Introduction

An effective marketing system is required in order to ensure the availability of vegetables to consumers at the appropriate time and place. Along with this system, the perishable nature of the vegetables demands high efficiency in terms of marketing and supply chain management (Kumar et al., 2004). This creates a space for the involvement of individuals or groups - known as middlemen - justified in terms of meeting these efficiency objectives. Middlemen are marketing intermediaries that do not add anything tangible to the produce but who still receive a fee for expediting the exchange (Agbebi and Fagbote, 2012); their presence in the supply chain often results in produce being sold to consumers at higher prices than would otherwise be the case

(Bryceson, 1993). Middlemen maintain contact with buyers, negotiate prices, and deliver produce; provide credits or collections; look after the servicing of produce; provide inventory storage, and grading; and arrange transportation (Rubayet and Jony, 2016; Agbebi and Fagbote, 2012). By carrying out these functions, middlemen play an important role in linking smallholder farmers to traders and the final markets (Abebe et al., 2016; Hasan and Bai, 2016). More than 80% vegetables are sold via middlemen (Uddin et al., 2006). Thus, the vegetable supply chain is more than trivially dependent on these middlemen.

The activities of middlemen in developing countries such as Bangladesh could be viewed in terms of improving the efficiency of farmers’ marketing activities. Farmers seek support from middlemen in order to sell their produce

Original Paper

Farmer Preferences in Choosing Middleman Known as Faria as Their Sales Partners in the

Vegetable Supply Chain: A Case Study from the Lalmonirhat District of Bangladesh

Utsarika Singha1* and Shigenori Maezawa2

1United Graduate School of Agricultural Science, Gifu University, Gifu 501-1193, Japan 2Laboratory of Food Logistics Science, Faculty of Applied Biological Sciences, Gifu University,

Gifu 501-1193, Japan

Abstract

Middlemen undoubtedly play a crucial role in the marketing system of any kind of good by connecting producers with consumers. In rural areas of developing countries such as Bangladesh, the marketing channel of the fresh vegetables comprises many stages of middlemen who are often blamed for hiking prices and embezzling farmers’ share of consumer value because the institutional marketing system is not yet well established in remote areas. Faria makes up one stage of the necessary middlemen, and it has been suggested that they are superfluous such that their elimination would result in an increased the share of the final consumers’ price being received by farmers. Contrary to this view, each middleman stage plays a crucial role in the distribution system of any kind of good by connecting producers to consumers. If the farias are removed as middlemen then many other problems may merge, such as the disruption of the rural vegetable supply chain and unemployment of those people who act as faria. This study analyzes farmers’ preference for choosing middlemen for trading of rural vegetables in the marketing system in Bangladesh. Primary data was collected from 131 Bangladeshi farmers from 3 selected villages in the Hatibandha sub-district of Lalmonirhat district, wherein using middlemen is preferred by most area farmers. In this research, the factors that trigger farmers to trade with these middlemen were revealed, even though farmers’ profits would increase if they chose to trade with other middlemen instead. The preferred middlemen were farias. Hence, when undertaking research and formulating policy in this field, it is very important to discover alternative ways through which the farmers may benefit and to take care not to squeeze out income opportunities made available to other persons like middlemen.

Key Words: faria as middlemen, profit, sales partner, vegetable marketing

Journal of Japanese Society of Agricultural Technology Management Vol.26 No.2, 2019 (Lyon, 2000; Fuentes, 1998; Ellis et al., 1997). Overall, five

categories of middlemen are associated with Bangladesh’s vegetable marketing system (Anny et al., 2016), and all of them help to supply vegetables from farmers to consumers. They are farias, who collect product from farm and sell it to either beparis or consumers (Tasnoova and Iwamoto, 2006). The beparis, who collect product from farias or farmers might subsequently sell to arathdars, who tend to handle larger product volumes compared to farias (Das and Hanaoka, 2014). The arathdars, serves as agents in fixed locations, operate between beparis and retailers, and charge a fixed commission for providing storage facilities (Das and Hanaoka, 2014). There also wholesalers, who pick up product from beparis or arathdars and sell in large quantities to retailers. Finally retailers, purchase produce from beparis or wholesalers and sell them to consumers (Anny et al., 2016). These middlemen make the vegetable marketing chain longer in Bangladesh and supposedly exploit farmers by paying low prices (Shrestha and Shrestha, 2000).

