Fiction in an Encyclopedia:

A Generative Lexicon Approach to Fictive Mimetic Resultatives in Japanese* Takeshi Usuki and Kimi Akita

1. Introduction

This paper proposes a Generative Lexicon account for the non-uniform behavior of resultative expressions with sound-symbolic, mimetic words—or mimetic resultatives—in Japanese. We pay special attention to the two types of “fictivity” exhibited by mimetic resultatives that determine their morphological possibilities. By extending the qualia-structural description of lexical semantics, which has mainly been adopted for nouns (and, occasionally, for verbs), to mimetics, we elucidate their rich encyclopedic meaning and its correlation with morphosyntactic realization.

Mimetic resultatives are instantiated by two major morphosyntactic types of mimetics, which are quotative/bare ([MIM(-to)]) and copulative ([MIM-ni]), as in (1).1, 2

(1) Mary-ga eda-o {boQkiri(-to)/ bokiboki-ni} ot-ta. Mary-NOM branch-ACC MIM-QUOT MIM-COP break-PST

‘Mary completely broke the branch.’

This formal diversity of mimetic resultatives has been largely ignored in previous research, given that quotative/bare mimetics typically represent manner, as illustrated in (2a), whereas copulative mimetics consistently represent some type of (result) state, as illustrated in (2b) (Tamori (1984); cf. Toratani (2013)).

(2) a. Quotative/bare:

Mary-ga eda-o bokiboki(-to) ot-ta. (manner) Mary-NOM branch-ACC MIM-QUOT break-PST

‘Mary forcefully broke the branches.’ b. Copulative:

Sono eda-wa bokiboki-dat-ta. (state) that branch-TOP MIM-COP-PST

‘The branch was completely broken.’

Thus, the aim of the present paper is to classify and describe the formal and functional

[SEMI-FINAL VERSION] Usuki, Takeshi, and Kimi Akita. 2013. Fiction in an encyclopedia: A Generative Lexicon approach to fictive mimetic resultatives in Japanese. In Fukuoka Linguistic Circle, ed., Gengogaku-kara-no tyooboo 2013: Hukuoka-gengo-gakkai 40-syuunen-kinen-ronbunsyuu [A view from linguistics 2013: Papers on the 40th anniversary of Fukuoka Linguistic Circle], 308-321. Kyushu: Kyushu University Press.

properties of mimetic resultatives and to discuss them from the viewpoint of Generative Lexicon. The specific organization of the paper is as follows. Section 2 outlines the morphological and functional features of mimetics, which set the basis for the subsequent discussion. This section also introduces the two types of fictivity that are relevant to mimetics. This notion critically differentiates between two major types of mimetic resultatives, which are described in Section 3. Section 4 provides a qualia-structural account of the distinct characteristics of the two types of mimetic resultatives, which demonstrates the grammatical relevance of the holistic semantics of sound-symbolic words. Section 5 concludes the paper by discussing the theoretical implications of the current study.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Morphology and Function of Mimetics

