Gendered Objects Gendering Bodies:

Self-Defense Tools and Their Role in

Constructing Perceptions of the Potential of

the Female Body

Rafael MuniaCity University of New York Abstract

Perceptions of young women in Japan are examined in relation to female self-defense. Several women in Japan were surveyed, with some chosen for interviews. It seemed that self-defense was often connected not to learning assault-prevention techniques but to purchasing self-defense tools. This finding opens two avenues for discussion. First, the marketization of personal safety is explored, as is the genderization of these tools and the subsumption of women’s safety into a logic of consumption. Second, the shift from viewing the body as a weapon to viewing the object as one, which projects various forms of subjectification onto women, is discussed. These include the outsourcing of women’s agency to an external object. It is concluded that this outsourcing often results in the reinforcement of tropes of fragility and the neutralization of resignifications of the female body that emerges from practitioners who focus on the body as the instrument of self-defense.

K

Keeyy wwoorrddss: female self-defense, body, subjectivity, patriarchal discourse, immaterial capitalism

The first contact with the informants took place via a short survey with 38 questions, covering topics ranging from the amount of previous experience with self-defense classes to previous experiences with cases of sexual harassment and a series of hypothetical scenarios in which respondents were asked about their imagined reactions to situations. From the initial pool of 188 respondents, 85 agreed to complete further in-depth interviews so that some of the trends observed during the survey could be explored in more depth and other topics could be discussed based on the personal experiences of each informant. The fact that some informants agreed to respond to an anonymous survey in which their answers could not be personally identified yet hesitated or refused to participate in interviews in which the author would be able to personally identify their answers is, in itself, a relevant finding.

The in-depth interviews were conducted in many stages, with the author reaching out periodically to the informants with further questions and points for discussion. Such an approach was adopted to keep the interviews open to the knowledge acquired during the interview process itself. Answers given by an informant sometimes inspired a series of new questions that could then be asked to past informants. Also, by constantly revisiting the topics with the informants, such temporality allowed the author to observe how the respondents’ attitudes changed during the project.

A condition established throughout the entire process of conducting the survey and interviews was the complete anonymity of the participants. Therefore, throughout the text, the informants shall be represented by numbers randomly assigned to them without any accompanying personal information that could expose their identities. We understand this may make it impossible to conduct an analysis of the individual characteristics of each informant, but we chose to

M

Meetthhooddoollooggiiccaall SSttrraatteeggiieess aanndd R

Reesseeaarrcchh BBaacckkggrroouunndd

The examination found in this paper is part of a larger project about perceptions and experiences of female self-defense among women in Japan. What began as a research project meant to inform a proposal for female self-defense classes aimed at exchange students progressed to a deeper exploration of notions of the body and power among women in Japan as the author began to notice distinct trends among respondents. Based on an initial survey, the author then proceeded to conduct further in-depth interviews with some of the respondents to examine their conceptualization of gender, power, and the body as well as the bi-directional impact that self-defense receives from and presents to these conceptualizations. Furthermore, this work is focused on providing an exploration of a specific topic within the larger data obtained through this research project, namely the object-subject relationship that emerged from the relationships between the informants and self-defense tools and the kind of subjectivity that was produced through this relationship.

In this paper, the reader will find first a debate on how objects have been conceptualized in anthropology, especially with the rise of new materialism and object-oriented ontology. The reader will also find a discussion on the intersection of gender and ideology as apparatuses of the subjectification of the female and male bodies. Then, two examples of how the process of gendering bodies takes place are presented, first through examples of female self-defense and sexual education classes, then by examining examples of self-defense tools and the discursive apparatus that justifies their use. From the comparison between these two processes of subjectification, a conclusion can be drawn and comments on the actor-network theory and post-human project can be offered.

The first contact with the informants took place via a short survey with 38 questions, covering topics ranging from the amount of previous experience with self-defense classes to previous experiences with cases of sexual harassment and a series of hypothetical scenarios in which respondents were asked about their imagined reactions to situations. From the initial pool of 188 respondents, 85 agreed to complete further in-depth interviews so that some of the trends observed during the survey could be explored in more depth and other topics could be discussed based on the personal experiences of each informant. The fact that some informants agreed to respond to an anonymous survey in which their answers could not be personally identified yet hesitated or refused to participate in interviews in which the author would be able to personally identify their answers is, in itself, a relevant finding.

The in-depth interviews were conducted in many stages, with the author reaching out periodically to the informants with further questions and points for discussion. Such an approach was adopted to keep the interviews open to the knowledge acquired during the interview process itself. Answers given by an informant sometimes inspired a series of new questions that could then be asked to past informants. Also, by constantly revisiting the topics with the informants, such temporality allowed the author to observe how the respondents’ attitudes changed during the project.

A condition established throughout the entire process of conducting the survey and interviews was the complete anonymity of the participants. Therefore, throughout the text, the informants shall be represented by numbers randomly assigned to them without any accompanying personal information that could expose their identities. We understand this may make it impossible to conduct an analysis of the individual characteristics of each informant, but we chose to

informants who already had experience with self-defense classes (or the martial arts, which were consistently confused with self-defense by the informants) as well as with those who were seeing what takes place in such classes for the first time. It is also important to mention that this strategy was adopted at a late stage of the interviews, allowing for the collection of responses before respondents were exposed to the materials and then after they had been shared so that the author could analyze whether the introduction of these materials caused any transformation in the responses or reactions of the informants.

M

Maatteerriiaalliissm

m aass C

Crriittiiqquuee ooff AAnntthhrrooppoocceennttrriissm

m,, FFeem

miinniissm

m

aass C

Crriittiiqquuee ooff AAnnddrroocceennttrriissm

m

In the field of anthropology, the critique of anthropocentrism has been gaining momentum with every passing year. Many approaches abound, as they highlight various focal points of critique. Ideas such as the actor-network theory (Latour 2007) and Meshworks (Ingold 2015) have helped to establish a “flat” ontology (Harman 2018) that does not privilege human agency over non-human objects. Object-oriented ontology (Harman 2018) has provided a new framework for metaphysics that argues for the independent existence of objects regardless of human perception. It is further argued that their ontology is not exhausted by their relationships, whether with humans or non-human objects. This preoccupation with extending anthropological inquiry beyond the limitations of the human world has led to interesting ethnographical work, such as that of Hull (2012) and its examination of the role of paper in the execution of Pakistani governmental functions or that of Parikka (2015) and its examination of the material implications of immaterial production prioritize their anonymity, especially considering that the aim of this

paper is to show how these processes are occurring in a very similar way despite the heterogeneity of the informants.

