奈良教育大学学術リポジトリNEAR

Types of Communication Strategies Used by Japanese Learners of English

著者 WATANABE Kazuo, GAPPA Akira journal or

publication title

教育実践総合センター研究紀要

volume 13

page range 33‑39

year 2004‑03‑31

URL http://hdl.handle.net/10105/112

1.Introduction

The world has become smaller and smaller with improvements in technology such as computers and mobile phones. People increasingly have more opportunities to communicate with people from dif- ferent backgrounds. This does not necessarily mean that communication takes place without challenge.

In fact, difficulties are often encountered in commu- nicating in English, particularly with non-native speakers of Japanese. For example, it has been pointed out that some Japanese can translate long and complicated English passages into Japanese, but have more difficulties in using English for conversa- tional purposes. Because of this gap, frustration is a likely outcome, which, in turn, may adversely affect motivation toward learning English. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate why this gap exists despite

the fact that most Japanese have studied English for a considerable amount of time.

A number of reasons are considered the source of this problem. Some people say that Japanese learners of English are not confident enough to speak English because they lack practice in speak- ing. Others argue that the problem lies in poor lis- tening comprehension skills. Because Japanese learners of English cannot understand what their partners say, they have no idea of how to react ver- bally. Few would argue with these points.

However, it is important to remember that even when people speak their native language, they sometimes have difficulties in communicating with others. It follows, then, that the communication problem cannot originate entirely from lack of lin- guistic proficiency. How does a speaker manage the situation? The solution may lie in whether or not the speaker can make good use of communication strategies (CS) in interaction with the listener. It is

Used by Japanese Learners of English

WATANABE Kazuo and GAPPA Akira*

(Department of English Education, Nara University of Education, Nara 630-8528, Japan)

Abstract

Research on communication strategies (CS) has been conducted for the past few decades. Iwai (1995, 2000) and Chen (1990), for example, worked on the relationship between linguistic proficiency and CS choice. Bongaerts and Poulisse (1989) and Iwai (1995, 2000) investigated CS of subjects' first language (L1) and their second language (L2). Nakano (1996) and Bongaerts and Poulisse (1989) researched into tasks and CS choice. Since the researchers have not reached a legitimate conclusion yet, the following research questions (RQ) have been addressed: RQ1.

Will a high level English proficiency (HE) group tend to use the same strategies in English as they do in Japanese more frequently than a middle level English proficiency (ME) group or a low level English proficiency (LE) group? RQ2. Will an LE group tend to use more Conceptual Holistic (HOCOs) in English description of objects than other groups do? RQ3. Will an LE group use more HOCOs than other groups do in English? Thirty people who had been learning English conversation once a week participated in this study. The research questions were rejected statistically; however, two interesting tendencies were discovered: the ME and LE groups had a tendency to rely more on HOCOs in English than in Japanese, and the total number of Conceptutal Analytic (ANCOs) the LE group used in English was much smaller than in Japanese. These tendencies seem to imply that linguistic proficiency may influence CS choice.

Key Words: communication strategies, Japanese learners of English, picture description

*Konan University(part time)

assumed here that if Japanese learners of English know how to use CS well, they may have greater opportunities to improve their speaking skills because they might avoid falling into silence during the conversation. If so, this may lead to a more positive attitude toward communicating in English.

2.Previous Studies

Language learning researchers may have heard of "CS", and may even have had opportunities to find the term in both articles and books on how to improve speaking skills. Caution is necessary, how- ever, for it is used differently, depending upon the author's conception of the term. Here is one of the most frequently used definitions:

strategies which a language user employs in order to achieve his intended meaning on becoming aware of problems arising during the planning phase of an utterance due to his own linguistic shortcomings (Poulisse et al., 1990, p.22).

Having introduced a major definition of the term, it is also necessary to recognize the typology of CS. The following is Poulisse et al.'s (1990) typolo- gy:

Conceptual 1.Analytic (ANCO) 2.Holistic (HOCO) Linguistic 1.Transfer (LITRA)

2.Morphological Creativity (LIMO)

As seen above, this typology is lucid and con- crete. In Nakano (1996), examples of ANCO, HOCO, LITRA, and LIMO are presented. If a speaker says

"… this is living… in the sea" to describe "squid" or "

… violet vegetable" to explain "eggplant", it is ANCO. On the other hand, "hat" for a stocking cap or "food" for "vegetable" is HOCO. If a speaker does not know the word "dice" and says "saikoro" in Japanese, it is LITRA. LIMO is the case where an inappropriate expression, but an unique coinage

"tenpus" is ventured for "squid".