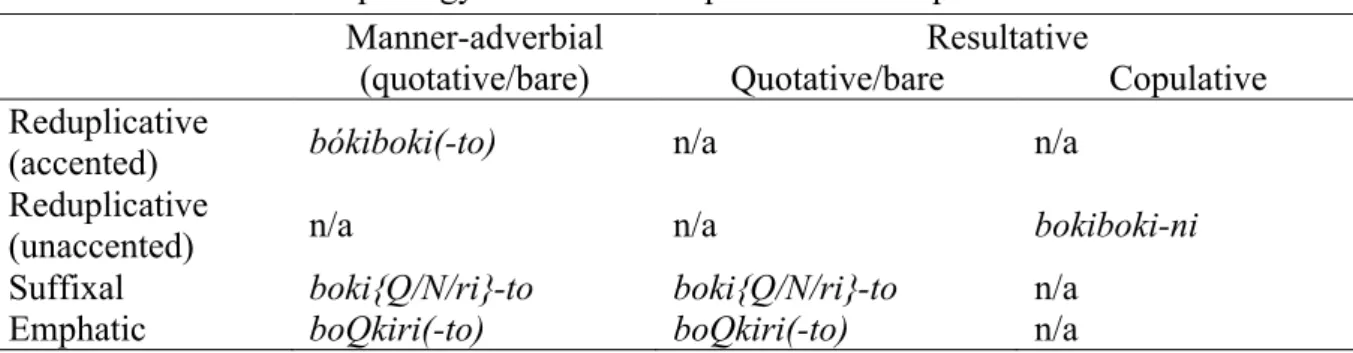

In this section, we summarize the functional possibilities of the typical morphological types of mimetics. Quotative/bare and copulative mimetics are instantiated by different sets of mimetic forms, as shown in Table 1 (see Toratani (2013) for some apparent exceptions).

Table 1 Morphology-function correspondences in Japanese mimetics Manner-adverbial

(quotative/bare)

Resultative

Quotative/bare Copulative Reduplicative

(accented) bókiboki(-to) n/a n/a

Reduplicative

(unaccented) n/a n/a bokiboki-ni

Suffixal boki{Q/N/ri}-to boki{Q/N/ri}-to n/a

Emphatic boQkiri(-to) boQkiri(-to) n/a

As shown in the two columns on the right side of the table, quotative/bare resultatives are instantiated by suffixal mimetics and so-called “emphatic” mimetics, which take the C1V1CC2V2ri shape (Akita (2011)), whereas copulative resultatives are only instantiated by unaccented reduplicatives. The former types of mimetics are “multifunctional” in the sense that they appear as both manner adverbs and resultatives. The quotative marking (-to) is optional in the reduplicative and emphatic types, as indicated by parentheses (see Nasu (2002) for the phonological details of this optionality).

2.2. Fictivity in Mimetics

Mikami (2006) observed the prevalence of two types of metonymical expressions in Japanese mimetics, which were what Talmy (1996) called “fictive” expressions (see also

Toratani (2013)). The first type, called “vestigial cognition” (henceforth VC) expressions, is illustrated in (3b). As is the case for the English verb scatter, the mimetic barabara can refer both to a dynamic motion event, as in (3a), and to a spatial distribution of relatively small objects, as in (3b). The scattered movement is “vestigial” in the latter case, as the houses’ current state is metonymically represented as a result of their fictive motion.

(3) a. Gake-no ue-kara koisi-ga barabara oti-te ki-ta. cliff-GEN top-from pebble-NOM MIM fall-CONJ come-PST

‘Pebbles came scattered down from the top of the cliff.’ (lit.) b. Hatake-no naka-ni tate-uri-no purehabu-zyuutaku-ga field-GEN inside-DAT build-sell-GEN prefab-residence-NOM

barabara-to tat-te i-ru. MIM-QUOT build-CONJ be-NPST

‘Some ready-made prefabricated houses are scattered in the field.’

(Mikami (2006: 206)) The other type, termed “prospective cognition” (henceforth PC) expressions, is illustrated in (4). The mimetic katikati imitates the actual clinking sound of ice cubes in (4a). In (4b), however, the same mimetic mimics an imaginative sound that would be made if one hits on the frozen laundry. This prospective sound imitation informs us of the solidness of the laundry’s surface.

(4) a. … koori-ga katikati-to nar-u oto-ga suzusi-i. ice-NOM MIM-QUOT sound-NPST sound-NOM cool-NPST

‘… [I] find the clinking sound of ice cubes cool.’

b. … sentakumono-ga katikati-ni koot-te-simat-ta. laundry-NOM MIM-COP freeze-CONJ-end.up-PST

‘… the laundry has frozen solid.’

(Mikami (2006: 211-212)) Thus, both VC and PC expressions refer to fictive sounds or manners that are associated with their actual referent states in idealized situational schemas. VC makes use of the cause of the state, which may be readily accommodated by the agentive role of the qualia structure in the Generative Lexicon theory. PC can also be described in the agentive role, but differs from VC in that it depends on a hypothetical auditory effect that is typically caused by a hypothetical contact action, such as hitting and scrubbing, which is not central to the referent state itself (e.g., the solidness of the frozen laundry in (4b)). In Section 4, we will argue that this latter type of fictivity is unique to mimetics, which are characterized by their rich

situational meanings. Moreover, the VC/PC distinction will play a crucial role in the emergence of distinct types of mimetic resultatives.

