25

Theory and Practice of Japanese ODA

Eiichi IMAGAWA

(Soka University)

I : Japan As A Top Donor of ODA

In an annual 1995 report on Japan's Official Development Assistance(ODA), the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan proudly proclaimed that the dollar value of the ODA disbursement by Japan in 1994 amounted to $13.24 billion, the largest in the world for four consecutive years.

According to the same report, the Japanese ODA accounts for 22 .9% of the total amount of aid given by developed countries who belong to the OECD's Development Assistance Committee(DAC).

A total of 158 countries and regions were receiving Japan's ODA in 1994. Among those recipient countries, Japan was the largest donor of ODA in 34 countries in 1993 and the second largest in 29 countries at the same year.

In its report, the Foreign Ministry also emphasizes that Japan's ODA is playing a significant role in the economic and social development of most of the developing countries and has been an important instrument for building friendly relations between Japan and those recipient countries.

Thus, as shown in the official report, now the Japanese ODA is quite an important element of the economy of the developing countries. So it also becomes very important task to analyze the theory and practice of the Japanese ODA when we try to find further effective ways to use the Japanese ODA for the benefit of the developing countries. Then, in this paper, I would like to analyze the theory and practice of the Japanese ODA.

II: A Key Element Of Japanese ODA Theory

Behind the Japanese ODA policy and practice, there is an important theory on economic develop- ment. And also the most important thing is that the majority of Japanese economic community in- cluding businessmen, government officials and economists has firmly believed in this theory of economic development.

This was a theory that economic development could be attained by industrialization which was led by capitalist groups who were assisted by clever government officials. The Japanese economic community also believed in a theory that industrialization should start with building of economic

( oDTAZI1996$ 7 4)`Z L. )

26 T-'RJ al ifi 4- 'A fi tvol. xxv, No. 1-4 and human infrastructure.

The Japanese, not only in the economic community but also in the street, generally believed in these types of theory of economic development because these theories were successfully applied in the economic development of Japan after the Meiji Restoration in 1868. And again these theories were successfully adopted after the World War II when the Japanese economy badly needed to re- build herself.

A very important fact is that, as I explain later, the Japanese government and business commun- ity applied this familiar theory for them to their ODA policy and practice in the developing world.

And so long as the Japanese ODA proved to be beneficial to the economic development of develop- ing coutries, the Japanese did not question about thier wisdom to apply their beloved economic theories for their ODA policy and practice.

Now I would like to explain about this in more detail.

In the beginning of economic development of the Meiji Restoration, the Japanese government tried to build what we call the economic and human infrastructure like railway lines, post office

networks and compulsory education system and so on. Also by using governmental imvestment, Japan could have many of leading industrial sectors like the textile industry, the iron & steel in- dustry and the ship-building industry.

However we should remember that, in this beginning of economic development of the Maiji era, Japan was one of the developing countries in the Far East. While the Meiji government energetical- ly tried to change Japan from a feudalistic society to a capitalist economy, it was not an easy task.

When the Meiji government tried to introduce the compulsory primary education system, many peasants resisted against the government order to send their sons and daughters to the primary schools because their children were indispensable labor force for their rural works.

When the central government in Tokyo began to make a detailed map of all Japan, the survey teams of the government were forced to employ interpreters to understand the local dialect in re- mote mountainous areas.

When the Meiji government established their first modern textile factory in a rural town not so far from Tokyo, the factory faced quite unbelievable situation to recruit young women workers.

The reason was that technical advisors of the factory who were Westerners employed by the gov- ernment used to drink red wine for their lunch and dinner. This Western custom produced a rumour that the Westerners were drinking blood and made young ladies around the factory so ter- rified. To solve this unexpected labor problem, the Maiji government ordered their officials who were former warriors or Samurai during the Tokugawa era to send their daughters to the textile factory. Thus the first modern textile industry in Japan could start.

These stories tell us that Japan in the early period of Meiji era was a developing country who

November 1996 Eiichi Imagawa : Theory and Practice of Japanese ODA27 was lacking of both industrial and human infrastructures.

The Meiji government could successfully change their developing country into a capitalist in- dustrial economy by their energetic involvement into economic development . With this process of economic modernization, dozens of big private companies have grown to lead a capitalist economic development of Japan. With big merchants who could survive from the Tokugawa Dynasty , many of former samurais or warriors could change themselves into capitalists who led this industrializa- tion of Japan.

