第二言語習得における普遍文法の役割に関する研究は、1995年にチョムスキーよってミニ マリスト・プログラムが提唱されて以来、もっぱら機能範疇に属する素性の習得可能性に焦 点を当てるようになった。その一例として、若林(1997, 2002a)の、日本人とスペイン人に よる、英語の時制節の主語に関わる素性の習得に関する研究があげられる。その中で、若林 は、扱ったデータが完全言語転移説では説明がつかないとし、それに代わる説として語彙転 移・語彙習得(Lexical Transfer / Lexical Learning)説を提案した。このモデルによれば、 第二言語で必要な素性は、母語の心的辞書から第二言語のそれへの転移と、白紙状態から学 習する二つのプロセスをとおして行われ、後者のプロセスにおいては、可視統語(overt syntax)レベルで併合される素性から習得が始められるということである。さらに、若林は、 日本人が英語の主語を習得する場合では、母語からの転移は起こらず、比較的早期に学習可 能であると主張した。

本研究では、英語習熟度の異なる日本人100人から収集した、英語の時制・非時制節に存在 する主語と動詞屈折の習得データを分析した。この結果からは、若林が主張する習得順序パ ターンは認められなかった上、母語に存在するトピック構造の転移が観察された。これを基 に、本研究は、Tsimpli らの提唱する完全言語転移・ UG アクセス制限 (Full Transfer / Limited Access) 説を支持する。さらに、言語転移のメカニズムについて考察する。

キーワード

ミ ニ マ リ ス ト プ ロ グ ラ ム(Minimalist Program)、 第 二 言 語 習 得 理 論(Second Language Acquisition Theory)、言語転移(Transfer)、日本人英語学習者(Japanese Learners of English)、 主語(Subject)

1.Introduction

Within the generative framework, various accounts have been proposed in order to give an explanationforgrammaticalphenomenainSLA.Amongstthemarethe‘MinimalTrees’hypothesisby

SubjectsandVerbalInflectionsinSLA:

InDefenceof“FullTransfer/LimitedAccess”Model

1)第二言語習得における主語と動詞屈折の分析: 完全言語転移・UG アクセス制限説の擁護

ChiekoKuribara

栗 原 千 恵 子

Vainikka&Young-Scholten(1994,1996a,1996b),the‘WeakTransfer’theorybyEubank(1993/94, 1994a,1996),the‘FullTransfer→FullAccess’modelbySchwartz&Sprouse(1994,1996),and the‘FullTransfer/LimitedAccess’accountbyTsimpli&Roussou(1991)andTsimpli&Smith

(1991).Thevalidityofthesemodelshasbeenexaminedandquestionedovertheyears.Arecent criticismcomesfromWakabayashi(2002a),whichstudiestheacquisitionofnon-nullsubjectsin EnglishbyJapaneseandSpanishspeakers,cruciallyrelyingontheMinimalistframeworkproposedby Chomsky(1995).Hearguesthatthedataanalysedinhisstudycannotbeaccountedforbyanyofthe abovetheories,includingthe‘FullTransfer/LimitedAccess’model,whichassumesthattheinitial stateofL2grammarconsistsofL1syntacticproperties,andthatparameter-resettingisvirtually impossible.ThemodelregardsSLAasaprocesswherelearners“misanalyse”asurfacestructureofa targetlanguage,byassociatingL1featureswithL2morphophonologicalforms,whichimpliesthatthe syntacticrepresentationbuiltthroughthisprocessisthesameasthatoftheirL1.Wakabayashiagrees withtheviewthattransfertakesplaceinSLAbutdisagreeswiththeclaimthatnoparameter-resetting takesplace.Heproposesatheorycalledthe‘LexicalTransfer/LexicalLearning’modelandargues thatthisisabletoprovideaplausibleaccountforhisinterlanguagedata.Accordingtothemodel,SLAis carriedoutmainlybytwoprocesses:lexicalfeaturelearningtriggeredbyPF/overtcues,andfeature transferfromonelexicontoanother.

Thepresentpaper,investigatingtheacquisitionoffeaturesinvolvingsubjectsinEnglishby Japanesespeakers,attemptstoshowthattheresearchfindingscanbeplausiblyexplainedintermsofL1 transferratherthanacquisitionofnewfeatures.Thestudyalsocontributestobetterunderstandingofthe term,transfer.

Theorganisationofthepaperisasfollows:Insection2,therelevanttheoreticalbackgroundsare described.ItbeginswithanoutlineofthesyntacticframeworkproposedbyChomsky(1995).Thisis followedbyadescriptionofthetheorydevelopedbyWakabayashi(1997,2002a),whichaccountsfor theparametricdifferencesbetweenEnglishandJapanese,focusingonthederivationofsubjectsinthe respectivelanguages.Then,twoacquisitionmodelsareintroduced:Wakabayashi’sSLAtheorycalled the‘LexicalTransfer/LexicalLearning’model,andHoekstraetal.’sL1acquisitiontheory,which offersanaccountfortheacquisitionpatternofrelevantstructures,observedinthedataofL1acquirersof English.TherationalebehindtakingL1acquisitionintoconsideration,aswellastestingthevalidityof Wakabayashi’sSLAmodel,istoseewhetherourresearchdatawouldshowaconsistentpatternwith thatofL1acquisition,whichisassumedtobecarriedoutbyacquiringasetoffeaturesrequiredbythe targetlanguage.ItispossiblethatL2acquisitionstilltakesplaceviafeaturelearning,conformingnotto themodelsuggestedbyWakabayashibuttothepatternobservedinL1acquisition.Afterthetheoretical assumptionsareintroduced,ourempiricalstudyispresentedinsection3.Thisincludesthesyntactic

theoryweadopted,specificresearchquestions,methodology,andresultsoftheexperiment.Theresults arediscussedinsection4,andaconclusionisdrawninsection5.Thepaperisroundedoffwithsome implicationsforatheoryoftransfer,withparticularreferencetoSelinker(1992,1996).

2.TheoreticalBackground

2.1.TheMinimalistProgram(Chomsky1995)

Wakabayashi(2002a)adoptstheMinimalistProgram(MP)ashistheoreticalframework.It regardslinguisticknowledgeasacomputationalsystem,andthesystemisstrictlyderivational.The derivationstartsfromtheLexiconandendsatLF,andsomewhereintheprocessasyntacticobjectissent toPF(spell-out).Inthelexicon,allthelexicalitems2)neededtoformasyntacticobjectbecome associated with formal/grammatical features. Those features can be categorised into either [+interpretable]or[−interpretable].Then,thosebundlesoffeaturesareputintoanarray(Numeration). Thecomputationalsystemtakesthisarrayoflexicalitemsfromthelexicon.Theselexicalitemsor syntacticcategoriesmergetogetherinapair-wisefashiontoformalargerconstituent(Merger).Atthe sametime,thegrammaticalfeaturesgiverisetoachainofmappingoperations(Checking),whose purposeistoeliminateallbuttheinterpretablefeaturesinthePF-andLF-levelsrespectively.Feature checkingmaybecarriedoutbyovert/covertmovement(Move/Attract).Allthestrongfeaturesand phonologicalfeatures,whichtriggerMove,areeliminatedbeforethepointofSpell-Out,andthe syntacticobjectissenttothePFlevel.Ontheotherhand,therestofthe[−interpretable]features,i.e. featureswithoutsemanticcontents,areeliminated,andtheconfigurationwhichonlycontainsthe [+interpretable]featuresconvergesattheLFlevel.TheseoperationsaresubjecttothePrincipleof Procrastinate,whichrequiresthemtotakeplaceafterSpell-Outunlessthereissuchafeaturethaturges overtmovement.Theseareschematicallypresentedinfigure1:

