A study on the effects of growing up in a family with DV on children with a cross-cultural background: field research from a maternal and child living support facility

全文

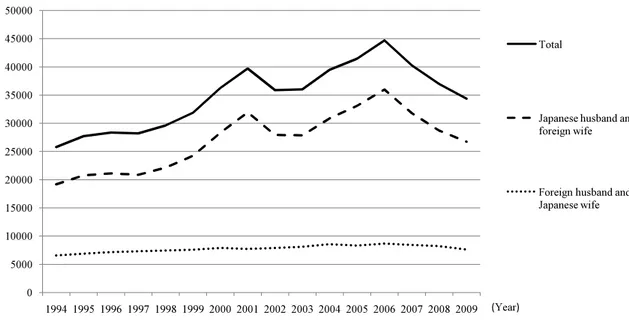

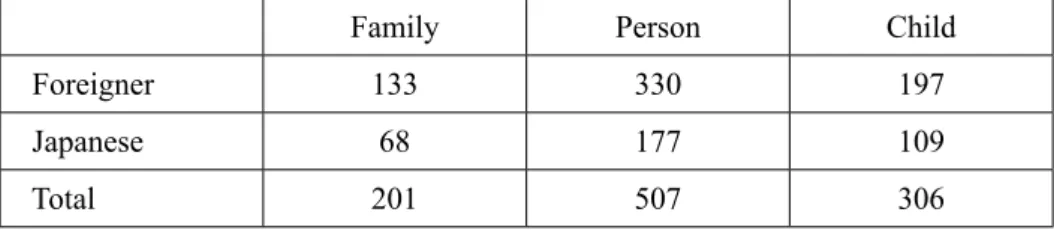

図

関連したドキュメント

Banana plants attain a position of central importance within Javanese culture: as a source of food and beverages, for cooking and containing material for daily life, and also

When attempting to communicate with parents of children with special care needs, childcare workers faced difficulties in such aspects as Lack of professional skills on the

The collected samples in this study may not have been representative of conditions throughout Cambodia be- cause of the limited area of sample collection, insufficient sample size

Required environmental education in junior high school for pro-environmental behavior in Indonesia:.. a perspective on parents’ household sanitation situations and teachers’

The aims of this study were to explore the trends in research on support for the siblings of children with diseases/disabilities and discuss future challenges related to this topic.

Research in mathematics education should address the relationship between language and mathematics learning from a theoretical perspective that combines current perspectives

An example of a database state in the lextensive category of finite sets, for the EA sketch of our school data specification is provided by any database which models the

Eskandani, “Stability of a mixed additive and cubic functional equation in quasi- Banach spaces,” Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications, vol.. Eshaghi Gordji, “Stability