Evolution, Income-dependent Relative Concerns, and Modern

Fertility Transition

Junji Kageyama∗ Revised on April 30, 2013

Abstract

The aim of this study is to examine how the income-dependency of relative concerns affects the general pattern of modernization. Incorporating this type of preferences into an economic model, this study provides an explanation for the relationship between modern economic growth and modern fertility transition.

JEL: A12, B41, D01, J13, O11

∗Department of Economics, Meikai University, Akemi 1, Urayasu, Chiba 279-8550, Japan (e-mail: kage- jun@meikai.ac.jp). I thank Joshua R. Goldstein for valuable discussions and suggestions on the relationship between fertility and social interaction, and Michael Kuhn for providing me helpful comments. Any remaining errors are of course my own. This study is financially supported by Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Exploratory Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (No. 23653055).

1 Introduction

An increasing number of studies in economics search for biological bases of preferences. The bi- ological basis of time preferences, for example, has been examined by Rogers (1994), Sozou and Seymour (2003), Robson and Samuelson (2009), Kageyama (2011, 2012b), and Chowdhry (2011). The origin of relative concerns, likewise, has been investigated by Cole, Mailath and Postlewaite (1992, 1995), Robson (1996, 2001), Samuelson (2004), N¨oldeke and Samuelson (2005), Rayo and Becker (2007), De Fraja (2009), and Kageyama (2012a).

Yet, the aim of these studies is often limited to providing explanations for the preferences that have already been discovered in empirical and experimental studies, such as the age-trajectory of time preference, hyperbolic discounting, and the income-happiness paradox (Easterlin, 1974). An attempt to make novel predictions on preferences purely from biological theories is still rare.

The contribution of such an attempt is not only to fulfill theoretical interests. More importantly, particularly in social science, its significance lies in its application to provide explanations for economic and social phenomena.

Along this line, this study focuses on the finding in Kageyama (2012a) that, for low income levels, people care about absolute, but not relative, standing such as the absolute level of consumption, but, when income reaches a certain level, people start to care about both absolute and relative standing, suggesting that the degree of concerns for relative standing is at least partially increasing in income.

The rationale for this finding comes from behavioral ecology studies that, in pre-modern hu- man population, social standing affects lifetime reproductive success through reproduction, which depends on both fertility and the survival of offspring, rather than through one’s own survival. In- corporating this effect into a biological model, Kageyama (2012a) shows that, as resources increase, reproduction and, thus, relative standing become more decisive to lifetime reproductive success, leading to the spread of preferences that induce greater concerns for relative standing when income increases.

Introducing this result into an economic model, the present study examines how the income- dependency of relative concerns affects reproductive behavior and economic performance. This study is also considered an extension of Leibenstein (1975), Tournemaine (2008), and Tournemaine

and Tsoukis (2008) that incorporate status concerns in examining fertility and economic growth. In particular, Tournemaine (2008) and Tournemaine and Tsoukis (2008) show that a greater concern for status results in having fewer but higher quality children. In this respect, the novelty of the present analysis is to include the income dependency in status concerns.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The next section provides a theoretical model, and Section 3 discusses its implications. The results show that, once the economy escapes from the Malthusian trap, this type of preferences induces endogenous economic growth and the fertility transition characterized by the initial increase in fertility and the reduction in fertility thereafter. Section 4 concludes.

2 Model

I assume the following properties to hold. First, individuals are homogenous. Second, individuals live for two periods, the first period we refer to as childhood, and the second period, adulthood. Third, individuals make all decisions in adulthood. Forth, at period t, income, yt, is allocated to consumption, ct, the number of children, mt, and educational input, st. Thus, the budget constraint is given by

yt≥ ct+ (ψ + σst)mt (1)

where ψ and σ respectively denote the cost of raising a child and the price of educational input, both of which are time-invariant. Fifth, income depends on human capital, ht, and human capital depends on educational input in the previous period. Specifically, they are respectively given by yt= ωht and ht= sβt−1 where ω is wage rate and β < 1 is an efficiency parameter.

