The Emergence of Depression and Awareness of Illness after the Removal of an Acoustic Neuroma

Chihiro I toi

Akira M idorikawa

Abstract

We report on a patient with an acoustic nerve tumor who underwent an awake craniotomy. The patient was a 56-year-old left-handed man who had a right acoustic nerve tumor and hydrocephalus. Before surgery, the patient expressed no concerns about his condition and exhibited childish behaviors, such as speaking loudly, using exaggerated gestures, and displaying euphoria not appropriate to the preoperative period. During surgery, he suddenly began paying attention to those around him. After surgery, his childish behavior diminished, and he became aware of his hearing loss and impaired orientation. We believe that his peculiar pre-surgery behaviour was due to the pressure exerted on the thalamus, cerebellum, and brainstem by the tumor. Both the direct effect of lesion removal and the indirect effect of increased awareness of his illness may have contributed to the emergence of depression.

Keywords

Awareness of illness, Depression after brain surgery, Acoustic nerve tumor, Awake craniotomy

INTRODUCTION

An acoustic neuroma (AN) is a slow-growing tumor of the eighth cranial nerve, which is typically accompanied by unilateral hearing loss, facial weakness, balance problems, visual problems, and headaches (Ryzenman et al., 2004). Although AN has been reported to have no effect on patientsʼ mental status (Hio et al., 2012), and no differences in depression prevalence was found between a normal population and AN patients (Brooker et al., 2012), depression does appear after surgery in some AN patients (Blomstedt et al., 1996). Previous studies suggested several reasons for depression in AN patients. The first reason is the hearing loss that occurs after AN surgery; AN surgery patients sometimes lose their hearing ability on both the lesion side and the opposite side due to surgery (Hio et al., 2012). It has long been known that hearing loss leads to communication difficulties (Mulrow et al., 1990). People with hearing loss have increased difficulty in understanding speech and often have to ask others to repeat what they said; these difficulties frequently lead to withdrawal from social activities (Arlinger, 2003). Consequently, it is plausible that post-surgery hearing loss might lead to an increased prevalence of depression. Another reason for depression in AN patients is the physical side effects of the surgery: AN surgery may cause several symptoms (Brooker et al., 2012), especially facial weakness (VanSwearingen et al., 1998) and tinnitus (Sullivan et al., 1988; Halford &

Anderson, 1991; Langguth et al., 2011) .

In this brief report, we present an AN patient who showed severe

depression after surgery, despite the absence some of the side effects noted

above. We discuss his depression from a novel perspective compared to

The Emergence of Depression and Awareness of Illness after the Removal of an Acoustic Neuroma

previous articles.

CASE

The patient was a 56-year-old left-handed man with a 12

th-grade education.

He had worked as a salesperson until 10 years prior; after quitting that job, he

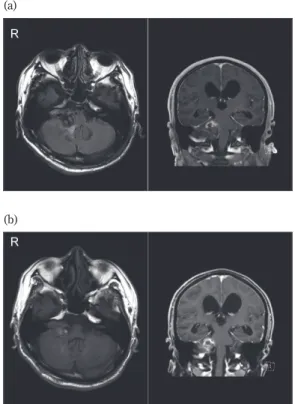

(a)

(b)

Axial MR image and coronal MR image obtained (a) before awake craniotomy and (b) after awake craniotomy. The left image is axial and the right image is coronal.

Figure 1: Magnetic resonance (MR) images

took responsibility for providing care to his father. Although he had noticed hearing loss in his right ear 30 years earlier, he had ignored the symptoms.

His eyesight in both eyes began declining about 6 months earlier, and facial paralysis developed a month before he presented to our institution. Because the patientʼs general practitioner noticed that his right leg was not moving freely, he was referred to the general hospital. Magnetic resonance images revealed a large (4 3cm) right acoustic nerve tumor and hydrocephalus (Figure 1). The AN was pressing on the midbrain, pons, medulla, thalamus and cerebellum. Neurological examinations revealed nystagmus, severe hearing impairment in the left ear, and an inability to stand on one leg. The patient underwent awake craniotomy to remove the AN. After surgery, the patientʼs motor function returned, and he was able to walk normally. His facial ner ve palsy was improved, although the hearing loss persisted.