Thus a theory that economic development could be attained by industrialization which was led by capitalists who were assisted by a clever government proved to be useful by this experience of the Meiji Japan. And also the experience of the Meiji revolution tells us an importance of building of infrustructure both in the industrial and human. These memory of the economic development of Japan during the Meiji period was firmly imprinted in the heart and mind of the Japanese. Then it is natural that Japanese economic leaders with their memory of the Meiji era and a theory of eco- nomic development derived from that period tried to apply the theory to their ODA policy and practice when they found themselves in a position to assist the present developing countries in the world.

Bisides from their memory of the Meiji Restoration, the beloved theory for the economic de- velopment by the Japanese was again confirmed in more recent history of Japan.

After the World War II Japan found herself in an economic ruins. The Japanese government who controlled the Japanese economy during the war was forced to give up their authority to the Allied Occupation Forces. The leading enterprises lost their capital and industrial facilities . The big landlords in rural areas were ordered by the Allied Forces to submit their lands to landless poor farmers. The labor movement was so violent in the midst of hyperinflation . Many leaders in the government and bussiness regarded as responsible for the war were expelled from their former positions. The result was a total confusion.

To save starvation, scarcity of materials, hyperinflation and total collapse of social order , natur- ally it became necessary to reestablish a kind of economic control system by the government of Japan.

To serve the purpose, in August 1946, the Headquarters for Economic Stabilization was estab- lished under the direct control of the prime minister of Japan . This Economic Stabilization Head- quarters led recovery of the Japanese economy by planning production, distribution of materials and also by controlling price of goods as well as finance and "transportation. Especially since the beginnings of 1947, by introducing "The Priority Production System" which has given a top prior- ity to a recovery of the iron & steel and the coal industries by intensively investing capital and materials into these two key industries, the Japanese government tried to stimulate an increased

28 t piVol. XXV, No. 1-4 production of all other economic sectors.

Thanks to these economic policies, until the end of 1940's economic situation of Japan began to be stabilized. Big private companies began to regain their powers and at the same time, the Japanese government also could retain a strong power for economic management by the success of the above mentioned economic recovery policies.

This economic experience of the post-World War II period again boosted for the Japanese the importance of an economic theory in which industrialization could be attained by efforts of capital- ist groups who were assisted by a clever government. And also the success of the Priority Produc- tion system gave the Japanese a strong impression of an importance of economic planning by the government, especially of setting key economic sectors in an economic development planning.

Thus, in conclusion, we can say that, through the experience of the Meiji Restoration and the World War II, the Japanese could learn their basic theory of economic development in which these several points were very important. They were as follows: No.1; the importance of industrializa- tion led by capitalist groups who were assisted by clever government. No.2; the importance of building of economic and human infrastructure in the beginning of economic development. No.3;

the importance of setting a priority among the economic sectors to which we wish to develop.

And as I mentioned before, the Japanese applied their economic theory to their practice of the ODA. Now I would like explain about this.

III: The Practice of the Japanese ODA

The Japanese ODA policy gives a strong emphasis on policy initiatives by governments of reci- pient countries. It is ruled that the Japanese government decides their ODA projects by the request of governments of the recipient countries. When governments of developing countries wishes to re- cieve Japanese ODA, they are asked to present their plans or projects to the Japanese government and to explain the necessity of their plans or projects for their economic development. In this pro- cess, the Japanese government is supposed not to present their own plans or projects to recipent countries.

This decision-making process of the Japanese ODA which we used to call "A Principle of the Re- quest by the Recipient Country" clearly shows that the Japanese prefers to see a situation in which a government in a developing country strongly exercises their policy initiative in an economic development of a country.

We can also say that this emphasis on the governmental initiative in an economic development derives from the above mentioned theory of the economic development in Japan which was estab- lished through the Japanese experience of the Meiji Restoration and the World War II. That is, the Japanese likes the economic development guided by a clever govenment.

November 1996 Eiichi Imagawa Theory and Practice of Japanese ODA29

In their ODA policy, the Japanese government also strongly emphasizes the importance of build- ing economic and human infrastructure in an earlier stage of economic development of developing countries. This emphsis on the infrastructure clearly derives from the above mentioned Japanese experiences of economic development in the Meiji era and the post-World War II period. At the same time, this emphasis on infrastructure shows the fact that the Japanese regards the indus- trialization as an universal goal of economic development in any of the developing countries. That

is to say, the Japanese believes that a building of both economic and human infrastructure is an in- dispensable first step to attain an industrialization of any developing country.

When we see the record of the Japanese ODA, it is not difficult to find out a fact that the Japanese always tried to provide economic assistance for the building of economic and human in- frastructure in their first stage of ODA to almost all of developing countries . This means that Japan's goal of ODA to developing countries was to assist the industrialization of those countries.

