は じ め に 21 世紀に入り,医学の分野においては治療医学のみ でなく予防医学についても重要視されてきており,これ に加えて近年における薬剤耐性細菌の出現もあり,これ までの抗生物質に代わってプロバイオティクスやプレバ イオティクスといった腸内細菌叢に関与しながら宿主の 健康の維持増進を図ろうとする物質が開発されてきてい る.これも近年における高度嫌気性菌の培養技術の確立 や分子生物学ならびに免疫学などの研究が進展し,その 結果として腸内細菌叢の構成や機能(存在意義)が徐々 に解明されてきたからにほかならない.腸内細菌叢の生 態や機能の解明には腸内に存在する細菌の種類や数を正 確に把握することが必要十分条件であるゆえ,より精度 の高い腸内細菌叢の検索法の確立のためにこれまで数々 の方法が考案され,目覚しい進展を遂げてきた.腸内細 菌叢を構成する多く(100 ∼ 500 種類)の菌種・菌群が示 されている中で Bifidobacterium ならびに Lactobacillus はその生態や機能に関する研究が多くの研究者によって 実施されており,有用作用を示す細菌であることが明ら かにされているが,他方において生態や機能はおろか, 培養による分離すらなされず遺伝子のみで検出される種

腸内細菌検索法の変遷と現状

―培養法からメタゲノム解析まで―

藤澤 倫彦

*,大橋 雄二

* 日本獣医生命科学大学応用生命科学部食品衛生学教室Progress and Present Status of Methods for the Analysis of Intestinal Microbiota

—From Cultivation to Metagenome Analysis—

Tomohiko FUJISAWA*, Yuji OHASHI

*Department of Food Hygiene, Faculty of Applied Life Science, Nippon Veterinary and Life Science University

要 旨 健常なヒトや動物の腸内には多種多様な細菌が存在している.これら細菌の生態や機能についての検討を行うに

当たっては精度の高い検出法を用いることが基本である.現在まで,これら細菌叢を検索するための EG 寒天培地や BL 寒 天培地といった非選択培地および種々の高感度選択培地,ロールチューブ法,嫌気性グローブボックス,Plate-in-bottle 法 といった腸内に優勢に存在する高度嫌気性細菌検出のための手段が開発されてきた.一方,近年における分子生物学の進 展に伴い,FISH 法,PCR 法,クローンライブラリー法,DGGE 法,TGGE 法,T-RFLP 法,メタゲノム解析といった細菌 遺伝子をターゲットにした腸内細菌叢検索法も用いられてきている.本稿では,腸内細菌叢検索手技の歴史的変遷と現状 についてその概略を述べた.

Abstract Many different kinds of bacteria are normally found in the intestines of healthy humans and animals. To study the ecology and function of these intestinal bacteria, the culture method is the basic technique. Suitable agar plates such as non-selective agar plates (BL agar and EG agar) and several selective agar plates have been developed. Furthermore, the roll-tube, glove box, and plate-in-bottle methods have also been developed for the cultivation of fastidious anaerobes which predominantly colonize the intestine. In addition, genomic analyse such as the FISH method, the PCR method, the clone-library method, the DGGE/TGGE methods, the T-RFLP method and metagenome analysis have been used for the investigation of intestinal microbiota in recent years. This paper summarizes the progress and present status of the meth-ods of analysis for intestinal microbiota.

Key words: analysis of intestinal microbiota ; culture method ; plate-in-bottle method ; fastidious anaerobe ; genomic

analysis

腸内細菌学雑誌 25 : 165–179,2011

2011 年 5 月 30 日受付

*

〒 180–8602 東京都武蔵野市境南町 1–7–1 1–7–1, Kyonan-cho, Musashino-shi, Tokyo, 180–8602, Japan

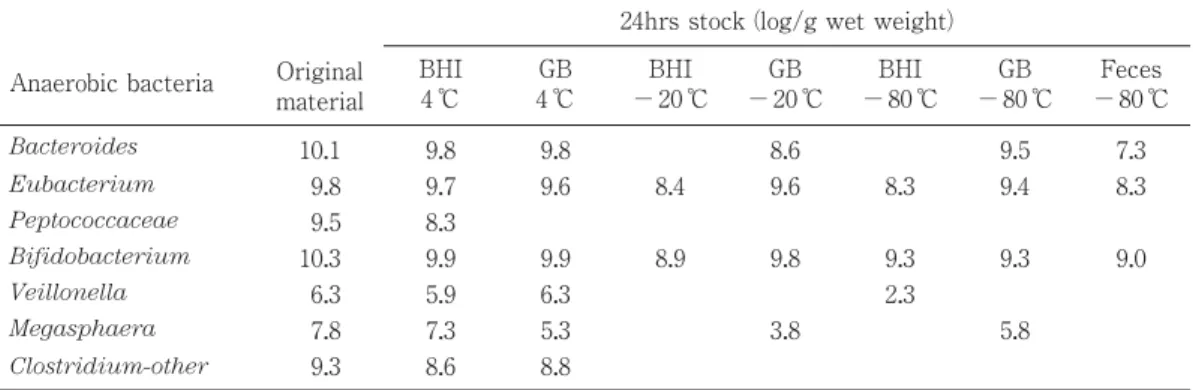

類も多々ある.このなかには有用性や有害性を示す細菌 が含まれている可能性もあり,腸内細菌の宿主におよぼ す影響を解明するに当たっての大きな障害であることは 間違いのない事実である.ここではこれまで検討・考案 されてきた腸内細菌叢の検索手技について,培養法から 分子生物学的手法を用いた方法に至るまでをその歴史的 変遷を辿りながら概略を述べる. 培養法による腸内細菌叢の検索 検体輸送法の検討 腸内容物や糞便などの検体は採材後可能な限り迅速に 処理することが望まれるが,やむを得ず即座に処理が不 可能な場合や採材場所と異なる検査機関に輸送して検査 を実施しなければならない場合には手段を講じる必要が ある.基本的には検体を適当な輸送培地に入れ,嫌気的 条件下で細菌が死滅あるいは増殖しない温度(4 ℃)で 保存,輸送する.しかしながら,細菌の種類によって, 特に嫌気性グラム陽性球菌などは比較的早く不検出とな るので,短時間であるほど好ましい.一方,凍結保存を 勧める報告もあるが,凍結は決して好ましい保存法では ない.Table 1 には主な嫌気性細菌における光岡が考案 したブレインハートインフュージョン培地にシステイン と寒天を加えた嫌気性の輸送培地(1)と GB 培地(2) との生残性の比較(3)を示す.光岡の輸送培地を用い, 4 ℃での保存が最も優れていることから,これまで腸内 細菌叢の検索に多用されている. 直接塗抹検査による菌数検索 検体中の菌数を簡易的に算出する方法として古くから 用いられて方法である.検体を 10− 1∼ 10− 3に希釈し, それをガラス鉛筆で 1 cm 四方の正方形が書かれたスラ イドガラス上にそれぞれ 0.01 ml ずつ採り,白金耳で一 様に塗抹し,グラム染色または単染色を行い,染色され た細菌を計測し,検体重量当たりの菌数を算出するもの ある.数視野について検鏡し,1 視野当たりの平均菌数 を N,視野の直径を d(mm)とすれば,観察した希釈 液 1 ml 当たりの菌数は N × 4 × 104/ πd2で算定される. 本方法で得られるデータには生菌の他,死菌の菌数も含 まれるので,算出される値は総菌数である.菌の種類は グラム染色による染色性,菌形態,芽胞の有無などでの 判定である(4).van Houte & Gibbons(5)によるとヒ ト糞便 1 g 当たり 3.2 × 1011(1.0 × 1011∼ 6.3 × 1011)の 細菌が観察されることが示されているが,この中には死 滅しているものも含まれると思われる.当初,特に嫌気 性菌の培養技術が不完全であった時代において,培養に より生育してくる細菌数と直接塗抹検査法による菌数の 間に大きな隔たりがあったことから,観察される細菌の ほとんどは死滅しているものとみなされた. 嫌気培養法の検討 腸内に嫌気性菌が多数存在することが示されたのは 1930 年代(6, 7)であるが,詳細な菌数の把握は 1960 年 代になってからである.1800 年代の終わりから 1900 年 代前半は主として嫌気性菌の発育に適した培地の改良や 嫌気ジャー法の開発に関して多くの報告がある.各種還 元剤(アスコルビン酸,チオグリコール酸,システイン など),酸化還元電位を考慮したクックドミート培地, チオグリコール酸培地の使用,煮沸・急冷による脱気等 の手段,また,アルカリ・ピロガロール法,スチールウ ール法,黄燐法などによる嫌気ジャーを用いる手段であ る .こ れ ら の 方 法 を 用 い て 1960 年 代 に van Houte & Gibbons(5),Smith & Crabb(8),Smith & Jones(9), Mata ら (10),Schaedler ら (11),Haenel & Müller-Beuthow(12),Gorbach ら(13),Zubrzycki & Spaulding (14),Mitsuoka ら(15)は精力的な検討を行い,腸内 に存在する細菌の種類や菌数が大枠で示された.一方,

Table 1. Comparison of transport methods for survival of some fecal anaerobesa (3).

