■

Research Notes■

Child

Loss Experience

and its Effect

on Fertility:

A Case

Study

of Two Ethnic

Communities

of Nepal

●

Nabin Aryal

1. Introduction

1.1 General backgrounds

Health policy makers of Nepal have always stressed that the high growth rate of population could have a hugely negative impact on different aspects of human life and potentially hinder the process of national development. Thus, the reduction of population growth rate has always been a top priority in Nepal's developmental policy. Since 1956, Nepal has embarked on a strategy of planned development, with periodic development plans as the main instruments of developmental policies and programs. Within these plans and policies, population has always been an important component. The ninth five-year plan was designed as part of a 20-year long-term plan. The government has also adopted various policies to achieve the goal of reduc-ing the total fertility rate to the replacement level within 20 years [Ministry of Popu-lation and Environment (MOPE hereafter) 2001]. Similarly, the recently unveiled tenth five-year plan stresses the reduction of both infant mortality and total fertility rate as the major development agenda [Nepal Planning Commission 2005].

According to preliminary findings from the country's 2001 National Census and its National Demographic Health Survey, Nepal's fertility and mortality rates dem-onstrate a downward trend [Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS hereafter) 2002]. As with most South-Asian countries, a decline in infant mortality in Nepal has been fol-Nabin Aryal, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Postdoctoral Fellow,

Insti-tute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University.

Area of Research: Demography, Social Development of Nepal.

Articles: Aryal N. (2004), "Ethnicity and Fertility: Micro Level Household Survey of Two Ethnic Communities of Nepal", PhD thesis, Hitotsubashi University.

Aryal, N. (2005), "Fertility and Its Determinants in Nepal: A Micro Approach, Results from Household Survey of Two Ethnic Communities", Nepal Population Journal (Forthcoming).

lowed by a reduction in fertility [Collumbien et al. 2001]. Thus, it is extremely im-portant to recognise the mortality trend in order to better understand the fertility tran-sition. According to Cleland, decline in infant and childhood mortality is a precondition for fertility decline [Cleland 1998]. The relationship between childhood mortality and outcome of fertility has been investigated and discussed extensively by both the academic community and governmental policy-makers. However, the focus of research so far has been at the macro-level, thus, there is only limited study in the field of mortality and fertility in Nepal at the local community level. Although the government has long adopted different population policies according to ecological regions of the nation, adequate micro-level surveys, leading to an effective policy implementation, arc yet to be conducted. Furthermore, comparative demographic studies of ethnic groups in the nation are extremely rare.

The present study analyses the relationship between mortality and fertility behaviour of two ethnic communities of Nepal: the Bahun/Chettri, the major ethnic group of Nepal with an Indo-Aryan ethnic background, and the Tamang, a minority of Tibeto-Burman descent. According to the latest census data, the Chettri are the largest ethnic group of Nepal and, along with the Bahun, constitute 30 percent of the total population. On the other hand, our other study group, the Tamang, are the fifth largest ethnic group and only form 5.64 percent of the national population.1)

In the context of Nepal, a micro-demographic study focusing on a particular eth-nic community has been initiated by Alan Macfarlane. Macfarlane has studied the demographic behaviour of Gurungs, a minority ethnic group of Nepal, where he fo-cused on the land resources and population problems faced by this subgroup in the Thak region of Nepal [Macfarlane 1976]. Other significant contributors to the micro-demographic researches include: William Axinn, Dilli Ram Dahal and Thomas Fricke. All of these scholars have dedicated their researches on the social changes and fertility outcome of the Tamang subgroup of Nepal. While Fricke conducted his field study in a remote Timling region of the country, Axinn focused his research on a relatively urban setting. Fricke demonstrated how the Tamang of the Himalayan re-gion underwent a cultural, demographic and familial change [Fricke 1994]. Dahal and Fricke conducted a number of researches on the Tamang in various parts of the coun-try, and tried to compare the social transformation and fertility transition of this sub-group [Dahal and Fricke 1998]. While Macfarlane, Dahal and Fricke used anthropological approaches for their demographic research, Axinn utilised compo-nents of sample survey techniques along with anthropological method. Axinn utilised the survey data to demonstrate how exposure to the monetary economy and non-fa-milial experience of the Tamang affected their fertility decisions [Axinn 1992]. What limited research work that exists on micro-demography of Nepal has focused exclu-sively on the minority of Tibeto-Burman descendents, with an emphasis on fertility. Furthermore, the researches so far have failed to do any comparative studies between

different subgroups and have failed to include major ethnic groups like the Bahun/ Chettri. At the same time, key issues, such as childhood mortality and healthcare sta-tus of children and their effect on fertility, have also not been properly investigated.