Iwai (1995, 2000) looked at the relationship between linguistic proficiency and CS choice in the learner s first language (L1) and his/her second lan- guage (L2). Thirty-two college students participated

in this study, and were divided into two groups, which were a high level English proficiency (HE) group and a low level English proficiency (LE) group according to TOEIC (Test of English for International Communication) scores administered in May, 1994. First, they were asked to describe nine abstract pictures in Japanese. The pictures were the same used in Bongaerts and Poulisse (1989).

Three of the pictures were distractors, and six pic- tures were used for the analyses of the study. One week later, subjects were asked to perform the same task in English. All utterances were recorded and transcribed. Since it was a follow-up study on such the Nijmegen projects in Netherlands as Bongaerts and Poulisse (1989) and Kellerman et al.

(1990), the typology devised by Kellerman et al. was adopted.

Linear perspectives are used when subjects break a shape up into its ultimate components such as lines and angles. The linear strategy was not included because the rate of occurrence was extremely rare. "H" is a holistic strategy. "HP" is a case where a holistic strategy is used first, and then followed by a partitive strategy, which is the same as ANCO. In this study, the HE group used 4 "H"s, 32 "HP"s, and 38 "P"s, while the LE group used 13

"H"s, 37 "HP"s, and 35 "P"s in their Japanese descrip- tion. On the other hand, in English the HE group used 26, 23, and 31 times, and the LE group 36, 18, and 24 times respectively. No significant differences were observed between the HE and LE groups in either language. From this result, it was concluded that proficiency level did not influence CS choice either in L1 or in L2.

Conflicting results, however, have been record- ed. In Chen (1990) twelve English majors at Guangzhou Foreign Language Institute in China were asked to participate in the study. They were divided into two groups (HE and LE) according to their general English proficiency. Each subject was required to communicate two concrete concepts in English such as monkey and peacock and two abstract ones such as destiny and confidence from the twenty-four words to a native-speaker interlocu- tor in an interview situation.

For the typology, Linguistic−based CS (LB), Knowledge-based CS (KB), Repetition CS (R), Paralinguistic CS (P), and Avoidance CS (A) were adopted. Some of the subjects were quoted as describing "I can say this is the opposite meaning of WATANABE Kazuo and GAPPA Akira

"mean" for "generosity" or "I think it has the same meaning as lobster for "prawn". This is regarded as

"LB". On the other hand, if a speaker describes a concept or an object by exploiting his or her world knowledge by giving examples or providing cultural characteristics, it is considered "KB". For example, one of the subjects expressed, "Perhaps in Beijing, I think in Beijing there are a lot of this fruit" for

"peach". "R" is to repeat what he or she said. One of the examples seen in the study was It s a kind of seafood… It s a kind of seafood. P is when a speaker uses gestures as well as verbal output to convey meaning. If a speaker gives up on a mes- sage after several tries, it is A .

The HE group used 58 "LB"s, 7 "KB"s, 4 "R"s, 3

"P"s, and 0 "A" out of 72 CS. On the other hand, the LE group used 61, 46, 38, 2, and 1 out of 148 CS respectively. A significant difference between the HE and LE groups in the use of CS within "LB",

"KB", and "R" was obtained. The HE group relied more upon "LB", whereas the LE group depended more on "KB" and "R". The reason for this is that the HE group had greater formal control over the target language. As for the LE group, their limited linguistic knowledge prevented them from relying on LB, and they tried to compensate for this by drawing upon their common knowledge, or just repeated the same thing. It was concluded that types of CS vary according to subjects' linguistic proficiency level.

In addition, a controversy has developed regarding CS use between L1 and L2. Bongaerts and Poulisse (1989) show that when speakers are confronted with a communication problem, they overcome it in much the same way regardless of L1 or L2. A total of thirty Dutch secondary school stu- dents (15 junior high school students and 15 high school students) and fifteen Dutch university stu- dents of English participated in this study. They were divided into three groups (advanced, interme- diate, and low) depending on the number of years of their English study. The types of CS used in Dutch were compared with those in English. Subjects used 375 HOCOs (advanced 134, intermediate 124, and low 117) out of 540 protocols in Dutch. On the other hand, they used 372 HOCOs (137, 119, and 116 respectively) in English. A partitive perspective was adopted on 97 occasions (21, 33, and 43 respec- tively) in Dutch and on 87 (21, 34, and 32 respective- ly) in English. Finally, linear perspectives were

taken 67 times (25, 22, and 20) in Dutch, and 78 times (22, 25, and 31) in English. From this result, it was concluded that because the majority of CS were HOCOs in both languages, the same type of CS was used regardless of language.