Contrary to the view that developing countries like Bangladesh (at least in some areas) became beleaguered with an institutional marketing system it actually evoked a profound influence on economic growth (Nabli and Nugent, 1989). Cooperative marketing is the best example among new institutional economics policies in Bangladesh. Unfortunately, such new institutional economics policies have yet to be established in remote or rural areas of Bangladesh. Traditional marketing procedures are still observed in those areas. Numerous previous studies have suggested that traditional vegetable marketing chains in Bangladesh are inefficient because of the large number of middlemen involved. Among the middlemen, the necessity and importance of farias has always been doubted (Sarker and Sasaki, 2000; Sabur, 1990). As lots of middlemen are directly associated with vegetable trading, the aim of this study is to examine the situation and find out which middlemen are preferred by most farmers selling vegetables and what factors trigger them to trade with these middlemen, under-taking a studies of potatoes and eggplant as sample vegetables. The results indicate that though it would be advisable to introduce the new institutional marketing policies in rural areas as well.

Methodology

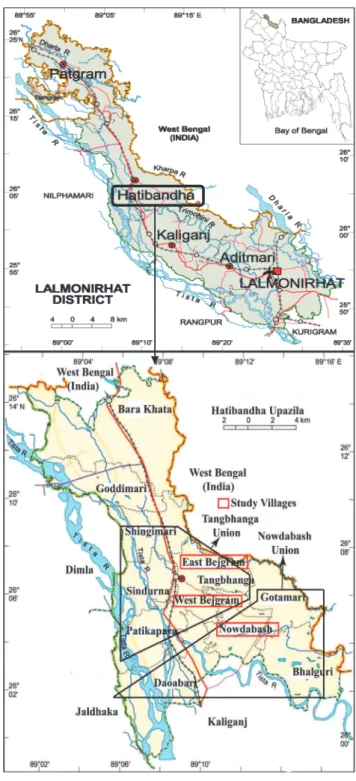

To address the aforementioned objective, we depend principally on primary data collected through a field survey. Data were collected from Bangladeshi producers and all types of middlemen associated with potato and eggplant marketing in three villages from two unions (Tangbhanga and

Nowdabash) in the Hatibandha sub-district of Lalmonirhat district (Fig. 1). The villages are Nowdabash (from the Nowdabash Union) and East Bejgram and West Bejgram (both from the Tangbhanga Union). We focused on these villages because they are the most underdeveloped villages of Bangladesh; most of their residents are farmers, and there are limited alternative employment opportunities. The poverty rate in the studied area was 34.5% compared with 23.2% in the country as a whole (BBS, 2016). In addition,

Fig. 1 Map of the study area.

Source: http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title = Hatibandha_Upazila

Fig. 1. Map of the study area.

Middleman in the vegetable supply chain selected by farmers in Bangladesh

these villages are well-known for potato and eggplant production. Therefore, we chose potato and eggplant as sample vegetables. The majority of farmers in Nowdabash cultivate eggplant and, hence, we did not find any farmers there who did not cultivate it. In East and West Bejgram, farmers mainly cultivate potatoes and eggplant. In total, 131 farmers, 30 farias, 20 beparis, 10 arathdars, 10 wholesalers, and 15 retailers are associated with the potato and eggplant marketing chain, and these links were surveyed using a structured questionnaire in April 2017.

