Evaluation of behavioural need of tethered cattle from jumping and

running behaviour when they were released to the paddock

Fuko NAKAYAMA, Shigeru NINOMIYA*

Gifu University, Graduate School of Applied Biological Sciences, * Gifu University, Applied Biological

Sciences, 1-1 Yanagido Gifu, 501-1193, Japan

*Corresponding author. E-mail address: nino38@gifu-u.ac.jp

Summary

Tethering is expected to be stressful for restrained cattle because they are unable to express appropriate behaviour. This study was conducted to elucidate their motivation to move by observing the behavioural reactions of tethered cattle when released to a paddock. We examined 16 Japanese black cattle of four groups. Animals that had been tethered in a pen the first 10 days were released to an outdoor paddock every day: 9:30–14:30 (TR). Subsequently, by preventing their release for one day (PR1) or 6 days (PR6), we observed responses to being tethered for three durations. After each tethering period had finished, animals were released to the paddock for 5 h. Then their behaviours were filmed for 60 min immediately following their release. From the video, their frequencies of jumping and running were observed. Furthermore, to evaluate cattle behaviour restriction by tethering, we compared the individuals’ various behaviours when tethered to those when they were released. Jumping and running were observed more for PR6 than for TR (P < 0.05, Dunnett’s test). Jumping, running, and mock sexual behaviours were not observed when tethered. Results suggest that cattle tethered for 6 days became increasingly motivated to move during restriction by tethering.

Keywords: cattle, jumping, motivation, running, tethering

Animal Behaviour and Management, 54 (4): 165-172, 2018 (Received 5 November 2017; Accepted for publication 19 November 2018) Introduction

Tethering is one method of cattle management that has been adopted widely in Japan because it offers management benefits: ease of management, and prevention of agonistic behaviour, and prevention of feed competition among the cattle. However, from the perspective of animal welfare, concern has arisen in recent years that tethering strongly restricts normal behaviour expression, which might cause frustration when tethered because the motivation to move is not satisfied. A study of cattle that were transferred from a pasture and tethered indoors revealed that the level of cortisol (Redbo 1993; Higashiyama et al. 2005) and the expression of stereotypies (Redbo 1993) increased during several weeks after tethering. These results demonstrate that

tethering can be a stressor for cattle. Therefore, when adopting tethering for cattle, one must periodically release tethered cattle to a paddock for exercise. Nevertheless, it remains unclear how long a period of tethering causes frustration in cattle. Therefore, it is necessary to clarify the accumulation of motivation to move while tethered and unable to move freely.

The expression of locomotor behaviour when released to a wide open space after confinement has been used to measure an animal’s level of motivation to move, which rises during behavioural restriction. Reportedly, calves confined by tethering or by a narrow pen, when released to an open field, express locomotor behaviours such as jumping and running. Moreover, they do so to a greater degree than they do before tethering or when kept in a loose pen group (Dellmeier et

al. 1985; Jensen 1999; Sisto & Friend 2001). It is often inferred that behavioural rebound occurs: a certain behaviour increases after restriction. Such a rebound might reflect an endogenous motivation to move that has been built up during confinement (Jensen & Toates 1993; de Passillé et al. 1995; Jensen 1999). However, calves that are regarded as having higher motivation to exercise have been used for such studies investigating the behavioural motivations of confined animals. Very few studies have examined adult cattle. A study by Jensen (1999) examined heifers kept in a loose stall. They were tethered continuously for a certain period: 1 week, 2 weeks, or 4 weeks. After each tethering period, they were released to the paddock. These results demonstrate that, when released, tethered heifers galloped and bucked more than non-tethered ones. However, no clear difference in the expression was found because of the difference in the tethered period, which suggests that accumulation of the motivation to move might reach a plateau within about one week. Furthermore, the tethered cattle stress was evaluated as the change from when individuals were not tethered (e.g., grazing) to tethered, with recording of physiological and behavioural reactions during and after tethering (Redbo 1993; Jensen 1999; Higashiyama et al. 2005, 2007). The behaviour might be influenced not only by the confinement period but also by acute stress caused by the change of environment in individuals that are not accustomed to tethering.

