SHIMADA, Shonosuke Undergraduate Student, Meijo University Abstract

One language teaching technique, Corrective Feedback (CF) has been defined as an instructional reaction to learners’ problematic utterances. As plenty of research shows its effectiveness in second language (L2) development, the idea of teaching peer corrective feedback to L2 learners (i.e., CF training) has been considered as a way to expand the students’ learning opportunities. This current study demonstrates how beneficial CF training could be provided to L2 learners. Twenty-four students majoring in Foreign Languages in a private university participated in the study and were divided into two groups: the experimental group with CF training (EX) and the control group without CF training (CO). The students in the EX group went through two stages based on Sato & Lyster’s (2012) study: the modeling stage and the practice stage. The results revealed that the majority of the students in the EX group were successfully able to give CF (i.e., recasts and prompts) to their partner and also properly responded to the CF provided. CF training may have the potential to increase and expand students’ learning opportunities by improving their language awareness when they have peer interactional activity and, thereby, contributing to their L2 development.

1. Introduction

Corrective Feedback (CF) has been defined as an instructional reaction toward learners’ problematic utterances (Lyster & Ranta, 1997). After a number of studies revealed its general effects in second language (L2) development, feedback-related teaching strategies have been employed in a variety of educational settings, including high schools and universities (See, Kumada & Okamura, 2019; Makino, 2019; Masumi & Ishikawa, 2016; Oba, 2015). Furthermore, by training students to give peer corrective feedback (PCF), they gain more learning opportunities where they can enhance both internal and external monitoring (Sato & Ballinger, 2012). The current study introduces how effective CF training could improve second language awareness for students who provide CF when speaking the L2 with one another. It also suggests CF training for L2 learners in peer activities as a potentially effective method for L2 teaching.

2. Previous Studies 2.1 Corrective Feedback

Numerous studies on oral and written corrective feedback have been conducted to see how it can be conducive to second language acquisition in a variety of learning

settings, including laboratories and classrooms. CF is considered to be effective in language acquisition (Lyster et al., 2013). There are mainly two types of CF: recasts and prompts, both of which are considered explicit corrections (Ellis & Sheen, 2006; Ammar & Spada, 2006). Recast is a reformulation of students’ utterances that interlocutors give to them (e.g., S: I goed to school. T: Oh, you went to school.).

Prompts are different from recasts because prompts elicit learners’ correct utterances by providing a solution, not correction (Lyster, 2004). Lyster & Ranta (1997) explain that prompts may take the form of elicitation, metalinguistic feedback, repetition, or clarification requests, and they defined the techniques as follows: elicitation is given by questioning directly, such as “How do we say X in English?” or by giving a moment to complete a teacher’s utterance, sometimes with repetition of a learner’s error (e.g., S: I went to shopping yesterday. T: You went to…). Metalinguistic feedback includes information, comments or questions that elicit learners’ correct forms (e.g., S: I like a apple. T: No, not a apple.). Repetition is provided by repeating the learner’s error with changing intonation, emphasizing the error (e.g., S: I was boring in the class. T: You were boring in the class?). Clarification requests point out that a learner’s utterance has been misunderstood or is problematic by asking questions such as “Pardon?” (e.g., S: She can run more fast than me. T: Pardon?) The effects of CF on a wide range of target forms, such as grammatical forms, pronunciation and pragmatic awareness have been demonstrated by researchers (e.g., Ammar & Spada, 2006; Nipaspong & Chinokul, 2010; Saito & Lyster, 2012; Yang & Lyster, 2010). Therefore, CF is an effective tool for L2 learning development as it allows students to review their errors.