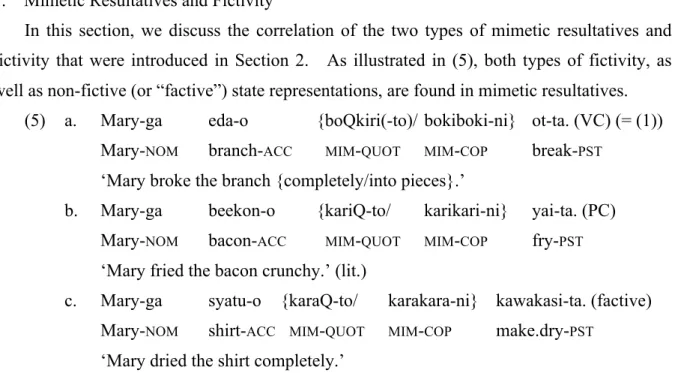

3. Mimetic Resultatives and Fictivity

In this section, we discuss the correlation of the two types of mimetic resultatives and fictivity that were introduced in Section 2. As illustrated in (5), both types of fictivity, as well as non-fictive (or “factive”) state representations, are found in mimetic resultatives.

(5) a. Mary-ga eda-o {boQkiri(-to)/ bokiboki-ni} ot-ta. (VC) (= (1)) Mary-NOM branch-ACC MIM-QUOT MIM-COP break-PST

‘Mary broke the branch {completely/into pieces}.’

b. Mary-ga beekon-o {kariQ-to/ karikari-ni} yai-ta. (PC) Mary-NOM bacon-ACC MIM-QUOT MIM-COP fry-PST

‘Mary fried the bacon crunchy.’ (lit.)

c. Mary-ga syatu-o {karaQ-to/ karakara-ni} kawakasi-ta. (factive) Mary-NOM shirt-ACC MIM-QUOT MIM-COP make.dry-PST

‘Mary dried the shirt completely.’

The broken state of the branch in (5a) is vestigially expressed in that the two relevant mimetics evoke the dynamic image of the branch-breaking event. The mimetics in (5b) prospectively represents the crunchiness of the bacon based on the sound-mimicking function. The two related mimetics in (5c) should be inherently stative, as they do not have non-stative counterparts (i.e., sound/manner meanings) (e.g., *karaQ-to {nar-/zyoohatu-su-} ‘{sound like karaQ/vapor in the karaQ manner}’). Throughout the remainder of this paper, we will focus on the first two types of mimetic resultatives (i.e., the fictive types).

First, Table 2 provides examples of some of the mimetic families that are found in the VC-type resultatives (their typical host verbs are shown in the rightmost column).

Table 2 VC-type mimetic resultatives3

Suffixal (-QUOT) Emphatic ((-QUOT))

Reduplicative

(unaccented) (-COP) Meaning V bariQ (MA/*VC) n/a baribari ‘cracked’ war- ‘break’ biriQ (MA/*VC) n/a biribiri ‘ripped’ yabur- ‘tear’ bisyoQ (MA/*VC) biQsyori bisyobisyo ‘soaked’ nure- ‘get wet’ bokiQ (MA/*VC) boQkiri bokiboki ‘broken’ or- ‘break’ bokoQ (MA/*VC) #boQkori bokoboko ‘beaten’ nagur- ‘beat’ gusaQ (MA/*VC) guQsari n/a ‘stabbed’ sas- ‘stick’ gusyoQ (MA/*VC) guQsyori gusyogusyo ‘soaked’ nure- ‘get wet’ gutyaQ (MA/?VC) guQtyari gutyagutya ‘crushed’ tubus- ‘crush’ huwaQ (MA/?VC) huNwari huwahuwa ‘fluffy’ yak- ‘bake’

n/a n/a zutazuta ‘in shreds’ sak- ‘cut up’

