the East‑Asian perspective

著者(英) Simon Humphries

journal or

publication title

Doshisha studies in English

number 91

page range 79‑100

year 2013‑03

権利(英) The Literary Association, Doshisha University URL http://doi.org/10.14988/pa.2017.0000013277

from the East-Asian Perspective

Simon Humphries

Introduction

Since the late 1980s, Japan’s educational policies have aimed to develop the English communicative competence of students with a view to helping the country compete in the global marketplace (Humphries, 2012). In the university sector, selected institutions have become members of the Global 30, which aim to become international hubs (MEXT, n.d.). As a member of the Global 30, Doshisha University is increasing the number of students sent abroad.

Culture is inextricably intertwined with language. Therefore, knowledge of the culture of the people of the target language can help Japanese students to communicate. However, secondary school oral communication textbooks tend to restrict the settings to home and school in Japan (McGroarty &

Taguchi, 2005); therefore, providing low opportunities to learn about target cultures. Understanding the target culture can be difficult, because culture is complex and constantly changing. Information contained in guidebooks can swiftly become out of date and the mass of data on the Internet can overwhelm students. Moreover, the Japanese media tends to focus on extreme and stereotyped examples2. A lack of information about the target culture, or worse misinformed inaccurate knowledge about the target culture can lead to communication breakdown and potentially cause offence.

Cultural difficulties, when they are unexpected, may colour the visitor’s

“entire experience in the [host] country and turn it grey” (Hess, 1997, p. xi).

Therefore, a better source of details is needed to prepare students before they travel overseas.

In the English Department at Doshisha University, I am part of a team that runs a course to prepare students for studying abroad. An element of the course includes inviting students, who have studied at universities overseas, to describe their experiences. During these classes, it became obvious that these guest speakers provided the richest, most relevant source of information for the students in the classes. Japanese people who have been overseas are the best source of information for Japanese who want to go overseas.

Bearing in mind that Japanese people may be surprised by foreign culture due to the reasons described above and through a desire to help bridge the information gap, I decided to ask Japanese who had been to the United Kingdom (UK)3 about aspects that had surprised them during their time overseas. In other words, the findings from this study could guide teachers and textbook-writers to give information relevant to Japanese who want to visit the UK.

Background: England’s changing culture and cultural variety

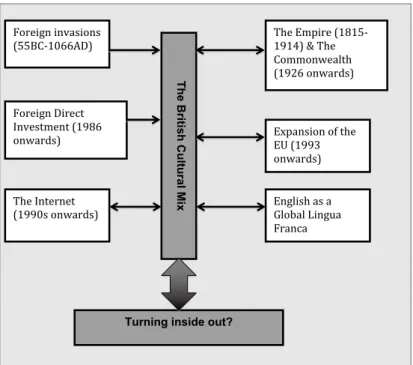

Various factors have combined to ensure that Britain’s culture has kept (and still keeps) changing (Figure 1).

This section describes the factors from Figure 1 to set the context for a multicultural society that has been in a state of flux for over 2000 years. This context underlies the expectation that Japanese visitors will find many surprises.

Invasions: The inward movement of culture

Until 1066, the UK experienced many waves of invasions. Each invading army brought settlers and aspects of their own culture and language. The first major invasion was by the Romans in 55BC who ruled the country for just under 500 years. When the Romans left in 410AD, Germanic settlers

Figure 1. Factors causing the British Cultural Mix

known as Angles, Saxons and Jutes replaced them. From 793AD, Vikings from Scandinavia began raiding the coastal regions and some of them settled. The last major invasion was by William the Conqueror and his army from the Duchy of Normandy in 1066AD. Standard history texts regard 1066 as the last invasion of the English mainland4; however, during the Glorious Revolution of 1688, William of Orange brought a Dutch invasion fleet5.

The Empire: International expansion and sharing

The British Empire developed from 1583 and reached its peak between 1815 and 1914. During this zenith, the British could claim that the sun never set on the Empire that stretched across from Canada in the west, through swathes of Africa, the Middle East, and South and Southeast Asia, as far as Australia, New Zealand and Polynesia in the east. The Empire was gradually replaced from 1926 by the British Commonwealth (now known as the Commonwealth of Nations), which contains independent countries that cooperate within a framework of common goals and values (Commonwealth, n.d.). The existence of the Empire, and later the Commonwealth, facilitated an influx of people who brought their cultures with them.