2.2 Peer Corrective Feedback (PCF)

Since teacher CF has been proven effective in L2 learning, researchers have begun to investigate the power of PCF, which is usually given during peer interaction (PI). PCF is different from teacher CF because learners become both providers and receivers of CF (Sato & Lyster, 2012), whereas, in teacher CF, students only play a passive role as feedback receivers (Sippel & Jackson, 2015). Therefore, in PCF, students have to pay attention to their partners’ errors as a provider and consider their feedback as a receiver. In other words, by seeking to detect partners erroneous utterances in order to provide CF while also attending to their own utterances, the use of PCF in conversational contexts can improve both external and internal monitoring (Sato & Ballinger, 2012). Moreover, Sato and Lyster (2007) revealed that students felt less pressured and perceived a learner-learner dyad as a non-threatening environment, unlike when they have a conversation in

a native speaker-learner dyad. Furthermore, in a learner-learner dyad, students felt more comfortable asking questions of their partners, so PI may serve to expand learners’ learning opportunities. L2 learners usually have a positive impression of being corrected by their peers (Sato, 2013; Sakiroglu, 2020).

Empirical evidence emphasized the importance of the learners’ mindset and the relationship between partners during PI. It would be best for learners to build a collaborative learning setting and relationship (Sato, 2013; 2017). Sato and Ballinger (2012) also mentioned that without trust and respect for one another, PCF may cause conflict, and learners may lose their learning opportunities. Storch (2002) introduced two distinct patterns of learner interaction: collaborative and expert/novice. These patterns seem to be ideal for PI that contributes to L2 development because collaborative pairs are willing to attend to the task given and the expert in a pair can support the novice. Furthermore, the researcher found that scaffolding is more likely to happen in these two interactional patterns.

Despite the fact that the students’ mindset should be collaborative, when PCF treatment is adopted, they may feel awkward pointing out partners’ errors (Sato & Lyster, 2012), or they may think PCF is less helpful than teacher CF (Sippel & Jackson, 2015). They may even see themselves as incompetent when they make mistakes during peer interaction (Foster, 1998). Learners will truly gain the PI and PCF benefits when they overcome such interactional hurdles, “including mistrust in each other’s linguistic ability and hesitation in providing CF due to their own L2 knowledge (Sato, 2013, p.614)”. In order to deal with social barriers, teachers have to make efforts to design classroom environments that are collaborative (Sato, 2017). They should also be aware that students wish to be corrected by teachers than they want to provide CF (Lyster et al., 2013; Sato, 2013). Therefore, teachers should encourage students to provide CF as much as possible, and with as much trust and respect as teachers do.

2.3 CF Training

Some researchers (Sato & Lyster, 2012; Sippel & Jackson, 2015) showed positive effects of PCF in helping L2 learning development, and that can be as effective as teacher CF. However, in order for PCF to work effectively, students must know how to provide CF properly, and teachers must give lessons that make it possible for students to do so.

Sato & Lyster’s (2012) study investigated whether teaching how to provide CF to L2 learners affects L2 development. The instruction happened in three stages as follows: “modeling, practice, and use-in-context” (p. 601). In the modeling stage, students

watched a mini role-play to ensure that they understood CF moves. In the practice stage, each participant in a group of three had the role of either speaker, feedback provider, or observer, and they switched roles after the end of their turn. Participants were asked to create an original story, and they had to include errors on purpose. When the speaker was telling stories, the feedback provider noticed the errors and gave CF. In the meantime, the observer noted which errors were pointed out and which ignored, giving a report to the group afterward. In the use-in-context stage, students were encouraged to use CF in the “Peer Interaction Instruction” (p. 600). Students were asked to tell their partners about what the previous partner had talked about.

Overall, CF training provided students with additional chances to receive CF. Additionally, Sato and Ballinger (2012) mentioned that teaching CF enhances learners’ language awareness during the instruction, and both CF providers and receivers learn by noticing or monitoring their utterances. Sippel and Jackson (2015) also conducted research to reveal the effects of PCF compared to teacher CF on grammatical accuracy in learners of German. Participants were divided into three groups: a teacher feedback group, a peer feedback group, and a control group. In the peer feedback group, participants were taught how to provide CF to their partners. The results revealed that both the teacher and the peer feedback groups had a positive impact, with PCF providing equal or greater benefits than teacher CF. This might be because the learners’ role in the teacher feedback group was only that of a CF receiver, whereas the learners in the peer feedback group were both providers and receivers of CF. In this study, other factors, such as “self-corrections and group discussions about linguistic forms” (p. 700) may trigger the learners’ gains. From the previous studies mentioned above, CF training is worth conducting for students to lead peer feedback; that is, in a peer activity.

