Tutorial Note

Exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the

mental health of rehabilitation therapists

Ayahito ITO

1,2*, Toshiyuki ISHIOKA

31. Research Institute for Future Design, Kochi University of Technology 2. Department of Psychology, University of Southampton

3. Department of Occupational Therapy, Saitama Prefectural University Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has a profound impact on our society, and health care professionals are challenged by the present outbreak. A recent study showed that a significant proportion of second-line workers and frontline workers experienced psychological distress. Although these findings suggest the possibility that rehabilitation therapists, especially those who work at the hospital, experience psychological distress, their mental health state has been largely dismissed and the number of an evidence-based practice is limited. Here, we discuss the importance of focusing on the mental health of therapists by introducing studies that focus on the mental health of health care workers during the COVID-19, SARS, and H1N1 influenza pandemics. We then noted the need to track the dynamic relationship between the mental health of therapists and the COVID-19 pandemic by employing longitudinal data collection with psychological measures that reliably and validly capture the mental health of therapists. This approach would be effective for preparation for future pandemics, as we have learned much from previous pandemics. We hope that our Tutorial Note will help readers who are interested in the mental health of rehabilitation therapists and encourage future studies.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-COV-2, mental health, rehabilitation

*Correspondence: Ayahito ITO, OTR, PhD (ayahito.ito@gmail.com), Research Institute for Future Design, Kochi University of Technology,

2-22 Eikokuji-cho, Kochi 780-8515, Japan.

Manuscript history: Received on 12 May 2020; Accepted on 13 May 2020. J-STAGE advance published date: 14 May 2020.

doi: 10.24799/jrehabilneurosci. 200512

Citation: Ito A, Ishioka T. Exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of rehabilitation therapists. J Rehabil Neurosci.

2020; 20(1): 19-23.

1 Introduction

In December 2019, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

(SARS-CoV-2) was identified in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, and immediately spread worldwide[1]. The World Health Organization declared the global COVID-19 outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) on January 30[2]. However, COVID-19 has still been wreaking havoc in human society across continents[2].

As with the pandemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome

(MERS), COVID-19 had a profound negative psychological impact on medical care staff by incurring a heavy burden of intensive care and sustained mental pressure, and the need for prompt action is advocated[3]. Recent literature has revealed that a significant proportion of frontline workers experience psychological symptoms, including depression, anxiety, and insomnia[4]. Surprisingly, nearly 70 % of second-line workers

also experienced psychological distress, and approximately 10 % of second-line workers experience moderate to severe depression and anxiety.

Although this study only focused on physicians and nurses and not on rehabilitation therapists, this finding on second-line workers suggests the possibility that rehabilitation therapists including physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech and language therapists, and psychological therapists are also psychologically affected by the current pandemic. In fact, a recent report from physical therapists warns that psychological problems among therapists should not be underestimated[5]. The World Health Organization, War Trauma Foundation and World Vision International indicated the importance of helper’s own psychological well-being; “Take care of yourself, so you can best take care of others!”[6]. Thus, the rehabilitation therapy community needs to take immediate action to investigate the mental health of therapists during the present pandemic and to provide appropriate support for them, especially those who

are now feeling substantial distress due to worry about being infected or bringing the virus to home or to the workplace. Although the lack of appropriate information regarding therapists might result in inappropriate/inadequate provisions for their rehabilitation, thus far, little scientific evidence of their mental health state has been accumulated. This Tutorial Note briefly overviews the possible mental health care for therapists and provides a possible strategy that may be employed or integrated with research on the mental health of therapists. 2 Possible mental health care for therapists

Deterioration in mental health leads to worsened quality of care

[5,7]. How can we address these problems? Some clues can be drawn from previous literature on past pandemics, such as SARS

(2002-2003) and H1N1 influenza (2009). For example, feeling protected by the hospital (e.g., the provision of protective physical materials such as protection suits, N95 masks and goggles) has been found to be an important factor in workers’

motivation and lower hesitation to work during the H1N1 pandemic[8]. Furthermore, taking precautionary measures and getting clear directives helped professionals during the SARS pandemic[9]. These findings suggest that trust between organizations and workers plays an important role in motivating professionals to work in this confusing situation[10]. It should be noted, however, that 79.7 % of the respondents reported that protection by the hospital was weak during the H1N1 pandemic

[8]. Thus, hospital-based efforts seem to be much more devoted to protecting professionals. In addition, the role of the national association of therapists in each country would also be important because the provision of protective physical materials and information has been found to be critical in supporting workers

[8-10].