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI): 1980s onwards

Deregulation in the 1980s meant that the London Stock Exchange became a hub for international finance (Kynaston, 2011). Moreover, many companies also invested in the UK because it was a convenient way to access the European market. The UK has been the main destination for FDI in Europe, which has led to changes in business practices. However,

Germany will probably soon overtake the UK (Gregory & Small, 2012) and foreign investment is now also flowing to Eastern Europe due to the skilled workforce and low salaries.

Expansion of the European Union

Following the signing of the Maastricht Treaty in 1993, a key element of the newly formed European Union (EU) was the internal market. Within the internal market, workers can move freely between the member states when they hold the EU passport. In 2004 and 2007, former Soviet countries from Central and Eastern Europe joined the EU. Many workers have entered the UK from Eastern European countries such as Poland.

The global lingua franca

English is the global lingua franca. This means that it is a medium of communication between people from countries that may not speak English as the first language: for example, for communication between Japanese and Korean people. Many young people realise the economic benefits of learning English in English-speaking countries. According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), America is the top destination for international students (19%). The UK is second, hosting nearly 400,000 international students (11%) (UNESCO, 2012) who add to the cultural mix.

The Internet

The Internet is a powerful force for freely sharing information around the world. English is the lingua franca for sharing ideas over the internet, over half of the world’s websites have content in English (Q-Success, n.d.),

which makes it easier for British people to learn about new cultures6.

Turning inside out?

The UK seems to be turning slowly inside out. The factors described above such as English as a lingua franca mean that, not only is it leading to more people settling in the UK, it is also easier for the British to live, travel and work overseas. A report by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) estimated that 1.1 million British graduates have emigrated, which is second to only Mexico (Winnett, 2008). Some people live overseas and then return, but they bring back new cultural ideas from their lives overseas.

Method

Presenting the research question

All the participants were asked the same research question: “When you went to the UK, in what ways did it differ to your expectations?” To illustrate the before-and-after nature of this question, I used an example from personal experience. During my childhood, excerpts from the Japanese game show ザ・ガマン (Endurance) were shown on popular British TV programmes Clive James on Television and Tarrant on TV. During the Endurance clips, Japanese students suffered from a series of sadistic activities, which included eating a variety of stomach-churning creatures.

Therefore, when I came to Japan and saw タレント (celebrities) devouring extravagant food on nearly every channel anytime in the day, it came as quite a cultural surprise (and disappointment).

Participants

Miles and Huberman (1994) state that samples for qualitative studies should be purposive rather than random. However, participants may also be selected opportunistically based on the researcher’s social network because access and informed consent are easier to obtain (Duff, 2008). This study relied on a diverse and opportunistic sample in order to collect data from a wide variety of viewpoints in a short space of time.

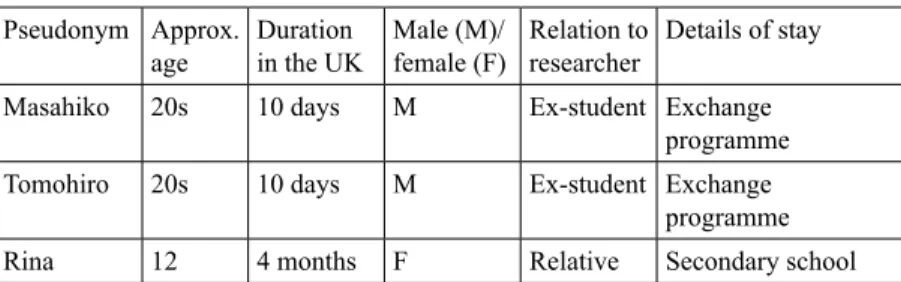

Table 1. Participants Pseudonym Approx.

age Duration

in the UK Male (M)/

female (F) Relation to

researcher Details of stay Masayuki 50s/60s 1 week M Relative Visit family Miyuki 50s/60s 1 week F Relative Visit family Junko 50s/60s 1 year + F None Import business Yoko 30s/40s 1 year + F Colleague Sabbatical Haruka 30s/40s 1 year + F Relative Husband’s job Kaori 30s/40s 1 week F Relative Visit family