Therefore, by observing behaviours of tethered cattle when released to the paddock, this study clarifies their cumulative motivation to move. In the experiment, to ascertain the direct influence of the tethering period, tethered cattle were allowed into an outdoor paddock for 5 h each day. The cattle were familiar with the tethered– release process. Subsequently, by stopping the release for a certain period (1 day, 6 days), we made different tethering period lengths. If motivation to move had accumulated for one week, then we predicted that a longer tethering period would elicit longer expressions of jumping and running from tethered cattle that were released to the paddock. By comparing the behavioural repertoire expressed when cattle were tethered to that when released, we assessed whether tethering affected the cattle behaviour.

Methods

This study was approved by the committee of animal experiments of Gifu University (No. 14051).

2.1. Animals, housing, and feeding

This study was conducted during August– November 2014 at the Gifu University Field Science Center, Minokamo (137 °03'57.1"E, 35 ° 26'44.6"N), Japan.

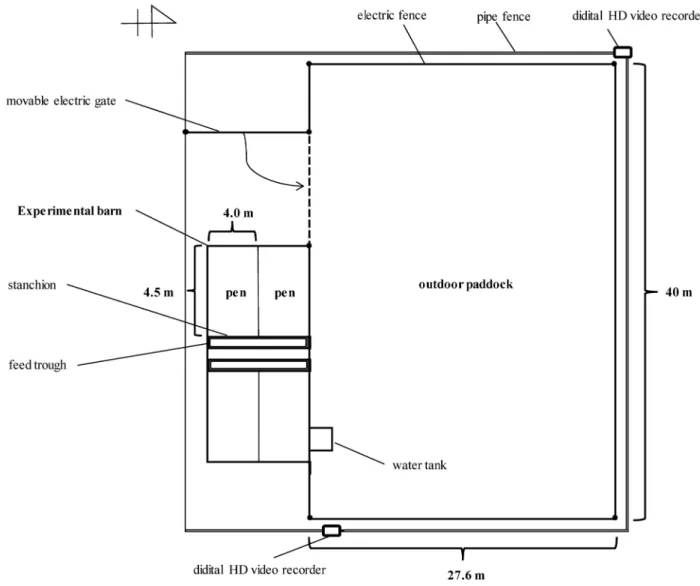

The study examined 16 female Japanese black cattle of 41.5 (SD 21.7) months age, weighing 321.8 (SD 38.5) kg. They were divided into four groups. Each group was tested individually. Considering compatibility among individuals, groups consisted of cattle of similar ages. Animals of similar age are often kept in the same environment, sharing long relationships from childhood. For that reason, they are usually on good terms. To suppress behavioural fluctuation attributable to oestrous cycles, cattle that were confirmed as pregnant were used. Before the experiment, individuals were marked differently on both sides of the abdomen using hair decolorant (Men’s Palty Energy Bleach EX; Dariya Co. Ltd., Aichi, Japan). All cattle had experience of grazing outdoors and being restrained by tethering in an indoor pen. The experiment was conducted in a barn and a neighbouring outdoor paddock (Figure 1). The barn had four pens of 4.0 m × 4.5 m (18.0 m2), of which two were used

for the test. Heifers that were unrelated to the experiment were in the remaining two pens. When the experimental period started, four cattle of one group were moved to the experimental barn and were tethered side by side with a rope. One end of the rope was tied to the wooden frame of the stanchion in the front of the feed trough; the other end was tied to their horns, passing through the nose ring. The rope’s range of motion was 70 cm. All pens had concrete floors that were covered with sawdust. In front of the pens, there were feed troughs, water cups, and mineral salts. No partitions separated them from other cattle; they were able to have contact with neighbouring cattle. Throughout the experiment, all cattle were offered fescue straw and wheat bran twice a day at 08:00 and at 14:30. The amount of feed followed the Japanese Feeding Standard for Beef Cattle (National Agriculture and Feed Research Organization 2008). The outdoor paddock was 27.6 m × 40.0 m (1104 m2). The paddock floor was

covered with sand and some weeds that the cattle were able to graze upon. The paddock, which had a water tank, was enclosed by a movable electric fence with a gate through which cattle were able to enter and leave the indoor pen.

