Atsuko Takase and Kyoko Otsuki

要 旨

昨 今 、 入 学 形 態 が 多 様 化 し、 大 学 生 の 英 語 力 低 下 が 問 題 に な っ てい る。 入 試 対 策 中心 の 文 法 偏 重 授 業 の 影 響 か 、 中高 英 語 の イ ンプ ッ ト不 足 が 原 因か 、 中学 ・高 校 で 英 語 嫌 い とな り英 語 学 習 を怠 り、 基 礎 力 が 身 につ か な い ま ま大 学 に入 学 して くる学 生 が 増 えて きた 。 そ の た め、 大 学 の 授 業 で は学 力 不 足 で 単 位 取 得 が で きず 再 履 修 生 とな る学 生 が 増 え て きてい る。 これ まで 、 再 履 修 ク ラス に代 表 され る リメ デ ィアル ク ラス の 授 業 で は、 基 礎 文 法 ・語 彙 ・平 易 な会 話 ・ビ デ オ教 材 等 が 多 く採 用 さ れ て きた。 は た して 、 そ れ まで 主 に文 法 で 蹟 い て英 語 嫌 い と な っ た学 生 が 、 新 た に英 文 法 を学 び直 す 意 欲 を起 こす で あ ろ うか 。 ま た、

上 記 の様 な教 材 で 、 どこ まで 英 語 力 を向 上 させ 、 英 語 運 用 能 力 を 身 に付 け る こ とが で きる か 疑 問 で あ る。 この 研 究 で は、 再 履 修 の 学 生 に多 読 授 業 を行 っ た結 果 、 学 生 が や る気 を起 こ し3ヵ 月で100冊 を超 え る大 量 の 本 を読 み 、 事 後 テス トで 英 語 力 向 上 が 認 め られ た こ と を報 告 す る。

Introduction

Recently, there has been much interest in the concept of remedial education in Japan. As one of the reasons, it has been long discussed that the academic standard of students at higher education is dropping in the last few decades. It is generally said that the followings are considered to be the major causes. First, due to yutori-kyoiku or pressure-free education, whereby the hours and the content of the curriculum were reduced in primary and secondary school education, school pupils do not have enough time to acquire basic knowledge or skills necessary for studying at colleges or universities. Second, the decrease of the number of children in the country enables those with relatively lower ability to enter colleges or universities. Accordingly, at some institutions it is necessary to improve the academic ability of these students for study at college and university level.

According to the survey by Shinken Ado and Sundai Kyoiku Kenkyujo (1999), remedial education at universities and colleges in Japan is categorized into four types:

(1) providing students with classes for subjects which students have not studied at

ft* • i-liftefft

secondary school, but are necessary for their work at higher education institutions; (2) providing students with preparatory sessions as an introduction to subject areas in question; (3) providing students with the above-mentioned courses as pre-sessional courses prior to the official entrance to the institution; and (4) providing students whose academic performance is not good enough for further work with supplementary or review courses. In this paper, we treat the last category which is generally referred to as repeater courses.

Meanwhile, more publishers are putting textbooks on the market for remedial courses which mainly deal with basic grammar under the name of "Basic English" or

"E

ssential English Grammar." Thus, the focus of English remedial classes seems to be on the formal teaching of grammar. The limitation of all these types of implementation is that it is often ignored that learners who attend remedial courses have already had painful experiences with English at an earlier stage of their study, i.e., English classes at junior and senior high school, where the formal teaching of grammar is broadly implemented. They have found the subject uninteresting or boring, and some of them even hate it. On the other hand, there are always several repeaters who fail their course for other reasons than the lack of English proficiency. They are often highly motivated to study English and possess good knowledge of grammar. Therefore, the impact of having another opportunity to study basic grammar in repeater courses at college or university seems dubious for both types of students.

Additionally, the question remains whether repeater courses concentrating on grammar are successful; in other words, it is not always clear whether learners who completed remedial coursework show any development in their proficiency of English.

In the current repeater courses, obtaining the credit is considered as success of the

"

remedy." However, completing the course does not always indicate that the English ability of students has improved.