A simple random sampling technique was used to obtain the observations. Among the 131 farmers, 106 produced both crops, while 121 and 116 indicated that they produced potatoes and eggplant, respectively. We captured information about farias from farmers, and then proceeded to collect data from those farias whose business was associated with both potatoes and eggplant. Furthermore, we dichotomized middlemen into farias on the one hand and all other middlemen (beparis, arathdars, wholesalers, and retailers) on the other. Except for the farias, all other middlemen were grouped together because rural farmers have a tendency to trade with farias first. The importance of farias was

Fig. 2 Current potato (A) and eggplant (B) marketing channel in the study area. Data source: Author survey, April 2017

identified by the view of the farmers. A survey pertaining to farias was conducted to identify the factors behind their activities as well as their profitability. Beparis, arathdars, wholesalers, and retailers were surveyed to confirm their sources for purchase of produce. Data pertaining to other middlemen were collected from the Hatibandha market. These middlemen were also associated with trading in both potatoes and eggplant. The sampled farmers, farias, and related middlemen information are summarized in Table 1.

Results and Discussion 1. Present marketing chains

a. Potatoes

The entire potato marketing system is shown in Fig. 2A. During the potato harvesting period, farmers sold most of their produce to middlemen, stored some in cold storage, and sold a small fraction directly to consumers. Certainly, most potatoes were collected by the farias from farmers at their farms. During peak production times, beparis also visited farmers to buy larger volumes. Due to the substantial production of potatoes, a considerable portion would be sold by rural beparis to urban wholesalers.

Potato Eggplant

Rural harvesting and consuming area Urban consuming area

Rural harvesting and consuming area

Urban consuming area

Fig. 2. Current potato (A) and eggplant (B) marketing channel in the study area.

Data source: Author survey, April 2017

Farmer Farmer

Cold storage owner Bepari Faria Arathdar

Wholesaler Retailer Consumer

Wholesaler for urban marketing

A B Bepari Faria Arathdar Wholesaler Retailer Consumer

Journal of Japanese Society of Agricultural Technology Management Vol.26 No.2, 2019

of their profits. Even though the age and educational level of the farmers were differed considerably, the marketing information they needed required them to pay similar operational costs to sell their produce. Production costs for both groups were similar except for transportation costs and marketplace taxes that needed to be paid by “selling to other middlemen groups.” Therefore, we calculated gross profit by a simple formula “Sales price X Production volume - Production cost” (including transportation and marketplace taxes). Table 2 shows the gross profit of farmers after selling their produce to farias and other middlemen. The gross profit and benefit-cost ratio (BCR) for potatoes were 6,260 in the Bangladeshi currency- Taka (BDT) and 1.42, respectively, when their produce was sold to farias; and when their produce was sold to other middlemen, both figures increased to BDT 6,920 and 1.44, respectively. Similarly, when eggplant was sold to other middlemen, gross profit and BCR b. Eggplant

The entire eggplant marketing system is shown in Fig. 2B. The marketing channel of eggplant is similar to that of potatoes, excluding cold storage. Farias also play an important role in collection of eggplant from farmers. Similar to potatoes, farmers were more interested in selling their product to farias than to other middlemen. Beparis then bought eggplant from farias, and sold it to wholesalers via

arathdars. Retailers mainly depended on wholesalers for

their supply. Occasionally, farmers sold eggplant directly to retailers in Hatibandha’s marketplace, but this occurred infrequently because when farmers arrived at the market,

beparis try to buy their product.

2. Understanding farmers’ preferences in trading At first we calculated the farmer’s gross profit from their cultivated vegetables and identified when they got most

Vegetables Village Farmers Farias Beparis Arathdars Wholesalers Retailers

Potatoes N 54 15 4 2 4 3 EB 31 07 4 1 2 3 WB 36 08 3 3 1 2 Eggplant N 63 15 4 2 2 3 EB 25 07 2 0 1 3 WB 28 08 3 2 0 1

N = Nowdabash, EB = East Bejgram, WB = West Bejgram, Data source: Author survey, April 2017 Table 1 Sampled farmers distribution in studied areas (n = 121 for potato and n = 116 for eggplant) and

middlemen: farias (n = 30), beparis (n = 20), arathdars (n = 10), wholesalers (n = 10), retailers (n = 15).

