J.AnthroP. Soc. NipPon 人 類 誌 100(3):349-358(1992)

MATERIALS

A Decapitated Human Skull from Medieval Kamakura

Iwataro M0RIM0TO and Kazuaki HIRATA

Department of Anatomy, St. Marianna University School of Medicine

Abstract The present study reports on the examination of a decapitated human male skull with four upper cervical vertebrae and the hyoid bone, dating to the early

Muromachi period (late 14th century), from Kamakura. The decapitation may have

been the result of a sharp cut from the right rear. The cut runs horizontally into the

second cervical vertebra and stops in the bone, after having severed both the spinal

cord and the right vertebral artery. Superficial injuries to the skull were probably

not the primary cause of death. The head was separated from the body post mortem,

probably as a result of an additional cut noted in the fourth cervical vertebra. It is

suggested that the traditional Japanese method of decapitation in former times may

be characterized by a cut halfway through the neck, and this method of decapitation

can be traced back to the early Muromachi period.

Key Words Decapitation, Cut injury, Cervical vertebrae, Medieval Muromachi period. Japanese tradition

Material

The decapitated skull reported here (no. 1043) was excavated from location D-197 of the Yuigahama Medieval Cemetery, Kamakura, in 1991, under the supervision of Mr. Hiroshi HA. Two additional decapitated human, male, skulls from another site in Kamakura have been previously reported by MORIMOTO (1987). This site dates to the early Muromachi, or Namboku-cho period (late 14th century). The skull with four upper cervical vertebrae and the hyoid bone, were the only bones recovered from this individual. The cervical vertebrae are not present in most decapitation specimens dis-covered. The skull with the injured vertebrae, presented in this report, are interesting and

valuable discoveries. They may be useful in con-tributing to an explanation of the origin of the traditional Japanese method of decapitation.

Observations

The excavated bones were in good condition with a well preserved internal architecture. There was no closure of the coronal, lambdoid or sagittal sutures on both external and internal surfaces of the cranial vault, although upper and lower third molars, with slight wear, could be seen on both sides. Therefore the male of this skull would have been in his early twenties at the time of death. The paleopathological observa-tions concerning the method of decapitation obtained are given in the following description.

A dozen injuries, probably resulting from a

350 I. MORIMOTO and K. HIRATA

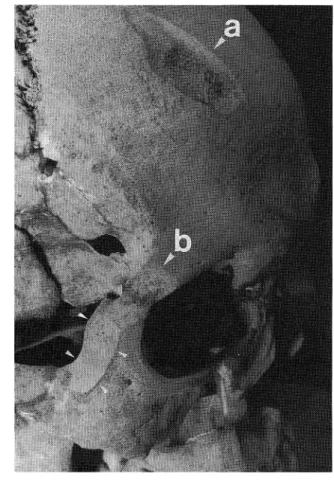

Fig. 1. The upper part of the facial skull, viewed from the right front. Note the injuries to both frontal

squama (a) and right orbital region (b), which took

the form of superficial incisions.

Japanese sword with a keen edge, were found in both the skull and the cervical vertebrae. The skull had six injuries. An injury to the frontal squama on the right side was 45mm in length, running in an oblique direction from the right rear to the left front (a in Fig. 1). The injury took the form of superficial incisions, having an in-clined cut surface from the external table to the diploe of the squama, accompanied with a secondary loss of bone opposed to the cut sur-face. Another injury to the anterior border of the lateral wall of the right orbit grazed the bone. The

area involved is from the right zygomatic pro-cess of the frontal bone to the frontal propro-cess of the right zygomatic, although the cut surface was divided into two small facets by a faint transverse ridge (b in Fig. 1). One more injury to the right parietal bone ran in an almost sagittal direction below, and parallel to, the right temporal line (c in Fig. 2). The entire length of this injury could not be determined, because most of the cut surface and its neighboring area had been broken and lost. It was, however, conceivable that the cutting by the sword took the form of a kind of

