Frame Phonosemantics:

A Frame-Semantic Approach to Japanese Mimetics*

Kimi Akita Osaka University

1. Introduction

This paper presents some initial findings about our frame-semantic, ‘encyclopedic’ knowledge as an essential factor in the functional and formal peculiarities of sound-symbolic words with special reference to Japanese mimetics (or ideophones). Japanese is an agglutinative SOV language with a rich sound-symbolic, ‘mimetic’ sub-lexicon. Japanese mimetics can depict both auditory (e.g., (1a, b)) and non-auditory eventualities and entities (e.g., (1c-f)).1

(1) a. Neko-ga nyaa-to nai-ta. (voice) cat-NOM MIM-QUOT cry-PST

‘A cat cried meow.’

b. Kaminari-ga gorogoro nat-te i-ta. (noise) thunder-NOM MIM sound-CONJ be-PST

‘A thunder was sounding rumble-rumble.’

c. Hosi-ga kirari-to kagayai-ta. (visual experience) star-NOM MIM-QUOT shine-PST

‘A star shone glitteringly.’

d. Hada-ga betobeto su-ru. (texture) skin-NOMMIM do-NPST

‘[My] skin feels sticky.’

e. Atama-ga zukin-to itan-da. (bodily sensation)

* This study was partly supported by Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (#24720179) and a grant for Proyectos de Investigación Fundamental no Orientada (Tipo A) (#FEI2010-14903; PI: Iraide Ibarretxe-Antuñano). Email: akitambo@lang.osaka-u.ac.jp.

1 The abbreviations and symbols used in this paper are as follows: ACC = accusative; © = distinctly childish and/or colloquial; CL = classifier; CONJ = conjunctive; COP = copula; DAT = dative; GEN = genitive; MIM = mimetic; N = moraic nasal (only for mimetics); NML = nominalizer; NOM = nominative; NPST = nonpast; POL = polite; PST = past; Q = geminate (only for mimetics); QUOT = quotative; TOP = topic.

To appear in Proceedings of the Czuczor-Fogarasi Conference, Budaörs, Hungary.

head-NOM MIM-QUOT hurt-PST

‘[My] head hurt throbblingly.’ f. Moo unzari-da. (emotion) now MIM-COP

‘[I]’m fed up now.’

The study of Japanese mimetics has a long history. However, it has not been until recently that Japanese linguists have turned their attention from the descriptive to theoretical importance of this word class. Hamano (1998) is a landmark study in this move. She presents a comprehensive description of the phonosemantic system of Japanese mimetics. Kita (1997) also made a significant contribution, positing a separate semantic dimension (called ‘the affecto-imagistic dimension’) for mimetics. Nasu (2002) reveals some phonological patterns in mimetics, which are accounted for in terms of general phonological constraints. Tsujimura (2005), Kageyama (2007), and Toratani (2007) discuss grammatical issues (e.g., the syntax-semantics interface) from the viewpoints of Construction Grammar, Lexical Conceptual Semantics, and Role and Reference Grammar, respectively.

In Akita (2012a, c), which is summarized in Section 3 below, I proposed a frame-semantic interpretation of the semantic peculiarity of mimetics. Previous studies have described sound-symbolic words, such as mimetics, as ‘vivid’ (Doke 1935, 118), ‘expressive’ (Samarin 1971), ‘eloquent’ (Johnson 1976, 240), ‘dramaturgic’ (Voeltz and Kilian-Hatz 2001, 5), etc. In frame-semantic terms (Fillmore 1982; Fillmore and Baker 2010), these semantic characterizations of mimetics can be restated more objectively as ‘high frame-specificity’. The present study pursues this frame-semantic approach to mimetic semantics based on my recent investigations.

The organization of this paper is as follows. Section 2 introduces the basic notions of Frame Semantics. Section 3 briefly summarizes the results of a corpus-based study on the collocation between mimetics and verbs. Section 4 observes the semantic extension of mimetics, which often involves metonymy, a frame-internal association. Section 5 discusses the role of the rich frame semantics of mimetics in their unconventional verbalization. Section 6 demonstrates how the frame semantics of mimetics determines their formal properties, such as morphological and segmental patterns. Section 7 considers the frame-semantic basis of the special pragmatic function of mimetics, which has been noted in the literature. Section 8 concludes the paper.