The use of the expression in Japan rather than Japanese is employed to signal that the informants are not necessarily of Japanese nationality but are people living in Japan and, thus, constituents of the population subject to the gendering process taking place through Japanese institutions. While this paper does not specify the nationalities of informants individually for reasons of privacy, half of the total pool of informants consisted of those who described themselves as Japanese, while the other half was composed of non-Japanese nationals. While the prevalence of divisions between Japanese and non-Japanese within the anthropology of Japan has been thoroughly critiqued (see Hansen and Ertl 2015), in this work, an attempt is made to account for a Japan inhabited by subjects other than Japanese nationals. The ages of the informants varied from 20 to 46; their educational backgrounds varied as well, with the group including some who had only finished high school, some who had attended vocational schools, some with a university education, and some with graduate-school experience. Regardless of the variations in their backgrounds, the narratives we present throughout this paper presented surprisingly similar answers regarding how women view their own bodies and the male body as well as how they have reacted or imagine they would react to violence against women.

As part of the methodological strategies adopted during the in-depth interviews, videos featuring various styles of female self-defense were shown to some informants and discussed with them as they shared their reactions. Opinion pieces written by female self-defense instructors were also shared with the informants to assess their reactions to the material. This was done with both the

informants who already had experience with self-defense classes (or the martial arts, which were consistently confused with self-defense by the informants) as well as with those who were seeing what takes place in such classes for the first time. It is also important to mention that this strategy was adopted at a late stage of the interviews, allowing for the collection of responses before respondents were exposed to the materials and then after they had been shared so that the author could analyze whether the introduction of these materials caused any transformation in the responses or reactions of the informants.

M

Maatteerriiaalliissm

m aass C

Crriittiiqquuee ooff AAnntthhrrooppoocceennttrriissm

m,, FFeem

miinniissm

m

aass C

Crriittiiqquuee ooff AAnnddrroocceennttrriissm

m

In the field of anthropology, the critique of anthropocentrism has been gaining momentum with every passing year. Many approaches abound, as they highlight various focal points of critique. Ideas such as the actor-network theory (Latour 2007) and Meshworks (Ingold 2015) have helped to establish a “flat” ontology (Harman 2018) that does not privilege human agency over non-human objects. Object-oriented ontology (Harman 2018) has provided a new framework for metaphysics that argues for the independent existence of objects regardless of human perception. It is further argued that their ontology is not exhausted by their relationships, whether with humans or non-human objects. This preoccupation with extending anthropological inquiry beyond the limitations of the human world has led to interesting ethnographical work, such as that of Hull (2012) and its examination of the role of paper in the execution of Pakistani governmental functions or that of Parikka (2015) and its examination of the material implications of immaterial production

In the heyday of existentialism, Simone de Beauvoir exposed how women, or female subjects, were always defined in relation to men, prompting her to call women the second sex (Beauvoir 2011). Beauvoir, in her seminal work, takes us on a historical tour of how philosophers have constantly defined women as lacking in something or as “incomplete men.” She, of course, rejects such a definition, arguing that, as her existentialist philosophy held, there was no such thing as a women’s essence, and that women were no exception to the maxim existence precedes essence, which means women were capable of defining themselves based on that choices they made in life. This conceptualization of women as the “Other,” according to Beauvoir, is central to the establishment of patriarchy and is the basis of the myth of male superiority. These ideas are furthered by the work of Irigaray (1985) on the phallocentrism of language and discourse, in which she shows how the language used in philosophy has always been “masculine,” thus forcing women to narrate their experiences through the language of men.

The conceptualization of women as being defined through men and in relation to them and as a lacking or incomplete subject informed the ethnographical work of Martin (2017), in which she demonstrated how the scientific discourse about female eggs and

much interesting work has been conducted on the multiplicity and fluidity of expressions of gender that transcend “binarisms,” such as male and female (see Preciado 2018), the informants’ responses demonstrate that the ideations of female and male as categories are still relevant in the way that they describe notions of what a female and a male body can do. It creates different categories of power, autonomy, and responsibility. Therefore, when we speak about the ideological production of gender, we are, by no means, disregarding the arguments made against the binary division of gender that exists in patriarchal societies. Instead, we are discussing how our informants have used these binary categories to navigate their experiences and establish themselves as subjects.

and the era of digitalization.

In the same vein as Parikka, we encounter other noteworthy attempts to de-center the human, such as those of “Geontology” (Povinelli 2016) and “New Materialism” (Dolphijn and Tuin 2012). These approaches vary significantly from the ideas presented by Marx in his conceptualization of commodity fetishism, which, as Žižek (2018) critiques, positions the object-commodity as a form of deceit in which the subject sees in the object that which is not present in it. Žižek, remaining within the scope of ideology-imbued objects, agrees with the premise of Marx, that is, that objects are fetishized by humans. However, in his seminal work on ideology (Žižek 2008), he goes further in saying that it is not simply the case that there is an inherent reality in an object that is then falsified and transformed into something more. Rather, objects reproduce ideologies exactly because what we see in them, out of the myriad possibilities we could see, is conditioned by the existing ideology. Žižek, in this sense, follows Harman’s logic that an object’s ontology is not determined by its relationship with a human subject and that it possesses characteristics that are independent of such relationships. In other words, an object possesses numerous characteristics, and we can only apprehend some of them; furthermore, what we tend to apprehend from them usually stems from our current ideology.

This specific insight is of central relevance to the arguments that will be presented in this work. Therefore, it is impossible to separate the debate about objects and materiality from the debate about ideology, specifically regarding the process of gendering through objects, or how male and female subjects are produced by ideology.1

1 Here, it is important to note a distinction regarding the ideological

In the heyday of existentialism, Simone de Beauvoir exposed how women, or female subjects, were always defined in relation to men, prompting her to call women the second sex (Beauvoir 2011). Beauvoir, in her seminal work, takes us on a historical tour of how philosophers have constantly defined women as lacking in something or as “incomplete men.” She, of course, rejects such a definition, arguing that, as her existentialist philosophy held, there was no such thing as a women’s essence, and that women were no exception to the maxim existence precedes essence, which means women were capable of defining themselves based on that choices they made in life. This conceptualization of women as the “Other,” according to Beauvoir, is central to the establishment of patriarchy and is the basis of the myth of male superiority. These ideas are furthered by the work of Irigaray (1985) on the phallocentrism of language and discourse, in which she shows how the language used in philosophy has always been “masculine,” thus forcing women to narrate their experiences through the language of men.

The conceptualization of women as being defined through men and in relation to them and as a lacking or incomplete subject informed the ethnographical work of Martin (2017), in which she demonstrated how the scientific discourse about female eggs and

much interesting work has been conducted on the multiplicity and fluidity of expressions of gender that transcend “binarisms,” such as male and female (see Preciado 2018), the informants’ responses demonstrate that the ideations of female and male as categories are still relevant in the way that they describe notions of what a female and a male body can do. It creates different categories of power, autonomy, and responsibility. Therefore, when we speak about the ideological production of gender, we are, by no means, disregarding the arguments made against the binary division of gender that exists in patriarchal societies. Instead, we are discussing how our informants have used these binary categories to navigate their experiences and establish themselves as subjects.

literature (Irigaray 1985), and the discourse of philosophy (Beauvoir 2011) but in most of our cultural production through the damsel in distress trope (Sarkeesian and Adams 2018), a narrative device in which a passive female character is stripped of all agency and must rely on a heroic male to come to her rescue.

