screenshots and search for the product they like, even though the video does not promote action. According to one interviewee, “we will take a screenshot and search clothing on Taobao; then, there will appear a message describing ‘the same item seen on TikTok.’” This initiative leads to purchase almost 100% of the time, so the merchant does not need to spend more time persuading the consumer. The ads in a short video ad generate awareness (86% agreement) because an influencer introduces a brand name, sponsor, or the function of the product with lines like “I have coupons for you guys; you can go collect this at blablabla.”

Sometimes, influencers focus on a product without directly acknowledging that they are advertising. According to one interviewee, “we can see a link to the purchase page displayed at the bottom of our screen. We identify an ad by these methods.”

Expenditure

Advertising is about money, however it is paid. Almost 93% of interviewees thought that time, energy, and emotion are more critical than money. One interviewee noted, “the most valuable thing is time. I could make a choice not to watch a traditional ad, but, when it comes to short videos, I do not know it is an ad until I have finished watching it."

Behavioral Change

Interviewees reported often searching for products featured in short videos, with AI graphic recognition technology being able to recognize the screenshots used. This, curiously, occurs without persuasion (86% agreement from interviewees). In addition, big data provides accurate recommendations, so the sponsor does not need to worry about losing these consumers. For

example, one interviewee mentioned, “I chat with my friends about something, and the thing is pushed in other applications I use." Interviewees are able to search for everything they have watched in the short video ads.

Additionally, 43% of interviewees watch short video ads proactively, producing an unexpected storyline. One interviewee commented that the “influencers have always made some interesting short videos, which are funny to us… We like it to watch them more than traditional ads.”

Personal Intellectual Property Media

According to 86% of interviewees, short video allows everyone to be an influencer if they are able to make eye-catching videos. This has lowered the bar, no longer requiring people to work for or hire an advertising agency. Additionally, 5G allows short videos to upload quickly and more big data to be captured. This enables influencers to make longer videos, producing preludes to mitigate hostility to a lengthy ad; ultimately, this results in personal intellectual property media. That is, people who possess a talent or a skill can share it through short videos, turning them into an influencer in that particular field. Then, consumers follow them and support them. However, traditional ads do not possess these characteristics––they do not feature a protagonist, preventing consumer engagement with products or logos alone.

The New Definition

Based on these findings, advertising can be described as:

Personal intellectual property developed through earned, owned, and paid communication channels, activated by an identified or difficult-to-identify source intent on persuading viewers directly, indirectly, or unwittingly to expend energy, time, or emotion (but not money), resulting in behavioral change either now or in the future.

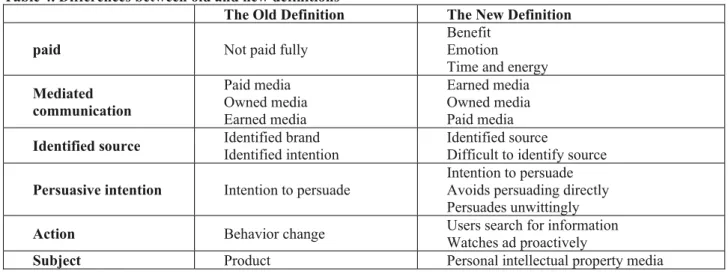

Differences Compared to the Old Definition

Table 4 distinguishes the Kerr and Richards (2020) definition from the new definition.

Table 4. Differences between old and new definitions

The Old Definition The New Definition

paid Not paid fully Benefit Emotion

Time and energy

Mediated communication Paid media Owned media Earned media Earned media Owned media Paid media

Identified source Identified brand Identified intention Identified source Difficult to identify source Persuasive intention Intention to persuade Intention to persuade Avoids persuading directly

Persuades unwittingly

Action Behavior change Users search for information Watches ad proactively

5. Conclusion

Table 4 detailing of the new definition of advertising is localized for contemporary China. Following Kerr and Richards (2020), this study has recognized that “paid” does not adequately describe advertising. We found that Chinese netizens pay more attention to time and energy than money[18]. Given everything requires cost time and energy, they consider time and energy to be more valuable to people who live in a rapidly developing society like China’s. One interviewee said, “I could avoid or not watch a traditional ad, but I think short videos are a story or a funny video but overtaken by an ad. This leaves me helpless more than making me spend money.” We also found that product placement and avoiding persuading directly is appreciated in China. Consumers have always hated advertising, so this makes a diverse yet imperceptible influence. Because advertising is in the storyline, in the comments, in unexpected places, it is difficult to identify ads in short video formats.