2. Frame Semantics

This section outlines Frame Semantics (Fillmore 1982; Fillmore and Baker 2010; inter alia). In this framework of semantics, the meanings of linguistic signs are analyzed in light of the rich background knowledge (i.e., semantic frame), which is abstracted from our real-world experiences. Each lexical unit ‘evokes’ a frame and the frame is schematically structured with several fine-grained semantic roles called ‘frame elements’ (FEs). FrameNet is a frame-based online lexical resource that is being developed in some languages, including English, German, Spanish, Swedish, and Japanese. It provides corpus texts annotated for frames, which are related to one another in various ways (‘frame-frame relations’; e.g., Inheritance, Perspectivization, Using, Subframe, Precedence, Causativization).

Take the Self_motion frame as an example. This frame is primarily defined as follows:

‘The SELF_MOVER, a living being, moves under its own direction along a PATH’ (Berkeley FrameNet, last accessed 29 August 2012). (Frame names and FEs are given in Courier fonts and SMALL_CAPITALS, respectively.) The lexical units that evoke this frame include manner-of-motion verbs (e.g., walk, run, roam, scurry) and motion-related nouns (e.g., hike, step, walk, way). (Frame Semantics allows cross-categorial grouping like this.) The FEs of this frame are not limited to those that constitute the core of a self-motion event (‘core FEs’; e.g., AREA,SELF_MOVER,DIRECTION,SOURCE,PATH,GOAL); they also include the peripheral conceptual components of the event (‘non-core FEs’; e.g., DISTANCE, EXTERNAL_CAUSE, INTERNAL_CAUSE,MANNER,MEANS,PURPOSE,SPEED,TIME). The frame ‘inherits’ from the Intentionally_act and Motion frame, is ‘inherited’ by the Fleeing and Travel frames, and has the Quitting_a_place frame as its ‘subframe’.

Despite their rich ‘situational’ semantics, mimetics have not been discussed in the frame-semantic context, perhaps due to their general exclusion from linguistic theories. However, there are some recent approaches to the encyclopedic semantics of mimetics that appear to be reinterpretable in terms of frames. Kita (1997, 406) argues that mimetics evoke what he calls ‘proto-eventualities’, in which ‘perceptual-motor information is temporally organized with contingent affective information’. In their analysis of mimetic polysemy, Lu (2006) and Inoue (2010) posit Idealized Cognitive Models (Lakoff 1987) and

‘phenomenemes/schemata’ (Kunihiro 1994), respectively. Hasada (2001) adopts Natural Semantic Metalanguage (Wierzbicka 1972) in her detailed descriptions of the prototype scenarios for some mimetics for emotion. Hasebe (2012) and Usuki and Akita (2012) apply

‘qualia structure’ (Pustejovsky 1995) in their lexical-semantic analyses of the morphosyntactic realizations of mimetics. I expect that the present frame-semantic approach

to mimetic semantics is potentially interchangeable with and complementary to these independently applied models. In what follows, I will demonstrate how promising this approach is.

3. Collocability

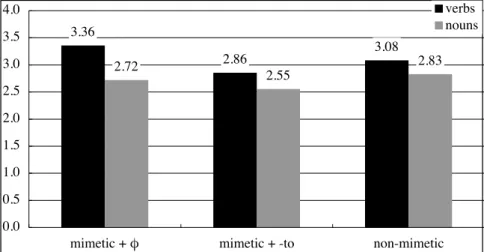

A clear index of the frame-semantic specificity of mimetics is their strong collocation with certain types of verbs. In Akita (2012a, c), I compared the collocability of reduplicative mimetic adverbs (the most common type in Japanese) and that of non-mimetic adverbials (e.g., isoi-de ‘hurriedly’, issyookenmei ‘hard’) in corpora of spoken and written Japanese. Mimetics were considered in two ways—with and without optional quotative -to-marking—which are known to affect their collocability (Toratani 2006; Akita and Usuki 2012). Figure 1 shows the mean collocational strength (t-value) between the three types of adverbials on the one hand and verbs and nouns on the other.

3.36

2.86

3.08

2.72 2.55

2.83

0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0 3.5 4.0

mimetic + φ mimetic + -to non-mimetic verbs nouns

Figure 1. The collocational strength of mimetic/non-mimetic adverbials and verbs/nouns (translated from Akita 2012a)

Unpaired t-tests revealed that the verbal collocation of bare mimetics is stronger than those of to-marked mimetics (t (117) = 2.35, p < .05) and non-mimetic adverbials (t (102) = 1.81, p

= .07). No significant difference was obtained for their nominal collocation.