An example of how this ideological apparatus is materialized in everyday life was provided by one of our informants. She sent us a picture of a sign in the Singaporean MRT station that asked, “What should I do if I am molested?” The answers provided on the sign are “call for help,” “alert the staff,” and “take note of the appearance and attire of the culprit.” In the survey that was the basis of this research project, when asked, “If attacked by a man, would you instinctively look for another man for help?,” 78% of the informants answered positively, with 63% adding they did not think they would be capable of defending themselves. As Hollander (2004) accurately points out, females who have been socialized to adhere to the conventional feminine role have been taught to be passive, dependent, emotional, helpless, inadequate, ladylike, and incapable of protecting themselves. They have been encouraged to limit their mobility in public spaces and to rely for protection on men to avoid becoming victimized. In addition, some of the informants shared experiences in school in which the police taught them what to do if they were attacked: scream for help and report the incident to the police. The construction of women as damsel-in-distress subjects comes not only from the media but is also reproduced by the police, school, family, and all the other institutions Althusser considered to be “Ideological State Apparatuses” (2008).

male sperm was imbued with ideological discourses on masculinity

and femininity, lending a biological veneer to gender-based stereotypes. Her work aptly shows how the scientific literature she examined describes how, by extolling the female cycle as a productive enterprise, menstruation must necessarily be viewed as a failure. Meanwhile, the same texts that regard menstruation as a failed production cast the production of sperm as a successful enterprise in which hundreds of millions of sperm are produced each day. According to her, the texts produce the impression that females are not only unproductive but also wasteful. The irony becomes evident when one realizes that, while a woman producing an average of five hundred eggs in her lifetime is described as wasteful in biological texts, the fact that a man produces an average of over two trillion sperm in his lifetime is not viewed the same way.

Martin continues by showing how women’s eggs are viewed as “passive” and men’s sperm are considered “active,” reproducing gendered stereotypes of femininity and masculinity. The only description of sperm as weak and timid that Martin can find comes from a Woody Allen movie in which Allen plays an apprehensive sperm inside a man’s testicles who are scared of the man’s approaching orgasm. He is reluctant to launch himself into the darkness, afraid of contraceptive devices or of winding up on the ceiling if the man is masturbating. Meanwhile, in medical texts, the recurrent depiction is that of the egg as a “damsel in distress,” shielded only by her sacred garments; the sperm is cast as a heroic warrior coming to the rescue.

What these philosophical and anthropological works demonstrate to us is how the ideology of modernity subjectifies women as always lacking something: the strength, energy, courage, and agency that men are imagined to possess. Their work has demonstrated how these pervasive ideas can be found not only in medical texts (Martin 2017),

literature (Irigaray 1985), and the discourse of philosophy (Beauvoir 2011) but in most of our cultural production through the damsel in distress trope (Sarkeesian and Adams 2018), a narrative device in which a passive female character is stripped of all agency and must rely on a heroic male to come to her rescue.

An example of how this ideological apparatus is materialized in everyday life was provided by one of our informants. She sent us a picture of a sign in the Singaporean MRT station that asked, “What should I do if I am molested?” The answers provided on the sign are “call for help,” “alert the staff,” and “take note of the appearance and attire of the culprit.” In the survey that was the basis of this research project, when asked, “If attacked by a man, would you instinctively look for another man for help?,” 78% of the informants answered positively, with 63% adding they did not think they would be capable of defending themselves. As Hollander (2004) accurately points out, females who have been socialized to adhere to the conventional feminine role have been taught to be passive, dependent, emotional, helpless, inadequate, ladylike, and incapable of protecting themselves. They have been encouraged to limit their mobility in public spaces and to rely for protection on men to avoid becoming victimized. In addition, some of the informants shared experiences in school in which the police taught them what to do if they were attacked: scream for help and report the incident to the police. The construction of women as damsel-in-distress subjects comes not only from the media but is also reproduced by the police, school, family, and all the other institutions Althusser considered to be “Ideological State Apparatuses” (2008).

include attacking the assailant, and often emphasized the lack of forcefulness required. This is not difficult to understand, since a common theme that appeared among Japanese informants was the idea that violence was not feminine. Many informants recalled being afraid that, if they hit a boy at school, their parents would severely scold them for doing something that was considered improper for a girl. Informant #1 confessed to not being interested in self-defense because she considered fighting a form of violence that was usually better suited to boys than girls. Informant #2 was interested in taking self-defense classes but was stopped by her mother, who considered it too violent, as she was a girl. Finally, informant #3 recounted her experience of defending herself at school against a boy who was assaulting her with racist remarks only to be berated by her mother for not acting like a girl should. Therefore, it is not shocking that the classes geared towards women attempt to sell their techniques as non-violent, excluding any form of attack and emphasizing how gentle the techniques are.

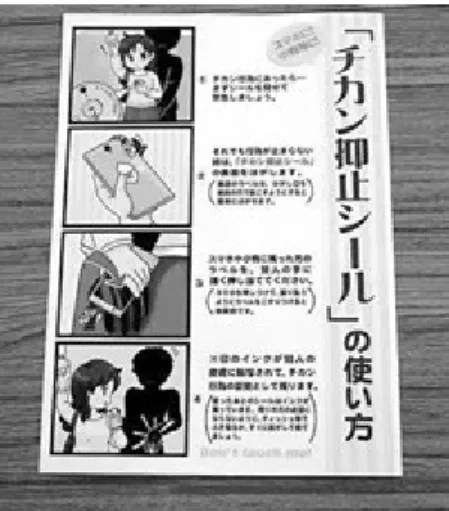

Figure 1. Poster showing how women can “mark” gropers with a seal. Source: Picture provided by an informant.

FFeem

maallee SSeellff--D

Deeffeennssee aanndd tthhee PPrroodduuccttiioonn ooff G

Geennddeerreedd

SSuubbjjeeccttss

Given the situation described so far, female self-defense emerges as an attempt to reimagine female agency. Female self-defense established itself as a series of techniques designed with women in mind and with the intention of providing women with the tools to defend themselves from an assault, usually from male counterparts. When we state that these techniques were designed “with women in mind,” this engenders a series of assumptions about what a woman is physically capable of doing, and each response to this question generates different results in the context of the type of self-defense course presented. We quickly realized that many of the self-defense classes some of our informants took part in or watched on TV or online reinforced the view of the female as lacking something. Perhaps the most radical example of this was the existence of classes offered in Japan with the theme of “women’s and children’s self-defense.” These classes placed women and children in the same group, since they were both seen as incomplete people lacking the strength and skill that a male adult is assumed to have. In doing so, the class’s organizers infantilized women quite literally, beginning with the premise that a woman’s body is not capable of defending itself and thus requires a set of self-defense techniques that would better suit a child.

