PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

This article was downloaded by: [2007-2008-2009 Yonsei University Central Library] On: 4 December 2009Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 769136881] Publisher Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Global Economic Review

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713735143

South Korea's economic reform and its aftermath

Doowon Lee a

a Yonsei University, Korea

To cite this Article Lee, Doowon'South Korea's economic reform and its aftermath', Global Economic Review, 30: 4, 23 — 50

To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/12265080108449832 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/12265080108449832

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

SOUTH KOREA'S ECONOMIC REFORM

AND ITS AFTERMATH

Doowon Lee Yonsei University, Korea

This paper analyzes the process of Korea's recovery from the 1997 financial crisis with several policy implications. The driving force behind the better-than-expected economic recovery was the reform measures introduced by the Korean government in four major areas such as the financial, corporate, labor and public sectors. Also, Korea's strong export performance helped by the booming U.S. economy provided a favorable external condition for recoveiy. Internally, surging investment in the IT and venture industries, which was deliberately fostered by the government, along with the revived consumption level, enabled the rapid recovery. However, as the U.S. economy slowed and the technology bubble burst in 2000, the Korean economy went through a mild recession in 2001. Based on the experiences of crisis and recovery, the implication of macroeconomic fundamentals is re-examined. Even though the strong macroeconomic fundamentals were misleading in preventing the crisis, they later facilitated the Korean economy's recoveiy. As a result of various reform measures, the Korean economy as of today is in a different environment First, the low investment rate along with the decreased saving rate will marie the end of the high growth era. Second, the substantial deterioration of income distribution will be the major task to be tackled with in the future. Third, the Korean economy is now fully liberalized both in the commodity and capital markets with some side effects and merits. Fourth, the loan and deposit structure of the financial sector is significantly altered. Lastly, more fiscal burden is placed on the shoulders of the government due to the heavy debt service burden of public funds and the generous expansion of social welfare programs.

1. INTRODUCTION

For the past four years after the financial crisis, numerous changes have occurred in the Korean economy. First, there had been a big chaos of massive bankruptcies and mounting unemployment immediately after the meltdown of the financial system, which was followed by the sharp reduction of GDP in 1998. However, to

24 Doowon Lee

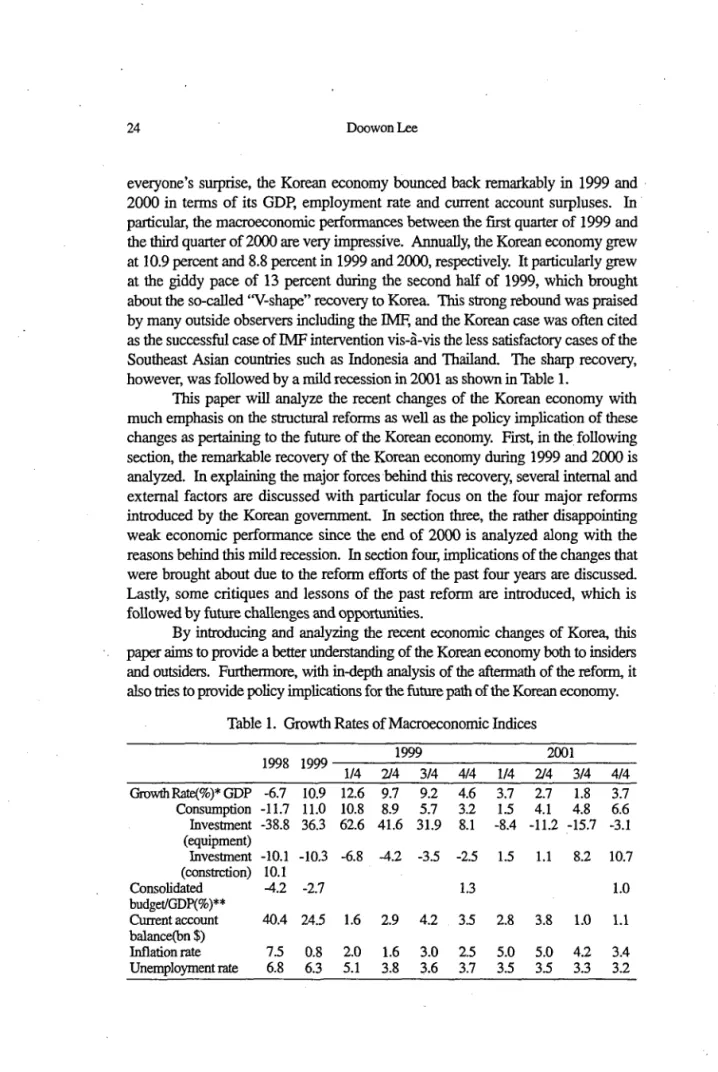

everyone's surprise, the Korean economy bounced back remarkably in 1999 and 2000 in terms of its GDP, employment rate and current account surpluses. In particular, the macroeconomic performances between the first quarter of 1999 and the third quarter of 2000 are very impressive. Annually, the Korean economy grew at 10.9 percent and 8.8 percent in 1999 and 2000, respectively. It particularly grew at the giddy pace of 13 percent during the second half of 1999, which brought about the so-called "V-shape" recovery to Korea. This strong rebound was praised by many outside observers including the IMF, and the Korean case was often cited as the successful case of IMF intervention vis-a-vis the less satisfactory cases of the Southeast Asian countries such as Indonesia and Thailand. The sharp recovery, however, was followed by a mild recession in 2001 as shown in Table 1.

This paper will analyze the recent changes of the Korean economy with much emphasis on the structural reforms as well as the policy implication of these changes as pertaining to the future of the Korean economy. First, in the following section, the remarkable recovery of the Korean economy during 1999 and 2000 is analyzed. In explaining the major forces behind this recovery, several internal and external factors are discussed with particular focus on the four major reforms introduced by the Korean government In section three, the rather disappointing weak economic performance since the end of 2000 is analyzed along with the reasons behind this mild recession. In section four, implications of the changes that were brought about due to the reform efforts of the past four years are discussed. Lastly, some critiques and lessons of the past reform are introduced, which is followed by future challenges and opportunities.

By introducing and analyzing the recent economic changes of Korea, this paper aims to provide a better understanding of the Korean economy both to insiders and outsiders. Furthermore, with in-depth analysis of the aftermath of the reform, it also tries to provide policy implications for the future path of the Korean economy.

Table 1. Growth Rates of Macroeconomic Indices

Growth Rate(%)* GDP Consumption Investment (equipment) Investment (constrction) Consolidated budget/GDP(%)** Current account balance(bn $) Inflation rate Unemployment rate

1QQQiyyo

-6.7 -11.7 -38.8 -10.1 10.1 -4.2 40.4 7.5 6.8

199 10.9 11.0 36.3 -10.3 -2.7 24.5 0.8 6.3

1/4 12.6 10.8 62.6 -6.8

1.6 2.0 5.1

1999 2/4 9.7 8.9 41.6 -4.2

2.9 1.6 3.8

3/4 9.2 5.7 31.9 -3.5

4.2 3.0 3.6

4/4 4.6 3.2 8.1 -2.5

1.3 3.5 2.5 3.7

1/4 3.7 1.5 -8.4 1.5

2.8 5.0 3.5

2001 2/4 2.7 4.1 -11.2

1.1

3.8 5.0 3.5

3/4 1.8 4.8 -15.7

8.2

1.0 4.2 3.3

4/4 3.7 6.6 -3.1 10.7 1.0 1.1 3.4 3.2

Note: * The growth rates are compared to the same quarter of the previous year.

