contemporary Islam in China

著者(英) Junqing Min

journal or

publication title

Journal of the interdisciplinary study of monotheistic religions : JISMOR

volume 8

page range 26‑36

year 2013

権利(英) Doshisha University Center for

Interdisciplinary Study of Monotheistic Religions (CISMOR)

URL http://doi.org/10.14988/re.2017.0000016027

The Present Situation and Characteristics of Contemporary Islam in China

Min Junqing

Abstract

Since it was introduced into China with the arrival of Muslims in the mid-seventh century, Is- lam has developed herein for over 1,300 years and has become one of the five major religions in contemporary China. During the process of the localization of Islam in China, it has divided into many Islamic schools, groups, and sects. In general, such four main groups as Qadim, Ikh- wan, Xidaotang, and Salafiyyah and such four main sects as Khufiyyah, Jahriyyah, Kadiriyah, and Kubrawiyyah have formed in the Chinese mainland; and Ishan, Sunni, and Shiite, etc., have formed in Xinjiang. Although there are some differences in Islamic culture in different areas and in different Muslim nationalities in China, the Islamic belief system has always been strict- ly continued and is still the kernel of Chinese Muslim ethnic culture. Since the 1990s, with the deepening of reform and opening up and the establishment of the commercial trade position of the southeastern coastal areas of China, within the entire country, and even within the whole of Asia, a large number of domestic and foreign Muslims have come to the southeastern coast engaging in commercial activities. Their presence influences and changes Islamic cultural ecol- ogy and social life in eastern Chinese cities. The rich concept of harmony contained in Islam is not only theoretical guidance and a code of conduct for the vast number of Muslims in China, but is also an important ideological resource for both the current Muslim areas and the rest of China toward constructing a harmonious society.

Keywords: China, Islam

Since it entered into China during the Tang and Song dynasties, Islam has developed herein for over 1,300 years and has become one of the five major religions (Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Catholicism, and Protestantism) in contemporary China. Islam was once referred to using different names in Chinese historical records, as “Tajir” during the Tang Dynasty, as the

“Tajik Religion” during the Song Dynasty, as the “Hui Religion” and the “Hui Tajik Religion”

during the Yuan Dynasty, as the “Hui Denomination, Hui Religion, Arabian Religion, Islamic Religion, Mohammedanism” during the Ming Dynasty, and as the “Hui Religion”1) during the

period from the Qing Dynasty to the Republic of China. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the State Council of the People’s Republic of China issued the “Notice of the State Council on the Name of Islam” in July 1956. According to the notice, “Islam is an international religion, and the name of Islam is also an internationally commonly used name, thus this religion should be referred to as Islam instead of as ‘Hui Religion’ in the future.” Since then, Islam has become a uniform name in the Chinese mainland, while the name of “Hui Religion” is still used mainly in Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan.