Anaerobic bacteria Original material

24hrs stock (log/g wet weight) BHI 4 ℃ GB 4 ℃ BHI − 20 ℃ GB − 20 ℃ BHI − 80 ℃ GB − 80 ℃ Feces − 80 ℃ Bacteroides 10.1 9.8 9.8 8.6 9.5 7.3 Eubacterium 9.8 9.7 9.6 8.4 9.6 8.3 9.4 8.3 Peptococcaceae 9.5 8.3 Bifidobacterium 10.3 9.9 9.9 8.9 9.8 9.3 9.3 9.0 Veillonella 6.3 5.9 6.3 2.3 Megasphaera 7.8 7.3 5.3 3.8 5.8 Clostridium-other 9.3 8.6 8.8 a

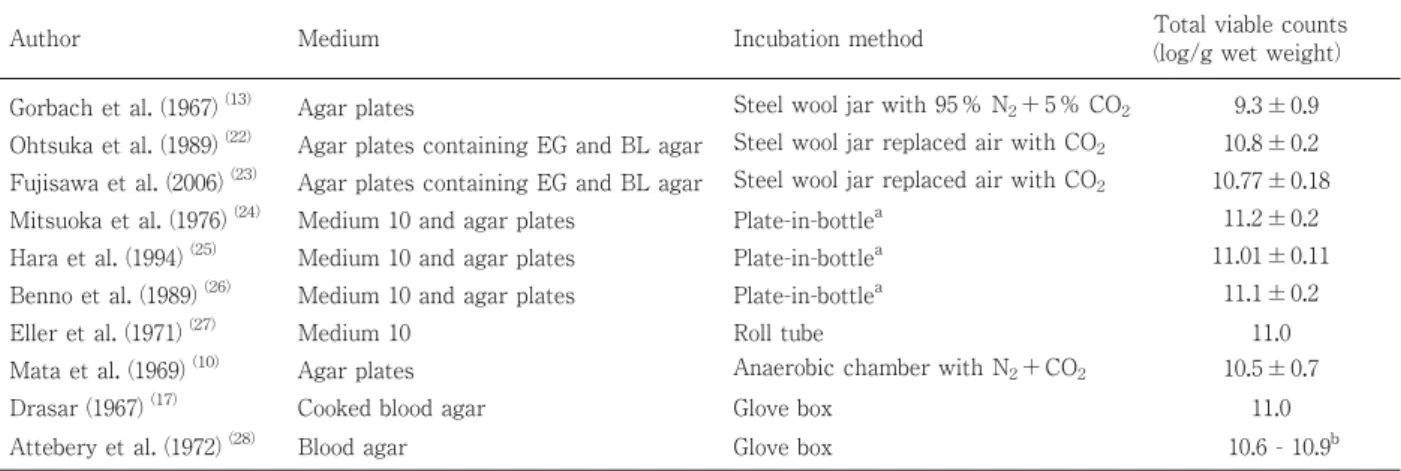

1950 年に Hungate(16)はロールチューブ法を開発し, ルーメンの嫌気性細菌の検索に応用した.この方法はこ れまでのジャー内で寒天培地を嫌気的に培養する手段と はまったく異なる方法であり,操作をすべて嫌気的条件 下で実施するので高度嫌気性菌の分離が可能となった. それ以来,このロールチューブ法の考え方を基礎として 種々の嫌気性菌培養法が考案されてきた.そのひとつが グローブボックス法(17, 18)である.しかし,これら の方法はその操作が煩雑で,多くの検体を処理する上で 困難な問題が多々派生した.ロールチューブ法は寒天の 中に集落をつくらせるので集落の特徴が現れにくく,ま た,釣菌も困難である.一方,グローブボックス法は優 れた嫌気培養法であるが,ゴム手袋による操作やグロー ブボックスの維持管理に手間がかかるなどの欠点があ る.ロールチューブ法やグローブボックス法の詳細につ いては文献(2, 16–20)を参照されたい.ところで, 1969 年,Mitsuoka ら(21)はロールチューブ法を改良 してガラス製のボトルを用いた Plate-in-bottle 法を考案 した.本方法はガラス製の小型のボトルに培地を嫌気的 に分注し,CO2ガス通気下で希釈された検体をやはり CO2ガス通気下でボトル中の培地(Medium 10)に接種 し,嫌気培養する方法であり,コンパクトでありながら 検出される菌数はグローブボックス法のそれと比較して 遜 色 の な い こ と (1 ∼ 2 × 1011/ g)が 示 さ れ て い る (Tables 2, 3).この値は直接検体塗抹による値からする と約 70 %以上の細菌が培養できることになる.ボトル の口が広く,且つ集落を寒天表面に形成させるので釣菌 が容易である.Plate-in-bottle 法を用いた Medium 10 で のみ発育可能な菌株の存在も明らかにされ,本培養法が 高度嫌気性菌の分離に欠かすことの出来ない手段である こと,とりわけ動物の腸内細菌叢の検索には本法の使用 が不可欠であることが示されている(Table 4)(29). 本方法は特別な設備を必要としないので多くの研究施設 で本方法を用いた腸内細菌叢の検索が実施され,ヒトお よびヒト以外の動物種に関しても多くの成果が示されて いる(Tables 5, 6).いずれにしてもローチューブ法, Table 2. Comparison of total bacterial counts by the different methods of investigation for human fecal microbiota.

Author Medium Incubation method Total viable counts

(log/g wet weight) Gorbach et al. (1967) (13) Agar plates Steel wool jar with 95 % N2+ 5 % CO2 9.3 ± 0.9

Ohtsuka et al. (1989) (22) Agar plates containing EG and BL agar Steel wool jar replaced air with CO2 10.8 ± 0.2

Fujisawa et al. (2006) (23) Agar plates containing EG and BL agar Steel wool jar replaced air with CO

2 10.77 ± 0.18

Mitsuoka et al. (1976) (24) Medium 10 and agar plates Plate-in-bottlea 11.2 ± 0.2

Hara et al. (1994) (25) Medium 10 and agar plates Plate-in-bottlea 11.01 ± 0.11

Benno et al. (1989) (26) Medium 10 and agar plates Plate-in-bottlea 11.1 ± 0.2

Eller et al. (1971) (27) Medium 10 Roll tube 11.0

Mata et al. (1969) (10) Agar plates Anaerobic chamber with N2+ CO2 10.5 ± 0.7

Drasar (1967) (17) Cooked blood agar Glove box 11.0

Attebery et al. (1972) (28) Blood agar Glove box 10.6 - 10.9b

aFecal microbiota was analysed by the method of Mitsuoka et al. (24)using both plate-in-bottle method and steel wool jar method. b

Original report is shown as the count log10per gram dry weight.

Table 3. A comparison of colony counts obtained on several media inubated under different anaerobic conditions (29).

Incubation method Medium Human AC-1a Human AC-3a

Direct counts 1.4 × 1011 3.7 × 1011

Steel wool jar BL agar 8.2 × 1010 3.2 × 1010

Steel wool jar EG agar 1.0 × 1011 9.8 × 1010

Plate-in-bottle EG agar 6.1 × 1010 7.5 × 1010

Plate-in-bottle EG (−) agarb 1.4 × 1011 1.4 × 1011 Plate-in-bottle Medium 10

Data are expressed as per gram wet feces.

a

Sample number.

b

EG (−) agar with hemin (5 mg/1000 ml) and menadione (0.5 mg/1000 ml) added and horse blood omitted.

嫌気性グローブボックス法および Plate-in-bottle 法な ど,いわゆる“Prereduced media 法”は嫌気性ジャー を用いる方法と比較して嫌気性菌の培養に優れている. 一方,腸内に存在する細菌の中で,優勢に存在せず,し かも適当な選択培地が示されていない菌群についてはそ の分離において特別の手段を講じる必要がある.検体中 において Clostridium などの芽胞形成菌のみを生残させ る目的で検体を種々の条件で加熱処理を施したり,エタ ノール(40)やクロロフォルム処理(41, 42)を行う手 段も報告されている.このように,嫌気培養法の検討に 加えて検体自体を種々の方法で処理することにより,特 定菌群の検出率を高める試みも同時に行われた. 以下に光岡らが考案した Plate-in-bottle 法を用いる腸 内細菌叢検索時に使用する嫌気性希釈液(B)および Plate-in-bottle 法による Medium 10 の作製方法を示す. 嫌気性希釈液(希釈液 B)の作製法 〔組成〕塩類溶液Ⅰ(0.78 % K2HPO4溶液) 37.5 ml 塩類溶液Ⅱ(0.47 % K2HPO4, 1.18 % NaCl,

1.20%(NH4)2SO4, 0.12 % CaCl2, 0.25 % MgSO4・H2O

を含む溶液) 35.5 ml Resazurin(0.1 %水溶液) 1 ml L-Cysteine・ HCl ・ H2O 0.5 g L-Ascorbic acid(25 %水溶液) 2 ml Na2CO3(8 %溶液) 50 ml Agar 0.5 g 精製水 860 ml 〔調製法〕

L-Cysteine ・ HCl ・ H2O および L-Ascorbic acid 以外 の各成分を加熱溶解し,100 ℃ 15 分くらい加熱したとこ ろで L-Cysteine ・ HCl ・ H2O および L-Ascorbic acid を 加え,直ちに O2を含まない CO2ガスを液内に通気する. Resazurin の 赤 色 が 完 全 に 脱 色 さ れ た ら 加 熱 を や め , 50 ℃くらいにまで冷やしてから試験管に CO2を吹き込 みながら分注してすばやくブチルゴム栓をし,ゴム栓が 飛ばないように押さえをして 115 ℃,20 分間滅菌する. Plate-in-bottle法による Medium 10培地の作製法 〔組成〕 Trypticase 2.0 g Yeast extract 0.5 g Hemin(0.2 % NaOH 水溶液にヘミンを 0.1 %溶解 した溶液) 1 ml VFA混合液 * 3.1 ml Glucose 0.5 g Cellobiose 0.5 g Soluble starch 0.5 g 塩類溶液Ⅰ(希釈液の項参照) 37.5 ml 塩類溶液Ⅱ(希釈液の項参照) 37.5 ml Agar 18 g Resazurin(0.1 %水溶液) 0.5 ml Toray silicone SH5535(10 %水溶液) 5 ml L-Cysteine・ HCl ・ H2O(5 %水溶液) 10 ml L-Ascorbic acid(25 %水溶液) 2 ml Na2CO3(4 %水溶液) 100 ml Table 4. The ability of fastidious anaerobes isolated using plate-in-bottle method to grow on BL and EG

agar plates in stell wool jar (29).