Sixth, individuals are endowed with income-dependent relative preferences, meaning that in- dividuals are concerned with their own relative standing and that the degree of such concerns is increasing in income. Seventh, parents care about the well-being of their children as well as their own. However, as parents cannot directly observe their children’s utility, I assume that parents perceive children’s utility through empathy. Empathy helps the parents understand the feelings of children but through the parents’ own scale of utility.1

1The argument “we sympathize even with the dead (Smith, 1759)” is a good illustration of how we use our own

This has two implications. First, parents use the same income-dependent relative preferences to measure their children’s well-being. Second, since parents obtain their own utility from consumption in adulthood, they care about their children’s consumption in their adulthood. To capture this latter aspect, I assume that parents are concerned with children’s growth that signals the children’s consumption in adulthood and measure children’s growth with educational output.

By putting these conditions together and by following Weber’s law that suggests that we measure utility in logarithmic form, the utility function of the adult at period t can be written as

Ut= γ ln(ct− ˆct) + (1 − γ) ln [

mt (

sβt −sˆβt )]

(2)

where γ is the importance of one’s own consumption relative to reproduction, and ˆct and sˆβt are the reference levels for comparison.

Here, ˆct and sˆβt depend on their social averages, ¯ct and s¯βt, such that ˆct = ztc¯t and sˆβt = zts¯βt where ztdenotes the degree of concerns for the social averages. As ztincreases, the individual cares more about the social averages, and if zt= 0, the individual cares only about absolute levels. Note that, given that zmax is the upper limit of zt, I assume for technical simplicity that the condition zmax<1 − β holds. To capture the income-dependency of relative concerns, I further assume that zt= z(yt) and, for any z(yt) ≤ zmax, z′(yt) > 0 hold.2

2.1 Intratemporal equilibrium

With these specifications, the Lagrangian for the adult at period t becomes

L(ct, mt, st, λt) = γ log(ct− ˆct) + (1 − γ) log [

mt

(

sβt −sˆβt )]

+λt[yt− ct− (ψ + σst)mt] . (3)

where λtis the Lagrangian multiplier. Note that ytis not controllable for the adult at period t as it is determined by educational input in the previous period. Subsequently, the first-order conditions

scale of utility to measure the feelings of others.

2I assume that parents have positional concerns on the education, but not on the number, of children, considering that positional concern on the number of children is significantly less, if not non-existent, as compared to those on education. Namely, parents don’t gain utility from having more children but from higher-educated children. However, I acknowledge the possibility that a greater number of children may result in enhancing actual social status in some cultures.

are given by

∂L

∂c = γ 1

c− ˆc− λ = 0, (4)

∂L

∂m = (1 − γ) 1

m − λ (ψ + σs) = 0, (5)

∂L

∂s = (1 − γ)

βsβ−1

sβ− ˆsβ − λσm = 0, (6)

and

∂L

∂λ = y − c − (ψ + σs)m = 0 (7)

where period subscripts are suppressed whenever possible.

Next, assume that the population is sufficiently large that the changes in c and s at the individual level have a negligible impact on the social averages. Then, by applying the condition that adults are homogeneous and thus choose the same levels of c and s, ¯c and ¯sβ are respectively given by c and sβ. As a result, consumption, fertility, and education become

c= γ

γ+ [1 − z(y, α)](1 − γ)y, (8)

m= [1 − z(y, α) − β](1 − γ) γ+ [1 − z(y, α)](1 − γ)

y

ψ, (9)

and

s= ψ σ

β

1 − z(y, α) − β. (10)

With these results, we can examine how c, s, and m respond to a change in y. By differentiating c, s, and m with respect to y, we have

∂c

∂y =

γ

γ+ [1 − z(y)] (1 − γ) +

γ(1 − γ)z′(y)

{γ + [1 − z(y)] (1 − γ)}2y >0, (11)

∂s

∂y = ψ σ

βz′(y)