The chief objectives of this paper are first to understand the status of the childhood mortality rate, and then to investigate the relationship between childhood mortality and fertility in these two ethnic communities. Additionally, we will compare the childhood mortality between two generations of mothers in the study area. We be-lieve that the present study will complement the researches on the micro-study of de-mographic transitions of the Tamang sub-group of Nepal, initiated by Axinn, Fricke and Dahal. At the same time, as there are no other micro-studies on the demographic behaviour of the largest ethnic group, Bahun/Chettri, the present study will be valu-able to those who are involved in the demographic study of various ethnic groups of Nepal.

1.2 Data and methodology

The primary data used for the current research have been obtained by the present author in the outskirts of the Kathmandu valley during September-November 2002. The study area, approximately 25 kilometres from Kathmandu, could be reached by a two-hour bus trip. The fieldwork was carried out in two villages under one Village Development Committee (VDC), the lowest administrative body of the kingdom.2) The definition of village in this case is a natural settlement of an ethnic group (natu-ral village or hamlet) where people usually live with their relatives in a cluster of houses.

Segregation based on ethnicity is the norm among the various groups of people in Nepal, who tend to dwell together in one village. This type of segregated settlement pattern based on ethnicity is found in most rural areas of Nepal [Dahal et al. 1996; Fricke 1994]. The survey site was chosen not only because colonies of the different ethnic groups were located in the area, but also because of the present author's famil-iarity with the cultural and socio-economic conditions of the region. This made it pos-sible for the author to perform a more in-depth qualitative study. In addition, the settlement pattern of the present study area is considered to be typical in the context of rural Nepal. Data for the research were collected via the questionnaire and inter-view methods.

The questionnaire primarily dealt with two important issues: community and de-mography. The community study included: family composition, household and so-cial activities, land holding, income, cropping pattern, village infrastructures, household ownership, principal decision-makers in various household activities and the status of women. Information on age and sex group, marriage, fertility, maternity, family planning, children's health and mortality were collected for the demographic study. In order to conduct an in-depth study, several qualitative interviews with some

informants and meetings with knowledgeable villagers were also carried out. All the households of the Bahun/Chettri and the Tamang in their villages were sur-veyed in the present study. In total, 188 ever-married women aged 15 and above liv-ing within these communities are included in the analyses.

Since our study has a relatively small number of observations, calculating infant and childhood mortality rate bears little significance. In fact, there were only two in-cidences of infant and childhood deaths reported in the Tamang community and none for the Bahun/Chettri community during the year of our survey.3) In addition, since the study of childhood mortality has never been carried out in this region, it is ex-tremely difficult to ascertain the status of mortality. For this research, we have se-lected the child loss experience by mothers of the new and old generations to understand childhood mortality. Since our respondents hesitated to provide the exact number of childhood deaths, we employed the questionnaire method to obtain whether the mother had experienced child/infant loss in the past. A mother with child/ infant (under the age of five) loss in the past has been coded as '1' and those without such experience as '0'. It should be stressed that the dichotomous child loss experi-ence variable does not reflect the actual childhood mortality rate, which ultimately affects fertility. However, child loss experience is a crucial variable in understanding the fertility behaviour of mothers in Nepal [Adhikari 1996], and in the absence of childhood mortality data for the area, we have opted to use child loss experience as a substitute for childhood mortality in this research. Children ever born (CEB) is the proxy for fertility in the current study and is defined as all live births given by moth-ers aged 15 years and above.4) In order to compare the child loss experience between two generations, mothers who have not yet completed the reproductive span, ages between 15 and 45, are classified as "new" or "young" generation while ages 46 and over are classified as "old" generation.5) Chi-Square tests were employed to detect the equality of the probability of experiencing child loss between the old and young generations of mothers in the study area. Similarly, these tests were utilised for the independence of children ever born (CEB) and the mother's experience of child loss. These statistical tests were performed using a software package, Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 11.

1.3 Socio-economic and demographic characteristics of the two communities The Bahun/Chettri of the present study area were believed to be migrants from the remote hill districts of Gorkha, and have been residing in the village for the past 250 years. The Tamang of the study area were migrants from Makawanpur, an adjacent district of the capital city of Kathmandu. Both the Bahun/Chettri and Tamang vil-lages were in the Dakshinkali VDC. The Bahun/Chettri of the study area were settled in a relatively higher altitude. The Tamang, traditionally known to settle in higher mountains, were settled near the Bagmati River.

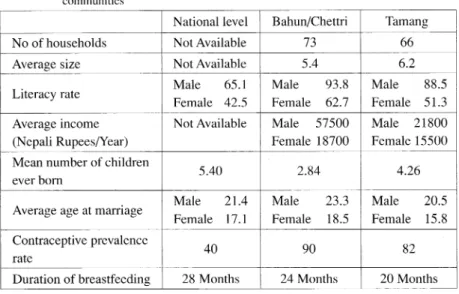

Selected socio-economic and demographic indicators of the two communities have been summarised in the following table.