Strain No. of subcultures grown on

Isolated from Bacterial group No. of strains investigated

Steel wool jar Plate-in-bottle

BL agar EG agar Medium 10

Adult human Peptostreptococcus 3 0 1 3

Adult human Bacteroidaceae 2 0 1 (Weak) 2

Adult human Eubacterium 1 0 1 1

Adult human Spirillaceae 3 0 0 3

Pig Bacteroidaceae 3 0 0 3

Pig Curved rods 1 0 0 1

Pig Spirochaetaceae 1 0 0 1 Mouse Bacteroidaceae 3 0 0 3 Mouse Clostridium 1 0 0 1 Mouse Spirillaceae 1 0 0 1 Rabbit Peptostreptococcus 2 0 0 2 Rabbit Bacteroidaceae 2 0 0 2

Auther and anaerobiosis

Mitsuoka et al. (1976)

(24)

Adult person Plate-in-bottle

b

CO

2

Hara et al. (1994)

(25)

Adult person Plate-in-bottle

b

CO

2

Benno et al. (1989)

(26)

Aged person Plate-in-bottle

b

CO

2

Benno et al. (1984)

(30)

Breast-fed infant Steel wool jar

CO

2

Fujisawa et al. (2006)

(23)

Adult person Steel wool jar

CO 2 Total bacteria 11.2 ± 0.2 11.01 ± 0.11 11.1 ± 0.2 10.85 ± 0.59 10.77 ± 0.18 Bacteroidaceae 10.9 ± 0.2 (100) 10.80 ± 0.12 (100) 10.9 ± 0.2 (100) 8.91 ± 1.76 (54) 10.26 ± 0.36 (100) Eubacterium 10.4 ± 0.4 (100) 9.95 ± 0.38 (100) 10.5 ± 0.7 (100) 7.18 ± 1.91 (17) 9.91 ± 0.52 (100) Peptostreptococcus

(Grem positive anaerobic cocci)

10.2 ± 0.3 (100) 9.55 ± 0.26 (100) 10.3 ± 0.4 (100) 5.70 ± 2.40 (6) 9.62 ± 0.24 (100) Bifidobacterium 10.0 ± 0.8 (100) 10.03 ± 0.15 (100) 9.1 ± 0.5 (73) 10.74 ± 0.81 (100) 9.93 ± 0.69 (100) Streptococcus 7.9 ± 1.4 (100) 8.43 ± 0.75 (100) 6.7 ± 1.0 (100) 6.87 ± 1.57 (94) 8.34 ± 0.96 (100) Enterobacteriaceae 7.8 ± 0.8 (100) 8.81 ± 1.22 (100) 8.4 ± 0.8 (100) 8.22 ± 1.12 (97) 8.24 ± 1.42 (100) Lactobacillus 5.8 ± 2.1 (91) 7.68 ± 1.78 (100) 7.2 ± 1.8 (100) 6.25 ± 1.57 (23) 7.15 ± 1.61 (88) Veillonella 7.4 ± 1.2 (79) 6.80 ± 1.21 (50) 5.6 ± 1.8 (80) 6.58 ± 2.19 (43) 6.22 ± 1.34 (75)

Clostridium Lecithinase positive

Clostridium 4.4 ± 1.2 (45) 5.74 ± 1.38 (88) 7.2 ± 1.8 (87) 5.34 ± 1.51 (14) 4.55 ± 1.47 (63) Lecithinase negative Clostridium 9.5 ± 0.5 (67) 9.33 ± 0.35 (100) 9.7 ± 0.6 (100) 7.20 ± 2.98 (46) 8.14 ± 1.29 (50) Spirillaceae 9.7 ± 0.5 (24) Curved rods 9.03 ± 0.49 (50) 9.7 ± 0.1 (13) Megasphaera 9.0 ± 0.5 (33) 9.08 ± 0.67 (88) 9.4 ± 0.6 (13) 9.13 ± 1.22 (9) Stapylococcus 3.1 ± 0.7 (79) 4.70 ± 1.36 (75) 3.8 ± 0.9 (20) 5.43 ± 1.31 (100) 4.11 ± 1.80 (63) Corynebacterium 5.3 ± 2.2 (36) 2.9 (7) 6.70 (3) Bacillus 4.28 ± 1.66 (63) 5.4 ± 1.6 (73) 3.13 ± 0.55 (9) 3.63 ± 1.15 (38) Pseudomonas 3.41 ± 0.85 (63) 3.0 ± 1.1 (20) 3.00 ± 0.57 (11) 4.02 ± 2.72 (38) Yeasts 3.9 ± 1.6 (43) 3.24 ± 0.52 (63) 4.8 ± 1.5 (80) 3.83 ± 1.76 (11) 4.91 ± 0.62 (38)

Auther and anaerobiosis

Kashimura et al. (1989)

(31)

Adult person Steel wool jar

CO

2

Ohtsuka et al. (1989)

(22)

Adult person Steel wool jar

CO 2 Mata et al. (1969) (10) Anaerobic chamber N2 + CO 2 Gorbach et al. (1967) (13)

Steel wool jar

95 % N2 + 5 % CO 2 Draser (1967) (17) Grove box 95 % N2 + 5 % CO 2 Total bacteria 11.0 ± 0.1 10.8 ± 0.2 10.5 ± 0.7 9.3 ± 0.9 Bacteroidaceae 10.8 ± 0.1 (100) 10.6 ± 0.2 (100) 10.3 ± 0.6 (100) 11.0 (100) Eubacterium 9.9 ± 0.4 (100) 9.9 ± 0.3 (100) 9.0 ± 0.9 (67) 11.0 (100) ? Peptostreptococcus

(Grem positive anaerobic cocci)

9.8 ± 0.5 (100) 9.3 ± 0.5 (60) 10.1 ± 0.6 (75) Bifidobacterium 9.7 ± 0.3 (100) 9.7 ± 0.5 (100) 9.4 ± 0.9 (75) 7.2 ± 1.1 (100) Streptococcus 7.5 ± 1.5 (100) 6.7 ± 1.6 (100) 8.7 ± 0.8 (92) 5.7 ± 1.2 (100) 4.0 (100) Enterobacteriaceae 7.2 ± 0.5 (100) 7.2 ± 1.0 (100) 8.7 ± 0.7 (100) 6.4 ± 1.5 (100) 6.4 (100) Lactobacillus 5.5 ± 1.7 (75) 6.3 ± 1.7 (90) 8.6 ± 0.5 (58) 5.3 ± 1.4 (100) 5.5 (100) Veillonella 6.2 ± 1.2 (88) 5.8 ± 2.7 (70) 9.2 ± 0.8 (50) 4.1 (100) Clostridium 9.3 ± 0.9 (58) 3.4 (100) Lecithinase positive Clostridium 4.7 ± 0.4 (50) 5.2 (10) Lecithinase negative Clostridium 7.2 ± 1.3 (38) 9.2 ± 0.6 (90)

Spirillaceae Curved rods Megasphaera

8.8 (13) 7.6 ± 2.6 (20) Stapylococcus 3.3 ± 0.8 (50) 3.5 ± 1.1 (50) 5.0 ± 1.1 (50) 5.2 ± 0.8 (100) Corynebacterium Bacillus 2.6 ± 0.3 (25) Pseudomonas Yeasts 3.4 ± 1.0 (63) 3.6 ± 0.9 (60) 4.0 ± 1.0 (25) 1.8 ± 1.5 (100) 1.4 (100)

aData are expressed as mean

±

SD of log 10 number per gram wet feces. Figures in parentheses are frequency of occurrence (

%

).

b Fecal microbiota was analysed by the method of Mitsuoka et al.

(22)

Authoer and anaerobiosis Benno et al. (1987) (32) Wild Japanese monkey Fujisawa et al. (2010) (33) Calf

Benno & Mitsuoka (1992)

(34) Dog Ito et al. (1984) (35) Cat Fujisawa et al. (1990) (36) Rat Ito et al. (1989) (37) Cotton rat Ito et al. (1983) (38) Mouse IPCR-CV (C57BL/6) Ito et al. (1983) (38) Mouse IMS-CV (BALB/c) Terada et al. (39) (1993) Chick b Total bacteria 10.2 ± 0.3 10.6 ± 0.2 11.0 ± 0.2 10.8 ± 0.2 10.3 ± 0.2 10.3 ± 0.28 10.9 ± 0.2 10.6 ± 0.2 10.3 ± 0.1 Bacteroidaceae 9.5 ± 0.5 (100) 10.2 ± 0.3 (100) 10.8 ± 0.1 (100) 10.3 ± 0.3 (100) 10.0 ± 0.1 (100) 9.6 ± 0.34 (100) 10.7 ± 0.2 (100) 10.4 ± 0.3 (100) 10.1 ± 0.1 (100) Eubacterium 9.3 ± 0.5 (100) 9.8 ± 0.3 (100) 10.2 ± 0.5 (100) 10.1 ± 0.3 (100) 8.8 ± 0.8 (43) 9.0 ± 0.55 (100) 9.1 ± 0.4 (100) 8.5 ± 0.5 (83) 8.6 ± 0.2 (50)

Peptostreptococcus (Gram positive anaerobic cocci)