I. Overview of contemporary Islam in China

1. Population and distribution of Chinese Muslims

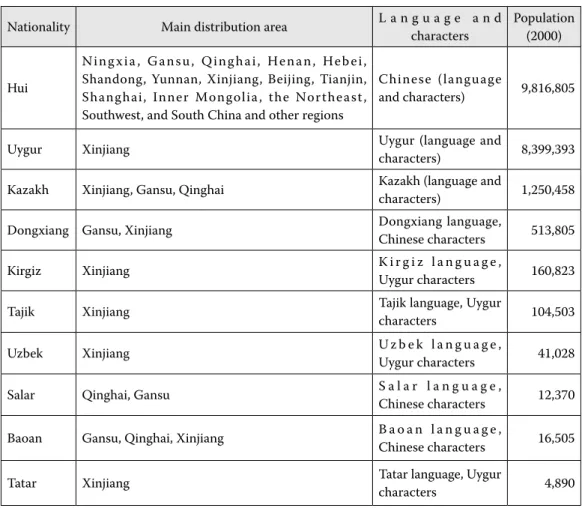

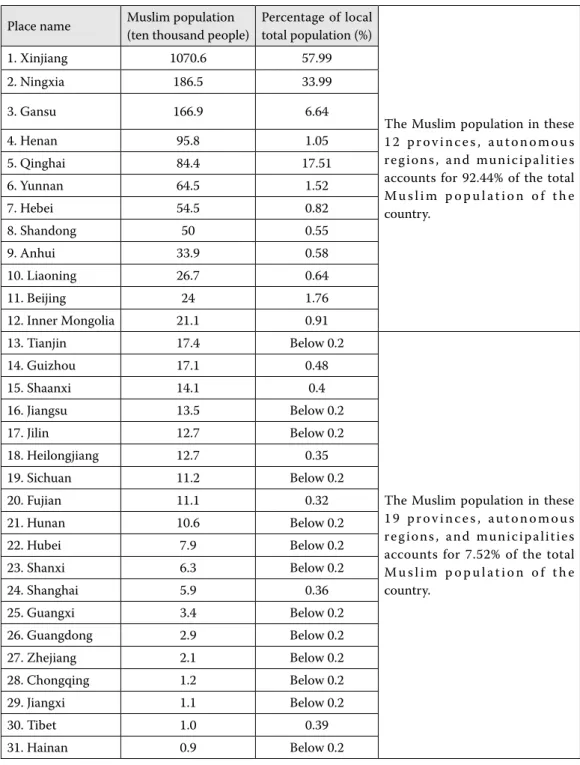

According to the data of the Chinese national census in 2000, the Muslim population of the country is 20,320,580, including such 10 Muslim nationalities as Hui, Uygur, Kazakh, Dongxiang, Kirgiz, Salar, Tajik, Uzbek, Baoan, and Tartar2) (see Table 1). Based on natural population growth, the Muslim population in China is estimated to have reached more than 23 million as of 2010. In the meanwhile, a small number of people of Han, Mongolian, Tibetan, Bai, Dai, and other nationalities believe in Islam. Chinese Muslims are mainly distributed in such provinces and autonomous regions as Xinjiang, Gansu, Ningxia, Henan, Qinghai, Hebei, Shandong, and Yunnan, and a varying number of Muslims are distributed across the country (see Table 2).

Table 1: Table of the distribution area, language & character, and population of Chinese Muslim nationalities

Nationality Main distribution area L a n g u a g e a n d

characters Population (2000)

Hui

Ningxia, Gansu, Qinghai, Henan, Hebei, Shandong, Yunnan, Xinjiang, Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Inner Mongolia, the Northeast, Southwest, and South China and other regions

Chinese (language

and characters) 9,816,805

Uygur Xinjiang Uygur (language and

characters) 8,399,393

Kazakh Xinjiang, Gansu, Qinghai Kazakh (language and

characters) 1,250,458

Dongxiang Gansu, Xinjiang Dongxiang language,

Chinese characters 513,805

Kirgiz Xinjiang K i r g i z l a n g u a g e ,

Uygur characters 160,823

Tajik Xinjiang Tajik language, Uygur

characters 104,503

Uzbek Xinjiang U z b e k l a n g u a g e ,

Uygur characters 41,028

Salar Qinghai, Gansu S a l a r l a n g u a g e ,

Chinese characters 12,370 Baoan Gansu, Qinghai, Xinjiang B a o a n l a n g u a g e ,

Chinese characters 16,505

Tatar Xinjiang Tatar language, Uygur

characters 4,890

Table 2: Muslim populations in various provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities, and their percentage of local total population3)

Place name Muslim population

(ten thousand people) Percentage of local total population (%)

The Muslim population in these 12 prov ince s , autonomous regions, and municipalities accounts for 92.44% of the total Mu s l i m p o p u l at i o n o f th e country.

1. Xinjiang 1070.6 57.99

2. Ningxia 186.5 33.99

3. Gansu 166.9 6.64

4. Henan 95.8 1.05

5. Qinghai 84.4 17.51

6. Yunnan 64.5 1.52

7. Hebei 54.5 0.82

8. Shandong 50 0.55

9. Anhui 33.9 0.58

10. Liaoning 26.7 0.64

11. Beijing 24 1.76

12. Inner Mongolia 21.1 0.91

13. Tianjin 17.4 Below 0.2

The Muslim population in these 19 prov ince s , autonomous regions, and municipalities accounts for 7.52% of the total Mu s l i m p o p u l at i o n o f th e country.