Note : A-P knowledge = articulatory-perceptual C-I knowledge = conceptual-intentional

C-I Knowledge Derivation

A-P Knowledge

Lexicon

Spell-Out

PF Interface Level

LF Interface Level

Figure 1. Mechanism of Syntactic Derivation

2.2.ATheoryofParametricDifferencesbetweenEnglishandJapaneseSubjects

(Wakabayashi1997,2002a)

Based on the above framework, Wakabayashi proposes an account for parametric differences between English, Spanish and Japanese subjects; only the theories on English and Japanese are presented here. Assuming that derivation takes place in a bottom-up manner, VP is formed at some point, and then in English, T merges with VP. English T possesses the strong D feature and Nominative case, both of which are considered to be [−interpretable]. The [strong D] of T, which needs to be checked and deleted in overt syntax, attracts the categorial feature of DP in the [Spec VP]. This induces the movement of the whole constituent of [D, first-person, singular, Nominative] to the [Spec, TP]. Checking operations take place between T and its specifier DP, which result in the erasure of the [Strong D] feature of T, and the [Nominative] features of T and DP. In covert syntax, the tense and Φ -features of the verb are attracted to T. The Ф-features of V, being [−interpretable], are checked by those of the DP in [Spec, TP] and erased. The series of these processes are schematically presented below:

(1)a.Ikicktheball..

b.OperationsinOvertSyntax

c.OperationsinCovertSyntax

InJapanese,ontheotherhand,anoversubjectnounphrase,ifitisselectedfromthelexicon, mergesastheSpecofVPinovertsyntax,andthenTmergeswithVPincovertsyntax.Theseprocesses areschematicallypresentedbelow:

TP

T, [1-person, singular]I i

VP T

V, kickj the ball [−past]T ti

[1-person, singular, −past]j

TP

T, [D, Nominative, 1-person, singular]I i

VP [Strong D, Nominative, −past]T

V, kick the ball ti

(2)a.(watashi-ga)sonobooru-okeru.

(I)that ball-acckick-pres

b.OperationsinOvertSyntax

VP V, watashi-ga

sono booru-o keru

c.OperationsinCovertSyntax

TP

VP T

V, [−past]T

keruj sono booru-o

subject [−past]j

DP

Thus,thedifferencebetweenEnglishandJapanesesubjectsisexplainedintermsofwhetherT mergesinovertsyntaxandwhetherithasastrongDfeature:EnglishTmergesinovertsyntaxandhasa strongDfeature,whereasJapaneseTneithermergesinovertsyntaxnorhasastrongDfeature.

2.3.The‘FeatureTransfer/FeatureLearning’Model(Wakabayashi1997,2000a)

Assumingthatcross-linguisticdifferencesareattributedtothedifferencesinfeaturespecifications, WakabayashiputsforwardanSLAmodelwhereL2learnersusethesamecomputationalsystem availablefortheirnativelanguage,buthavetobuildalexiconbasedontheinput.Thelatteriscarriedout eitherbytransferringfeaturesfromtheirL1lexiconorbylearningnewfeaturesfromscratch.This processoffeaturelearningisinitiatedbyaPF-effect,bywhichWakabayashimeansthefeaturesthat requirethelexicalitemtomergeinovertsyntaxareacquiredearlierthanthosethatrequirethelexical itemtomergeincovertsyntax.Learnersalsohavetolearnwhichitemstoincludeinthenumerationand whichfeaturestoassociatewithwhichlexicalitems.Thispredictsthat‘onlywhenthelexicalitemis includedinthenumerationdoesL1transferemerge(p.99)’.Thisaccountsforthefactthatlearnersdo notexhibitthepropertiesoftheirL1duringtheveryearlystageofSLA.Referringtotheresultsofhis study,heconcludesthatinthecaseoftheacquisitionofovertsubjectsinEnglishbyJapanesespeakers, learningofthestrongDfeatureofTtakesplacewithoutL1transfer.

2.4.L1AcquisitionStudiesonNullSubjectsandFiniteness

Nullsubjectsarealsoawell-discussedissueinfirstlanguageacquisition.Ithasbeenreportedthat thereisastageduringwhichchildrenomitdeterminersandsubjectpronouns.Thisalsocoincideswith theomissionofinflectionalmorphology.Anexplanationforthiscorrelationbetweennullsubjectsand rootinfinitivesisoffered,forexample,byHoekstraetal.(1995,1999).Theysuggestthattheproperty which those two phenomena have in common is the semantic notion of‘specificity’:verbal morphologyexpressestemporalspecificity,whilstdefinitedeterminersandpronounsmarkspecificDPs. However, there is a great deal of evidence that children have the knowledge of Spec-head agreement:Hoekstraetal.show,citingseveralstudies,thatchildrenuseagreeingformsofverbswitha highdegreeofaccuracy,andthatchildrenproducetheagreeingformofthesameverbimmediatelyafter producingarootinfinitive.TheyfurtherpresenttheresultsofGerken&McIntosh(1993),which indicatesthatchildrenseemtoknowboththepresenceofafunctionalpositionprecedingnounsand whatthecontentofthepositionshouldbe.

Takingthetwoobservationstogether,Hoekstraetal.claimthatwhatislackinginchildren’s sentences is‘finiteness’,thegrammaticalencodingofspecificity.Accordingtothem,thereisa temporal / deictic operator in the C domain that binds verb.They consider the morphosyntactic realizationofthechainlinkingthosetwoelementsasfiniteness.ThesameappliestoDandnoun.The morphosyntacticrealizationvariesfromalanguagetoalanguage;inthecaseofEnglish,itisNumber thatisrealised.Hoekstraetal.claimthatitistheunderspecificationofNumberthatmakesthechain invisible;hencethelackoffiniteness.Thisisreflectedinearlygrammarasacorrelationbetweennull subjects(ordeterminerlessnouns)androotinfinitives.

3.Study

3.1.SyntacticAssumptionsonEnglishandJapaneseSubjectsandaRelatedIssue

FollowingWakabayashi(2002a)andFukui(1986/1995a,1995b),weassumethatEnglish possessesthestrongDfeatureandNominativeCaseinT,andΦ-featuresinV,whereasJapanese possessesnoneofthem.Therefore,inEnglish,anovertsubjectisraisedfrom[Spec,VP]to[Spec,IP]in ordertocheckoffthestrongDfeatureandNominativecaseinT.WhereasinJapanese,anovertsubject isplacedin[Spec,VP]andisgiventheNominativecasemarker-ga,asaresultofmergerwithaV’.In thecaseofJapanese,however,afiniteclausedoesnotneedtohaveanovertsubject;theclauseis allowedtohaveanullsubject.

AclausewithoutanovertsubjectcanalsobefoundinEnglish.Itisanon-finiteclausewithanull subject,PRO:

(3)a.[IPIkicktheball].

b.[IPPROTokicktheball]isdangerous.

Weassume,followingChomsky&Lasnik(1995),thatPROisD,andcarriesNullcaseandasetofΦ- features.Justlikeitsovertcounterpart,PROisraisedfrom[Spec,VP]to[Spec,TP]inordertocheckoff thestrongDfeatureofto-infinitive.ThenullcaseofPROandthatofthenon-finiteTarealsochecked offatthispoint.