A Decapitated Human Skull from Medieval Kamakura 351

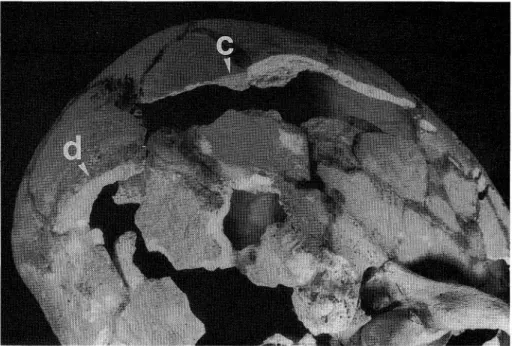

Fig. 2. The cranial vault, viewed from right-inferior-rear. Note the injuries to both the right parietal (c) and the occipital (d) bones. The former took the form of a kind of gash, tangentially

reaching the cranial cavity to a slight degree, whereas the latter cut off the right inferior nuchal line, causing a break of the neighboring nuchal plane.

gash, tangentially reaching the cranial cavity to a slight degree.

All the above three injuries to the skull showed the clear-cut unhealed nature of the wound, so that they would have been made just before death. Because the injuries failed to reach the interior of the skull, they could not be regarded as the primary cause of death. Moreover, there were three other injuries to the skull; one to the occipital bone, and two to the mandible. The injury to the occipital bone cut off the right inferior nuchal line in a slightly inclined plane from right cranially to left caudally, causing a break of the neighboring nuchal plane, although the sword did not enter into the cranial cavity (d in Fig. 2). It was uncertain whether the occipital bone received the injury during life or after death. The two injuries to the mandible were a pair of

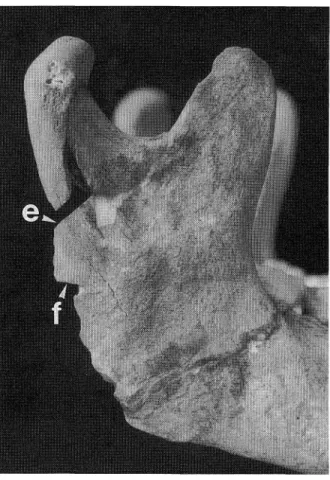

upper and lower transverse cuts from the right rear on the posterior border of the right mandi bular ramus. The upper transverse cut ran somewhat obliquely from the lower rear upward toward the front (e in Fig. 3), whereas the lower injury passed in a nearly horizontal direction (f in Fig. 3). These injuries corresponded to the two cut surfaces in the second cervical vertebra or axis (j and h in Fig. 5) mentioned below.

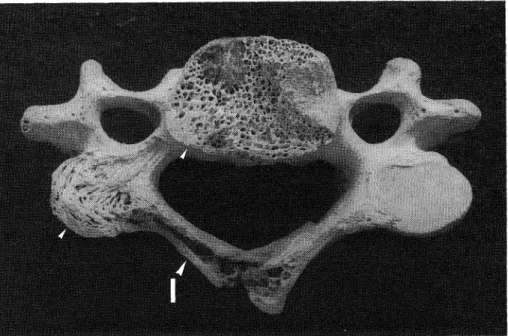

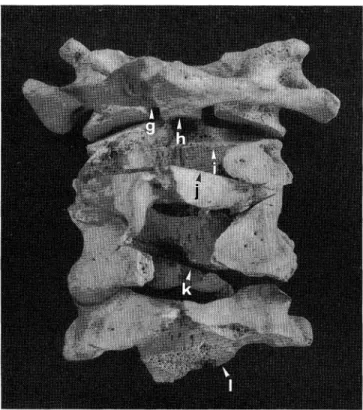

The upper four cervical vertebrae had six injuries due to five cuts with the sword. The first cervical vertebra, or atlas, was cut horizontally from behind. This chipped off the lower border of the posterior part of the vertebral arch of this bone (g in Fig. 4). The cut surface in the atlas corresponded to the most superior cut in the axis as mentioned next. The axis was cut horizontally from the right rear three times by the sword, so

352 I. MORIMOTO and K. HIRATA

Fig. 3. The right mandibular ramus, viewed from the right. The injuries (e) and (f) in this bone respectively

corresponded to those to the axis (i) and (h), which are shown in Fig. 5.

that the bone had three cut surfaces. These cut surfaces were laid at three different levels in this bone. The most superior cut surface was located on the posterior portion of the base of the odontoid process or dens (h in Fig. 5), and the second superior cut surface was running through both the upper portion of the vertebral arch and the posterior half of the right superior articular process about half a centimeter below the level of the most superior cut (i in Fig. 5).