8.3 ± 0.9 (100) 9.6 ± 0.7 (100) 10.4 ± 0.3 (100) 9.3 ± 0.3 (76) 8.5 ± 0.9 (43) 9.8 ± 0.46 (100) 9.8 ± 0.2 (100) 8.8 ± 0.7 (67) 8.7 ± 0.8 (100) Bifidobacterium 7.5 ± 1.2 (38) 9.3 ± 0.3 (67) 9.7 ± 0.8 (100) 8.5 ± 1.1 (90) 6.4 ± 1.4 (57) 9.7 ± 0.17 (100) 8.4 ± 0.6 (100) 8.0 ± 1.7 (83) 8.9 ± 0.3 (38) Streptococcus 4.1 ± 1.0 (88) 8.8 ± 0.7 (100) 10.0 ± 0.6 (100) 9.3 ± 0.8 (100) 7.3 ± 0.9 (100) 4.6 ± 0.88 (100) 5.8 ± 0.5 (100) 4.7 ± 0.7 (100) 9.1 ± 0.5 (100) Enterobacteriaceae 3.3 ± 0.7 (100) 8.2 ± 0.6 (100) 8.5 ± 0.5 (100) 6.7 ± 1.3 (90) 5.8 ± 0.4 (100) 3.6 ± 0.61 (100) 5.1 ± 0.4 (100) 3.3 ± 0.3 (100) 8.6 ± 0.2 (100) Acinetobacters 5.7 ± 0.4 (100) 5.7 ± 0.4 (100) Proteus 6.3 ± 1.1 (63)

Other gram negative aerobic rods

3.7 ± 0.36 (70) 4.5 ± 1.1 (71) Lactobacillus 8.7 ± 0.7 (100) 8.3 ± 1.0 (100) 9.8 ± 0.5 (100) 9.6 ± 1.0 (100) 9.6 ± 0.3 (100) 9.1 ± 0.4 (100) 9.3 ± 0.3 (100) 9.2 ± 0.5 (100) Veillonella 4.4 ± 1.1 (75) 9.1 ± 0.5 (90) 4.8 ± 0.46 (100) Sarcina ventriculi 7.8 (13) Gemmiger 9.3 ± 0.3 (57) Megasphaera 4.7 ± 0.49 (90) Clostridium 8.3 (10) 9.0 ± 0.5 (86) 9.0 ± 0 (33) Lecithinase positive Clostridium 2.5 ± 0.2 (100) Clostridium perfringens 6.7 ± 0.9 (100) 7.4 ± 1.1 (95) Lecithinase negative Clostridium 10.0 ± 0.3 (38) 9.1 ± 0.7 (100) 9.8 ± 0.3 (100) 9.7 ± 0.4 (100) 7.1 ± 2.1 (71) 8.5 (25)

Coiled form clostridia

7.7 (14)

Spiral shaped rods

8.3 ± 0.5 (38) Spirillaceae 8.4 ± 1.5 (19) Spirochaetaceae 9.7 ± 0.1 (100) 8.3 (10)

Anaerobic curved rods

8.8 ± 0.7 (50) 9.3 ± 0.4 (63) 9.0 (10) 9.2 ± 0.2 (29) 8.7 ± 0.6 (67) Fusiform bacteria 9.2 ± 0.3 (100) 8.7 ± 0.35 (30) 9.7 ± 0.6 (100) 9.9 ± 0.3 (100) Corynebacterium 4.1 ± 1.05 (50) 4.4 ± 1.3 (29) Stapylococcus 3.9 ± 1.0 (67) 3.3 ± 0.6 (50) 3.8 ± 1.0 (100) 3.8 ± 0.3 (14) 3.4 ± 0.46 (70) 3.6 ± 0.6 (57) 5.0 ± 1.5 (67) 4.6 ± 0.6 (100) Bacillus 5.0 (5) 3.7 ± 0.36 (90) 3.0 ± 0 (29) 3.2 ± 0.2 (33) 3.9 ± 0.5 (63) Pseudomonas 4.5 ± 0.5 (83) Yeasts 6.0 ± 0.7 (83) 4.3 ± 0.6 (14) 2.5 ± 0.3 (50)

aData are expressed as mean

±

SD of log 10 number per gram wet feces. Figures in parentheses are frequency of occurrence (

%

).

精製水 850 ml pH 6.7∼ 6.8 *VFA 混合液 Acetic acid 17 ml Propionic acid 6.0 ml n-Butyric acid 4.0 ml iso-Butyric acid 1.0 ml n-Valeric acid 1.0 ml iso-Valeric acid 1.0 ml DL-α-Methyl butyric acid 1.0 ml 〔調製法〕

肉厚ナス型フラスコに L-Cysteine ・ HCl ・ H2O,L-Ascorbic acid,Na2CO3および VFA 混合液以外の成分を 加熱溶解後,加温を続けながら O2を含まない CO2ガス を通気し始め,L-Ascorbic acid 1 ml,添加直前に 2.5 N NaOHで中和した VFA 混合液を加え,Resazurin の赤味 が消えたら空気の混入が無いようすばやくブチルゴム栓 をし,これをしっかりと針金で固定してフラスコに縛り 付ける.115 ℃,20 分間滅菌後,オートクレーブの蒸気 を抜かずに自然に常圧にもどるのを待ってオートクレー ブから取り出し,50 ℃の温浴槽につけ,フラスコ内の 培地の温度が 100 ℃以下となったならば,ゴム栓をはず して CO2ガスを液内に通気し始め,あらかじめ CO2ガ ス を 十 分 に 通 気 し て お い た 滅 菌 Na2CO3溶 液 ,L-Cysteine・ HCl ・ H2O,L-Ascorbic acid(残りの 1 ml) を順次加え,50 ℃くらいになるまで待つ.一方,あら かじめオートクレーブ滅菌しておいた約 2 g のスチール ウール(Grade 0)をピンセットで酸性硫酸銅溶液(1) に浸して赤銅色の還元銅の被膜がついたら引き上げ,滅 菌したペーパータオルで絞り,直ちにボトル(硬質ガラ ス製で,長さ 110 mm,幅 70 mm,深さ 50 mm であり, 首部に直径 33 mm の円形の口が設けられており,この なかにステンレス製のシャーレ(長さ 70 mm,幅 32 mm, 深さ 7 mm)2 枚と小容器(長さ 65 mm,幅 25 mm,深 さ 15 mm)1 個を収め,口部をアルミホイルで覆い,乾 熱滅菌しておく)内のステンレス製の小容器の中に入れ, さらに乾熱滅菌しておいたティッシュペーパー 1 片(40 枚を重ね合わせて 4 cm 角くらいに切ったもの)を入れ る.次いでステンレス製のシャーレ 2 枚に Medium 10 培 地を分注器で CO2ガスをボトル内に吹き込みながら各 15 ml ずつ分注し,ブチルゴム栓(サイズ No. 13)をす る.なお,CO2ガス通気中に培地中の水分が蒸発してし まうので,Na2CO3溶液で水を補うように考慮してある. マウス,ラット,ニワトリなどの腸内細菌叢の検索には, 披試験動物の盲腸内容または糞便の 10 %水抽出液を作 り,この遠心上清を培地に 10 %程度加える必要がある. 寒天が固まったら,37 ℃恒温器に 2 日間くらいボトル の口の部分を少し高くして収め,寒天培地が乾いて周囲 に凝固水が出たら,ティッシュペーパーに吸わせ,完成 である. 培地の検討 腸 内 細 菌 叢 の 研 究 は 1800 年 代 後 期 よ り 開 始 さ れ , 1930 年代にかけて Escherichia coli, Bifidobacterium,

Streptococcus, Lasctobacillus, Bacteroides などの細菌

が分離された.これらの検索に用いられた培地は普通寒 天やブドウ糖寒天培地など限られたものであったので, 嫌気性菌が存在することは示されたが(6, 7),その数 や種類を正確に把握するまでには至らなかった.その後, 腸内に存在する細菌の大部分が偏性嫌気性菌であること から,検出される嫌気性菌の菌数および菌種をいかに増 加させるかを目的として多くの検討がなされてきた.す なわち,菌数の追求はもとより,構成菌種のより正確な 把握の検討である.腸内細菌叢を構成する細菌は菌種, 菌群によってその数は様々であるので,特に少ない菌数 で存在する細菌をいかに検出するかが重要な課題とな る.このためには感度の高い選択培地を複数種類用いる 必要がある.当初の研究における少数の種類の培地によ るデータを見ると,検出される菌種は当然のことながら 少ない.複数の選択培地を用いての腸内細菌叢の検索に 関 し て の 報 告 は 1960 年 代 よ り 見 ら れ る よ う に な り (8–15, 43, 44),Mata ら(10)は BC-1 agar, BC agar お よ び LS agar(Bacteroides, Clostridia, Bifidobacteria, Lactobacilli, Streptococcus, および Veillonellae 分離 培 地 ),L agar(Lactobacillus, Streptococcus 分 離 培 地 ),E agar(Enterococcus 分 離 培 地 ),MS agar (Micrococcus, Stahylococcus, Bacillus 分離培地),T7T agar(Enterobacteriaceae 分 離 培 地 ),SS agar お よ び MacConkey agar(Enterobacteriaceae 分離培地)ならび にLC agar(酵母および糸状菌分離培地)の 10 種類の培 地を用いて,また,Gorbachら(13)はEugon agar(好気 性菌分離培地),Violet-red bile agar(Enterobacteriaseace 分離培地),Mycosel agar(糸状菌分離培地),Urea broth (Proteus 分離培地),Rogosa SL agar, MRS agar および Tomato Juice Special agar( Lactobacillus な ら び に