** Figures for 2000 and 2001 are annual figures.

Sources: Major Indicators of the Korean Economy, Korea Development Institute, March 9, 2002:41; Bank of Korea website ("www.bok.or.kr)

2. SUMMARY OF ECONOMIC REFORMS AND REBOUND OF THE KOREAN ECONOMY: 1998-2000

After the outbreak of the financial crisis, the Korean economy began to bounce back. This strong rebound was mostly due to the four major reforms undertaken by the Korean government under the guidance of the IMF with the unprecedented cooperation of business and labor leaders. Thanks to the series of reforms introduced mostly in 1998 and 1999, the Korean economy has undergone major structural changes during the last several years. However, in addition to these structural reform measures, there were several other internal and external factors that made the rebound possible.

Four Major Reforms

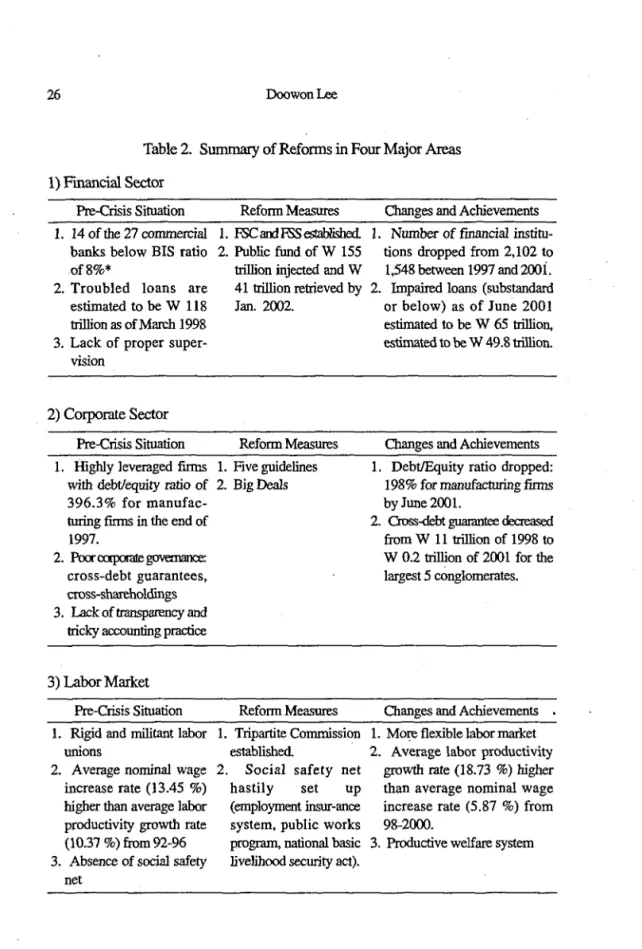

The strong rebound was accompanied by a stable inflation rate and a decrease in the unemployment rate. There are several causes behind this better-than-expected recovery. Lee (2000) stated that, a series of painful structural reforms, which were introduced mostly in 1998 and 1999, was one of the major factors for the successful performance. In particular, the financial sector regained its financial soundness after the government-led consolidations and liquidations proved to be successful with the injection of public funds. As a result, the corporate sector could lower its debt-equity ratio substantially. Also, many measures to improve the transparency of the corporate governance system were put in place. Unquestionably, it was the labor market that embraced more changes than any other sector during this period. It has become much more flexible, and its structure has changed with less full time employment and more part time. According to Lee (2001), the labor market flexibility measured by Okun's law coefficient was enhanced after the crisis.1 It shows that the labor market responded more actively to the fluctuation of economic growth rates' change after the crisis than before.2 In addition, the public sector went through the processes of deregulation and privatization. Table 2 summarizes the achievements of the past four years.

26 DoowonLee

Table 2. Summary of Reforms in Four Major Areas 1) Financial Sector

Pre-Crisis Situation Reform Measures Changes and Achievements 1. 14 of the 27 commercial

banks below BIS ratio of8%*

2. Troubled loans are estimated to be W 118 trillion as of March 1998 3. Lack of proper super-

vision

1. FSC and FSS established. 1. Number of financial institu- 2. Public fund of W 155 tions dropped from 2,102 to trillion injected and W 1,548 between 1997 and 2001. 41 trillion retrieved by 2. Impaired loans (substandard Jan. 2002. or below) as of June 2001 estimated to be W 65 trillion, estimated to be W 49.8 trillion.

2) Corporate Sector

Pre-Crisis Situation Reform Measures Changes and Achievements 1. Highly leveraged firms 1. Rve guidelines

with debt/equity ratio of 2. Big Deals 396.3% for manufac-

turing firms in the end of 1997.

2. Poor corporate governance: cross-debt guarantees, cross-shareholdings 3. Lack of transparency and

tricky accounting practice

1. Debt/Equity ratio dropped: 198% for manufacturing firms by June 2001.

2. Cross-debt guarantee decreased from W 11 trillion of 1998 to W 0.2 trillion of 2001 for the largest 5 conglomerates.

3) Labor Market

Pre-Crisis Situation Reform Measures Changes and Achievements 1. Rigid and militant labor

unions

2. Average nominal wage increase rate (13.45 %) higher than average labor productivity growth rate (10.37%) from 92-96 3. Absence of social safety

net

1. Tripartite Commission established.

2. Social safety net hastily set up (employment insur-ance system, public works program, national basic livelihood security act).

1. More flexible labor market 2. Average labor productivity

growth rate (18.73 %) higher than average nominal wage increase rate (5.87 %) from 98-2000.

3. Productive welfare system

4) Government Sector

Pre-Crisis Situation Reform Measures Changes and Achievements 1. Regulation 1. Administrative reform 1. Approximately 143,000 emp- 2. Inefficient public enterprises 2. Deregulation loyees were laid, off from the 3. Privatization public sector between 1998

and 2001.

2. Number of regulations decreased from 10,717 of August 1998 to 7,156 of July 2001. 3. Privatized 6 public enterprises

and plans to privatize 5 more as of January 2001.

Note: * BIS (Bank for International Settlements) ratio measures the ratio of bank's equity over a weighted average of risky assets. The higher this ratio is, the more financially sound is the bank.

Sources: Bank of Korea website (www.bok.or.kr): Korea Financial Supervisory Commission website (www.fss.or.kr): Korea National Statistical Office website (www.nso.go.kr1: Korea Development Institute website (www.kdi.re.kr): Fair Trade Commission website (www.ftc.go.kr)

Reform measures of the financial, corporate, labor, and public sectors and their influence on the Korean economic structure are analyzed in the following paragraphs.