Hiro 20s 7 years M Student Primary school

Anna 20s 7 years F Student Primary school

Kana 20s 1 year F Student Exchange

programme

Aki 20s 1 year F Student Exchange

programme

Mika 20s 6 months F Student Home stay

Aiko 20s 2 weeks F Student Family vacation

Xi* 20s 10 days M Ex-student Exchange

programme

Yuto 20s 10 days M Ex-student Exchange

programme

Kenji 20s 10 days M Ex-student Exchange

programme

Pseudonym Approx.

age Duration

in the UK Male (M)/

female (F) Relation to

researcher Details of stay Masahiko 20s 10 days M Ex-student Exchange

programme Tomohiro 20s 10 days M Ex-student Exchange

programme

Rina 12 4 months F Relative Secondary school

*Xi is Chinese

Respondents included seven males and eleven females who were mainly Japanese (Table 1). However, one respondent was a Chinese student who had been living in Japan for four years. The participants’ ages varied from 12 years old to at least one retiree in his 60s (Figure 2). Most of the respondents were in their 20s, because many students and ex-students participated, but I also asked relatives, colleagues and even interviewed a Japanese lady who sat next to me on a flight from London Heathrow.

Figure 2. Summary of Participants’ ages

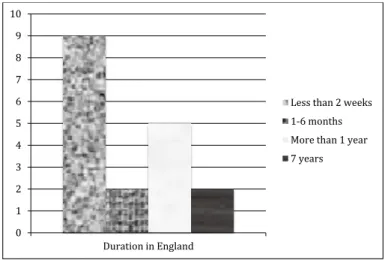

The participants had spent diverse periods of time in the UK, but nine respondents—half the people in the study—had spent two weeks or less in the country (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Summary of Duration in the UK

Data collection and analysis

I collected the data through interviews and email7 and analysed the results using the constant comparison approach to memo-writing (Corbin &

Strauss, 2008). In other words, I used an exploratory qualitative approach based on the research question described earlier and searched for patterns in the data by writing memos (Humphries & Gebhard, 2012). Most of the informants spoke English but I interviewed four people in Japanese.

The Analyst

Despite my attempts to be objective in this study, my background may influence the analysis and data collection. I was raised in England and

moved to Japan after graduating from university. At the time of the study, although I have lived in Japan for a cumulative total of 13 years, I returned to England for an 18-month period after finishing an initial two-year contract in Japan and visited many times for vacations, research and business trips. As a result, I tend not to look back at the UK through nostalgic “rose-tinted spectacles”; rather, I feel that I have a fairly balanced view of the country’s strengths and weaknesses. During the interviews and emails, I tried to stress to the respondents that they should not try to give artificially positive 建て前 responses to avoid offending me. However, it is common that participants may alter their behaviour and responses during a study; therefore, researchers need to be sensitive to these issues (Humphries

& Gebhard, 2012).

Findings

During the study, seven categories arose: food, climate, houses, informal relations, bad service, education and roads (Table 2).

Table 2. Categories Cultural Surprise

Category Data sample

Food British people really eat a lot Climate Lots of rain but no umbrellas Houses The income gap is clear

Informal relations Friends and neighbours removed their shoes Bad service Very slow

Education Studying in Japan makes me cleverer; studying in England makes me grown-up

Roads Roundabouts are a nice idea

These categories are described in the following sections.

Food

The topic that the participants discussed the most was food. They tended to focus on the quality, volume and simplicity.

Many of the participants had heard that English food is widely criticized.

In a poll published at the time of the study, Americans, Australians and Norwegians voted that the United Kingdom had the worst food in the world (Driscoll, 2012). However, the respondents in this study felt surprised that they actually enjoyed English dishes. Xi loved the British breakfast and asked his mother to recreate it when he returned to China, and Kenji enjoyed the “deep taste” of roast lamb that he ate for the first time. Kana qualified that the food was “mostly good” but she ate a dish that she called “yoghurt with rice” that she “couldn’t eat.”8 Kana, Xi and Kenji had all mostly enjoyed food served by their host families, who probably selected dishes that their guests would enjoy. Aki provided a different perspective. She expected the food to be “oily and bad” but found instead that she “ate lots of good food” and explained “I ate at places recommended by locals rather than touristy fast-food places.”