2.4 The Purpose of the Current Study

For this study to test CF training, it had to be properly taught to students. This was done based on Sato & Lyster’s (2012) training framework. Only a few studies have investigated the effects of CF training and PCF on L2 learners (e.g., Sato & Lyster, 2012), despite the promising results. To teach CF properly to students, a CF training framework, based on Sato & Lyster’s (2012), was implemented in this study in order to see if CF training in the current study works well. Students were divided into two groups: the EX group provided with CF training and the CO group without CF training. Students in the EX group went through two stages, the modeling and practice stages, during the intervention. Prompts were taught because of their positive effect on L2 development

(Lyster et al, 2013), and because they were more favored by students than recasts in terms of their effectiveness for language development (Sato, 2013). Comparing the usability of recasts and prompts, the latter are probably easier to use for learners because recasts are more commonly provided by people with high proficiency in the language, such as teachers and NSs (Ammar & Spada, 2007; Sato & Lyster, 2007).

Thus, this study investigates how CF training can contribute to improving students’ CF production during PI. The research questions are as follows:

1. Does explicitly training students in CF increase the amount of CF they provide during peer interaction?

2. What are the different types of CF these students provide and to what extent is each type provided during peer interaction?

3. Methods 3.1 Participants

Twenty-eight third year university students were supposed to participate in the study. However, five of them were not able to participate due to unforeseen events. In the end, 24 participants (23 third year and one fourth year university student), who were majoring in Foreign Languages at a private university, joined the study. Each participant completed a consent form about the use of their information. All of them had been taking English as a Foreign Language (EFL) classes (e.g., Communication, Discussion) and other English-related classes (e.g., Syntax, Phonetics).

They were divided into two groups according to their TOEIC scores: an experimental (EX) group (n = 12), whose average score was 674.58, with a range of 500 to 865, and a control (CO) group (n = 12), whose average score was 656.25, with a range of 445 to 825. Each of the pairs in both of the groups was designed to be a high-low English proficiency dyad because such a dyad is more likely to benefit from peer interactional activity than other dyads (Storch, 2002). The average high and low scores of the EX and CO groups as follows: in the EX group, the high was 755.83, and the low was 593.33 while the high was 761.00 and low was 575.83 in the CO group. Therefore, in each group, one participant with a lower score and one with a higher score were paired together. The average scores of each pair were roughly equivalent.

3.2 Materials

3.2.1 Pre- and posttests

There were four pictures in total (extracted from Obunsha, 2009) (two pictures for each pre- and posttest) depicting one story with a two or three sentence introduction. The pictures used in the pre- and posttests were different. The EX and CO groups were examined to see whether they produced CF. In either the pretest or posttest, the speaker was asked to make an original story based on the provided picture. The listening student was not instructed to provide CF, but only give advice and suggestions that made the story better. Both tests were conducted in turn.

3.2.2 CF training videos

For the CF training given to the EX group, demonstration videos were made and shown that explained how peer CF was conducted in a pair. In the videos, two male students performed as teachers. They were Japanese fourth year university students with high English proficiency (one, the author, had scored 7.0 overall on the IELTS, and the other had completed EIKEN Grade Pre-1, had scored 875 on the TOEIC, and had lived in Canada for two years in total). In the videos, one teacher described a picture. While listening, the other teacher provided prompts to help the partner correct his errors. Scripts were given to the EX group to make sure the content was fully understood. All of the CF appeared in the scripts in boldface and was underlined, and also the name of the CF technique was written next to the CF in parentheses. All erroneous utterances were in boldface followed by the correct grammar in parentheses. The teachers played both the speaker and the listener. Here is an example of the video scripts.

A. One day, Tomoko went shopping at a supermarket with her father. When they check (checked) their groceries.

B. What did you say? (clarification requests)

A. I mean when they checked (repair) their groceries, a clerk was giving a plastic bag to pack them. However, Tomoko’s father said “I have my own shopping bag.” and refused receiving the bag.