Table 2 Gross profit analysis of potato and eggplant farmers: trading with farias or other middlemen (in BDT*).

Parameters Faria Potato Others Faria Eggplant Others

1. Production costs (Av.)/ 27 decimiles (in BDT*) a. Seed

b. Fertilizer c. Pesticides d. Irrigation

e. Labor cost (including family labor and harvesting cost)

f. Transportation cost g. Taxes paid in market

4320 4590 2080 150 3600 4320 4590 2080 150 3600 600 240 500 4890 4160 1500 84000 500 4890 4160 1500 84000 720 360

2. Total cost (in BDT*) 14740 15580 95050 96130

3. Total production 30 sack*** 30 sack*** 360 mound** 360 mound**

4. Total income after selling (in BDT*) 30 × 700*=21000 30 × 750*=22500 360 × 350*=126000 360 × 400*=144000

5. Gross profit (4-2) (in BDT*) 6260 6920 30950 47870

6. Benefit Cost Ratio (BCR) 1.42 1.44 1.33 1.50

*BDT = Bangladeshi currency (Taka), **1 mound =40 kg, ***1 sack=85 kg Data source: Author survey, April 2017

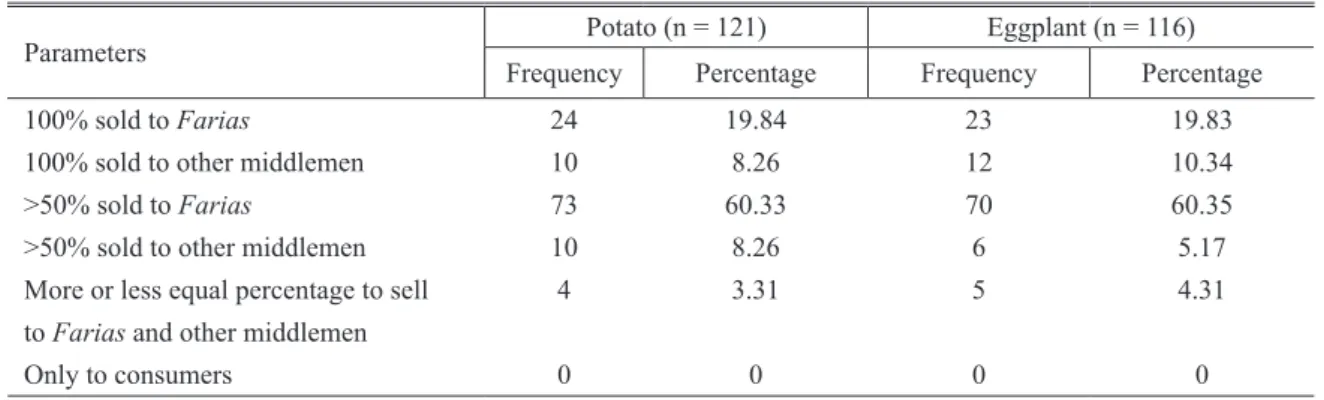

Table 3 Farmers’ choice distribution: trading with farias or other middlemen.