(4)OperationsinOvertSyntax

TP

T, is dangerous TP

T, [D, Null Case, Φ-features]PRO i

VP [Strong D, Null Case, −finite]T

V, kick the ball ti

Thus,thesyntacticdifferencesbetweenovertandnullsubjectsinEnglisharethetypeofstructural caseandthecontentofΦ-features.FollowingChomsky(2000),weregardstructuralcaseasasingle unidentifiablefeature,treatingNominativeandNullcasesasvariantsofthesameentity.Wealso understandthatΦ-featuresareundifferentiatedwithrespecttothevalueoftheindividualfeaturesofthe Φ-set(e.g.[+/ −plural]),andcanonlybedeletedasaunit.Manifestationofstructuralcaseis determinedbythetypeofT,eitherfiniteornon-finite3);whilstmanifestationofΦ-featuresonVerb dependsonthoseofthesubject.

IndiscussingthesyntaxofsubjectsinJapanese,weneedtotakeacloserlookatthephrases occurringattheleftperipheryofasentence.Itiswell-knownthatinJapanese,morethanonenoun phrasecanbebase-generatedbeforeapredicate(Hoji1985;Saito1985;Tateishi1991/1994),either beingmarkedwiththeNominativemarker-gaorthetopicmarker-wa.Tateishi(1994)showsthat strictlyspeaking,therearemaximallytwonounphrasesthatcanbemarkedwith-ga,thetwocloserto thepredicate.They,however,differinthatonlytheoneclosesttothepredicateisθ-marked;theotheris non-θ-marked.Tateishirespectivelycallsthemθ-markedsubjectandMajorSubject.Accordingtohim,a sentencecanhaveanothernon-θ-markednounphrase,precedingMajorSubject.ItiscalledPureTopic. Amongstothersyntacticproperties,acharacteristicofPureTopicisthatitcanonlybemarkedwith-wa,

whichcontrastswiththeothertwonounphrases,θ-markedsubjectandMajorSubject,inthattheycan bemarkedeither-gaor-wa.

(5)a.θ-markedsubject

Taroo-ga/-wahon-oyomu. Taro-nom/topbook-accread-pres

‘Taroreadsabook.’

b.MajorSubject̶θ-markedsubject Niigata-ga/-wa sake-gaumai. Nigata-nom/topsake-nomgood

‘ItisNigatawheresakeisgood.’

c.PureTopic̶MajorSubject̶θ-markedsubject

keizai-nyuusu-wa/*-ga Nikkei-gaYukijirushi-mondai-gadaiichimen-ninot-teiru. Economy-news-top/*nomNikkei-nomYukijirushi-problem-nomfrontpage-datappear-prog

‘Astobusinessnews,itisNikkeiwheretheprobleminvolvingYukijirushiappearsonthefront page.’

Otherphrases,apartfromnounphrase,canbemarkedwith-wa.When-waisattachedtoaphrase otherthannounphrase,italwaysrequiresthesentencetohavea‘contrastive’reading.Thistypeof sentencealwaysinvolvesmovement(Hoji1985;Ishii1991;Saito1985).

(6)PPtopicwithacontrastivereading London-ni-waiTaroo-gatiit-ta. London-to-topTaro-nomgo-past

‘ToLondon,Tarowent.(buttootherplacesomebodyelsewent).’

Tocomplicatematters,notallsubjectsortopicsneedtoappearinaJapanesesentence.

(7)a.AnexamplewhereonlyaPureTopicappears kore-wabunryoo-womachigae-ta-kana. This-topquantity-accmistake-past-seem

‘Basedonthis,itseemsthat(we/I)putawrongquantity.’

b.AnexamplewhereonlyaPPtopicappears

London-de-wagogo-no koocha-otanoshimi-mashi-ta. London-in-topafternoon-gentea-accenjoy-polite-past InLondon,(we/I)enjoyedafternoontea.’

UnlikeJapanese,Englishdoesnotgrammaticallydistinguishtopicfromsubject,butpossesses similarsurfacestructures;aphraseinthesubjectpositionisnormallythetopicofasentence(Shibatani 1991).However,whenanotherphrasebecomesthetopic,itismovedandplacedatthesentence-initial position.

(8) a.Subjectasatopic

Webakedcakelastnight.IttastedbetterthanourMom’s.

b.Otherphraseasatopic

In Londoni,weenjoyedafternoonteati.

SomesurfaceresemblancesareobservedbetweenEnglishandJapanese.Thesurfacestructuresof

(8a)and(8b)aresimilartothoseof(5a)and(6)respectively.In(8a)and(5a),thereisonesubject whichisθ-marked;In(8b)and(6),thesentencestartswithatopicalisedPP,whichisfollowedbyaθ- markedsubject.However,therearesomedifferences,too.AfiniteEnglishsentencemusthavea(n overt)subjectDP.Incontrast,aJapanesesentencedoesnotneedtohavea(novert)subject;itmayonly haveaPureTopicoratopicalisedphrasebeforeapredicate,aswesawin(7).

3.2.ResearchIssues

TheaimofthisresearchistofindoutwhetheradultL2learnersprocessastructureofatarget languageasaresultoflearningrelevantfeatures,focusingontheacquisitionofsubjectsbyJapanese learnersofEnglish.WehaveidentifiedthatdifferencesbetweenEnglishandJapanesesubjectsresidein thepresenceorabsenceofstrongDfeatureandNominativecaseinT,andΦ-featuresinV.Thenwe havereviewedtwoacquisitionmodels.AccordingtoWakabayashi,nullsubjectsininterlanguageoccur during the period where L2learnershavenotyetlearntappropriatefeaturesortakentheminto Numeration,andSLAstartswithtransferringandlearningfeaturesthatrequiretherelevantlexicalitem tomergeinovertsyntax.HeclaimsthatinthecaseofJapanesespeakerslearningnon-nullsubjectsin English,transferisnotinvolved.AccordingtoHoekstraetal.,thephenomenaofnullsubjectsandroot infinitives are due to the problem with grammatical encoding of‘specificity’causedbythe underspecificationofNumber.Thereasonbehindthisisthatthereisastrongevidencethatchildrenhave

theknowledgeofSpec-headagreement.ThisisalsoreportedinthesurveyonrootinfinitivesbyPrévost

&White(2000).Childrenuserootinfinitivesinsteadofincorrectinflectionalforms,untiltheyidentify correctforms.Thisspeculationisbasedonthefactthatchildrenusecorrectagreementmorphologyif theyproducethematall.Takingtheseintoconsideration,wehavepreparedthefollowingconstructions:

(9)a.*Null Expletives (*NullExp)

IntheRockyMountains∅issnowingatthemoment.

b.*DP Infinitive(*DPInf)

John tostudylawatOxfordUniversitypleasedhismother.

c.*Agreement Errors(*AgrError)

Inspiteofmucheffort,they stillhasn’tfinishedtheirwork.

Theconstructionsin(9)areungrammaticaleitherbecauseafeatureislackingorbecausetypesofa featuredonotmatch.In(9a),thefiniteInflhasNominativecaseandthestrongDfeature,whichareto becheckedanderasedinovertsyntaxagainstthefeaturesofthesubject.However,thesubjectiseither nullorabsent.Intheformercase,Nominativecasecannotbecheckedoff.Inthelattercase,neither NominativecasenorthestrongDfeaturecanbecheckedoff.Hencethestructureresultsinbeing ungrammaticalinbothcases.In(9b),NullcaseandthestrongDfeatureinto-infinitiveneedtobe checkedanderasedinovertsyntax4).WhilstthestrongDfeaturecanbecheckedoffagainstthatofthe overtsubject,Nullcasecannotbe.Thismakestheconstructionungrammatical.In(9c),thespecification ofNumberassociatedwithVdoesnotmatchwiththatofthesubjectDP.TheΦ-featurecannotbe checkedanderasedincovertsyntax;hencetheungrammaticalityoftheconstruction.Inshort,the detectionofungrammaticalityinboth(9a)and(9b)requirestheacquisitionofthesamefeature(s),i.e. structuralcase(aswellasthestrongDfeature);whereas,therecognitionofungrammaticalityin(9c) involvestheacquisitionoftheNumberfeature.