A. Then he gives (gave) a card to the clerk. B. He gives a card to the clerk. (repetition)

A. Yes, he gave (repair) a card to him. Seeing the card, Tomoko was wondering what it was. An hour later, his father explained to Tomoko about what was happening. He showed the card and said “every time you refuse a plastic bag, you can get one seal on your shopping coupon. When you get 15 seals in total, you are going to get a present.” Tomoko thought that is (was) a great idea.

B. Pardon? (clarification requests)

A. Tomoko thought that was (repair) a great idea. So, a few days later, she started to collect the seals.

3.2.3 CF training Tasks

In the modeling stage, the EX group was given a lecture by the author, mainly in Japanese and partially in English and was shown the short role play video described above. The lecture explained CF and the types of CF (i.e., recasts and prompts), showing some example sentences. At the end of the modeling stage, the lecturer emphatically told the students about the important keys that make CF training succeed, as suggested by Sato and Lyster (2012): “(a) autonomous attention to linguistic forms, (b) quantity and quality in feedback, and (c) positive perceptions of PI belief” (p. 598). However, it was requested that they seek feedback quantity rather than quality because the CF technique was a novel learning strategy for the participants. If they focused on quality, the CF training would be much more challenging for them.

In the practice stage, three tasks were provided to the EX group to train them to use CF. The three tasks were based on the same book (Obunsha, 2009) as the pre- and posttests. In all of the tasks, participants in pairs played the role of either speaker or listener. The role of ‘observer’ as shown in Sato & Lyster’s (2012) study was excluded in this study because it sought to confirm whether the participants could detect their errors and provide CF by themselves. In Task 1, each participant was given one story with four errors written on each side of the handout. In a pair, the speaker read the one story, while the listener tried to provide CF while looking at the same story written.

In Task 2, each of them was asked to make an original story based on a given picture, and to tell the story to their partner. The speakers were told to include errors in their stories intentionally. Therefore, listeners attempted to notice the errors and to provide appropriate CF. Every picture shown in Task 1 and 2 was different.

In Task 3, each pair of participants simply had a conversation about a given topic with each other for three minutes. (i.e., What is your best memory from high school or university?) However, participants were told to give CF when they noticed problematic utterances. The three tasks provided appropriate training in CF to the EX group.

3.2.4 A Netflix Video

For the CO group, after the pretest, they watched a Netflix video, which was not related to CF or any English materials for 30 minutes, this was an equivalent amount of

time to the period of CF training provided the EX group. 3.3 Procedures

The EX group was divided into six pairs (high-low English proficiency dyads). Each pair had the pre/posttests and the three training tasks in its own room. One examiner observed the whole treatment and recorded it with a video camera for the purpose of analyzing the utterances. The six pairs were tested and practiced CF in six different rooms. For the CF lectures, all participants in the EX group gathered in a room to watch the CF video and the lecture. The process for the EX group was as follows: the pretest, the lecture and the CF video, the three CF tasks, the posttest, the exit questionnaire.

The CO group was divided into six pairs (high-low English proficiency dyads). The procedure was the same as the EX group, but a Netflix video was used instead of the CF training intervention. Figure 1 shows an outline of the experiment for the EX and CO groups.

Figure 1

4. Results

4.1 The Amount of CF Provided

In order to address research question 1 and to assess the effects of the CF training, the mean scores and standard deviations of the amount of CF occurring in the pre- and posttests between the EX group and the CO group are shown in Table 1. In the pre- and posttests, occurrences of CF in the transcription of the utterances of each pair were counted. One instance of CF was counted as one point. Here is an example of the feedback. Student 1: Several months later, he, she thinks, how to, how to…, Student 2: how to cultivate maybe. This feedback was considered to be recast.

As Table 1 depicts, the EX group increased the mean scores of CF provided from 0.00 in the pretest from 1.67 in the posttest while the CO group did not show any increase. This suggests that the CF training may improve learnres7 ability to provide CF. Therefore, the first research question, “Does explicitly training students in CF increase the amount of CF they provide during peer interaction?” was positively answered.

Table 1

The Amount of CF Provided by the Participants

Group (n) Pretest Posttest M SD M SD

EX (12) 0.00 0.00 1.67 1.78

CO (12) 0.17 0.39 0.00 0.00

4.2 Types and Distribution of CF

As for the second research question regarding what types of CF occurred in the EX group after the CF training, the following sentences are examples of utterances taken from the transcripts showing the possible types of CF.