Parameters Potato (n = 121) Eggplant (n = 116)

Frequency Percentage Frequency Percentage

100% sold to Farias 24 19.84 23 19.83

100% sold to other middlemen 10 8.26 12 10.34

>50% sold to Farias 73 60.33 70 60.35

>50% sold to other middlemen 10 8.26 6 5.17

More or less equal percentage to sell 4 3.31 5 4.31

to Farias and other middlemen

Only to consumers 0 0 0 0

Data source: Author survey, April 2017

were 47,870 BDT and 1.50, respectively, which was more than that of the faria. Even though the farmers earned a higher profit by selling their product to other middlemen, their preference was to sell to farias because farias did some beneficial activities for the farmers. So, there the presence of certain additional factors influenced farmers to trade with the farias. Issues influencing farmers to trade with the

farias are described below. According to farmers’ opinions,

it is somewhat hazardous to sell their produce to other middlemen. To do so, they need to go to the Hatibandha marketplace or another nearby market. This process is time consuming, entailing additional transportation costs that are high because of vehicle unavailability and poor road conditions. Moreover, calculation of the opportunity cost to cultivate potatoes and eggplant instead of other crops such as rice or wheat is somewhat difficult because regional farmers are mostly familiar with cultivating potatoes and eggplant. In the market, they need to pay taxes and other associated fees. However, farias enter into the equation by coming to the farm when a farmer requests them to do. At harvest time they roam all around the village collecting produce. So, it is an easy and time-saving method to sell produce to them.

Among many farias, the farmer may choose their sales partners. Farmers choose them for various reasons, but before explaining them we need to clarify the essentials elements of the two groups. The nature of trading among farmers was grouped into farias and other middlemen depending on the amount of potatoes and eggplant sold (>50%) to farias and to other middlemen. Table 3 shows the basic criteria for such categorization. As trading with other middlemen by farmers was an uncommon choice, we categorized those who sold their product equally to farias and other middlemen into the “other middlemen” group. As all farias come to the farmhouse, we eliminated this reason as being fundamental in underlying the farmer’s choice of a faria. Fig. 3 shows the reasons why farmers choose specific farias to trade with. Farmers always try to sell their product to those faria who offer a good price in the case of potatoes. After that, they preferred cash exchanges because they want to be paid immediately rather than suffering some delay. Farmers also mentioned some other reasons for their preferences, such as buying large amounts at one time, being a trusted person, less bargaining required, and help during cultivation. In the case of eggplant, farmers sold their product to those

farias who wanted to buy a large amount of produce at one

time because at the peak production time farmers harvest a large amount of produce. Beyond that constraint, they also appreciated those who offered a good price, immediate cash after selling, help during harvest, and so on.

The preferences of farmers (faria-oriented vs. other-middlemen oriented) were calculated by using the t test (Table 4). The results suggest a positive relationship between farmers’ ages and willingness to trade with farias. This fact appears to back the notion that the older generation in Bangladesh places a premium on avoiding irksome and complex elements. Hence, older farmers may be more likely to support the status quo vis-à-vis trading with farias rather than seeking out alternative options. The corollary of this Fig. 3. Important reasons for trading with farias.

Data source: Author survey, April 2017 Number of farmers Fig. 3 Important reasons for trading with farias.

Journal of Japanese Society of Agricultural Technology Management Vol.26 No.2, 2019

situation is that important social ties exist between farias and farmers, which constitute a crucial non-market benefit of maintaining trade relationships. Indeed, various studies have explored this idea (e.g., Alesina and Ferrara, 2005; Hoffman et al., 1998; Fehr et al., 1997; Granovetter, 1985). This finding also resonates with Abebe et al., 2016 and Koutsou et al., 2014 who observed that, at the other end of the spectrum, younger farmers have limited trust in people and institutions. Additionally, elderly farmers have traded with farias for long periods, during harvest and through times of economic crisis time they get help from farias, who even lend them money, which makes farias more trustworthy than other middlemen (Fig.3). Furthermore, we found that more educated farmers exhibited a greater tendency to trade with other types of middlemen; this fact supports the standard tenets of neoclassical economics, for example, the importance of militating against information asymmetries. Educated farmers are always conscious about the market situation. Therefore, the result of this study also supports this view. Since educated farmers are keenly conscious about the market, they sell their product to other middlemen if they are offered more than the farias are willing to pay. Educated farmers get market information by reading the newspapers, as television was uncommon in the study area. Market information was also provided by radio at a fixed time every two hours during the day but illiterate farmers miss it due to their relative unconsciousness. Therefore, sometimes the farias provide partially incorrect