Furthermore, due to the development of diverse technologies, consumers are able to search for products they like accurately and quickly. This means advertisers or sponsors do not need to attract them in the moment. On the contrary, imperceptible long-term influence targets the consumer more accurately, not requiring more time to persuade them because big data enables advertisers to find them again and again. This is stimulated by the concept of personal intellectual property. Where the traditional advertising formats needed products or other objects as the subject of the advertisement, the new advertising formats use people as subjects, connecting with consumers more personally (86% agreement).

With the development of society and technology, advertising in other countries could develop in the manner of China; thus, this study might serve as a forecast for academics and practitioners.

Implications for Theory

The new definition more appropriately localizes advertising definitions for China, including Chinese characteristics essential for improving the theory in the future. This study also contributes to a framework for the legal and education system to introduce new policies. However, although the new definition covered more detailed concepts, more wide-range testing is required to understand broader implications, especially beyond the Chinese borders. Additionally, we need to investigate more consumers, especially demographics not included in this study.

References

[1] Arens W., M. Weigold, and C. Arens. 2008.

Contemporary Advertising. New York: McGraw

Hill.

[2] Arens, W.F. 1996. Contemporary Advertising, 6th ed., Chicago: Richard D. Irwin.

[3] Arens, W.F. 2002. Contemporary Advertising, 8th ed., Boston: McGraw Hill/Irwin.

[4] Botev, Z., and A. Ridder. 2017. Variance Reduction. Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online. [5] Brotheridge C.M., R.T. Lee. 2002. Testing A

Conservation of Resources Model of the Dynamics of Emotional Labor. Journal of Occupational

Health Psychology 7, no. 1: 57–67.

[6] Campbell, C., J. Cohen, and J. Ma. 2014. Advertisements just aren't advertisements anymore: A new typology for evolving forms of online advertising. Journal of Advertising Research 54, no. 1: 7–10.

[7] Chang C. 2017. Methodological Issues in Advertising Research: Current Status, Shifts, and Trends. Journal of Advertising 0, no. 0: 1–19

[8] China Internet Network Information Center. 2019. The 44th China Statistical Report on Internet Development. Retrieved from:

http://www.cac.gov.cn/2019-08/30/c_1124938750.htm, Access date: 2020/09/28.

[9] Cross, T. 2011. All the world's a game. The

Economist. 10 December.

[10] Czinkota, M.R. et al. 2000. Marketing: Best

Practices. FL: The Dryden Press.

[11] Dahlen, M., and S. Rosengren. 2016. If advertising won’t die, what will it be? Toward a working definition of advertising. Journal of Advertising 45, no. 3: 334–345.

[12] Dahlen, M., and S. Rosengren. 2016a. If advertising won’t die, what will it be? Toward a working definition of advertising. Journal of

Advertising 45, no. 3: 334–345.

[13] DiStaso, M.W., and B.N. Brown. 2015. From owned to earned media: An analysis of corporate efforts about being on fortune lists. Communication

Research Reports 32, no. 3, 191–198.

[14] Glaser, B.G. 2001. The Grounded Theory

Perspective: Conceptualization Contrasted with Description. Sociology Press.

[15] Goodley, S. 2015. Marketing Is Dead: Says Saatchi and Saatchi Boss— Long Live Lovemarks. The

Guardian, March 3. http://www.theguardian.

com/media/2015/mar/03/advertising-is-dead-says-saatchi-saatchi-boss- long-live-lovemarks, Access date: 2020/09/28.

[16] Hoek, R.W., E. Rozendaal, H.T. van Schie, E.A. van Reijmersdal, and M. Buijzen. 2019. Testing the effectiveness of a disclosure in activating children’s advertising literacy in the context of embedded advertising in vlogs.

[17] Jun, J.S., and S. Baloglu. 2003. The role of emotional commitment in relationship marketing: an empirical investigation of a loyalty model for casinos. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 27, no. 4: 470–489.

[18] Kerr, G., and J. Richards. 2020. Redefining advertising in research and practice. International

Journal of Advertising, DOI: 10.1080/02650487.2020.1769407

[19] Kotler P., K. Keller, A. Koshy, and M. Jha. 2007.

Marketing management: A South Asian perspective,

12th ed. Delhi: Pearson Education Inc.