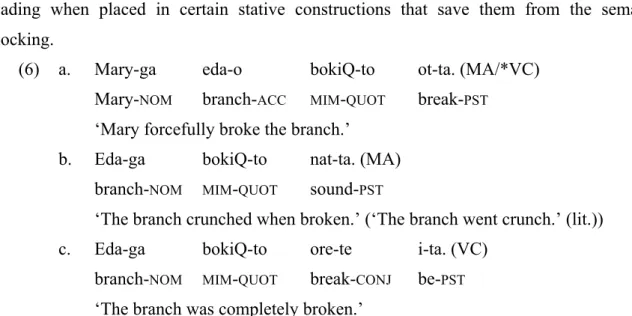

Significantly, this type of mimetic resultative is not available in suffixal forms (i.e., CVCV{Q/N/ri}), as illustrated in (6a). It appears that the resultative reading is blocked by the dominant function of suffixal mimetics as manner adverbs (abbreviated “MA”), as illustrated in (6b).4 In fact, as exemplified in (6c), some suffixal mimetics do allow a state reading when placed in certain stative constructions that save them from the semantic blocking.

(6) a. Mary-ga eda-o bokiQ-to ot-ta. (MA/*VC) Mary-NOM branch-ACC MIM-QUOT break-PST

‘Mary forcefully broke the branch.’ b. Eda-ga bokiQ-to nat-ta. (MA)

branch-NOM MIM-QUOT sound-PST

‘The branch crunched when broken.’ (‘The branch went crunch.’ (lit.)) c. Eda-ga bokiQ-to ore-te i-ta. (VC)

branch-NOM MIM-QUOT break-CONJ be-PST

‘The branch was completely broken.’

Next, Table 3 shows the mimetics that are compatible with the PC-type resultatives.

Table 3 PC-type mimetic resultatives

Suffixal (-QUOT) Emphatic ((-QUOT))

Reduplicative

(unaccented) (-COP) Meaning V

kariQ (MA/PC) n/a karikari ‘crunchy’ yak- ‘fry’

kasaQ (MA/?PC) n/a kasakasa ‘dry and rough’ kawak- ‘get dry’ katiQ (MA/?PC) #kaQtiri katikati ‘solid’ koor- ‘freeze’

paN (MA/*PC) n/a paNpaN ‘inflated’ hukuram- ‘swell’

pariQ (MA/PC) n/a paripari ‘crispy’ kawakas- ‘make dry’

puyoQ (MA/??PC) n/a puyopuyo ‘jelly-like’ hutor- ‘get fat’ sakuQ (MA/PC) ?saQkuri sakusaku ‘crunchy’ age- ‘deep-fry’ saraQ (MA/PC) n/a sarasara ‘dry and smooth’ kawak- ‘get dry’

As was evident in (5b), both reduplicative and suffixal forms, although less productive, can be found in this type of mimetic resultative. The resultative reading of suffixal mimetics is not blocked this time, as their manner reading is not available unless the predicate is replaced by another verb that predicates a prospective event (typically a contact event that makes a sound), as in (7).

(7) Mary-ga beekon-o kariQ-to kan-da. (MA; cf. (5b)) Mary-NOM bacon-ACC MIM-QUOT bite-PST

‘Mary bit the bacon with a crunch.’

Moreover, unlike VC resultatives, PC resultatives almost never accept emphatic mimetic forms (i.e., CVCCVri), as exemplified in (8).

(8) Mary-ga mikan-o {*kaQtiri(-to)/ katikati-ni} koor-ase-ta. (PC) Mary-NOM orange-ACC MIM-QUOT MIM-COP freeze-CAUS-PST

‘Mary froze the orange solid.’

This contrast between VC and PC may stem from the holistic event depiction of emphatic mimetics, which may denote both the manner and result (Akita (2011); Usuki and Akita (2012)). As we will discuss in detail in Section 4, fictive events in VC, but not in PC, are part of the (causative) change-of-state/location event that the predicate describes. Therefore, the whole event matrix that is presupposed and represented by VC resultatives stays within the realm of the holistic semantics of the emphatic mimetics, whereas that of PC resultatives goes beyond this realm.