Financial sector

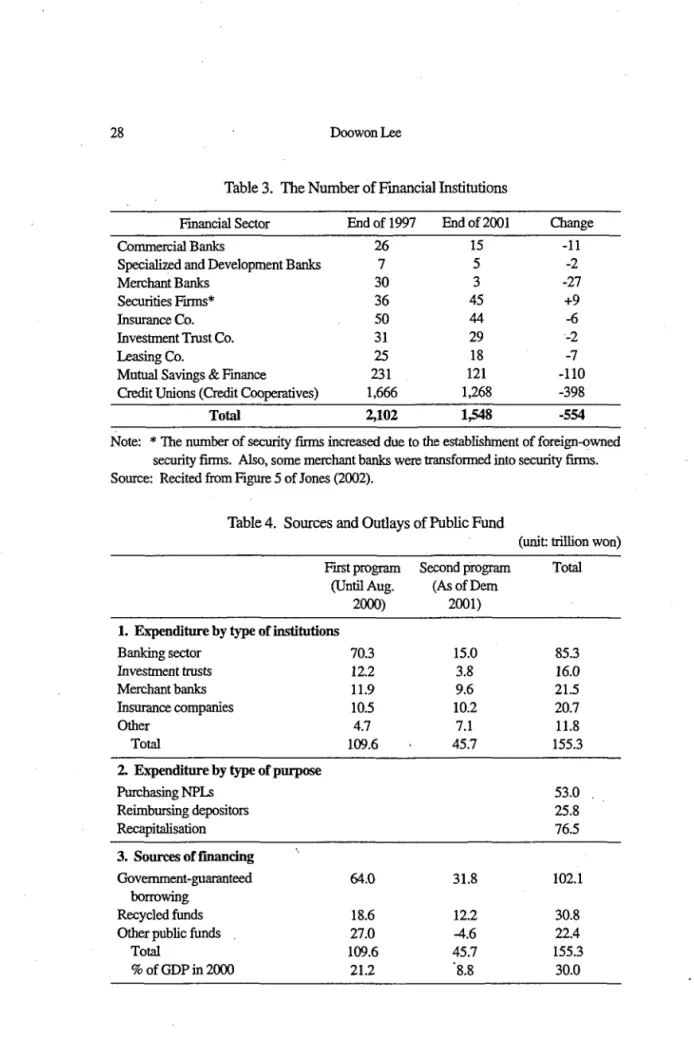

The omni-powered Financial Supervisory Commission (FSC), an independent and unified body covering banking, insurance, non-banks and the capital market, was first established. Upon its establishment, the FSC began to address the problems of non-performing loans (NPLs) and the under-capitalization of financial institutions through two rounds of financial sector restructuring. Following the leadership and guidelines of the FSC, the Korean financial sector underwent restructuring with numerous financial institutions either being shut down or consolidated. Also, slightly more than 1/3 of employees in the commercial banking sector lost their jobs. In the mean time, an astrological amount of the so-called "public fund" was injected into the financial sector in order to remove the non-performing loans and to re-capitalize the remaining financial institutions. The number of financial institutions before and after the crisis and the usage of the public fund are summarized in the following tables.

28 Doowon Lee

Table 3. The Number of Financial Institutions Financial Sector

Commercial Banks

Specialized and Development Banks Merchant Banks

Securities Firms* Insurance Co. Investment Trust Co. Leasing Co.

Mutual Savings & Finance Credit Unions (Credit Cooperatives)

Total

End of 1997 26

7 30 36 50 31 25 231 1,666 2,102

End of 2001 15

5 3 45 44 29 18 121 1,268 1,548

Change -11

-2 -27 +9 -6 -2 -7 -110 -398 -554 Note: * The number of security firms increased due to the establishment of foreign-owned

security firms. Also, some merchant banks were transformed into security firms. Source: Recited from Figure 5 of Jones (2002).

Table 4. Sources and Outlays of Public Fund

(unit: trillion won) First program

(Until Aug. 2000) 1. Expenditure by type of institutions Banking sector

Investment trusts Merchant banks Insurance companies Other

Total

70.3 12.2 11.9 10.5 4.7 109.6 2. Expenditure by type of purpose

Purchasing NPLs Reimbursing depositors Recapitalisation 3. Sources of financing Government-guaranteed

borrowing Recycled funds Other public funds

Total

% of GDP in 2000

64.0 18.6 27.0 109.6

21.2

Second program (As of Dem

2001)

15.0 3.8 9.6 10.2

7.1 45.7

31.8 12.2 -4.6 45.7 '8.8

Total

85.3 16.0 21.5 20.7 11.8 155.3

53.0 25.8 76.5

102.1 30.8 22.4 155.3

30.0

4. Net outlays

Total minus recycled funds

% of GDP in 2000

91.0 17.6

33.5 6.5

124.5 24.1 Sources: Recited from Figure 6 of Jones (2002).

SERI (in Korean, February 2002).

In dealing with the NPLs of the financial institutions, the Korea Asset Management Company (KAMCO) and the Korean Deposit Insurance Corporation (KDIC) played a major implementation role. By the end of 2001, KAMCO purchased around 100 trillion won of impaired assets from the troubled financial institutions, and KDIC re-capitalized weak financial institutions and reimbursed depositors.

As a result of this harsh restructuring effort, many structural changes and improvements were made in the financial sector. Many commercial banks were de facto nationalized after the recapitalization scheme of the government, and the surviving banks had to pursue mergers in order to enhance their profitability. In particular, the banking sector could greatly improve its financial soundness, as reflected in their BIS ratios and NPL/total loan ratios. As shown in the following table, the average BIS ratio is currently well above the target ratio of 8 percent and the amount of NPLs has been drastically reduced.

Table 5. Financial Soundness of Commercial Banks

(unit: %, trillion won)

BIS ratio NPL/Total Loans ratio NPL

1997 7.0 6.0 22.7

1998 8.2 7.4 21.2

1999* 10.8 13.6 44.5

2000 10.8

8.9 32.0

Sep. 2001 10.7

3.8 14.1 Note: * Following the international standard, Korea has adopted the forward-looking

criteria (FLC) in defining NPL since the end of 1999. The ratio of NPL to total loans increased after the adoption.

Source: Recited from Table 4 of Choi and Noh (in Korean, 2002).

Not only did the overall financial strength improve, but the structure of loans and deposits also changed as well. Compared to the pre-crisis structures, the bank loans are tailored more toward households, which are deemed to be more safe and profitable.3 Also, due to the effort of savers to seek for a safe haven, the banking sector has attracted a relatively larger share of deposits compared to other financial institutions.

Thanks to these reform measures, the financial soundness and profitability

30 DoowonLee

of Korean banks have greatly improved. However, even after the series of reform efforts, the amount of the non-performing loans is still formidable in the overall financial sector including the non-bank financial institutions. According to the FSS (Financial Supervisory Service) of Korea, the ratios of non-performing loan out of the total loans made by financial institutions were 14.9 percent in the end of 1999 and 13.6 percent as of June 2000. This figure is substantially higher than countries such as Taiwan, the U.S., and most of the European countries. For example, in the case of the U.S., the ratio of the non-performing loans out of the total loans made by the ten biggest commercial banks in 2000 was merely 1.2 percent, which is almost negligible compared to those of Korea and Japan.4

Corporate sector

According to the original agreement between the Korean government and the IMF, five guidelines were proposed to make the corporate sector more competitive and transparent. They were to improve management transparency, abolish cross-debt guarantees, restructure capital structure, concentrate on core businesses, and enforce management responsibility. In sum, these five guidelines can be boiled down to the following two broad categories. One is to improve the corporate sector's financial health, and the other is to improve the corporate governance system. Achievement of these two broad goals was expected to prevent the reckless expansion of corporate investment into unprofitable projects.