One unexpected problem was the volume of food served and eaten by the English. Xi and Anna both mentioned that the British eat a lot and often.

They both had four meals a day—which were too close together—so they never felt hungry. Masayuki differentiated between the size and use of plates in Japan and the UK. He noted that, although Japanese use many small dishes, the English have one large plate each with more food than he could eat.

Many participants also noticed the simplicity of English food. From one

point of view, this simplicity was a lack of variety. Masayuki commented that he could not find much fish in the supermarket; instead, there were rows and rows of meat. Rina added that her English grandparents ate the same food every week. She claimed that she could almost guess the day of the week based on the food that she ate. Moreover, the food shopping also followed a predictable pattern: “Iceland for pizza and garlic bread; Aldi for bread and vegetables; Morrisons for meat and salads.” From an alternative perspective, food simplicity related to the natural style of the presentation.

Miyuki noted that, in Japan, the food is prepared with the sauces for the consumer; whereas, in the UK, the food has less salt and fewer sauces, and instead, the condiments are supplied on the table separately. She added that she discovered “the real taste of carrots” due to the lack of flavouring.

Haruka had a similar opinion. She appreciated the natural gravy, which is a sauce made from the juices in roasted meat and thickened with flour. Haruka copied this style for cooking after she returned to Japan, but Xi—who had asked his mother to cook British breakfasts in China—found that they could not recreate the dish due to the lack of “brown sauce” for the flavouring.

Climate

The climate is indirectly linked to culture, because it can facilitate or impede the activities that people do. Masayuki, Kaori and Xi all commented on the long summer days. Xi visited the UK in May and said that it was still bright at around 9pm. Masayuki and Kaori both went in July and stated that it was still bright after 10pm. Kaori was surprised to see people sitting outside pubs drinking in beer gardens from the afternoon until the evening.

None of the participants discussed the winter weather, when the days are shorter than during the Japanese winter and the sun sets before 4pm during

late December.

Many participants were shocked by the constant precipitation. Kaori wondered how English people must dry their clothes, because she noticed that they hang them outside in the rain. She also found it amazing that few English people used umbrellas when it rained. Maybe due to the temperate climate, many people use waterproof jackets. Moreover, due to the changeable nature of the weather, many people stand in doorways to wait for rain to pass.

Houses

Miyuki and Xi who both visited rural areas of Cheshire, which is a very flat county in the northwest of England, commented about the wide spaces available for gardens. Xi claimed that it is not possible for Japanese, even those living in rural areas, to have so much space for gardens. Miyuki went further by saying that she was surprised to see so few houses. In between towns, there were wide areas of farmland. Mika had heard about British flower gardens, but she thought that it was a stereotype; therefore, it amazed her to see so many of them.

Haruka noticed that the income gap is very visible due to the types of properties in the UK. She explained that, in Japan, even people on low incomes might have new houses or live in nice apartments. Therefore, she felt that it is difficult to know how much people earn based on their cars and houses in Japan. In contrast, she observed “in England, rich people have big cars and big houses but poor people are very poor. It’s terrible.” Haruka guessed that as English people’s incomes rise, they move into bigger and better places to live. In addition, Yuto said “I was surprised to see that there is still an aristocracy.” However, although he met “an old lady that lived in a

big house,” it is not clear if she had noble lineage.

Informal relations

There are two contrasting stereotypes of British society. From one perspective, there is the enduring image of a stratified society divided along class lines portrayed excellently by nineteenth-century authors in novels such as Great Expectations by Charles Dickens (1996, first published 1860) and Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen (2010, first published 1813). Part of this rigid society is the concept of the British “stiff upper lip”: a stoic attitude encapsulated in poems “If–” by Rudyard Kipling (1995, first published 1910) and “Invictus” by William Ernest Henley (2010, first published 1875). In contrast, there is the more recent perspective of citizens losing control of their emotions, which reached a peak during the riots of the summer of 2011. The participants in this study noticed human traits that indicate a less formal society than they expected.