This observation offers a glimpse into the fundamental difference between the two types of fictivity. In the next section, we will discuss the issue in the theoretical context of Generative Lexicon, which will cast light on the lexical origin of the functional distribution of the mimetic resultatives.

4. A Generative Lexicon Account 4.1. Qualia Structure

In the Generative Lexicon theory (Pustejovsky (1995)), the encyclopedic meaning of each lexical item is described in terms of the four roles in qualia structure, as summarized in (9).

(9) CONST(ITUTIVE): the relation between an object and its constituent parts;

FORMAL: that which distinguishes it within a larger domain;

TELIC: its purpose and function;

AGENT(IVE): factors involved in its origin or “bringing it about.”

(Pustejovsky (1995: 76)) The original version of Generative Lexicon employed qualia structure mainly for nouns.5 More recent work regarding this theory, as well as its neighboring theories, has extended this rich semantic description to accommodate verb semantics. Notably, Kageyama (2005) incorporated his lexical-conceptual structure (or LCS) in the qualia of verbs. The current study is an attempt to further develop this framework to include mimetic lexemes, which are generally characterized by their specific semantic content (Kita (1997); Akita (2012); inter alia). Next, we will demonstrate that qualia structure straightforwardly accounts for the

distributional difference between the two types of fictive mimetic resultatives that were discussed in Section 3.

We propose a highly specific qualia structure for each mimetic. Mimetic qualia are assumed to inherit a large amount of information from verb qualia, as the major function of mimetics is to enrich the event description outlined by their host predicate (Akita (2012)). Extending Kageyama’s (2005) qualia structure of verbs, which is shown in (10a), we posit (10b) as the qualia structure of mimetics.

(10) a. Verb qualia (adapted from Kageyama (2005: 83-84)):

CONST: LCS;

FORMAL: event type (activity, state, process, or transition);

TELIC: its purpose and function;

AGENT: factors involved in its origin or “bringing it about.” b. Mimetic qualia:

CONST: LCS;

FORMAL: aspectuality (punctuality, dynamicity, telicity);

TELIC: its purpose and function;

AGENT: factors involved in its origin or “bringing it about.”

The idealized eventuality that is evoked by mimetics is classified in LCS as the constitutive role (see Kageyama (2007) for a lexico-conceptual approach to mimetic verbs). Although morphological templates of mimetics are iconically paired with a set of aspectual features, many of them are not fully specified with regard to their eventuality types (Kita (1997); Hamano (1998); Akita (2009: Ch. 5)). This semantic characteristic is reflected in the formal role description. The telic role is left unspecified, at least in the present paper, whereas it is specified by unification with verb qualia. Of particular relevance to the current discussion of fictivity is the agentive role, which may even accommodate a fictive event that has caused or is expected to cause the referent state.

4.2. VC-Type Mimetic Resultatives

We will start by discussing the mimetics found in VC-type resultatives. As mentioned in Section 3, fictive events in VC can be viewed as a causing subevent of the (causative) change-of-state/location event that is denoted by the predicate. For example, the branch-breaking event that is vestigially evoked by the snapping sound that the mimetics boQkiri and bokiboki in (5a) mimic is a direct factor of the completely broken state of the branch that is represented by the predicate. This information is described in the agentive

role of these mimetics, as shown in (11). (11) a. boQkiri (emphatic)

CONST = [[x ACT<FORCEFULLY> ON y] CONTROL

[y BECOME [y BE AT COMPLETELY-BROKEN] & EMIT<CRUNCH>]]

FORMAL = ±dynamic

TELIC = […]

AGENT = break(e,x,y)

b. bokiboki (unaccented-reduplicative)

CONST = [y BE AT COMPLETELY-BROKEN] FORMAL = –punctual, –dynamic, –telic (i.e., state)

TELIC = […]

AGENT = break(e,x,y)

These qualia structures are unified (or “co-composed”) with the qualia of the verb or- ‘break’ in (12), which successfully yields the resultative expressions in (5a). Concretely, the verb supplies the causative change-of-state event structure that corresponds to the agentive role of the mimetics, which qualifies them as resultatives that further specify the result state that is denoted by the verb.