Now I would like examine the practice of Japanese ODA in their relation with the assistance for infrastructure building.

After attaining substantial economic recovery by the economic boom during the Korean war in the early 1950's, Japan began to increase her export and private investment to foreign countries, especially toward Southeat Asia and Taiwan.

In this period of later 1950's to early 1960's, the Japanese economic assistance to the develop- ing countries was still so small amount, though India was given the First Yen Credit in 1958 . However in the context of the Japanese ODA, it is important to remember that, in this period, Japan began to pay her wartime reparation payment to some of Asian countries, like Burma, the Philippines, Indonesia and South Vietnam. The total amount of the payment promised was about one billion US dollars. The reparation treaties were signed by Japan with each countries between

1955 and 1960, and all payment was scheduled to be completed by 1976 .

The reparation payment was important in view of Japanese economic assistance policy with a great emphasis on infrastructure building, because main part of reparation payment was used for big project to build infrastracture like Hydroelectric dam. Needless to say, this emphasis on the in- frastructure building was followed by succeeding Japan's ODA projects.

During 1960's, stimulated by an economic boom which was brought about by the Vietnam war , Japan's export and investment toward Asia, especially to Southeast Asia increased dramatically. In this period, too, the Japanese ODA began to increase.

For example, between 1966 to 1970, the Japanese ODA to Southeast Asia and East Asia amounted to about US dollars 1.6 billion. Main portion of which was the Yen Credit to build the infrastructure like dams, power stations and so on.

However, a rapid increase of the Japanese economic presence in Asia , especially in Southeast

30 pkVol. XXV, No. 1-4 Asia, began to invite some Anti-Japanese feelings in this area since late part of 1960's to early 1970's. These uneasy feelings against Japan culminated in the anti-Japanese demonstrations and riots in Bangkok and Djakarta in early 1974 when Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka visited there.

To calm down this anti-Japanese feeling, the Japanese government tried to increase her import from Southeast Asia to reduce trade surplus with the area, and also tried to expand her economic assistance to the region. For example, the total of the Japanese ODA toward Southeast and East Asia between 1971 and 1975 amounted to about US dollars 3.4 billion as compared with US dol- lars 1.6 billion of between 1966 and 1970. The total Japanese ODA to the same region between 1975 and 1980 jumped to about US dollars 7.1 billion.

This big increase of the Japanese ODA during later part of 1970's partially reflects the fact that, since 1979, Japan began to provide her ODA to China to assist her economic modernization.

The Japanese ODA continued to increase during 1980's and after. For examples, the total Japanese ODA between 1981 and 1985 amounted to about US dollars 18.1 billion. Again the ODA between 1986 and 1990 reached to about US dollars 40.3 billion. And the ODA of four years between 1991 and 1994 amounted to about US dollars 46.5 billion.

However, in spite of this increase of the Japanese ODA, the Japanese emphasis on the infrastruc- ture building did not change almost at all.

"The annual ODA report 1995" by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan proudly proclaims that "Japan has extended cooperation to East Asian countries, seeking to achieve export-led econo- mic growth, by extending ODA loans to help them finance the construction of economic infrastrac- ture (highway systems and power generation facilities)."

According to the ODA Report, in 1994, 41.2% of the bilateral ODA of Japan was allocated to building economic infrastructure and 23.2% to projects to improve social infrastructure (e.g.educa- tion, public health, sanitation, and population). In total, nearly 65% of the Japanese ODA was used to build economic and social infrustructure in 1994 and the remaining 35% was used in the field of Basic Human Needs.

As I explained above, Japan emphasized her ODA to build economic and human infrastructure in order to assist industrialization of developing countries. When we look at the successful economic development of East and Southeast Asian countries who were recipients of the ODA of Japan, we might be able to say that the Japanese ODA was successful by paying special attention to the building of infrastructure of the recipient countries.

The importance of the Japanese ODA in the building of infrastructure of recipient countries is well understood by the following explanation of the ODA Report.

According to the ODA Report, the share of Power-Generating Facilities financed by Japan's ODA Yen Loans in the total power generating capacity of Thailand was 14%, especially in case of

November 1996 Eiichi Imagawa : Theory and Practice of Japanese ODA3i

total Hydroelectric Power-Generating Capacity , the share of Japanese ODA took 31%. In Indonesia, 20% of the total costs of construction of power generating capacity were financed by the Japanese Yen Loans. In case of Malaysia, the share of the Japanese ODA in the total construction costs of power generation capacity reached to 50%.