2.2 Experimental treatments

Groups of four cattle were moved to the experimental barn and were tethered in the pen. From the next day, the experimental period of 19 days started. The first 10 days were “tethered– released treatment” (TR). In this treatment, cattle were released to the outdoor paddock during 9:30 to 14:30. After the release time was finished, cattle were taken into the experimental barn and were tethered in the pen until the next day and release time. Therefore, the tethering time was 19 h. By repeating this treatment for 10 days, the

cattle became accustomed to those conditions. The next day after 10 days of TR finished, cattle were prevented from release to the paddock, instead remaining tethered in their pen. Subsequently they were released to the paddock simultaneously for 5 h. We designated this treatment as “preventing for 1 days treatment” (PR1). After PR 1, the “preventing for 6 days treatment” (PR6) was performed. For 6 days from the time PR1 finished, cattle were prevented from release to the paddock. Subsequently, they were released to the paddock for the same time. The respective tethering times were 19 h in TR, 43 h in PR1, and 163 h in TR6. 2.3 Behavioural recordings

The behaviours of all cattle of the respective tethering treatments were video-recorded for 60 min immediately after release to the paddock.

Figure 1. Experimental environment.

The experimental barn had four pens of 4.0 m × 4.5 m, of which the upper two were used for this study. Cattle were tethered in the pen and released to the outdoor paddock during 9:30 up to 14:30. During the release, the paddock was enclosed by the movable electric gate.

We used two digital HD video recorders (HDR-CX535, HDR-CX180; Sony Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The TR data were those of the day immediately before PR1.

Behaviours of all cattle during tethering in the pen were recorded 24 h from the second day up to the third day during PR6. The experimental barn had three CCD cameras (HCIR-41F690; Hoga, Kyoto, Japan) and four infrared ray projectors (WTW-F6085; Wireless Tsukamoto Co., Ltd., Mie, Japan).

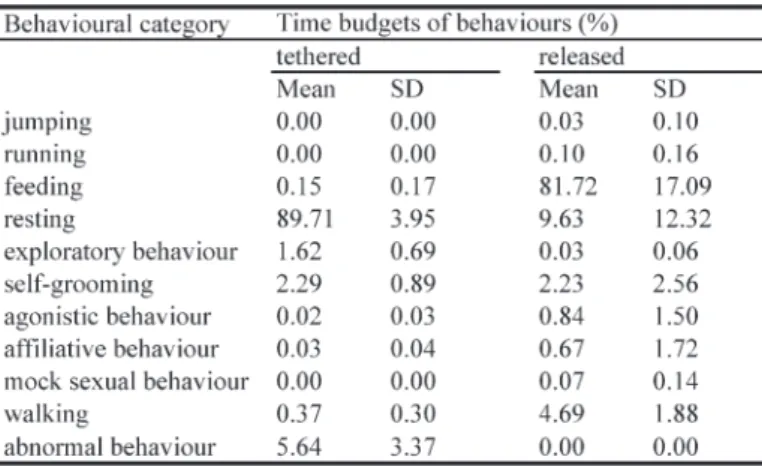

From the continuous video recordings, we observed all behaviours. The observation durations when cattle were released to the paddock were 60 min immediately after release. Those of tethered cattle were for 16 h of 18:00–7:30 and 10:30–13:00. Categories and time budgets of the respective behaviours were calculated. For comparison to the behaviours recorded when cattle were released, TR data for one hour were used. The behavioural categories were defined as presented in Table 1.

2.4 Data and statistical analysis

For comparison of behaviours observed when cattle were tethered and when they were released, we calculated the share of time spent performing respective behaviours during the observation time. For data of individuals and each treatment when released to the paddock, we calculated the frequencies of running and jumping, and the running duration. These data were analysed using software (Minitab ver. 17.2 ver. Japanese 2014; Kozo Keikaku Engineering Inc., Tokyo, Japan). For overall data not following a normal distribution, logarithmically transformed data that approximate a normal distribution were used for analyses. To all data for which data values were zero was added 1 before logarithmic transformation. A general linear model (GLM) was used to assess the

treatment effects. Behavioural data were used as dependent variables. In the model, treatment (TR, PR1, PR6) was used as a fixed factor, with animal (individual cows) nested within group (four groups) and group were used as random factors. Data between TR and PR1 or PR6 were compared using Dunnett’s test. The significance level of tests was set as 5%.

Results

The behavioural repertoire shown in the experiment is presented in Table 2. When tethered cattle were released to the paddock, they showed jumping, running, feeding, resting, exploratory behaviour, self-grooming, agonistic behaviour, affiliative behaviour, mock sexual behaviour, and walking. However, the behavioural repertoire when tethered in an indoor pen included feeding, resting, exploratory behaviour, self-grooming, agonistic behaviour, affiliative behaviour, walking, and abnormal behaviour. When cattle were tethered, jumping, running, and mock sexual behaviour were not observed.