Moreover, I applied the FrameNet-style coding to the significant collocates of the adverbials. The frame-semantic relations between the collocates of each adverb were classified into five categories: identical (evoking the same frame), related (evoking related frames), core FE instantiating (one collocate instantiating a core FE of the frame evoked by

another collocate), non-core FE instantiating (one collocate instantiating a non-core FE of the frame evoked by another collocate), and unrelated (no evident frame-semantic relation found). The two sentences in (2) illustrate the verbal collocation of the -to-marked mimetic sutasuta-to ‘walking briskly’. The manner-of-motion verb aruk- ‘walk’ in (2a) evokes the Self_motion frame. This frame inherits general Motion, which ik- ‘go’ in (2b) evokes.

(2) Related:

a. Kanozyo-wa… wazukani ik-ken-hodo-no kyori-o oi-te, she-TOP only 1-CL-about-GEN distance-ACC place-CONJ

otoko-no-yoo-ni sutasuta-to arui-te ku-ru. man-GEN-like-COP MIM-QUOT walk-CONJ come-NPST

‘She comes walking briskly like a man, keeping a distance of only one ken (about 1.82 m) or so [from me].’

(K. Okamoto, Hansiti torimono-tyoo [Detective Hanshichi’s diary]) b. … sutasuta-to rooka-o ik-u-no-o, mamakko-no-yoo-na metuki-de MIM-QUOT hallway-ACC go-NPST-NML-ACC stepchild-GEN-like-COP look-with mi-nagara…

look-while

‘… seeing [her] go briskly in the hallway with a stepchild-like look…’

(K. Izumi, Mayu-kakusi-no rei [How beautiful without eyebrows])

The following sentences contain the typical collocates of the mimetic kotukotu ‘tap-tap’: the verb tatak- ‘hit’ in (3a) and the noun tobira ‘door’ in (3b). The latter instantiates a core FE (i.e., IMPACTEE) of the frame evoked by the former (i.e., Impact).

(3) Core FE instantiating:

a. Moo hitugi-no huta-o, kotukotu-to tatak-u mono-ga at-te-mo already coffin-GEN lid-ACC MIM-QUOT hit-NPST person-NOM be-CONJ-even i-i-hazu-da

good-NPST-must-COP

‘It’s about time someone knocked tap-tap at the lid of the coffin [in which I am]’ (J. Unno, Sennengo-no sekai [The world in a thousand years]) b. Zimusyo-no tobira-o kotukotu tatak-u mono-ga ari-mas-u.

office-GEN door-ACCMIM hit-NPST person-NOM be-POL-NPST

‘Someone is knocking tap-tap at the door of the office.’

(K. Miyazawa, Neko-no zimusyo [The cat’s office])

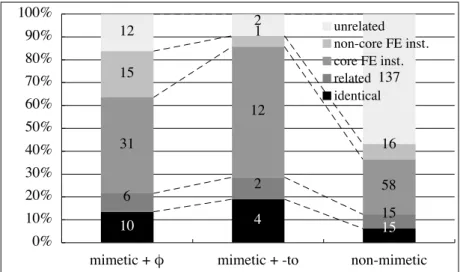

Figure 2 summarizes the results.

10 4 15

6

15 31

12

58 15

1

16

12 2

137

2

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

mimetic + φ mimetic + -to non-mimetic unrelated non-core FE inst. core FE inst. related identical

Figure 2. The frame-semantic relationships between the collocates of mimetic and non-mimetic adverbials (translated from Akita 2012a)

It was found that non-mimetic adverbials are much less likely to collocate with frame-semantically related verbs and nouns (i.e., those classified as ‘identical’, ‘related’, and

‘core/non-core FE instantiating’) (43.15%) than mimetics, whether followed by the quotative particle (90.48%) or not (83.78%) (χ2 (2) = 49.13, p < .001; adjusted residual = −6.99, p

< .001). -To-marked and bare mimetics exhibited no significant difference (χ2 (1) = .58, p

= .45).

The two sets of results here show that Japanese mimetics, particularly bare ones, have a strong semantic association with verbs. This appears to be ascribed to the nature of the frames mimetics evoke. Actual instances, such as (2) and (3), suggest that mimetic frames are elaborations of verb frames. In other words, mimetic frames ‘inherit’ verb frames (cf. Toratani 2007). For example, sutasuta ‘walking briskly’ in (2) specifies the manner component of the meaning of the verb aruk- ‘walk’, which is a typical predicate for the mimetic. Likewise, kotukotu ‘hitting with a tapping noise’ in (3) represents a specific type of hitting, enriching the event information provided by the verb tatak- ‘hit’. Based on Akita and Usuki’s (2012) observation that bare mimetics form a complex predicate with their host verbs, the distinguished collocability of bare mimetics shown in Figure 1 can be understood as a result of the complete frame integration between mimetics and verbs. Put differently, the formal integration (i.e., compounding) is motivated by the compatibility (or inheritance)

between mimetic frames and verb frames.