Besides the Power-Generating Facilities , in the field of transport and telecomunication, the Japanese ODA took high shares in the total expenditure of the recipient countries. For example, in Indonesia, 50% of the costs of construction of microwave cables across the country were financed by the Japanese ODA.

Thus, when we see the practice of the Japanese ODA in many of East and Southeast Asian coun- tries, we would be able to claim that the Japan's ODA which paid an special attention on the in- frastracture building could considerably contribute the economic development of the recipient countries.

However, in recent years, both in Japan and in some of the recipient countries , the Japanese ODA policy which has a special preference for the infrastracture building and also pays an special emphasis on initiatives by a government for economic development began to invite some severe cri- ticism.

I would like to explain about the reasons of this criticism against Japanese ODA policy .

IV: Challenges to the Japanese ODA Policy

The Japanaese ODA policy and its practice are inviting some critical comments in recent years both in Japan and in recipient countries .

Firstly, the preference by the Japanese ODA for the infrastructure building is criticized by the following reasons.

One reason is that, by the preference for the infrastructure building which is mainly consisted of big projects, the Japanese ODA tends to benefit only big business communities of both in reci- pient and donor countries and brings a result that wellbeing of ordinary people of the recipient countries is often neglected. The most simple criticism was that the Japanese ODA benefits only big business community in Japan.

Some critics also say that Japan's ODA is designed to benefit only Japan herself by numerous regulations to force the recipient country to order Japanese-made goods for the ODA projects .

It is true that building of infrastructure in one country does not contribute directly for raising the wellbeing of ordinary people in the near future . However, it is also true that by strengthening the infrastructure of one country, the country can expect an earlier result for their economic de- velopment which in the long run could benefit the wellbeing of the ordinary people . Thus, in spite of the criticism against the Japanese preference for the infrastructure , the Japanese government

32 fIJ ig Vol. XXV, No. 1-4 did not agree to change their main ODA policy that pays an special attention to infrastructure. In the above mentioned ODA Report, the Japanese government says that the Japanese cooperation in the improvement of basic economic and social infrastructure has contributed, with the development of trade and private investment, to the improvement of "the living standards of local inhabitant."

Toward the criticism that an main aim of the Japanese ODA is to give benefits to big business enterprises of Japan, the Japanese government rebuffs the criticism by claiming that Japan is rapidly increasing the untied portion of its ODA program. According to the ODA Report, the un- tied ratio which indicates the ratio of unrestricted part of ODA loans when purchasing goods and services increased to as high as 98.3% in FY 1994. Moreover, only 27% of the value of Japanese ODA projects were ordered to Japanese firms in FY 1994. In case of ODA projects by main adv- anced countries including the United States and Germany, more than 50% of the ODA projects were received by the companies of their own countries. Thus the Japanese government can claims that their ODA is not aimed to assist their big business.

The second criticism against the Japan's preference on the building of infrastructure is that the emphasis of Japan on building of big scale infrastructure is now becoming a kind of out of date de- velopment strategy. This criticism arose since late 1980', when, because of increasing shortage of financial resources in the developing countries, no small number of the developing countries began to prefer to reduce their investments in big projects. They began to show their preference for small scale projects like rural development and modernization of small-scale industries.

This change of development strategy in the development countries was an embarrassing one for the Japanese government who had a plan to increase aggressively their ODA disbursement toward developing countries.

For example, the Japanese government has established a plan to disburse U.S.$ 21,360 million as their total ODA for the period of between 1981 and 1985. However, the actual amount of dis- bursement was U.S.$ 18,071. A main reason of this failure to attain the goal was the reduced de-

mand from developing countries for big infrastructure projects.

In spite of this failure, on September 1985, the Japanese government decided to expand her ODA between the period of 1986 and 1992 to the total of more than U.S.$ 40,000 million. This goal of the Japanese ODA was revised upwardly on May of 1987 when the Japanese government decided to attain the goal of U.S.$ 40,000 million within five years instead of seven years from 1986.

The Japanese government decided to increase her ODA goal mainly because of Japan's excellent economic performance in the period of mid-1980's. For example, the foreign currency reserves of Japan expanded from U.S.$ 26,519 million in 1985 to U.S.$ 42,239 million in 1986 and to U.S.$

81,479 million in 1987. One reason of this increase of the Japanese foreign currency reserves

November 1996 Eiichi Imagawa : Theory and Practice of Japanese ODA33

was that the Bank of Japan bought a lot of U.S.dollars to support the dollar value against the Japanese Yen which began to increase rapidly in its value after the Plaza agreement of September 1985.