[1 − z(y) − β]2 >0, (12)

and

∂m

∂y =

[1 − z(y) − β] (1 − γ) γ+ [1 − z(y)] (1 − γ)

1 ψ−

[γ + β(1 − γ)] (1 − γ)z′(y) {γ + [1 − z(y)] (1 − γ)}2

y

ψ. (13)

Equations (11), (12), and (13) show that the impact of income on the resource allocation consists of two effects: the income effect, i.e., the direct effect of income, and the relative concern effect, i.e., the change in concerns for relative standing. Consumption increases with income because both effects are positive, and education increases with income because the relative concern effect is

positive while the income effect is nil. By contrast, the impact of income on fertility is indeterminate. Equation (13) shows that the relative concern effect is negative while the income effect is positive. To further examine this point, consider the case, which I call the benchmark scenario, where z(y) is linear in y such that z(y) = ηy for z(y) ≤ zmax. In this case, equation (13) becomes

∂m

∂y =

1 − γ

[γ + (1 − ηy)(1 − γ)]2 1

ψ[(1 − ηy)

2− γη2y2− β] (14)

for z(y) ≤ zmax. Here, the term in the final bracket, (1−ηy)2−γη2y2−β, is positive if y is sufficiently small, and is negative if y is sufficiently large. The income effect dominates the relative concern effect when income is low, and vice versa when income is high. As a result, in the present model, the relationships between education and income, and fertility and income can be summarized as:

Proposition 1. Given the positive effect of income on relative concerns, education increases with income. Moreover, under the benchmark scenario, fertility increases with income when income is sufficiently low, and decreases with income when income is sufficiently high.

2.2 Intertemporal equilibria

At the same time, income depends on reproductive decision. Reproductive decision intertemporally affects income through the level of human capital. This intertemporal effect is summarized in the dynamics of human capital. By inserting equation (10) and yt= ωht into ht+1= sβt, ht+1becomes

ht+1= j(ht) =[ ψ σ

β 1 − z(ωht) − β

]β

(15)

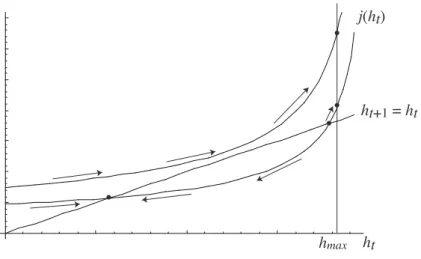

for z(ωht) ≤ zmax. Equation (15) shows that j(ht) is positive at z(ωht) = 0 and increasing in ht. Furthermore, under the benchmark scenario where z(yt) = ηyt, j(ht) is convex in ht. This leads to the following proposition.

Proposition 2. Under the benchmark scenario:

(1) If j(0) and j′(ht) are sufficiently small, there exist at most two steady states that satisfy ht+1 = ht where the one with the lower ht is stable and the one with the higher ht is unstable. Besides, there exists a steady state, either stable or unstable depending on parameter values, that

satisfies ht+1= j(hmax) where hmax= zmaxηω , corresponding to the corner solution at zmax.

(2) If j(0) and j′(ht) are sufficiently large, there exists no steady state that satisfies ht+1= ht, but exists a stable steady state that satisfies ht+1= j(hmax).

Figure 1 presents these two cases. The convex curve at the bottom represents the first case, and the one at the top represents the second case. In the second case, human capital continues to grow until it reaches its upper limit where ht+1= j(hmax) holds.