There were also abundant examples of self-defense classes geared toward females in Japan that were often shown on variety shows, were produced to be shown online, and that took place in schools and workplaces, all of which constitute a subtler version of the same process. These were classes in which the instructors went out of their way to present the techniques in a way that was not violent, did not

include attacking the assailant, and often emphasized the lack of forcefulness required. This is not difficult to understand, since a common theme that appeared among Japanese informants was the idea that violence was not feminine. Many informants recalled being afraid that, if they hit a boy at school, their parents would severely scold them for doing something that was considered improper for a girl. Informant #1 confessed to not being interested in self-defense because she considered fighting a form of violence that was usually better suited to boys than girls. Informant #2 was interested in taking self-defense classes but was stopped by her mother, who considered it too violent, as she was a girl. Finally, informant #3 recounted her experience of defending herself at school against a boy who was assaulting her with racist remarks only to be berated by her mother for not acting like a girl should. Therefore, it is not shocking that the classes geared towards women attempt to sell their techniques as non-violent, excluding any form of attack and emphasizing how gentle the techniques are.

Figure 1. Poster showing how women can “mark” gropers with a seal. Source: Picture provided by an informant.

laughed at the videos while commenting, “So, do they expect the attacker not to chase after us!?” Others expressed similar reactions, albeit in a more puzzled tone, commenting, “But what happens if he runs after us?” One informant, #5, while watching a scene in which a woman who had been grabbed by both wrists was instructed to twist them inwards with her thumbs up and then run away as the man stood still watching her run, commented in an annoyed tone, “Really!? If it were me in that position, I would just kick his balls!”

What these replies show, besides how ideas of womanhood and femininity inform self-defense practices, is that women should not be understood as passive subjects who simply follow the ideology imposed on them by the patriarchal myth of female fragility and passiveness. Many of the women mocked these classes and rejected being the subjectification imposed by such gender norms. However, this does not negate the role that such self-defense classes play in producing a specific kind of subjectivity among women and reinforcing a discourse of proper femininity as “non-violent,” especially when such classes are the ones that are most likely to be seen on TV, to take place at their school or workplace, and to appear in search results when one searches for “female self-defense” in Japanese online. For many of the informants, such classes became their first impression of what female self-defense classes were like, and, given their content, it usually became their only one, since many of them cited “lack of application/usefulness in real life” among the reasons that they did not have any interest in taking female self-defense classes.

There is yet another type of female self-defense lesson that many informants felt was unhelpful or counterproductive. If the examples given before were of classes that reinforced the myth of female fragility and of “proper womanhood” centered in notions of The techniques presented in these courses are usually limited to

techniques such as twisting one’s own wrist to release oneself from an assailant’s grip or crouching while raising one’s arms to escape from a hug from the back. After executing such techniques, the women are then instructed to run away. While such techniques are taught in many other self-defense classes, they are usually followed by a swift attack to one of the assailant’s weak spots to debilitate him, opening a space for the person being attacked to run away. However, such a follow-up move is absent from these classes, as the “violence” of the attack is replaced by running away.

As discussed in the “methodology” section, part of our study consisted of showing some of these videos to our informants to inquire about their reactions, both to those who had never taken self-defense classes as well as to those who had. Some informants

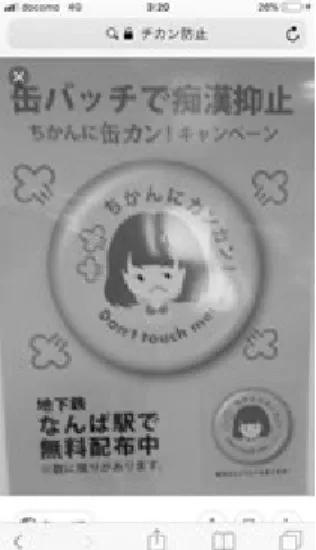

Figure 2. Button distributed for free at subway stations with a message to gropers: “Don’t touch me.” Source: Picture provided by an informant.

laughed at the videos while commenting, “So, do they expect the attacker not to chase after us!?” Others expressed similar reactions, albeit in a more puzzled tone, commenting, “But what happens if he runs after us?” One informant, #5, while watching a scene in which a woman who had been grabbed by both wrists was instructed to twist them inwards with her thumbs up and then run away as the man stood still watching her run, commented in an annoyed tone, “Really!? If it were me in that position, I would just kick his balls!”

What these replies show, besides how ideas of womanhood and femininity inform self-defense practices, is that women should not be understood as passive subjects who simply follow the ideology imposed on them by the patriarchal myth of female fragility and passiveness. Many of the women mocked these classes and rejected being the subjectification imposed by such gender norms. However, this does not negate the role that such self-defense classes play in producing a specific kind of subjectivity among women and reinforcing a discourse of proper femininity as “non-violent,” especially when such classes are the ones that are most likely to be seen on TV, to take place at their school or workplace, and to appear in search results when one searches for “female self-defense” in Japanese online. For many of the informants, such classes became their first impression of what female self-defense classes were like, and, given their content, it usually became their only one, since many of them cited “lack of application/usefulness in real life” among the reasons that they did not have any interest in taking female self-defense classes.

There is yet another type of female self-defense lesson that many informants felt was unhelpful or counterproductive. If the examples given before were of classes that reinforced the myth of female fragility and of “proper womanhood” centered in notions of

weak to fight, other classes reinforce myths about men as being too strong to be defeated by women.

On the other side of the spectrum, however, there are well-researched and thoughtful classes that emphasize female empowerment and confidence in the potential one’s own body has to protect itself, focusing on techniques that are practical for the situations most often faced by women. It is important to emphasize these things, especially in the context of the female self-defense classes found most often in the Japanese media and public settings. While those classes consider “geared towards women” equivalent to teaching techniques that “even a woman could learn” and portraying an image of women as “incomplete men” lacking the same power and skills as a man, these classes, on the other hand, consider “geared towards women’ equivalent to teaching techniques that can be used to respond to the types of situations women are likely to face. Thus, women are considered equal to men in terms of their potential to learn how to defend themselves but different from men in terms of the situations they are likely to face.

Another important aspect of these classes is that they cover not only physical techniques but also how women are socialized to believe they are fragile and powerless and the psychological aspects that discourage women from being assertive, among other elements like verbal defense, boundary-setting, etc. Both feminist self-defense (Hollander 2004), as well as holistic self-defense (Wild Inside Wellness 2019), emphasize how physical self-defense must be accompanied by the production of a new female subject, one that includes a new understanding of the potential of the female body and that does not see the female body as lacking the potential of the male body.

While the literature on feminist self-defense adequately points out the importance of creating a new women’s subjectivity that helplessness, weakness, and “non-violence,” the other type includes

classes that reinforced the myth of male supremacy. In such classes, led by male instructors, the techniques are enacted by two males,2 and the emphasis is placed on techniques that look flashy and choreographed. They involve high-kicks, throws, complex punch combinations, and other techniques that would require both a lot of energy and many years of training for proper execution, which stands in direct opposition to some of the main premises of female self-defense: that the techniques be easy to perform, remember, and learn. Thus, such lessons serve merely as a demonstration of masculine excellence to a female audience, and the reactions of the informants tend to be the opposite of what one would expect from a class meant to teach them that they are capable of defending themselves. Instead, they often appear intimidated, and the gender-gap myth is, once again, reified.