The aim of this paper is to explore the possibilities of extensive reading (henceforth ER) as an alternative to the current approaches found in remedial courses. ER is theoretically based on the idea of the Chomskyan model of first language acquisition. In this model, first language acquisition is made possible through children being exposed to numerous examples of the language. The grammar of the language consists of principles and parameters, and the latter is to be set by input of the language in question (Chomsky, 1981). It was suggested that the same process could apply to

— 332 —

second language acquisition (Cook, 1991; Krashen, 1982). In Japan, most learners of English are not fortunate enough to receive enough input of English to set the parameters of English grammar. Following the process of first language acquisition, ER aims to provide learners with an opportunity to relive the stage of receiving a substantial amount of input in the target language. Thus, through being exposed to a huge amount of English in context, ER aims for learners to acquire English which they can manipulate.

ER has been implemented for the last decade as an alternative approach to reading practice as opposed to the traditional grammar-translation method or a supporting method to reinforce reading skills. It has been gaining in popularity across Japan as one of the most effective methods to improve learners' English proficiency. A positive effect of ER on learners' English ability, along with their motivation to read English, has been suggested (e.g., Cho & Krashen, 1994; Elley & Mangubhai, 1981; Hafiz

& Tudor, 1989; Mason & Krashen, 1997; Robb & Susser, 1989; Suzuki, 1996; Takase, 2004).

Traditionally, English teaching in Japan has centered around the grammar- translation method. In this method, learners read English texts by translating them word by word; therefore, efforts are mainly made to analyze the structure of complex English sentences using the knowledge of grammar, rather than appreciate the contents of the text. Learners are devoted to making good Japanese translation. In fact, what matters appears to be the outcome of the translation, i.e., Japanese sentences.

Consequently, comprehension of the text is made through Japanese. The knowledge of the grammar is allegedly reinforced through subsequent exercises where the question sentences are taken out of context. Then, the knowledge of grammar seems not to directly serve as a basis for actual communication.

In contrast, learners in an ER program read numerous books in English without using a dictionary or translating them into Japanese. The level of English is relatively low, compared with that of English in textbooks adopted in the grammar-translation method. The advantage of reading simple English is to enable learners to comprehend the English text as it is, not in the form of Japanese translation. In short, ER aims to promote the ability to read English, focusing on enhancing fluency rather than accuracy.

Table 1 summarizes the differences between the traditional reading approach and ER.

Table 1. Differences between traditional approach to reading and ER

Item Traditional approach ER

Choice of textbooks Material & level Amount of reading Manner of reading English in text Speed of reading Manner of comprehension

By teachers Same Limited

Partial, fractional Relatively Complex Slow

Via translation

By learners Various Substantial Comprehensive Relatively simple Fast

As it is (without translation) (Partially taken by Takase, 2010, p.24 and translated by the authors)

There are two crucial factors to follow in order to lead a successful ER program.

First, learners start to read books written in easily comprehensible English (Start with Simple Stories, henceforth SSS). By reading relatively easy English, learners form a habit of reading English as it is, breaking the habit of translating English into Japanese for its comprehension. As learners are usually used to reading an English text consisting of several paragraphs from their grammar-translation method experience, reading through a whole English book can be a source of confidence. Moreover, learners who read many relatively easy books at the early stage of their ER experience show a smooth development of their reading proficiency (Takase, 2007; 2009a).

Second, it is crucial to secure a certain amount of time for reading. According to Krashen (1993), reading proficiency can be improved by free voluntary reading (FVR) in the second or foreign language as well as in the learners' first language (L1).

Sustained Silent Reading (henceforth SSR) is one kind of FVR, which refers to any in- school program where students are provided a short time for reading without any after-reading requirement. The effectiveness of SSR on learners' reading proficiency development in their Ll has been reported by many teachers and practitioners (e.g., Henry, 1995; Pilgreen, 2000) as well as in the learners' second or foreign language

(Nishizawa et al., 2006; Sakai & Kanda, 2005; Takase, 2008; 2009b; 2010a; 2010b). SSR aids in bridging the gap between the beginning and advanced levels by consolidating the learners' foundation in the language and allowing them to acquire higher levels of proficiency (Krashen, 1993). Takase (2008) points out that along with SSS, SSR played an important role in motivating her high school and university students to read

— 334 —

extensively. Obtaining time not only makes it possible for students to concentrate on ER, but also enables teachers to observe how learners read books and demonstrate the importance of reading (Day & Bamford, 1998; Krashen, 2004).