Many respondents commented on how the English people were friendlier than they expected. Aki said “I have lived in America and England. I thought Americans would be friendlier, but it was different.” She clarified that random people would greet on the buses and trains and start conversations with her. Hiro noted that English people were adaptable. He was impressed and amused because his friends’ families adopted the Japanese custom of removing shoes before entering their own homes.

The principal at the exchange college surprised Yuto, because he did not expect a figure of authority to be so friendly and informal. Yuto illustrated:

“everyone referred to his office as John’s room.” He thought that a principal should be treated differently, but still respected him for it.

The participants also noted that “gentlemen” differed from their

expectations. Haruka observed men’s involvement with their families: “I could see the father pushing the pushchair. In Japan, I can see the mother carrying the baby and the shopping and the man carrying [pause] nothing [laughs].” Tomohiro shared a unique anecdote about his experience of gentlemanly behaviour. In Liverpool, a punk appeared while Tomohiro was struggling to get a pushchair through a doorway. Tomohiro felt scared initially because “for me punk equals violence”; therefore, he was relieved and impressed when the punk helped him.

Haruka and Rina both noticed a lack of stoicism among English people.

Haruka actually felt that Japanese are more stoic than the English: “Japanese don't show their expressions so much … but English people exaggerate their feelings more.” They both commented on the changeable moods of the English. Rina said “if a British person has something good happen to them then they treat other people well.” She described mood changes among girls at school but also noticed visible changes in the behaviour of adults: “if Granddad had a bad day, he got frustrated by other things as well. He was up and down.” Haruka noted that moods seemed to be linked to the weather:

“I had heard about changeable weather but … I didn’t know [that people]

were also changeable according to the weather.” She exemplified: “when cold and wet, people were miserable [pause] not talking [pause] felt more lonely. But when the sky was blue and warm, people were very friendly and kind.”

One area of communication that Haruka found difficult to adjust to was the sarcasm. She noted that there was a high amount of sarcasm among friends: “[I] feel you shouldn’t say that kind of thing to your friend, but realised it’s a normal way of showing closeness.” I explained during the interview that English people might feel that they appear artificial if they are

nice to people whom they are close to and I added that they might be more likely to flatter people when they have a distant relationship. However, when asked subsequently if she preferred flattery or sarcasm from her British husband, Haruka indicated her preference for flattery.

Bad service

Despite the generally positive attitude of the participants toward the informal relationships between British people, there was a general disappointment regarding the standards of service.

Junko noted that British people did not seem to mind slow service. For example, in shops and banks, she claimed that the person at the front of the queue could spend a long time talking with the cashier without seeming to feel any pressure to speed up. Likewise, she observed that the people waiting in the queue seem to be patient. In contrast, she explained that Japanese people will complain and this perceived pressure would cause both the server and the served to finish the transaction quickly. Yoko described a similar incident in a bank. She had spoken to the bank clerk but needed to fill out a form to complete the transaction. While Yoko stood to one side to complete the paperwork, another woman arrived and began counting out coins from a large bag. During this counting process, Yoko tried to return to the bank clerk with her completed paperwork but the customer began shouting at her and claiming that she was jumping the queue. Yoko was surprised, because she believed that she was the original customer. From her experience in Japan, Yoko considered that it was efficient for a bank clerk or postal worker to serve subsequent customers while the first client completed her paperwork. Under such circumstances, the subsequent customer would not complain if the clerk’s attention returned to Yoko—the original

customer. Compared with Junko’s experience in the UK, it would have been culturally appropriate for Yoko to complete the form in front of the bank clerk rather than to the side. The woman holding the bag of coins might have been less likely to complain about waiting than perceived queue jumping.

Regarding the actual service from the cashiers, two different perspectives arose, but both unsettled the participants. Hiro lived in the UK during his primary school years, so he compared the service retrospectively to Japan.

He asserted that the cashiers’ service was “very cold compared to Japan.” In contrast, Masahiko explained that he expected to find bad service because he had heard that the service is poor in the UK in comparison to Japan. In reality, he found that people were “too friendly.” When shopkeepers called him “sweetie” and “love,” he hesitated to choose the appropriate response.

Education

Although many of the participants studied in the UK, only Rina discussed the educational aspects of her experience at an English secondary school.

She said “studying in Japan makes me cleverer; studying in England makes me grown-up.” For example, the British students struggled with mental arithmetic “because they all used calculators.” Rina felt that the students were more mature than in Japan and she attributed it to the style of teaching.