4. Semantic extension

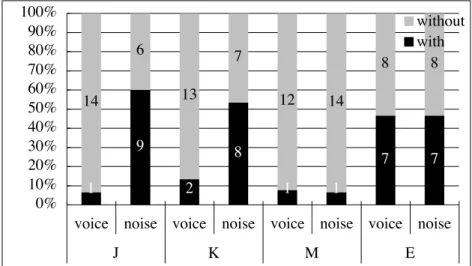

This section presents a further investigation into the richness and specificity of the frames evoked by mimetics, focusing on their semantic extension (Akita, in preparation). A comparative examination of thirty sound mimetics (15 for voice, 15 for noise) from Japanese, Korean, Mandarin Chinese, and English revealed two interesting facts: the low extensibility of voice mimetics and the prevalence of metonymical extension in Japanese mimetics.

The investigation was conducted by using dictionaries of mimetics in the four languages and consulting one or two native speakers. The dictionaries used are Kakehi et al. (1996) (Japanese), Aoyama (1991) (Korean), Noguchi (1995) (Mandarin), and Kloe (1977) (English). Only thirteen voice mimetics were obtained in Mandarin, which appears to have no mimetic form for humming of a crowd and grumbling.

First, polysemy was found to be rare in voice mimetics across languages, except for English. For example, the mimetics for mice’s sound in the three languages (tyuutyuu in Japanese, ccikccik in Korean, jiji in Mandarin) do not have a non-sound meaning, whereas English squeak can mean ‘be in time’ and ‘tip off’. Figure 3 shows how many sound mimetics in the four languages have a non-auditory meaning as well.

1 9

2 8

1 1

7 7

14 6

13 7

12 14

8 8

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

voice noise voice noise voice noise voice noise

J K M E

without with

Figure 3. The number of sound mimetics with non-auditory meanings

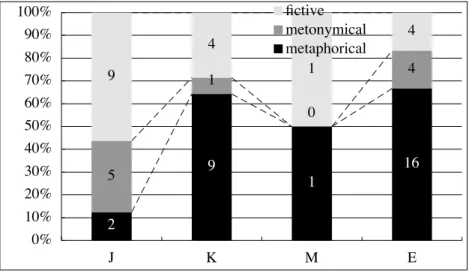

Second, a closer look at the polysemous mimetics found out that metonymical extension is particularly common in Japanese mimetics. As Mikami (2006) and Toratani (2012) discuss,

Japanese mimetics exhibit many instances of ‘fictivity’ in the sense of Talmy (1996). Fictive expressions in the current context can be considered a kind of metonymical expressions. They represent particular states by referring to hypothetical events preceding or following them. For example, gorogoro, which typically represents the rolling motion of a large globular object (e.g., rock), can depict the state of large objects lying about everywhere. This is an example of Kunihiro’s (1985) ‘vestigial cognition’. In the present case, large objects’ state of lying about everywhere is represented by referring to the hypothetical rolling motion they would have undergone to reach their current positions. Meanwhile, karikari can represent the crispiness of bacon by imitating the hypothetical sound that the bacon would make if we bite or cut it. This is an example of ‘prospective cognition’ (Nakamoto 2008). The present results with many such cases, diagrammed in Figure 4, serve as partial quantitative support for these previous findings.

2

9

1 5 16

1

0 9 4

4

1

4

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

J K M E

fictive metonymical metaphorical

Figure 4. Types of semantic extension in mimetics

Note: ‘Metonymical’ and ‘metaphorical’ cases are those of non-fictive metonymy and non-metonymical metaphor, respectively.

These two results are compatible with our frame-semantic view of mimetics (see Yu 2012 for image-schematic visualization of a similar analysis). On the one hand, polysemy of voice mimetics is rare because their frames are likely to only consist of two core FEs: namely, the voice and an animate entity that made it spontaneously. On the other hand, many noise mimetics in Japanese undergo metonymical extension, which takes place within a frame (Croft 1993). Unlike voice mimetics, noise mimetics typically evoke a frame in which someone/something acts on someone/something else in a particular manner and the contact between the two participants (or core FEs) causes a change of state (another core FE) in the

second participant that is accompanied by the emission of a particular sound (still another core FE) (see Levin et al. 1997 for the distinction between internally and externally caused sound emission). This frame-semantic complexity offers itself as a basis for frame-internal extension. To conclude, Japanese mimetics evoke such specific frames that they have better access to this route of semantic extension than mimetics in other languages.