The present survey revealed that the average household sizes of Bahun/Chettri and Tamang communities were: 5.4 and 6.2 respectively. Indispensable infrastructures, such as schools and healthcare facilities, were readily available to the Bahun/Chettri, whereas the Tamang villagers were deprived of easy access to these resources. While a government-run primary school was the sole educational facility in the Tamang community, two primary schools, a high school and a junior college were available in the Bahun/Chettri community. The literacy rate was also vastly different between the two communities. The literacy rate has been calculated by proportions of popula-tion over the ages of 10 and above that can read and write Nepali. Even though the literacy rate compared to the national level was relatively high in both communities, the Bahun/Chettri fared better in this category as well. Although the gender gap in the literacy rate was persistent in both communities, the disparity was less significant in the Bahun/Chettri community.

Agriculture was the primary source of economic activity in the study area with a majority of the women in these communities engaging solely in agriculture and ani-mal husbandry. The Bahun/Chettri women did not engage in agricultural labour for wage, whereas it was the principal means of earning for women of the Tamang

com-Table 1 Selected socio-economic and demographic data of national level and two ethnic communities

Source: Based on a survey by the present author in October 2002. Ministry of Population and Environment of Nepal 2001.

munity. While a few of the Bahun/Chettri women were also employed in the govern-mental and private non-labour sector, participation by the Tamang women in these

fields was insignificant. The Bahun/Chettri males were less engaged in agricultural labour for wage as they were more likely to hold governmental and teaching posi-tions. On the other hand, the Tamang tended to own small businesses, such as small shops, more often than the Bahun/Chettri did. Our survey revealed that on average the Bahun/Chettri generated twice as much income as the Tamang did. Furthermore, the gender disparity in income was more prominent in the former community.°) A vast disparity between the two communities was observed when we examined the owner-ship of durable goods. Durable goods, such as television and other electronic prod-ucts, and in some cases automobiles, were far more prevalent in the Bahun/Chettri community. While most of the households were electrified in the study area, water supply and telephone services were inadequate in the Tamang community.

As Table 1 demonstrates, the Bahun/Chettri had more number of children ever born (CEB) than the Tamang. The Tamang had a slightly fewer number of children ever born (CEB) compared to the national level. Compared to the national level, the Bahun/Chettri had higher age at marriage for both male and female. However, the age at marriage for male and female in the Tamang community was slightly lower than that of national average. Contraceptive prevalence rate is defined here as the pro-portion of couples who have used at least one modern means of contraceptives. Our study revealed that the rate of prevalence of modern contraceptive methods is quite high in both of the study area, though this rate is still low at the national level. A universal and prolonged breastfeeding practice was observed in both the national level

and our study area. After revealing basic socio-economic and demographic

indica-tors of the study area, we will tackle the issue of child loss experience and fertility in the two communities.

2. Child loss experience and fertility in the study area

2.1 Status of child loss experience by mother in the study area

In Nepal, a large proportion of the mothers who experienced child loss, lost chil-dren under the age of five [Ministry of Health (MOH hereafter) 2001]. In general, there are endogenous and exogenous factors that affect child loss. Among the endog-enous factors, which are more of a biological nature, are the age of the mother and the spacing time between births. The exogenous factors are related to postnatal and neonatal deaths or social, cultural, economic and environmental factors [Gill 1985]. In the context of our study area, the most important factors for child loss are food shortages, contaminated water, crowded and sub-standard housing, unchecked infec-tious diseases, absence of day-care facilities for the children of working mothers and the lack of minimally adequate free medical care. The lack of general knowledge

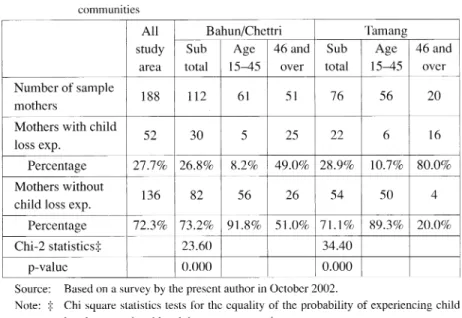

about health is yet another contributing factor. Medical facilities were found to be distributed very unevenly in our study area. For example, qualified medical services are available only in the local growth centre and are largely confined to a relatively favoured social stratum. These factors contribute to differentials in the child loss ex-perience. In order to evaluate the status of child loss experience by mothers, we have opted to compare the statistics of child loss experience by older (age 46 and above) and newer (age 15 to 45) generations of mothers within the two ethnic communities. The table 2 represents the descriptive statistics of child loss experience in the two ethnic communities.