“The guys make it look easy, but I don’t think I could do that in an attack situation, it is just not realistic,” said informant #5. “I think, generally, guys are stronger than girls, so in a real situation, I don’t think I could do these things. I would probably just scream for help or try to run away,” said informant #6. “Maybe if I trained really hard, I could take a guy the same size as me. But I don’t think I would be able to fight back if it were a big guy,” commented informant #7. Thus, while some classes reinforce myths about women as being too

2 Some of these lessons are performed in video format for an imagined audience,

and, although they are called “female self-defense,” they are only enacted by male instructors. Others feature female students during the lesson, yet one can see that much of the time is occupied by male instructors demonstrating techniques to an impressed audience, while little time is devoted to allowing the women to practice these techniques, which are performed under the micro-management of the instructors, raising doubts about the generation of autonomy during the process.

weak to fight, other classes reinforce myths about men as being too strong to be defeated by women.

On the other side of the spectrum, however, there are well-researched and thoughtful classes that emphasize female empowerment and confidence in the potential one’s own body has to protect itself, focusing on techniques that are practical for the situations most often faced by women. It is important to emphasize these things, especially in the context of the female self-defense classes found most often in the Japanese media and public settings. While those classes consider “geared towards women” equivalent to teaching techniques that “even a woman could learn” and portraying an image of women as “incomplete men” lacking the same power and skills as a man, these classes, on the other hand, consider “geared towards women’ equivalent to teaching techniques that can be used to respond to the types of situations women are likely to face. Thus, women are considered equal to men in terms of their potential to learn how to defend themselves but different from men in terms of the situations they are likely to face.

Another important aspect of these classes is that they cover not only physical techniques but also how women are socialized to believe they are fragile and powerless and the psychological aspects that discourage women from being assertive, among other elements like verbal defense, boundary-setting, etc. Both feminist self-defense (Hollander 2004), as well as holistic self-defense (Wild Inside Wellness 2019), emphasize how physical self-defense must be accompanied by the production of a new female subject, one that includes a new understanding of the potential of the female body and that does not see the female body as lacking the potential of the male body.

While the literature on feminist self-defense adequately points out the importance of creating a new women’s subjectivity that

attention in this account, however. A central part of a female self-defense lessons is the study of the fragile points of a male attacker’s body. Rather than emphasize brute strength, female self-defense classes teach women about the areas of a male’s body that can be exploited to cause maximum pain while requiring little force. Although various instructors might provide varying numbers of weak points, some common ones emerge: the eyes, nose, throat, solar plexus, testicles, and knees. These are areas of the body that are the most fragile and thus the most susceptible to pain, even if not they are hit with significant force. Thus, it is essential to the experience of self-defense to not only reimagine the female body as strong and powerful but also the male body as vulnerable.

G

Geennddeerriinngg PPoow

weerr aanndd V

Vuullnneerraabbiilliittyy

However, it is in this respect that the responses from our informants were the most intriguing and unexpected. As mentioned briefly before, despite learning about the existence of weak points in a male’s body, most of the informants seemed to remain firm in their belief that it would be difficult for them, as women, to injure a male body. “When I was in school, the police came to our school to give self-defense lessons. I’ve also taken self-defense lessons outside of school, but I’m a small girl, so I’m not sure if I could fight back if it were a big guy,” said informant #8, who, after several experiences with self-defense lessons, opted to buy pepper spray for fear of not being able to defend herself, given her belief in the disparity in strength between both genders. “Personally, I think that the self-defense classes are not very helpful because it will cause the attacker to become angry if you resist. Since women are physically weaker than men, confronting the threat is not a good idea” said demystifies the notions of fragility, helplessness, passiveness, and

weakness associated with the female body (see Madden and Sokol 1997; Hollander 2004; Rouse and Slutsky 2014; Arif 2015; O’Loughlin 2019), too little importance seems to be assigned to the equally important task of demystifying the myth of male invulnerability, powerfulness, and superiority to which many of the informants still fiercely subscribe. It was common to hear from informants who, despite feeling empowered by taking self-defense lessons, were still not confident in their capacity to protect themselves, arguing that their techniques would only be efficient if the man in question were not too big or strong. In other words, while they no longer believed that women could not fight or be strong, they maintained that men were stronger. Thus, the myth of women as “incomplete” remained. Could they be strong? Yes, but not as strong as a man.

Hollander (2004), in her work on feminist self-defense practices, provides an excellent summary of the literature discussing women’s experiences with their bodies. On the one hand, she points to the literature that shows how women report experiencing their bodies as inadequate, shameful, fragile, and contaminating. On the other hand, she also points to the literature of feminist theorists that, while calling much-needed attention to men’s violence against women, often conflates women’s experiences with violence with women’s vulnerability to violence. Thus, since women are often victimized, explains Hollander, many have assumed that women are innately and necessarily vulnerable to such victimization. She then argues that, through the practice of feminist self-defense, as women begin to feel that their bodies can protect them rather than make them vulnerable, the value and respect that they give to their bodies increases as well.

attention in this account, however. A central part of a female self-defense lessons is the study of the fragile points of a male attacker’s body. Rather than emphasize brute strength, female self-defense classes teach women about the areas of a male’s body that can be exploited to cause maximum pain while requiring little force. Although various instructors might provide varying numbers of weak points, some common ones emerge: the eyes, nose, throat, solar plexus, testicles, and knees. These are areas of the body that are the most fragile and thus the most susceptible to pain, even if not they are hit with significant force. Thus, it is essential to the experience of self-defense to not only reimagine the female body as strong and powerful but also the male body as vulnerable.

G

Geennddeerriinngg PPoow

weerr aanndd V

Vuullnneerraabbiilliittyy

However, it is in this respect that the responses from our informants were the most intriguing and unexpected. As mentioned briefly before, despite learning about the existence of weak points in a male’s body, most of the informants seemed to remain firm in their belief that it would be difficult for them, as women, to injure a male body. “When I was in school, the police came to our school to give self-defense lessons. I’ve also taken self-defense lessons outside of school, but I’m a small girl, so I’m not sure if I could fight back if it were a big guy,” said informant #8, who, after several experiences with self-defense lessons, opted to buy pepper spray for fear of not being able to defend herself, given her belief in the disparity in strength between both genders. “Personally, I think that the self-defense classes are not very helpful because it will cause the attacker to become angry if you resist. Since women are physically weaker than men, confronting the threat is not a good idea” said

issue. At first, she shared with us the following: “Neither my parents nor the school taught me how to defend myself, and, when it comes to the issue of sex or anything related to it, like the words ‘penis’ or ‘adult video’, most parents here avoid talking about such issues with their children.” Later, she also shared the following: “I remember that one day one of my classmates, a girl, hit a boy’s penis with her leg, and the boy cried because of the pain.” This confusion between the penis and testicles was also detected in some of the other answers from the survey. An exemplary case was the following answer to the question “How or where have you learned about the groin being a man’s weakness?”: “It is the nearest area to the dick, the weakest spot of the male. If you hit the groin, you will hopefully hit his dick (which will cause him a lot of pain).”