Both the most superior and second superior cut surfaces stopped anteriorly at the central parts

of the dens and vertebral body, so that there was a loss of the dens and vertebral body between the two cut surfaces. Because the plane of the most superior cut surface in the axis corresponded to that of the above-mentioned lower cut on the posterior border of the right mandibular ramus (f in Fig. 3), it seemed that the cutting sword was stopped not only by the dens, but also by the right mandibular ramus. The most inferior cut surface in the axis was running through the spinous process and stopped in the vertebral arch of this bone, resulting in chipping off the bone

A Decapitated Human Skull from Medieval Kamakura 353

Fig. 4. The atlas, viewed from below. Note that the injury to this bone (g) corresponded to that to the axis (h) as shown in Fig. 5,

Fig. 5. The axis, viewed from above. Note the three injuries (h), (i) and Q) to this bone at the different levels. For explanation see text.

354 l.. MORIM0T0 and K. HIRATA

Fig. 6. The third cervical vertebra, viewed from the rear. Note the oblique injury (k) to the vertebral body through the right inferior articular processes and vertebral arch.

Fig. 7. The fourth cervical vertebra, viewed from below. Note the injury to this bone (1), which was stopped at the vertebral body after passing through the spinous and right inferior

articular processes.

A Decapitated Human Skull from Medieval Kamakura 355

above the cut surface (j in Fig. 5).

The most inferior cut surface was in a slightly inclined direction from the right rear to the left above. Because it corresponded to the upper cut on the posterior border of the right mandibular ramus (e in Fig. 3), it was probable that the cutting was also stopped by both the axis and the mandible.

The third cervical vertebra was cut from the right rear (k in Fig. 6). The cut surface passed obliquely from the right below to the left above, parallel to the lowest cut surface in the axis. It ran into both the vertebral arch and the body through the spinous and right inferior articular processes of this bone, and came to a stop at the left pedicle of the vertebral arch. As a result, the

spinous and right inferior articular processes and their neighboring area of this bone were cut off and lost.

Finally, the fourth cervical vertebra was cut horizontally from the right rear, the cut surface passing from the spinous and right inferior articular processes to stop on a straight line connecting the left inferior articular process with the left quarter of the vertebral body (1 in Fig. 7). The spinous and left inferior articular pro-cesses of this bone were thus cut off and lost. No injury was, however, found in the hyoid bone.

Discussion and Conclusion

+Considering the sword injuries to both the skull and the cervical vertebrae, the human male

Fig. 8. The upper four cervical vertebrae articulated, viewed from behind. Note the injuries to the atlas (g), to the axis (h), (i) and (j), and to the third (k) and fourth (1) cervical vertebrae ,

due to five cuts at various levels.

356 I. MORIMOTO and K. HIRATA

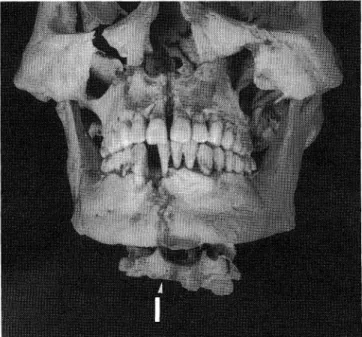

examined in this report died as a direct result of decapitation. The injuries to the frontal squama, the lateral wall of the right orbit, and the right parietal and occipital bones of the skull, as mentioned above, were probably not the primary cause of death. Since there were found five cut surfaces in the articulated cervical vertebrae of this male, it is difficult to determine the decisive injury from which he died when decapitated.

Of the five cuts, the lowest in the axis (j in Fig. 8) and the cut in the third cervical vertebra (k in Fig. 8) are to be excluded for two reasons. The first reason is that the cuts followed an oblique line running from the right rear to the left superior direction so that these cuts could not have resulted in a decapitation. The second reason is that the cut in the axis was too super-ficial to sever the spinal cord. The remaining three cuts in the neck can be divided into two, two upper and one lower. The upper two cuts (g + h

and i in Fig. 8) were concentrated on the atlas and the axis, while the lower cut (tin Figs. 8 and 9) passed into the fourth cervical vertebra. As previously mentioned by KAWAGOE (1965) and MORIMOTO (1981), the sword at the time of decapitation approached from behind and some-times missed the mark and cut into the occipital bone. This indicates that the junction of the skull and the vertebral column was the target of the sword for decapitation. It is, thus, natural to suppose that one of the two cuts in the axis of this male had a possibility of providing the fatal injury during decapitation.