The information in the table above suggests that a higher incidence of child loss was experienced by mothers aged 46 and over in both communities. Although the observations are relatively small, 80 percent of the older generation Tamang mothers had experienced at least one child loss in their lifetime, whereas 49 percent of the older generation Bahun/Chettri mothers experienced child loss. A significant decrease in child loss experience can be seen in both communities among the age 15 to 45

cohorts. In fact, the child loss experiences in the Bahun/Chettri community and

Tamang community have dropped to approximately 8 percent and 10 percent respec-tively. However, due to the fact that the new generation mothers have not yet com-pleted the reproductive span, a few might experience child/infant death in the future.

Table 2 Child loss experience by mothers of new and old generations in two ethnic communities

Thus, the child loss experience is only an approximate measure of childhood mortal-ity. Hence, analysing the mortality rate solely on child loss experience by mothers results in a composition bias problem.7 The composition bias problem can be ad-justed by including the dependency of probability of child loss experience on

chil-dren ever born (CEB).8) These results have been summarised in Table 3.

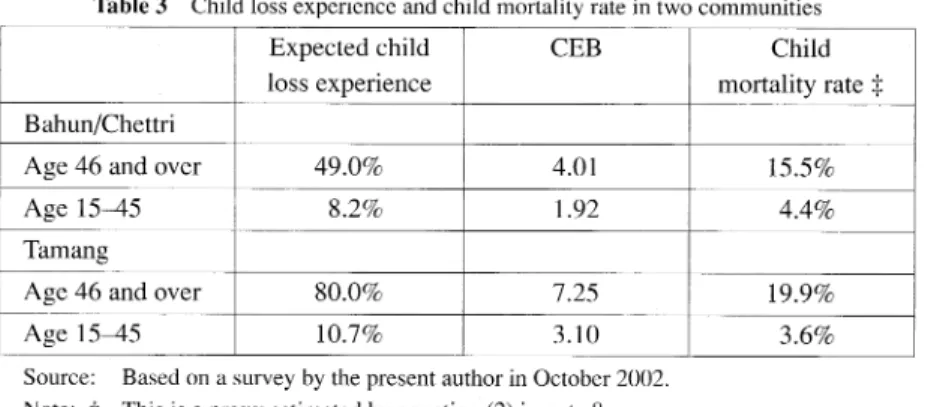

The results in Table 3 demonstrate that along with the child loss experience by mothers, the childhood mortality rate has also seen a sharp decline among the new generation of mothers in the study area. In fact, the childhood mortality rate has de-clined from 15.5 percent to 4.4 and from 19.9 percent to 3.6 percent among the new generation mothers in the Bahun/Chettri and the Tamang communities respectively.

It is evident from the results in Table 2 and Table 3 that the child loss experience and the childhood mortality rate have been reduced in recent years. In the following section, we will examine a number of factors that may have contributed to these re-sults. Chief among these factors seems to be the vast improvement in the healthcare status of both the mother and child.

2.2 Child healthcare status in the two communities

Coupled with better maternal care, improved pre and postnatal care of the new-borns can be linked to the decline in child loss experience among new generation mothers in the study area. Although there has been improvement at the national level in the infant mortality rate, a significant decline in the neonatal mortality rate has not been observed.9) Although we do not have any data on the trends of infant mortality rates or the causes of infant/child mortality in the region, we have obtained some qualitative data on reproductive healthcare, namely, the place of delivery, regular check-ups of newborns and immunisation in these two ethnic communities. Thus, in this section, we will focus mainly on the postnatal care of newborns in the region.

Table 3 Child loss experience and child mortality rate in two communities

Furthermore, we will also compare the statuses between younger and older genera-tions of mothers in the study area.

Traditionally, newborns were delivered at home without the assistance of any trained healthcare professionals. This has resulted in not only a higher infant mortal-ity rate but also a higher maternal mortalmortal-ity rate."

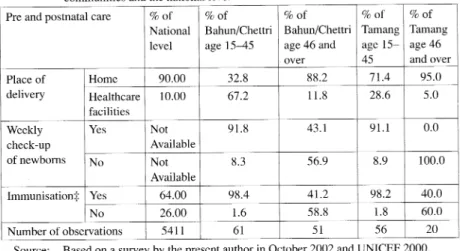

Table 4 demonstrates that most of the births took place at home for the older age cohorts of both communities. Merely 8 percent of the Bahun/Chettri and only one Tamang respondent cited that they had their newborn delivered at a healthcare facil-ity. While a majority of the Bahun/Chettri mothers now rely on healthcare facilities to deliver their babies, accounting for 67 percent of all deliveries, only 30 percent of Tamang mothers rely on similar facilities. Since the Tamang village has neither healthcare facilities nor a reliable source of transportation, most babies are still de-livered at home without the presence of reproductive healthcare professionals or trained midwives. Furthermore, if we see the delivery practice at the national level, merely 10 percent of the mothers deliver their babies at healthcare facilities. These factors are responsible for the still high maternal and infant mortality rates in the country.