What we can learn from this is that, not only do some female self-defense classes do little to demystify the male body as invulnerable, with some even reinforcing this myth, but the lack of proper sexual education further mystifies the male body, providing fertile ground for the perpetuation of the idea that the male body is inherently strong and cannot be defeated.

To further emphasize this point, it is helpful to examine the narratives from the informants who did receive proper sexual education in school and were thus able to learn that the male body is not invulnerable, but, in fact, possesses some very fragile areas that, when hit in a self-defense situation, could guarantee the debilitation of a male attacker and allow more than enough time for a woman to escape the situation. While far fewer by comparison, the experiences of the girls who possessed such knowledge were very different. Some of their responses included informant #11’s assertion that “Maybe I learned about guy’s weaknesses when I took a health and physical education class in elementary school. In that class, we had lessons informant #9, echoing a preoccupation that many other informants

had—the fear that reacting to an assault would cause the attacker to become angrier and worsen the situation. In fact, during the survey, many of the answers to the question, “In a situation in which you felt attacked, how would you defend yourself?” included some variation of complying and doing what the attacker asked to calm him down. Some of the answers included “I don’t think I would do anything to provoke the attacker,” “the best way out is not to react,” “do what they ask to make them calm down,” and “I wouldn’t react and would do whatever I were told to end it sooner,” among others.

In all of these situations, the male body is still imagined as impenetrable, invulnerable, and invincible, and many of the female respondents felt that the only thing that attacking a male body could accomplish would be to anger the male attacker and make the situation worse. The situation appeared more drastic in some of the in-depth interviews, with respondents providing answers like the following: “I’m scared that if I kicked the guy’s groin, and the kick were not strong enough, it would make him furious and more violent,” “I know that the groin is a guy’s weakest spot, but what if a guy were able to train it or he could somehow withstand the pain?,” “I guess that, even though I know about it, I wouldn’t do it, because what if he hits me back later?,” and “Actually, I don’t really think I could defeat any male by hitting him in the crotch. Is that even true?”

These remarks point out something else that is also worth discussing when we are dealing with the topic of demystifying the male body. The issue here concerns knowledge of the male body and its anatomy. In both the survey and the in-depth interviews, another issue became apparent—the lack of knowledge many of the informants had about the male anatomy.

issue. At first, she shared with us the following: “Neither my parents nor the school taught me how to defend myself, and, when it comes to the issue of sex or anything related to it, like the words ‘penis’ or ‘adult video’, most parents here avoid talking about such issues with their children.” Later, she also shared the following: “I remember that one day one of my classmates, a girl, hit a boy’s penis with her leg, and the boy cried because of the pain.” This confusion between the penis and testicles was also detected in some of the other answers from the survey. An exemplary case was the following answer to the question “How or where have you learned about the groin being a man’s weakness?”: “It is the nearest area to the dick, the weakest spot of the male. If you hit the groin, you will hopefully hit his dick (which will cause him a lot of pain).”

What we can learn from this is that, not only do some female self-defense classes do little to demystify the male body as invulnerable, with some even reinforcing this myth, but the lack of proper sexual education further mystifies the male body, providing fertile ground for the perpetuation of the idea that the male body is inherently strong and cannot be defeated.

To further emphasize this point, it is helpful to examine the narratives from the informants who did receive proper sexual education in school and were thus able to learn that the male body is not invulnerable, but, in fact, possesses some very fragile areas that, when hit in a self-defense situation, could guarantee the debilitation of a male attacker and allow more than enough time for a woman to escape the situation. While far fewer by comparison, the experiences of the girls who possessed such knowledge were very different. Some of their responses included informant #11’s assertion that “Maybe I learned about guy’s weaknesses when I took a health and physical education class in elementary school. In that class, we had lessons

the male body has weaknesses, that it can be fragile, and that women can easily cause tremendous pain to it, the informants no longer felt weak. Therefore, not only, as Hollander (2004) shows us, does learning self-defense techniques enable women to experience their bodies as being capable of hurting someone and protecting them while demystifying harmful views of their own bodies, the provision of thorough knowledge of the male body to women also enables them to demystify harmful views of the male body.

Some of our research results also highlighted the fact that, even when their schools not only failed to teach female students about their potential to protect themselves and the vulnerability of the male body, some of our informants were still able to acquire such knowledge through experimentation, which led to similar results. A salient example came from informant #14: “So, actually, in elementary school, I’m not sure whether it began out of curiosity, but I used to kick boys in the shins and realized I could be very powerful by doing that. I stopped doing that in the 5th grade, but I found out that it was one of their weak spots. So, I wasn’t afraid of fighting with boys. I think I stopped in the 5th grade because a teacher scolded me for the deed! I’d made several boys cry with it, so … It does make sense for us to learn about the weaknesses of men to gain more confidence.”

The philosopher Judith Butler was one of the key figures in demonstrating the importance of vulnerability in the way politics and societies are constructed (Butler 2004). Butler argues that vulnerability is a shared experience and that our political and social arrangements should always be based on the notion that we are all vulnerable. However, as sociologist Lisa Wade has cleverly noted, while female vulnerability is always assumed, male vulnerability is often hidden, disguised, or negated. In one of her texts, Wade begins about sex education, and I got to know how fragile the two balls are”

or informant #12’s that “I certainly feel more comfortable and relaxed knowing that I can defeat men by attacking their weak points, even though I’m much smaller.”

All the informants who had learned this information in school reported feeling empowered, comfortable, and safe, as well as the absence of a feeling of inferiority in relation to their male counterparts, including in the area of physical strength.3 Perhaps the best and most detailed example of this feeling came from informant #13: “In my biology class in high school, we learned about the human body, and the teacher taught us about a boy’s testicles and that they were the weakest part of his body; the teacher told us (female students) to attack that spot in case of an attack. She told us that ‘It’s a fragile part. It’s also the only organ that is vulnerable but lies outside the body. Hitting that spot will cause the attacker a lot of pain, and he won’t have enough strength to continue attacking you.’ It did make me feel very comfortable. We learned it in a class that included boys, and we no longer felt weak, especially when my teacher said to the boys, ‘Are you listening, my boys? You had better behave yourselves.’”