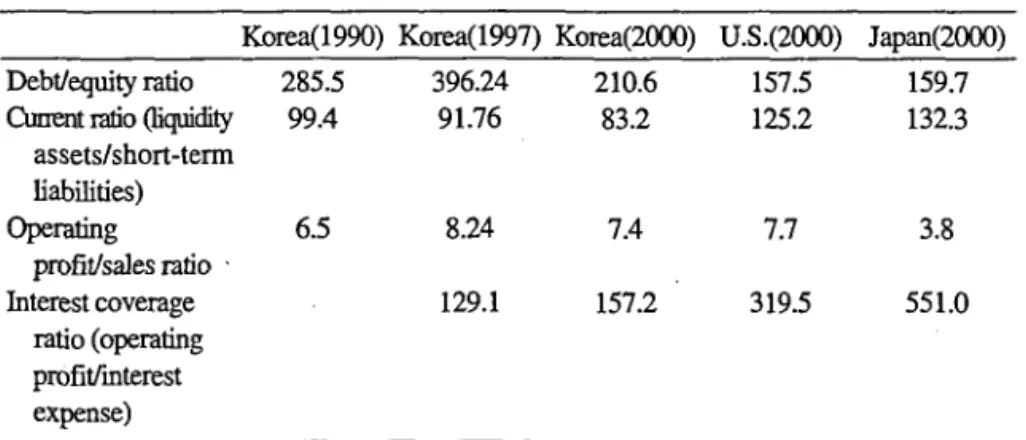

First, let us examine the financial structure of the Korean companies after the crisis. It was a well-known fact that the debt-ridden Korean companies had to sacrifice its profits due to the heavy burden of serving its debt According to Jones (2002), the debt/equity ratio for the top 30 chaebols in 1997 was 519 percent, and the burden of debt service accounted for 17 percent of total business costs for these conglomerates. Due to this high debt service burden, about 44 percent of the listed firms' interest coverage ratio (ICR) was less than one in 1999. Therefore, one of the immediate concerns was to reduce this high debt/equity ratio. Even though there was a controversial debate whether it would be appropriate to apply a unilateral criteria of the 200 percent debt/equity ratio to every industry, the Korean government insisted on applying this ratio to every industry and virtually to every firm. To many financially distressed Korean firms, achieving the 200 percent debt/ratio the middle of a severe credit crunch was a grueling job. In the end, only 18 conglomerates out of the 30 conglomerates listed in 1997 remained listed in the Korean stock market by 2001. Eventually, as shown in the following table, the Korean companies' average debt/equity ratio went down to the targeted rate of 200 percent by 2000.

Table 6. International Comparison of Business Performance for Manufacturing Industry

Debt/equity ratio Current ratio (liquidity

assets/short-term liabilities) Operating

profit/sales ratio Interest coverage

ratio (operating profit/interest expense)

Korea(1990) 285.5

99.4

6.5

Korea(1997) 396.24

91.76

8.24 129.1

Korea(2000) 210.6

83.2

7.4 157.2

U.S.(2000) 157.5 125.2

7.7 319.5

Japan(2000) 159.7 132.3

3.8 551.0

Source: Bank of Korea (in Korean, March 11,2002)

However, the reduction of the debt/equity ratio was not truly because of the reduction of debt, but rather because of the increase in equity due to the money from the booming stock market. During the period of 1997 to 1999, the total amount of debt for the largest 30 conglomerates excluding Daewoo was reduced from W 307.4 trillion to W 243.9 trillion. During the same period, however, the net worth of the largest 30 conglomerates rose from W 62.9 trillion to W 148.8 trillion.6 This unsatisfactory result of debt reduction can explain why the debt service burden of the Korean firms, measured by the amount of interest expenses out of total sales, has not decreased to the level of rivaling economies such as Japan and Taiwan.7

Figure. 1 Debt Service Burden of Manufacture Co.

J I 1

Ratio of Financial Cost to Sales 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

Source: Bank of Korea- website (www.bok.or.kr1.

Not only did the debt/equity ratio change substantially, but the way Korean firms finance their investments has also changed. While Korean firms relied heavily on indirect financing such as loans from banks before the crisis, now they

32 Doowon Lee

have become more reliant on direct financing methods such as issuing equities, bonds, or CP (corporate papers).

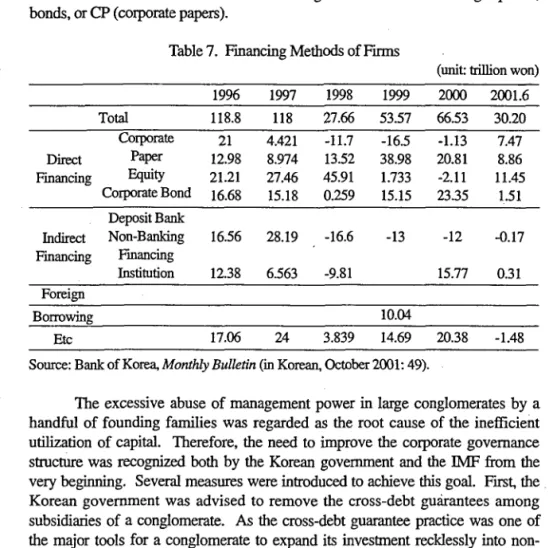

Table 7. Financing Methods of Firms

(unit trillion won)

Direct Financing

Indirect Financing

Foreign Borrowing

Etc

Total Corporate

Paper Equity Corporate Bond

Deposit Bank Non-Banking Financing Institution

1996 118.8 21 12.98 21.21 16.68 16.56 12.38

17.06

1997 118 4.421 8.974 27.46 15.18 28.19 6.563

24

1998 27.66 -11.7 13.52 45.91 0.259 -16.6 -9.81

3.839

1999 53.57 -16.5 38.98 1.733 15.15 -13

10.04 14.69

2000 66.53 -1.13 20.81 -2.11 23.35 -12 15.77

20.38

2001.6 30.20 7.47 8.86 11.45

1.51 -0.17 0.31

-1.48 Source: Bank of Korea, Monthly Bulletin (in Korean, October 2001:49).

The excessive abuse of management power in large conglomerates by a handful of founding families was regarded as the root cause of the inefficient utilization of capital. Therefore, the need to improve the corporate governance structure was recognized both by the Korean government and the IMF from the very beginning. Several measures were introduced to achieve this goal. First, the Korean government was advised to remove the cross-debt guarantees among subsidiaries of a conglomerate. As the cross-debt guarantee practice was one of the major tools for a conglomerate to expand its investment recklessly into non- related business areas, the removal of this old practice was viewed as important. This is the area where the most visible outcome was produced as shown in Table 8. Virtually all of the cross-guaranteed debt by the top 5 conglomerates was removed, and most of the cross-guaranteed debt by the top 30 conglomerates was removed. The removal of this cross-guaranteed debt freed many subsidiaries from the possible threat of chain-reacted bankruptcies as was witnessed in the case of Daewoo's collapse.

Table 8. Reduction of Cross-Guaranteed Debt by the 30 Largest Conglomerates (unit: trillion won) 30 Largest conglomerates Top 5 Conglomerates 6th to 30th

Conglomerates Cross-

Guaranteed Debt Subject

To Reduction

Cross- Guaranteed

Debt Not Subject to Reduction

Cross- Guaranteed

Debt Subject

To Reduction

Cross- Guaranteed

Debt Not Subject to Reduction

Cross- Guaranteed

Debt Subject

To Reduction

Cross- Guaranteed

Debt Not Subject to Reduction April 1,

1998(A) April 1, 1999(B) April 1, 2000(A) April 2, 2001(B)

26.9 9.8

0.5 0.4

36.6 12.6

4.8 4.5

11.1 2.3

0 0.06

18.4 2.7

0.38 0.35

15.8 7.5

0.5 0.3

18.2 9.9

4.4 4.2 Note: The composition of the 30 largest conglomerates varies every year.

Source: Fair Trade Commission.

Another important measure to make the management system more transparent was the introduction of more outside directors to the board of directors, and the strengthening of minority shareholders' rights. Some other measures include the introduction of international accounting standards in 1998, reinforcement of the duties and liabilities of the board of directors, and allowing the establishment of holding companies. Even though it is rather early to judge whether these structural changes have actually changed the management environment in Korea, anecdotal stories provide some evidences of improvement. Labor market

The labor market is probably the place where the impact of the crisis was felt the keenest, especially in the beginning stage of the crisis. The Korean labor market enjoyed de facto full employment for a long time before the crisis. This was due to several factors including the life-time employment practice, continuous job creation during the high growth era and the existence of strong labor unions. All these factors made lay-offs difficult. As a result, the Korean labor market was notoriously rigid.8 Even though this rigid nature of the labor market had been blamed both domestically and internationally for the deterioration of the competitiveness of Korean firms before the crisis, no structural reform was possible. Even though there was a last-minute effort to pass a law that could make

34 Doowon Lee

lay-offs easier at the end of the Kim Young Sam's regime, it failed to pass the National Assembly due to the strong opposition from the then-opposition party of Kim Dae-Jung. Not only was the labor market structure very rigid, but also the growth rate of nominal wages frequently exceeded the growth rate of labor productivity. This inevitably made the unit labor cost of Korea far higher than its competitors.