As mentioned above, it has been reported that ER has an effect on improving English proficiency, when SSS and SSR methods are employed, in particular. The major effects of ER can be summed up as the following four aspects:

(1) Improving English proficiency

Along with the reading proficiency, it is reported that listening, writing and speaking abilities are improved through ER in some cases (Takase, 2010a).

Moreover, ER has an effect on vocabulary (Waring & Takagi, 2003; Yamazaki,

1996) and spelling (Polak & Krashen, 1988; Day & Swan, 1991).

(2) Increasing learners' confidence in reading English

As reading rather easy books is encouraged in extensive reading, it will be possible to remove students' Affective Filter (Krashen, 1982).

(3) Promoting an understanding of foreign cultures

Books adopted in ER courses often contain descriptions of daily life and customs in the culture in which the target language is spoken (e.g., garage sale or car

boot sale; Independence Day, Guy Fawkes Day). These descriptions can serve as an unpretentious introduction to foreign cultures.

(4) Forming a reading habit

Learners who have read many books feel a sense of accomplishment, which in turn motivates further reading (Takase, 2004).

Considering the effects of ER reported so far, this paper investigates the impact of ER on students in repeater courses, examining whether ER encourages learners in repeater courses to read English books and has an effect on their English proficiency.

Thus, the following research questions are posed:

1) Is extensive reading effective to motivate learners to read in remedial courses which consists of students with various proficiency levels?

2) Do learners in repeater courses make progress in their English proficiency after three months of extensive reading?

ft*.NAMIt1-37—CV

Method

Participants

The participants in this study were 81 (69 male, 12 female) 1st- 4th year non- English major EFL university repeaters from two consecutive years (2009 & 2010) who had failed to pass the former English course. Unlike the previous intact classes they had been enrolled in, the repeater classes were mixed ability classes. Their TOEIC scores, which 53 participants out of 81 (65.4%) took during the past few years, varied from 190 to 625 (M = 355, SD = 106.7). According to the survey which was administered at the beginning of the class, the major reasons for their failure were lack of English ability to pass the test and a lack of attendance. As multiple selections were available, 36 students (44.4%) chose lack of English ability and 36 students (44.4%) chose a lack of attendance. Among these students, 22 of them (27.2%) chose both items, referring to the difficulties of the lessons. It can be assumed that these students found their lessons difficult to follow and became reluctant to attend the class. Among the 52 participants (64.2%) who responded that they were poor at English, 53.8% of them admitted that they had difficulty in understanding grammar, followed by reading with the grammar-translation method and listening at 30.8% and 26.9%, respectively. More than half of the repeaters (43) with low self-esteem had been suffering from low- performance and poor academic grades in English since junior high school (34.9%) or senior high school (53.5%) and university (11.6%). Students who indicated their failure to be attributed to lack of attendance admitted that they were not able to attend classes due to their busy lifestyle with mainly part-time jobs and other social activities.

Procedure

All the students participated in ER for one academic semester, approximately three months. The classes met once a week totaling 14 sessions in a designated room in the library. At the onset of the course, ER was introduced in order to raise student awareness of the necessity and effectiveness of reading English books extensively with the emphasis on experiencing the joy of reading. During the class students were occupied with SSR, for approximately 80 minutes with reading and 10 minutes for keeping their reading log. It should be noted that SSR in this paper is not the pure SSR defined by Krashen (1993) mentioned above, but a modified SSR in that the teacher observed students' reading and checked their reading log before they engaged in

— 336 —

reading with their students, and the time for SSR concerned is much longer than what he defined.

The participants were required to read at least 100 easily comprehensible books during the course, and to keep a reading log of every book they read including the date, title, series, level, and word count of each book, the time used for finishing the book, and a short impression or remark about the book. Most of the higher level students were suggested to choose books which were appropriate to their level, once they became used to reading without translation. They were required to read 50,000 to 100,000 words depending on their proficiency level, instead of reading 100 books. During the time for SSR, participants were given individual guidance when necessary.

The Edinburgh Project on Extensive Reading (EPER) cloze test (version A) was administered at the beginning and the end of the course as the pre- and the post-tests, in order to examine the improvement of participants' overall reading proficiency. Thus, the number of sessions participants were given for SSR was 12.

Two kinds of reading materials were used: 1) leveled readers (LR) and picture books for Ll children published by Oxford, Longman, Random House, Scholastic, Usborne and other major publishers; and 2) graded readers (GR) containing vocabulary ranging from 200 to 1200 headwords. They were mainly Foundations Reading Library (FRL) by Cengage, Macmillan Readers (MMR) by Macmillan, Oxford Bookworms (OBW) by Oxford, and Penguin Readers (PGR) by Pearson Longman.