RecallthatWakabayashiclaimsthatthefeatureswhichmergeinovertsyntaxwouldbeacquired earlierthanthosewhichmergeincovertsyntax.Wecouldthenexpectthatlearnerswouldnoticethe ungrammaticalityof*NullExpand*DPInfaroundthesametime,andthattheungrammaticalityof

*NullExpand*DPInfwouldbenoticedearlierthanthatof*AgrError.Thisisbecausethesame featureswhichneedtobecheckedinovertsyntaxareresponsiblefor*NullExpand*DPInf5),and becausetheNumberfeature,whichmergesincovertsyntax,isliablefor*AgrError.

If,ontheotherhand,SLAiscarriedoutinthesamewayasL1acquisition,wewouldexpectthat learnersnoticethemismatchinthetypeofstructuralcasein*NullExpand*DPInfaroundthesame timeasorsoonaftertheynoticetheagreementmismatchin*AgrError.ThisisbasedonwhatHoekstra

etal.argue.InEnglish,specificationofNumberisresponsibleforthevisibilityofsubjectDPs.Inother words,wewouldbeabletoseeacorrelationbetweencorrectuseofverbalinflectionsandthatofsubject DPs.Thuslearners’performanceisexpectedtoshowaparticularpatternofa‘clusteringeffect’6).

3.3.DataCollection

Aspartofalargerstudy,agrammaticalityjudgementtestwasadministeredto100nativespeakers ofEnglishand100JapaneselearnersofEnglish.Theywereaskedtorespondto100sentencesby circlingOK,NotOKor?.ThosesentencesincludedthethreeungrammaticalEnglishconstructions mentionedintheprevioussection,andeachconstructionconsistedoffivesentences.(seeAppendixA).

3.4.MethodofAnalysis

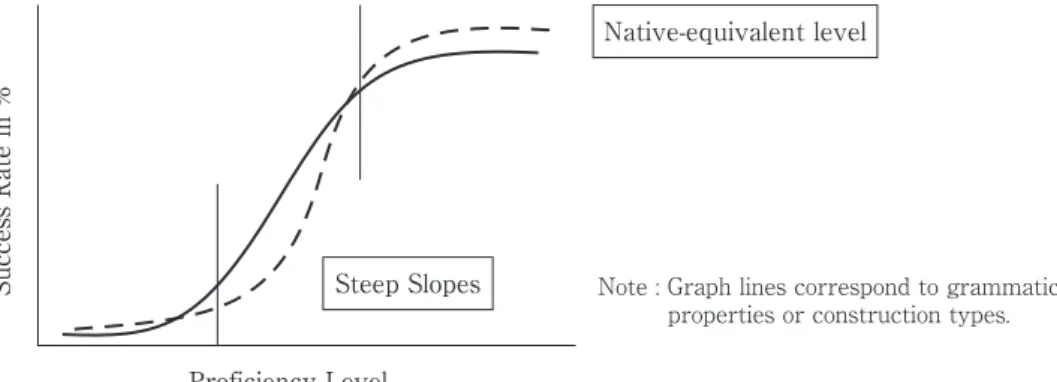

ClusteringisafundamentalconceptintheUGparametertheory,whichisunderstoodasa phenomenonwhereunderlyinglyrelatedgrammaticalpropertiesemergetogetherinalanguage(Meisel 1995).WithintheMPframework,parametricdifferenceisunderstoodasthepresenceorabsenceofa particularfeature,orthedifferenceinitsbinaryspecification.Wethereforeassumethatifaparticular featurebecomesavailableforadultlearners,aclusteringeffectwouldbepresent,beingmanifestedin our data as the following pattern: at first, learners’successratesstayatalowlevelorincrease moderatelywithproficiencyuntilathresholdlevel.Atthispoint,successratesincreasemuchmore rapidly(adiscontinuityeffect)7)andultimatelyapproachthoseofnative-equivalentlevels(anultimate successeffect).8)Thiswillhappenforallconstructiontypesassociatedwiththefeaturearoundthesame proficiencylevel(aclusteringeffect).IillustratethisbehaviourinFigure2,renamingitasafeature- acquisitioneffect.

Inordertoexaminewhetherthedataexhibitsuchapattern,wefirstdividedtheJapanesesubjects into10proficiencygroupswitha30-pointinterval:

Proficiency Level

Success Rate in %

Native-equivalent level

Note : Graph lines correspond to grammatical properties or construction types. Steep Slopes

Figure 2. Feature-acquisition effect in the relationship between success rate and proficiency level

Score 360- 390- 420- 450- 480- 510- 540- 570- 600- 630-

Number 9 16 10 7 6 10 13 9 8 12

Table 1. Proficiency bands based on the TOEFL test scores and the number of Japanese subjects in each band

ForeachproficiencygroupoftheJapanesesubjectsandforthenativespeakergroup,thenumberof responsesclassifiedintocorrect,incorrectandundecidedwerethentotalledandcalculatedas percentageswithrespecttoeachsentenceandconstructiontype.

Thepresenceofafeature-acquisitioneffectwasalsoinvestigatedusingstatisticalprocedures.The existenceofadiscontinuityeffectinthedatawastestedbyapplyinglogisticregressionanalysis.Inthis analysis,thefrequencydatawerefirsttransformedintologisticvaluescalledlogits,9)andthentwotypes oflinearregressionmodels,asimpleregressionmodelanda“broken-stick”regressionmodelwerefitted tothelogitdataforindividualtestconstructions.Finally,anF-testwascarriedoutforeachconstruction toseewhetherthedatafita“broken-stick”regressionmodelsignificantlybetterthanasimpleregression model.Subsequenttothis,thepresenceofanultimatesuccesseffectwasinvestigatedbyexamining whetherthenativespeakers’successratesfellintotheconfidenceintervalsoftheestimatedmodelsfor thethreeconstructions.

3.5.Results

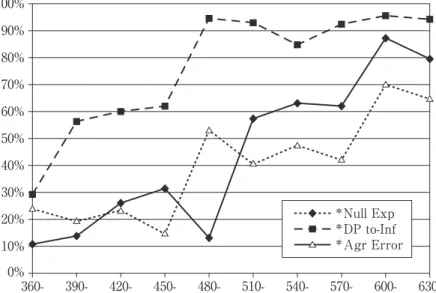

Figure3andTable2offerthepercentagecorrectscoresonthethreetestconstructionsofthe JapaneseleanergroupsandthenativeEnglishgroup.First,letuslookathowwelllearnersperformedon eachconstructiontype.Thehighestscoresonthethreetestconstructionshavebeenachievedbythe sameproficiencyband,600-629.Thescorefor*NullExpis88%,whichisveryclosetothenative speakers’rate,91%.Anative-likeperformanceisalsoobservedinanothertestconstruction,*DPto- Inf.Theband’sscoreis96%,whichisactuallyhigherthanthenativespeakers’score,89%.Therate on*AgrErrorisconsiderablylowerthanthatofthenativegroup.