Comprehensive informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Table 1: Neuropsychological test results before and after surgery Before surgery After surgery

Intelligence (RCPM) 26/36 23/36

Language (SLTA) Naming 19/20 19/20

Repetition 3/5 5/5

Auditory

comprehension 10/10 9/10

Word fluency 12/ min 14/ min

Attention Digit forward score 7 7

Digit backward score 3 3

Praxis Imitating finger

configurations Delayed response Correct response RCPM: Ravenʼs Coloured Progressive Matrices; SLTA: Standard Language Test of Aphasia

The Emergence of Depression and Awareness of Illness after the Removal of an Acoustic Neuroma

Neuropsychological and Neurological Changes

Neuropsychological tests were performed before and after surgery; the results of these tests are summarized in Table 1. Before surgery, the patient showed no awareness of his disease or cognitive decline. After surgery, however, he expressed concern about his cognitive decline and neurological deficits.

Personality Changes

Before the surgery, the patient exhibited childish behavior and impaired insight. He laughed inappropriately and paid no attention to those around him. On finding that he could not move his fingers smoothly due to the disease, he said, “I was a champion at unskillfulness when I was a child”.

However, during awake craniotomy, his insight improved, and he remarked that “I can speak more easily than before the surgery”. Moreover, the patient started to attend to other people. During the surgery, he requested the names of the attending psychologists and asked them about their reasons for choosing that profession. After the surgery, his awareness of his condition was much improved, and he no longer displayed childish behaviors. He also alluded to his cognitive decline, saying, “I got crazy”. The Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) (Zung, 1965) revealed mild depression (46 points) before surgery and severe depression (66 points) after surgery.

One month after surgery, the patient consulted a psychiatrist due to his

depression. Six months after surgery, he visited the general hospital with his

brother, who reported that the patient had become anxious about a month

after surgery and that he was experiencing suicidal ideation. The brother

described the patientʼs personality changes since the onset of the illness. The

patient reported feeling sorry for his family because he had never married and had no regular work. He also felt that he was a different person after surgery, stating that he was previously a cheerful man.

DISCUSSION

In this case report, we present a patient with an AN. Before surgery, the patientʼs tumor was sufficiently large to affect the brainstem, thalamus, and cerebellum. Before removal of the AN, the patient exhibited euphoria, childish behavior, and little awareness of his condition. During surgery, he became aware of his situation and attended to the people around him. After surgery, the patient became severely depressed. Depression after AN surgery is not rare; however, previous reports attributed it to the physical symptoms associated with AN removal (VanSwearingen et al., 1998; Sullivan et al., 1988; Halford & Anderson, 1991; Langguth et al., 2011). After surgery, our patient did not experience any additional physical problems. Therefore, we believe that his depression was due not only to his original physical problem, but also to his increased awareness of his condition.

Before surgery, our patientʼs lesion was sufficiently large to affect the

structures around the acoustic nerve, including the cerebellum, brain stem,

and thalamus. Damage to these areas has been reported to affect personality

and induce emotional problems. For example, Fukatsu et al (1997) reported a

case of childish behavior and euphoria after paramedian thalamic infarcts,

and the cerebral metabolic rate of glucose was markedly decreased in the

thalamus and cerebellum. Thus, the childish behavior of our patient might be

related to the reduced function of the thalamus and cerebellum before

surgery. The brainstem is critical for multimodal integration of sensory

The Emergence of Depression and Awareness of Illness after the Removal of an Acoustic Neuroma

information and the creation of multisensory representations of the self and the body (Fabbro et al., 2015). Before surgery, the patientʼs tumor was sufficiently large to disrupt brainstem functioning, where recovery of this function due to removal of the mass may have improved his insight.

Furthermore, Schmahmann and Sherman (1998) suggested that the cerebellum is critical for cognitive and emotional functioning, where patients with cerebellar lesions show cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome (CCAS), which is characterized by impairment of executive functions, personality changes, and language deficits. A link between cerebellar function and depression has also been reported (Yucel et al., 2013). In the current patient, however, cerebellar function may have been improved due to removal of the tumor, and we do not believe that his depression was due to cerebellar dysfunction. It is possible that the improvements in the neuropsychiatric symptoms were caused by the improvement in hydrocephalus. Indeed, the improved motor function may have been related to hydrocephalus: however, the patientʼs improved awareness of his illness could not be explained by this because his awareness of his illness was improved during the removal of AN.