14. Guizhou 17.1 0.48

15. Shaanxi 14.1 0.4

16. Jiangsu 13.5 Below 0.2

17. Jilin 12.7 Below 0.2

18. Heilongjiang 12.7 0.35

19. Sichuan 11.2 Below 0.2

20. Fujian 11.1 0.32

21. Hunan 10.6 Below 0.2

22. Hubei 7.9 Below 0.2

23. Shanxi 6.3 Below 0.2

24. Shanghai 5.9 0.36

25. Guangxi 3.4 Below 0.2

26. Guangdong 2.9 Below 0.2

27. Zhejiang 2.1 Below 0.2

28. Chongqing 1.2 Below 0.2

29. Jiangxi 1.1 Below 0.2

30. Tibet 1.0 0.39

31. Hainan 0.9 Below 0.2

As seen from Table 1 and Table 2, from regional and cultural-type perspectives, Chinese Muslims can be divided, in a broad sense, into Hui-based inland Muslims and Uygur-based Xinjiang Muslims, and the population distribution still maintains, as a whole, the pattern of

“overall dispersion with local concentration,” in a conventional sense. However, it is important to note that the fact that Muslims are spread out across almost all counties and cities in China reflects its socio-cultural diversity and complexity.

2. Islamic groups and mosques 1) Islamic groups

The national Islamic religious group, China Islamic Association, was founded by Chinese Muslims in Beijing in May 1953, and since then, 29 Islamic associations at the provincial and municipality level, 186 Islamic associations at the prefectural level, and 291 Islamic associations at the county level has been founded in succession.4) The main tasks of these Islamic groups are to: carry out Islam activities; organize Islamic education to cultivate Islam faculty and staff;

explore and systemize the historical and cultural heritage of Islam, carry out Islamic academic cultural studies, and compile and publish classic works, books, and periodicals; organize ethnic Muslims across the country to make the Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca; and engage in friendly exchanges with Muslims and the Islamic organizations of various countries on behalf of Chinese Muslims.

2) Mosques

The mosque buildings in China, depending on their creation time and distribution region, can be divided into three styles: 1. Arabian-type mosque building during the Tang, Song, and Yuan dynasties, such as the Huaisheng Mosque in Guangzhou, Qingjing Mosque in Quanzhou, Fenghuang Mosque in Hangzhou, Xianhe Mosque in Yangzhou, and other ancient Chinese mosques built in the Tang and Song dynasties; 2. The mosque building of Chinese hall style in Hui areas since the Ming and Qing dynasties; the mosques during the Ming and Qing dynasties, especially inland mosques, were increasingly influenced by classical Chinese architecture, resulting in a large change in architectural content; the preaching hall and bathroom, etc., were added to the overall structure in addition to the worship hall and minaret; and 3. The mosque building of Western Asia and Central Asia style in the Xinjiang region. Its architectural form maintains more Arabian Islamic characteristics, using timber, adobe, brick, and glazed brick to build a dome or flat-top building, and combining open halls with closed halls. At present, the newly built mosques by the Hui people in the Gansu, Ningxia, and Qinghai regions in northwest China mostly adopt Arabian dome architectural style. In addition, the mosque buildings in different places also absorb the local ethnic architecture artistic elements, such as Lhasa Grand Mosque, in which the overall building structure and detailed decoration adopt color painting, and in which the stone masonry, color, lines, and patterns outside the main hall

and minaret use a means of artistic expression from local Tibetan architecture; meanwhile, the Hui mosque buildings in the Xishuangbanna region in Yunnan are in the form of a Dai bamboo house.

At present, there are more than 34,000 mosques in the country, among which, there are more than 24,000 mosques in Xinjiang, and this means approximately one mosque for every 400 Muslims. There is at least one mosque in each natural village in southern Xinjjiang, with basically a Jumah mosque in each incorporated village.5)

3. Islamic sects

As Islam developed and widely spread around the world, a number of groups, representing different social thoughts, doctrines, and political interests, emerged in the form of religious sects around the world. During the localization process of Islam in China, Islam there was also divided into many religious denominations and branches. During the late Ming and early Qing periods, Islamic Sufism spread in inland China through Xinjiang, Ishan formed in Xinjiang, and the sect system gradually formed combining the ecclesiastical hierarchy of inland Sufism with a feudal patriarchal clan system in the northwestern Muslim regions. The sect is not only an organizational form of religious denomination, but also consists of influential and privileged families of the upper religious class. As many as 30 to 40 sects, large or small, have appeared. In the meanwhile, the Xidaotang sect was generated in China itself, which advocates developing Islamic principles by resorting to Chinese culture. Thus, on the whole, such four main denominations as Qadim, Ikhwan, Xidaotang, and Salafiyyah and such four main sects as Khufiyyah, Jahriyyah, Kadiriyah, and Kubrawiyyah have formed in the Chinese mainland; and Ishan, Sunni, and Shiite, etc., have formed in Xinjiang.