[20] Kyongseok K., L. Jameson, J. Hayes, A. Avant, and L.N. Reid. 2014. Trends in advertising research: a longitudinal analysis of leading advertising, marketing, and communication journals, 1980 to 2010. Journal of Advertising 43, no. 3: 296-316. [21] Lacznaik, R. 2016. Comment: Advertising’s

domain and definition. Journal of Advertising 45, no. 3: 451–452.

[22] Lee H., and C. Chang-Hoan. 2019. Digital advertising: Present and future prospects,

International Journal of Advertising.

[23] Lee, M. 2014. The Ad Agency Is Dead—Or Is It?.

Forbes, October 29.

http://www.forbes.com/sites/michaellee/2014/10/2 9/the-ad-agency-is-dead-or-is-it/3/#64422d4e625e,

Access date: 2020/09/28.

[24] Liu-Thompkins, Y. 2019. A decade of online advertising research: What we learned and what we need to know, Journal of Advertising, 48, no. 1: 1– 13.

[25] Muncy, J.A., and J.K. Eastman. 1998. The Journal of Advertising: Twenty-Five Years and Beyond.

Journal of Advertising 27, no. 4: 1–8.

[26] N. General Assembly Document A/RES/44/25 (12 December 1989) with Annex Convention on the Rights of the Child.

[27] O'Guinn, T., Allen, C., & Semenik, R. (2013). Promo. Mason, OH: South-Western, Cengage Learning.

[28] Okada E.M., and S.J. Hoch. 2004. Spending time versus spending money. Journal of Consumer

Research 31, no. 2: 313–323.

[29] Olanrewaju Olugbenga, A. and D. Olukemi Okunade. 2016. Evaluating the use of Internet as a medium for marketing and advertising messages in Nigeria. African Journal of Marketing Management 8, no. 2: 12–19.

[30] Pasadeos, Y., J. Phelps, and A. Edison. 2008. Searching for Our “Own Theory” in Advertising: An Update of Research Networks. Journalism and

Mass Communication Quarterly 85, no. 4, 785–806.

[31] Patton, M. Q. 1990. Qualitative Evaluation and

Research Methods. SAGE Publications, Inc.

[32] Pei-Shan, W., and L. Hsi-Peng. 2012. An examination of the celebrity endorsements and

online customer reviews influence female consumers’ shopping behavior. Computer in

Human Behavior 29: 193–201.

[33] Popescu, I.C. 2004. Comunicarea în marketing, Editia a II-a, Editura Uranus, Bucureşti.

[34] Richards, J.I., and C.M. Curran. 2002. Oracles on “advertising”: Searching for a definition. Journal of

Advertising 31, no. 2: 63–77.

[35] Rust, R.T. and R.W. Oliver. 1994. The death of advertising. Journal of Advertising 23, no. 4, 71. [36] Sandra Moriarty, Nancy Mitchell, Charles Wood,

William Wells, University of Minnesota, 2019. Advertising & IMC: principles & practice. New York: Pearson.

[37] Stern B.B. 1990. Pleasure and persuasion in advertising: rhetorical irony as a humor technique.

Current Issues and Research in Advertising 12, no.

1–2: 25-42.

[38] Steven Holiday 2019. Jack and Jill Be Nimble: A Historical Analysis of an “Adless” Children’s Magazine. Journal of Advertising 47, no. 4: 412– 428.

[39] Stewart, D. W. 2016. Comment: Speculations of the future of advertising redux. Journal of Advertising 45, no. 3: 348–350.

[40] Wakefield, J. 2020. TikTok skull-breaker challenge danger warning. BBC.

https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-51742854,

Access date: 2020/09/28.

[41] Yale, L., and M.C. Gilly. 1988. Trends in Advertising Research: A Look at the Content of Marketing-Oriented Journals from 1976 to 1985.

Journal of Advertising 17, no. 1: 12–22.

[42] Youn, S. and K. Seunghyun. Newsfeed native advertising on Facebook: young millennials’ knowledge, pet peeves, reactance and ad avoidance.

International Journal of Advertising 38, no. 5: 651–

683.

[43] Yurieff, K. 2018. TikTok is the latest social network

sensation. CNN.

https://edition.cnn.com/2018/11/21/tech/tiktok-app/index.htm, Access date: 2020/09/28.

[44] Zhang, X., Y. Wu, and S. Liu. 2019. Exploring short-form video application addiction: Socio-technical and attachment perspectives. Telematics