(12) or- ‘break’

CONST = [[x ACT ON y] CONTROL [y BECOME [y BE AT BROKEN]]]

FORMAL = transition

TELIC = break(e,y)

AGENT = not-break(x,y)

The same is not true for the suffixal mimetic bokiQ in (6a), which is not interpreted as a resultative phrase. A manner reading has priority in this mimetic because its formal role is specified as “+dynamic” (cf. the formal roles in (11)). The (coerced) state reading in (6c) is attributed to the stative -te i- construction to which the mimetic belongs (see Tsujimura 2002).

(13) bokiQ (suffixal)

CONST = [[x ACT<FORCEFULLY> ON y] CONTROL

[y BECOME [y BE AT COMPLETELY-BROKEN] & EMIT<CRUNCH>]]

FORMAL = +punctual, +dynamic

TELIC = […]

AGENT = break(e,x,y)

4.3. PC-Type Mimetic Resultatives

Mimetics in the PC-type resultatives can be explained in a similar way but with a critical difference. The crunching sound that is imitated by kariQ and karikari in (5b) is neither inherent nor central to the hard, dry texture of the bacon, which one cannot feel without biting it. Similar to the causing subevent in the VC-type cases, the fictive biting activity belongs to the agentive role of the mimetics.

(14) a. kariQ (suffixal)

CONST = [[x ACT ON y<CRUNCHY>] CAUSE [y<CRUNCHY> EMIT<CRUNCH>]]

FORMAL = +punctual, +dynamic

TELIC = […]

AGENT = bite(e,x,y)

b. karikari (unaccented-reduplicative)

CONST = [y BE AT CRUNCHY]

FORMAL = –punctual, –dynamic, –telic (i.e., state)

TELIC = […]

AGENT = bite(e,x,y)

When these mimetic qualia are unified with the verbal qualia in (15), the agentive role of the mimetics is associated with the telic role of the verb (i.e., we fry food to eat it). The eating activity involves biting the food, which causes the sound and feeling that are expressed by the mimetics. This relation between the mimetics and the verb allows the state part of the constitutive role of the mimetics to be co-composed with the ACT ON semantics of the verb, yielding a well-formed resultative expression.

(15) yak- ‘fry’

CONST = [x ACT ON y]

FORMAL = process

TELIC = eat(e,x,y)

AGENT = not-fry(x,y)

The present qualia-structural account is also compatible with the near absence of emphatic mimetics in the PC-type resultatives. The agentive role of the emphatic mimetics, such as boQkiri in (11a), primarily designates a change-of-state event as the cause of the result state that they represent. This semantic specification is likely to clash with the telic specification of the verb, which prefers a simple activity. However, explanations along these lines are

confronted with difficulties due to a few of the cases presented in Table 3. For instance, the telic role of the verb koor- ‘freeze’ appears empty because the event is a natural phenomenon. Accordingly, the agentive role of the mimetic katikati ‘solid’ (i.e., hit(e,x,y)) cannot find its home in the verb qualia. Therefore, a proper generalization would be that the agentive role of the mimetic qualia introduces an additional event that may be identical with or closely related to the verbal telic role.

The present discussion leads us to conclude that PC-type mimetic resultatives are special. In fact, it is likely that PC, but not VC, is unique to mimetics. As shown in (16), we can readily construct VC expressions, but not PC expressions, with non-mimetic items. Moreover, the related literature appears to provide no single non-mimetic example that unambiguously illustrates PC (see Nakamoto et al. (2004)).

(16) a. Takusan-no iwa-ga korogat-te i-ta. (VC) a.lot-GEN rock-NOM roll-CONJ be-PST

‘There lay many rocks.’ (‘Many rocks have rolled.’ (lit.)) b. *Mary-ga beekon-o urusaku yai-ta. (PC) Mary-NOM bacon-ACC noisy fry-PST

‘Mary fried the bacon noisy.’ (lit.)