Results and Discussions Data Analysis

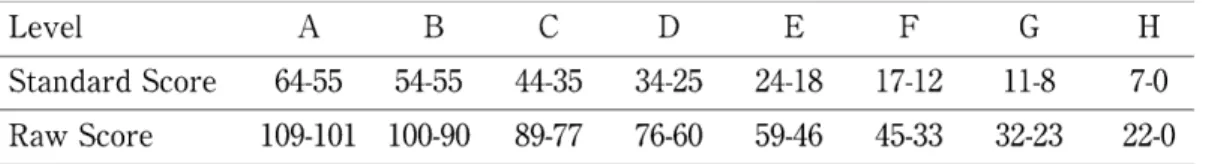

First, the raw scores of the EPER Placement test (Version A) were converted to the standard scores, and then they were classified from A to H (EPER level) according to the criteria given by EPER, A being the highest and H being the lowest (Table 2).

Based on the EPER pre-test, the participants were divided into three groups for analysis: upper level (over F), middle level (F), and lower level (G & H) .

ft* • i-liftefft ^ 37—CV

Table 2. EPER score and level conversion table

Level A B C D E F G H

Standard Score 64-55 54-55 44-35 34-25 24-18 17-12 11-8 7-0

Raw Score 109-101 100-90 89-77 76-60 59-46 45-33 32-23 22-0

Second, the descriptive statistics of the EPER cloze test scores for the pre- and the post-tests for each group were calculated using the standard scores.

Third, in order to investigate the differences of reading amount and reading style between the three groups, the reading volume of the participants was calculated in terms of the number of books read, the number of words read, and the average word count per book which each group of students read during the semester.

Lastly, the effects of ER on overall reading proficiency were examined using the one-way repeated-measures factorial ANOVA.

Distribution of the number of participants in the EPER level.

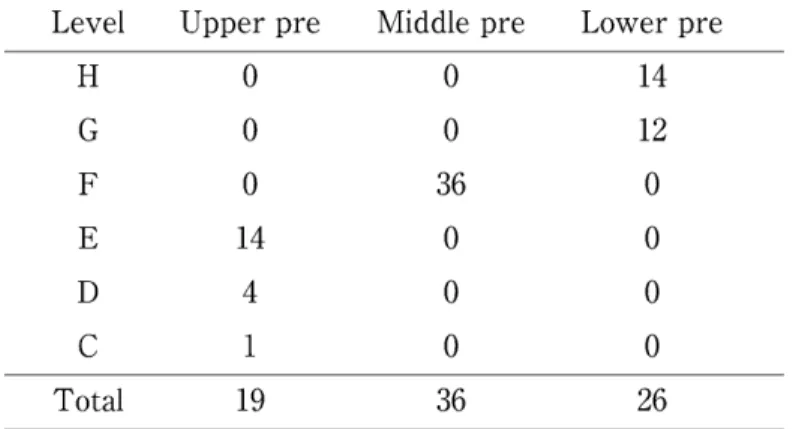

Based on the pre-EPER level, participants were divided into three groups for analysis: upper level (N = 19), middle level (N = 36), and lower level (N = 26) (Table 3). As the participants in the repeater courses consisted of several high level students and many low level students, as many as 36 (44%) students were classified in the same EPER level F, participants over F were included in the upper class, and those lower than F were placed in the lower class, therefore, the numbers of each group were not even. Table 3 illustrates the distribution of participants in three groups who were placed in each EPER level based on the result of the pre-EPER test. The upper group consists of EPER levels E and over, F in the middle group, and H and G were in the lower group. There were no participants who scored high enough to be placed as A or B.

— 338 —

Table 3. No of students in the EPER pre-test level in 3 groups

Level Upper pre Middle pre Lower pre

H G F E D C

0 0 0 14

4 1

0 0 36

0 0 0

14 12 0 0 0 0

Total 19 36 26

Descriptive statistics.