The frequencies of jumping and running when cattle were released to the paddock are shown in Figure 2. Frequencies of jumping per individual per hour (mean ± SE, n = 16) were 1.3 ± 0.9 for TR, 3.4 ± 1.3 for PR1, and 8.3 ± 3.1 for PR6. They were found to be significantly different among the treatments (F2, 30 = 6.81, P < 0.01).

Jumping occurred significantly more for PR6 than for TR (P < 0.05). The frequencies of running per individual per hour were 0.9 ± 0.3 for TR, 1.8 ± 0.5 for PR1, and 3.2 ± 0.9 for PR6 (mean ± SE, n = 16). They were significantly different among the treatments (F2, 30 = 7.34, P < 0.01).

Running occurred significantly more for PR6 than for TR (P < 0.05). The frequencies of jumping and running were 2.1 ± 1.1 for TR, 5.1 ± 1.7 for PR1, and 11.4 ± 3.9 for PR6 (mean ± SE, n

= 16). They were significantly different among the treatments (F2, 30 = 6.66, P < 0.01). Jumping and

running occurred more for PR6 than for TR (P < 0.05). The durations of running per individual per hour were 3.6 ± 1.5 s for TR, 11.4 ± 3.2 s for PR1, and 22.4 ± 7.1 s for PR6 (mean ± SE, n = 16). They were significantly different among the treatments (F2, 30 = 7.39, P < 0.01). The running

duration was significantly greater for PR6 than for TR (P < 0.05). Three cows showed no jumping

or running when released to the paddock after restraint for any tethering period.

Discussion

Comparison of behavioural repertoires observed when cattle were tethered and when cattle were released revealed differences in jumping, running, and mock sexual behaviour. Our results suggest that expression of these

Figure 2. The mean of behavioural frequency or duration when cattle were released to the paddock after TR, PR1 and PR6.

The error bars show standard error (n = 16). In TR, animals were released to an outdoor paddock during 9:30 to 14:30 every day. PR1 or PR6 means preventing the release for one day or 6 days. * denotes significant difference between the data of TR and PR6 (P < 0.05, Dunnett’s test).

Table 2 Behaviour and time budgets of cattle when tethered in an indoor pen and when released to the outdoor paddock

behaviours was restricted by tethering because these behaviour expressions were accompanied by larger body movements than that shown by other behaviours. When the tethered cattle were prevented from release to the paddock for 1 day or 6 days and were then released to the paddock, they showed more jumping and running after release following 6 days than before they were prevented. This result supports those reported by Jensen (1999), suggesting that behavioural needs accumulation occurs within one week after behavioural restriction. However, in the study reported by Jensen (1999) cattle were not tethered in the control condition. Therefore our results are the first to reveal that extension of the tethering period for 6 days would build up behavioural needs in cattle and induce the behavioural rebound in cattle.

However, times for which accumulating needs for behaviour starts were not clarified in our study because the cattle did not show significantly more jumping and running after release following 1 day than they did before. In calf studies, calves that were prohibited from play area access for one day or 3 days showed significantly more locomotor play (galloping, bucking, and buck-kicking) when released to a play area after 3 days (Jensen, 2001). Sisto and Friend (2001) also reported that behavioural restraint for 2 days had no effect on calf movement motivation. Based on these findings, it is likely that the point of accumulation of behavioural needs of calves is 3 days after starting the behaviour restriction. We would probably need to include the period within 2 days to 1 week in future experiments of behavioural needs accumulation of tethered adult cattle.

Additionally, we clarified the motivations of tethered adult cattle, which are regarded as having lower motivation for exercise than calves. In the experiment, three cows showed no jumping or running when released to the paddock after restraint for any tethering period. These individuals might not have accumulated behavioural needs for jumping and running behaviour. Actually, these three cows expressing no locomotor behaviour were of the same experimental group. Compatibility among individuals might have influenced the expression of these behaviours. Reportedly, locomotor play such as running and jumping in calves is expressed in a social context (Gomendio, 1988). Furthermore, in calves, behaviours are more pronounced when released

to the play area in pairs than when released alone (Jensen, 2001). Even in adult animals, factors affecting motivation for locomotor behaviour were not clear, but social factors might be related.