Analyzing the labor market structure is also very crucial in understanding each country's development model. In many countries, the flexibility of its labor market reflects the development philosophy of its leaders. When there exists a certain degree of a trade-off between efficiency and equity, the efficiency-oriented country tends to emphasize the flexibility of its labor market more than the equity- oriented country. For example, countries such as the U.S., the U.K., and the Netherlands have introduced many measures during the 1980s and 90s that have made labor markets more flexible.9 In large part to these measures, these countries' governments could achieve a lower unemployment rate and spend less on social welfare than other developed countries. On the contrary, countries such as Japan, France and Germany have a relatively rigid labor market, which can explain the stubbornly high unemployment rates in France and Germany and the slow restructuring process of the Japanese economy.

After the outbreak of the crisis, the first task of the Korean government was to establish a "tripartite commission" composed of labor, management and the government. Upon establishing this commission, the Korean government encouraged it "to reach an agreement ers regarding the expediency of layoffs. When many firms were tackling the painful restructuring effort, which inevitably involved massive layoffs, the labor union had no other choice but to accept the agreement reached by the tripartite commission.

Several studies including Kim eL al. (in Korean, 2000), Lim (in Korean, 2000) and Chang & Hahn (in Korean, 1999)have already been made to examine whether the Korean labor market has become truly more flexible after the crisis. Even though they apply different methods of analysis, they all conclude that the Korean labor market has become more flexible after the crisis. More recently, Lee (2001) concluded that the Korean labor market has in fact become more flexible using the calculation of Okun's coefficient.

The flexibility of the labor market can be illustrated by the employment structure as well. As the labor market became more flexible, fewer workers are working full time after the crisis as shown in the following table. Also, according to Lim (in Korean, 2000:32), the increase of part-time laborers in the Korean labor market is highly correlated with the reduction of unit labor cost and the increase of labor productivity in Korea.

Table 9. Employment Structure

(unit: %) Working

Hours Status of

Work

Less than 36 hours/week More than 36 hours/week

Regular Workers Temporary Workers

Daily Workers

1997 7.3 91.8 54.1 31.6 14.3

1998 9.3 89.5 53.0 32.8 14.2

1999 10.5 88.4 48.3 33.4 18.3

2000 9.8 89.2 47.6 34.3 18.1

2001 10.1 88.8 48.7 34.5 16.8 Sources: Kim eL al. (in Korean, 2000:173).

Bank of Korea, Monthly Bulletin (in Korean, July, 2000:32). National Statistical Office Republic of Korea.

However, the flexible labor market with relatively easy layoff practices and less full-time jobs has been challenged by the labor unions. A s shown in the following table, the total number of labor disputes and the resulting workday losses during the last couple of years have significantly increased.

Table 10. Annual Trend in Labor Disputes

Classification 1990 1995 1997 1998 1999 2000 Number of Disputes (cases) ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^

NumberofParticipants m 5Q ^ m ^ m

(thousand persons)

Workdays Lost 4-4 8 7 3 93 445 1,452 1,366 1,894 (thousand days)

Source: Ministry of Labor website (www.molab.go.kr).

National Statistical Office Republic of Korea website (www.nso.go.kr').

Not only was the labor market rigid, but the social safety net was also very limited before the crisis. However, as the unemployment rate soared after the crisis, the social safety net was hastily expanded and modified with a sharp increase of budget expenditures into this area. First, the employment insurance system was expanded so as to cover about three fourths of all employees. The government also poured huge amounts of money into vocational training and public works programs in response to the rising unemployment. Finally, the government introduced the "productive welfare system" in October 2000, which made social assistance a right for those who qualify under the eligibility criteria and ensured that the recipients' income reach the minimum cost of living.10 Public sector reform

The Korean public sector, which is composed of the central government, local

36 Doowon Lee

governments and various public enterprises, had to undergo restructuring and privatization reforms. First, the "deregulation commission" was established, and it abolished nearly half of all the registered regulations during the last three or four years. In order to achieve the slogan of the so-called "small government," the number of the central government's ministries was reduced from 23 to 19. Also, approximately 143 thousand employees were laid off from the public sector from the period of 1998 to 2001. Furthermore, several other administrative reforms such as the performance-based wage system and the filling of high-level government posts with specialists from the private sector to enhance efficiency were introduced. In terms of privatization of the state-owned-enterprises (SOEs), six SOEs such as POSCO and Korea Heavy Industries and Construction Co. have been privatized so far, and five others are under consideration.

Achievement of reforms

Due to these painful reform efforts, the shortage of foreign exchange reserves and the severe BOP imbalance, which triggered the crisis in the first place, have disappeared. As of the end of 2001, Korea's total external liability was US$ 119.9 billion with a short-term liability of only US$ 38.9 billion, while Korea is maintaining the comfortable level of foreign exchange reserves of US$ 102.8 billion." With the improved BOP status and the restructured economy, many international credit rating companies such as Moody's and S&P have upgraded the credit rating of the Korean economy by several notches.12

Now, according to officially released data, Korean financial market has reached the level of the Japanese economy, if not the level of the U.S. and other leading economies, in terms of its financial soundness. Table 10 compares Korea to other leading nations in terms of the relative size of NPLs of commercial banks. As shown in the table, even though the soundness of Korean banks before the crisis was far worse than that of other countries, they are now at least as good as that of Japan.13

Table 11. International Comparison of NPL Korea*

(1997) 6.0

Korea* (1999) 13.6

Korea* (Sep. 2001)

3.8

U.S.** (2000) 1.21

Japan** (2000)

5.44

Germany**

* (1999) 1.3

(unit: %) U.K.** *

(1999) 2.17 Sources: Korea Financial Supervisory Service (www.fss.or.kr).

The Banker (July 2000, July 2001), recited From www.seri.org (June 2001) and www.bok.or.kr.

Note; * Average of all the commercial banks' NPLs.

Korea has changed its criteria of NPLs in 1999 according to the international standard.

** Average of ten biggest commercial banks' NPLs.

*** Average of five biggest commercial banks' NPLs.

Internal and External Factors behind the Rebound

While the above-mentioned structural reforms have contributed to the recovery of the Korean economy in 1999 and 2000, there are other external and internal factors that should also be taken into consideration. The first and foremost important contributing factor was Korea's impressive export performance, driven by the strong demands from the U.S. market. Clearly, the booming U.S. market was the locomotive of the world economic growth in the latter half of the 1990s, and the crisis-hit Asian economies were its biggest beneficiaries.

The second factor, which is related to the first factor, was the role of the booming IT (information technology) and TT-related venture industries in both export and investment performance. The IT industry, which accounted for slightly more than 10 percent of the GDP, contributed roughly 40 to 50 percent of the economic growth, 30 percent of investment and 40 percent of the total exports during the period of 1999 to 2000.14 The comparison between the IT sector and the non-IT sector is particularly vivid in the export performance. The IT industry exports enjoyed rapid growth due to the increased demands from the booming so- called "new economy" sector of the U.S. economy. The IT sector's export grew nearly 10 times faster than the non-IT sector from 1999 to 2000. This unbalanced growth of the IT sector vis-a-vis the non-IT sector, however, has created the problem of bi-polarization of the Korean economy, and has made the Korean export industry highly dependent upon external factors such as the U.S. economic performance.