Fortunately, for the period of between 1985 and 1990 , the Japanese government could attain their ODA goal of U.S.$ 40,000 million with the result of U.S.$ 40 ,300 million. However, for the period of between 1986 and 1990, the yen value against the U.S.dollar increased from Y200 to a U.S.dollar at the last day of 1985 to Y135 to a U.S.dollar on December 31st of 1990. During this period, the Yen once recorded Y120 to a U.S.dollar on December 31st of 1987. This increased Yen value means that Japan clearly could not attain her goal of ODA disbursement for this five- year period if we calculate it in the Yen term.

For example, U.S.$ 40,300 million mean Y8 ,060,000 million, if we calculate it by using a rate of Y200 to a U.S.dollar which was the rate of December 31st of 1985 . However, the actual amount of the Japanese ODA for the period of between 1986 and 1990 in Yen basis were Y5,770,300 million. Though if we use the rate of Y140 to a dollar which was the rate of May 1987 when the Japanese government decided new goal of ODA, U.S.$ 40,300 million mean Y5,642,000. In this case, Japan could barely attain her ODA goal. If we use the rate of Y144.81 to a dollar which was the average rate of the Yen to a dollar for the five year period of between

1986 and 1990, U.S.$ 40,300 mean Y5,835,438. In this case , Japan could not attain her ODA goal.

Fortunately again, Japan could expand her ODA for the four-year period between 1991 and 1994 with the total amount of U.S.$ 45.5 billion from U.S.$ 40.3 billion of the previous five years. However, the Yen value to the U.S.dollar again increased for this four-year period from Y131 to a U.S.dolar on January 4th of 1991 to Y96.68 on October 21st of 1994 . This means that the real increase of Japanese ODA in Yen basis is not so high as in a dollar basis .

According to the ODA Report, over the ten-year period from 1984 to 1994 , Japan's ODA showed a 32% increase in yen value, compared with a 207% increase on a dollar basis .

It seems to me that this slow increase of the Japanese ODA in a Yen basis during ten years be- tween 1984 and 1994 considerably reflects the weak demand for infrastructure projects in de- veloping countires. The fact that a nearly 60% of the ODA of Japan is consisted of the project in the field of economic and social infrastructure means that , so long as this weak demand for the project in the field of infrastructure continues, it might be difficult to increase drastically the Japanese ODA in the near future.

The difficulty to increase the Japanese ODA in the field of infrastructure becomes more clear when we lool at recent practice of ODA in the field of Bilateral Loans which provide main portion of Japan's ODA to build infrastructure. The Bilateral Loans reached to a peak of Y736 ,400 mil-

34 ~i1 Avol. xxv, No. 1-4 lion in 1991. However it decreased consecutively next two years to Y585,200 million in 1992 and to Y394,000 million in 1993. Though the figure increased to Y435,221 million in 1994, this is not a satisfactory figure if we compare with the annual average of Bilateral ODA Loans in the period of between 1986 and 1990 which was Y466,600 million.

This slow or stagnant pace of increase of the Japanese ODA whose responsibility is mainly in the Bilateral Loan program is the second reason why the preference of Japanese ODA for the in- frastructure project is being criticized.

Here comes the third criticism against the Japan's preference on the infrastructure project. This is that because of increased concern in the world for gloval environment, it might become in- creasingly difficult to find a big scale project suitable for the Japan's ODA. In fact, some of Japan's ODA project have beeen and are inviting protests from the local people who are afraid of worsen- ing of environment in their living areas because of the ODA projects like Dam construction.

Besides these criticism on Japan's ODA policy concerning preference for infrastructure, Japan is forced to reconsider her traditional ODA policy for another reason.

As I explained above, the Japanese ODA policy has put a special emphasis on initiative for eco- nomic development by the government of recipient countries. However, during 1980's, especially

after the collapse of the Soviet economic system under the Gorbachev regime, an appreciation on the role of the government in economic development began to decrease rapidly in allover the world. The Privatization became a top slogan to enhance economic development not only in the capitalist but also in the socialist countries. So in many of developing countries, role of the govern- ment or governmental organization in their economies begans to lose their influence. Even in the project to build economic infrastructure, private companies, not the government, began to take in- itiatives.

Because of this new trend of privatization, the Japanese government was forced to revise their policy to put emphasis on the governmental initatives. To finance the Japanese ODA not only to governments of developing countries but also to private companies for private projects became necessary.

V: In Search for New Theory of the Japanese ODA

Facing with increasing challenges against the Japanese ODA policy and practice as I mentioned above, the Japanese government, in recent years, began to revise her ODA policy to meet the new situation in developing countries and also in the world politics.