Bifidobacterium分離培地),SF medium(Streptococcus

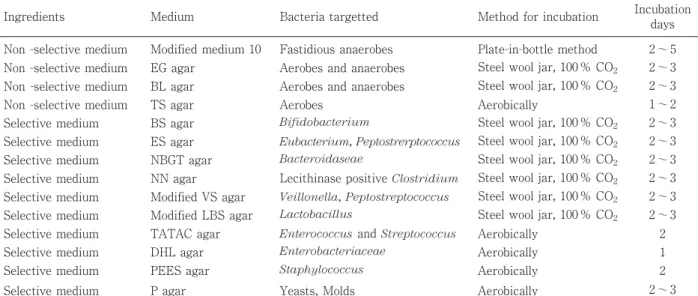

分離培倍地),Staphylococcus medium 110(Micrococcus ならびに Stahylococcus 分離培地),Blood agar(Heart) infusion(嫌気性菌分離培地),および Neomycin-Nagler 培地(Clostridia 分離培地)の 11 種類の培地を用いて検 索を行っている.Mitsuoka ら(15, 24)は

Plate-in-bot-tle 法による Medium 10 培地および 13 種類の非選択なら びに選択寒天平板培地を考案し,これを用いて腸内細菌 叢の検索を実施し,検出される菌数は 1011レベルであり, 10 菌 群 以 上 の 菌 群 が 検 出 可 能 で あ る こ と を 示 し た (Table 7).Mitsuoka らの方法を他の研究者の成果と比 較すると,明らかに細菌の種類および菌数において高い ことが分かる(Table 5).さらに,13 種類の平板培地の 中で,非選択培地である EG および BL 寒天培地は,一 般に用いられる他の非選択培地と比較して発育菌数の多 いことも示されている(Table 8).Plate-in-bottle 法で 使用する Medium 10 培地はヒトや動物の腸内容に類似 した組成を有するものであり,Caldwell & Bryant(45) によってルーメン中の細菌を検索する目的で考案された ものを Mitusoka ら(24)が改良したものである.その 後,Medium 10 培地については更なる検討が加えられ, Ito & Mitsuoka(46)はマウスの腸内細菌叢検索用とし て Medium 10 培地の改良を行っており,盲腸内容抽出 液を培地成分に加えることで検出される菌数が増加する ことを報告している.また,他の動物に関しても同様の 試みがなされ(47, 48),消化管内容抽出物の添加によ っ て 検 出 率 の 向 上 が み ら れ る こ と が 示 さ れ て い る (48). このように,従来のスチールウール法による嫌気性ジ ャー法に上述の Plate-in-bottle 法を加えた包括的な検索 により,高い菌数でしかも検出菌種の多い腸内細菌叢の 検索法が確立された. Plate-in-bottle法を用いた光岡らの方法による糞便細 菌叢の検索法 ビニール袋に検体を採取した後,直ちに袋内を CO2 ガスで満たし,密封した後あるいは CO2ガスを吹き込 みながら均質になるように袋上からよくこね混ぜ,その 一部を秤量して,9 培量の希釈液(B)に加え,101希釈 液を作製する.なお,検体を希釈液に加える際は CO2 ガスを試験管に吹き込みながらゴム栓をすばやくし,気 相を CO2ガスで充満させる.その後,検体と希釈液を 均質にするが,その場合,手で強く振るか嫌気的ホモジ ナイザーで CO2ガスを吹き込みながら実施する.この Table 7. Media and incubation methods for investigation of intestinal microbiota (15, 24).

Ingredients Medium Bacteria targetted Method for incubation Incubation

days

Non -selective medium Modified medium 10 Fastidious anaerobes Plate-in-bottle method 2 ∼ 5

Non -selective medium EG agar Aerobes and anaerobes Steel wool jar, 100 % CO2 2 ∼ 3

Non -selective medium BL agar Aerobes and anaerobes Steel wool jar, 100 % CO2 2 ∼ 3

Non -selective medium TS agar Aerobes Aerobically 1 ∼ 2

Selective medium BS agar Bifidobacterium Steel wool jar, 100 % CO2 2 ∼ 3

Selective medium ES agar Eubacterium, Peptostrerptococcus Steel wool jar, 100 % CO2 2 ∼ 3

Selective medium NBGT agar Bacteroidaseae Steel wool jar, 100 % CO2 2 ∼ 3

Selective medium NN agar Lecithinase positive Clostridium Steel wool jar, 100 % CO2 2 ∼ 3

Selective medium Modified VS agar Veillonella, Peptostreptococcus Steel wool jar, 100 % CO2 2 ∼ 3

Selective medium Modified LBS agar Lactobacillus Steel wool jar, 100 % CO2 2 ∼ 3

Selective medium TATAC agar Enterococcus and Streptococcus Aerobically 2

Selective medium DHL agar Enterobacteriaceae Aerobically 1

Selective medium PEES agar Staphylococcus Aerobically 2

Selective medium P agar Yeasts, Molds Aerobically 2 ∼ 3

Incubation method Medium Human

A 271a

Human A 272a

Steel wool jar BL agar

Steel wool jar EG agar 1.1 × 1011 1.7 × 1011

Steel wool jar Eugon blood agar 6.6 × 1010 7.8 × 1010 Steel wool jar Trypticase soy blood agar

Data are expressed as per gram wet feces.

a

ようにして作製された 101希釈液をもとに順次 10 倍希釈 液を作製し,13 種類(Pseudomonas aeruginosa 分離 用として NAC 寒天培地を加える場合は 14 種類)の各平 板培地の 1/3 ないし 1/4 区画に 0.05 ml を塗抹接種すると ともに Medium 10 培地にも 0.05 ml ずつを接種する.希 釈はすべて CO2ガス通気下で実施するとともに Medium 10に接種の際も CO2ガス通気下で行い,接種後,1 g く らいの滅菌スチールウールを酸性硫酸銅液(1)につけ て滅菌ペーパータオルで絞って入れ,すばやくブチルゴ ム栓をする.各培地の培養条件や検出される菌種,菌群 については Table 7 に示す.なお,スチールウール法に よる平板培地の培養法や培養後の観察法,成績の読み取 り方に関しては文献(1)を参照されたい. 培養法の現状と操作上の問題点 培養法は遺伝子を対象とした腸内細菌叢の解析とは異 なり生菌数を測定するので,採材後,可能な限り迅速に 検査を実施する必要がある.やむを得ずサンプルを輸送 する場合においても迅速に行い,細菌の死滅および増殖 を阻止する工夫が必要である.また,腸内環境に近い状 態,すなわち酸素の混在しない条件下での操作が不可欠 であるので嫌気性菌培養用の器具,設備が必要である. 腸内に存在する細菌の生態や機能を究明するためには細 菌遺伝子のみの検出では不十分であり,やはり生きた細 菌を得る必要がある.培養不可能とされている細菌が存 在する中,分離・培養技術の更なる進捗が望まれる.さ らには一部菌群において新しい分類に即したデータの示 し方も求められる. 一方において,近年は操作の簡易な嫌気培養システム が種々開発されており,Gas Pak システム(日本 BD), Gas Generating システム(Oxoid),アネロパック(三 菱ガス化学)などのガス発生袋を用いる方法が,操作が 簡便なことから,特に臨床検査の分野において臨床材料 からの嫌気性細菌の分離に多用されている.従来のスチ ールウール法と比較して検出状況に遜色が無ければ硫酸 銅の廃液の問題もなくなること,および特別な器具や設 備が不要であることなどから十分使用が可能である.包 括的な比較研究が待たれる. 分子生物学的方法 腸内常在細菌の培養,単離技術の発達により,多くの 腸内細菌が培養され,腸内常在細菌の性状,宿主との関 わりについて明らかにされてきた.しかし,培養法では, 多くの労力と時間が必要なこと,嫌気性菌を培養する為 には特殊な機器,熟練した手技が必要であった.さらに, 消化管内で培養可能な細菌の全体に対する割合は,10 ∼ 50 %(49),20 ∼ 30 %(50)あるいは 20 ∼ 40 %(51) であるともいわれており,未だに培養困難な細菌が存在 する.この数値は,他の環境中の培養可能な細菌は全体 の 1 %にも満たない(52)ことを考えると,決して低い 値ではない.しかし,腸内細菌叢の全体像を理解する為 には,難培養の細菌も含めた解析法が求められていた. 細菌にも rRNA が存在し,rRNA の塩基配列が細菌の 系統解析に用いられた(53, 54).細菌の 16S rRNA 遺伝 子の塩基配列のデータベースが構築され,それを利用し た分子生物学的手法が細菌の分類・同定に有効であるこ とが証明され(55),培養せずに,rRNA の検出により 環境中の微生物叢を解析する方法が取り入れられた (52).分子生物学的手法も用いた微生物叢の解析手法 は,培養法に比べて簡便であり,熟練の技術を必要とせ ず,難培養微生物を含めて解析できるため,多くの研究 者がこぞって導入し,腸内細菌叢の解析にもこの手法が 取り入れられていった.腸内細菌叢の解析では主に, FISH(fluorescence in situ hybridization)法,クロー ンライブラリー法,DGGE 法(denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis)/ TGGE( temperature gradient gel electrophoresis)法 ,T-RFLP(terminal-restriction fragment length polymorphism)法,定量的 PCR(poly-merase chain reaction)法,DNA マイクロアレイ法な どの解析法が用いられており,これら方法の多くが,腸 内細菌がもつ 16S rRNA 遺伝子の塩基配列の多様性に基 づく菌種または菌群の特異的な検出法である.そのため, これら方法に用いられる菌群または菌種特異的プローブ やプライマーが利用されている.分子生物学的手法によ り,ヒト腸内細菌叢では,Clostridium coccoides group,