Asharpriseinsuccessrateseemstobepresentinalltheconstructionsaroundthesameproficiency bands:between480-509and510-539for*NullExp,andbetween450-479and480-509for*DPto-Inf and*AgrError.Thedifferencesinthesuccessratesbetweenthosebandsare45%for*NullExp,33% for*DPto-Infand39%for*AgrErrorrespectively.

Itappearsasiftheconditionsrequiredbythefeature-acquisitionare,notperfectly,butalmostmet. However,ifwetakebothultimatesuccesseffectsanddiscontinuityeffectstogetherintoconsideration, wenoticethatthediscontinuityeffectsobservedinthethreeconstructionshavedifferentcharacteristics. Thesharpriseofthegraphlineof*DPto-Infimmediatelyleadstothenative-equivalentrate,andthis rateismaintainedthroughoutthehigherproficiencylevels.Ontheotherhand,thesharpincreaseinthe

successratesof*NullExpand*AgrErrordoesnotleadtobetterthanchance-levelperformance.The successratesonthosetwoconstructionscontinuetoriseinarathergradualmanner,andeventuallyonly oneofthem,i.e.*NullExp,reachesalevelcomparablewithnativespeakers.

Inordertoidentifyapossiblediscontinuityeffectinthedata,wehavecarriedoutageneralised regressionanalysis.TheresultsaresummarisedinTable3:

Construction *Null Expletive *DP to-Infinitive *Agreement Error

Break Point 600-629 480-509 390-419

F-value 0.2367 1.90 0.6627

The5%significancelevelforF2,6≧5.14

The1%significancelevelforF2,6≧10.98 Table 3. F-values obtained from significance tests of a “broken-stick” regression model against a

simple regression model for the three test constructions, and the positions of break points

Theresultsshowthatnoneofthegraphlinesfitsa“broken-stick”modelsignificantlybetterthana simpleregressionmodel.The5%significancelevelforF2,6isachievedbyanyvaluewhichisgreater thanorequalto5.14.NoneoftheF-valuesofthethreetestconstructionsmeetthiscondition(For*Null Exp,F2,6=0.2367atbreakpoint600-629;For*DPto-Inf,F2,6=1.90atbreakpoint480-509;For*Agr

*Null Exp

*DP to-Inf

*Agr Error

360- 390- 420- 450- 480- 510- 540- 570- 600- 630- 0%

10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

Figure 3. Japanese proficiency groups’ percentage correct scores on each test construction

*Null Expletive *DP to-Infinitive10) *Agreement Error

90.98% 89.33% 86.60%

Table 2. Native speakers’ percentage correct scores on each test construction

Error,F2,6=0.6627atbreakpoint390-419).

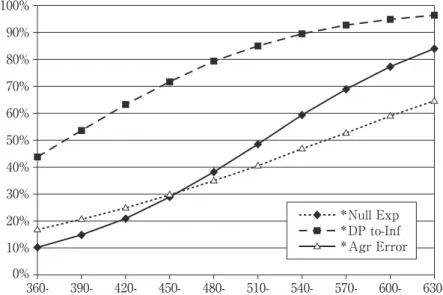

Figure4showstheestimatedsuccessratesofthethreeconstructions,whichhavebeentransformed backtothepercentagemeasurementscalebasedontheresultsofthelogisticregressionanalysis11):

*Null Exp

*DP to-Inf

*Agr Error

360- 390- 420- 450- 480- 510- 540- 570- 600- 630- 0%

10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

Figure 4. Predicted percentage correct scores on the three test constructions after regression modelling

Itisapparentfromtheslopesofthesegraphlinesthatthelearnershavenoticedtheungrammaticalityof

*DPto-Infmuchearlierthanthatoftheotherconstructions.

Usingtheestimatedmodels,thelearners’ultimateachievementisexamined.Theresultsare summarisedinTable4:

Construction Native Rates Lower 95%μ Upper 95%μ

*Null Expletive 2.31 (0.84 2.47)

*DP to-Infinitive 2.12 (2.47 4.41)

*Agreement Error 1.87 (− 0.06 1.32)

Table 4. Native speakers’ correct response rates and the 95% confidence intervals of the correct response rates of the most proficient Japanese group based on the estimated models for the three test constructions(logit)

Itindicatesthatthenativespeakers’scoresfallintotheconfidenceintervalsoftheestimatedsuccess ratesofthemostproficientlearnersonlyin*NullExp,butneitherin*DPto-Inf,norin*AgrError.The learners’estimatedscoreon*DPto-Infisactuallyhigherthanthatofthenativespeakers,whereasthe learners’estimatedscoreon*AgrErrorislowerthanthatofthenativespeakers.Theseresultscanbe interpretedasmeaningthatlearnershavereachedthelevelofnativespeakersintwooutofthethreetest

constructions.

Tosummarisetheresultswithrespecttoafeature-learningeffect,thereisnodiscontinuityeffect observedinthedataofthethreeconstructions,whilsttheultimatesuccesseffectissatisfiedfortwoof thethree.

4.Discussion

Thepatternsrevealedbythegraphlinesofthethreeconstructionsarenotconsistentwiththepattern expectedfromeitherofthefeature-acquisitionmodelsdescribedinprevioussections(see2.2.and2.3.). IfSLAwascarriedoutinthesamewayasL1acquisition,thesuccessratesofallthreeconstructions wouldincreaseatmoreorlessthesametime,andreachthelevelofnativespeakers.If,ontheother hand,SLAwascarriedoutasWakabayashiclaims,thesuccessratesof*NullExpand*DPto-Infwould increasearoundthesametimeandearlierthantherateof*AgrError.Itwouldbecertainlyexpectedby neitherofthemodelsthatonlythesuccessrateof*DPto-Infwouldbegintorisesharplymuchearlier thantheratesoftheotherconstructions.Thusitisnotlikelythatthelearnershaveacquiredtheir linguisticknowledgeoftheirtargetlanguagethroughlearningnewfeatures,atleastinsuchfashionsas thosemodelsclaim.

AssumingthatnonewfeaturesareavailabletoadultL2learners,letusnowconsiderthequestions ofwhatmechanismisinvolvedinSLAandhowitcanaccountforthepatternstheJapaneselearners haveexhibitedinrespondingtotherespectivetestconstructions.Wearguethat“L1transfer”canoffer ananswertothesequestions.Weunderstand“L1transfer”asthephenomenonwhereL2learners associatelexicalitemsormorphophonologicalmaterialsoftheirtargetlanguagewiththefeaturesof theirnativelanguage,asTsimpliandcolleaguesargue.Furtherweclaimthattheassociationormapping processisbasedonsimilarityinmeaningand/orfunctionbetweenthelexicalitemsoftwolanguages

(Kuribara2000;cf.Keller-Cohen1979;Kellerman1977;Jordens&Kellerman1978;Selinker1996; Wode1976,1978,1980).Wealsoclaimthattheprocessisautomatic(Selinker1996),reflectinga propertyofmodularity.Inotherwords,learnersproduceanddecodeasecondlanguage,implementing thealreadyexistingpropertiesintheirlinguisticmodule.Letusseehowthistheoryaccountsforour researchdata,focusingontheperformancebylowproficiencylearners.