In the first place, to cope with the criticism against the Japanese preference for the big infras- tructure projects, the Japanese government began to put an increasing emphasis on the projects like environment protection, population, health, support for market-oriented economies and finan-

November 1996 Eiichi Imagawa : Theory and Practice of Japanese ODA35

cial support for LDCs. And these assistance were mainly given as Bilateral Grant Aid in the form of financial assistance and technical cooperation.

Since the mid-1980's, because of reduced financial resources in many developing countries , de- mand for the commodity loans to import goods and needs for fund to finance the rural develop- ment or development of small-scale industries increased . At the same time, the Structural Adjust- ment Lending (SAL) with the purpose to improve effectiveness of economic development policies , also began to increase.

And again, during the first half of 1990's, besides of these demand for financial assistance , aid requests for poverty relief, environment protection , emergency humanitarian relief for war victims, health and population were constantly increasing. Assistance to the countries in transition to market-oriented economies also increased .

Because of expanded demand for these aid items other than Bilateral Loans in developing coun- tries, share of Bilateral Grant Aid in Japanese ODA began to increase rapidly since the beginning of 1990's.

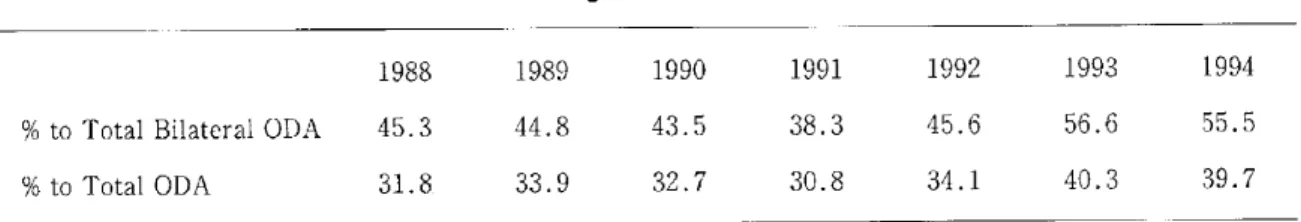

For example, the share of Bilateral Grant Aid in total Japanese ODA increased from about 31%

in later half of 1980's to nearly 40% in 1993 and again in 1994 . At the same time, the share of Bilateral Grant Aid in total Bilateral assistance increased from about 44% in the later half of 1980's to more than 55% in 1993 and also in 1994. Needless to say , this increase of Bilateral Grant Aid means the decline of amount of Bilateral Loans which are used for infrastructure pro- jects.

However, in spite of the declining share of Bilateral Loans , Japan did not change her traditional ODA policy which put emphasis on the infrastructure projects .

The main reason of this preference for the infrastrucuture projecs by the Japanese government is, in my opinion, that the Japanese still believes in their theory on economic development which is derived from their experience of the Meiji Restoration and the Post World War period .

The second reason for Japanese insistence on their traditional ODA policy is that there is still a lot of demand for the Japanese Bilateral Loans from many of developing countries. Especially , countries like China and Indonesia who are main recipients of Japanese ODA prefer to receive Bi- lateral Loans from Japan to use them for their vast need of economic infrastructure.

The third reason for Japan's reluctance to reduce her preference on the infrastructure projects is that if Japan decides to do so, the total amount of Japan's ODA might begin to decrease so rapid- ly that Japan could not keep her promise to the world that she will try to increase her ODA steadily.

Because of these reasons Japan still put emphasis on the expansion of her Bilateral Loans to the developing countries.

36 IJ "iJ ffi 4 'A aVol. XXV, No. 1-4 However, in spite of Japan's insistence on the Bilateral Loans, it is clear that the share of Bi- lateral Loans in total Japanese ODA began to decline in recent years. Then if Japan wishes to in- crease her Bilateral Loans, there should be some new ideas or policies to prevent the recent trend of declining share of the Bilateral Loans in her ODA.

Now I would like to examine some of these new ideas or policies.

When we examine the content of the Japanese Bilateral Loans, we can easily find a specific char- acteristic in its practice. This is the fact that a few Asian countries occupy a large portion of Japanese Bilateral Loans.

For example, in 1994, China, India, Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand occupied nearly 74% of the disbursement of Bilateral Loans of Japan. In 1993, the same five big receipients of Japanese ODA received nearly 82.5% of the Bilateral Loans. In both two years, China were top re- ceipients and followed by India in 1994 and by Indonesia in 1993.