Table 4 illustrates the descriptive statistics of the pre- and the post-EPER tests, which were administered at the beginning and at the end of the course. The mean standard scores of the EPER tests were, from upper group to lower group: 23.2 (SD = 5.49), 14.6 (SD = 1.66), and 7.4 (SD = 2.25) for the pre-test, and 28.5 (SD = 5.34), 19.2

(SD = 4.10), and 12.2 (SD = 5.28) for the post-test, respectively, with a great variance of scores between upper and lower groups.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics for the EPER pre- and post-tests

Group N Mean SD Min Max

Upper pre Upper post Middle pre Middle Post

Lower pre Lower post

19 19 36 36 26 26

23.2 28.5 14.6 19.2 7.4 12.2

5.49 5.34 1.66 4.10 2.25 5.28

18 21 12 11 3 2

40 43 17 29 11 23

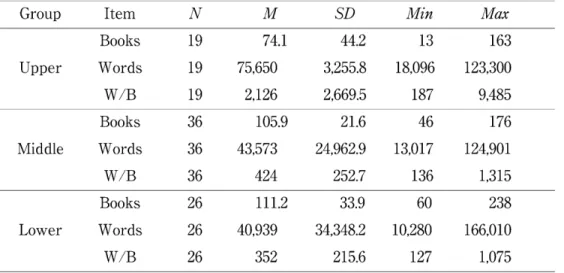

Participants' reading performance.

RQ 1. Is extensive reading effective to motivate learners to read in remedial courses which consists of students with various proficiency levels?

Table 5 shows the participants' reading performance in terms of the number of books and words and the average word count per book.

ft* •

Table 5. Participants' reading performance

Group Item N M SD Min Max

Upper

Books Words W/B

19 19 19

74.1 75,650

2,126

44.2 3,255.8 2,669.5

13 18,096

187

163 123,300

9,485

Middle

Books Words W/B

36 36 36

105.9 43,573

424

21.6 24,962.9

252.7

46 13,017

136

176 124,901

1,315

Lower

Books Words W/B

26 26 26

111.2 40,939

352

33.9 34,348.2

215.6

60 10,280

127

238 166,010

1,075

The upper group read the largest number of words, 75,650, on average and the smallest number of books, 74.1, resulting in 2,126 words per book. On the other hand, both the middle and the lower groups read relatively large number of books; 105.9 and 111.2 with smaller numbers of words; 43,573 and 40,939, respectively, which makes relatively a smaller word count per book; 424 words for the middle group and 352 words for the lower group. These results suggest that participants in the upper group read longer books with more than 2,000 word count on average, whereas those in the middle and the lower groups read over 100 shorter books which contained less than 500 words, which were appropriate to their English proficiency level. Participants in the middle and the lower groups with low English proficiency were motivated to read over the required number (100) of books, as they chose relatively short and easy books, whereas the participants in the upper group chose longer books which were appropriate to their English proficiency level. Thus, extensive reading was effective to motivate learners of remedial courses to read which consisted of students with various proficiency levels.

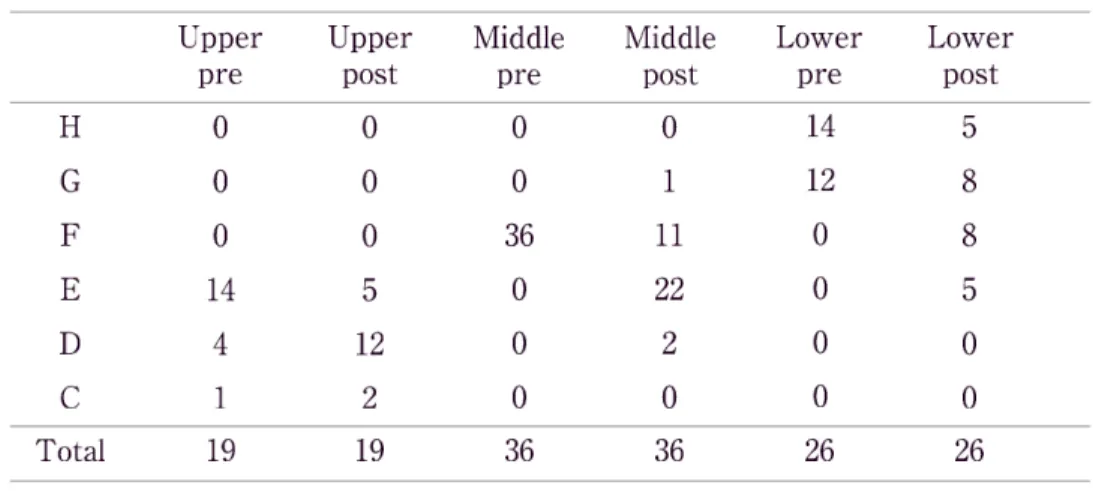

Change of distribution of EPER level on the EPER post-test.