information to illiterate farmers when buying their produce. The result of the t test (Table 4) also showed the presence of a significant difference between the two groups: (1) faria-oriented farmers (n = 101 and 98 for potato and eggplant, respectively) and (2) other-middlemen-oriented farmers (n = 20 and 18 for potatoes and eggplant, respectively). In addition, farmers who cultivate a relatively large plot of land (in both the potato and eggplant cases) tend to sell their product to the farias. The reasons behind this phenomenon were that, when the land size is large, production will be vast, and farmers will try to sell their large quantity of produce immediately after harvesting, at once, and thus they consider farias given that they are always roaming around the area. So, the large scale of farm-land plays an influential role to selecting a trading partner for farmers. Farmers who owned livestock also sold their product to farias, which was contrary to our expectations (see for example Abebe et al, 2016). However, this result can perhaps be explained in terms of time demands on farmers who simultaneously own livestock and produce vegetables; these time demands serve to exacerbate transaction costs associated with trading with middlemen other than farias.

Importantly, for farmers, during peak production, when they went to trade large volumes of produce, the farias were easily accessible. This feature is appealing to farmers given the time-critical nature of perishable vegetables as noted above. If farias are on-hand at peak times, the risk of large-scale waste through perishing can be minimized. Farmers Table 4 Factors influencing farmers’ willingness to trade based on t-test.

Factors

Potatoes Eggplant

Levene’s Test for

Equality of Variances t-test for Equality of Means Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances t-test for Equality of Means F Sig. t df Sig. (2 tailed) F Sig. t df Sig. (2 tailed) Age Equal variances assumed 3.02 0.085 2.80 119 0.006*** 3.69 0.057 2.87 114 0.005***

Equal variances not assumed 3.28 44.40 0.002*** 3.53 46.56 0.001*** Family size Equal variances assumed 1.33 0.249 0.25 119 0.801 1.04 0.308 0.67 114 0.503

Equal variances not assumed 0.27 39.84 0.783 0.74 38.80 0.461 Education Equal variances assumed 6.49 0.012 -3.38 119 0.000*** 11.74 0.000 -3.75 114 0.000***

Equal variances not assumed -3.79 41.25 0.000*** -4.57 45.87 0.000*** Livestock no. Equal variances assumed 1.39 0.240 0.47 119 0.637 0.32 0.569 0.26 114 0.790

Equal variances not assumed 0.51 40 0.607 0.28 36.66 0.778

Total land Equal variances assumed 8.13 0.005 2.18 119 0.030** 21.74 0.000 2.61 114 0.010*** Equal variances not assumed 4.16 114.83 0.000*** 4.41 103.66 0.000*** Potato land Equal variances assumed 4.70 0.032 1.64 119 0.102* -- -- -- --

--Equal variances not assumed 3.27 101.51 0.001*** -- -- -- -- --Eggplant land Equal variances assumed -- -- -- -- -- 10.36 0.001 2.36 114 0.019**

Equal variances not assumed -- -- -- -- -- 4.27 113.82 0.000*** ***significant at 1%, **significant at 5%, *significant at 10% level of significance. Data source: Author survey, April 2017

Middleman in the vegetable supply chain selected by farmers in Bangladesh

do not grade their produce, which generates a disincentive for other types of middlemen who might otherwise purchase directly from farmers. After collecting produce from farmers,

farias grade it, which also appeals to farmers because they

regard doing so as hazardous work.