She said “[the teachers] don't help you so much … they stand back and leave it to the students to sort out [finding the answers] by themselves. They don't tell you everything.” As a result, students had the responsibility to ask questions when they did not understand.

Roads

Three participants discussed the different road systems in the UK.

Masayuki and Masahiko described their appreciation for the circular road junctions called roundabouts. Both participants said that roundabouts looked confusing at first but, after they understood the system of giving way and changing lanes, they found that they are very practical for controlling traffic without waiting at red lights. In contrast, the speed of the traffic on the roads made Miyuki nervous. She explained that people drive quickly because the roads are straighter than in Japan. In fact, the speed limits are higher in England than in Japan. On country lanes, cars can drive at 60 miles per hour (96 kilometres per hour), motorways have a speed limit of 70 mph (112 kph), and residential areas have speed limits of 30 mph (48 kph) or 40 mph (64 kph).

Concluding remarks

This was a small-scale study, which explored phenomena that Japanese participants found surprising during visits to the UK. Moreover, as described in the background, the culture of any country is dynamic and the UK, in particular, has experienced various factors leading to a cultural mix and a state of flux where the country is turning inside out. As such, the results of this study should not be generalised, but instead, they provide indicators that teachers and textbook writers may like to consider when preparing students for overseas study.

The biggest surprise arising from this study was the lack of discoveries that broke preconceived expectations. The two exceptions were food and informal relations. The participants had strong images of poor food and a rigid society, but discovered that the cuisine exceeded expectations and

people tended to be warm-hearted (when their moods or the weather suited them). Other surprises arose from the participants’ pre-existing experiences in Japan. Therefore, in comparison to Japan, the participants discussed the climate, housing, service, education and roads. More research is needed to explore which surprises are based on preconceived notions of a country and which surprises have the home country (Japan) as the frame of reference.

Careful searching for differences between Japan and countries such as the UK and improved “understanding of them … will foster improved cross- cultural communication” (Hess, 1997, p. 61). Moreover, more research needs to be done to see how we can break down the stereotypical images of foreign countries arising from collective belief systems embedded and perpetuated by Japan’s language, media, and social norms and roles (Stangor

& Shaller, 1996). It would be interesting to conduct further research using data from Japanese students who visit overseas countries and search for trends in the gaps between their preconceptions and the differences that they discover.

In the future, I would like to make two alterations to the data collection.

Firstly, due to the tight timeframe of this study, an opportunistic sample was collected, which included people of various ages who had stayed in the UK for different periods of time. Therefore, these results cannot be attributed to one group of Japanese. For future studies, it will be better to restrict the sample to Doshisha University students who have participated in the exchange programmes. The results from such a targeted sample would generate useful data for sharing with Doshisha University students preparing to travel overseas. Secondly, despite my efforts to collect some negative images of the UK, the respondents tended to give positive answers. An anonymous reviewer of this paper explained that the hygiene standards,

ethnic diversity, and levels of abuse and public safety surprised his/her students. The participants might have felt reticent to discuss such issues with an Englishman. Therefore, collecting data using interviews by a non-British person or through an anonymous questionnaire could strengthen this study.

* This paper is based on the plenary presentation that I gave to 国際ビジネ スコミュニケーション学会関西支部 (Japan Business Communication Association (JBCA) Kansai Chapter) on 23rd September 2012 at Doshisha University in Kyoto. I would like to thank the JBCA and Chapter President Alex Hayashi for the kind invitation.

Notes

1 This paper uses a general definition of culture from the Oxford Dictionary of English (2010): “the ideas, customs, and social behaviour of a particular people or society”. “Cultural surprises” is a non-technical term, which refers to experiences that did not match prior expectations.

2 For example, in the build up to the FIFA World Cup in Japan and South Korea in 2002, Japanese TV programmes exaggerated two images of England. Firstly, commentators developed hype around the team star David Beckham, so that observers could be forgiven for believing that only one player would represent the England team. Secondly, although England had faced hooligan issues during the 1970s and 1980s, TV programmes frequently replayed old footage. I imagine that local residents were terrified that an army of drunks would come and destroy their properties. On a personal level, as an Englishman and a football fan, my excitement as the tournament drew closer was tempered by people’s ill-informed questions about Beckham and hooliganism ad nauseam.