According to Iwai (1995, 2000), when he looked at the ratios of the same strategies used across lan- guages, of the total 96 protocols dyads in each group (i.e., 16 subjects x 6 pictures), 25 cases (26%) were the same among the HE group, while 23 cases (24%) were the same among the LE group. This result shows that subjects did not often use the same CS in English as they did in Japanese. In addition, the HE group used 4 "H"s in Japanese and 26 "H"s in English. As for the LE group, subjects used 13 "H"s in Japanese and 36 "H"s in English. Therefore, it was concluded that subjects tried to overcome their difficulties by using different types of CS in L2 from those used in L1 regardless of English proficiency.

Further controversy has been noted between the nature of tasks and CS choice. As Nakano (1996) indicates, it is said that ANCOs are used more often in description of objects (picture description). This is perhaps because subjects do not have a conversa- tion partner in the picture description, and they can- not expect any help from the partner. This use of ANCOs tends to make utterances more informative so that the listener may understand them more easi- ly. In the case of Bongaerts and Poulisse's study (1989), they reported that more HOCOs were seen in abstract picture description regardless of English proficiency. Tsuchimochi (2001) also reported the influence of the nature of the tasks on CS choice.

In Nakano (1996), however, nine high school stu- dents in Okayama who were considered weak in English were asked to describe objects in English, and used HOCOs most frequently in the task; that is to say, most of the subjects apparently could not use ANCOs when they wanted to. The reason for this may be due to the subjects' lack of English profi- ciency. Therefore, it was concluded that it is English proficiency rather than the nature of tasks that primarily affects CS choice.

3.Method

3.1.Purpose

The purpose of this study is to investigate how CS are used by Japanese learners of English both in Japanese and English. As it is clear from the previ-

ous studies and Matsumoto (1999), no definitive con- clusion has yet been reached as to what makes learners choose specific CS particularly in L2. To verify the contradictory results from previous stud- ies, the following research questions (RQ) are addressed:

RQ1.Will an HE group tend to use the same strate- gies in English as they do in Japanese more frequently than a middle level English profi- ciency (ME) group or an LE group?

RQ2.Will an LE group tend to use more HOCOs in English picture description than other groups do?

RQ3.Will an LE group use more HOCOs than other groups do in English?

3.2.Subjects

The total number of subjects in the present study is thirty people who had been learning English conversation once a week at a private English conversation school in Osaka, the period of their study ranging from a few to twenty years.

The data were collected in the summer of 2001. To divide them into three groups (HE, ME, and LE), an informal version of TOEIC was given to the sub- jects. This test was adopted for the present study due to the recognition that it is designed to measure a learner's communication ability in English rather than grammatical knowledge alone. Subjects who received 50 to 70 correct answers out of 200 were put in the LE group, 88 to 108 in the ME group, and 120 to 152 in the HE group. There were ten people in each group. The subjects in the HE group includ- ed one man and nine women. All were adults, and the average age was 30.5 years old. In the case of the ME group, all were women over twenty except for one high school girl, and the average age was 34.5 years old. The LE group consisted of adults only: one man and nine women. Their average age was 38.5 years old. For further confirmation of this group division, subjects were also required to fill in a questionnaire about their English learning back- ground. This addressed the period of English con- versation study, kinds of authorized English tests taken before, and experience(s) in traveling abroad.

(Appendix A)

3.3.Data Collection Procedure

In the present study, Poulisse's (1990) typology is followed, as most of the researchers examined here have adopted Poulisse's (1990) typology for their own studies, and the results of their studies should be further pursued.

Pictures used in this study were the same as those used in Nakano (1996). (Figure 1) A pair of two picture description tasks in two languages (i.e., Japanese and English) was given at an interval of one week. Those two pictures were randomly cho- sen for each subject from a total of nine. After the first picture was finished, the second one was given.

The subject had one minute to organize his/her thoughts, and the time allowed for the description of each picture was limited to a maximum of two min- utes for both languages.