Clostridium leptum subgroup, Bacteroides fragilis

group,Bifidobacterium,Atopobium cluster といった 菌群が西遊生に検出されると報告されており(51, 56, 57),現在では,多くの研究分野で腸内細菌叢の解析に これら分子生物学的方法が用いられている(Fig. 1).更 に,細菌叢から細菌ゲノムを調製し,16S rRNA 遺伝子 だけでなく,ゲノム全体をシーケンスして細菌叢全体の 遺伝子組成を解析し,その情報に基づき機能特性を解析 するメタゲノム解析法も取り入れられている(58).こ れら分子生物学的解析方法は,この 20 年あまりの間に 様々に発展し,多くの研究者が腸内細菌について研究し やすくなっており,腸内細菌の生態や機能がより詳細に 解析されてきている. FISH法 FISH 法は細胞を破砕し,核酸を抽出することなく, 細胞の形態を維持したままで,蛍光標識されたオリゴヌ

クレオチドプローブとハイブリダイズし,検出する方法 である(59).蛍光顕微鏡下で菌の形態を観察すること ができ,菌の数を得ることもできる.各種腸内細菌に対 する特異的プローブが開発されている.また,高感度の CCD カメラを用い,自動的に菌数を計測するシステム も利用され(60),フローサイトメトリーと組み合わせ た解析も有効な手法である(61, 62).FITC,TAMRA Cy5の 蛍 光 色 素 と プ ロ ー ブ の 組 み 合 わ せ に よ り , Bifidobacterium7 菌種を同時に解析できる multi-color FISH法も報告されている(63).FISH 法は菌体を破砕 することなく検出できるので,腸管内での局在や宿主と の共生関係の解析に有効であると思われる. 理論的には 107個/糞便 1 g の細菌数が無くては,信頼 できる定量結果が得られず,誤差が少ない定量結果を得 る為には 109個/糞便 1 g 以上の細菌数が望ましいとされ ている(59).RRNA 量が少ない菌については検出感度 が低下し,プローブの細胞膜の透過性,ハイブリダイゼ ーションの効率が課題としてあげられる. クローンライブラリー法 糞 便 か ら 細 菌 の DNA を 抽 出 し ,そ れ を 鋳 型 に 16S rRNA遺伝子を PCR で増幅する.増幅産物をクローニン グ し ,各 ク ロ ー ン の 挿 入 さ れ た 塩 基 配 列 を 解 析 し , DNA Data Bank of Japan; DDBJ(http://http://www. ddbj.nig.ac.jp/) や National Center for Biotechnology Information; NCBI(http://http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) の BLAST search,Ribosomal Database Project(http:// http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/)の相同性検索や系統解析を 行い,挿入された配列の菌種を推定する.16S rRNA 遺 伝子の相同性の値(%)と属,種間の関係は分類群によ って異なるが,一般的に相同性 98 %以下であれば同種 であるとされている.そして,クローンの構成比から腸 内細菌叢の構成を推定することができる.この方法は, 培養困難な細菌を含め,未知の細菌についても,遺伝情 報が入手可能であるが,腸内細菌叢の構成を解析するこ とには適しているが,定量性に欠ける.さらに,この方 法を行うには,いくつかの問題点が指摘されている.ま ず,全ての細菌から DNA を均一に抽出することが求め られる.現時点では共通の DNA 抽出方法が無いが,ガ ラスビーズにより細胞を物理的に破砕し,DNA を精製 する方法が多く用いられているようである.そして, PCR で全細菌共通のユニバーサルプライマーを用いる が,プライマーのアニーリング部位の配列の違いから増 幅効率に違いが生じ,増幅されやすい配列と増幅されに Fig. 1. 分子生物学的手法による腸内細菌叢解析

くい配列がある為,解析結果に偏りが生じることがある. 特 に ,27f プ ラ イ マ ー (5’-AGAGTTTGATCMTG-GCTCAG-3’)は Bifidobacterium の 増 幅 効 率 が 悪 い こ とが知られている.PCR では増幅産物が指数関数的に 増えていく為,サイクル数を多くすると,元々サンプル 中に優勢に存在していた配列ほど検出されやすくなり, 偏りが生じることも指摘されている(64).また,サイ クル数が多くなると,本来の塩基配列の一部が他の塩基 配列に置き換わってしまったキメラ配列が生じやすくな る(65).腸内細菌叢の構成を正確に解析する為には, プライマーを PCR の条件が重要になる.クローンライ ブラリー法では,解析するクローンの数により,検出さ れる細菌種の数が決まってくる為,1 検体当たり多くの クローンの解析が必要とされる.この点を克服する為, 近年開発された次世代高速シーケンサーを利用した解析 方法が報告されている(66). DGGE法/TGGE 法

DGGE 法や TGGE 法は DNA の点変異の検出に用いら れていた手法である.二本鎖 DNA を変成条件下で 1 本 鎖 DNA に解離するとき,解離に必要な変性条件が DNA 中の GC 含量によって異なる.DGGE では尿素およびホ ルムアミドの化学変性剤の濃度勾配を持つアクリルアミ ドゲル中で電気泳動をおこない,TGGE では温度勾配を 伴った電気泳動をおこなう(67, 68).実際には,5’側に GC に富む配列を付加したプライマーにより PCR 増幅 し,GC クランプを片側にもつ増幅産物を得る.この増 幅産物を,変性剤濃度勾配があるゲルを用いた電気泳動 あるいは温度勾配のある電気泳動をおこなうと,ある変 性条件下で GC クランプ以外の部分は 2 本鎖が解離し 1 本鎖になるが,GC クランプ部分は解離せず,PCR 産物 はゲル中でハサミのような形となる.1 本鎖 DNA は移 動度が極めて小さい為,解離した PCR 増幅産物は移動 速度が遅くなる.この原理により,糞便から抽出した細 菌 DNA を鋳型にし,PCR 後 DGGE や TGGE により細菌 叢の違いをバンドパターンの違いとして捉えることがで き,得られたバンドパターンを解析ソフトにより解析す ることで,各検体間の類似度を求めることも可能である. さらに,ゲルから目的とするバンドを回収し,そのバン ドの DNA 塩基配列をシークエンスにより決定すれば, クローンライブラリー法と同様に,由来する細菌種を特 定できる.しかし,これら方法では,PCR バイアスの 影響を受ける為,存在する細菌種を全て検出することは 不可能であり,基本的に得られた結果に定量性はない. DGGE/TGGE で検出される細菌は全細菌の 1 %以上を占 める優勢に存在する菌種である(67, 68).また,クロ ーンライブラリーと同様,DNA 抽出のバイアスを受け る場合がある.さらに,異なる細菌種由来でも,移動度 がほぼ等しい場合もある. T-RFLP法 T-RFLP 法では,末端を蛍光標識したプライマーを用 いて PCR をおこない,その増幅産物を制限酵素処理後, DNA シーケンサーによりフラグメント解析し,蛍光標 識された末端 DNA 断片を検出する.そして,各 DNA 断 片の大きさ,蛍光強度により細菌構成を比較する方法で ある.16S rDNA を標的とした解析が多く,この塩基配 列は細菌種により異なり,制限酵素による切断部位も細 菌種によって異なる為,得られる DNA 断片が細菌種固 有であるということに基づいている.また,16S rDNA の情報を利用しやすく,DNA 断片がどの細菌種に由来 するのかを推定できる(69).データの解釈には配列デ ータの充実が必要となり,ヒト腸内フローラの T-RFLP 解析のため,最優勢に存在する 342 菌種の専用データベ ースが構築されている(70).DGGE 法/TGGE 法よりも 操作が簡単ではあるが,異なる細菌種でも同じ長さの DNA 断片を生じることもあり,系統的に近縁な細菌種 間では同じ長さの DNA 断片を生じることが多いので, 使用する制限酵素の種類を増やし,分離能を上げること も必要である.また,定量性に欠け,PCR のバイアス についても考慮する必要がある.T-RLFP では 105cfu/g 以上の細菌種が検出可能であるとされている(69, 71). 定量的 PCR 法 糞便から抽出した細菌の DNA を鋳型にし,標的細菌 の特異プライマー PCR を用いた PCR を行い,増幅産物 をサイクル毎に測定し,基準となる細菌の DNA で作製 した検量線から標的細菌の DNA 量を定量する方法であ る.増幅産物量の測定には SYBR Green などの蛍光色素 や TaqMan probe が用いられている.クローンライブラ リー法,DGGE 法/TGGE 法,T-RFLP 法は細菌叢の細菌 構成の解析に適するものの定量性に欠ける.しかし,定 量的 PCR 法は定量的に細菌叢を評価することが可能で ある.詳細な腸内細菌叢の解析には標的細菌の特異的プ ライマーの充実が重要である.一方,未知の細菌種につ いて評価することはできない.標的とする細菌が 105/糞 便 1 g 以下では特異的な検出ができなくなると考えられ ている(72).rRNA を標的とし,定量的な RT-PCR 法 を用いることで,103/糞便 1 g レベルの菌数でも検出可 能であることが報告されている(73).