5. Colloquial verbalization

The idea of frame-semantic specificity also accounts for unconventional verbal uses of mimetics (Akita 2012b). As Tsujimura (2009) and Toratani (forthc) discuss, Japanese has a highly productive verbalizing strategy for mimetics: [MIM + su- ‘do’] (see also Hamano and Sugahara, this volume). In the conventional use of Japanese, this strategy is only available to mimetics with relatively low iconicity, such as mimetics for certain types of motion (e.g., burari-to su- ‘ramble’, urouro su- ‘loiter’) and emotion (e.g., bikkuri su- ‘be astounded’, wakuwaku su- ‘be excited’) (Akita 2009, Ch. 6). However, colloquial discourse permits the verbalization of highly iconic mimetics, such as mimetics for noise (e.g., (4)) and step (e.g., (5)). Nevertheless, as illustrated in (6), voice mimetics are unlikely to form a verb.

(4) Mimetics for noise:

a. ©Ni-kai-no zyuunin-ga tenzyoo-o dondon si-ta. 2-floor-GEN resident-NOM ceiling-ACC MIM do-PST

‘The resident on the second floor stomped on the ceiling.’ b. ©Gisi-ga kikai-o gatyagatya si-ta.

engineer-NOM machine-ACC MIM do-PST

‘The engineer clanked the machine.’

(5) Mimetics for step:

a. ©??Gakusei-ga rozi-de tobotobo si-te i-ta. student-NOM alley-in MIM do-CONJ be-PST

‘A student was plodding on the alley.’

b. ©?Kodomo-ga rooka-o tokotoko si-te i-ta. child-NOM hallway-ACC MIM do-CONJ be-PST

‘A child was toddling in the hallway.’

(6) Mimetics for voice:

a. *Otoko-wa geragera si-te i-ta. man-TOP MIM do-CONJ be-PST

‘The man was guffawing.’

b. *?Neko-ga soto-de nyaanyaa si-te i-ta. cat-NOM outside-in MIM do-CONJ be-PST

‘A cat was meowing outside.’

Verbs predicate eventualities. The following tests, in which mimetics with low iconicity successfully modify a noun that denotes an eventuality itself, show that they represent the entire motion/emotion event (see Akita 2010). In this sense, these mimetics have particularly verb-like frames (see Section 3), which appear to enable them to form verbs.

(7) a. {burari/urouro} -to iw-u kooi (motion) MIM -QUOT say-NPST action

‘the action of {rambling/loitering}’

b. {bikkuri/wakuwaku} -to iw-u keiken (emotion) MIM -QUOT say-NPST experience ‘the experience of being {astounded/excited}’

In contrast, mimetics with high iconicity, as tested in (8), tend to focus on a particular subpart (or FE) of their referent event frames, such as noise, step, and voice. This appears to be why these mimetics cannot freely be verbalized to describe the entire eventualities.

(8) a. {dondon/gatyagatya} -to iw-u {oto/ ??kooi} (noise) MIM -QUOT say-NPST sound action ‘the {sound/??action} of {stomping/clanking}’

b. {tobotobo/tokotoko} -to iw-u {asidori/ ?*kooi} (step) MIM -QUOT say-NPST step action ‘the {step/*action} of {plodding/toddling}’

c. {geragera/nyaanyaa} -to iw-u {koe/ *kooi} (voice) MIM -QUOT say-NPST voice action ‘the {voice/*action} of {guffaw(ing)/meow(ing)}’

The frame-semantic account is further applicable to the acceptability difference in

colloquial verbalization between the noise/step mimetics in (4) and (5) and the voice mimetics in (6). As discussed in Section 4, noise mimetics typically evoke a complex frame of impact, in which one FE acts on another in a particular manner that may be accompanied by a particular sound, whereas voice mimetics evoke a simple frame of spontaneous vocalization. The former frame allows noise mimetics to metonymically access the impact information, which is absent in the latter purely auditory frame. Mimetics for step are similar to mimetics for noise. They refer to the self-mover’s step that tells us metonymically what the motion event is like. Thus, like their semantic extension discussed in Section 4, the morphosyntactic extension of mimetics is motivated and constrained by the internal structure of their frames.

6. Template and root selection

Our frame-semantic account of the peculiarities of mimetics can be further extended to their morphological, prosodic, and segmental components. An iconic relation between a signifier and a signified, such as the form and meaning of a mimetic, by definition does not entail causality from one to the other. However, some formal features of mimetics are clearly motivated by their lexical meanings.