II. General characteristics of contemporary Islam in China

1. The Islamic faith is the cultural kernel of Muslim nationalities.

With the formation of localized Islamic thoughts, Islam has been closely correlated with specific nationalities, and this correlation in general exhibits two properties: During the process of the localization of Islam in the inland area, the Islamic culture and Sinic culture fused with each other, directly forming such four new national communities as Hui, Dongxiang, Salar, and Baoan; and in Xinjiang, during the long process of Islamic cultural fusion with and the absorption of Turkic culture, Uygur, Kazakh, Uzbek, Kirgiz, Tatar, and Tajik were gradually Islamized. The localization of Islam in China is the process of mutual acceptance, absorption, and integration between Islamic culture and different cultures, and is deeply intertwined with

For all four inland Muslim nationalities, the Islamic faith is the decisive cultural internal force in nationality formation and development. For this reason, Dongxiang, Salar, and Baoan were historically referred to as “Dongxiang Hui,” “Salar Hui,” and “Baoan Hui,” respectively, and the national members generally accept these names as well. For the inland Muslim nationalities generated and based on Islamic faith as the core connection point, Islamic faith and culture is the foundation of the group identity to which they are attached.

We can say that, without Islamic transplantation in Chinese society, at least such Muslim nationalities as Hui, Dongxiang, Salar, and Baoan would not have formed, and the formation of such four Muslim nationalities is the localization result of Islam in a specific regional and cultural environment in Chinese society. Although, Dongxiang, Salar, and Baoan have their own special formation process and have their own national languages, the Islamic culture of these three nationalities is profoundly influenced by Sinic culture, and Chinese language and Chinese characters are widely used among their national members. At the same time, Islamic faith and culture are the “assumed givens” and the “intrinsic motivation” for these groups to form a national community within particular historical scenarios, and they are the spiritual origin of boundary construction and the root of the group identity of Muslim nationalities regarding interaction with other communities.

With the start of Islamization in the Xinjiang region, Islam in this region shows significant ethnic characteristics and regional characteristics. Although all six Muslim nationalities in Xinjiang fall under Turkic people, as its culture creates a system of its own, the process of Islamization has different characteristics, i.e., Islam in Xinjiang is still characterized by diversity in the process of localization and nationalization. Before Islamization, the ancient Uygur, Kazakh, and Kirgiz believed in Shamanism and other religions. Therefore, the process of Islamization is the collision and integration process of Islam and other religions such as Shamanism. This collision and integration reflect local and national characteristics of religions in Xinjiang, and are the root cause of the long-term popularity and development of foreign religions, including Islam.

Both the two major Islamic cultural systems in the inland and in Xinjiang, and the specific Islamic cultural characteristics of each Muslim nationality, reflect the inevitable localization process and diversified form of Islam in the spreading-out process. However, it should be stressed that, in the localization process, Islam only changes its expression means suitable for the local cultural characteristics instead of changing its own belief system. Thus, despite the fact that Chinese Islamic cultures somewhat vary in different regions and in different Muslim nationalities, however, the Islamic belief system has always been strictly continued and is still the kernel of Chinese Muslim ethnic cultures.

2. Floating Muslims influence and change Islamic cultural ecology and social life in east- ern Chinese cities

Since the 1990s, with the deepening of reform and opening up and the establishment of the commercial trade position of the southeastern coastal areas of China, within the entire country, and even within the whole of Asia, a large number of domestic and foreign Muslims have come to the southeastern coast engaging in commercial activities. Their arrival not only revitalizes commerce and trade in the region, but also inputs fresh blood for the revival of local Islamic culture.

With domestic and foreign Muslim groups following footsteps in the southeastern coastal areas, the local dusty mosque doors are opened, the melodious wonderful Adhan are chanted, and worshipping five times a day is started, bringing back the former connections and warmth of the mosque. On every Friday prayer or Eid al-Adha or Eid al-Fitr, the mosque is overcrowded. In August 2011, the author learned in the investigation that 400 to 7,000 people worshipped on Friday prayers at all open mosques in southeastern coastal areas, and on the prayers of Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha, more than 20,000 people worshipped in the Sages Tomb Mosque in Guangzhou and Yiwu Mosque, etc., with more than 2,000 people worshipping in most mosques.