RQ2. Do learners in repeater courses make progress in their English proficiency after three months of extensive reading?

In order to examine the changes of EPER levels in the EPER post-test, standard scores were classified into A to H based on the EPER pre- and the post-test scores in three groups; upper, middle, and lower (Table 6, Figure 1).

— 340 —

Table 6. Change of distribution in the EPER post-test level Upper

pre

Upper post

Middle pre

Middle post

Lower pre

Lower post H

G F E D C

0 0 0 14

4 1

0 0 0 5 12

2

0 0 36

0 0 0

0 1 11 22 2 0

14 12 0 0 0 0

5 8 8 5 0 0

Total 19 19 36 36 26 26

14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0

^ Pre

^ Post

40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0

^ Pre

^ Post

14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0

^ Pre

^ Post

HGFEDC Upper group

Figure 1.

-HGFEDC HGFEDC

Middle group Lower group

Changes in the distribution of EPER level in three groups

As seen in Table 6 and Figure 1, participants in all three groups gained greatly on the post-test. As a result, all the students excluding a couple of exceptions moved up to higher EPER levels. In order to examine statistically more in detail, repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted on the EPER pre- and the post-test scores.

Repeated-measures ANOVA on the EPER pre- and the post- tests.

The effects of extensive reading on overall reading proficiency were examined using a two-way repeated-measures factorial ANOVA. Table 7 summarizes the repeated-measures ANOVA on the EPER pre- and the post-test scores. The between- subjects factor was groups (upper, middle, lower) and the within-subjects factors were the EPER pre- and post-test scores.

ft* • —CV

Table 7. Repeated-measures ANOVA on the EPER pre- and post- tests

Source SS df MS F p

Between Subjects Group

Error Total

5648.70 1991.24 7639.94

2 78

2824.35 25.53 2849.88

110.63 .000**

Within Subjects EPER Test EPER x Group Error

Total TOTAL

908.81 2.31 572.15 911.12 8551.06

1 2 78

908.81 1.15

7.34

123.90 .16

.000**

.855

**p < .0001

As seen in Table 7, the results of the analysis indicated a significant main effect for each group (F = 110.63, df = 2, p = .000), a significant main effect for the EPER test (F =123.90, df = 1, p = .000), and an insignificant interaction effect between the EPER test x group (F = .16, df = 2, p < .855). The results revealed that there were significant between-groups differences, significant changes between the pre- and the post-EPER tests, but the EPER test factor and group factor showed no interaction. This can be seen in the parallel lines in Figure 2.

30 22 --a--

8 20 cn

Group

2 io .... Upper

o Middie

"." Lower 0

1 Ti me2

Figure 2. Changes in the EPER pre- and post-test scores

Figure 2 shows the changes of the EPER pre- and the post-test scores of three groups (upper, middle, lower). Parallel lines indicate that the two factors were not interacting. The results revealed that each group showed a significant improvement in

— 342 —

English proficiency after only three months of ER using SSS and SSR methods in the library, even though their proficiency levels were quite varied. Participants chose books which were appropriate to their English ability with the help of the instructor. ER was effective for all levels of repeaters for improving their English proficiency when they were occupied with SSR for 80 minutes a week, in particular.

Conclusion

From the results of this study, it can be concluded that repeaters from the remedial group with low English ability, who were not able to pass the test due to their lack of English ability, to higher level students, who had failed for reasons other than English proficiency including lack of motivation, benefited from ER using SSS and SSR methods. Although the length of the program was only three months, all the participants were motivated to read English books. Participants from the middle and the lower groups succeeded in reading more than 100 English books, and the upper group members read approximately 76,000 words on average in three months. The effects of reading in quantity were illustrated as gains on EPER test scores in all three groups. Each group showed significant gains in the EPER post-test scores, attributed to the ample time for SSR provided under the guidance of an instructor. In conclusion, extensive reading can be one of the most effective approaches to motivate students in repeater classes which consist of different kinds of remedial students to read extensively and thereby improve their overall English proficiency as well as attitudes toward English.