(1) Y: She wanted? She want to him to get a mail... quickly. S: Quickly? (repetition)

Y: Quickly? As soon as possible?

T: No, no you should past tense. (metalinguistic feedback) M: They found a house.

(3) Y: And she decided to send a mail through computer. N: Yeah, it’s email. (recast)

Y: Yeah, email.

(4)Y: So, she changed the way to send a mail to her friend. S: A mail? Which mail? The mail? (elicitation)

Y: A letter. The letter.

(5) M: A few days later, she can’t finish the, finish T: What, What? (clarification requests)

M: She couldn’t, she couldn’t finish writing email.

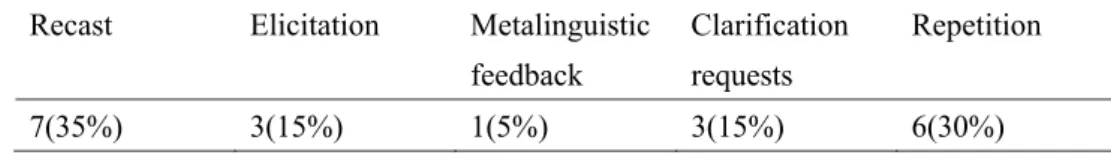

Table 2 presents the types of CF techniques and their distribution during the posttest as provided by the participants who received CF training1. The results suggest that recast

was the CF technique most favored by them, despite the fact that it had not been taught to them. Repetition was the second most favored technique (30%). Clarification requests (15%) and elicitation (15%) were used with the same frequency, but not as frequently as the two techniques above. Metalinguistic feedback (5%) was used with the lowest frequency.

Table 2

The Types and the Distribution of CF Provided by the Students

Recast Elicitation Metalinguistic

feedback Clarification requests Repetition 7(35%) 3(15%) 1(5%) 3(15%) 6(30%) 5. Discussion

The results of this study suggest that explicit CF training can increase students deliberate use of CF techniques. The results were consistent with those of Sato & Lyster’s (2012) study, which showed that students who had CF training produced more CF than those in the CO group. Despite the fact that they were only told to “give advice and

suggestions that make the story better” in both the pretest and posttest, they provided CF in the posttest. In the pretest, they did not provide CF but added positive comments or questions about their partner’s story (e.g., I think that was a good story.). Therefore, it suggests that CF training can be effective for increasing CF production.

One of the critical factors that enabled students to provide CF was the relationships between students (Sato & Ballinger, 2012; Sato, 2013; 2017). In this study, each pair consisted of students who had low and high proficiency in English. Five out of six pairs increased the provision of CF. The high proficiency learners in those five pairs were able to provide correct CF. The relationships mirrored Storch’s (2002) one of the two ideal dyads which were shown to be conducive to L2 development; expert/novice. Such student of pairs might produce well-functioning PI (i.e., CF training) and, therefore, they could learn use of CF methods in the experiment.

There were some exceptional students who did not provide CF to their partners. One of the students told her partner when she was a CF provider, “The story was perfect to me. Were you aware of any errors that you made?” She thought that her partner had made no mistakes, but, in fact, he had four errors in his story. It is clear that learners could not provide CF when they could not detect any errors, even if they had paid attention to their peer’s utterances. Another student was paired with a senior student. In the dyad, she had to interact with a senior student who she had never talked with before. Therefore, there might have been social obstacles (Sato, 2013). The CF training employed in this study positively contributed to CF production, with the exception of those pairs that did not have a strong relationship.