As recent evidence suggest a link between psychological symptoms and sleep quality and social support[11], practical advice from frontline workers might help therapists maintain and promote their psychological well-being[12]: “sleep sufficiently and efficiently”, “eat well, at least three times a day”, “maintain contact with your colleagues”, “share decisions with your colleagues”, “constantly update your knowledge”,

“maintain contact with your family and friends”, “make time for your hobbies and daily routine”, and “share your emotions”. Guidance for nursing team members might also help[13]: “while at work, pay attention to your needs for safe working, drinks, food and regular breaks”, “use calming strategies when stress levels are high”. Nevertheless, further scientific evidence should be sought[3].

3 Possible mental health research for therapists The provision of constantly updated information to practitioners, which is deemed to facilitate trust between organizations and workers, requires the gathering and integration of information concerning their work and life situations as well as their mental health. This is now possible by employing a web-based survey in which practitioners answer questions using their own computers or phones when they are available. Of note is that this method enables us to do quick and effortless data collection[14]. In fact, the Japanese Association of Occupational Therapists

officially started an online survey and gathered information about the work and life situations and mental health of occupational therapists from April 27 to May 1, 2020; this survey collected data from 15,292 registered occupational therapists. The results disclosed on May 7, 2020 revealed that more than 80 % of the respondents experienced psychological distress; 7,318 respondents reported a low degree of anxiety and stress and 5,535 respondents reported an intermediate or high degree of anxiety and stress[15]. Although validated psychological measures were not employed and the degree of depression was not measured in this survey, these findings underline the need for prompt psychological support for rehabilitation therapists. We believe that such an approach would be useful to review closely the current situation, not only in Japan but also in other countries currently suffering from the outbreak. In particular, longitudinal data collection will be necessary because it enables us to disentangle the dynamic relationship between the mental health of therapists and the pandemic[16]. This approach is also helpful in assessing the posttraumatic stress symptoms that have been reported during the SARS pandemic[9] and enables us to prepare for second wave[17,18].

Interregional comparison would also be important to delineate the details of the impact of the pandemic because health care workers in the center of the pandemic (e.g., Wuhan, China) showed more severe psychological symptoms than workers outside the center[4]. In Japan, all prefectures are currently under a nationwide state of emergency, which was declared by the government on April 16. Among those prefectures, 13 prefectures were specifically designated

“prefectures with special statements of emergency”, and people in those areas in particular were strongly requested to avoid unnecessary outings. Because such social isolation and loneliness affect mental health[3], special attention should be paid to therapists in such areas, even if they are not on the frontlines.

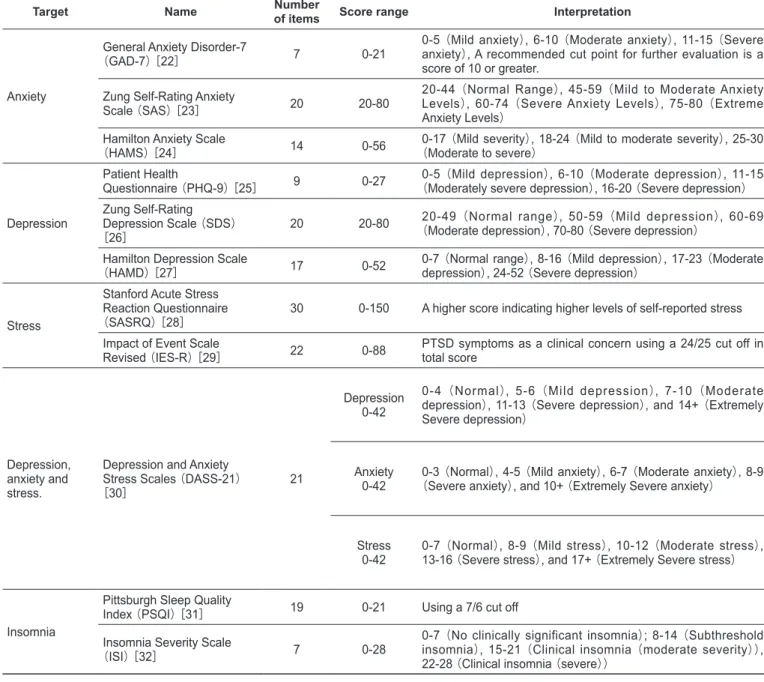

Validated questionnaires help us to reliably and validly measure the mental health of therapists. Table 1 shows the questionnaires employed in recent COVID-19 studies of mental health[19,20]. Specifically, validated measures for depression, anxiety, stress, and insomnia are often employed during this COVID-19 pandemic[4,21]. For example, Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) was designed to screen people with anxiety disorders. The Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) was developed based on factors or patterns of traits found in depressive disorders. Although these questionnaires have been widely used, researchers may replace these questionnaires with other questionnaires, such as the General Anxiety Disorder-7

(GAD-7) and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), to reduce the cognitive load of the respondents.