The present study questioned mothers on whether their newborns were taken to healthcare facilities for regular check-ups. The study revealed that only 42 percent of the Bahun/Chettri mothers, and none of the Tamang community of the older cohort,

Table 4 Postnatal care status between mothers of new and old generations in two ethnic communities and the national level

Source: Based on a survey by the present author in October 2002 and UNICEF 2000.

Note:•ö Includes only BCG for national level and Tamang age 46 and over. All others in-clude BCG, DPT, polio and measles.

reported taking their babies to healthcare facilities for regular check-ups . However, the healthcare status of newborns has been significantly improved in recent years in both communities. Approximately 90 percent of all respondents stated that they took their newborns to the nearest healthcare facilities for a weekly check-up . These figures were not available at the national level .

Immunisation of newborns might be one of the major factors behind the decline in

infant/child mortality in the region. According to the World Bank , childhood

immunisation is the most effective form of medical intervention to prevent death and disease in Nepal [World Bank 1990].") The majority of mothers aged 46 and above from both communities in our present study cited that they did not immunise their children. Since the introduction of the "door to door service"12) by the government of Nepal, the use of immunisation has been rapid and almost universal . Almost all moth-ers of the younger cohort had their children immunised against Bacille Diptheria/Per-tussis/Tetanus, (DPT), polio and measles in both of our study villages . There was one incidence from each village of not immunising their children against these infectious diseases; the reason, however, was not stated .

It is clear from our study that the healthcare status of newborns has been

significantly enhanced in both ethnic communities . Compared to the older genera-tion, the new generation mothers frequently visit healthcare facilities for a check-up of their newborns. As stated earlier, it is quite clear that the number of mothers with child loss experience has declined among the newer generation of mothers in both of

the ethnic communities of the study area. However , the older generation Bahun/

Chettri mothers had fewer child loss experiences and a lower childhood mortality rate compared to their Tamang counterparts. This difference in the older generation

moth-ers of these two communities might be explained by the disparity in access to

healthcare facilities in the study area. For example, we observed that the Bahun/ Chettri mothers of older generation had a higher incidence of newborns delivered at a healthcare facility, as well as better postnatal care compared to the older generation Tamang mothers. Even in the absence of the local health post , which was established in 1985, the Bahun/Chettri had easy access to healthcare facilities in Kathmandu due to the availability of an all-weather road and transportation .13) On the other hand, the Tamang community did not have an all-weather road or public transportation , which restricted access to better neonatal and medical care. The Bahun/Chettri of older gen-eration had also immunised their children against infectious diseases , such as DPT and measles, which were not covered by the "door to door service" offered by the government.") In our study, we observed that another crucial element in the disparity between child loss experience by the older generation of Tamang and Bahun/Chettri was the difference in their treatment of their children against diarrhoeal diseases . The

treatment of diarrhoeal diseases-one of the leading causes of death among

ac-cess to treatment resulted in higher child mortality in the Tamang community.15) How-ever, with the establishment of the local health post in the locality and a wider cover-age of the "door to door service", the healthcare status of newborns has been enhanced in both of these communities. The government has enhanced the "door to door service" by including the immunisation of DPT, BCG, polio and measles. Addi-tionally, all households have benefited from the availability of a free diarrhoeal treat-ment and vitamin A campaign.16) This factor might have contributed to fewer child loss experience and lower childhood mortality rate among the new generation of mothers in both of these communities. After assessing the child loss experience and the neonatal health status, the relationship between child loss experience and the out-come of fertility is discussed in the following section.

3. The relationship between child loss experience and fertility in the

study area

The positive correlation between child loss experience and fertility has been well documented [Cleland 1994]. In other words, it has been found that higher rates of child loss usually result in higher fertility rates. The reason for such phenomena is often explained by the "child-survival hypothesis", which asserts that parents must first have confidence in their children's prospects for survival before they will be re-ceptive to modem family planning and lower their norm of desired family size.

The high rate of child loss leads to gross reproductive waste, which in turn drains the physical, economic and psychological resources of women in Nepal. Therefore, child loss experience has a substantial positive impact on fertility and is strongly influenced by many biological and socioeconomic factors [Cleland 1998].17)

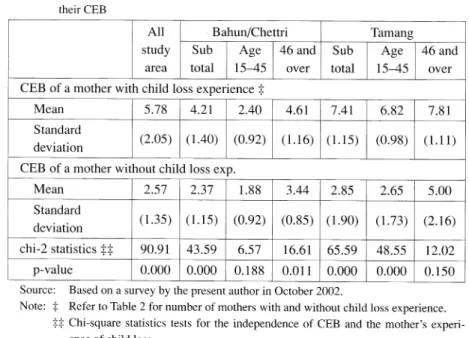

It seems that a higher incidence of child loss experience tends to result in an in-crease of the fertility rate. By utilising the data obtained from our study area, we have examined whether mothers with child loss experience have a higher mean number of children ever born (CEB). The results are summarised in the following table.