When we examine about the practice of Japanese Bilateral Loans, at the first point, we must pick up this issue of monopoly of Bilateral Loans by big five receipient countries. It seems to me that these five Asian countries who have comparatively large population were considered by the Japanese as most suitable model of economic assistance for export-oriented idusrialization of de- veloping countries. Then a kind of concentration of Japanese ODA Loans on these five countries has resulted.

However, when we consider new policies to increase the Bilateral Loans, we must question ab- out this concentration of our ODA Loans on these five countries. For example, we might be able to say that so long as we continue to depend upon these five countries for our main receipients of ODA Loans, it might be difficult to increase the ODA Loans considerably because a kind of monopoly by these five countries is already being criticized.

Then comes the second question that when we could not increase our ODA Loans to these five countries any more, whether it is possible to increase it to other developing countries. I think that it is possible. Japan has contributed a considerable amount of ODA Loans to countries like Pakis- tan, Bangladesh, Egypt and Mexico. Then Japan can increase her ODA Loans to the countries in West Asia, Middle East, Latin America and Africa. In these regions other than East and Southeast Asia, there are many countries who have big population and land space and need the development of social and economic infrastructure.

Even within Asia, there might be some countries other than big fives where Japan might be able to increase her Bilateral Loans.

Japan could be able to increase he ODA Loans to Vietnam where the export-oriented indus- trialization is developing so rapidly. Japan is carefully preparing to resume her ODA to Myanmar where we can see a fast fevelopment for a market-oriented economy.

November 1996 Eiichi Imagawa : Theory and Practice of Japanese ODA37

There are some other interesting countries for the Bilateral Loans in Asia. They are Laos and Mongolia. Though these two countries have large land areas, their population are so small. Mongo- lia has about 2.5 million and Laos has 4.5 million. Both Mongolia and Laos are receipients of the Japanese Bilateral Loans, however their shares within total Japanese Bilateral Loans in recent years were less than 0.1%.

From the Japanese point of view of economic development which put a special emphasis on export-oriented industrialization, a country who has a small number of population is regarded as a country who is not fit for the export-oriented industrialization, because of her lack of ample labor force. A small number of population also means a small internal market in the country so that it is considered as a difficult task even to build import-substitute industries.

Then a country who has a small number of population usually does not become a big receipient of the Japanese Bilateral Loans whose purpose are to build economic infrastructure to support the industrialization of a developing country.

For example, Laos once received a Japanese Bilateral Loan to build a Hydroelectric darn. Howev- er Laos's internal demand for the electric power could not reach the total electric power produc- tion from the dam, because of a low level of industrialization and urbanization of the country.

Then Laos decided to export the electric power from the dam to Thailand who was her neighbor.

Thailand who was experiencing a rapid industrialization was also lacking of enough supply of electric power, then this trade of electric power proved to be beneficial for both two neighboring countries. Then, in recent years, Laos again established a plan to build several hydroelectric dams in their country and to export the electric power from the dams to Thailand and asked Japan to provide the Bilateral Loans for those dam projects.

However, for Japan, so long as she regards the hydroelectric dam as a precondition of indus- trialization of Laos herself, to support a dam construction whose sole purpose is an export of elec- tric power was a troublesome question. In this case Japan replied to Laos that Japan would consid- er the proposal positively. Though the Japanese government does not yet explain their position in this case, I can suppose that Japan is favorable of this Laosian project because the dam construc- tion could be beneficial for the economies of both Laos and Thailand, especially for the export- oriented industrialization of Thailand.

This Laosian case suggests for us that if Japan could look at her cooperation on the indus- trialization of a country from a wider view that includes economic development of neighboring countries, it might become possible for Japan to increase her Bilateral ODA Loans even to a coun- try with a small number of population.

Again Laos who is surrounded by several countries like China, Vietnam and Thailand could be able to develop transport and communication networks with her neighbors and to raise some be-

38 T1IJ fE { a Vol. XXV, No. 1-4 nefits through these imporoved networks. In this case Japan could extend her ODA Loans to Laos through the projects like the constructuion of bridges across the Mekong river and the improve- ment of road networks in Laos.

When the economic result of one project affects favorably on several countries like the case of improvement of transport networks in Laos, Japan might be able to extend her ODA Loans to a group of countries who could become beneficiaries from the project.

In case of Japan's ODA Loans to Mongolia, so for Japan provided loans to improve railways sys- tem and electric power generation for the country. The purpose of these assistance is to support basic economic and social infrastructure, rather than to aid an industrialization of this country.

When we consider the small number of population of Mongolia, the scope of development of export-oriented industrialization in this country is limited except for some specific industries like cassimere industry.