4 Conclusion

Although there is little evidence about the impact of COVID-19 on the work, life and the mental health of rehabilitation therapists to date, this pandemic has surely been changing our community and society. We will no longer be able to live exactly as we did before, and it is obvious that we will need to protect

ourselves and our families, patients and communities in the midst of such drastic changes.

Obviously, an immediate priority is pursuing ways to support vulnerable groups but we should bear in mind that maintaining the mental health of therapists is essential to provide quality care[5,7]. At an organizational level, the provision of protective physical materials and frequent informational updates seem to be critical in the psychological support of therapists

[8,9]. At a personal level, we can put into practice the advice from other professionals[12,13].

The Japanese Association of Occupational Therapists officially conducted a cross-sectional online survey to provide an evidence-based programs supporting occupational therapists. Although the survey mainly focused on work and life situations, if it combines those types of questionnaires with validated psychological measures and if the data collection is continued

throughout the current pandemic, the obtained data would be helpful in preparations for potential second wave, as such data would capture the dynamic relationship between the mental health of therapists and the pandemic[3,17,18]. Such movements should be spread to other countries, especially those that are seriously affected by COVID-19. We hope that international data sharing and collaboration of the national professional associations will be leveraged for support for therapists in the near future. We believe that if national professional associations continue constant provision of helpful information to therapists through effective data collection, the bonds of trust between the organizations and therapists will be strengthened and lead to better quality of therapy. Note that this approach would be effective not only for the current first wave but also for the second wave and future pandemics, as we have learned much from previous pandemics such as the N1H1

Table 1: Questionnaires widely used for measuring mental health state

Target Name Number of items Score range Interpretation

Anxiety

General Anxiety Disorder-7

(GAD-7) [22] 7 0-21

0-5 (Mild anxiety), 6-10 (Moderate anxiety), 11-15 (Severe anxiety), A recommended cut point for further evaluation is a score of 10 or greater.

Zung Self-Rating Anxiety

Scale (SAS) [23] 20 20-80

20-44 (Normal Range), 45-59 (Mild to Moderate Anxiety Levels), 60-74 (Severe Anxiety Levels), 75-80 (Extreme Anxiety Levels)

Hamilton Anxiety Scale

(HAMS) [24] 14 0-56 (Moderate to severe)0-17 (Mild severity), 18-24 (Mild to moderate severity), 25-30

Depression

Patient Health

Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [25] 9 0-27 (Moderately severe depression), 16-20 (Severe depression)0-5 (Mild depression), 6-10 (Moderate depression), 11-15 Zung Self-Rating

Depression Scale (SDS)

[26] 20 20-80

20-49 (Normal range), 50-59 (Mild depression), 60-69 (Moderate depression), 70-80 (Severe depression)

Hamilton Depression Scale

(HAMD) [27] 17 0-52 0-7 (Normal range), 8-16 (Mild depression), 17-23 (Moderate depression), 24-52 (Severe depression) Stress

Stanford Acute Stress Reaction Questionnaire

(SASRQ) [28] 30 0-150 A higher score indicating higher levels of self-reported stress Impact of Event Scale

Revised (IES-R) [29] 22 0-88 PTSD symptoms as a clinical concern using a 24/25 cut off in total score

Depression, anxiety and stress.

Depression and Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21)

[30] 21

Depression 0-42

0-4 (Normal), 5-6 (Mild depression), 7-10 (Moderate depression), 11-13 (Severe depression), and 14+ (Extremely Severe depression)

Anxiety

0-42 (Severe anxiety), and 10+ (Extremely Severe anxiety)0-3 (Normal), 4-5 (Mild anxiety), 6-7 (Moderate anxiety), 8-9

Stress

0-42 0-7 (Normal), 8-9 (Mild stress), 10-12 (Moderate stress), 13-16 (Severe stress), and 17+ (Extremely Severe stress)

Insomnia

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality

Index (PSQI) [31] 19 0-21 Using a 7/6 cut off Insomnia Severity Scale

(ISI) [32] 7 0-28

0-7 (No clinically significant insomnia); 8-14 (Subthreshold insomnia), 15-21 (Clinical insomnia (moderate severity)), 22-28 (Clinical insomnia (severe))

influenza pandemic[18].