The table demonstrates that mothers without child loss experience tend to have a fewer number of children compared to those with such experience within both com-munities. In the Bahun/Chettri community, the mothers without child loss experience had on average of 5.78 mean number of children ever born (CEB), as opposed to 2.57 number of children ever born (CEB) for mothers without such experience. Similarly, mothers with and without child loss experience had on average 7.41 and 2.65 chil-dren ever born (CEB) respectively in the Tamang community. Even when divided into two generations, a lower number of children ever born (CEB) was observed for moth-ers without child loss experience in both of these communities. However, this is more evident in the younger generation of the Tamang community. In fact, almost four fewer children ever born (CEB) were recorded for the 15-45 age group of the Tamang

community.18) The observation of a higher number of children ever born (CEB) for mothers with child loss experience in this study area supports the "child-survival hy-pothesis". Furthermore, high correlation between a mother's child loss experience and higher fertility in the current study agrees with results from studies that have been carried out in Nepal and other developing nations [Cleland 2001]. In the context of Nepal, scholars have observed that in each and every case, women who have lost at least one child go on to have a larger number of children ever born (CEB) compared to those mothers who have not lost a child [Adhikari 1996; Aryal 1997] .

From our interviews with the mothers in these communities , it was evident that they were quite aware of the reduction in the death of infants/children compared to the past. These mothers were also conscious that the greater availability of healthcare facilities, doctors and modem medicine has attributed to a higher survival rate of in-fants and younger children. The younger generation mothers often replied that the issue of infant/child deaths was only a slight concern; consequently, they bore fewer children. On the other hand, the older generation mothers often stated that in the past it was necessary to have more children in order to insure against the risk of losing children.

Table 5 Cross tabulation of proportion of mothers with and without child loss experience and their CEB

4. Summary and Conclusions

Utilising micro-data, obtained through fieldwork by the present author, the paper tackled the issues of child loss experience and the outcome of fertility within two ethnic communities of rural Nepal. The two ethnic groups studied were the Bahun/ Chettri, the majority of the Nepalese population, and the Tamang, an ethnic minority. With regard to socio-economic and demographic indicators, these two ethnic com-munities displayed sharp contrasts. The main objective of this paper was to unveil the status of child loss experience by mothers in the study area and then to detect the relationship between such experience and fertility. A major finding of the study is that fewer new generation mothers had experienced child loss compared to their older counterparts. Furthermore, the childhood mortality has also dropped sharply in these two communities. The decline in child loss experience and childhood mortality is mainly due to an improvement in reproductive healthcare and postnatal care. The in-creased incidence of delivery in healthcare facilities, regular check-ups and immunisation of newborns were observed in both ethnic communities. It was also observed that a higher number of children ever born (CEB) was experienced by those with child loss experience in both communities.

Within our study, we observed that the state of child loss experience and fertility has improved among the new generation mothers, regardless of their ethnicity. How-ever, the older generation Bahun/Chettri had fewer child loss experiences and a lower childhood mortality rate compared to their Tamang counterparts. The fewer child loss experience in the older Bahun/Chettri community can be attributed to better access to healthcare services in Kathmandu even in the absence of a local health post and a comprehensive "door to door service" by the government. However, with the estab-lishment of a local health post and the enhancement of the "door to door" service, both the Bahun/Chettri and the Tamang experienced success in lowering child loss experience and childhood mortality rate among the new generation mothers from both communities in the study area. Thus far, we have only analysed the state of child loss experience and fertility in the study area. We observed that child loss experience has declined in the study area, and that mothers with child loss experience tend to have a higher number of children ever born (CEB). However, due to the data constraint of not having an accurate mortality rate, obtaining direct correlation of mortality on fer-tility was not feasible in the present study. In order to understand the impact of mor-tality on fertility in the study area, multivariate analyses become essential. Thus, gathering accurate infant/childhood mortality data and analysing the trajectory of ef-fect of mortality on the outcome of fertility within these two ethnic communities are issues left for future research. Finally, a study of a secluded settlement pattern is not sufficient in assessing the effect of settlement pattern on the child loss experience and fertility of the Bahun/Chettri and Tamang ethnic groups. A micro-study of an

ethni-cally mixed settlement pattern becomes crucial for such an assessment . Despite a secluded settlement pattern being the norm in most areas of Nepal , a fieldwork of an ethnically mixed settlement pattern is feasible within a semi-urban setting . This type

of study has been left as a future research agenda.