DNAマイクロアレイ法 DNA マイクロアレイ法は,16S rRNA 遺伝子データベ ースから,菌種に特異的な配列を見つけ,そこから作製 した特異的プローブを DNA マイクロアレイに固定し, 蛍光ラベルした PCR 産物とハイブリダイズし,細菌種 を検出する方法である(74, 75).これにより一度に多 くの検体を同一条件で解析が可能である. メタゲノム解析 上述の 16S rRNA 遺伝子を標的とした分子生物学的手 法では,細菌叢の構成について解析することが可能であ るが,細菌叢の機能性の解析には直接的な情報を得られ ない.メタゲノム解析は環境下の細菌ゲノムを抽出後, 塩基配列を直接そして網羅的に決定する方法である.得 られた遺伝子情報をバイオインフォマティクスにより解 析し,細菌叢の遺伝子組成とそこから導き出される機能 性を解明することができる(58).様々な環境中の細菌 叢についてメタゲノム解析が行われており,腸内細菌叢 に関しても多く報告されている.例えば,腸内細菌叢で はヒトで欠失している代謝に関わる遺伝子が多く,代謝 機能に関してヒトと腸内細菌叢の間で扶助関係が成り立 っていること(76),宿主の肥満が宿主の遺伝的要因だ けでなく,腸内細菌叢の代謝機能と関係していること (77),乳児では単糖やアミノ酸の取り込みに機能する 遺伝子群が,大人では多糖分解に関与する遺伝子群が多 く,ヒト腸内細菌叢の機能が食事成分に依存すること (78)などが報告されている.また,腸内細菌の多くは 特徴的な遺伝子組成を持ち,消化管に定着し,増殖して いくことに有利な機能を獲得し,腸管腔内の環境に適応 していったことも推察されている(79). この様に,メタゲノム解析により腸内細菌叢を構成す る細菌とそれらの機能性について解析することが可能で ある.次世代シークエンサーの利用により従来のキャピ ラリーシーケンサーよりも効率的にシーケンスが可能と なっており,メタゲノム解析を行いやすくなってきてい る.この解析により得られる情報量が多い為,それを解 析するシステムの充実が必要となる.現在,腸内細菌だ けでなく,ヒト常在菌に関して大規模なメタゲノム解析 をおこなう研究が国際的に進められており,今後,メタ ゲノム解析を用いることで,様々な消化管の疾病と腸内 細菌叢との関係について明らかになることが期待され る. お わ り に 1960 年代に選択培地および非選択培地を用いた培養 法による本格的な腸内細菌叢の検索がなされ始めてから 半世紀が過ぎようとしている.この間,これらの手法を 用いて膨大な研究が積み重ねられ,Bifidobacterium や Lactobacillusといった有用腸内細菌の再認識,プレバ イオティクスやプロバイオティクスといった機能性食品 の開発,腸内細菌叢と年齢,動物種,食事,各種疾病と の関連性など,多くの成果が挙げられ,明らかにされて きた事実も計り知れず,得られた情報が直接現在のわれ われの日常生活に役立てられている.これら腸内細菌叢 検索法の開発は感染症・食中毒原因細菌の検出法の開発 にも匹敵する重要な事柄と考える.一方,近年では分子 生物学的手法を用いる腸内細菌叢の検索が主流になりつ つあり,これまで分からなかった事実が次々に明らかに されてきた.しかしながら,ここで述べた方法にはそれ ぞれ今後に残された検討課題も存在する.今後,一層の 腸内細菌学研究の発展に貢献できる理想的な検索法が, 培養法で得られた知見を基礎として最新の技術を駆使し て確立されることを期待する. 引 用 文 献 (1)光岡知足.1979.腸内常在菌叢.臨床検査23 : 320–334.

(2)Drasar BS, Shiner M, McLeod GM. 1969. Studies of the intestinal flora. I. The bacterial flora of the gastroin-testinal tract in healthy and achlorhydric persons. Gastroenterol 56 : 71–79. (3)光岡知足.1986.腸内菌叢の分類と生態.食生活研究会. 中央公論事業出版.東京. (4)光岡知足編.2006.プロバイオティクス・プレバイオテ ィクス・バイオジェニックス.日本ビフィズス菌センタ ー.アイペック.東京.

(5)van Houte J, Gibbons RJ. 1966. Studies of the cultivable flora of normal human feces. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek

32 : 212–222.

(6)Eggerth AH. 1935. The Gram-positive non-spore-bearing anaerobic bacilli of human feces. J Bacteriol 30 : 277–299.

(7)Eggerth AH, Gagnon BH. 1933. The bacteroides of human feces. J Bacteriol 25 : 389–413.

(8)Smith HW, Crabb WE. 1961. The faecal bacterial flora of animals and man: its development in the young. J Pathol Bacterol 82 : 53–66.

(9)Smith HW, Jones JET. 1963. Observations on the alimen-tary tract and its bacterial flora in healthy and diseased pigs. J Pathol Bacteriol 86 : 387–412.

(10)Mata LJ, Carrillo C, Villatoro E. 1969. Fecal microflora in healthy persons in a preindustrial region. Appl Microbiol

17 : 596–602.

(11)Schaedler RW, Dubos R, Costello R. 1965. The develop-ment of the bacterial flora in the gastrointestinal tract of mice. J Exp Med 122 : 59–66.

(12)Haenel H, Müller-Beuthow W. 1963. Untersuchungen an deutschen und bulgarischen jungen Männern über die intestinale Eubiose. Zbl Bakteriol 1 Orig 188 : 70–80.

(13)Gorbach SL, Nahas L, Lerner PI, Weinstein L. 1967. Studies of intestinal microflora. I. Effects of diet, age, and

periodic sampling on numbers of fecal microorganisms in man. Gastroenterol 53 : 845–855.

(14)Zubrzycki L, Spaulding EH. 1962. Studies on the stabili-ty of the normal human fecal flora. J Bacteriol 83 :

968–974.

(15)Mitsuoka T, Sega T, Yamamoto S. 1965. Eine verbesserte Methodik der qualitativen und quantitativen Analyse der Darmflora von Menschen und Tieren. Zbl Bakt Hyg I Orig

195 : 455–469.

(16)Hungate RE. 1950. The anaerobic mesophilic cellulolytic bacteria. Bacteriol Rev 14 : 1–66.

(17)Drasar BS. 1967. Cultivation of anaerobic intestinal bac-teria. J Patol Bacteriol 94 : 417–427.

(18)Aranki A, Syed SA, Kenney EB, Freter R. 1969. Isolation of anaerobic bacteria from human gingiva and mouse cecum by means of a simplified glove box procedure. Appl Microbiol 17 : 568–576.

(19)Holdman LV, Cato EP, Moore WEC (ed). 1977. Anaerobe Laboratory Manual, 4th ed. Anaerobe Laboratory. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. Blacksburg, Virginia.

(20)上野一恵,光岡知足,渡辺邦友.1982.嫌気性菌の分離 と同定.日本細菌学会教育委員会.菜根出版.東京. (21)Mitsuoka T, Morishita Y, Terada A, Yamamoto S. 1969.

A simple metho (“Plate-in-bottle method”) for the cultiva-tion of fastidious anaerobes. Japan J Microbiol 13 :

383–385.

(22)大塚耕太郎,辨野義己,遠藤希三子,上田弘嗣,小澤修, 内田隆次,光岡知足.1989.4’ガラクトシルラクトース の ヒ ト の 腸 内 フ ロ ー ラ に 及 ぼ す 影 響 .ビ フ ィ ズ ス 2 :

143–149.

(23)Fujisawa T, Shinohara K, Kishimoto Y, Terada A. 2006. Effect of miso soup containing natto on the composition and metabolic activity of the human faecal flora. Microbial Ecol Health Dis 18 : 79–84.

(24)Mitsuoka T, Ohno K, Benno Y, Suzuki K, Namba K. 1976. Die Faekalflora bei Menschen. IV. Mitteilung: Vergleich desneu entwickelten Verfahrens mit dem bisherigen üblichen Verfahren zur Darmfloraanalyse. Zbl Bakt Hyg Abt I Orig A 234 : 219–233.

(25)Hara H, Li ST, Sasaki M, Maruyama T, Tereda A, Ogata Y, Fujita K, Ishigami H, Hara K, Fujimori I, Mitsuoka T. 1994. Effective dose of lactosucrose on fecal flora and fecal metabolites of humans. Bifidobacteria Microflora

13 : 51–63.

(26)Benno Y, Endo K, Mizutani T, Namba Y, Komori T, Mitsuoka T. 1989. Comparison of fecal microflora of elder-ly persons in rural and urban areas of Japan. Appl Environ Microbiol 55 : 1100–1105.

(27)Eller C, Crabill MR, Bryant MP. 1971. Anaerobic roll tube media for nonselective enumeration and isolation of bac-teria in human feces. Appl Microbiol 22 : 522–529.

(28)Attebery HR, Sutter VL, Finegold SM. 1972. Effect of a partially chemically defined diet on normal human fecal flora. Am J Clin Nutr 25 : 1391–1398.

(29)Mitsuoka T, Terada A, Morishita Y. 1973. Die Darmflora von Mensch und Tier. Goldschmidt Informiert Nr. 23 :

23–41.

(30)Benno Y, Sawada K, Mitsuoka T. 1984. The intestinal microflora of infants: Composition of fecal flora in breast-fed and bottle-breast-fed infants. Microbiol Immunol 28 :

975–986.

(31)Kashimura J, Nakajima Y, Benno Y, Endo K, Mitsuoka T. 1989. Effects of palatinose and its condensate intake on human fecal microflora. Bifidobacteria Microflora 8 :

45–50.

(32)Benno Y, Itoh K, Miyao Y, Mitsuoka T. 1987. Comparison of fecal microflora between wild Japanese monkeys in a snowy area and laboratory-related Japanese monkeys. Jpn J Vet Sci 49 : 1059–1064.

(33)Fujisawa T, Sadatoshi A, Ohashi Y, Sakai K, Sera K, Kanbe M. 2010. Influences of Prebio SupportTM(mixture

of fermented products of Lactobacillus gasseri OLL2716 and Propionibacterium freudenreichii ET-3) on the composiotion and metabolic activity of fecal microbiota in calves. Biosci Microflora 29 : 41–45.

(34)Benno Y, Mitsuoka T. 1992. Evaluation of the anaerobic method for the analysis of fecal microflora of beagle dogs. J Vet Med Sci 54 : 1039–1041.