5 Acknowledgments

We thank Marie Levorsen, Ryuta Aoki, Raja R Timilsina, and Shogo Kajimura for valuable comments to earlier version of this manuscript.

6 Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest directly relevant to the content of this article.

References

1. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 [cited 2020 May 6]

2. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/27-04-2020-who-timeline---covid-19 [cited 2020 May 6]

3. Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020; 7(6): p.547-60.

4. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al. Factors Associated With Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020; 3(3): e203976.

5. Pedersini P, Corbellini C, JH. V. Italian Physical Therapists’

Response to the Novel COVID-19 Emergency. Phys Ther. in press.

6. https://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/guide_ field_workers/en/ [cited 2020 May 6].

7. Bassett H, Lloyd C. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health: Managing Stress and Burnout. Br J Occup Ther. 2001; 64(8): 406-11.

8. Imai H, Matsuishi K, Ito A, Mouri K, Kitamura N, Akimoto K, et al. Factors associated with motivation and hesitation to work among health professionals during a public crisis: a cross sectional study of hospital workers in Japan during the pandemic (H1N1) 2009. BMC Public Health. 2010; 10: 672.

9. Sin SS, Huak YC. Psychological impact of the SARS outbreak on a Singaporean rehabilitation department. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2004; 11(9): 417-24.

10. Imai H. Trust is a key factor in the willingness of health professionals to work during the COVID-19 outbreak: Experience from the H1N1 pandemic in Japan 2009. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020; 74(5): 329-30.

11. Xiao H, Zhang Y, Kong D, Li S, Yang N. The Effects of Social Support on Sleep Quality of Medical Staff Treating Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in January and February 2020 in China. Med Sci Monit. 2020; 26: e923549.

12. Alikhani R, Salimi A, Hormati A, Aminnejad R. Mental health advice for frontline healthcare providers caring for patients with COVID-19. Can J Anaesth. 2020; 67(8): 1068-9.

13. https://www.surrey.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-04/ guidance-to-support-nurses-psychological-well-being-during-covid-19-crisis.pdf [cited 2020 May 6]

14. Wright KB. Researching Internet-Based Populations: Advantages and Disadvantages of Online Survey Research, Online Questionnaire Authoring Software Packages, and Web Survey Services. J Comput-Mediat Commun. 2017; 10

(3).

15. http://www.jaot.or.jp/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/report_ ot_covid19_no1_1-7.pdf [cited 2020 May 11]

16. Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, McIntyre RS, et al. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun. 2020; 87: 40-8.

17. Kissler SM, Tedijanto C, Goldstein E, Grad YH, Lipsitch M. Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science. 2020; 368

(6493): 860-8.

18. Shetty P. Preparation for a pandemic: influenza A H1N1. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009; 9(6): 339-40.

19. https://arc-w.nihr.ac.uk/research-and-implementation/covid- 19-response/potential-impact-of-covid-19-on-mental-health-outcomes-and-the-implications-for-service-solutions/

[cited 2020 May 6]

20. Rajkumar RP. COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020; 52: 102066. 21. Kang L, Ma S, Chen M, Yang J, Wang Y, Li R, et al. Impact

on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirusdisease outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun. 2020; 87: 11-7.

22. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006; 166(10): 1092-7.

23. Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971; 12(6): 371-9.

24. Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959; 32(1): 50-5.

25. Manea L, Gilbody S, McMillan D. A diagnostic meta-analysis of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

algorithm scoring method as a screen for depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015; 37(1): 67-75.

26. Zung WW. A Self-Rating Depression Scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965; 12: 63-70.

27. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960; 23: 56-62.

28. Cardeña E, Koopman C, Classen C, Waelde LC, Spiegel D. Psychometric properties of the Stanford Acute Stress Reaction Questionnaire (SASRQ): a valid and reliable measure of acute stress. J Trauma Stress. 2000; 13(4): 719-34.

29. Weiss DS. The Impact of Event Scale-Revised. In: Wilson, JP, Keane TM, editors. Assessing psychological trauma and

PTSD. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2004. p. 168-89.

30. Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. Manual for the Depression Anxiety & Stress Scales. 2nd ed. Sydney: Psychology Foundation of Australia; 1995.

31. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989; 28(2): 193-213.

32. Morin CM, Belleville G, Belanger L, Ivers H. The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011; 34(5): 601-8.

Copyright © 2020 Ayahito ITO, PhD, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License. The use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium are permitted, provided the original author(s) and source are credited in accordance with accepted academic practice.