Place Figure 1 around here

3 Implications

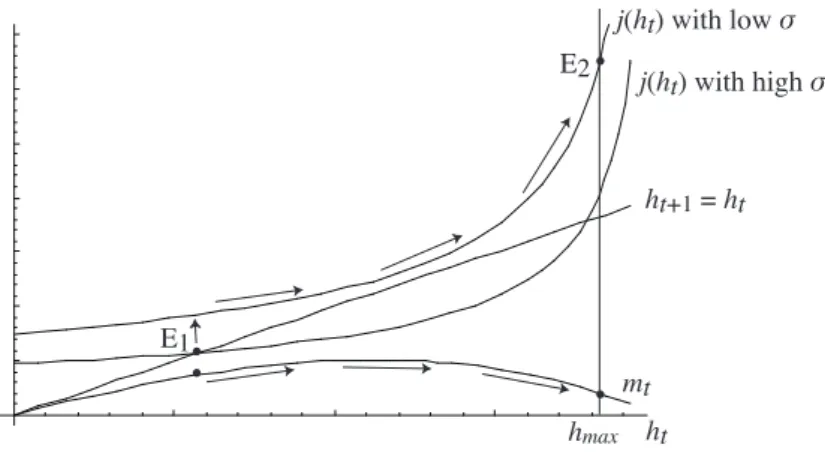

The present analysis yields the following implications. First, it provides an explanation for the big-push and the subsequent economic growth in modern history. To see this, suppose that the economy is originally trapped at its stable steady state presented by the point E1 in Figure 2, and that educational efficiency eventually increases. This lowers the price of education, σ, and shifts j(ht) upwards. If the shift is sufficiently large, j(ht) no longer intersects with ht+1 = ht, and, as shown in Figure 2, human capital and income jump to the new levels and grow steadily until the economy reaches the new steady state E2.

Place Figure 2 around here

In this growth process, fertility increases initially but decreases thereafter. The concave curve at the bottom of Figure 2 presents this dynamics. This is consistent with the empirical evidence on the modern fertility transition. As presented by Dyson and Murphy (1985), most countries, both developing and developed, had undergone a rise in fertility in the initial phase of the modern economic growth before they experienced a reduction in fertility.

Possible reasons for this transitional movement in fertility have previously been provided by

Galor and Weil (2000) and Tournemaine and Tsoukis (2008). Galor and Weil (2000) show that technological progress that increases the return to education can explain this phenomenon. Tourne- maine and Tsoukis (2008), on the other hand, argue that an exogenous shock in status concerns is the cause of the fertility transition. Relating to this point, the present study suggests that the change in status concerns is indeed endogenous.3

Second, the present study shows that the time cost of raising children is not a prerequisite for the quality-quantity trade-off, pointing to a possibility that fertility may decline even when the opportunity cost of raising children remains constant.4

This result is consistent with the pattern of fertility decline in Japan in the third quarter of the 20th century where marital fertility declined dramatically while being a housewife remained a common practice. In this period, although women’s participation in the labor force did not rise, the fertility rate declined from 3.65 to 1.91 mainly due to the change in marital fertility (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research of Japan, 2008, Table 4.15).5 This indicates that the cause of the fertility decline during this period is not the increase in working opportunities for women. Instead, recalling that Japan experienced a rapid economic growth in this period, we can attribute it to the relative concern effect.

4 Concluding Remarks

This study incorporates the finding in Kageyama (2012a) that the degree of relative concerns is income-dependent, and shows that, once the economy escapes from the Malthusian trap, this type of preferences induces endogenous economic growth and the fertility transition characterized by the initial increase in fertility and a reduction thereafter. By incorporating biologically-predicted preferences into economics, it provides an explanation for the general pattern of modernization.

3Applying these results, the present analysis also provides an explanation for the transition from a Malthusian Regime, through a Post-Malthusian Regime, to a Modern Growth Regime discussed in Galor and Weil (2000).

4See Jones, Schoonbroodt and Tertilt (2008) for the importance of the time cost for generating the quality-quantity trade-off.

5Women’s labor force participation rate was 48.6% in 1950, 50.9% in 1960, 50.9% in 1970, and 46.1% in 1975 (Statistics Bureau of Japan, 2011b). Focusing on married women, the rate declined from 51% in 1962 to 45% in 1975 (Statistics Bureau of Japan, 2011a).

These results suggest that limiting research to a narrow and safe definition of preferences would incur costs. The income-dependency of relative concerns, being taken as an example, potentially accounts for various economic and social phenomena. A novel prediction on preferences inserts a unique perspective into the study of sociality.