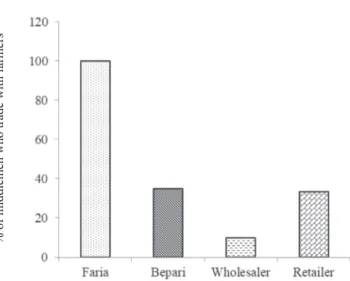

3. Influence of trading with farias by farmers

The validity of farmers’ views was assessed by a counter survey given to the farias and other middlemen whether or not they had bought produce from farmers. Except for the

arathdars, all other middlemen said that very often they

buy product from farmers because farmers cannot supply the product demanded of them. Those middlemen who buy product at least twice a week during peak production time are considered to be farmers-oriented middlemen. All farias, 7 beparis, 1 wholesaler, and 5 retailers buy commodities twice a week from the farmers: 100%, 35%, 10%, and 33.33%, respectively (Fig. 4), shows the nexus or pattern and the importance of the farias in the potato and eggplant marketing chain in the study area. Basically, this section deals with the hypothesis aiming to investigate farmer preferences for choosing a selling partner in the rural vegetable supply chain. To identify this facet, we calculate the gross profit of potatoes and eggplant after selling to

farias and other middlemen. The gross profit is calculated

by subtracting the total production cost from total income after selling. The production cost comprises the cost of seed, fertilizer, pesticides, irrigation, labor, transportion and taxes, and some other marketplace costs (Brees, 2002). From the data analyzed, it is easily measurable by the naked eye that even though the farmers profit little by selling their product to farias, they want more money yet also want to maintain

trade with the farias, generating an antagonistic situation (Govindasamy et al., 1999). According to the farmers’ viewpoints, some specific reasons are responsible for trade with farias. Among several criteria, major points in favor of using these middlemen are as follows: (1) a good price often offered by farias, (2) the need to do less bargaining to sell one’s product, (3) most farias pay cash at the time of exchange, and (4) they are often well-known to farmers, just as his relatives or neighbors. Sometimes, people of the same religion act as farias and frequently try to help farmers. Indeed, they always try to manage the farmers by their good behavior and, as a result, become trusted men. However, despite the aforementioned reasons the reasons why the situation is so antagonistic still need to be clarified by future research.

Conclusion

Results showed that middlemen called farias facilitated the selling procedure for farmers by their various helpful activities. Thus, farias generally improve the condition of the vegetable supply chain in rural areas. There were significant differences between the farmers who chose to use a faria as their selling partner and farmers who chose other middlemen. Most of the farmers preferred to work with a

faria. Just to name a few elements, this preference resulted

from the fact that farias buy large amounts of produce at a time, conveniently roaming around the farming area, they are especially convenient for formers that cultivate larger plots, who are older, whose education levels influenced the preference of farmers to choose selling partner in various ways. Therefore, to improve this situation as well as to increase the farmers’ share of the retail price, the government needs to formulate logistical and agricultural policies such as setting up a cooperative marketing system, establishing a market-monitoring cell, strengthening the agricultural service providing offices, training farmers, establishing a cold storage center, and improving infrastructure and communication systems in the rural areas of Bangladesh where agriculture is a driving force in the local economy.

References

Abebe, G. K., J. Bijman and A. Royer. 2016. Are middlemen facilitators or barriers to improve smallholders` welfare in rural economics? Empirical evidence from Ethiopia. J. Rural Stu. 43: 203-213.

Agbebi, F. O. and T. A. Fagbote. 2012. The role of middlemen in fish marketing in Igbokoda fish market, Ondo-state, south western Nigeria, Intl. J. Dev. Sus. 1: 880-888.

Alesina, A. and E. L. Ferrara. 2005. Ethnic diversity and

Fig. 4. Middlemen’s percentage of buying vegetable from farmers. Data source: Author survey, April 2017

% o f m id dl em en w ho tra de w ith fa rm er s

Fig. 4 Middlemen’s percentage of buying vegetable from farmers.

Journal of Japanese Society of Agricultural Technology Management Vol.26 No.2, 2019 economic performance. J. Econ. Lit. 43: 762-800.