In addition, a story-telling task using a comic strip was administered. (Figure 2) The comic strip was from Heaton (1975). Subjects had three minutes to prepare for the task before a maximum of four minutes was given to tell the story first in Japanese and a week later in English. They were told to make a story about the comic strip so that anyone could vividly imagine what they were trying to say.

Only one subject and the experimenter were in the room. A retrospective interview was conducted after each subject finished his/her task in both lan- guages.

WATANABE Kazuo and GAPPA Akira

Figure 1

Figure 2

4.Results and Discussion

To examine the RQ1, the number of the same CS in both languages was counted and summarized in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 The Number of the Same CS across the Languages

The equal sign indicates the same CS.

See Table 3.1 for the total number of CS subjects used in Japanese.

As Tables 1.1 and 3.1 show, 19 cases out of 64 (30%) in the HE group, 19 cases out of 51 (37%) in the ME group, and 20 cases out of 54 (37%) in the LE group were the same CS across the two lan- guage sessions. From this data, no statistically sig- nificant difference was obtained among the three groups. The result shows that the same CS were used less frequently across the languages regardless of their English proficiency. Furthermore, as Tables 3.1 and 3.2 show, 54 HOCOs (HE 26, ME 14, and LE 14) were used in Japanese. On the other hand, 100 HOCOs (HE 30, ME 36, and LE 34) were used in English. The results show that subjects, particular- ly the ME and LE groups, relied more on HOCOs in English. Therefore, the RQ1 has been answered negatively. The results support Iwai (1995, 2000) who concluded that subjects tried to overcome their difficulties by using different types of CS in L2 from those used in L1 regardless of their English profi- ciency.

Table 2.1 The Number of CS Used in Picture Description in Japanese

Table 2.2 The Number of CS Used in Picture Description in English

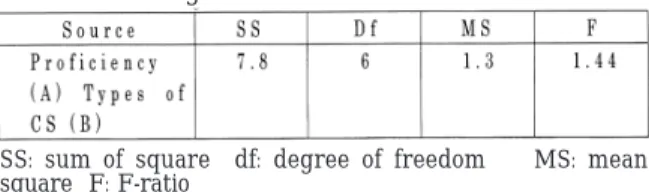

Table 2.3 Results of ANOVA for Picture Description in English

SS: sum of square df: degree of freedom MS: mean square F: F-ratio

As indicated in Table 2.3, the RQ2 has also been rejected. According to Tables 2.1 and 2.2, however, the result does not necessarily support Bongaerts and Poulisse (1989) or Tsuchimochi (2001) because both HOCOs and ANCOs were used in picture description in Japanese or in English. The number of HOCOs the HE group used slightly decreased in English compared with that in Japanese; on the other hand, in the case of the ME and LE groups, the number of HOCOs noticeably increased in English, as in Tables 2.1 and 2.2. This result implies that the ME and LE groups had a tendency to rely on HOCOs in English picture description, perhaps because they are regarded as less energy-consum- ing. Therefore, Nakano (1996) and the RQ2 cannot be completely rejected.

Finally, to answer the RQ3, the total number of CS used both in Japanese and English was counted and compared.

Table 3.1 The Total Number of CS Used in Japanese

Table 3.2 The Total Number of CS Used in English

Table 3.3 Results of ANOVA for Japanese Tasks

Table 3.4 Results of ANOVA for English Tasks

As Table 3.3 shows, there is no relationship between subjects' English proficiency and types of CS used in Japanese. This result is not surprising because the study was conducted on the assumption that Japanese linguistic proficiency, regardless of English proficiency, would not differ greatly. As shown in Table 3.4, the relationship between English proficiency and CS used within the English versions revealed no significant differences, either.

Therefore, the RQ3 has also been rejected. This finding is analogous to the results obtained in Iwai (1995, 2000).

Despite the fact that the RQ3 has been rejected statistically, it was observed that the number of HOCOs the ME and LE groups used for English tasks increased sharply according to Tables 3.1 and 3.2. This was probably caused by their reliance on HOCOs due to a lack of linguistic proficiency. This result is the same as pointed out above, and it tends to support Chen (1990). In addition, while the number of HOCOs in English in both the ME and LE groups increased, the number of ANCOs the LE group used in English decreased sharply as shown in Tables 3.1 and 3.2. This result also lends support to Chen (1990). From these two results, we might point out that the possibility that linguistic proficien- cy could influence CS choice cannot be excluded.