Withrespectto*NullExp,allthetestsentencesrequireexpletiveitassubjectinordertobe grammaticallycorrect.Ourdatashowthatthelearnersoverwhelminglyaccept*NullExp.Wesuspect thatthisisduetothefactthatsubjectsneednotbeprojectedinovertsyntaxinJapanese,duetolackof thestrongDfeatureandNominativecasefeatureinT.Therefore,Japanesedoesnotpossesssuchan elementasanexpletiveitorafunctionallysimilarlexicalitem,hencealsolacksastructureinvolvingthe

element.Inaddition,alltheargumentsorθ-markedphrasesnecessaryforprocessesinL1syntaxare present in the test sentences.This has led the low proficiency learners to the acceptance of the ungrammaticalconstruction,*NullExp.

Wesuspectthatthelowproficiencylearners’unsuccessfulperformanceon*NullExpispartly attributabletotheexistenceofatopicphraseinfrontofaverb.Thismighthavedisguisedtheapparent lackofsubjectintheconstruction,whichistoosalientnottonotice.Weclaimthatthelearnershave misanalysedthe[subject[predicate…]]structureofEnglishasthe[topic[predicate…]structureof Japanese.Thisiscausedbythesimilaritybetweenthosetwostructures,describedinsection3.1.Thetest sentencesof*NullExpcontainthe[topic[predicate…]]structure.Usingthewronganalysis,thelower proficiencylearnersendupacceptingtheungrammaticalconstruction(cf.Sasaki1990,Sawasaki 1996).

Acloselookatthedatasupportsthisanalysis,andrevealsaninterestingfact.Threeoutofthefive testsentencescontainatopicalisedPP.Thereare262incorrectresponsesasawhole.Outofthis,58 responseshavebeencategorisedasincorrectalthoughthesentenceshavebeencorrectlyrejected.Thisis becauseonlytheprepositionsinthePPtopicphrasesareunderlinedandbecausethisdoesnotconform tothecriteriasetforthecorrectresponsesfor*NullExp(seeAppendixB).Thisimpliesthatthe learnersevenatthelowproficiencylevelareawarethatinEnglishaclausenormallyhasaphrasebefore averbandthatthisphrasehastobeanounphrase.Whattheydonotknow,however,isthatthenoun phrasehastobeanargument,ifnotanexpletive,inEnglish.Thisconfirmsourclaimthatthelearners havenotacquiredanewfeaturesuchasthe[strongD],whichtriggersthemovementofaDPfrom[Spec, VP]to[Spec,TP].

Theresultson*AgrErrorcanalsobeaccountedforstraightforwardlybyourtheory.Thelow successratesproducedbythelowproficiencylearnersareexplainedagainbytheuseoftheirL1 knowledge,whichlacksmorphemeencodingΦ-featuressuchasNumber.Thisimpliesthatthelearners cannotassociatetheverbin*AgrErrorwiththefeature,butsimplymapthecategoricalfeatureVand thetensefeature[+/−past]ontoit.

TheL1transfertheorybasicallyclaimsthatifthelearners’L1possessesthesamesyntactic propertiesastheirL2,thelearnerswouldexhibithighsuccessrates,correctlyjudgingthegrammaticality ofaparticularstructure.ButhighsuccessratesareexpectedbythetheoryalsointheconditionwhereL1 syntacticknowledgecoincidentallymakesthesamejudgementasL2syntacticknowledgedoes,evenif therelevantsyntacticpropertiesofL1aredifferentfromthoseofL2.Thisiswhatweobservefromthe resultsof*DPto-Inf:

(10)a.To-infinitiveasaclausalsubject

*John[tokillMary]isunthinkable.

b.Mearii-okorosu-koto

Mary-acckill-nomimaliser

(11)a.To-infinitiveasapurposeclause

*Mary[toconcentrateonherwork],Johnkeptquiet.

b.shuuchuushiteshigoto-osuru-tame

concentratework-accdo-nominaliser

(10a) and (11a) are ungrammatical sentences, having an overt DP in front of a non-finite clause. (10b) and (11b) are possible Japanese translations of the underlined parts of (10a) and (11a) respectively, where the infinitive to is understood as a nominaliser. It is unclear, even from L1 syntactic point of view, how those two nominals, JohnandMary,canformasyntactic objectwiththerestoftheclause.

(12)InterlanguageAnalysisof‘JohntokillMaryisimpossible.’ TP

VP T

? John

V, NP

is unthinkable kill Mary

TP to

ThisisreflectedintheJapaneselearners’successfulperformanceevenfromtheearlyperiodoftheL2 acquisitionprocess.

Nonetheless,itmaystillbearguedwhythesuccessrateofthelowproficiencylearnersonthis constructionisnotashighasthatofthenativespeakersifthelearners’nativesyntaxregardsthe structure illicit.This can be explained if we assume, following the‘LexicalTransfer’partof Wakabayashi’smodel,thatthereisapre-functionalstageduringwhichlearnersarestilllookingfor suitablematchesbetweenL2lexicalformsandL1features(cf.Selinker1996).

5.Conclusion

ExaminingJapanesespeakers’acquisitionpatternsofconstructionsinvolvingsubjectsandverbal inflectionsinEnglish,wehaveshownthatlowproficiencylearners’datacanbeplausiblyaccountedfor byaFullTransfermodelratherthanaFeature-Learningaccount.Ithasbeenfoundthatthelearners’ successratesontheconstructionsdonotclusterorrevealthepatternsinthewaysexpectedbyfeature- learning models, the model generally assumed by L1acquisitionandthemodelsuggestedby Wakabayashi(2002a).Incontrast,anautomaticL1feature-mappingtheoryhasbeenabletoofferan explanationforthefactthatthelearnersnoticetheungrammaticalityof*DPto-Infmuchearlierthanthat of*NullExpand*AgrError:theformerstructuretendstoberejectedbecauseitisalsoungrammatical inL1,whilstthelatterstructurestendtobeacceptedbecauseL1doesnotpossessfeaturesandlexical formsequivalenttoanexpletiveoragreementmorphology,andhencethelearnersdonotnoticethe mismatchinfeaturespecificationsbetweensubjectsandverbs.

6.ImplicationsforaTheoryofTransfer:Selinker(1992,1996)

Selinker(1992),referringtoWeinreich(1953),suggestswhathebelievesisabasicSLAlearning strategy,whichseemstoserveasanunderlyingmechanismforthe‘similarity’accountsuggestedby Kellerman(1977)amongothers.Thisiscalledinterlingualidentification.Thefollowingpassage explainstransferusingtheconcept.

Whatlanguagetransferisaboutisthatlearnerstakewhattheyknowfromtheir NL[nativelanguage]andlook,intheTL[targetlanguage]input,forcategories thatmatch.…Thesecognitivemechanismswhichprovideameanstoidentify whichfeaturesoftheTLinput‘resembles’featuresofNL,appeartofunction automatically(Selinker1996,p.102)

Thisstatementcanonlybeunderstoodinmoreconcreteterms,ifwetakeanapproachofthe MinimalistProgramandtheModularTheoryofthemindaswehavesuggestedinthispresentstudy. Thiswayofunderstandingtransferwillprovideuswithanswerstoaseriesofquestionsraisedby Selinker.Featuresaretheunitoflanguagethatinterlingualidentificationisconcernedwith.Theproperty generic to the modular structure of the mind forces the identification process.Transferability is determinedbythesimilarityoflexicalitemsoftwolanguagesintermsoftheirmeaningsandfunctions thatcanbecapturedfromtheinput.Thus,thestructuresthathappenedtobeungrammaticalasaresultof L1mappingaretobecorrectlyrejectedornottobeproduced.Italsoseemstobetruethattransferability isalsoinfluencedbycognitivelysalientaspectsofstructure,suchastheexistenceofanovertnoun

phrasebeforeapredicate.