Anny, S. A., S. Afrin and A. Akter. 2016. Interference of middlemen on vegetable price: with reference to Brinjal marketing channel in Bangladesh. Intl. J. Mana. Econ. Invt. 2: 1043-1055.

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, BBS. 2016. Yearbook of agricultural statistics of Bangladesh, 2010. Statistics Division, Ministry of Planning, Government of the People`s Republic of Bangladesh. www.bbs.gov.bd

Brees, M. 2002. Budgeting for value: generic horticulture crop cost-return budget for Missouri. Farm Management Guide. University of Missouri Columbia, FBM-6001.

Bryceson, D. F. 1993. Liberalization of Tanzania food trade: public and private faces of urban marketing policy (1938-1988), United Nations research institute for social development, Geneva, Switzerland.

Das, R. and S. Hanaoka. 2014. Perishable food supply chain constraints in Bangladesh. Intl. J. Food Sup. Cha. 5: 13-29. Ellis, F., P. Senanayake and M. Smith. 1997. Food price policy

in Sri Lanka. Food policy. 22: 81-96.

Fehr, E., S. Gächter and G. Kirchsteiger. 1997. Reciprocity as a contract enforcement device: experimental evidence. Econ. J. Econom. Soci. 65: 833-860.

Fuentes, G. A. 1998. Middlemen and agents in the procurement of paddy: institutional arrangements from the rural Philippines. J. Asian Econ. 9: 307-331.

Granovetter, M. 1985. Economic action and social structure: the problem of embeddedness. Am. J. Socio. 9: 481-510. Govindasamy, R., F. Hossain and A. Adelaja. 1999. Income of

farmers who use direct marketing. Agril. Reso. Econ. Rev. 28: 76-83.

Hasan, M. R. and H. Bai. 2016. Vegetable marketing system and roles of middlemen in Bangladesh, BD. J. Prog. Sci. Tech. 14: 1-6.

Hoffman, E., K. A. McCabe and V. L. Smith. 1998. Behavioral foundations of reciprocity: experimental economics and evolutionary psychology. Econ. Inq. 36: 335-352.

Koutsou, S., M. Partalidou and A. Ragkos. 2014. Young farmers` social capital in Greece: trust levels and collective actions. J. Rural Stu. 34: 204-211.

Kumar, A. K., R. B. Atteri and P. Kumar. 2004. Marketing infrastructure in Himachal Pradesh and integration of the Indian apple markets. Ind. J. Agril. Mark. 18: 243-252. Lyon, F. 2000. Trust, networks and norms: the creation of

social capital in agricultural economics in Ghana. World Dev. 28: 663-681.

Nabli, M. K. and J. B. Nugent. 1989. The new institutional economics and its applicability to development. World Dev. 17: 1333-1347.

Rubayet, K. and B. Jony. 2016. Value stream analysis of vegetable supply chain in Bangladesh: a case study. Intl. J. Man. Value Sup. Cha. 7: 41-60.

Sabur, S. A. 1990. Production and price behavior of vegetables in Bangladesh. BD. J. Agril. Econ. 13: 81-91.

Sarker, A. L. and T. Sasaki. 2000. Role of Middlemen in Marketing System: The Case of Potato and Banana Marketing in Bangladesh. Japanese J. Farm Man. 37: 147-152.

Shrestha, B. and R. L. Shrestha. 2000. Marketing of Mandarin orange in the western hills of Nepal: constraints and potentials. Lumle Agricultural Research Station, Nepal. Tasnoova, S. and I. Iwamoto. 2006. Kataribhog rice marketing

system in Dinajpur District, Bangladesh. Memoirs of the Faculty of Agriculture, Kagoshima University. 41: 19-50. Uddin, M. M., M. A. Mannaf, M. A. H. Talukder, M. B. Islam,

A. K. Saha, S. M. A. H. M. Kamal and S. Hasan. 2006. Farm level vegetable production in northwest Bangladesh-experience of a GO-NGO collaborative program. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 9: 385-390.