To answer the second research question, students’ CF production showed that recast was the feedback technique most frequently used by the students, even though they had been taught how to provide prompts, not recasts. This might be because the EX group participants categorized as having high English proficiency were relatively proficient. They had a mean TOEIC score of 761, with the range going from 675 to 865. According to a report of the Institute for International Business Communication (2020), the mean score of English-major students who were in third year in university was 564. Comparing these scores, the participants in this study had higher proficiency. Therefore, they preferred to use recasts because they were able to guess what their partners who had lower English proficiency wanted to say (Sato & Lyster, 2007). Also, recasts are likely to occur when grammatical errors are produced (Lyster, 1998). Therefore, students might able to give recasts without actually understanding the idea of recasts. Repetition was revealed to be the second most preferred CF technique. This preference might be because repetition

was easier for learners to give, just requiring them to repeat errors with adjusted intonation (Lyster & Ranta, 1997).

Regarding the amount of CF produced by the students who had CF training, the method of teaching CF to L2 learners in the current study appears to have been effective. One important factor in the success of the CF training appears to have been the paring of students into high/low English proficiency dyads. Overall, the higher proficiency learners were able to rely on their grammatical knowledge for spontaneous oral production (Sato & Lyster, 2012), so language ability might be vital to the success of CF training. Depending on whom students are partnered with (Storch, 2002), the effectiveness of CF training might be greatly highlighted.

Students’ social relationship might be another a key factor in the success of CF training. Therefore, CF accuracy would be improved by conducting long-term interventions in well-planned classes (Sato & Ballinger, 2012, Sippel & Jackson, 2015), so that students become able to utilize CF techniques in the context of established relationships.

6. Implication of English Education

Considering the effects of PCF and its ability to improve learners’ language awareness and contribute to L2 learning, this type of CF training could be conducive to L2 language learning development and could be applied to classroom lessons. However, PCF is related to the relationship between learners. Teachers need to build a collaborative classroom environment (Sato & Ballinger, 2012; Sato, 2017) and discipline themselves to avoid over-monitoring PI so that they can see students’ efforts (Sato, 2017). Teachers play an important role in making PCF effective, so they have to be careful about how they intervene in PI.

7. Conclusions

This paper examined the effectiveness of explicit CF training, which trains learners to be CF providers and receivers during PI. The results revealed that students who were taught how to give CF successfully provided various kinds of CF to their partners. Providing CF training to students (i.e., a lecture and three tasks to practice) caused them to pay much more attention to their partners’ and their own utterances than they had previously.

There are some limitations to this study. First of all, the sample size (N = 23) was quite small, so similar experiments with more participants are needed to confirm the results of the current study. Another limitation is the short duration of the study. CF training usually takes a long time in order to offer plenty of opportunities for students to understand and practice CF skills so that they can use them properly. Future research needs to be conducted over a longer term and with more participants. Moreover, experiments in CF training should be conducted in classroom settings to evaluate whether they are effective with students having a high school or junior high school level of English. Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my supervisor, Yuri Nishio, whose instruction was far more than helpful throughout the paper writing. Your feedback always deepened my thinking and made my paper much better.

Notes

1. The total number of CF occurrences in the posttest was 20.

Some parts of this paper were given as an oral presentation at the JACET 35th Chubu Chapter Annual Convention (September 12, 2020).

References

Alsolami, R. (2019). Effect of oral corrective feedback on language skills. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 9(6), 672–677. http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0906.09

Ammar, A., & Spada, N. (2006). One size fits all?: Recasts, prompts, and L2 learning. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 28(4), 543–574. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0272263106060268 Ellis, R., & Sheen, Y. (2006). Reexamining the role of recasts in second language acquisition. Studies

in Second Language Acquisition, 28(4), 575–600. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/ S027226310606027X

Foster, P. (1998). A classroom perspective on the negotiation of meaning. Applied Linguistics, 14(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/19.1.1

Kumada, M., & Okamura, T. (2019). A survey on "Students' self-esteem improvement through class cooperation experiences" in English conversation classes: Focus on internal factors of learners. Bulletin of Nara Gakuen University, 10, 55–61. http://id.nii.ac.jp/1413/00003096/

learner repair in immersion classrooms. Language Learning, 48(2), 183–218. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/1467-9922.00039

Lyster, R. (2004). Differential effects of prompts and recasts in Form-Focused Instruction. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 26(3), 399–432. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263104263021 Lyster, R., & Ranta, L. (1997). Corrective feedback and learner uptake: Negotiation of form in

communicative classrooms. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 19(1), 37–66. https:// www.jstor.org/stable/44488666