Notes

1) Along with eleven major ethnic groups, there are seven more ethnic groups each of which forms less than two percent of the population. Additionally, there are eighty-three other identified ethnic groups that have a population of one percent or less [CBS 2001]. It should be stressed that the classification of "ethnicity" by the Central Bureau of Statistics of Nepal has always been highly controversial, because it puts together caste, ethnic group, reli-gious background and tribal groups in the same category. Official statistics on the ethnic population in Nepal are highly problematic partly because the records are based on re-ported "mother tongue" in the case of the national census, and on other criteria which are often ill-defined in other surveys [Dahal and Fricke 1998] . A major flaw in the classification of ethnicity by mother tongue is that the indigenous languages of Tamang, Gurung and Tharu tend to fade out with newer generations accepting the "official lan-guage", Nepali.

2) The fieldwork was carried out in Dakshinkali Village Development Committee. However, the locality is known as Pharping region.

3) While infant mortality rate calculates the death rate of infants under the age of one; child-hood morality rate is the death rate of children under the age of five.

4) CEB calculates only live births. It does not count the miscarriages and stillbirths. 5) Demographers consider the age of 15 to 45 of women as conceiving period [Petersen and

Petersen 1986].

6) The term income here refers to "reported income". This is meant to emphasise the well-being and bargaining power of a wife versus her husband. Thus, the income as reported by the respondents does not include income due to households' joint activities or imputed value of home produced food/commodities. Since the information was based on reports by a husband and a wife, this variable may have substantial measurement errors. 7) Since the number of children ever born is higher in older generation than in younger

gen-eration, it is possible to get higher child loss experience in older generation than in younger generation even if the mortality rate is the same. Thus, the inference drawn without con-sidering this fact is said to be subjected to "composition bias".

8) Composition bias can be adjusted using the fact that probability of child loss experience is dependent on the number of children ever born. Let :r be the probability of a child of the sampled mothers to die under the age of five and n be the expected number of children ever born. So the probability of having child loss experience is given by

(1)

By inverting this equation, we can estimate ƒÎ as

(2)

We can use this estimate as a proxy for the childhood mortality rate.

9) In fact, out of every 1000 births, 39 die within the first month of their life. Among new-borns, a low birth weight alone accounts for 64-84 percent of deaths, followed by other

complications such as birth asphyxia, birth injury, infections, neonatal tetanus, hypother-mia and congenital malformations [MOPE 2000].

10) According to the latest figures, 12 women die per day in Nepal as a result of complica-tions related to pregnancy [MOH 2001]. Most of these deaths occur due to the lack of access to basic healthcare during pregnancy, childbirth and postnatal care. A study by the Ministry of Health has concluded that maternal morbidity and mortality are closely re-lated to services for prenatal care, safe delivery and postnatal care. However, despite sig-nificant improvements in the health infrastructure of the nation, deliveries attended by healthcare providers remain dismally low in Nepal [MOH 2001].

11) According to official government reports, Nepal has had tremendous success since the in-ception of its immunisation program in 1977. The national immunisation coverage in 1989 was as high as 95 percent for tuberculosis (Bacille Calmette-Guerin, or BCG), 80 percent for polio and Diptheria/Pertussis/Tetanus (DPT) and 69 percent for measles. However, a UNICEF sample study showed that only about 64 percent of the newborns were immunised in Nepal [UNICEF 2000].

12) With the establishment of the local health post, local healthcare service volunteers together with health professionals from the Ministry of Health (MOH) visit all households in the study locality to provide various child healthcare services.

13) In an interview with the present author, the Village Development Committee chairman stated that the Bahun/Chettri took their children to Kanti Hospital in Kathmandu for vari-ous child health services in the absence of a local health post. Furthermore, knowledge-able Tamang villagers stated that they did not take their children to any healthcare facilities in the past due to lack of transportation.

14) According to local health post record, "door to door service" of health services started from 1986. In the first phase, universal coverage of BCG and polio immunisation was implemented in the Pharping region. DPT and measles immunisation was not available

(health post records).

15) Local health post record shows that majority of child death in the region in the past oc-curred from diarrhoeal diseases, often by contaminated water. The cure for such diseases was not available in the Tamang region. From 1990, the health post started distributing Jeevan Jal, Oral Rehydration medicine free of charge in the all households in the region

(health post records).

16) According to local health post records, universal coverage of immunisation for all infec-tious diseases and vitamin A program started in 1998 in the region.