Either of these two cuts could have taken his life, because it ran horizontally to reach a depth sufficient to sever both the spinal cord and the right vertebral artery. The second superior cut in the axis, as well as the cuts in the third and fourth cervical vertebrae, were on the other hand possibly made by the sword when the head was

Fig. 9. The skull and upper four cervical vertebrae articulated, viewed from front. Note that the cut to the fourth cervical vertebra

(I) was stopped after cutting into the bone.

A Decapitated Human Skull from Medieval Kamakura 357

separated from the body after death. This is based on three reasons as follows; l) the injuries to the atlas and dens were too high to separate the head from the body after death, and the mandible obstructed the cutting; 2) the injury to the third cervical vertebra ran in a direction difficult for decapitation, running obliquely from the right rear to the left above, almost parallel to the lowest cut in the axis as mentioned above; and 3) only the skull with the upper four cervical vertebrae and the hyoid bone remained, sug-gesting that the effective and final separation of the head was done by a cut into the fourth cervical vertebra.

The decapitated male may have been a seriously wounded warrior, or samurai, who had given up all hope of living, and was then assisted in committing suicide, either by his wish, or an order as a result of an unavoidable circumstance. In Japan at that time, the execution of a samurai was considered a disgrace, thus suicide by sword was viewed as an honorable way of dying. After the identification of the head, which had been separated and taken away from the body, it was buried at the Yuigahama Cemetery in Kamakura. At any rate, the observations ob-tained clearly show that the sword for decapita-tion in the medieval Kamakura passed deep into the cervical vertebral column from the right rear, and yet came to a full stop within the bone after severing the spinal cord and the right vertebral artery, putting him to death.

A Japanese tradition in the feudal Edo period was that the anterior skin of the neck should be left intact at the time of decapitation. The present material, added to the decapitated skulls des-cribed previously by MORIMOTO (1987), reveals that the halfway-cut method of decapitation for man was adopted not only in the more recent Edo era, but also in the early medieval Muromachi or Nambokucho period of Japan. BROTHWELL (1981) mentioned that decapitation usually

resulted in cleanly divided cervical vertebrae, as seen in Iron Age specimens from Sutton Walls. This apparently was not the traditional method of decapitation in Japan of ancient times. It should be, therefore, noted that the traditional Japanese method of decapitation was distinguish-able from the ancient European manner, by a halfway-cut from the right rear.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to express their thanks to Mr. Norikata MATSUO of the Board of Educa-tion of Kamakura City and Mr. Hiroshi HARA of the director of the excavations of Yuigahama Medieval Cemetery for material and helpful suggestions. 抄 録 中世 鎌 倉 出土 の打 ち首,追 加1例 森 本 岩 太 郎 ・平 田 和 明 か つ てMORIMOTO(1987)が 報 告 した 南 北 朝 期 に お け る打 ち首2例 の追 加 と して,1991年 に 鎌 倉 市 比 由 ケ浜 中世 集 団墓 地 か ら出 土 し た 同 時 代 の 壮 年 期 男 性 頭 蓋1例 を 提示 す る.こ の 頭 蓋 は第1∼4頸 椎 ・舌 骨 と と もに 墓 地 に 埋 め られ て い た.他 の 骨 格 部 分 は な い.頭 蓋 に は6個 の 刀 創 が 見 ら れ る.う ち3個 は 死 の 直 前 に受 けた もの で,前 頭 鱗 右 側 を 左 前 方 か ら 右 後 方 に 斜 め に走 って 板 間 層 に 達 す る長 さ45mmの 刀 創(a),右 眼 窩 外 側 縁 の骨 を そ ぎ落 と した 刀 創(b), 右 頭 頂 骨 を 前 後 方 向 に走 って 頭 蓋 冠 表 面 と接 線 方 向 に浅 く頭 蓋 腔 に達 した刀 創(c)で あ るが,こ れ ら は 浅 く,直 接 死 因 で は な さ そ うで あ る.残 り の3個 は, 後 頭 骨 右 下 項 線 を そ ぎ落 と した 刀 創(d),右 下 顎 枝 後 縁 に ほ ぼ水 平 に切 り込 ん だ2個 の 刀 創(e,f)で あ る.後 頭 骨 の刀 創(d)は 打 ち 首 の 時 か 死 後 の も の か は分 か らな いが,右 下 顎 枝 の 刀 創(e,f)は,後 述 す る軸 椎 の刀 創(i,h)と そ れ ぞ れ 一 致 す る. い っぽ う頸 椎 に は右 後 方 か ら鋭 く切 り込 ん だ ほ ぼ 水 平 に走 る5回 分6個 の 刀 創 が 認 め ら れ る.上 方 か ら順 に,環 椎 の椎 弓下 縁 を か す め て(9),軸 椎 歯 突 起 の後 部 に達 して 止 ま る刀 創(h),軸 椎 の 椎 弓 上 部