Then the scope of Japanese Bilateral Loans to this country is also limited. However, in case of Mongolia who has a large land area with a small number of population, a goal of economic de- velopment of this country should not be an export-oriented industrialization but should be an eco- nomic development without much dependence upon industrialization. Agriculture including animal husbandry which is combined with some rural industries and sightseeing industry could lead an economic development of this country. To assist a kind of non-industrial economic development of Mongolia, Japan will be able to provide her ODA Loans to the projects like an improvement of commercial transportation networks in rural areas to support agricultural industries as well as sightseeing industry.

Thus, by expanding Japan's Bilateral Loans to the countries other than "Big Fives" recipient countries in Asia, and also by exploring new needs for Japanese loans, Japan could be able to maintain a present level of the Bilateral Loans and if possible to increase her bilateral Loans to the level of a later half of 1980's.

However, as stated above, the policy and practice of Japanese ODA are forced to change since the middle of 1980's. Especially, Japan's Bilateral Loan which was a core of the Japanese ODA is now reducing its share in the total ODA because of rapid change of international economic and political situation.

To cope with this change of policy and practice of Japanese ODA, Japan should also reexamine her theory on ODA policy. As mentioned above, Japan's theory on her ODA was to stress the im- portance of infrastructure building as precondition of export-oriented industrialization of a de- veloping country. Japan also emphasized the importance of governmental initiatives and guidance in the economic development.

In recent years,however, an importance of Japan's Bilateral Loan which was a main source of

November 1996 Eiichi Imagawa : Theory and Practice of Japanese ODA39

Japan's ODA to finance the infrastructure building began to decrease while Bilateral Grant Aid in the form of financial assistance and technical cooperation began to increase . The Bilateral Grant Aid was mainly used as commodity loans for poor countries and technical aids in the field of education, environment protection, health and so on. And again, mainly because of the collapse of the Soviet economic system, the importance of government initiatives in the economic development began to decrease and Japan is obliged to pay an more attention on the private initiatives on the economic development.

These new development concerning Japanese ODA requires a new theory to justify the present Japanese ODA policy and practice. Japan's stress on the socio-economic infrastructure still would be a right theory because at the start of economic development all countries need to build some ex- tent of socio-economic infrastructure. However, Japan's stress on the export-oriented industrializa- tion should be a little bit revised. Because if Japan continues to emphasize an importance of export-oriented industrialization, only countries who have a comparatively large number of population could become beneficiaries of Japan's ODA, especially of the Bilateral Loans. Japan should admit multiple ways to the economic development according to the various types of de- veloping countires. The economic development without much dependence on export-oriented indus- trialization is posible and Japan could extend her ODA for this kind of economic development .

Japan's stress on the governmental initiatives in the economic development also should be re- vised to admit more private initiatives.

Thus, when we consider a new economic theory for Japan's ODA , we can have a theory in which we continue to stress on the importance of infrastructure but do not emphasize the industrializa- tion, especially export-oriented one , as a goal of economic development nor stress on the import- ance of governmental initiatives.

On June 30, 1992, the Japanese government adopted a new policy statement on their ODA in which Japan stressed the importance of Humanitarian considerations as a basic philosophy of her ODA and also declared her intention to refrain her ODA from those counties who were increasing their military expenditure and also did not promote democratization of their countries .

But this policy statement did not mention about the economic theory of Japan's ODA in a new world. This means that Japan still maintain her ODA theory that emphasizes the infrastructure building as a precondition of export-oriented industrialization which is guided by government .

40

Table 1 : Amount of the Japanese ODA

Vol. XXV, No. 1-4 (Million Yen)

Bilateral Grant Bilateral Loan Total ODA

1990 437 567 1,335

210 639 328

1991 456 736 1,484

600 447 023

1992 489,492

585,205 1,435,417

1993 513 393 1,275

715 997 687

1994 542

435 1,364

028 221 419

Table 2

(Source:IDE, Handbook of Economic Cooperation

: Increasing Shares of Bilateral Grant

, 1995)

(%)

% to Total Bilateral ODA

% to Total ODA

1988 45.3

31.8

1989 44.8 33.9

1990 43.5 32.7

1991 38.3 30.8

1992 45.6 34.1

1993 56.6 40.3

1994 55.5 39.7

(Source: IDE, Handbook of Economic Cooperation, 1995)

Table 3 : 5 Largest Recipient Countries of Japan's ODA Loans

(Million $)

China India Indonesia

Philippines Thaiand

Total 5 countries (%) Total ODA Loans

1993 1,051

247 923 513 190 2,925(82.5) 3,544

1994 1,133

828 636 343 218 3,158 (74.2) 4,257

(source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Anuual ODA Report)