Here, once more, we see how, by publicizing the knowledge that

3 While self-defense classes tend to point out many vulnerable areas on a male

body, it is important to note that, when talking about the knowledge that enabled them to feel empowered, more comfortable, safe, and without a feeling of inferiority towards men, the testicles appeared especially important to women. This is related to the fact that, while the eyes, nose, and so on are vulnerabilities shared by both the female and the male body, the testicles generate an image of a vulnerability attached specifically to males. In addition, many informants shared how they noticed boys and men being extra careful and protective of their groin area in a variety of situations, something that was not observed about other sources of vulnerability.

the male body has weaknesses, that it can be fragile, and that women can easily cause tremendous pain to it, the informants no longer felt weak. Therefore, not only, as Hollander (2004) shows us, does learning self-defense techniques enable women to experience their bodies as being capable of hurting someone and protecting them while demystifying harmful views of their own bodies, the provision of thorough knowledge of the male body to women also enables them to demystify harmful views of the male body.

Some of our research results also highlighted the fact that, even when their schools not only failed to teach female students about their potential to protect themselves and the vulnerability of the male body, some of our informants were still able to acquire such knowledge through experimentation, which led to similar results. A salient example came from informant #14: “So, actually, in elementary school, I’m not sure whether it began out of curiosity, but I used to kick boys in the shins and realized I could be very powerful by doing that. I stopped doing that in the 5th grade, but I found out that it was one of their weak spots. So, I wasn’t afraid of fighting with boys. I think I stopped in the 5th grade because a teacher scolded me for the deed! I’d made several boys cry with it, so … It does make sense for us to learn about the weaknesses of men to gain more confidence.”

The philosopher Judith Butler was one of the key figures in demonstrating the importance of vulnerability in the way politics and societies are constructed (Butler 2004). Butler argues that vulnerability is a shared experience and that our political and social arrangements should always be based on the notion that we are all vulnerable. However, as sociologist Lisa Wade has cleverly noted, while female vulnerability is always assumed, male vulnerability is often hidden, disguised, or negated. In one of her texts, Wade begins

him to want to hurt you more. Schorn points to statistical evidence (Tark and Kleck 2014) that shows that the opposite is true and that doing so significantly reduces a woman’s chances of being hurt. The third myth she addresses, namely, “Groin kicks aren’t really that devastating; I’ve seen lots of guys get hit in the balls and it hardly fazed them,” has also affected many of our informants, who thought their strength might not be adequate to injure a man. However, as Schorn points out, this response is disseminated almost universally by men, who, she mockingly notes, “rarely volunteer to demonstrate their own iron balls in a real kicking situation, but confidently assert that men in general can shrug off all kinds of damage to the groin,” to which she adds, “I’ve seen two-year-olds take down grown men via the groin, and toddlers don’t even have any training. I do. I like my odds.”

Yet, as many of our informants have had negative experiences with self-defense classes that reinforced myths about female fragility, as well as with a lack of sexual education classes in school that would help them question myths about male invulnerability, many of them have opted to seek other solutions to address their feeling of powerlessness and fear of being victimized.

O

Obbjjeeccttss SSuubbjjeeccttiiffyyiinngg BBooddiieess

As we mentioned before, informant #8, despite having taken self-defense classes in and out of school, still felt too weak to fight a male attacker and resorted instead to purchasing pepper spray. She bought the pepper spray because, as she told us, she considered her small body inadequate for confronting a larger, male body. The pepper spray, crucially, did not change her perception of herself, as she continued to view her own body as weak; thus, she resorted to by asking the question “Why don’t more men hit each other below

the belt?” (Wade 2015). In the text, Wade is puzzled by the lack of logic she perceives in the fact that, even in a no-holds-barred fight, men still hesitate to hit each other in the groin, which prompts Wade to ask, “If you dislike each other enough to want them to get hurt, why not do the worst?”

Wade also brings to the fore some of the answers she got from men, who often call it a low blow or a cheap shot, evoking a sort of honor code of manhood. However, Wade provides a different answer. According to her, such a tacit pact takes place “because it serves to protect men’s egos as well as men’s balls,” since, as she argues, “it would add up to less time looking powerful and more time looking pitiful. And it would send a clear message that men’s bodies are vulnerable.” Wade continues: “not hitting below the belt, then, protects the idea that men’s bodies are fighting machines. It protects masculinity, the very idea that men are big and strong, pain- and impact-resistant, impenetrable like an edifice. So not hitting below the belt doesn’t just protect individual men from pain, it protects our ideas about masculinity. When a man hits below the belt, he is revealing to everyone present that masculinity is a fiction. So, men generally agree to pretend that the balls just aren’t there. The effect is that we tend to forget just how vulnerable men are to the right attack and continue to think of women as naturally more fragile.”

In another important text, author and self-defense instructor Susan Schorn (2014) takes time to address some of the myths that are told to women to hide, or prevent them from acquiring accurate knowledge about, male vulnerability, which could be shared. The first and second myths she addresses are some of the same ones shared by many of our informants, namely, the assumption that, if you kick the testicles of a male attacker, it will only make him angry and cause

him to want to hurt you more. Schorn points to statistical evidence (Tark and Kleck 2014) that shows that the opposite is true and that doing so significantly reduces a woman’s chances of being hurt. The third myth she addresses, namely, “Groin kicks aren’t really that devastating; I’ve seen lots of guys get hit in the balls and it hardly fazed them,” has also affected many of our informants, who thought their strength might not be adequate to injure a man. However, as Schorn points out, this response is disseminated almost universally by men, who, she mockingly notes, “rarely volunteer to demonstrate their own iron balls in a real kicking situation, but confidently assert that men in general can shrug off all kinds of damage to the groin,” to which she adds, “I’ve seen two-year-olds take down grown men via the groin, and toddlers don’t even have any training. I do. I like my odds.”

Yet, as many of our informants have had negative experiences with self-defense classes that reinforced myths about female fragility, as well as with a lack of sexual education classes in school that would help them question myths about male invulnerability, many of them have opted to seek other solutions to address their feeling of powerlessness and fear of being victimized.

O

Obbjjeeccttss SSuubbjjeeccttiiffyyiinngg BBooddiieess

As we mentioned before, informant #8, despite having taken self-defense classes in and out of school, still felt too weak to fight a male attacker and resorted instead to purchasing pepper spray. She bought the pepper spray because, as she told us, she considered her small body inadequate for confronting a larger, male body. The pepper spray, crucially, did not change her perception of herself, as she continued to view her own body as weak; thus, she resorted to

pepper sprays and stun guns posts daily self-defense tips on social networks. Among such tips, we encounter advice like “Stop the sexy selfies, while it’s the norm these days, it could be compromising your personal safety with internet creeps,” “Use unique photos for your dating profile. It’s too easy for someone to do a reverse image search and your social media profiles be displayed,” “Do a background check on any new roommates, love interests, and anyone you are letting into your personal space,” “Don’t get wasted when you travel, just don’t. No explanation needed,” “Never wear your earbuds when you’re running alone. Never. Ever. Ever,” “If you must shop at night, use the online purchase and pick up option,” and “Keep a ball cap in your car and put it on when you are driving. Looking like a man reduces your chances of being a target.” The common element among all these hints is that none of them place any importance on producing an autonomous female subject. Most of them ask women to stop doing things that may want to do, such as listening to music while running, sharing their pictures online, drinking, or simply looking like a woman. They disable women, and they deauthorize them from existing in public space.