As indicated by the Annual Report on Religions in China (2009) issued by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, as of 2008, China has about 3 million floating Muslims,6) with a large increase over floating Muslims statistics in 2005 (2 million).

It is known that the original number of permanent Muslim residents in Jiangsu Province was 170,000 (in 2000). In recent years, it has increased at a rate of 20,000 people per year. In 2009, more than 53,000 non-local Muslims received temporary residence permits in Nanjing alone. The original Muslim population in Shanghai was about 60,000 and has now reached 160,000. The number of local Muslims in Fujian Province is just over 3,000, but there are over 15,000 non-local Muslims as well, mainly scattering in Fuzhou, Quanzhou, Xiamen, and Nanping, etc. Of the floating Muslim population in China, Hui people account for 89.8%, Uygur people account for 4.8%, and Salar, Dongxiang, and Baoan people account for 3.9%—mostly coming from Northwest China. The floating Muslims coming from Gansu, Qinghai, Xinjiang, and Ningxia account for 81.3% of the entire floating Muslim population.7)

In August 2010, when the author went to mosques in Fuzhou City, Quanzhou City, and Xiamen City in Fujian Province; Hangzhou City and Yiwu City in Zhejiang Province; Shanghai

worship at any time. They cheerfully came to the mosque to worship and then disappeared into the urban crowd. Although Muslim population varies greatly in different regions, diversity is still the basic tone of Islamic cultural ecology in southeastern coastal areas. It can be said that, the emergence of a floating Muslim population influences and changes Islamic cultural ecology and social life in eastern Chinese cities.

3. Islam contributes a positive spiritual resource to the social harmony of contemporary China

In the current wave of globalization, humans need to dig down into their own individual cultural traditions for ideological resources with modern value and inherent potentials, in order to adapt to social development, and must interpret such to the benefit of human development and social harmony. This is done to provide positive and healthy spiritual power and psychological support for the modernization of various nationalities.

Since it was introduced into China in the mid-seventh century, Islam, in its long course of historical development, has been accepted and absorbed by Chinese culture and has become an integral part of it, and Islamic culture constantly adapts and innovates itself to China’s social structure. The contained rich concept of harmony is not only theoretical guidance and a code of conduct for the vast number of Muslims in China, but is also an important ideological resource for both the current Muslim areas and the rest of China toward constructing a harmonious society.

The harmony concept of Islamic culture has a strong holistic view, covering all levels of Heaven, Earth, and people, with reverence for Allah going hand-in-hand with love for people, spirit going side by side with substance, and man living in harmony with himself, with others, with nature, and with society. Islamic culture aims at building a harmonious society and harmonious world, advocates mutual respect, harmonious coexistence and peaceful dialogue between different ethnic groups, cultures and religions, and fights against racism, religious extremism, cultural hegemony, the clash of civilizations, and all other unfavorable factors endangering social and world harmony. In recent years, the Chinese Islamic community has carried out a comprehensive interpretation of Islamic scriptures and other work, dug into its own cultural traditions for ideological resources with modern value and inherent potentials to adapt to social development, and interpreted such to the benefit of human development and social harmony, all to provide positive and healthy spiritual power and psychological support for the modernization of various nationalities. This is done to achieve unity among religion, society, and nation states. It can be said that Islam not only has positive impact on the ideological and ethical progress of Chinese society, but has also become an important part of it.

III. Conclusion

Human culture is always in a dynamic change process due to its own social development or cultural contacts. This is a regular phenomenon of cultural development. As an important part of human culture, religious culture has the same change characteristics during its spreading-out and development, i.e., it not only has impact on the culture of the area in question, but it also experiences a localization process due to shaping by local culture, in order to seek its own survival and continuity. As a religion, ideology, and cultural system, Islam interacts and integrates with local traditional cultures after being introduced into various parts of the world. As a result, a two-way interaction situation forms. On the one hand, in different historical conditions, Islamic culture has varying degrees of influence on social development, political structure, economic patterns, cultural fashion, ethics & morals, and lifestyles of many countries and ethnic groups; on the other hand, on the premise of adhering to its core doctrines, basic ibadat, and standard of value, it absorbs factors and expressions conducive to its own development from other cultures, and changes them reasonably, to adapt to the local social and cultural environment. Islamic culture was introduced into China in such a context.