Results of this study present the possibility that tethering fosters accumulation of behavioural needs by restraining adult cattle behaviour. Therefore, the welfare of tethered cattle is enhanced when they are released regularly to a play area, which eliminates the accumulation of behavioural needs, although it remains unknown how long a period of tethering increases their behavioural needs.

References

Dellmeier GR, Friend TH and Gbur EE. 1985. Comparison of four method of calf confinement II. Behaviour. Journal of Animal Science 60, 1102-1109.

de Passillé AM, Rushen J, Martin F.1995. Interpreting the behaviour of calves in an open-field test: a factor analysis. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 45, 201-213.

Gomendio M. 1988. The development of different types of play in gazelles: implications for the nature and functions of play. Animal Behaviour 36, 825-836.

Higashiyama Y, Narita H, Nashiki M., Kanno T. 2005. Urinary cortisol levels in Japanese Shorthorn cattle before and after the start of a grazing season. Asian–Australasian Journal of Animal Science 18, 1430-1434.

Higashiyama Y, Nashiki M., Kawasaki M. 2007. A brief report on effects of transfer from outdoor grazing to indoor tethering and back on urinary cortisol and behaviour in dairy cattle. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 102, 119-123.

Jensen MB. 1999. Effect of confinement on rebounds of locomotor behavior of calves and heifers, and the spatial preferences of calves. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 62, 43-56. Jensen MB. 2001. A note on the effect of

isolation during testing and length of previous confinement on locomotor behavior during open-field test in dairy calves. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 70, 309-315

Jensen P, Toates FM. 1993. Who needs ‘behavioural needs’? Motivational aspects of the need of animals. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 37, 161-181.

National Agriculture and Feed Research Organization. 2008. Japanese Feeding Standard

for Beef cattle.

Redbo I. 1993. Stereotypies and cortisol secretion in heifers subjected to tethering. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 38, 213-225.

Sisto AM, Friend TH. 2001. The effect of confinement on motivation to exercise in young dairy calves. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 73, 83-91.

繋ぎ飼いの成牛における運動場解放時の走る、跳ねる行動を用いた行動欲求の評価

中山ふうこ・二宮 茂 *

岐阜大学大学院応用生物科学研究科、* 岐阜大学応用生物科学部,岐阜県岐阜市 501-1193 *Corresponding author. E-mail address: nino38@gifu-u.ac.jp

要 約 繋ぎ飼いはウシの行動を制限することから動機づけられた行動が発現できないことによりウシのスト レス状態を引き起こす要因となりうる。しかし、どの程度の繋留の連続がストレス状態を引き起こすか は明らかでない。そこで、本研究では繋ぎ飼いのウシを運動場に解放した際にみられる、跳ねる、走る 行動に着目し、これらの行動から、繋ぎ飼いのウシの行動欲求の蓄積開始時期について明らかにするこ とを目的とした。実験は、岐阜大学応用生物科学部附属美濃加茂農場で飼育される黒毛和種繁殖雌牛 16 頭を 4 群に分け、群ごとに試験した。まず、繋ぎ飼いにおいて、毎日 5 h (9:30 ~ 14:30) のみ運動 場へ解放される状態にウシを馴らした (TR)。その後、運動場への解放を 1 日間、6 日間中止する処理 (PR1,PR6) を行った。各処理の終了後にウシを運動場に解放し、運動場解放後 1 時間までの行動をビ デオカメラで撮影し、走る、跳ねる行動の発現頻度を記録した。また、繋留時のウシの行動を CCD カ メラで撮影し、解放時と繋留時に発現した行動のレパートリーを比較した。 跳ねる及び走る行動の平均発現回数 ( 回 / 時 / 頭 ) は、TR で 2.1 ± 1.1 回、PR1 で 5.1 ± 1.7 回、 PR6 で 11.4 ± 3.9 回となり、PR6 は TR より有意に多かった (P < 0.05, Dunnett’s test)。また、解放 時にみられた跳ねる行動、走る行動、模擬性行動は繋留時には観察されず、繋留により完全に制限され た。以上のことから、6 日間の繋留の連続はウシの行動欲求の蓄積を引き起こす可能性が示唆された。 キーワード:ウシ、繋留、行動欲求、跳ねる、走る

Animal Behaviour and Management, 54 (4): 165-172, 2018 (2017.11.5 受付;2018.11.19 受理)