There is something ironic about a company selling self-defense tools while promoting the narrative that women’s self-defense means being afraid at all times, limiting one’s activities for fear of something bad happening, and always imagining oneself as a victim. This can be contrasted with the results of Hollander’s (2004) research on how the empowerment of women who took feminist self-defense classes and resignified their bodies has led to women feeling more comfortable and confident in public spaces, feeling comfortable taking up more space, talking more assertively, and being unafraid to exist in public. It is also worth mentioning that part of the website’s content is also related to the constant maintenance required by pepper sprays and relying on an external device for protection.

The idea of external objects compensating for the limitations of the human body is something that has already been hinted at by Donna Haraway (1998) and has provoked substantial debates within the field of post-humanism and trans-humanism (Kim 2017). Such authors have re-considered nature and humanity as we approach a technological epoch in which the previously perceived limitations of the body can be addressed by prosthetic enhancements that merge humans and objects into hybrid forms of life.

However, we contend that, in the case of self-defense tools, what we see is precisely the opposite. While their apparent and self-styled purpose resembles the trans-humanist conceptualization, since a self-defense tool is supposed to compensate for the limitations of the female body, giving her the power that her own body lacks and allowing her to defend herself, the results we obtained indicate that such self-defense tools are counter-productive to attaining all the elements necessary for transcending the current myth of female vulnerability and male invulnerability we have discussed so far.

To begin, we can further discuss the pepper spray mentioned by our informant. As we can see, acquiring the pepper spray acts as a substitute for viewing one’s own body as capable of hurting others and protecting itself (Hollander 2004). It also helps to maintain the illusion that a small, female body cannot hurt a large, male body. The pepper spray, thus, acts not as a tool of empowerment but as an ideological apparatus that relegates gender inequalities to the background with a promise of not having to challenge our views of female and male bodies. This also becomes clear when we analyze the types of narratives that are promoted by the companies that produce these tools.

pepper sprays and stun guns posts daily self-defense tips on social networks. Among such tips, we encounter advice like “Stop the sexy selfies, while it’s the norm these days, it could be compromising your personal safety with internet creeps,” “Use unique photos for your dating profile. It’s too easy for someone to do a reverse image search and your social media profiles be displayed,” “Do a background check on any new roommates, love interests, and anyone you are letting into your personal space,” “Don’t get wasted when you travel, just don’t. No explanation needed,” “Never wear your earbuds when you’re running alone. Never. Ever. Ever,” “If you must shop at night, use the online purchase and pick up option,” and “Keep a ball cap in your car and put it on when you are driving. Looking like a man reduces your chances of being a target.” The common element among all these hints is that none of them place any importance on producing an autonomous female subject. Most of them ask women to stop doing things that may want to do, such as listening to music while running, sharing their pictures online, drinking, or simply looking like a woman. They disable women, and they deauthorize them from existing in public space.

There is something ironic about a company selling self-defense tools while promoting the narrative that women’s self-defense means being afraid at all times, limiting one’s activities for fear of something bad happening, and always imagining oneself as a victim. This can be contrasted with the results of Hollander’s (2004) research on how the empowerment of women who took feminist self-defense classes and resignified their bodies has led to women feeling more comfortable and confident in public spaces, feeling comfortable taking up more space, talking more assertively, and being unafraid to exist in public. It is also worth mentioning that part of the website’s content is also related to the constant maintenance required by pepper sprays and

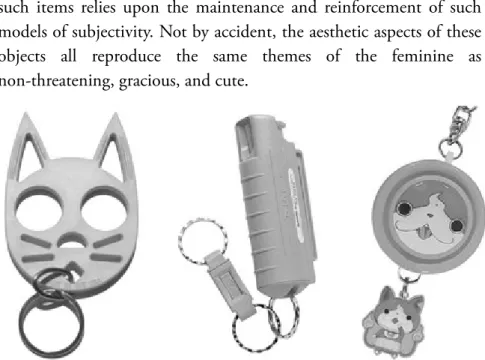

kubotans, and cat rings, among others, this was the only one that completely bypassed any confrontation with the assailant.

While a pepper spray requires the user to use the item to attack the assailant, an alarm’s only chance for effectiveness relies on at least one of two premises being realized: either it must frighten/embarrass the attacker, who must then run away, or it must attract the attention of police officers or other people in the area who are willing to come to the rescue of the alarm’s owner. It negates any form of attack on the assailant. Its effectiveness is also negated if an assault happens in an area where no one can hear it, if no one who hears it bothers to risk their own safety to help its owner, if the attacker proceeds with the attack despite the alarm, or if, in the heat of the moment, the user fails to pull the pin in time.

Informant #15 told us about her experience with such an alarm. According to her, all the students at her school received a portable alarm from the staff. However, as she recounted the experience, she admitted the following: “Honestly, I think the alarm wouldn’t work to let others know something was happening because so many students ended up setting them off by accident. So, it was hard to discern whether the students were using it intentionally or if it was just another false alarm.” Informant #5 also shared her opinion of portable alarms, stating that, “When I saw them being sold, I noticed that most of them did not even come with instructions on how to use them.”

While the alarm proved to be a commonly owned item by our informants, it was generally given to them by someone else, usually a boyfriend or a parent. Many who owned such alarms reported disbelief in the efficacy of the item itself, with many ending up leaving them at home, putting them inside their bags, or simply losing track of them altogether. Paradoxically, some of the informants stun guns to ensure that they are always charged, kept away from heat,

and kept from being used on windy days, amongst other inconveniences that may render such tools literally useless when their users must rely on them for their protection. If Butler (2004) reminds us that all life is precarious, then we should also be reminded that all objects are precarious.

When we discuss the gendering of bodies through ideas of vulnerability, it also becomes relevant to discuss the vulnerability of objects, particularly that of self-defense tools. Objects themselves are vulnerable. They require maintenance, they can break, their functionality may be hindered by the weather, they may have an expiration date, they depend on the skill of the user to function properly, and so on. Some other objects, like alarms, are intersubjective items that do not only require the maintenance of their batteries and the know-how of the user so they can function properly when they are needed, they also require the attacker to be either afraid of or ashamed by the sound of the alarm or the solidarity of a passer-by who notices it and feels like intervening on behalf of the woman being attacked. Thus, the alarm, as an object, constitutes part of a network of actors (Latour 2007) who must all act appropriately to produce the desired result.

While many of our informants reported having relied on pepper sprays because they did not believe that they were capable of defeating a man in an altercation, the most commonly used self-defense item that informants in Japan reported having used was, by far, the portable alarm. These alarms are small and portable and can be attached to a keychain, cellphone, or backpack, and they emit a loud noise when a pin is removed from them. There is much that can be said about this type of object. First, when we compared them to other self-defense items, such as pepper sprays, stun guns,