First, the morphological shapes of most mimetics in Japanese depend on the aspectual contour of their referent eventualities (Akita 2009, Ch. 5). For example, it is true in many languages that most mimetics for manner of motion take a reduplicative form (Hinton et al. 1994; Ibarretxe-Antuñano 2006), as illustrated by tobotobo ‘plodding’, tokotoko ‘toddling’, and urouro ‘loitering’ in Section 6. This is because self-motion is a durative event that typically consists of a series of footsteps. Similarly, suffixal mimetic templates, such as CVCVQ and CVCVN, are employed for mimetics for punctual events, such as pataQ ‘flop’ and koron ‘rolling over’. These aspectual features constitute the core of the frames evoked by the mimetics. Therefore, it seems safe to conclude that these templates are iconically motivated by the temporal structure of those mimetic frames.

Second, even sound symbolism has a frame-semantic basis. The idea is the same as the one behind template selection. Oseki (2013) discusses a clear example. She observes voicing contrasts of mimetics like (9), which are associated with their contrasts in affectedness. The noisy bang imitated by dondon, but not the light tap imitated by tonton, is compatible with the situation in which a man is striking his head on the floor in anger. In other words, this particular event (or context) motivates the initial voiced obstruent of the mimetic.

(9) Taroo-ga ikari-kurut-te atama-o yuka-ni {dondon/*tonton} -to T-NOM get.angry-go.mad-CONJ head-ACC floor-DATMIM -QUOT

tataki-tuke-ta. hit-attach-PST

‘Taro went mad and struck [his] head {bang-bang/*tap-tap} on the floor.’ (Oseki 2013)

Similar observations would be possible for many other sound-symbolic formal features of mimetics, including consonants and vowels in each root-internal position (cf. Hamano and Sugahara, this volume). Importantly, the frame-semantic motivations discussed here are largely unique to mimetics, iconic lexical items. The present discussion points to the need for lexical-semantic considerations in phonosemantics, whose investigations, notably those in experimental psychology, have mostly focused on sound before meaning.

7. Pragmatic functions

Finally, I briefly discuss the frame-semantic basis of the pragmatic functions of mimetics. Based on her field study in Pastaza Quechua, Nuckolls (1996, Ch. 5) develops the concept of

‘sound-symbolic involvement’ as an essential function of mimetics in conversation (see also Baba 2003). More recently, Dingemanse (2011, Ch. 11) notes the performative function of mimetics in his conversation analysis in Siwu (a Niger-Congo language). He attributes this pragmatic function to mimetics’ representational status as ‘depiction’, rather than

‘description’. The depictive semantics of mimetics appears to more or less correspond to or cover what we call (lexical) iconicity and frame-specificity. Mimetics depict actual eventualities in a highly specific, imitative, and holistic fashion. The speaker uses this elaborate replication of an eventuality as an ‘interactive frame’ (i.e., the background context of a linguistic interaction; Tannen and Wallat 1987), which facilitates the hearer’s understanding of the replicated situation in which s/he is expected to be involved (see also Kita 1997, 406).

Obviously, these (semiotic-semantic-)pragmatic models need further refinement and verification from both qualitative and quantitative angles. In such inquiries, the Japanese language will carry particular significance, as it provides various large-scale mimetic-rich databases annotated for various purposes (for a quantitative approach to mimetic pragmatics, see Akita et al. 2012). Note that the previous studies on the use of mimetics have been mostly

based on experimental or field-recorded data of relatively limited size.2

8. Conclusion

This paper has illustrated the effectiveness of a frame-semantic account of the marked properties of Japanese mimetics. We observed that mimetics generally evoke a specific eventive frame. This idea captures the collocability, semantic extensibility, verbalizability, template/root selection, and pragmatic functions of mimetics. From an educational point of view, the present findings suggest the usefulness of different media in teaching/learning different types of mimetics (e.g., videos/animations of impact events for noise mimetics; collocational information for mimetics for motion, pain, emotion, etc.). I hope that the current study has successfully provided a theoretical basis for future research and application along these lines.

References

Akita, Kimi. 2009. A Grammar of Sound-Symbolic Words in Japanese: Theoretical Approaches to Iconic and Lexical Properties of Mimetics. Ph.D. dissertation, Kobe University.

Akita, Kimi. 2010. An Embodied Semantic Analysis of Psychological Mimetics in Japanese. Linguistics 48, 6: 1195-220.

Akita, Kimi. 2012a. Kyooki-tokusei-kara miru onomatope-no hureemu-imiron [The frame semantics of mimetics in terms of their collocational characteristics]. In Shinohara and Uno (2012), Chapter 6.

Akita, Kimi. 2012b. A Frame-Semantic Analysis of the (Limited) Flexibility of Mimetic Verbs. Proceedings of the 30th Annual Meeting of the English Linguistic Society of Japan.