References

Chowdhry, Bhagwan (2011) ‘Possibility of dying as a unified explanation of why we discount the future, get weaker with age, and display risk-aversion.’ Economic Inquiry 49, 1098–1103

Cole, Harold L., George J. Mailath, and Andrew Postlewaite (1992) ‘Social norms, savings behavior, and growth.’ Journal of Political Economy 100, 1092–1125

(1995) ‘Incorporating concern for relative wealth into economic models.’ Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review 19, 12–21

De Fraja, Gianni (2009) ‘The origin of utility: Sexual selection and conspicuous consumption.’ Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 72, 51–69

Dyson, Tim, and Mike Murphy (1985) ‘The onset of fertility transition.’ Population and Develop- ment Review 11, 399–440

Easterlin, Richard A. (1974) ‘Does economic growth improve the human lot?’ In Nations and Households in Economic Growth: Essays in Honour of Moses Abramovitz, ed. Paul A. David and Melvin W. Reder (New York: Academic Press) pp. 88–125.

Galor, Oded, and David N. Weil (2000) ‘Population, technology, and growth: From malthusian stagnation to the demographic transition and beyond.’ American Economic Review 90(4), 806– 828

Jones, Larry E., Alice Schoonbroodt, and Michele Tertilt (2008) ‘Fertility theories: can they explain the negative fertility-income relationship?’ NBER Working Paper

Kageyama, Junji (2011) ‘The intertemporal allocation of consumption, time preference, and life- history strategies.’ Journal of Bioeconomics 13, 79–95

(2012a) ‘Child survival, the evolution of income-dependent relative concerns, and happiness.’ Meikai University Discussion Paper

(2012b) ‘Why are children impatient? evolutionary selection of preferences.’ Meikai University Discussion Paper

Leibenstein, Harvey (1975) ‘The economic theory of fertility decline.’ Quarterly Journal of Eco- nomics 89, 1–31

National Institute of Population and Social Security Research of Japan (2008) Population Statistics of Japan (Tokyo, Japan)

N¨oldeke, Georg, and Larry Samuelson (2005) ‘Information-based relative consumption effects: Cor- rection.’ Econometrica 73, 1383–1387

Rayo, Luis, and Gary S. Becker (2007) ‘Evolutionary efficiency and happiness.’ Journal of Political Economy 115(2), 302–336

Robson, Arthur J. (1996) ‘The evolution of attitudes to risk: Lottery tickets and relative wealth.’ Games and Economic Behavior 14, 190–207

(2001) ‘The biological basis of economic behavior.’ Journal of Economic Literature 39, 11–33

Robson, Arthur J., and Larry Samuelson (2009) ‘The evolution of time preference with aggregate uncertainty.’ American Economic Review

Rogers, Alan R. (1994) ‘Evolution of time preference by natural selection.’ American Economic Review84(3), 460–481

Samuelson, Larry (2004) ‘Information-based relative consumption effects.’ Econometrica 72, 93–118

Smith, Adam (1759) The theory of moral sentiments (London)

Sozou, Peter D., and Robert M. Seymour (2003) ‘Augmented discounting: interaction between ageing and time-preference behaviour.’ Proceedings of the Royal Society B 270, 1047–1053

Statistics Bureau of Japan (2011a) Annual Report on the Labor Force Survey of Japan

(2011b) Population Census of Japan

Tournemaine, Frederic (2008) ‘Social aspirations and choice of fertility: why can status motive reduce per-capita growth?’ Journal of Population Economics 21, 49–66

Tournemaine, Frederic, and Christopher Tsoukis (2008) ‘Status, fertility, growth and the great transition.’ MPRA Paper

ht hmax

•

•

•• ht+1 = ht j(ht)

Figure 1: Steady states and dynamic paths.

ht+1 = ht

ht hmax

mt E1

E2

j(ht) with high σ j(ht) with low σ

••

•

•

Figure 2: Modern economic growth and modern fertility transition.