.

5.Conclusion

This study has attempted to investigate the research questions based on three relationships:

Japanese learners' English proficiency and types of CS used; types of CS and the nature of the tasks; CS in L1 and L2. All the three research questions were rejected statistically, which leads to support Iwai (1995, 2000) on English proficiency and types of CS used, and on CS in L1 and L2.

While the research questions have been reject- ed according to statistical analysis, two interesting observations with regard to the RQ2 and RQ3 can be made. First, when the number of HOCOs used in Japanese and in English was compared, the HE group used only four more HOCOs in English than in Japanese (Tables 3.1 and 3.2). On the other hand, the number of HOCOs used by the ME and LE groups was much larger in English than in Japanese (Tables 2.1, 2.2, 3.1, and 3.2). This result indicates that due to a lack of ability in English the ME and LE groups had a tendency to rely more on HOCOs,

which are considered to be less energy-consuming than ANCOs; this could indirectly lend affirmative support to the RQ2 and RQ3. Second, the LE group used far fewer ANCOs in English than in Japanese according to Tables 3.1 and 3.2. From the result it is assumed that the less proficient the group is, the more difficulty it had using ANCOs effectively, which also leads to an affirmative impression of the RQ2 and RQ3. The two observations seem to sug- gest that Nakano (1996) and Chen (1990) could prove correct.

6.References

Bongaerts, T., and Poulisse, N. (1989). Communication strategies in L1 and L2: Same or different?

Applied Linguistics, 10(3), 253-268.

Chen, S.Q. (1990). A study of communication strate- gies in interlanguage production by Chinese EFL learners. Language Learning, 40(2), 155- 187.

Heaton, J. (1975). Beginning Composition through Pictures. Harlow:Longman.

Iwai, C. (1995). Second language proficiency and communication strategies in L1 and L2. NIDA- BA, No.24: 11-20.

Iwai, C. (2000). 『第二言語使用におけるコミュニケー ション方略』(Communication Strategies in L2 use) Keisuisha.

Kellerman, E., Ammerlaan, T., Bongaerts, T., and Poulisse, N. (1990). System and hierarchy in L2 compensatory strategies. In R.C. Scarcella, E.S.

Andersen, and S.D. Krashen (Eds.), Developing communicative competence in a second lan- guage. (pp.163-178). Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle Publishers.

Matsumoto, K. (1999). On L2 Communication Strategies. Bulletin of Center for Educational Research and Development, Aichi University of Education, N0.2: 129-134.

Matsuno, S., Humphrey, F., and Humphrey, G. (1999).

『 TOEIC Test模 擬 試 験 パ ー フ ェ ク ト 攻 略 』 (Practical Test of TOEIC ) Kiriharashoten.

Nakano, S. (1996). 「英語苦手学習者のCommunication Strategy の使用―回顧的なデータ分析を通して」

(Communication Strategies Used by Slow Learners of English-A Retrospective Data Analysis) The Chugoku Academic Society of English Language Education, No 25: 111-118.

Poulisse, N. (in collaboration with T. Bongaerts and WATANABE Kazuo and GAPPA Akira

E. Kellerman) (1990). The use of compensatory strategies by Dutch learners of English.

Dordrecht: Foris publications Holland.

Tarone, E. (1983). Some thoughts on the notion of communication strategies. In C. Faerch and G.

Kasper (Eds.), Strategies in interlanguage com- munication. (pp. 61-74). London, UK: Longman.

Tsuchimochi, K. (2001). A Study of Communication Strategies Use by Japanese EFL Learners.

Bulletin of Kagoshima Prefectural College, No.52: 21-36.

Appendix A Questionnaire about the Learner s English Background

1 お名前

2 どのくらい英会話を学習されていますか。

3 今まで受けた英語の試験について 英検

TOEIC TOEFL

4 今までに旅行や留学などで海外に行ったことがあ りますか。

1 はい 2 いいえ

5 4ではいと答えた方にお聞きします。どちらの国 にどの位行かれていましたか。

1 Name

2 How long have you been learning English con- versation?

3 What types of English tests have you taken before?

Step Test TOEIC TOEFL

4 Have you ever been abroad for travel or for study?

1 Yes 2 No

5 If yes, which country did you go to and how long did you stay there?