The other sector that enjoyed a high rate of investment growth was the newly emerged venture industry. The outflow of financial and personnel resources from the existing firms after the crisis along with the strong initiatives taken by the Korean government to develop the IT sector and venture industry helped the booming IT-related venture businesses, and created the Korean version of the new economy. More than 10,000 new venture firms have been created since 1998, and are employing more than 400,000 laborers as of today.15 The sharp increase of equipment investment during 1999 and 2000 as shown in Table 1 was largely due to the booming IT and venture industries.

Thirdly, consumption was revived in 1999 and 2000 after the painful efforts of structural reform and the easing of the credit crunch. As the unemployment rate headed downward since late 1998, disposable income began to increase again along with consumption. Furthermore, consumption was fueled by the low interest policy of the government and the availability of more easy loans from financial institutions.16 Also, the booming stock market generated positive wealth effects, which helped consumption as well. As the KOSPI stock index umped from the bottom of 280 on June 16,1998 to the peak of 1059 on January 4, 2000 as shown in the following figure, consumption was revived partly due to the positive income

38 Doowon Lee

effect of stock price on consumption.17 Also, many firms, particularly the IT and venture firms, found it easier to raise capital in the stock market.

Figure. 2 Stock Index from 1998 to March 2002 1200

1000 800 600 400 200

o

- -

- 1998-01-03

ft-

i

1999-01-03

ht\f\.

V

1

2000-01-03

\ Ax /J*^

i

2001-01-03

y

• W.J

i

2002-01-03 KOSPI

Source: The Korea Stock Exchange (www.kse.or.kr1.

Behind the increased investment and consumption, there was a change of the government policy stance. Despite the initial advice of the IMF, the government policy was switched to an expansionary stance soon after the onset of the crisis. According to Lee and Park (2001), it is presumed that this switch occurred in April 1998, and since then the government has continued to provide fiscal stimulus and monetary liquidity to the market

3. RECENT SLOW-DOWN AND UNFINISHED BUSINESS OF REFORM: 2000-2002

However, since the latter half of 2000, the economic tides have reversed. There were vivid signs of slow down, if not recession, of the economy from as early as the spring of 2000. First, as the investment bubble of the IT and venture sectors burst along with the growing uncertainty in the financial and corporate sector reforms, the stock market began to head downward from early 2000.18 In particular, the collapse of the Daewoo conglomerate in July 1999 triggered the downward trend. The collapse of Daewoo not only hit the stock market hard but also left many investment trust companies, which owned the lion's share of corporate bonds and corporate papers issued by Daewoo, in trouble. Furthermore, negative external factors such as the slow down of the U.S. economic growth, continued recession of the Japanese economy and rising oil prices also inflicted the

Korean economy. In particular, the slow down of the U.S. economy heavily inflicted the Korean export industry, especially the IT industry, as the Korean economy's reliance on exports had increased substantially after the crisis. The slow down of the Korean economic growth has become undeniable as the 4th quarter growth rate of 2000 turned out to be 4.6 percent followed by an even worse figure of 3.7 percent for the 1st quarter of 2001. In particular, the growth rate of GNI, which incorporates the effect of deteriorating terms of trade with the income data, for the 1 st quarter of 2001, was merely 1.1 percent.

As the economic situation deteriorated sharply from the 4th quarter of 2000, economists as well as the Korean government began in retrospect to find out what went wrong. The deterioration of external factors, especially the slow down of the U.S. economy, was largely blamed.19 However, there were internal factors as well. The most important internal factor was the lack of structural reform and the initial under-estimation of the problems prevailing in the financial and corporate sectors. As was emphasized by Lee (2000), the 1997 economic crisis was not a foreign exchange liquidity crisis but a structural one. However, in the process of recovering from the crisis, too much emphasis was given to the provision of monetary liquidity and fiscal stimulus. Relatively speaking, however, structural reform was only hah0 way done, and there still remained the unfinished business of cleaning up the dud loans in Korea's financial sector, in particular in the non-bank financial institutions. Therefore, many economists began to doubt whether the better-than-expected recovery of the Korean economy in 1999 and 2000 was truly a reform-led recovery or merely a liquidity-fueled recovery. The IMF confirms this view as well. In a conference held by the IMF and KDI, Gruenwald (2002) also pointed out that the structural reform has been progressing slower than expected. More specifically, he analyzed that more progress was made in the financial sector than the corporate sector, while the least progress was made in the public sector. However, considering the vast and complicated nature of the reform, he also mentioned that it was understandable.

In the financial sector, there is still a considerable amount of non- performing-loans even after the injection of an astronomical amount of public funds, and several financial institutions such as Seoul Bank and Daehan Life Insurance Co. are still looking for new investors. Also, as a medium- to long-term task for the government, there is the issue of re-privatization of many financial institutions, which have been de facto nationalized in the process of reform.20 hi the corporate sector, the fates of several troubled large companies such as Daewoo Motors, Hyundai Investment Trust and Security Co., and Hynix Semi-conductor Inc. still hinge on the hands of the creditor banks and government. In the short- term, how to deal with these companies will greatly affect the credibility of the government-led reform efforts. Also, as an inevitable result of corporate sector reform, the cross-holding of shares among related companies within a

40 Doowon Lee

conglomerate has either increased or remained unchanged, while the cross-debt guarantees have been virtually abolished.21 In the past, high degrees of cross- holding of shares and cross-debt guarantees among related companies within a conglomerate were the cornerstone of controlling numerous numbers of companies by a single person or a family who actually owns a small number of shares. As the internal cross-holding of shares still remain high within conglomerates, the exertion of management power over related companies by a handful number of people still remain influential. Another mission that has to be tackled with is how to improve the profitability of Korean firms. While the financial soundness of the corporate sector has improved remarkably during the last four years, profitability is still lagging behind that of advanced countries' firms as shown in Table 6. In the labor market, the improved flexibility has left its structure much more vulnerable to external shocks. In the government sector, deregulation and large-scale privatization are still in progress, and there remains the sensitive issue of whether the government will allow large conglomerates to join the bidding for the sales of large public companies and banks.

4. IMPLICATIONS OF REFORM: CRITIQUES, LESSONS AND AFTERMATH

Critiques and Lessons from the Past Reform Experience

Initial optimism and underestimation of the problem

What aggravated the unsatisfactory outcome of reform was the initial underestimation of the problem. Initially, the total amount of troubled loans was estimated to be W 118 trillion, and the injection of the W 64 trillion public fund was thought to be enough. However, as firms began to reveal their real financial situation that had long been concealed through tricky accounting practices, more loans turned out to be in trouble. Eventually, the government asked the National Assembly for the establishment of an additional W 40 trillion public fund, and many skeptics inside and outside the government were even wondering whether there would be no further need of another public fund in the future.22

Li fact, just before the outbreak of the crisis, there was optimistic euphoria praising the strong fundamentals of the Korean economy both inside and outside Korea. In terms of macroeconomic indices such as the growth rate, inflation rate, unemployment rate, budget balance, savings rate and investment rate, the Korean economy's performance until the mid-1990s was almost impeccable. Even though the balance of payment was suffering from the chronic current account deficit, the relative size of the deficit was declining. Due to this macroeconomic strength, many people believed that the Korean economy would be immune to the financial

crises originating in Thailand and Indonesia. However, the sound macroeconomic indices were illusionary. In terms of the microeconomic foundations, the Korean economy was losing its competitiveness rapidly. The export performance was disappointing due to the overvalued exchange rate, and many firms could not cover their interest expenses with their operating profits. Furthermore, most of the Korean conglomerates were highly leveraged. Therefore, the first lesson we learned was how important it is to have a balanced view between macroeconomic and microeconomic indices, and to have a proper capability of predicting and preventing a financial crisis.

