Preference of middle-aged Japanese regarding place to receive end-of-life care: a case study of parents of nursing students

全文

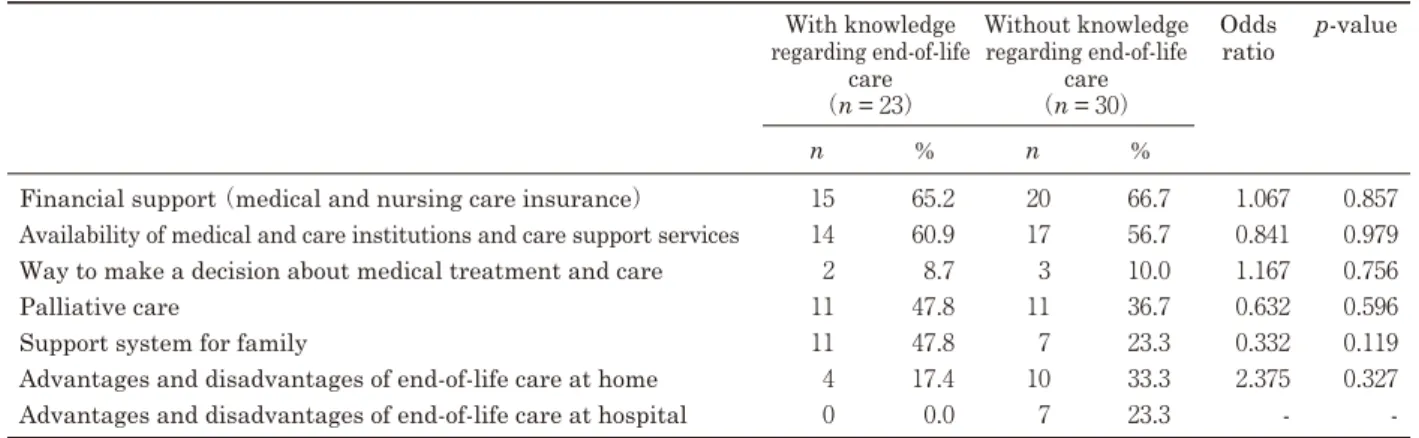

図

関連したドキュメント

Standard domino tableaux have already been considered by many authors [33], [6], [34], [8], [1], but, to the best of our knowledge, the expression of the

Moreover, to obtain the time-decay rate in L q norm of solutions in Theorem 1.1, we first find the Green’s matrix for the linear system using the Fourier transform and then obtain

H ernández , Positive and free boundary solutions to singular nonlinear elliptic problems with absorption; An overview and open problems, in: Proceedings of the Variational

Keywords: Convex order ; Fréchet distribution ; Median ; Mittag-Leffler distribution ; Mittag- Leffler function ; Stable distribution ; Stochastic order.. AMS MSC 2010: Primary 60E05

In Section 3, we show that the clique- width is unbounded in any superfactorial class of graphs, and in Section 4, we prove that the clique-width is bounded in any hereditary

Keywords: continuous time random walk, Brownian motion, collision time, skew Young tableaux, tandem queue.. AMS 2000 Subject Classification: Primary:

Inside this class, we identify a new subclass of Liouvillian integrable systems, under suitable conditions such Liouvillian integrable systems can have at most one limit cycle, and

This paper presents an investigation into the mechanics of this specific problem and develops an analytical approach that accounts for the effects of geometrical and material data on