(35)Ito K, Mitsuoka T, Maejima K, Hiraga C, Nakano K. 1984. Comparison of faecal flora of cats based on different hous-ing conditions with special reference to Bifidobactrium. Lab Anim 18 : 280–284.

(36)Fujisawa T, Mizutani T, Iwana H, Ozaki A, Oowada T, Nakamura K, Mitsuoka T. 1990. Effects of culture con-densate of Bifidobacterium longum (MB) on feed effi-ciency, morphology of intestinal epithelial cells, and fecal microflora of rats. Bifidobacteria Microflora 9 : 43–50.

(37)Ito K, Tamura H, Mitsuoka T. 1989. Gastrointestinal flora of cotton rats. Lab Anim 23 : 62–65.

(38)Ito K, Mitsuoka T, Sudo K, Suzuki K. 1983. Comparison of fecal flora of mice based upon different strains and dif-ferent housing conditions. Z. Versuchstierk 25 : 135–146.

(39)Terada A, Hara H, Nakajyo S, Ichikawa H, Hara Y, Fukai K, Kobayashi Y, Mitsuoka T. 1993. Effect of supplements of tea polyphenols on the caecal flora and caecal metabo-lites of chicks. Microbial Ecol Health Dis 6 : 3–9.

(40)Koransky JR, Allen SD, Dowell Jr VR. 1978. Use of ethanol for selective isolation of sporeforming microorganisms. Appl Environ Microbiol 35 : 762–765.

(41)Ito K, Mitsuoka T. 1980. Production of gnotobiotic mice with normal physiological functions. I. Selection of use-ful bacteria from feces of conventional mice. Z Versuchstierk 22 : 173–178.

(42)森下芳行,尾崎明,山本哲三,光岡知足.1980.ノトバ イオートマウスにおけるクロロホルム耐性細菌による盲 腸の縮小並びに大腸菌および腸球菌の発育制御.日細誌

35 : 431–432.

(43)Spears RW, Freter R. 1967. Improved isolation of anaer-obic bacteria from the mouse cecum by maintaining con-tinuous strict anaerobiosis. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 124 :

903–909.

(44)Kalser MH, Cohen R, Arteaga I, Yawn E, Mayoral L, Hoffert WR, Frazier D. 1966. Normal viral and bacterial flora of the human small and large intestine. New England J Med 274 : 500–509.

(45)Caldwell DR, Bryant MP. 1966. Medium without rumen fluid for nonselective enumeration and isolation of rumen bacteria. Appl Microniol 14 : 794–801.

(46)Ito K, Mitsuoka T. 1985. Comparison of media for isola-tion of mouse anaerobic faecal bacteria. Lab Anim 19 :

353–358.

(47)Barnes EM, Impey CS. 1972. Some properties of the non-sporing anaerobes from poulty caeca. J Appl Bacteriol 35 :

241–251.

(48)Salanitro JP, Fairchilds IG, Zgornicki YD. 1974. Isolation, culture characteristics, and identification of anaerobic bacteria from the chicken cecum. Appl Microbiol 27 :

678–687.

(49)Zoetendal EG, Mackie RI. 2005. Moleculer methods in microbial ecology. In Probiotics and prebiotics: scientific aspects, Tannock Gw (ed), p.1-24, Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, UK.

(50)Langendijk PS, Shut F, Jansen GJ, Raangs GC, Kamphus GR, Wilkinson MHK, Welling GW. 1995. Quantitative flu-orescence in situ hybridization of Bifidobacterium with genus-specific 16S rRNA-targeted probes and its appli-cation in fecal samples. Appl Environ Microbiol 61 :

3069–3075.

(51)Suau A, Bonnet R, Sutren M, Godon JJ, Gibson GR, Collins MD, Dore J. 1999. Direct analysis of genes encoding 16S rRNA from complex communities reveals many novel molecular species within the human gut. Appl Environ Microbiol 65 : 4799–4807.

(52)Amman RI, Ludwing W, Schleifer KH. 1995. Phylogenic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol Rev 59 : 143–169.

(53)Woese CR. 1987. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol Rev. 51 :

221–271.

(54)Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. 1990. A definition of domains Archaea, Bacteria , and Eubacteria in terms of small subunit ribosomal characteristics. Syst Appl Microbiol 14 : 305–310.

(55)Olsen GJ, Woese CR, Overbeek R. 1994. The wind of (evo-lutionary) change: Breathing new life into microbiology. J Bacteriol 176 : 1–6.

(56)Harmsen HJ, Raags GC, He T, Degener JE, Welling GW. 2002. Extensive set of 16S rRNA-based probes for detec-tion of bacteria in human feces. Appl Environ Microbiol

68 : 2982–2990.

(57)Matsuki T, Watanabe K, Fujimoto J, Kado Y, Takada T, Matsumoto K, Tanaka R. 2004. Quantitative PCR with 16S rRNA-gene-targeted species-specific primers for analysis of human intestinal bifidobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 70 : 167–173. (58)服部正平,林 哲也,黒川 顕,伊藤武彦,桑原知巳. 2007.ヒト腸内細菌叢のゲノムシーケンス.腸内細菌学 雑誌21 : 187–197. (59)高田敏彦,松本一政,田中隆一郎.2004.腸内フローラ の構造解析:蛍光 in situ ハイブリダイゼーション法.腸 内細菌学雑誌18 : 141–146.

(60)Jansen GJ, Wildeboer-Veloo AC, Tonk RH, Franks AH, Welling GW. 1999. Development and validation of an auto-mated, microscopy-based method for enumeration of

groups of intestinal bacteria. J Microbiol Methods 37 :

215–221.

(61)Zoetendal EG, Ben-Amor K, Harmsen HJM, Schut F, Akkermans ADL, de Vos WM. 2002. Quantification of uncultured Ruminococcus obeum-like bacteria in human fecal samples by fluorescent in situ hybridization and flow cytometry using 16S rRNA-targeted probes. Appl Environ Microbiol 68 : 4225–4232.

(62)Rigottier-Goins L, Rochet V, Garrec N, Suau A, Dore J. 2003. Enumeration of bacteroides species in human fae-ces by fluorescent in situ hybridization combined with flow cytometry using 16S rRNA probes. Syst Appl Microbiol 26 : 110–118.

(63)Takada T, Matsumoto K, Nomoto K. 2004. Development of multi-color FISH method for analysis of seven Bifidobacterium species in human feces. J Microbiol Methods 58 : 413–421.

(64)Bonnet R, Suau A, Dore J, Gibson GR, Collins MD. 2002. Differences in rDNA libraries of faecal bacteria derived from 10- and 25-cycle PCRs. Int J Sys Evol Microbiol 52 :

757–763.

(65)Wang GC, Wang Y. 1997. Frequency of formation of chimeric moleculars as a consequence of PCR coamplifi-cation of 16S rRNA genes from mixed bacteria genomes. Appl Environ Microbiol 63 : 4645–4650.

(66)Nakayama J. 2010. Pyrosequence-based 16S rRNA profil-ing of gastro-intestinal microbiota. Biosci Microflora 29 :

83–96.

(67)Muyzel G, Smalla K. 1998. Application of denaturing gra-dient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) and temperature gradi-ent gel electrophoresis (TGGE) in microbial ecology. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 73 : 127–141.

(68)Muyzel G. 1999. DGGE/TGGE a method for identifying genes from natural ecosystems. Curr Opin Microbiol 2 :

317–322.

(69)Kitts CL. 2001. Terminal restriction fragment patterns: A tool for comparing microbial communities and assessing community dynamics. Curr Issues Intest Microbiol 2 :

17–25.

(70)Matsumoto M, Sakamoto M, Hayashi H, Benno Y. 2005. Novel phylogenic assignment database for terminal-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of human colonic microbiota. J Microbiol Methods 61 :

305–319. (71)坂本光央.2004.腸内フローラの構造解析: T-RFLP 法 を 利 用 し た 腸 内 細 菌 叢 の 解 析 .腸 内 細 菌 学 雑 誌 18 : 155–159. (72)渡辺幸一.2007.腸内フローラの分子生物学的解析法の 応用と課題.腸内細菌学雑誌21 : 199–208.

(73)Matsuda K, Tsuji H, Asahara T, Kado Y, Nomoto K. 2007. Sensitive quantitative detection of commensal bacteria by rRNA-targeted reverse transcription-PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol 73 : 32–39.

(74)Palmer C, Bik EM, DiGiulio DB, Relman DA, Brown PO. 2007. Development of the human infant intestinal micro-biota. PloS Biol 5 : 1556–1573.

(75)Zoentendal EG, Rajilic-Stojanovic M, de Vos WM. High-throuput diversity and functionality analysis of the

gas-trointestinal tract microbiota. Gut 57 : 1605–1615.

(76)Gill SR, Pop M, DeBoy RT, Eckburg PB, Turnbaugh PJ, Samuel BS, Gordon JI, Relman DA, Fraser-Liggett CM, Nelson KE. 2006. Metagenomic analysis of the human dis-tal gut microbiome. Science 312 : 1355–1359.

(77)Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordn JI. 2006. An obesity-associated gut microbio-me with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature

444 : 1027–1031.

(78)Kurokawa K, Itoh T, Kuwahara T, Oshima K, Toh H,

Toyoda A, Takami H, Morita H, Sharma VK, Srivastava TP, Taylor TD, Noguchi H, Mori H, Ogura Y, Ehrlich DS, Itoh K, Takagi T, Sakaki Y, Hayashi T, Hattori M. 2007. Comparative metagenomics revealed commonly enriched gene sets in human gut microbiomes. DNA Res 14 :

169–181.

(79)Hattori M, Taylor TD. 2009. The human intestinal micro-biome: a new frontier of human biology. DNA Res 16 :