End Notes

1)TheearlierversionofthispaperwaspresentedatSecondLanguageResearchForum2002,organisedby OISE,theUniversityofToronto.Iwouldliketothankmyaudience,especiallyTaniaIonin,MikiShibata, ShigenoriWakabayashiandLydiaWhitefortheirvaluablecomments.IamalsogratefultoYoichiMiyamoto andShigenoriWakabayashifortheirinsightfulcommentsonthefirstdraftofthispaper.Lastbutnotleast,I wouldliketoacknowledgegratefullythatthisresearchwasfinanciallysupportedbytheKansaiUniversity Grant-in-aidfortheFacultyJointResearchprogramme2002.

2)The term lexicalitem here means a bundle of features which only encode minimum information necessary for the computational system to yield the LF representation and for the phonological component to construct the PF representation. Thus, the information may be a phonological matrix, semantic properties, categorical feature and other idiosyncratic properties that are unpredictable from UG or other properties of the lexical entry.

3)Finite T possesses Nominative case; non-finite T possesses Null case. It should also be noted that within the VP-shell analysis where VPs have a complex structure consisting of an inner VP core and an outer vp shell, v, the head of vp, is a functional category and possesses Accusative case. All the three Cases are regarded as variants of a single feature in Chomsky(2000).

4)Wakabayashi (personal communication) points out that PRO, without phonological features, may not be raised from [Spec, VP] to [Spec, IP] in overt syntax, and that the features such as null case may be checked and erased in covert syntax. We think, however, that if a structure is formed in a bottom-up fashion as Chomsky

(1995) claims, PRO, or more precisely, the categorical feature of PRO needs to be raised to [Spec, IP] in order for the upper part of the syntactic object to be built. It is possible, though, for a feature like null case to be checked covertly, respecting the Principle of Procrastinate.

5)Wakabayashi(personalcommunication)arguesthatitisnotplausibletopredictthatthetwotest constructions,*NullExpand*DPInf,wouldshowasimilaracquisitionpattern,becauseofadifferencein inputrelevanttothoseconstructions.Hesaysthatinordertodetecttheungrammaticalityof*NullExp, learnersneedtoknowthatanullsubjectisnotallowedinfrontofafiniteverb;whereasinordertonoticethe ungrammaticalityof*DPInf,learnersneedtoknowthatapropernounrequiresacomplementizersuchasfor whichservesasacasechecker.Wewouldargue,however,thatcorrectlyrejecting*NullExprequireslearners torealisethatnotnullbutonlyovertsubjectsareallowed,andthatinanexactlyparallelfashion,correctly rejecting*DPInfrequireslearnerstorealisethatnotovertbutonlynullsubjectsareallowed.Therefore,we believethattherearelogicalgroundstoexpectthatthetwotestconstructionswouldshowasimilaracquisition pattern.

6)Wakabayashi(personalcommunication)arguesbasedonhisrecentstudy(Wakabayashi2002b)thatthe errorrateson(9c)wouldbeloweriftherewasnointerveningelement,suchasstill,betweenthesubjectand theverb,suggestingthatlowersuccessrateson(9c)incomparisonwiththoseinotherconstructionsare attributabletoaperformancefactorratherthanthelearners’knowledge.Thisispossible;however,itis unlikelythatthelearners‘apparentlowsuccessrateon(9c)isaresultofasignificantamountofinfluencefrom

aperformancefactor.Thisisbecausethenativespeakersarealsopronetoaperformancefactorandactually knowntomakeagreementerrorsinsuchacondition,butbecauseevenunderthisconditiontheirsuccessrates onthethreeconstructionsin(9)clusterataroundthelevelof90%(seeTable2).

7)Wakabayashi(2002a;personalcommunication)statesthathisSLAmodelpredictsagradualratherthan suddendevelopmentbecauseSLAinvolveslearningindividuallexicalitems.Nonetheless,itcanbearguedthat oncearelevantfeatureisacquired,thelearningprocesswouldbeaccelerated

8)Schwartz&Sprouse(1994)claimthatunlikethecaseofchildL1acquisition,adultL2acquisitionhasthe determinacyproblemwheretheacquisitionprocessisnotdeterministicallydriven.S&Sspeculatethatthe problemiscausedbythefactthatL2learnersstartwithL1parametervaluesandthattheremaynotbeinput whichcanforceretractionfromthepre-fixedparametervaluesortheparametervalueswhicharesetduringthe acquisitionprocess.Onceaparametricpropertyisacquired,i.e.aparameterissetfrom[−]to[+],itisdifficult to‘delearn’it,unlessthereispositiveinputwhichinformsthelearnersthatthesettingisincorrectforthe targetlanguage.AccordingtoS&S,thisisthereasonwhyL2learners’successisusuallyincompleteordoes notreachnativespeakers’leveldespitethatL2acquisitionisguidedbyUGandlearnabilityconsiderationsin thesamewayasL1acquisition.Thelogicseemstoimplythatitwouldbemoredifficultforthenativespeakers ofanL1whichhasmanyparameterssetintothe[+]valuestolearnanL2whichhasfewparameterssetinto the[+]values.Thisisbecausethelearnerswouldhaveto‘delearn’manyparametricproperties.Incontrast,it wouldbeeasierforthenativespeakersofanL1whichhasfewparameterssetintothe[+]valuestolearnanL2 whichhasmanyparameterssetintothe[+]values,becausetheprocessof‘delearning’wouldnotbe involved.Thismaysuggestthatinthelattercase,L2acquisitionwillproceedjustlikeL1acquisition.The latterwouldbewhatisexpectedintheirTurkishsubject’sacquisitionofGerman.However,hisacquisition processdidnotfollowtherouteofnativeGermanacquisition.ThishasbeenshownbyS&S’sanalysisofthe dataindicatingthatheseemedtohaveacquired(atleastatonepointofthedevelopmentalprocess)some parametricpropertieswhichdonotexistinthetargetgrammar,suchasleft-adjunctiontoCPandnominative casecheckedunderincorporation.S&S(1994,p.350)attempttoexplainthecauseofthisdivergencefromthe nativerouteinthefollowingway:

[F]romacomputationalperspective,thenumberofpossibilitiesthatwouldneedto becomputedinordertomovestraightfromtheL1grammarto‘the’German grammarwouldseemtobeenormous;inthissense,smalleradaptationsmadeto theexistingsystemcanbeseenasmorehighlyvalued,forthepreciseeffectsofsmall and/orlocalized,incrementalchangescanbemoreeasilycomputedwithrespectto theincomingPLD[primarylinguisticdata].

Ifthisisthecase,thenthecauseofthedeterminacyproblem,i.e.theproblemforL2acquisition,ultimately liesinthecomputationalburdenwhichrequireslocalisedoperationsfortheaccommodationoftheinternal syntacticrepresentationtothetargetinput.WiththeassumptionthatL2acquisitionisledbythesame mechanismasL1acquisition,thereisnonecessaryreasonthatL2learnershavetostartoffwithtransferring theirL1parametricoptionsinthefirstplace.ItisunclearwhyonlyL2learnerswouldhavetoexperience computational restriction and go through a series of unnecessarily complicated adjustments of L1 representation,iftheywereguidedbythesamemechanismasnativeacquirers.ThiscastsdoubtonS&Sユ s modelitselfandtheirclaimthatadultL2learners ユachievingnativespeakers ユlevelisnotanecessary conditionforparameter-setting.

9)Thelogistictransformationwascarriedoutaspartofaprocedureforlogisticregressionanalysis,usingthe statisticalpackage,SAS.TheformulaforthetransformationinputtedinaSASprogramis:Log(p/(1−p)) wherep=proportion.