In the contemporary globalization and modernization, Islam is not only the core content of the spiritual life of Muslim nationalities, but also their own potential cultural dynamic for them to choose a distinctive modernization pattern. Of the value orientation of Islam, peace, justice, equality, harmony, and other concepts are its permanent reality and ideals. At the same time, its advocate of benevolence, unity & mutual aid, hard work, and auspiciousness for the life of this world and for the hereafter provides a steady stream of spiritual motivation for the local Muslims to improve their quality of life and dedication to the development of ethnic groups, local society, and the nation. The Muslim community shall, on the one hand, criticize and reflect on its conservativeness, closure, exclusiveness, internal factions, and other limitations unhelpful to such development; while, on the other hand, the Muslim community needs to further demonstrate ethics and morals, value orientation, and real-life pursuance of Islam beneficial to the development of human society, enabling the general public to have a new objective and just understanding of Islam, in order to promote the healthy development of Islam in China.

References

1) Yang Huaizhong and Yu Zhengui (eds.), Islam and Chinese Culture, Ningxia People’s

Publishing House, 1995 (楊懐中、余振貴主編 『伊斯蘭与中国文化』、寧夏人民出

版社、 年).

chuan Lexicographical Publishing House, 2007 (中国伊斯蘭百科全書編集委員会編

『中国伊斯蘭百科全書』、四川辞書出版社、2007年).

3) Yang Wenjiong, Interaction, Adjustment and Reconstruction, Ethnic Publishing

House, 2007 (楊文炯 『互動・調適与重構』、民族出版社、2007年).

4) Ma Qiang, Floating Spiritual Community – Research on the Jamaat of Guangzhou Muslims from an Anthropological Perspective, China Social Sciences Press, 2007 (馬 強 『流動的精神社区―人類学視野下的広州穆斯林哲瑪提研究』、中国社会科学 出版社、2007年).

5) Annual Report on Religions in China (2009), Social Sciences Academic Press, 2009

(『中国宗教報告』(2009年)、社会科学文献出版社、2009年).

6) The China Islamic Association, An Overview of Islam in China, Religious Culture Publishing House, published in April, 2011, page 4 (中国伊斯蘭教協会編『中国伊斯 蘭教簡志』、宗教文化出版社、2011年4月、第4頁).

7) Ji Fangtong, “Research on the Structural Features and Employment Status of Floating Muslims in the Eastern Cities – Taking Tianjin, Shanghai, Nanjing, and Shenzhen cit- ies as Observation Points,” Journal of Second Northwest University for Nationalities (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), No. 4, 2008 (季芳桐 「東部城市流動穆斯 林人口的結構特征与就業状況研究―以天津、上海、南京、深圳四城市為考察点」、

『西北第二民族学院学報(哲学社会科学版)』、2008年第4期).

8) Yang Zongde, Study on Current Muslim Populations in China, Jinan Muslim, No. 2,

2010 (楊宗徳 「中国穆斯林当前人口研究」、『済南穆斯林』2010年第2期掲載).

Notes

1) Compiled by the China Islamic Association, An Overview of Islam in China, Religious Culture Publishing House, published in April, 2011, page 4.

2) Ibid., 2011, page 10.

3) Yang Zongde, Study on Current Muslim Population in China, published in Jinan Muslim, No. 2, 2010.

4) Compiled by the China Islamic Association, An Overview of Islam in China, Religious Culture Publishing House, published in April, 2011, page 159.

5) Ibid., 2011, pages 82-85.

6) Wang Yujie, “A Survey of Islam in China in 2008 and Analysis on Floating Muslims,”

published in Annual Report on Religions in China (2009) edited by Jin Ze and Qiu Yonghui, Social Sciences Academic Press, published in 2009, page 76.

7) Ji Fangtong, “Research on Structural Features and Employment Status of Floating Muslims in the Eastern Cities – Taking Tianjin, Shanghai, Nanjing and Shenzhen cit- ies as Observation Points,” Journal of Second Northwest University for Nationalities (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), No. 4, 2008.