In summary, we herein presented a case of postoperative depression

following surgery to remove an AN. Before surgery, the patient showed

childish behaviors and a lack of insight into his condition. After surgery, his

childish behavior diminished, and his awareness of his illness improved. We

suggest that the onset of depression after surgery was not a primary

consequence thereof, but rather a secondary effect of improved functioning

of the cerebellum, brainstem, and thalamus. Due to the recovery of

functioning, the patient became aware of the severity of his condition,

including his hearing loss and cognitive decline. Under such circumstances, it

is reasonable to expect that depression might occur.

References

Arlinger, S., “Negative consequences of uncorrected hearing loss-a review”, Int. J.

Audiol, Vol. 42, 2003, 2S17 2S20.

Blomstedt, G.C., Katila, H., Henriksson, M., Ekholm, A., Jääskeläinen, J.E., &

Pyykkö, I., “Depression after surgery for acoustic neuroma”, J. Neurol.

Neurosurg. Psychiatry, Vol. 61, No. 4, 1996, pp. 403 406.

Brooker, J.E., Fletcher, J.M., Dally, M.J., Briggs, R.J.S., Cousins, V.C., Malham, G.M., ... & Burney, S., “Factors associated with anxiety and depression in the management of acoustic neuroma patients”, J. Clin. Neurosci, Vol. 19, No. 2, 2012, pp. 246 251.

Fabbro, F., Aglioti, S.M., Bergamasco, M., Clarici, A., & Panksepp, J., “Evolutionary aspects of self-and world consciousness in vertebrates”, Frontiers in human neuroscience, Vol. 9, 2015, p. 157.

Fukatsu, R., Fujii, T., Yamadori, A., Nagasawa, H., & Sakurai, Y., “Persisting childish behavior after bilateral thalamic infarcts”, Eur. Neurol, Vol. 37, 1997, pp. 230 235.

Halford, J.B., & Anderson, S.D., “Anxiety and depression in tinnitus sufferers”, Journal of psychosomatic research, Vol. 35, No. 4 5, 1991, pp. 383 390.

Hio, S., Kitahara, T., Uno, A., Imai, T., Horii, A., & Inohara, H., “Psychological condition in patients with an acoustic tumor”, Acta Otolaryngol, Vol. 133, No. 1, 2012, pp. 1 5.

Langguth, B., Landgrebe, M., Kleinjung, T., Sand, G.P., & Hajak, G., “Tinnitus and depression”, The world journal of biological psychiatry, Vol. 12, No. 7, 2011, pp. 489 500.

Mulrow, C.D., Aguilar, C., Endicott, J.E., Tuley, M.R., Velez, R., Charlip, W.S., ... &

DeNino, L.A., Quality-of-life changes and hearing impairment: a randomized trial. “Annals of internal medicine”, Vol. 113, No. 3, 1990, pp. 188 194.

Ryzenman, J.M., Pensak, M.L., & Tew, Jr, J.M., Patient perception of comorbid conditions after acoustic neuroma management: survey results from the acoustic neuroma association. The Laryngoscope, Vol. 114, No. 5, 2004, pp. 814 820.

Schmahmann, J.D., & Sherman, J.C., “The cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome”,

The Emergence of Depression and Awareness of Illness after the Removal of an Acoustic Neuroma Brain: a journal of neurology, Vol. 121, No. 4, 1998, pp. 561 579.

Sullivan, M.D., Katon, W., Dobie, R., Sakai, C., Russo, J., & Harrop-Griffiths, J.,

“Disabling tinnitus: association with affective disorder”, General hospital psychiatry, Vol. 10, No. 4, 1988, pp. 285 291.

VanSwearingen, J.M., Cohn, J.F., Turnbull, J., Mrzai, T., & Johnson, P.,

“Psychological distress: linking impairment with disability in facial neuromotor disorders”, Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Vol. 118, No. 6, 1998, pp. 790 796.

Yucel, K., Nazarov, A., Taylor, V.H., Macdonald, K., Hall, G.B., & MacQueen, G.M.,

“Cerebellar vermis volume in major depressive disorder”, Brain Structure and Function, Vol. 218, No. 4, 2013, pp. 851 858.

Zung, W.W., “A self-rating depression scale”, Archives of general psychiatry, Vol. 12, No. 1, 1965, pp. 63 70.