Ironically, however, it was the strong macroeconomic fundamentals that made rapid recovery possible. Due to the healthy fiscal status of the Korean government, Korea could rapidly build up a social safety net system. Also, the government could keep the investment rate from falling further by providing fiscal stimulus into construction industries such as social overhead capital.23 Also, the Korean households with high savings and low debt burden soon resumed their consumption, which was another pillar that bolstered recovery. Therefore, even though the macroeconomic fundamentals misled us in terms of crisis-prediction, they clearly helped us in overcoming the post-crisis situation.

Reform fatigue

Not only was the structural reform only half way done, but also the government's appetite for continued reform effort seemed to erode since early 2000. In particular, when the government provided support to troubled giants such as Hyundai Engineering & Construction Co. and Hynix Semiconductor Inc., both saddled with several billion dollars in loans maturing by 2001, through the controversial bond refinancing program, many Korean watchers worried whether the government was retreating from the principle of reform. In particular, after the June 2000 historic summit of South and North Korea, the South Korean President, Kim Dae-Jung, was criticized for being too obsessed with unification issues while neglecting other pressing issues including economic reform.

Also, resistance from the vested interest groups such as conglomerates, public enterprises and labor unions increased as the government loosened up its leashes. For example, the number of labor disputes increased again. In 2000 and 2001, there were 250 and 235 cases of labor disputes with several of very violent strikes in the middle of 2001. Also, more recently, the privatization scheme of public enterprises such as the Korea Electric Power Corporation and the Korea Railroad is facing severe resistance from the labor unions.

Policy overshooting and sequence of reform

Even though most policy makers applauded the general direction of reform, there were controversies about the speed, magnitude and sequence of the reform

42 Doowon Lee

measures. Initially, the IMF prescribed contractionary fiscal and monetary policies in order to stabilize the exchange rate as it did in handling the Latin American crises. However, unlike the Latin American economic crises, which were caused partly by the ballooning fiscal deficit, the Korean economy's fiscal stance was very sound before the crisis. Therefore, many economists blamed the IMF's remedy of suggesting contractionary fiscal policy to Korea without considering its uniqueness. Also, in terms of monetary policy, the initial contractionary monetary policy with n extremely high interest rate was frequently criticized. As Cho (2001) mentioned, the initial IMF high interest policy was responsible for producing unnecessary victims, while the desired effect of stabilizing the exchange rate was minimal.24 The IMF defended its high interest policy in the beginning, claiming that it had a positive effect of stabilizing the exchange rate. However, soon after the outbreak of the crisis, the IMF also agreed to reverse these policies and lower interest rates to ease the credit crunch.

Secondly, the sequence of the reform measures was also disputable. Cho (2001) alleged that asymmetric financial restructuring measures, while reforming commercial and merchant banks, but leaving other non-bank financial institutions such as investment trust companies exposed to trouble, had created the moral hazard problem.25

Bubbles created

Also, the IT and venture sectors were overly bolstered by the government, which afterward resulted in the burst of the IT bubble. In fact, this phenomenon was not limited to Korea. Along with the collapse of the U.S. NASDAQ, most of the technology-related stock bubbles worldwide went burst in 2000. However, what was peculiar about Korea was that the creation and nourishing of small and medium-sized venture firms was government-led. The start-up companies needed government approval in almost every step of their development. It was the government, which granted certain firms venture status, and the government provided the lion's share of investment capital to these small start-up firms. Also, to be listed in the KOSDAQ, the Korea's equivalent of NASDAQ, venture companies had to receive approval from the government. Due to this severe government interference, the government was largely responsible for creating a bubble in the KOSDAQ market Furthermore, several financial scandals related to the procurement of favorable government funds broke out later on.

Aftermath of the Reform: New Environments and Future Challenges

The Korean economy has to live with new conditions and environments that were created as a result of various reform measures introduced during the last several years. These changes will be a double-edged sword to the Korean economy. In

many aspects, the changes that were brought about by the crisis will be challenges to the Korean government and firms. Also, these changes can be golden opportunities to many economic actors once they are properly made use of. End of the high growth era

In terms of macroeconomic indices, a lower investment rate and a lower potential growth rate will prevail from now on.26 According to Barro (2001), countries that experienced a currency crisis ended up with reduced investment ratios for a certain period of time. However, he failed to detect a persisting adverse influence of crises on growth and investment.27 Chopra et al. (2001) also estimated that the Korean economy's potential growth rate from 2000 to 2005 would be as low as 6 percent To an economy like Korea, which has long been accustomed to high investment and high growth rates, this change will be difficult to cope with at least for a while.

The lower investment rate was accompanied by a lower saving rate. The saving rate, which peaked to 40 percent in the mid-1980s, gradually declined in the 1990s. In particular, in the process of overcoming the crisis, the propensity to consume increased as financial institutions provided cheaper loans to individual households. This, in turn, lowered the saving rate, which was barely 30 percent as of 2001. With this lowered saving rate, the Korean economy will not be able to return to the era of high-investment and high-growth.

Deteriorated income distribution

Another side effect is the aggravated income distribution, measured by the Gini index.28 According to the National Statistical Office, the Gini index, whose average value for 1990-97 was 0.286, deteriorated after the crisis to 0.317 and 0.319 in 2000 and 2001 respectively. In order to relieve this problem, the Korean government will have to continue to build a better social welfare system.

However, the deteriorated income distribution indices do not necessarily mean the collapse of the Korean middle class. It was mostly due to the widening gap between the richest and the poorest. As shown in the following table, the income gap between the poorest 20 percent and the richest 20 percent widened significantly after the crisis. Even with this deterioration, one study by KDI shows that the share of the middle class in Korea remained unaffected by the crisis.29

Table 12. Income Distribution Indices of Korea

1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 Gini 0.28 0.31 0.320 0.317 0.319 Income gap* 4.49 5.41 5.49 5.32 5.36 Note: * Income gap between the richest 20 percent and the poorest 20 percent. Source: Maeil Business Newspaper (in Korean, February 21,2002).

44 Doowon Lee

Liberalized capital market

Another notable change was the fully liberalized commodity and financial markets and the presence of foreign shareholders in the Korean economy.30 As a result of this liberalization process, the Korean economy is currently more exposed and vulnerable to external shocks than before. The ratio of exports to GDP increased substantially, and as more foreigners took over shares of Korean financial institutions and leading companies, it became more and more difficult for the government to carry out its conventional industrial policies. The presence of the foreign shareholders and foreign investors in Korean firms and financial institutions, however, brought about many positive changes as well. Relatively speaking, the governance structure of Korean firms, whose shares are largely owned by foreigners, has become more transparent. Also, the government no longer controls those banks with foreign investment.

Changed structure of financial market's loans and deposits

The loan and deposit structure of financial market changed as welL First, as more people sought safe havens to deposit their money, the banking sector attracted a larger share of deposits compared to the non-banking sector. As a result of this, the role of non-bank financial institutions (NBFI) such as investment trust companies and merchant banks has shrunk. In particular, the corporate bond market, which was handled mostly by these NBFIs before the crisis, was severely depressed in 1999 and 2000.

Another notable change in the structure of the financial market is the increased loans to individual households. Many banks, particularly banks with more foreign shareholders, directed more of their loans to households than to firms. As a result of this, the ratio of loans made to firms out of the total loans decreased from 70.8 percent in 1997 to 57 percent in 2001.31 The increased loans to consumers coupled with a low interest rate have helped the consumption level to rebound since 1999. However, the Korean households became burdened with unprecedented liabilities. Households' liabilities jumped from W 182 trillion as of January 1997 to W 335 trillion as of December 2001, and the Korean households became highly leveraged compared to those in the U.S. and Japan as shown in the following table. The higher burden of household debt can be potentially dangerous to the Korean economy as it can dampen the future consumption level and can be degraded into dud loans once the business cycle turns downward.