Lyster, R., Saito, K., & Sato, M. (2013). Oral corrective feedback in second language classrooms. Language Teaching, 46(1), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444812000365

Makino, M. (2019). Eigo rimediaru jugyo niokeru piafi-dobakkukatudo wo toriireta supi-chi tore-ninngu no jissennhokoku [Speech training with peer feedback activity on a remedial education]. Journal of the Japan Association for Developmental Education. 13, 43–50. https://doi.org/ 10.18950/jade.2019.02.06.01

Masumi, A., & Ishikawa, S. (2016). Nihonjinkokosei no L2 eigohatiwa no ryutyosei wo takameru fi-dobakku no arikata - jikohyoka piahyoka shidoshahyoka no yukosei no kennshou [The role of feedback that enables Japanese high school students to improve their English fluency: Investigating the effects of self-evaluation, peer-evaluation or teacher-evaluation]. Journal of the School of Languages and Communication Kobe University. 13, 76–89. https://doi.org/ 10.24546/81009749

Nipaspong, P., & Chinokul, S. (2010). The role of prompts and explicit feedback in raising EFL learners' pragmatic awareness. University of Sydney Papers in TESOL, 5, 5. https://

faculty.edfac.usyd.edu.au/projects/usp_in_tesol/pdf/volume05/Article04.pdf

Oba, H. (2015). Kyodogakushu ni motoduku eigo komyunike-shonkatudo ga eigogakushuiyoku ya taido ni oyobosu eikyo: tekisuto maininngu niyoru bunnseki [The effects of English communication based on cooperative learning that influences students' learning attitude: Text-mining analyses]. Bulletin of Joetsu University of Education, 34, 177–86. http://hdl.handle.net/ 10513/2792

Obunsha. (2009). Daily 10nichikann eiken 2 kyu nijisikenn taisaku yoso monndai [The ten-day drill book for the STEP Test in Practical English Proficiency]. Obunsha.

Saito, K., & Lyster, R. (2012). Effects of form-focused instruction and corrective feedback on L2 pronunciation development of /ɹ/ by Japanese learners of English. Language Learning, 62(2), 595–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2011.00639.x

Sakiroglu, H. Ü. (2020). Oral corrective feedback preferences of university students in English communication classes. International Journal of Research in Education and Science, 6(1), 172– 178. https://doi.org/10.46328/ijres.v6i1.806

Sato, M., & Ballinger, S. (2012). Raising language awareness in peer interaction: A cross-context, cross-method examination. Language Awareness, 21(1-2), 157–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 09658416.2011.639884

Sato, M., & Lyster, R. (2007). Modified output of Japanese EFL learners: Variable effects of interlocutor vs. feedback types. In A. Mackey (Ed.), Conversational interaction in second language acquisition: A collection of empirical studies. (pp. 123–142). Oxford.

Sato, M., & Lyster, R. (2012). Peer interaction and corrective feedback for accuracy and uency development: Monitoring, practice, and proceduralization. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 34(4), 591–626. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263112000356

Sato, M. (2013). Beliefs about peer interaction and peer corrective feedback: Efficacy of classroom intervention. The Modern Language Journal, 97(3), 611–633. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2013.12035.x

Sato, M. (2017). Oral peer corrective feedback: Multiple theoretical perspectives. In H. Nassaji & E. Kartchava (Eds.), Corrective feedback in second language teaching and learning. (pp. 19–34). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315621432

Sippel, L., & Jackson, C. N. (2015). Teacher vs. peer oral corrective feedback in the German language classroom. Foreign Language Annals, 48(4), 688–705. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12164 Storch, N. (2002). Patterns of interaction in ESL pair work. Language Learning, 52(1), 119–158.

https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9922.00179

The Institute for International Business Communication. (2020). TOEIC Program DATA & ANALYSIS 2020. https://www.iibc-global.org/library/default/toeic/official_data/pdf/DAA.pdf Yang, Y., & Lyster, R. (2010). Effects of form-focused practice and feedback on Chinese EFL learners’

acquisition of regular and irregular past-tense forms. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 32(2), 235–263. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263109990519