The uniqueness of the mimetics in PC may come from their semantic peculiarity. As discussed previously, mimetics are characterized by their rich holistic meanings (Akita (2012)). They explicitly or implicitly evoke various aspects of an eventuality (Kita (1997)). For example, the mimetic sugosugo is more than just a manner-of-motion expression for quick, quiet walking steps, as it also suggests the path of motion (i.e., out of others’ sight) and the psychological state of the walker (i.e., embarrassed). This level of richness in the semantics is likely to reside in the relatively free and flexible fictive conceptualizations and metonymical extensions theoretically described previously. Put differently, the present observation seems to exemplify the grammatical relevance of such encyclopedic meaning.

5. Concluding Remarks

In this paper, we proposed a Generative Lexicon account for Japanese mimetic resultatives, in which two types of fictivity play a critical role. The behavioral difference between the VC- and PC-type fictivities can be captured by the agentive role of the relevant mimetics and its co-compositional relation to the verb. The exceptional presence of PC expressions in mimetic resultatives may be derived from the holistic nature of mimetic semantics. Also interesting is the finding that the agentive and telic roles, which are

assumed to be less central to the meanings of mimetics and verbs (see Kageyama (2005)), crucially contribute to the metonymical extensions that underlie fictive mimetic expressions.

The present study has demonstrated the significance of an encyclopedic view of the grammatical consideration of mimetic words, which typically have highly specific meanings. Future research has to find the limits of the semantic abundance. Notably, our observations suggest that mimetic qualia are not highly specified in every aspect (recall the empty telic roles discussed previously). This issue leads us back to the traditional question regarding the semantic and syntactic relationships between mimetics and their collocates, especially for verbs (Akita (2012); Usuki and Akita (2013)). We hope that the current exploration of fictive mimetic resultatives offers a “real” clue regarding this new direction of research.

Notes

* A related paper was presented at the 22nd Japanese/Korean Linguistics Conference (Usuki and Akita (2012)). We are grateful to the participants from this conference for their insightful comments. We also thank Kiyoko Toratani for her constant advice and encouragement regarding this research project. Remaining shortcomings are, of course, our own. This study was partly supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (no. 24720179) and a Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation grant for “Fundamental Investigation” projects (#FEI2010-14903) to the second author.

1 The abbreviations and symbols used in this paper are as follows: ACC = accusative; C = consonant; CAUS = causative; CONJ = conjunctive; COP = copula; DAT = dative; GEN = genitive; MA = manner-adverbial; MIM = mimetic; N = moraic nasal (only for mimetics);

NOM = nominative; NPST = nonpast; PC = prospective cognition; PST = past; Q = geminate (only for mimetics); QUOT = quotative; TOP = topic; V = vowel; VC = vestigial cognition.

2 Copulative mimetics generally represent an extreme state (Toratani (2013)).

3 The emphatic template is incompatible with mimetic roots with C2 /r/ (e.g., *biNriri) (Nasu (2002)).

4 The obligatory presence of the quotative particle may contribute to the priority of the manner interpretation in suffixal mimetics (see (2) for the most typical form-meaning correspondences in Japanese mimetics).

5 The qualia structure of the English noun book, for example, looks like (i):

(i) book

information·phys_obj_lcp

FORMAL = hold(y,x)

TELIC = read(e,w,x.y)

AGENT = write(e’,v,x.y)

(Pustejovsky (1995: 101)) The formal role specifies that a book, which is a physical object, contains information, and the content of the valuables is specified in the argument structure. The telic role denotes that a book is something to be read, and the agentive role designates that a book is created by a writing activity.

References

Akita, Kimi (2009) A Grammar of Sound-Symbolic Words in Japanese: Theoretical Approaches to Iconic and Lexical Properties of Mimetics, Doctoral dissertation, Kobe University.