358 I. MORIMOTO and K. HIRATA と右 上 関 節 突 起 後 部 を切 り軸 椎 体 に 達 して 止 ま る刀 創(i),軸 椎 の棘 突 起 を 右 後 下 方 か ら切 っ て 椎 弓 内 で 止 ま る刀 創(j),第3頸 椎 の 棘 突 起 ・右 下 関 節 突 起 ・椎 弓 ・椎 体 を 右後 下 方 か ら切 って 左 椎 弓 根 で 止 ま る刀 創(k).第4頸 椎 の 棘 突 起 ・右 下 関 節 突 起 ・椎 体 下 部 を 切 り離 して 椎 体 の 左1/4部 で 止 ま る 刀 創 (D,で あ る. 上 述 の よ うに 環 椎 の 刀 創(g)お よ び 軸 椎 の 刀 創 (h)は 右下 顎 枝 後 縁 の 刀 創(f)と,ま た軸 椎 の 刀 創 (j)は 右 下 顎 枝 後 縁 の 刀 創(e)と,そ れ ぞ れ 一 致 す る.舌 骨 に 刀創 は見 られ な か っ た. 打 ち首 され た 時 の 創 傷 は環 椎 ・軸 椎 ・右 下 顎 枝 に 残 る 刀創(g+h+f)か,ま た は 軸 椎 の 刀 創(i)の い ず れ か と推 測 され,こ れ は頸 髄 ・右 椎 骨 動 脈 を 完 全 に横 切 し,致 命 的 で あ る.ま た 軸 椎 ・右 下 顎 枝 の 刀 創(j+e)お よ び第3・4頸 椎 の刀 創(k)・(1)は 死 後 頭 部 を 切 り離 した際 に加 え られ た も の と思 わ れ る.本 例 は たぶ ん手 負 い の 武 士 が 名 を 重 ん じ首 を 打 た れ た もの で あ ろ う. 江 戸 時 代 に は 「打 ち首 は頸 の 前 皮 一 枚 残 して 切 る の が常 法』 と言 わ れ た が,古 い 日本 の 半 切 り に よ る 打 ち 首 の伝 統 の起 源 が 南 北 朝 期 ま で さ か の ぼ り得 る こ とを示 す好 例 と して,先 の2例 と と も に本 例 は 注 目 され る. References

BROTHWELL, D.R., 1981: Digging up Bones, 3rd ed. British Museum (Natural History)/Cornell Univ.

Press, New York, pp. 120-121.

KAWAGOE, T., 1965: Edo Period Excavated. Maruzen, Tokyo, pp. 82-85. (In Japanese)

〔河 越 逸 行,1965:堀 り 出 さ れ た 江 戸 時 代.丸 善,東 京,pp.82-85.〕

MORIMOTO, I., 1981: Examples of human skeletal remains from Kanto District, Japan. Monthly

Archaeological Journal, 197: 13-18. (In Japanese)

〔森 本 岩 太 郎,1981:古 人 骨 研 究 の 事 例,(1>関 東. 月 刊 考 古 学 ジ ャ ー ナ ル,197:13-18.〕

MORIM0T0, I., 1987: Note on the technique of capitation in medieval Japan. J. Anthrop. Soc.

Nippon, 95: 477-486.

森 本 岩 太 郎 聖 マ リァ ンナ医科大学第2解 剖学教室

〒216 川崎市宮前 区菅生2-16-1

Iwataro MORIMOTO Department of Anatomy

St. Marianna University School of Medicine 2-16-1 Sugao, Miyamae-ku, Kawasaki 216

Japan