17) Cleland further observes that the dominant research issue in the mortality-fertility rela-tionship has been the "replacement theory", the psychological and behavioural response by mothers seeking to replace a lost child. As evidence regarding the effect of lactation on ovulation accumulated, it was realised that one pathway to influence fertility was strictly physiological. An early child death terminates breastfeeding and thus permits an early re-turn to ovulation, which in re-turn, shortens the interval to the next birth [Cleland 2001]. However, the biological effect of child death may differ based on the age of death. The effect of breastfeeding and ovulation on fertility is stronger for those mothers who lose their infant soon after birth. Since we do not have the exact age when mothers have expe-rienced child loss, it is difficult to understand to what extent the biological effect of child loss contributed to the fertility in the study area.

18) The relationship between child loss experience and the mean number of children ever born (CEB) was not statistically significant for the new generation mothers in the Bahun/Chettri community. This is primarily due to the very low proportion of mothers in this category that experienced child loss. On the other hand, a larger proportion of the older generation mothers of the Tamang community had experienced child loss. Since there is no variation in the child loss experience variable, no significance was obtained, thus, the apparent rela-tionship between child loss and mean number of children ever born (CEB) was not ob-tained for this category.

REFERENCES

Adhikari, K.P., 1996, "Effect of Infant and Child Mortality on Fertility: Biological and Voli-tional Responses", Nepal Population Journal 5, pp. 44-55.

Aryal, N., 2004, Ethnicity and Fertility: Micro Level Household Survey of Two Ethnic Commu-nities of Nepal. Ph.D. thesis. Hitotsubashi University.

Aryal, R. H., 1997, "Theoretical Experience of Fertility Change", Nepal Population Journal 6, pp. 1-10.

Axinn, W., 1992, "Family Organization and Fertility Limitation in Nepal", Demography 29,4, pp. 503-21.

Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), 2001, Population Census of Nepal, Kathmandu: Govern-ment of Nepal Publications.

Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), 2002, Population Monograph of Nepal, Kathmandu: Gov-ernment of Nepal Publications.

Cleland, J., 1994, The Determinants of Reproductive Change in Bangladesh: Success in Chal-lenging Environment, Washington, D.C.: World Bank Publications.

Cleland, J., 1998, "Understanding Fertility Transition: Back to Basics", in S. Thapa, A.G. Niedell and D.R. Dahal (eds.), Fertility Transition in Nepal, Kathmandu: Mass Printing Press, pp. 199-213.

Cleland, J., 2001, "The Effects of Improved Survival on Fertility: A Reassessment", Population and Development Review 27, pp. 60-92.

Collumbien, M., Timaeus, I.M., and Acharya L., 2001, "Fertility Decline in Nepal", in Z.A. Sathar and J.F. Phillips (eds.), Fertility Transition in South Asia, Kathmandu: Mass Printing Press, pp. 99-120.

Dahal, D.R. and Fricke, T.E., 1998, "Tamang Transition: Transformations in the Culture of Childbearing and Fertility among Nepal's Tamang", in S. Thapa, A.G. Niedell and D.R. Dahal (eds.), Fertility Transition in Nepal, Kathmandu: Mass Printing Press, pp. 59-77.

Dahal, D.R., Fricke, T.E., and Lama R.K., 1996, "Family Transitions and the Practice of Brideservice in the Upper Ankhu Khola: A Tamang Case", Contributions to Nepalese Studies 23, pp. 377-401.

Fricke,T.,1994, Himalayan Households: Tamang Demography and Domestic Process, New York: Columbia University Press.

Gill, S. S., 1985, "Politics of Birth Control Program in India", Socialist Health Review 4, pp. 20-27.

Macfarlane, A., 1976, Resource and Population: A Study of the Gurungs of Nepal, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ministry of Health (MOH), 1996, MOH Report 1995, Kathmandu: Government of Nepal Publi-cations.

Ministry of Health (MOH), 2001, MOH Report 2000, Kathmandu: Government of Nepal Publi-cations.

Ministry of Population and Environment (MOPE), 2000, MOPE Report 1999, Kathmandu: Gov-ernment of Nepal Publications.

Ministry of Population and Environment (MOPE), 2001, MOPE Report 2000, Kathmandu: Gov-ernment of Nepal Publications.

Nepal Planning Commission, 2005, Tenth Plan, Electronic version, www.npc.gov.np/tenthplan/ the_tenth_plan.htm

Petersen, W. and Petersen, R., 1986, Dictionary of Demography: Terms, Concepts, and Institu-tions, New York: Greenwood Press.

UNICEF, 2000, The State of the World's Children 2000, New York: Oxford University Press. World Bank, 1990, World Development Report, 1990, New York: Oxford University Press. Village records:

Dakhsinkali Village Development Committee, Gau Bikas Pustika (Village Development Com-mittee Record Book), Kathmandu.

Shesh Narayan Swastha Kendra, Swastha Sewa Pustika (Health Post Record of Healthcare Serv-ices), Kathmandu.