10)Itshouldbenotedthattwosentencesoutofthefive*DPInfconstructioncontainedgerundivalclauses. About30%ofthetime,theywereoftenacceptedbythenativespeakergroup,andtheoverallsuccessrateon theconstructionwas76.2%.Wethereforedecidedtore-calculatetheresultsoftheconstructionforbothsubject groupsbyincludingonlyto-infinitives.Wethenre-labelledtheconstructionas*DPto-Inf.

11)Logisticvaluesobtainedfromthelogisticregressionweretransformedtopercentages.Theformulawhich changeslogitstopercentagesisp=1/(1+e-z),wherep=proportion,andz=logit.Thecalculationwasdone usingExcel.

References

Chomsky,N.(1995).TheMinimalistProgram.Cambridge,Massachusetts:TheMITPress.

Chomsky,N.(2000).MinimalistInquiries:TheFramework.InM.Martin,D.Michaels&J.Uriagereka(Eds.), StepbyStep:EssaysonMinimalistSyntaxinHonorofHowardLasnik(pp.89-155).Cambridge, Massachusetts:TheMITPress.

Chomsky,N.,&Lasnik,H.(1995).TheTheoryofPrinciplesandparameters,MinimalistProgram(pp. 13-127).Cambridge,Massachusetts:MITPress.

Eubank,L.(1993/4).OnthetransferofparametricvaluesinL2development.LanguageAcquisition,3(3), 183-208.

Eubank,L.(1994).OptionalityandtheinitialstateinL2development.InT.Hoekstra&B.D.Schwartz(Eds.), LanguageAcquisitionStudiesinGenerativeGrammar(pp.369-388).Amsterdam:JohnBenjamins PublishingCompany.

Eubank,L.(1996).NegationinearlyGerman-Englishinterlanguage:MorevaluelessfeaturesintheL2initial state.SecondLanguageResearch,12(1),73-106.

Fodor,J.A.(1983).ModularityofMind.Cambridge,Massachusetts:TheMITPress.

Fukui,N.(1995).Theprinciples-and-parametersapproach:AcomparativesyntaxofEnglishandJapanese.InM. Shibatani&T.Bynon(Eds.),ApproachestoLanguageTypology(pp.327-372).NewYork:Oxford UniversityPress.

Franceschina,F.(2001).Morphologicalorsyntacticdeficitsinnear-nativespkeakers?Anassessmentofsome currentproposals.SecondLanguageResearch,17(3),213-247.

Fukui,N.(1995).TheoryofProjectioninSyntax.Stanford,California/Tokyo:CSLIPublications,Center fortheStudyofLanguageandInformation,StanfordUniversity/KurosioPublishers.

Gerken,L.A.&McIntosh,B.J.(1993).InterplayofFunctionMorphemesandProsodyinEarlyLanguage. DevelopmentalPsychology,29,448-457.

Hakansson,G.,Pienemann,M.,&Sayehli,S.(2002).Transferandtypologicalproximityinthecontextof secondlanguageprocessing.SecondLanguageResearch,18(3),250-273.

Hoekstra,T.,&Hyams,N.(1995).Thesyntaxandinterpretationofdroppedcategoriesinchildlanguage:A unifiedaccount,ProceedingsoftheWestCoastConferenceonFormalLinguistics,Vol.XIV(pp. 123-136).Stanford,California:CSLI,StanfordUniveristy.

Hoekstra,T.,Hyams,N.,&Becker,M.(1999).Theroleofthespecifierandfinitenessinearlygrammar.InD.

Adger,S.Pintzuk,B.Plunkett,&G.Tsoulas(Eds.),Specifiers:MinimalistApproaches(pp.251-270): OxfordUniversityPress.Hoji,H.(1985).LogicalFormConstraintsandConfigurationalStructures inJapanese,UniversityofWashington.

Ishii,Y.(1991).OperatorsandEmptyCategoriesinJapanese.Ph.D.Thesis,TheUniversityof Connecticut.

Jordens,P.,&Kellerman,E.(1978).Investigationsintothe‘transferstrategy’insecondlanguagelearning.In J.-G.Savard&L.Laforge(Eds.),Proceedingsofthe5thCongressofl’AssoicationInternationalede LinguistiqueAppliquee,Montreal(pp.195-215).Quebec:LesPressesdel’UniversiteLaval.

Keller-Cohen,D.(1979).Systematicityandvariationinthenon-nativechild’sacquisitionofconversational skills.LanguageLearning,29(1),27-44.

Kellerman,E.(1977).Towardsacharacterizationofthestrategiesoftransferinsecondlanguagelearning. InterlanguageStudiesBulletin,2,58-145.

Kuribara,C.(1999a).ResettabilityofasyntacticparameterinSLA:Non-acquisitionofcategoryCinEnglish byadultJapanesespeakers.InC.Perdue(Ed.),FromWordtoStructure,Aile(AcquisitionetInterac- tionenLangueEtrangere):Proceedingsof8thEUROSLA(EuropeanSecondLanguageAssocia- tion)Conference,Vol.2(pp.119-132).Paris:BritishInstituteinParis.

Kuribara,C.(1999b).Resettabilityofasyntacticparameter:AcquisitionofcategoryDinEnglishbyadultJapa- nesespeakers.InP.Robinson(Ed.),RepresentationandProcess:Proceedingsofthe3rdPacificSec- ondLanguageResearchForum,Vol.1(pp.13-22).Tokyo:AoyamaGakuinUniveristy.

Kuribara,C.(2000).ResettabilityofUGParametersinSLA:AcquisitionofFunctionalCategoriesby AdultJapaneseLearnersofEnglish.Ph.D.Thesis,TheUniversityofReading.

Lardiere,D.(1998).Caseandtenseinthe‘fossilized’steadystate.SecondLanguageResearch,14(1), 1-26.

Liceras,J.M.,&Diaz,L.(1998).Onthenatureoftherelationshipbetweenmorphologyandsyntax:Inflectional typology,f-featuresandnull/overtpronounsinSpanishinterlanguage.InM.-L.Beck(Ed.),Morphology andItsInterfacesinSecondLanguageKnowledge(pp.307-338).Amsterdam:JohnBenjaminsPub- lishhingCompany.

Meisel,J.M.(1995).Parametersinacquisition.InP.Fletcher&B.MacWhinney(Eds.),TheHandbookof ChildLanguage(pp.10-35).Oxford:Blackwell.

Prevost,P.,&White,L.(2000).Missingsurfaceinflectionorimpairmentinsecondlanguageacquisition?Evi- dencefromtenseandagreement.SecondLanguageResearch,16(2),103-133.

Radford,A.(1997).SyntacticTheoryandtheStructureofEnglish:AMinimalistApproach.Cam- bridge:CambridgeUniversityPress.

Saito,M.(1985).SomeAsymmetriesinJapaneseandtheirTheoreticalImplications.Ph.D.Thesis, MIT.

Sasaki,M.(1990).TopicprominenceinJapaneseEFLstudents’existentialconstructions.LanguageLearn- ing,40(3),337-368.

Sawasaki,K.(1996).Topic-prominenceasanobstacleforJapaneseEFLlearners.TheORTESOLJournal, 17,41-54.

Schwartz,B.D.,&Sprouse,R.A.(1994).Wordorderandnominativecaseinnon-nativelanguageacquisition:A longitudinalstudyof(L1Turkish)Germaninterlanguage.InT.Hoekstra&B.D.Schwartz(Eds.),Lan-