Akita, Kimi. 2012c. Toward a Frame-Semantic Definition of Sound-Symbolic Words: A Collocational Analysis of Japanese Mimetics. Cognitive Linguistics 23, 1: 67-90.

Akita, Kimi. In preparation. Iconicity and Mimetic Polysemy.

Akita, K., S. Nakamura, T. Komatsu, and S. Hirata. 2012. A Quantitative Approach to Sound-Symbolic Involvement. Paper presented at Sound Symbolism Workshop 2012, Keio University, Mita Campus, Tokyo, 7 August 2012.

Akita, Kimi, and Takeshi Usuki. 2012. A Constructional Account of the Morphological Optionality of Japanese Mimetics. Ms., Osaka University and Fukuoka University.

Aoyama, Hideo. 1991. Tyoosengo syootyoogo-ziten [A dictionary of Korean sound-symbolic words]. Tokyo: Daigaku Shorin.

Baba, Junko. 2003. Pragmatic Function of Japanese Mimetics in the Spoken Discourse of Varying Emotive Intensity Levels. Journal of Pragmatics 35, 12: 1861-89.

2 Other presumable pragmatic features of mimetics, such as precision and comicalness, will also be worth considering in terms of frames.

Croft, William. 1993. The Role of Domains in the Interpretation of Metaphors and Metonymies. Cognitive Linguistics 4, 4: 335-70.

Dingemanse, Mark. 2011. The Meaning and Use of Ideophones in Siwu. Ph.D. dissertation, Radboud University/Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, Nijmegen.

Doke, Clement Martyn. 1935. Bantu Linguistic Terminology. London: Longmans, Green.

Fillmore, Charles J. 1982. Frame Semantics. In Linguistics in the Morning Calm, ed. The Linguistic Society of Korea, 111-37. Seoul: Hanshin.

Fillmore, Charles J., and Collin Baker. 2010. A Frames Approach to Semantic Analysis. In The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Analysis, eds. Bernd Heine and Heiko Narrog, 313-40. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hamano, Shoko. 1998. The Sound-Symbolic System of Japanese. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications. Hasada, Rie. 2001. Meanings of Japanese Sound-Symbolic Emotion Words. In Emotions in

Crosslinguistic Perspective, eds. Jean Harkins and Anna Wierzbicka, 217-53. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Hasebe, Ikuko. 2012. Nitieigo-no gitaigo/giongo-ni tuite [On mimetic words and onomatopoeia in Japanese and English]. JELS 29: 31-37.

Hinton, Leanne, Johanna Nichols, and John J. Ohala, eds. 1994. Sound Symbolism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Iraide. 2006. Sound Symbolism and Motion in Basque. Munich: LINCOM Europa.

Inoue, Kazuko. 2010. Onomatope-no retorikku: Giongo/gitaigo-hyoogen-no soohatu-ni kansuru ninti-gengogakuteki-kenkyuu [Rhetoric of onomatopoeia: Cognitive linguistic study on neologism of onomatopoeia and mimetics]. Ph.D. dissertation, Osaka University.

Johnson, Marion R. 1976. Toward a Definition of the Ideophone in Bantu. Ohio State University Working Papers in Linguistics 21: 240-53.

Kageyama, Taro. 2007. Explorations in the conceptual semantics of mimetic verbs. In Current Issues in the History and Structure of Japanese, eds. Bjarke Frellesvig, Masayoshi Shibatani, and John Smith, 27-82. Tokyo: Kurosio Publishers.

Kakehi, Hisao, Ikuhiro Tamori, and Lawrence C. Schourup. 1996. Dictionary of Iconic Expressions in Japanese. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Kita, Sotaro. 1997. Two-Dimensional Semantic Analysis of Japanese Mimetics. Linguistics 35, 2: 379-415.

Kloe, Donald R. 1977. A Dictionary of Onomatopoeic Sounds, Tones and Noises in English and Spanish Including Those of Animals, Man, Nature, Machinery and Musical Instruments, Together with Some that Are Not Imitative or Echoic. Detroit, MI: Blaine Ethridge.

Kunihiro, Tetsuya. 1985. Ninti-to gengo-hyoogen [Cognition and linguistic expressions]. Journal of the Linguistic Society of Japan 88: 1-19.

Kunihiro, Tetsuya. 1994. Nintiteki-tagiron: Gensyooso-no teisyoo [Cognitive polysemy: Proposing the concept of ‘phenomeneme’]. Journal of the Linguistic Society of Japan 106: 22-45.

Lakoff, George. 1987. Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal about the Mind. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Levin, Beth, Grace Song, and B.T.S. Atkins. 1997. Making Sense of Corpus Data: A Case Study of Verbs of Sound. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 2, 1: 23-64.