3 It would be possible to ask people who had visited other countries too but this would make the research too broad. There is also a danger that this research may create new stereotypes about the UK, so I would like to emphasise that the data in

this study represent a small sample of respondents, which should not be generalised.

Rather, I hope that readers will triangulate the information in this study with other sources.

4 Nazi Germany occupied the Channel Islands (Guernsey and Jersey) from 30 June 1940 until liberation 9 May 1945.

5 Despite the use of an invasion fleet, this was also known as “The Bloodless Revolution” as he took the throne without strong opposition. The British parliament invited the Protestant William of Orange to take the English throne because they feared a Catholic alliance between King James II and the powerful French King Louis XIV.

6 The Korean Internet sensation “Gangnam Style” proves an exception to this rule.

It became the first clip to gain over a billion views on the YouTube video search engine (Jones, 2012).

7 The use of email or interview depended on convenience for the respondents.

Participants who could not meet me in person preferred to answer using email.

8 It appears that she was given a dish that originates from India called curd rice.

References

Austen, J. (2010, first published 1813). Pride and Prejudice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Commonwealth. (n.d.). The Commonwealth. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://www.thecommonwealth.org/Internal/191086/191247/the_commonwealth/

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of Qualitative Research (3rd ed.). London:

Sage.

Dickens, C. (1996, first published 1860). Great Expectations. London: Penguin.

Driscoll, B. (2012). UK food is voted the worst by US and Australia in survey. The Huffington Post. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/2012/08/05/uk- food-voted-worst_n_1743282.html

Duff, P. (2008). Case study research in applied linguistics. New York: Routledge.

Gregory, M., & Small, F. (2012). Staying ahead of the game: Ernst & Young’s 2012 attractiveness survey. London: Ernst & Young.

Henley, W. E. (2010, first published 1875). A Book of Verses. Charleston: Nabu Press.

Hess, J. D. (1997). Studying Abroad/ Learning Abroad: An Abridged Edition of the Whole World Guide to Culture Learning. Yarmouth: Intercultural Press Inc.

Humphries, S. (2012). From policy to pedagogy: Exploring the impact of new communicative textbooks on the classroom practice of Japanese teachers of English.

In C. Gitsaki & R. B. Baldauf Jr. (Eds.), Future Directions in Applied Linguistics:

Local and Global Perspectives (pp. 488-507). Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Humphries, S., & Gebhard, J. G. (2012). Observation. In R. Barnard & A. Burns (Eds.), Researching Language Teacher Cognition and Practice (pp. 109-127).

Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Jones, R. C. (2012). Gangnam Style hits one billion views on YouTube. BBC.

Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-20812870

Kipling, R. (1995, first published 1910). Rewards and Fairies. Ware: Wordsworth Editions Limited.

Kynaston, D. (2011). City of London: The History 1815-2000. London: Chatto &

Windus.

McGroarty, M., & Taguchi, N. (2005). Evaluating the communicativeness of EFL textbooks for Japanese secondary schools. In C. Holten & J. Frodesen (Eds.), The Power of Context in Language Teaching and Learning (pp. 211-224). Boston:

Heinle & Heinle.

MEXT. (n.d.). About Global 30. Retrieved December, 31, 2012, from http://www.uni.

international.mext.go.jp/global30/

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, M. A. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Oxford Dictionary of English. (2010). Oxford Dictionary of English. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Q-Success. (n.d.). Usage of Content Languages for Websites. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://w3techs.com/technologies/overview/content_language/all Stangor, C., & Schaller, M. (1996). Stereotypes as individual and collective

representations. In C. N. Macrae, C. Stangor & M. Hewstone (Eds.), Stereotypes and Stereotyping (pp. 3-37). New York: The Guildford Press.

UNESCO. (2012). Global Flow of Tertiary-Level Students. Retrieved December 12, 2012, from http://www.uis.unesco.org/Education/Pages/international-student-flow- viz.aspx

Winnett, R. (2008). Biggest brain drain from UK in 50 years. The Telegraph.

Retrieved from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1579345/Biggest-brain- drain-from-UK-in-50-years.html