Akita, Kimi (2011) “A Constructionist Analysis of Emphatic Mimetics in Japanese,” KLS 31: Proceedings of the 35th Annual Meeting of the Kansai Linguistic Society, 240-251.

Akita, Kimi (2012) “Toward a Frame-Semantic Definition of Sound-Symbolic Words: A Collocational Analysis of Japanese Mimetics,” Cognitive Linguistics 23, 67-90.

Hamano, Shoko (1998) The Sound-Symbolic System of Japanese, CSLI Publications, Stanford.

Kageyama, Taro (2005) “Zisyo-teki-Tisiki-to Goyooron-teki-Tisiki: Goi-Gainen-Koozoo-to Kuoria-Koozoo-no Yuugoo-ni Mukete (Lexical Knowledge and Pragmatic Knowledge: Toward the Integration of Lexical Conceptual Structure and Qualia Structure),” Lexicon Forum 1, ed. by Taro Kageyama, 65-101, Hituzi Syobo, Tokyo.

Kageyama, Taro (2007) “Explorations in the Conceptual Semantics of Mimetic Verbs,” Current Issues in the History and Structure of Japanese, ed. by Bjarke Frellesvig, Masayoshi Shibatani, and John Charles Smith, 27-82, Kurosio Publishers, Tokyo.

Kita, Sotaro (1997) “Two-Dimensional Semantic Analysis of Japanese Mimetics,” Linguistics 35, 379-415.

Mikami, Kyoko (2006) “Nihongo-no Giongo/Gitaigo-ni okeru Imi-no Kakutyoo: Konseki-teki-Ninti/Yoki-teki-Ninti-no Kanten-kara (Semantic Extension in Japanese

Mimetics: From the Perspectives of Vestigial/Prospective Cognition),” Studies on Japanese Language and Literature 57, 199-217.

Nakamoto, Koichiro, Katsunori Kotani, and Hitoshi Isahara (2004) “Yoki-teki-Ninti-to Keiyoo-Hyoogen: Huan-ni Motozuku Zyookyoo-Haaku (Prospective Cognition and Interpretation of Adjectives),” Proceedings of the 4th Annual Meeting of the Japanese Cognitive Linguistics Association, 34-44.

Nasu, Akio (2002) Nihongo-Onomatope-no Go-Keisei-to Inritu-Koozoo (Word Formation and Prosodic Structure of Japanese Onomatopoeia), Doctoral dissertation, University of Tsukuba.

Pustejovsky, James (1995) The Generative Lexicon, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Talmy, Leonard (1996) “Fictive Motion in Language and ‘Ception,’” Language and Space, ed. by Paul Bloom, Mary A. Peterson, Lynn Nadel, and Merrill F. Garrett, 211-276, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Tamori, Ikuhiro (1984) “Japanese Onomatopoeias: Manner Adverbials vs. Resultative Adverbials,” Journal of Cultural Science 20, 163-178.

Toratani, Kiyoko (2013) “Hukusi-teki-Onomatope-no Tokusyusei: Tagisei/Zisyoosei-kara-no Koosatu (Peculiarity of Adverbial Mimetics: From the Viewpoint of Polysemy and Eventivity),” Onomatope-Kenkyuu-no Syatei: Tikazuku Oto-to Imi (The Range of Studies in Sound Symbolism: Approaching Sound and Meaning), ed. by Kazuko Shinohara and Ryoko Uno, Chapter 5, Hituzi Syobo, Tokyo.

Tsujimura, Natsuko (2002) “A Constructional Approach to Stativity in Japanese,” Studies in Language 25, 601-629.

Usuki, Takeshi, and Kimi Akita (2012) “A Qualia Account of Mimetic Resultatives in Japanese,” Poster presented at the 22nd Japanese/Korean Linguistics Conference, National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics, Tokyo, 12 October 2012. Usuki, Takeshi, and Kimi Akita (2013) “On the Underspecified Syntactic-Categorial Status of

Mimetics: Research History and Beyond,” Paper presented at the 9th International Symposium on Iconicity in Language and Literature, Rikkyo University, Tokyo, 5 May 2013.