Lu, Chiarung. 2006. Giongo/gitaigo-no hiyuteki-kakutyoo-no syosoo: Ninti-gengogaku-to ruikeiron-no kanten-kara [Aspects of figurative extension of mimetics: From the cognitive linguistic and typological perspectives]. Ph.D. dissertation, Kyoto University.

Mikami, Kyoko. 2006. Nihongo-no giongo/gitaigo-ni okeru imi-no kakutyoo: Konsekiteki-ninti/yokiteki-ninti-no kanten-kara [Semantic extension in Japanese mimetics: From the perspective of vestigial/prospective cognition]. Nitigo/nitibungaku kenkyuu [Studies on Japanese language and literature] 57, 1: 199-217.

Nakamoto, Koichiro. 2008. Yoki-no koozoo-to gengo-rikai [Prospective cognition and its linguistic

realization]. Studies in Cognitive Linguistics 8: 81-124. Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo.

Nasu, Akio. 2002. Nihongo-onomatope-no gokeisei-to inritu-koozoo [Word formation and prosodic structure of Japanese mimetics]. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Tsukuba.

Noguchi, Munechika. 1995. Tyuugokugo giongo-ziten [A dictionary of Chinese sound mimetics]. Tokyo: Toho Shoten.

Nuckolls, Janis B. 1996. Sounds like Life: Sound-Symbolic Grammar, Performance, and Cognition in Pastaza Quechua. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Oseki, Mai. 2013. Nihongo-onomatope-no yuusei/musei-no tairitu-ni okeru onsyootyoo-to tadoosei [Sound symbolism and transitivity in the voicing contrasts of Japanese mimetics]. M.A. thesis, Hokkaido University.

Pustejovsky, James. 1995. The Generative Lexicon. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Samarin, William J. 1971. Survey of Bantu Ideophones. African Language Studies 12: 130-68. Shinohara, Kazuko, and Ryoko Uno, eds. 2012. Tikazuku oto-to imi: Onomatope-kenkyuu-no syatei

[Approaching sound and meaning: The range of studies in sound symbolism]. Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo.

Talmy, Leonard. 1996. Fictive Motion in Language and ‘Ception’. In Language and Space, eds. Paul Bloom, Mary A. Peterson, Lynn Nadel, and Merrill F. Garrett, 211-76. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Tannen, Deborah, and Cynthia Wallat. 1987. Interactive Frames and Knowledge Schemas in Interaction: Examples from a Medical Examination/Interview. Social Psychology Quarterly 50, 2: 205-16.

Toratani, Kiyoko. 2006. On the Optionality of To-Marking on Reduplicated Mimetics in Japanese. In Japanese/Korean Linguistics, Vol. 14, eds. Timothy J. Vance and Kimberly Jones, 415-22. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.

Toratani, Kiyoko. 2007. An RRG Analysis of Manner Adverbial Mimetics. Language and Literature 8, 1: 311-42.

Toratani, Kiyoko. 2012. Hukusi-onomatope-no tokusyusei: Tagisei/zisyoosei-kara-no koosatu [Peculiarities of adverbial mimetics: From the perspectives of polysemy and eventivity]. In Shinohara and Uno (2012), Chapter 5.

Toratani, Kiyoko. Forthcoming. Constructions in RRG: A Case Study of Mimetic Verbs in Japanese. Tsujimura, Natsuko. 2005. A Constructional Approach to Mimetic Verbs. In Grammatical

Constructions: Back to the Roots, eds. Mirjam Fried and Hans C. Boas, 137-54. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Tsujimura, Natsuko. 2009. Onomatope-doosi-no imi/koo-koozoo-no iti-koosatu [Reexamination of the meaning and argument structure of mimetic verbs]. KLS 29: Proceedings of the Thirty-Third Annual Meeting of the Kansai Linguistic Society, 334-43.

Usuki, Takeshi, and Kimi Akita. 2012. A Qualia Account of Mimetic Resultatives in Japanese. Poster presented at the 22nd Japanese/Korean Linguistics Conference, National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics, Tokyo, 12 October 2012.

Voeltz, Friedrich K. Erhard, and Christa Kilian-Hatz, eds. 2001. Ideophones, 193-204. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Wierzbicka, Anna. 1972. Semantic Primitives. Frankfurt: Athenäum.

Yu, Wei-Lun. 2012. Hureemu-no kanten-kara miru nihongo-no giongo: Imi-to imi-kakutyoo-o tyuusin-ni [Japanese sound mimetics in terms of frames: Focusing on meaning and its extension]. Ms., Kobe University.