Table 13. International Comparisons of HH Liabilities (2000) Korea* ' U.S. Japan Liability/disposable income (%) 90 114 121.2 Financial asset/liability 2.52 4.2 3.7 Note: *1Tie Korean data are for 2001.

Sources: SERI (in Korean, February 27,2002).

Bigger burden on the budget

Traditionally, the fiscal stance of the Korean government was very healthy. Before the crisis, it enjoyed either a balanced or a slightly surplus budget balances for a long time. However, during and after the crisis, the role of the budget was rapidly expanded in order to establish a social safety net, provide fiscal stimulus and to set up public funds. In particular, due to the astronomical amount of public funds, which exceeded W 150 trillion as of the end of 2001, the burden of interest and principal payments for the government-guaranteed bonds will be extremely heavy for the next regime. For example, starting from 2003, the annual repayment for the public funds will be W 9.6, 27.4, 21.1 and 13.8 trillion for the year 2003, 2004, 2005 and 2006. The best way to finance this is to utilize the recycled money from the public funds. However, as shown in Table 4, not much has been recycled from the public funds so far. Basically, most of the public funds spent to reimburse depositors will not be retrieved. However, almost all of the public funds spent on the purchase of NPLs and recapitalization of troubled financial institutions will be able to be retrieved once the real estate and stock market prices recover its pre- crisis levels.

Another burden comes from the deficits of various public funds, which were generously expanded after the crisis. For example, the National Pension Funds (NPF) expanded its services by several folds. In the end of 1997, only 7.8 million people were enrolled in the NPF with 0.15 million people benefiting from it. However as of 2002, approximately 16.4 million people are covered by the NPF and 1.1 million people are receiving benefits.32 Along with the rapidly aging Korean population structure, Yoon's study (in Korean, 2001) predicted that the NPF would be depleted as early as 2040 unless the generous payment of the current system is modified. Not only is the pension fund endangered but the healthcare system is also already suffering from deficit after the recent health care reform that separated the prescription and sales of drags.

5. CONCLUDING REMARKS

The Korean economy has gone through a bumpy road of crisis, recovery and a mild recession from 1997 to 2001 after the outbreak of the financial crisis. This paper summarizes the process of recovery and the internal and external factors behind it. Also, several valuable lessons learned from the experience of recovery and future implications are discussed.

Four major reform efforts driven by the Korean government with the help of the IMF in 1998 and 1999 played the major role in overcoming the crisis. However, there were some internal and external factors that also helped the recovery in 1999 and 2000. They were the strong export and investment

46 Doowon Lee

performance of the IT industries, revived household consumption and expansionary fiscal and monetary policies of the government Due to these reform efforts and policy changes, the Korean financial and corporate sectors regained their financial soundness. Also, the labor market became more flexible, and the public sector was deregulated and privatized. However, as the business cycle turned downward since late 2000, people began to realize that the economic reform was incomplete.

Out of the past experiences of crisis and recovery, several lessons are learned. First, people realized how important it was not to be misled by the macroeconomic fundamentals. Even though the macroeconomic fundamentals were healthy and strong, the erosion of microeconomic foundations could bring about a financial crisis. However, it was the strong macroeconomic fundamentals such as the sound government fiscal stance and high household saving rate that enabled the rapid recovery. In this sense, the strong macroeconomic fundamentals can be interpreted as a double-edged sword. Second, it is important to pursue a reform in a consistent and persistent manner. Due to the changes that have occurred in the process of reform, the Korean economy is now facing several new challenges. It now has to become more accustomed to slower investment and growth. There has been deterioration in income distribution with a wider gap between the rich and the poor. Also, with the full liberalization of the Korean economy, the conventional government-led development strategy will not work any more. The loan and deposit structure of financial institutions changed as well with potential side effects. Lastly, due to the hastily established public funds and generously expanded social welfare system, the role and burden of government budget has been greatly enlarged.

Notes

1 Okun's law states the relationship between unemployment level and economic growth. When an economy grows, unemployment level falls. Okun's law calculates how much the unemployment level falls when an economy grows. While the additional 1 percent growth rate had lowered the unemployment rate by 10 percent before the crisis, the additional 1 percent growth rate has lowered the unemployment rate by 16 % after the crisis.

2 Another study also shows more flexible labor market conditions in Korea. The job- finding rate and job-losing rate of 1997 were 1.79 and 2.09 respectively. After the crisis, they were 3.0 and 2.75 respectively in 2000. It shows that it has become easier to hire and fire labor after the crisis. Refer to Samsung Economic Research Institute, "The Changes of the Korean Economy During the 3 Years under IMF Crisis" (2001).

3 At the end of 1998, 34.9 percent of loans went to households. However, this figure

jumped to 51.8 percent by September 2001. Refer to SERI (in Korean, February 27, 2002).

4 Refer to The Economist (July 29, 2000: 69).

5 ICR is the ratio of operating profit over interest expenses. In 2000 and 2001, 37 percent and 16 percent of listed firms had ICR less than one, respectively. Refer to Chosun Ilbo (in Korean, March 29, 2002).

6 Refer to SERI (in Korean, 2000: 78).

7 For example, the ratio of interest expenses to the total sales of manufacturing firms in Japan (1996) and Taiwan (1995) were 1.0 percent and 2.2 percent respectively. Refer to Bank of Korea, Monthly Bulletin (in Korean).

8 According to the OECD, Korea was ranked as the second strictest nation in terms of protection for regular workers. Refer to OECD (1999), Employment Outlook.

9 For example, in the U.K., measures have been introduced to make the female employment easier, to reduce the regulation on working hour and to ease the layoffs. Also, in the Netherlands, the tripartite agreement between the management, labor and the government was made in 1982, which increased the wages, shortened working hours, introduced the early retirement system and created part time labor. Refer to Kim, et. al. (in Korean, 2000: 87). lso, refer to Yoo (in Korean, 1999) for the experiences of OECD countries to make the labor market more flexible.

10 For further detailed analysis, refer to Figure 7 of Jones (2002).

11 As of the end of 2001, Korea's foreign exchange reserve is the 5th largest in the world. Also, Korea has attracted more than US$10 billion FDI annually during 1999 and 2001.

12 Moody's rating for Korea used to be 'Al' before the crisis. It was degraded to 'Bal' in December 1997. Later, it was upgraded to 'Baa2' in December 1999, and 'A3' in March 2002. Also, S&P has upgraded from 'B+' of December 1997 to 'BBB+' in November 2001. Refer to Maeil Business Newspaper (in Korean, March 4, 2002).

13 However, there is a great deal of possibility that the actual status of the Korean banking industry is in better shape than that of Japan as many of the Japanese de facto NPLs are categorized as normal loans. For example, according to the recent estimate made by Ernest & Young Co., the ratio of NPL to GDP in Japan was estimated to be 26 percent in 2001, while the same figure for Korea was merely 14 percent Refer to Maeil Business Newspaper (in Korean, November 2, 2001).

14 Refer to Bank of Korea, Monthly Bulletin (in Korean, April 2001). Also, according to Bank of Korea (in Korean, January 2, 2001), the total number of employees in the IT sector as of June 2000 was approximately 530 thousand, composing 2.5 percent of the total labor force. However, it composes 16 percent of GDP.

15 The number of venture firms registered in the Bureau of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises was 2,042 (1998), 4,934 (1999), 8,798 (2000), and 11,392 (2001). Refer to Munhwa Ilbo (in Korean, January 17, 2002). According to the Bureau of SME, the number of venture firms increased to 11, 286 by January 2002.

16 According to the recent study of Bank of Korea, it is estimated that 1 percent decrease of interest rate boost the annual consumption level by 0.4 percent Refer to Bank of Korea (in Korean, January 25, 2002).