This study is subject to some limitations. First, as the number of participants was small, it was not advisable to divide them into three groups. However, in order to investigate the effectiveness of extensive reading on both low level repeaters and high level repeaters, it was necessary to split the group into three: upper, middle, and lower.

Second, the number in each group was not even due to the huge gap between the high level students and low level students. As there were a small number of high level students and a large number of middle level students, it was difficult to draw a line in the middle of them. These problems should be solved with a larger number of participants in future research.

ft*.NAMIt1-37—CV

References

Cho, K. S., & Krashen, S. D., (1994). Acquisition of vocabulary from the Sweet Valley Kids series: Adult ESL acquisition. Journal of Reading, 37(8), 662-667.

Chomsky, N. (1981). Lectures on government and binding. Dordrecht: Foris.

Cook, V. (1991). Second language learning and language teaching. London: Edward Arnold.

Day, R., & Bamford, J. (1998). Extensive reading in the second language classroom.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Day, R., & Swan, J. (1991). Reading and spelling competence: Evidence from an EFL context. Unpublished manuscript.

Elley, W. B., & Mangbhai, F. (1981). The impact of a book flood in Fiji primary schools.

New Zealand Council for Educational Research and Institute of

Education: University of South Pacific.

Hafiz, F. M., & Tudor, I. (1989). Extensive reading and the development of language skills. ELT Journal, 43(1), 4-13.

Henry, J. (1995). If not now: Developmental readers in the college classroom. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook, Heinemann.

Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Oxford:

Pergamon.

Krashen, S. D. (2004). The power of reading: Insights from the research (2nd ed.).

Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Mason, B., & Krashen, S. (1997). Extensive reading in English as a foreign language.

System, 25 (1), 99-102.

Pilgreen, J. L. (2000). The SSR Handbook: How to organize and manage a sustained silent reading program. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook, Heinemann.

Polak, J., & Krashen, S. (1988). Do we need to teach spelling?: The relationship between spelling and voluntary reading among community college ESL students.

TESOL Quarterly, 22(1), 141-146.

Robb, T. N., & Susser, B. (1989). Extensive reading vs skills building in an EFL context.

Reading in a Foreign Language, 5, 239-251.

Shinken Ado and Sundai Kyoiku Kenkyujo (1999). Remedial kyoiku ni kansuru jittai chosa [A survey into the state of remedial education.]

Takase, A. (2004). Investigating Students' Reading Motivation through Interviews.

— 344 —

Forum for Foreign Language Education, 3. Institute of Foreign Language Education and Research. Kansai University.

Takase, A. (2007). Effects of Easy Books on EFL Students' Reading Proficiency. Paper Presented at JALT Conference 2007.

Takase, A. (2008). The two most critical tips for a successful extensive reading program. Kinki University English Journal, 1, 119-136.

Takase, A. (2009a). The effects of different types of extensive reading materials on reading amount, attitude and motivation. In A. Cirocki (Ed.), Extensive

reading in English language teaching (pp. 451-465). Munich, Germany:

Lincom.

Takase, A. (2009b). The effects of SSR on learners' reading attitudes, motivation, and achievement: A quantitative study. In A. Cirocki (Ed.), Extensive

reading in English language teaching (pp. 547-560). Munich, Germany:

Lincom.

Takase, A. (2010). The effectiveness of Sustained Silent Reading in helping learners become independent readers, Proceedings of 37th MEXTESOL

International Convention/10th Central American and Caribbean

Convention.

Waring, R., & Takaki, M. (2003). At what rate do learners learn and retain new vocabulary from reading a graded reader? Reading in a Foreign

Language, 15, 1-27.

Yamazaki, A. (1996). Vocabulary acquisition through extensive reading. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Temple University, PA.

N4TI* • *III tcc,774,Vt- (2005) . rtc&V,AtrX7iff 100t---,A 0)1-1-66 —.1 tom,4,m.

3107 J •g-e-AVUZsifi (1999) I-1) )4 :7-='-f 7)1,ft z

g-,,7— (1996) . ply 0DV L 660D Nfi-Lor,,t,7?ko

Th'34-1 (iliDR) pp. 116-123. E

Ni --- • Q MAI • 914fri* (2006) . zig-Aq-to-y*-2,-Antjj&c

IEEJ Trans. FM. 126 (7), pp. 556-562.

(2010b). FAII-14,1: • 14M3-4-`v,--=- .3- 7 )1/il